Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Psychiatry

versión On-line ISSN 2078-6786

versión impresa ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.21 no.1 Pretoria feb. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajp.394

ARTICLES

Rape victim assessment: Findings by psychiatrists and psychologists at Weskoppies Hospital

K CoetzeeI; G LippiII

IBA, BA (Hons) (Psych), MA (Clin Psych); Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, and Forensic Unit, Weskoppies Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

IIMB ChB, FCPsych (SA), MMed (Psych); Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, and Forensic Unit, Weskoppies Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: A significant increase in rape victim assessment referrals by the courts has been noted in recent years at Weskoppies Hospital. Rape victims are referred by courts to determine: (i) their competency as a witness; (ii) their ability to give consent to sexual acts; (iii) their mental age; and (iv) their level of mental retardation. These evaluations are done by psychologists and psychiatrists at state hospitals. The findings are reported to the courts in a report format.

OBJECTIVES: To present the findings of the reports compiled by psychologists and psychiatrists on rape victims from 2009 to 2013 as they comment on the court's referral questions, and compare these findings with similar studies done at other psychiatric institutions.

METHODS: A total of 108 reports was obtained from the electronic database at Weskoppies Hospital. The findings of the reports were summarised on a datasheet and were categorised according to the referral questions of the courts.In the 68 reports where mention was made of mental age, almost three-quarters found it to be between 4 and 12 years. Intellectual disability was found as the diagnosis in the vast majority of reports. Of these, the most common severity of impairment was moderate (n=22, 21.8%) and moderate to severe (n=21, 20.8%) in nature. Most reports (n=61, 56.6%) found that the rape victims were not able to consent to sexual intercourse. Seventy-one (65.7%) reports stated that victims were not able to testify in court.

CONCLUSION: Most reports stated that victims suffered from intellectual disability and their capacity to testify in court was impaired. More than half of the victims evaluated did not have the capacity to give consent to sexual acts.

At Weskoppies Hospital, victim evaluations are done by psychologists and psychiatrists. The evaluating psychologist or psychiatrist may be subpoenaed to testify in court about their findings during trial proceedings. The findings of such evaluations are sent to the courts in the form of reports. The reports serve as expert evidence in court regarding the victim's mental state. Before reporting on the findings in these reports, we should pay attention to the challenges inherent in evaluating intellectually disabled victims and the relevant definitions of the areas of functioning on which the courts ask an opinion; the clinician is required to consult both South African (SA) legal definitions as well as internationally accepted psychiatric and psychological definitions.

A major factor in the assessment of victims with intellectual disability is the nature and level of intellectual disability present. Persons with intellectual disability often exhibit impairment in their ability to communicate their distress clearly and accurately relay an experience of a specific event. This may complicate the clinician's task in gaining a clear understanding of the victims' experience of the rape incident and assessing their overall mental state.

A second major challenge is the limitation of the ability to use formal psychometric instruments to assess intellectual disability. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V)[1] recommends that specifiers indicating the severity of intellectual disability be based on an individual's adaptive functioning rather than an intelligence quotient (IQ) score, and supports this recommendation by indicating that adaptive functioning determines the level of support an individual requires, and that IQ scores are less valid at the lower end of the IQ range.

The assessment of rape victims is a sensitive matter and poses a number of challenges to the clinician. Rape victims are often traumatised by their experience, and this can make them reluctant to talk about the incident. In a study done by Elklit et al.,[2] it was found that ~70% of sexual assault victims experienced significant levels of traumatisation, with 45% reporting symptoms consistent with a probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. In an SA study by Shabalala,[3] it was found that victims with intellectual disability were particularly at risk of developing PTSD after experiencing a traumatic incident, because of factors related to their disability. The evaluators also suggested that the collateral reports given by caregivers regarding the victims' functioning may well underreport trauma-related symptoms. In addition, Au et al.[4]found that cooccurring and comparably severe PTSD and depression symptoms are pervasive among female sexual assault survivors.

The courts usually seek clarity on four areas of a suspected mentally disabled victim's functioning, namely the victim's:

- mental age

- level of mental retardation

- ability to consent to sexual acts

- competency as a witness/ability to testify in court proceedings.

Mental age

Weschler[5] commented in The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence that mental age is a term first used by French psychologist Alfred Binet, who introduced the intelligence test in 1905. The term was then used to define different degrees or levels of intelligence. This presupposed that intellectual ability could be measured and that it increased with age. Binet devised a series of graded intellectual tasks whereby intelligence could be measured, and described a mode of evaluating the results in terms of age units such that the average child of 6 years old might be said to have a mental age of 6 years old. This technique of scoring tests in terms of age units came to be known as the mental age method, and the scores obtained by this method as mental ages. Originally, the differences between mental age and chronological age were used to compute IQ. Modern intelligence tests no longer compute scores using the IQ formula. Instead, intelligence tests give a score that reflects how far the person's performance deviates from the average performance of others who are the same age.

Mental retardation/intellectual disability

According to the DSM, 4th edition (text revised) (DSM-IV-TR),[6] a diagnosis using the term mental retardation is made if an individual has significantly below-average intellectual functioning, as defined by an IQ <70. In addition, limitations in adaptive functioning are present in at least two of the following skill areas: communication, home living, self-care, self-direction, use of community resources, functional academic skills, social/interpersonal skills, work, leisure, health and safety. The onset must occur before the age of 18 years. The DSM-IV-TR classifies mental retardation into four stages based on severity: mild (IQ 50 - 55 to ~70), moderate (IQ 35 - 40 to 50 - 55), severe (IQ 20 - 25 to 35 - 40) and profound (IQ <20 - 25).

The DSM-V[1] has adopted the term intellectual disability as opposed to the term mental retardation. The reasoning behind this is that the term intellectual disability is used in research, education and legal fields and has become the more acceptable term. The American Psychiatric Association[6] categorises intellectual disability into three domains, namely conceptual, social and practical. In moving away from the DSM-IV-TR's apparent emphasis on IQ scores as indications of severity of intellectual impairment, the association defines the various levels of severity on the basis of adaptive functioning and not IQ scores, because adaptive functioning determines the level of support required. They also comment that IQ measures are less valid at the lower end of the IQ range.

The Mental Health Care Act No. 17 of 2002[7] defines 'severe or profound intellectual disability' as a range of intellectual functioning extending from partial self-maintenance under close supervision, together with limited self-protection skills in a controlled environment through limited self-care and requiring constant aid and supervision, to severely restricted sensory and motor functioning and requiring nursing care.

In a study done by Pillay[8] at Fort Napier Hospital, it was found that in 106 cases that presented over a 3-year period ending in 2008, 16 (15.1%) cases were diagnosed with mild mental retardation, 43 (40.6%) with moderate mental retardation, 41 (38.7%) with severe mental retardation and 2 (1.9%) cases with profound mental retardation. Four (3.8%) cases were not classified with mental retardation. Calitz et al.[9]found in a study conducted at the Free State Psychiatric Complex that in 137 cases that presented over a 7-year period from 2003 to 2009, 20 (14.6%) were diagnosed with mild mental retardation, 92 (67.2%) with moderate mental retardation and 25 (18.3%) with severe mental retardation. No cases were diagnosed with profound mental retardation.

Ability to consent to sexual acts

The Sexual Offences and Related Matters Act No. 32 of 2007[10] defines a person with mental disability as a person affected by any mental disability, including any disorder or disability of the mind, to the extent that he or she at the time of the alleged commission of the offence in question was:

- unable to appreciate the nature and reasonably foreseeable consequences of a sexual act

- able to appreciate the nature and reasonably foreseeable consequences of such an act, but unable to act in accordance with that appreciation

- unable to resist the commission of any such act

- unable to communicate his or her unwillingness to participate in any such act.

Under these circumstances, such a mentally disabled person would be found to be incapable of consenting to a sexual act.

In a study addressing the capacity of people with intellectual disability to give consent to sexual acts, Murphy and O'Callaghan[11] found that these adults were significantly less knowledgeable about almost all aspects of sex, and appeared significantly more vulnerable to abuse, having difficulty at times distinguishing abusive from consenting relationships. However, some adults with intellectual disabilities did show knowledge of sex and sexual relations in most areas, especially if they had relatively high IQs and had had sex education.

Calitz et al.[9]found that most participants in their study (98.5%) were unable to give consent to sexual intercourse, with only 1.5% found to be able to do so.

Pillay[8] found that in 65.1% of cases, the victims were not capable of making an informed decision to consent to sexual intercourse. This figure included children below the statutory age of consent.

Competency as a witness/Ability to testify in court proceedings

A person's ability to testify in court or competency as a witness is defined by the Criminal Procedures Act No. 51 of 1977,[12] which states that 'no person appearing or proved to be afflicted with mental illness or to be labouring under any imbecility of mind due to intoxication or drugs or the like, and who is thereby deprived of the proper use of his reason, shall be competent to give evidence while so afflicted or disabled'. This Act thus makes provision for assessments assessments of a person's ability to testify in court or competency as a witness, but typically presents a legal definition that leaves room for interpretation within the clinical context, and uses inaccurate and outdated medical terms such as 'imbecility'.

Kebbell et al.[13]commented on the examination in court of the testimony of people with intellectual disability. They stated that the way in which witnesses are examined in court does little to ensure that their memories are as accurate as possible. People with intellectual disabilities should be questioned in such a way that their ability to give accurate evidence in court is maximised. They also point to the fact that often the increased suggestibility of witnesses with intellectual disabilities is exploited by suggestions that they are lying or have an inaccurate memory. In addition, they noted that the questioning of witnesses with intellectual disabilities was almost identical to that of witnesses from the general population, indicating that lawyers are not altering their questioning behaviour for witnesses with intellectual disabilities. Pillay[14] argued that every attempt must be made to find reasons why intellectually disabled victims should be permitted to give evidence in the first place rather than why they should not be allowed to testify. He also calls for a more user-friendly legal system, especially with regards to the intellectually disabled.

In a recent study, Phaswana et al.[15]found in their sample of rape victims referred for evaluation by the court that 53.6% could testify in court and 46.4% were unable to do so. In addition, they found two significantly associated variables associated with the victims' ability to testify, namely the residential category of the victim and the level of mental retardation of the victim. Victims from rural areas and victims with severe mental retardation were significantly more often found to be unable to testify in court.

Calitz et al.[9]found that of 137 cases, only one victim could testify in court. This victim was diagnosed with mild mental retardation. The rest of the cases (98.5%) were found to be unable to testify in court, and had diagnoses of mild, moderate or severe mental retardation.

Objective

The objective of the current study was to present the findings in the reports compiled by psychologists and psychiatrists at Weskoppies Hospital, following evaluations of rape victims evaluated between 2009 and 2013, more specifically as they relate to the court's referral questions. A second objective was to draw a comparison between the study findings and those of similar studies done at other psychiatric institutions.

Methods

The current study took a retrospective and descriptive approach to the data gathered.

The data were obtained from the reports written by psychologists and psychiatrists at Weskoppies Hospital during the period 2009 - 2013. A total of 108 reports were written during this period. These reports were accessed via the hospital's electronic database.

The reports were summarised on a data-capturing sheet according to different categories mentioned in the reports, namely age, gender, race, home language of the victim, reason for referral, assessment method and the use of interpreters. The report findings were categorised according to the following referral questions: (i) competency as a witness; (ii) ability to give consent to sexual acts; (iii) mental age; and (iv) level of mental retardation.

Approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria. Permission to access the hospital's electronic database was granted by the chief executive officer of Weskoppies Hospital.

Results

In the reports, mention is made that assessments of each victim included interviews with the victim as well as with their family members, when possible, perusal of the information contained in the legal documents, and psychometric testing, where possible. In some cases the use of an interpreter was required.

Sociodemographic features

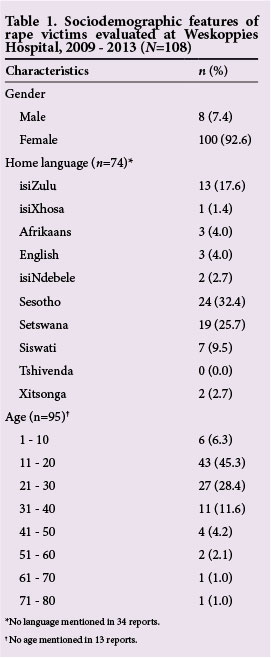

During the 5-year period between 2009 and 2013, 108 rape victim reports were written. Table 1 summarises the victims' sociodemographic information. Of the 108 rape victims assessed, 8 (7.4%) were male and 100 (92.6%) were female. Only 74 reports make mention of the victim's home language. The most commonly spoken home languages were Sesotho (n=24, 32.4%), Setswana (n=19, 25.7%) and isiZulu (n=13, 17.6%). In 34 (31.48%) reports, no mention was made of the victim's home language.

The victims' age ranged from 6 to 77 years, with most victims (45.3%) falling in the 11 - 20-year age group. The second largest age group was between 21 and 30 years (28.4%) followed by the 31 - 40-year age group (11.6%). In 13 (13.7%) reports, there was no mention of the victim's age.

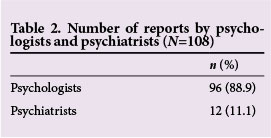

Number of reports by psychologists and psychiatrists

Of the 108 reports, 96 (88.9%) were written by psychologists and 12 (11.1%) were written by psychiatrists (Table 2).

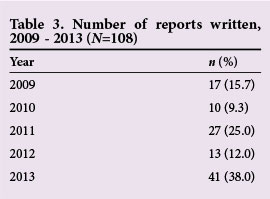

Number of reports written, 2009 - 2013

Seventeen reports were written in 2009 (15.7%) and 10 (9.3%) in 2010 (Table 3). A substantial increase (n=27, 25%) in the number of reports written occurred in 2011, which produced a quarter of the reports analysed in the study. A decrease occurred in 2012, with the total number of reports written for that year totalling 13 (12%).

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the number of rape victim referrals to Weskoppies Hospital. During the period 2009 - 2014, victims have been referred from Mpumalanga and Gauteng provinces to Weskoppies Hospital for evaluation.

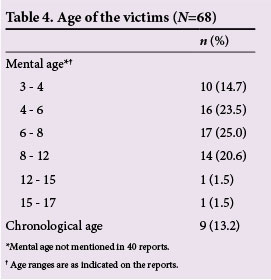

Mental age of the victims

A quarter of the reports that commented on the victims' mental age found that they had a mental age of between 6 and 8 years (25.0%) (Table 4). The next most prevalent mental age group was the 4 - 6-years group (23.5%). Fourteen (20.6%) victims fell within the 8 -12-year mental age range. The vast majority of reports (58.8%) did not comment on the victims' mental age.

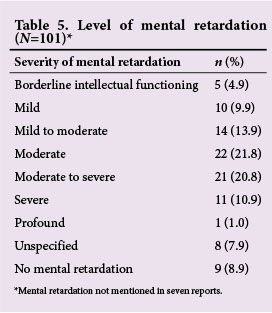

Level of mental retardation

In most cases, (n=22; 21.8%) the rape victims were diagnosed with moderate mental retardation; this was followed closely by moderate-to-severe mental retardation (n=21, 20.8%) (Table 5). The third most prevalent diagnosis was mild-to-moderate mental retardation (n=14, 13.9%) and the fourth was severe mental retardation (n=11, 10.9%) followed closely by mild mental retardation (n=10, 9.9%). Five (4.9%) victims were diagnosed with borderline intellectual functioning. In 9 (8.9%) cases, rape victims were found not to have a diagnosis of mental retardation. In 8 (7.9%) cases, unspecified mental retardation was diagnosed. Seven (6.4%) reports did not mention mental retardation.

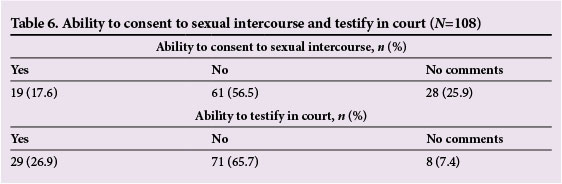

Ability to consent to sexual intercourse and testify in court

Most reports (n=61, 56.6%) found that the rape victims were not able to consent to sexual intercourse (Table 6). In 19 (17.6%) of the cases, they were found to be able to give consent to sexual intercourse. No comments were made regarding the victim's ability to consent to sexual intercourse in 28 (25.9%) cases. On the victim's ability to testify in court, 29 (26.9%) of the reports found victims able to testify in court and 71 (65.7%) found them to be unable to. In 8 (7.4%) reports, no comments were made regarding the victim's ability to testify in court.

Discussion

The results indicated that the referrals from the court for the evaluation of rape victims were appropriate. As was reported by Calitz[16] at the Free State Psychiatric Complex in Bloemfontein, an increase in referrals for rape victim assessments (Table 3) was also found at Weskoppies Hospital, as is highlighted in this study.

From the results it also seems that there is a lack of collateral information in the assessments. In the assessment of intellectual impairment, it is crucial that collateral information be obtained before a diagnosis is made. As many of the victims were only accompanied by police officers or family members who do not necessarily have the ability to give an accurate history of the victim's intellectual functioning, it is up to the clinician to ensure that such information is obtained before a diagnosis is made. Of particular interest would be school reports or first-hand reports of the primary caregivers, commenting on the victim's level of functioning. In addition, more use can be made of psychometric instruments to measure intellectual and adaptive functioning. In only 5 (8%) of the reports analysed, mention was made of the use of additional psychometric testing to support the clinical findings. The use of adaptive behaviour scales and intellectual assessment instruments might aid in coming to a proper diagnosis that may increase the weight that such a report carries in court proceedings.

With regard to the age ranges, it is noteworthy that more than half of the victims were either children or teenagers, while more than three-quarters were under the age of 30. This finding suggests that the most vulnerable age groups to fall victim to sexual offences are children, adolescents and young adults. Victim profile and perpetrator profile and report rates may influence these results.

As part of rape victim assessments, the courts request opinion on the mental age of the victims. Mental age was initially used to calculate level of intelligence compared with that of others of the same chronological age. More recently, IQ scoring has become the more relevant and accepted way of measuring intelligence, as is evidenced by its incorporation in diagnostic criteria of intellectual disability. Furthermore, the emphasis of intellectual disability evaluation has shifted in the direction of evaluation of adaptive functioning. In light of this, we argue that having to comment on mental age as part of a rape victim assessment is outdated, unnecessary and may be misleading to the courts. The core questions that the court asks can be answered without having to refer to mental age. This might explain why so many of the evaluated reports made no mention of mental age.

Of the reports, 91% found that the victims suffered from intellectual impairment. A wide range of severity of intellectual disability was found in this study, compared with the study by Calitz et al.,[9]who found that around two-thirds of their victim population were moderately intellectually disabled. Many possible variables could explain the difference in the findings at the two different sites.

More than half of the assessed reports gave an opinion that the victim did not have the ability to consent to sexual acts, while only 17.6% could do so. This finding is significantly higher than Calitz et al.[9] found in their study, namely that only 1.5% of the victims were able to consent to sexual intercourse. It is noteworthy that more than a quarter of the reports did not comment on the victim's ability to consent to sexual acts even though the courts specifically requested it. The reasons behind this surprising finding should be explored in a future study.

The results of this study revealed that just over a quarter of the victims were found to be able to testify in court, but that a majority (almost two-thirds) could not. These findings are in stark contrast to those of Calitz et al.,[9] who found that more than 99% of their victim sample were unable to testify. Calitz et al.[9]found that regardless of level of intellectual functioning, most of their assessed rape victims could not testify in court, whereas the current study found that some victims could testify in spite of suffering from varying degrees of intellectual disability. There are many possible variables that could play a role in the differing opinions at these sites.

Future studies may focus on specific assessment methods as well as the relationships between severity of intellectual disability, ability to consent to sexual acts and the ability to testify in court, which are limitations of the present study.

Conclusion

Rape victim assessment reports play an important part in court proceedings. Victims often suffer from intellectual disability, which impairs their ability to contribute to court proceedings or give consent to sexual intercourse. More emphasis can be placed on obtaining collateral information in the assessment of these victims.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. USA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [ Links ]

2. Elklit A, Christiansen DM. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in female help- seeking victims of sexual assault. Violence Vict 2013;28(3):552-568. [ Links ]

3. Shabalala N. PTSD symptoms in intellectually disabled victims of sexual assault. S Afr J Psychol 2011;41(4):424-436. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124631104100403] [ Links ]

4. Au TM, Dickstein BD, Comer JS, Salters-Pedneault K, Litz, BT. Co-occurring post-traumatic stress and depression symptoms after sexual assault: A latent profile analysis. J Affect Disord 2013;149:209-216. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.026] [ Links ]

5. Weschler D. The Measurement and Appraisal of Adult Intelligence. 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company, 1958. [ Links ]

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision (DSM-IV TR). USA: American Psychiatric Association, 2004. [ Links ]

7. Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Republic of South Africa. Mental Health Care Act No. 17 of 2002. Cape Town: Juta & Co, 2002. [ Links ]

8. Pillay AL. An audit of competence assessments on court-referred rape survivors in South Africa. Psychol Rep 2008;103:764-770. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.103.3.764-770] [ Links ]

9. Calitz FJW, de Ridder L, Pretorius A, Smit J, Joubert G. Profile of rape victims referred by the court to the Free State Psychiatric Complex, 2003 - 2009. S Afr J Psychiatr 2014;20(1):2-6. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajp.459] [ Links ]

10. Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Republic of South Africa. Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act No. 32 of 2007. Cape Town: Juta & Co, 2007. [ Links ]

11. Murphy G, O'Callaghan A. Capacity of adults with intellectual disabilities to consent to sexual relationships. Psychol Med 2004;34(7):1347-1357. [ Links ]

12. Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Republic of South Africa. Criminal Procedures Act No. 51 of 1977. Cape Town: Juta & Co, 2010. [ Links ]

13. Kebbell MR, Hatton C, Johnson SD. Witnesses with intellectual disabilities in court: What questions are asked and what influence do they have? Legal and Criminological Psychology 2004;9(1):23-35. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/135532504322776834] [ Links ]

14. Pillay AL. The rape survivor with an intellectual disability v. the court. S Afr J Psychol 2012;42(3):312-322. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124631204200303] [ Links ]

15. Phaswana TD, van der Westhuizen D, Kruger C. Clinical factors associated with rape victims' ability to testify in court: A records-based study of final psychiatric recommendation to court. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesburg) 2013;16(5):343-348. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v16i5.46] [ Links ]

16. Calitz FJW. Psycho-legal challenges facing the mentally retarded rape victim. S Afr J Psychiatr 2011;17(3):2-6. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

K Coetzee (kobus.coetzee@up.ac.za)