Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Psychiatry

On-line version ISSN 2078-6786

Print version ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.21 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajp.580

CASE REPORT

Genital self-mutilation in a non-psychotic male to get rid of excessive sexual drive: A case report

A TripathiI; B TekkalakiII; A AgarwalIII

IMD; Department of Psychiatry, King George Medical University, Lucknow, India

IIMD; Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Belagavi, India

IIIMD; Department of Psychiatry, Integral Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Lucknow, India

ABSTRACT

Genital self-mutilation (GSM) is a rare phenomenon. In the majority of cases, GSM is secondary to psychotic illness. Among the non-psychotics, the motives behind GSM are varied. We report a rare case in which a non-psychotic, non-paraphilic patient suffering from excessive sexual drive carried out GSM to curb hypersexuality. Aetiological factors behind GSM are discussed. This case report emphasises that excessive sexual drive may lead to distress and GSM. Effective management of excessive sexual drive and active inquiry into any intentions of GSM in such patients may be helpful in preventing GSM.

Genital self-mutilation (GSM) is a rare phenomenon. Most of the reported cases of GSM are in psychotic patients; there are very few case reports of GSM in non-psychotic patients.[1,2] Among non-psychotic patients, the reported reasons for GSM vary, ranging from normal cultural beliefs to paraphilias to substance intoxication.[1,3,4] We present a rare case of GSM in which a non-psychotic, non-paraphilic patient attempted GSM in order to get rid of his excessive sexual drive.

Case report

A 25-year-old male, having completed his high school education and currently unemployed, presented with the complaint of excessive sexual desire since adolescence. The patient's history revealed an excessive sexual desire that began during the early adolescent period and led to an excessive preoccupation with thoughts of having sexual intercourse, frequent sexual arousals in inappropriate situations (such as classrooms), frequent indulgence in erotic literature and masturbation multiple times a day. The symptoms increased gradually both in frequency and severity. He also started visiting prostitutes at the age of 18 years.

The patient reported that he felt these sexual desires, thoughts and arousals to be excessive and distressing. He initially attempted to overcome the desires by chanting prayers, taking frequent cold baths, etc. but was unsuccessful. The patient experienced increased tension when he tried resisting the sexual thoughts or actions, and his tension was relieved by indulging in the sexual acts. However, he enjoyed the sexual acts when involved in them.

The patient's scholastic performance gradually deteriorated. He failed in Grade 11 exams and gave up further studies. He gradually began neglecting his areas of interest such as art, cricket and movies. He spent most of his time watching pornographic movies or indulging in sexual activity with prostitutes. In order to afford the prostitutes, the patient ended up stealing money from home.

In the hope of putting an end to the patient's problems, his parents arrange for him to marry. After marriage, he would indulge in sexual activity with his wife 8 - 10 times a day. Often, he had sex forcefully, against his wife's will. Within 1 year their marriage ended owing to his hypersexuality. The patient attempted to continue his job, but in vain.

The patient reported that he sought help from several psychiatrists. The available treatment records suggested that he was given fluoxetine up to 60 mg/day for 6 months and sertraline up to 200 mg/day for 8 months, without any significant benefit. He lost hope in the treatment and as a last measure, to put an end to his misery, he attempted to cut his sexual organ with a shaving blade. The act was incidentally observed by his father, and he was immediately brought to the emergency unit, where the incision wounds on the penis were surgically managed. Subsequently, he was referred to the sex clinic of our department and he consented to hospitalisation.

There was no significant past or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior history of any substance abuse. Developmental history was not contributory. There was no history of any childhood abuse. The patient had good premorbid adjustment. Mental status examination revealed normal cognitive functions, sadness of mood, worry about the excessive sexual desire and its consequences, occasional hopelessness and complete insight. No delusions or hallucinations were present.

Screening for sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, HBsAg and syphilis were negative. Hormonal assay showed normal androgen levels and a computed tomography scan of the brain was normal. A diagnosis of excessive sexual drive (ICD-10 F52.7) was made. Informed consent was taken and the patient was initiated on depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection 150 mg intramuscular, every fortnight. The patient's symptoms improved gradually over the next 2 months and hypersexual behaviour inventory (HBI-19) scores decreased to >50% from baseline. The patient and his parents were psychoeducated and relaxation techniques were taught. Alternative sources of recreational pleasure, such as sketching, music and indoor games, were utilised successfully. Rehabilitation was planned and the patient was discharged after 2 months. He was followed up for a period of 6 months and his symptoms were found to have improved further. The frequency of sexual thoughts and masturbation were reduced to 1 - 2 times a day. He stopped visiting prostitutes and resumed his job.

Discussion

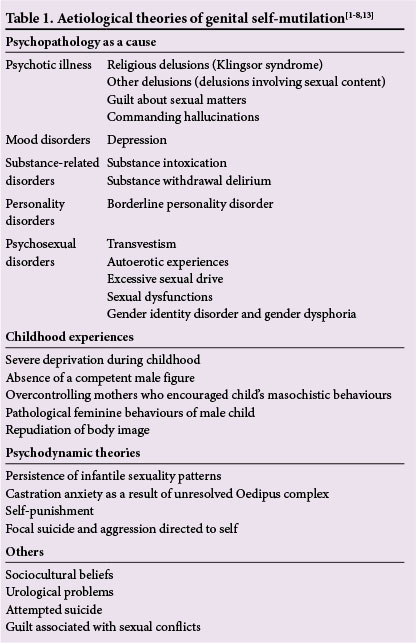

GSM is a rare but serious phenomenon. The available literature indicates that the majority of GSM is carried out by psychotic patients, secondary to delusions, commanding hallucinations or due to sexual guilt.[1] In Klingsor syndrome, GSM is specifically due to underlying religious delusions.[5] Among non-psychotic patients, GSM may also occur owing to sociocultural influences.[1] GSM is also reported in cases of borderline personality disorders, sexual dysfunction, urogenital problems, gender dysphoria and as attempted suicide.[3,5,6] Among paraphilics, GSM may be carried out as an attempt to change sex, e.g. by transsexuals, or as an autoerotic method.[5,7] Psychiatric syndromes associated with GSM are enumerated in Table 1.

This patient had no symptoms suggestive of psychosis. He did not have any personality disorder and he denied any gender dysphoria or sexual perversions. The motive behind the act was not suicidal, as the patient clearly reported that he attempted GSM as an effort to curb hypersexuality. Reported cases of GSM to curb hypersexuality are extremely rare. Kalin[8] reported a case in which the patient attempted GSM and denervation of his adrenals to stop hormonal production and hence, hypersexuality.

The phenomenology in the index patient is different from that of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). In OCD, patients have a fear of committing sexual offences or incest and not sexual fantasy. Sexual obsessions do not lead to arousal and sexual acts. The fact that two trials of high doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) did not show any benefit may also negate the diagnosis of OCD.

The role of medroxyprogesterone in treating hypersexual behaviour is demonstrated in various small studies and many case reports. In a comparative study, Meyer et al.[9]demonstrated that patients on medroxyprogesterone achieved better control over hypersexual behaviour and had a lower rate of re-offence compared with controls. Gagne[10] reported significant improvement in hypersexual symptoms in 40/48 male sex offenders who were treated with medroxyprogesterone acetate and milieu therapy for 12 months. In a case series by Cross et al.,[11] 10 dementia patients with inappropriate hypersexuality showed significant improvement with an oral dose of 100 - 400 mg/day. However, McConaghy et al.[12] reported no significant difference in terms of reduction of hypersexual behaviour between three groups of patients: medroxyprogesterone alone (n=10), imaginal desensitisation alone (n=10) and combined treatment (n=10). Even though there is a need for well-designed large trials in this area, it can be concluded that the available evidence encourages the use of medroxyprogesterone acetate. The failure of SSRIs and occasional ideas of repeating GSM in this patient prompted this option. Considering the impairment in the patient's life, aggressive management was needed.

Common side-effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate are weight gain, malaise, migraine, leg cramps, blood pressure elevation, gastrointestinal disturbances, gallstones and diabetes mellitus.[9] The patient was regularly monitored for these and none were reported.

Conclusion

This case report emphasises that excessive sexual drive may lead to distress and GSM. The therapist should actively look for any intentions of GSM in patients with excessive sexual drive in order to prevent any serious damage.

References

1. Greilsheimer H, Groves JE. Male genital self-mutilation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36(4):441-446. [ Links ]

2. Aboseif S, Gomez R, McAnich JW. Genital self-mutilation. J Urol 1993;150(4):1143-1146. [ Links ]

3. Mishra B, Kar N. Genital self-amputation for urinary symptoms relief or suicide. Indian J Psychiatry 2001;43(4):342-344. [ Links ]

4. Martin T, Gattaz WF. Psychiatric aspects of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology 1991;24(3):170-178. [ Links ]

5. Bhargava SC, Sethi S, Vohra AK. Klingsor syndrome: A case report. Indian J Psychiatry 2001;43(4): 349-350. [ Links ]

6. Feldman MD. More on female genital self-mutilation. Psychosomatics 1988;29(1):141. [ Links ]

7. Wan SP, Soderdahl DW, Blight EM Jr. Non-psychotic genital self-mutilation. Urology 1985;26(3):286-287. [ Links ]

8. Kalin NH. Genital and abdominal self-surgery: A case report. JAMA 1979;241(20):2188-2189. [ Links ]

9. Meyer WJ, Cole C, Emory E. Depo provera treatment for sex offending behaviour: An evaluation of outcome. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1992;20(3):249-259. [ Links ]

10. Gagne P. Treatment of sex offenders with medroxyprogesterone acetate. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138(5):644-646. [ Links ]

11. Cross BS, DeYoung GR, Furmaga KM. High dose oral medroxyprogesterone for inappropriate hypersexuality in elderly men with dementia: A case series. Ann Pharmacother 2013;41(1):e1. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1345/aph.1R533] [ Links ]

12. McConaghy N, Blaszczynski A, Kidson W. Treatment of sex offenders with imaginal desensitization and/or medroxyprogesterone acetate. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988;77(2):199-206. [ Links ]

13. Ozan E, Deveci E, Oral M, Yazici E, Kirpinar I. Male genital self-mutilation as a psychotic solution. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2010;47(4):297-303. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

B Tekkalaki (tbheemsain@gmail.com)