Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Psychiatry

On-line version ISSN 2078-6786

Print version ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.21 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajp.641

ARTICLE

Medical students' experience and perceptions of their final rotation in psychiatry

R du PreezI; A-M BerghII; J GrimbeekIII; M van der LindeIV

IMB ChB, MMed (Psych); Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIBA (Hons), BEd (Hons), PhD; Medical Research Council Unit for Maternal and Infant Health Care Strategies, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIIBSc (Hons), MSc; Department of Statistics, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IVBSc (Hons), MSc, PhD; BSc (Hons), MSc; Department of Statistics, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Evaluation of specific courses, rotations or attachments in medical education is common practice.

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate medical students' perceptions of their final psychiatry rotation of 7 weeks.

METHODS: A questionnaire was developed for medical students to give feedback on their psychiatry rotation at Weskoppies Hospital in Tshwane, South Africa. Four scores were developed: (i) a clinical exposure score for psychiatric conditions encountered during the rotation; (ii) an ethics exposure score comprising confidentiality and informed consent; (iii) an admissions exposure score for different admission options; and (iv) a perception score related to students' experience of the rotation. The evaluation took place over a period of 4 years, between 2006 and 2009.

RESULTS: Over the study period, 87% of 708 students completed the questionnaire. The higher number of female respondents (63%) was in accordance with the general student profile. The four resulting scores were: clinical exposure 67%; ethics exposure 78%; admissions exposure 86%; and perceptions 75%. The main strengths of the rotation were identified as the positive learning environment, exposure to patients, discussions and ward conferences, and approaches followed.

CONCLUSIONS: The conceptualisation of the tool to elicit specific scores was useful for presenting the findings. The student feedback provided valuable information for the psychiatry curriculum planners and teachers, and led to further adaptations to the structure of the rotations and the learning opportunities provided.

Primary care physicians in South Africa (SA) are mental healthcare users' first point of contact with the health system, and are in most instances responsible for their follow-up. It is therefore important that medical students are exposed to patients with mental disorders and to basic interviewing skills, and that they acquire the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage mental healthcare users. Psychiatry started to feature more prominently in the reformed 6-year undergraduate medical curriculum of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Pretoria (UP) in 2001. This was an important development because of a high lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders[1] and the shortage of access to specialist psychiatric care in SA.[2-3] Medical students are introduced to basic principles of psychiatry over a couple of years, culminating in an academic course with a practical rotation at the beginning of their 5th year. The focus is on the role of the generalist in identifying and managing patients with psychiatric conditions. During the last 18 months of their studies, medical students rotate at Weskoppies Hospital, a specialist psychiatric hospital in the city of Tshwane, for a 7-week clinical attachment. At the time of the study, each student was allocated to one of the 5 week-day adult admission groups, where they participated in ward rounds, outpatient clinics and admissions. Students also spent 1 week at the child and adolescent unit. Throughout the programme, there were morning discussions with compulsory preparation and active participation required, case-study conferences and discussions led by consultants, and sessions devoted to interpersonal and microcommunication skills. About one-third of students did this rotation in the 2nd half of their 5th year, and the remaining two-thirds did it in their 6th and final year.

It is a priority of the UP Department of Psychiatry to continuously improve this rotation, as is the case elsewhere in the world.[4-7] Students have provided anonymous feedback at the end of each rotation by means of a self-administered, paper-based evaluation questionnaire since 2001. The main objective of the study, therefore, was to assess the learning opportunities and the quality of learning experienced by students. This activity was also undertaken in line with quality assurance requirements that are increasingly required as part of accreditation processes.[8,9] Most other reported surveys among psychiatry students relate to final-year students' attitudes to psychiatry or psychiatric illness, or to psychiatry as a career choice.[10-17] One study conducted among 85 preregistration house officers in Norway had more similar objectives to those of our study, namely getting a sense of the learning benefits and learning environment of a psychiatry rotation.[18]

This article reports on the findings of undergraduate medical students' evaluation of the final psychiatry rotation at the University of Pretoria over a period of 4 years, and how the findings informed further adaptations to the structure of the programme and opportunities provided to students during the rotation.

Method

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria (protocol 274/2003). Students completed the developed evaluation tool voluntarily and anonymously.

Development of the evaluation tool

The student evaluations were developed in three phases. A pilot study was conducted in 2002 and 2003. The first version of the feedback instrument was used in 2004 and 2005, and was further adjusted in 2006 to expand on students' exposure to different psychiatric diagnoses as required by the Health Professionals Council of SA (HPCSA),[19] and on mental heathcare users' rights in terms of the Mental Health Care Act No. 17 of 2002 (MHCA).[20] The revised tool was used for evaluating student experiences of all psychiatry rotations between 2006 and 2009, with the exception of one rotation in 2007, and is still being used.

Structure of the questionnaire

The final questionnaire for students comprised three sections:

1. Closed questions (Yes/No/Don't know) on exposure to patients with the most prevalent psychiatric conditions

2. Closed questions (Yes/No/Don't know) on exposure to specific activities taking place in a psychiatric institution, namely the respectful treatment of psychiatric patients (ethical issues) and admissions

3. Likert scales (1 - 5) related to perceptions of the psychiatry rotation in terms of usefulness, effectiveness and adequacy, with 5 representing 'Strongly agree' and 1 representing 'Strongly disagree.

The questionnaire ended with three open-ended items probing the strengths and weaknesses of the rotation and recommendations for improvement.

Validity of the instrument

According to Zabaleta,[7] student feedback collected towards the end of a term seems to be an almost universally accepted method of gathering information on teaching. The purpose of obtaining feedback includes evaluation of teaching methods used and/or the effectiveness of a course.[6] Zabaleta,[7] however, argues that student ratings are indicators of consumer satisfaction rather than teaching effectiveness or student learning. Krantz-Girod et al.,[21]however, found that 'medical students can maintain a high discrimination capacity in evaluating the teaching and the teachers'.

Our instrument could be considered as a measurement of course (rotation) effectiveness, with a small component of student satisfaction. The primary objective of the included items was not to evaluate the teaching of psychiatry or the teachers[6] with the purpose of developing the teachers,[9] nor were unfamiliar abstract constructs[8] used for the evaluation. Items mcovering the requirements set by the HPCSA and MHCA contributed to content validity, through the use of official documents as a proxy for expert opinion. The chance of students having different understandings of the intended meaning of items, a problem often associated with student evaluations of courses in general,[8] was therefore minimised. The nature of the items also excluded to a large extent the possibility of 'filtering' judgements to protect individual teachers,[8] or the fear of personal consequences or victimisation. As all blocks and modules are formally evaluated in the course of their medical studies, students were familiar with this kind of evaluation and were therefore likely to give an honest response. It therefore appears as if the questionnaire was to a large extent able to 'gather useful and accurate information for the intended purpose.'[22]

Data analysis

Frequencies and means of individual items were calculated. In order to get a better overview of the student responses, four different scores were created as an indication of different types of exposure and experience:

- Clinical exposure score: different psychiatric conditions and diagnoses

- Ethics exposure score: confidentiality and informed consent

- Admissions exposure score: different types of admissions (voluntary, assisted, involuntary)

- Perception score: students' perceptions of the adequacy, effectiveness and usefulness of the activities in the psychiatry rotations (a type of 'satisfaction' score)

The first three scores were mere counts of different kinds of exposure; the percentage of 'Yes' responses constituted the score. For the perception score, a mean was calculated on a scale of 1 - 5 per item, which was then converted to a percentage.

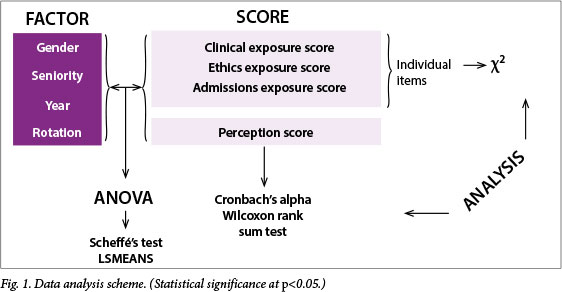

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to compare gender, seniority (5th or 6th year of study), rotation number, actual year (2006 - 2009) and interaction between rotation and actual year by using the perception and three exposure scores. The levels of significant factors were further compared by use of the post-hoc multiple comparison test of Scheffé as well as the least-squares means (LSMEANS) procedure. A χ2 test was used to determine the relationships between factors and individual items comprising the first three scores, whereas items belonging to the perception score were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The items in the perception score were also tested for internal consistency and the result was an acceptable Cronbach's alpha score of 0.81. Open-ended comments were analysed qualitatively to identify important categories. The quantitative methods of analysis are summarised in Fig. 1.

Results

Of the 708 students for the total period, 617 responded. This translates to a response rate of 87%, ranging between 75 and 93% for individual years. The response rate per rotation for the completion of the questionnaires ranged between 40 and 100%. The questionnaire was completed by 391 females (63%) and 210 males (34%), with 16 (3%) of unknown gender. (Female student enrolments for medical studies increased from 55 to 66% during the study period.) Fifth-year medical students comprised 162 (26%) of the total, and 6th years 448 (73%), with the status of seven students unknown (1%).

Clinical exposure to psychiatric conditions

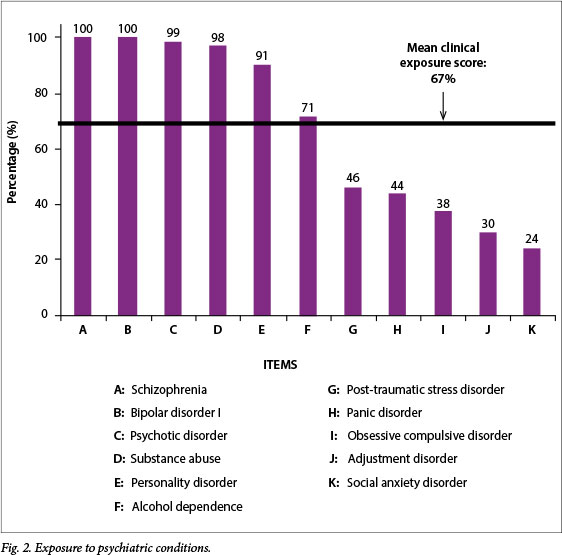

The mean total score for exposure to psychiatric conditions was 67%. During their rotation, more than 95% of respondents had been exposed to bipolar disorder type I, schizophrenia, personality disorder, psychotic disorders and substance abuse (Fig. 2). Slightly more than 70% of students had been exposed to alcohol dependence. For other psychiatric conditions, i.e. social anxiety, adjustment, obsessive compulsive, panic and post-traumatic stress disorders, less than half of respondents had had any exposure (range 24 - 46%). When the different years were compared, there were slight fluctuations in the exposures for all the conditions.

Activities in a psychiatric institution

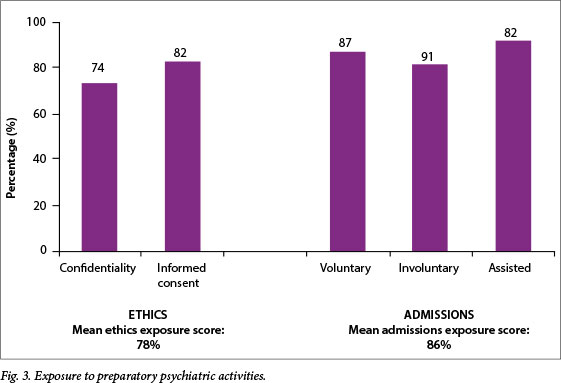

An overview of the exposure of students to activities taking place in a psychiatric institution (respectful treatment and admissions) is given in Fig. 3. The mean ethics exposure score was 78%, with a total of 74% for confidentiality and 82% for informed consent. The mean admissions exposure score was 86%, with 82% for assisted admission, 87% for voluntary admission and 91% involuntary admission.

Perceptions about the rotation

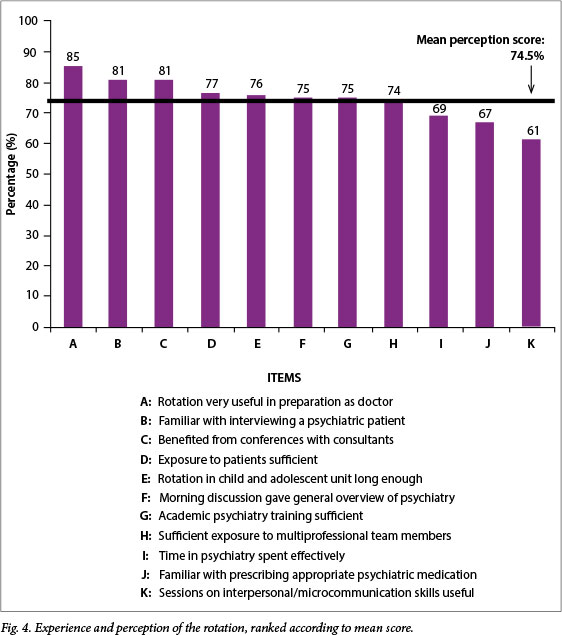

The individual items that comprised the perception score are listed in Fig. 4, in descending order of scores. There did not appear to be a particular trend, apart from the fact that the four highest-scoring items related to students' direct preparation as medical practitioners. One of the important skills, interviewing techniques, scored second highest at 81%. Conversely, respondents felt much less confident about their skills related to prescribing medication (67%). Only 3 of the 11 items had a rating of <70%.

Comparisons

Gender

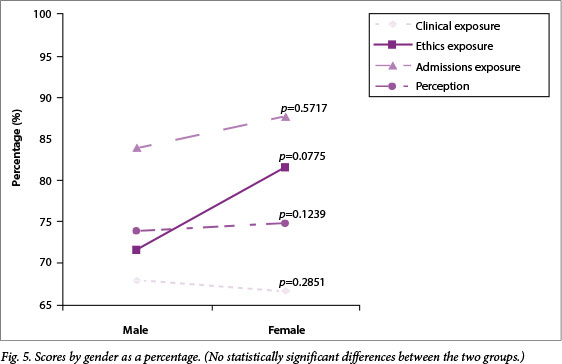

Fig. 5 summarises the aggregated scores for male and female respondents for the four scales that were created. None of these scores demonstrated a significant difference between the two groups. Females did, however, report a significantly higher percentage for both the items on the ethics exposure score, which were confidentiality (p=0.0062) and informed consent (p=0.0058). Regarding differences in exposure on individual items contributing to the clinical exposure score, significantly higher exposures to post-traumatic stress disorder (p=0.0371), adjustment disorders (p=0.0206) and substance abuse (p=0.0187) were observed for female students. In terms of individual items contributing to the perception score, females rated their familiarity with psychiatric interviewing significantly higher than males did (p=0.0001), as well as their satisfaction with the length of time spent in the child and adolescent unit (p=0.0110).

Seniority

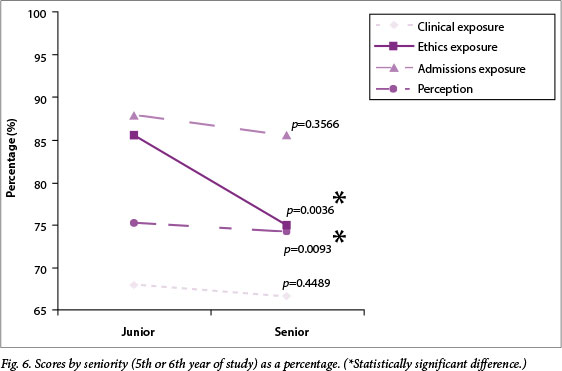

With regard to differences in scores between junior (5th-year) and senior (6th-year) students, there was a significantly higher rating by juniors than seniors on two of the four scores, namely the ethics exposure (p=0.0036) and the perception (p=0.0093) scores (Fig. 6). For both the ethics score items, confidentiality and informed consent, the juniors' responses were significantly higher (p=0.0268 and p=0.0002, respectively). Junior students also had a significantly more positive perception about the sufficiency of their academic training in the psychiatry rotation (p=0.0014) and their familiarity with prescribing psychiatric medication (p=0.0431). With regard to clinical exposure, significantly more juniors reported having had exposure to patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (p=0.0408) than seniors, and significantly more senior students reported exposure to social anxiety disorder (p=0.0356) than juniors.

Years

Two of the four scores demonstrated a significant difference between the different years from 2006 to 2009. The clinical exposure score (p=0.0065) ranged between 64 and 69%. The greatest variation occurred in the ethics exposure score (p<0.0001), initially at 61% in 2006, with a substantial increase to 76% in 2007, ending with over 87% in 2008 and 2009. The admissions exposure score remained stable in a narrow range between 86 and 87%, with no difference between the years (p=0.8541). The perception score of between 73 and 76% showed a tendency to differ, although not significantly so (p=0.0584).

Some individual items had significant relationships with the year in which the evaluation tool was administered. With regard to clinical exposure, alcohol dependence exposure varied between 63 and 89% (p<0.0001). For post-traumatic stress disorder, there was a significant upward trend, with student exposure increasing from 37% in 2006 to 60% in 2009 (p<0.0001). For both items comprising the ethics exposure score, confidentiality and informed consent, the relationships were significant (p<0.0001) in a comparison of different years. Items contributing towards the perception score, for which a significant difference between years was observed, were the usefulness of sessions on microcommunication skills (p=0.0021) and sufficiency of exposure to the multidisciplinary team (p=0.0093).

Rotations

In relation to the rotations taking place at different times of the year, a significant difference was only observed with regard to the perception score (p=0.0107). Both confidentiality and informed consent showed significant relationships with rotations (p=0.0019 and p=0.0052, respectively). The last rotation of each year scored the highest for the ethics exposure score, although this was not statistically significant. For two items contributing to the clinical exposure score, there was a significant relation with rotations, namely alcohol dependence (61 - 81%; p=0.0079) and personality disorder (86 - 97%; p=0.0207). Among the items contributing to the perception score, there were significant differences between different rotations with regard to views on the effectiveness of the time spent in the Department of Psychiatry (p=0.0031), familiarity with prescribing of psychiatric medicine (p=0.0413), morning discussions that give a general overview of psychiatry (p=0.0146), and the usefulness of sessions on microcommunication skills (p=0.0435).

A comparison of the interaction between different years and different rotations, using the four scores, yielded significant differences only for the clinical exposure score (p=0.0003). On closer investigation, no specific trend could be detected with regard to differences between specific years and specific rotations.

Themes from qualitative comments

Finally, themes emerging from the open-ended responses were categorised in terms of strengths and shortcomings of the rotation. The overwhelming positive focus was what could perhaps be called the students' learning environment, which encompasses the friendly and supportive staff (consultants, registrars, nurses) and a relaxed, student-friendly climate that even accommodates students in the tearoom. This is how a few students expressed themselves on this theme:

'For a change, all staff members from the sister to a professor were very approachable, down to earth. They love what they do, which is caring for human beings - patients.'

'Enjoyed the block, was treated well by members of the team. This makes a large difference in my last days as a student.'

'One of the few rotations where you have the privilege to work closely with consultants.'

The other strong positive theme related to the interaction with and treatment of patients, and included more general comments on exposure to patients and psychiatric diagnosis, participation in treatment of patients and the time spent with patients.

'A large proportion of patients I will see at primary care level will have psychiatric conditions. I have learned skills at Weskoppies Hospital that will stand me in good stead when I work with these patients.'

The shortcomings identified with regard to patient exposure comprised a fragmented list of factors that students perceived as representing insufficient exposure to a certain condition or activity that sometimes related to a specific rotation where there had been a problem. Some examples are the cancellation of electroconvulsive treatment or not enough exposure to emergency treatment, somatoform disorders or psychotherapy. A few students also complained about the lack of variation in patients, having too many chronic ward rounds, insufficient exposure to the conditions that they would see as general practitioners, and a lack of confidence in prescribing skills.

'Narrow exposure, most patients either with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder due to general medical conditions or substances.'

'Weskoppies Hospital has a very selected patient population, not really reflecting the patients seen at casualty or clinics.'

One of the recommendations made by a number of students for improving the rotations was increasing lectures for a variety of activity areas such as the morning discussions, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and micro-communication and interpersonal skills.

'Not enough information about medication. Maybe one lecture on pharmacotherapy by a consultant would have helped.'

Some students also reported in the open-ended responses that lectures at the end of their studies allowed them to merge their practical and academic knowledge at a higher level than had been possible in earlier stages of their studies.

Discussion

The overall response rate in this study is very similar to response rates of other studies with psychiatry students. In studies by Kuhnigk et al.,[11,13] response rates of 86%, 88% and 93% were obtained where the 'attitudes towards psychiatry' questionnaire (ATP-30) was administered. In a study by Dixon et al.[14]on medical students' attitudes to psychiatric illness in primary care, the response rate was 88%. The high response rate in our study could partly be explained by the system of paper-based, standardised, regular feedback built into the six-year medical programme.

The higher number of female respondents in our study correlates with the national and international 'feminisation' trend of increased female enrolments for medical studies.[10,13,23,24] There were fewer junior 5th-year respondents than senior respondents, which reflects the spread of clinical rotations over a period of 18 months, starting in the middle of the 5th year. The absence of significant differences between the different scores for male and female, junior and senior students, or for the rotations at different times of the year is indicative of the common exposure that would be expected in a psychiatry training setting. No reasonable explanation could be found for the significant differences regarding a variety of specific scores or items other than the unpredictability of the teaching and learning opportunities that students encounter during a clinical rotation, and changes made to the programme in the course of time due to changing demands and requirements.

Disorders to which <50% of students had been exposed to, namely social anxiety, panic, obsessive compulsive and adjustment disorders, are those that general practitioners are more likely to encounter in their practice. They are also the conditions that are not always available for teaching purposes, as these patients are not institutionalised like those with more severe psychiatric conditions. No clear reason seems to exist for the continued upward trend over the years with regard to exposure to post-traumatic stress disorder. The implementation of the MHCA for involuntary patients may also have contributed to changes in the patient profile of Weskoppies Hospital, as patients who are admitted after a 72-hour assessment in a regional hospital are the severely psychotic and or suicidal patients.

Since the middle of 2009, students have also spent a week of their rotation at the psychiatric unit at the Steve Biko Academic Hospital. It is also likely that students get more exposure to psychiatric conditions commonly seen by general practitioners during their internal medicine, family medicine and district health rotations. Input from the results of this study influenced the planning of a new ward at Weskoppies Hospital for admission of different categories of patients with the conditions less commonly experienced by students.

There was a steady, significant increase in the ethics score from 2006 to 2009. This might be a result of the implementation of the provisions of the MHCA. The significantly higher exposure to confidentiality and informed consent reported by females in our study could possibly be explained by other studies that found that females had a significantly more positive attitude towards psychiatry than their male colleagues.[11,13] This inclination may have contributed to them paying more attention to issues related to confidentiality and informed consent. The significantly higher ethics exposure score for 5th-year students could, among other things, be ascribed to the fact that the junior students are exposed to these issues for the first time and may be more consciously sensitised towards ethical behaviour.

One possible explanation for the higher perception score of the 5th-year students could be that the juniors have more to learn before completing their studies and they may also still be more enthusiastic about studying than their seniors, who are more impatient to finish their studies and might also be suffering from burnout.[25-27] Students reported a lack of confidence in the questionnaire item on prescribing skills, and this component was also mentioned in the open-ended responses. Changes have already been made to the prescribing role of students in that they now write prescriptions at the in- and outpatients departments, which are co-signed by the registrar on duty. Another highly rated perception score item referred to the usefulness of the conferences with consultants. This was also confirmed in the responses to the open-ended questions. Students' positive experience of staff members also demonstrates the importance of role models.[28-32]

The students' recommendation for increasing the number of lectures was a surprising finding, as they had already completed theoretical blocks where the issues they mentioned had been addressed. The last theoretical block before the final 18-month complex starts is a pharmacotherapy block, which may explain the higher level of confidence of 5th-year students in their prescribing skills. The demand for more lectures also resonates with findings from a study by Fido and Al-Kazemi,[33] in which 83% of 6th-year medical students at Kuwait University indicated 'that well-delivered lectures were the most preferable learning method.'[33] It appears as if the content of academic lectures for the first time became 'real' to students in the practical situation. Conversely, Lampe et al.[34]found that senior medical students gave higher ratings to clinically oriented learning activities (especially tutorials with academic psychiatrists), which were considered as significantly more helpful than lectures and other non-clinical activities.[34] This corresponds with our students' positive experience of working closely with consultants.

Very little has been reported in the literature on qualitative surveys on the strengths and shortcomings of clinical clerkships in psychiatry. Lampe et al.[35] probed students on factors influencing their attitudes following an 8-week clinical attachment. The following strengths relate to some of the strengths mentioned by students in our study: a holistic perspective (approach to patients), the enthusiasm of teachers (friendly staff), good treatment of students (relaxed, student-friendly climate) and enjoying working and/or talking with people (patient exposure). Factors not mentioned in our study were the evidence-based nature of psychiatry, fascination with the complexity of the discipline and seeing patients get better. The good working relationship that students in our study had with consultants links with the perception of psychiatrists being 'seen as 'nice' people'.[35]

Study limitations and strengths

The major limitation of this study was that only one medical school was surveyed. The questionnaire focused only on certain psychiatric diagnoses, and the results did not give insights into the exposure of students to other possible diagnoses such as major depressive, somatisation and amnesic disorders. Attitudes towards psychiatry were not measured and responses were also not elicited on changes in attitudes towards psychiatry as a possible career choice. Neither did the instrument provide for the evaluation of the performance of individual teachers, as the way in which the rotation is organised does not make this a feasible option.

Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this study is the first longitudinal evaluation of a psychiatry rotation that has been reported on in SA. The conceptualisation of the tool to elicit specific scores proved to be a useful means for improving on the hands-on curriculum offerings available during a rotation. Further improvements to the tool could be made, however, by adding more of the psychiatric conditions that students might encounter during their rotation and making linkages with psychiatric conditions that they might have been exposed to in their other rotations. Using other approaches such as different forms of qualitative interviews[8,22,36] to improve on the constructs of the items that comprise the perception score could also be considered.

Combining the end-of-rotation evaluation instrument with the administration of other measures at the beginning and end of a rotation may provide a more holistic picture that could assist curriculum planners and teachers in their continuous reflection on the improvement of students' experiences in their psychiatry rotation (e.g. the ATP-30[37] or Balon et al.'s[38] questionnaire to measure students' attitudes towards psychiatry or instruments measuring the effect of a rotation on a future career choice in psychiatry). According to El-Gilany et al.,[39] '[e]xisting literature ... suggests that the quality of the psychiatry clerkship during medical school may be the most important modifiable influence on recruitment into psychiatry.' This is important in the light of the declining interest experienced in psychiatry as a career choice worldwide.[38]

Conclusion

According to Goldie,[6] evaluation entails an act of judgement of worth, and as such 'it is an inherently value-laden activity'. The evaluation given by the psychiatry students in our study was value laden and context bound. This has been demonstrated by the slight and significant differences between individual rotations and between years of study. However, the findings provide useful information for curriculum planners and teachers. As a result of the findings, a number of changes have already taken place in the organisation of the rotation, such as preparing registrars for their teaching role, selecting more appropriate topics at morning discussions, paying more attention to interpersonal skills, providing additional lectures by a specially appointed teacher, and the introduction of a rotation to another institution for more exposure to the acute conditions that generalists encounter in their practice. In the light of the anticipated increase in the number of medical students, according to the instruction of the Minister of Health,[40] similar evaluations could also assist in ensuring that larger groups of students have adequate exposure to all relevant psychiatric conditions.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to thank all the students who participated in the evaluation, and Christa Kruger and Louw Roos for their constructive comments on a draft of the manuscript.

References

1. Stein DJ, Seed S, Herman M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in South Africa. Br J Psychiatry 2008;192(2):112-117. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.029280] [ Links ]

2. Keeton C. Brain drain shrinks mental care. The Sunday Times, 24 August 2003. http://www.hst.org.za/news/20030828 (accessed 15 December 2010). [ Links ]

3. South Africa has acute shortage of psychiatrists. Pretoria News, 9 May 2005. http://www.queensu.ca/samp/migrationnews/article.php?Mig_News_ID=1039&Mig_News_Issue=5&Mig_News_Cat=8 (accessed 15 December 2010). [ Links ]

4. Speer AJ, Elnicki DM. Assessing the quality of teaching. Am J Med 1999;106(4):381-384. [ Links ]

5. Wilkes M, Bligh J. Evaluating educational interventions. BMJ 1999;318(7193):1269-1272. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj. 318.7193.1269] [ Links ]

6. Goldie J. AMEE Education Guide No. 29: Evaluating educational programmes. Med Teach 2006;28(3):210-224. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590500271282] [ Links ]

7. Zabaleta F. The use and misuse of student evaluations of teaching. Teach Higher Educ 2007;12(1):55-76. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562510601102131] [ Links ]

8. Billings-Gagliardi S, Barrett SV, Mazor KM. Interpreting course evaluation results: Insights from thinkaloud interviews with medical students. Med Educ 2004;38(10):1061-1070. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01953.x] [ Links ]

9. Johnson R. The authority of the student evaluation questionnaire. Teach Higher Educ 2000;5(4):419-434. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713699176] [ Links ]

10. Xavier M, Almeida JC. Impact of clerkship in the attitudes toward psychiatry among Portuguese medical students. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:56. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-56] [ Links ]

11. Kuhnigk O, Strebel B, Schilauske J, Jueptner M. Attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry: Effects of training, courses in psychiatry, psychiatric experience and gender. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007;12(1):87-101. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10459-005-5045-7] [ Links ]

12. McParland M, Noble LM, Livingston G, McManus C. The effect of a psychiatric attachment on students' attitudes to and intention to pursue psychiatry as a career. Med Educ 2003;37(5):447-454. [ Links ]

13. Kuhnigk O, Hofmann M, Bothern AM, Haufs C, Bullinger M, Harendza, S. Influence of educational programs on attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry: Effects of psychiatric experience, gender, and personality dimensions. Med Teach 2009;31(7):e301-e310. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590802638048] [ Links ]

14. Dixon RP, Roberts LM, Lawrie S, Jones LA, Humphreys MS. Medical students' attitudes to psychiatric illness in primary care. Med Educ 2008;42(11):1080-1087. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03183.x] [ Links ]

15. Pailhez G, Bulbena A, López C, Balon R. Views of psychiatry: A comparison between medical students from Barcelona and Medillín. Acad Psychiatry 2010;34(1):61-66. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap. 34.1.61] [ Links ]

16. Bulbena A, Pailhez G, Coll J, Balon R. Changes in the attitudes towards psychiatry among Spanish medical students during training in psychiatry. Eur J Psychiatry 2005;19(2):79-87. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632005000200002] [ Links ]

17. Sajid A, Khan MM, Shakir M, Moazam-Zaman R, Ali A. The effect of clinical clerkship on students' attitudes toward psychiatry in Karachi, Pakistan. Acad Psychiatry 2009;33(3):12-14. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.33.3.212] [ Links ]

18. S0rensen H0if0dt T, Sexton H, Olstad R. Experiences from psychiatric rotation for pre- registration house officers: Contributions to subjective learning. Med Educ 2004;38(4):349-357. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01796.x] [ Links ]

19. Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). Education and Training of Doctors in South Africa. Undergraduate Medical Education and Training. Guidelines by the Medical and Dental Professions Board. Pretoria: HPCSA, 1999. [ Links ]

20. Republic of South Africa. Mental Health Care Act No. 17 of 2002. Government Gazette, 2002;49(24024):1-78. [ Links ]

21. Krantz-Girod C, Bonvin R, Lanares J, et al. Stability of repeated student evaluations of teaching in the second preclinical year of a medical curriculum. Assess Eval Higher Educ 2004;29(1):123-133. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0260293032000158207] [ Links ]

22. Kember D, Leung DYP. Establishing the validity and reliability of course evaluation questionnaires. Assess Eval Higher Educ 2008;33(4):341-353. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930701563070] [ Links ]

23. Kent A, de Villers MR. Medical education in South Africa - exciting times. Med Teach 2007;29(9):906-909. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701832122] [ Links ]

24. Wildschut AC. Motivating for a gendered analysis of trends within South African medical schools and the profession. S Afr J Higher Educ 2008;22(4):920-932. [ Links ]

25. Jennings ML. Medical student burnout: Interdisciplinary exploration and analysis. J Med Humanit 2009;30(4):253-269. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10912-009-9093-5] [ Links ]

26. Brazeau CMLR, Schroeder R, Rovi S, Boyd L. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med 2010;85(10):S33-S36. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47] [ Links ]

27. Santen SA, Holt DB, Kemp JD, Hemphill RR. Burnout in medical students: Examining the prevalence and associated factors. South Med J 2010;103(8):758-763. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e6d6d4] [ Links ]

28. Joubert PM, Krüger C, Bergh A-M, et al. Medical students on the value of role models for developing 'soft skills' - 'That's the way you do it'. S Afr Psychiatry Rev 2006;9:28-32. [ Links ]

29. Lynoe N, Lofmark R, Thulesius HO. Teaching medical ethics: What is the impact of role models? Some experiences from Swedish medical schools. J Med Ethics 2008;34(4):315-316. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jme.2007.021147] [ Links ]

30. McLean M. The choice of role models by students at a culturally diverse South African medical school. Med Teach 2004;26(2):133-141. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590310001653973] [ Links ]

31. Passi V, Johnson S, Peile Ed, Wright S, Hafferty F, Johnson N. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME guide no. 27. Med Teach 2013;35(9):e1422-e1436. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.806982] [ Links ]

32. Basco WT, Reigart JR. When do medical students identify career-influencing physician role models? Acad Med 2001;76(4):380-382. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200104000-00017] [ Links ]

33. Fido A, Al-Kazemi R. Effective method of teaching psychiatry to undergraduate medical students: The student perspective. Med Principles Pract 2000;9(4):255-259. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000054252] [ Links ]

34. Lampe L. Coulston C, Walter G, Mahli G. Up close and personal: Medical students prefer face-to-face teaching in psychiatry. Australas Psychiatry 2010;18(4):354-360. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3.109/10398561003739620] [ Links ]

35. Lampe L, Coulston C, Walter G, Mahli G. Familiarity breeds respect: Attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry following a clinical attachment. Australas Psychiatry 2010;18(4):349-353. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3.109/10398561003739612] [ Links ]

36. Matthew SM, Taylor RM, Ellis RA. Students' experiences of clinic-based learning during a final year veterinary internship programme. Higher Educ Res Dev 2010;29(4):389-404. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294361003717903] [ Links ]

37. Burra P, Kalin R, Leichner P, Waldron JJ, et al. The ATP 30-a scale for measuring medical students' attitudes to psychiatry. Med Educ 1982;16(1):31-38. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1982.tb01216.x] [ Links ]

38. Balon R, Franchini GR, Freeman PS, Hassenfeld IN, Keshavan MS, Yoder E. Medical students attitudes and views of psychiatry: 15 years later. Acad Psychiatry 1999;23(1):30-36. [ Links ]

39. El-Gilany AH, Amr M, Iqbal R. Students' attitude toward psychiatry at Al-Hassa Medical College, Saudi Arabia. Acad Psychiatry 2010;30(1):71-74. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.34.1.71] [ Links ]

40. Mclea H, Grobbelaar R. Varsities to produce more medics. The Times, 21 June 2011:7. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A-M Bergh (anne-marie.bergh@up.ac.za)