Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Psychiatry

On-line version ISSN 2078-6786

Print version ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.20 n.4 Pretoria Oct./Dec. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajp.536

ARTICLE

Positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia as correlates of help-seeking behaviour and the duration of untreated psychosis in south-east Nigeria

P C OdinkaI; A C NdukubaI; R C MuomahII; M OcheIII; M U OsikaIV; M O BakareV; A O AgomohV; R UwakweVI

IMBBS, FWACP (Psych); Department of Psychological Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria

IIPhD; Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria

IIIMBBS, FWACP (Psych); Department of Psychological Medicine, Federal Medical Centre Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria

IVMBBS, FMCPsych; Psychiatric Hospital, Rumuigbo Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

VMBBS, FMCPsych; Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, New Haven, Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria

VIMBBS, FWACP (Psych), FMCPsych; Department of Mental Health, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) has been widely recognised in recent years as a potentially important predictor of illness outcome, and the manifestations of schizophrenia have been known to influence its early recognition as a mental illness.

OBJECTIVE: To assess the association between the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, help-seeking and DUP.

METHODS: We performed a cross-sectional study of 360 patients with schizophrenia, who had had no previous contact with Western mental health services. The Sociodemographic Questionnaire, World Health Organization Pathway Encounter Form and a questionnaire to establish DUP were used. The positive and negative syndrome scale and Composite International Diagnostic Interview were used for the assessment of mental disorders and to diagnose.

RESULTS: Respondents who had predominant positive symptoms and who had a median DUP of 8 weeks or 24 weeks, tended to use psychiatric hospitals and other Western medical facilities, respectively, as their first treatment options. However, those who had predominant negative symptoms and who had a median DUP of 144 weeks or 310 weeks, tended to use faith healers and traditional healers, respectively, as first treatment options.

CONCLUSION: The predominance of negative symptoms could militate against early presentation among people with schizophrenia, probably because negative symptoms are poorly recognised as indicating mental illness in Nigeria, as they could be interpreted as deviant behaviour or spiritual problems that would require spiritual solutions.

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder that usually manifests as a predominant negative symptoms (PNS), severe psychotic illness with onset in early adulthood, characterised by bizarre delusions, auditory hallucinations, thought disorder, strange behaviour and progressive deterioration in personal, domestic, social and occupational competence, all occurring in clear consciousness.[1] It is among the leading causes of long-term disability in the world,[2] and is the single most important cause of chronic psychiatric disability,[1] contributing about 1.1% of the global disability-adjusted life years.[3]

The presentation of schizophrenia in hospital is usually preceded by a period during which the psychosis may not be adequately recognised and treated. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is understood as a period from the development of the first symptoms of psychosis to the commencement of appropriate intervention measures, such as antipsychotic drug treatment.[4] DUP has been widely recognised in recent years as a potentially important predictor of illness outcome in schizophrenia,[5] which has raised the issue of the importance of early detection and intervention for people developing psychotic illness.[6] For instance, treatment delay has been reported to have deleterious effects,[7] with consequent worsening of the prognosis;[8] reducing delays in early detection and treatment might improve long-term outcome.[9,10]The significance of early detection of mental health disorders in the population, therefore, cannot be overemphasised in view of increasing the opportunity to benefit from professional intervention.[11]

The symptoms that manifest early in schizophrenia could influence the interpretation of the illness and, therefore, the type and time of help-seeking. For instance, positive symptoms could be more readily identified as indicating mental illness than negative symptoms,[12] and patients with PNS may more readily consult with a traditional healer first, which could lead to a long DUP.[13,14]Positive symptoms of schizophrenia reflect an excess or distortion of normal functions, while negative symptoms refer to a decrease in or absence of characteristics of normal function. Erritty and Wydell[15] noted that positive symptoms were perceived as more discernible signs of mental illness than negative symptoms by a lay population. It was also observed that rapid access to mental health services could occur when the first signs of psychotic features are severe, including aggressive or violent behaviour.[14,16]

Erritty and Wydell,[15] as well as Addington et al.,[17] also opined that people generally do not confidently recognise some negative symptoms as signs of mental illness and would not necessarily consider professional healthcare a priority for these symptoms, but the reverse is most likely to be the case when there is a predominance of positive symptoms. This becomes more disheartening against the backdrop that people with a DUP <1 year show substantially greater negative symptom reduction, especially when DUP is <9 months, compared with those with a DUP of >1 year.[18]

There is no established treatment for primary negative symptoms,[19,20]even though some treatments such as antipsychotics,[21] and some psychosocial treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy,[22] peer support groups,[23] music therapy[24] and body-oriented psychosocial therapy[25] have all been shown to have some positive effect on negative symptoms; however, positive effects are better felt when the DUP is <1 year, especially <9 months.[18]

Since there is no effective treatment for negative symptoms[19,20]and perceptions of the symptoms of schizophrenia can influence the time and the type of help-seeking (and with early treatment positively influence the outcome),[7,26]reducing DUP to <1 year may be, for now, the best way to ameliorate the problems.[18] Understanding the influence of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia in help-seeking behaviour and its relationship to DUP is important as this can facilitate the planning and implementation of early, effective interventions.

The current study is designed to assess the relationship between the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, help-seeking behaviour and DUP. Although the influence of positive and negative symptoms on DUP and treatment delay has been covered by numerous articles during the last 15 - 20 years, the objectives of this current study were mainly to bring out the south-east Nigerian perspective.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Enugu, Enugu State, south-east Nigeria. The hospital is the only Federal Government-owned psychiatry hospital in the south-east, and provides psychiatric services to residents of Enugu State; it also receives referrals from and beyond all five south-eastern states of Nigeria. South-eastern Nigeria (one of the six geopolitical zones or divisions in which Nigeria's 36 federating units or states are grouped) is primarily inhabited by people of the Igbo ethnic group, who speak Igbo and comprise one of the three largest and most influential ethnic groups in Nigeria. The Central Intelligence Agency in the USA[27] put the Igbo population at 18% of the total Nigerian population of 170 million, i.e. approximately 30 million. Igbo people were mainly adherents of African Traditional Religion (ATR) following colonisation; however, the influence of ATR in south-east Nigeria has dwindled, and Igbo people have become predominantly Christians.

Ethics

Approval for the study was obtained from the ethical committee of the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Enugu. Written informed consent was also obtained from patients or their next-of-kin before the study instruments were administered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥15 years, who met International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)[28] diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia and who had no previous history of contact with any Western mental healthcare facility were included. Patients who had sought care from Western medical facilties and who were additionally probably exposed to psychotropic medication were excluded from the research. This information was either through self-report or family report.

Sample identification and recruitment procedures

Recruitment of participants was done at the wards and emergency clinic of the Federal Neuropsychiatry Hospital Enugu, and the hospital holds emergency clinics every day of the week. Outpatients were interviewed on the first day of contact, while admitted patients were interviewed within 48 hours of admission. All consecutive patients who came to the emergency clinic with a diagnosis of schizophrenia between May 2010 and January 2011, who met the inclusion criteria, were recruited into the study. The patients were first seen by trainee psychiatrists, who after making a diagnosis of schizophrenia, sought patient consent to participate in the study. Patient response did not in any way influence the treatment they received. The authors were informed only about the patients who gave their consent to participate in the research, and then recruited them into the study after seeking and obtaining their consent for a second time. A total of 369 subjects were enrolled; however, two changed their mind after recruitment for no obvious reason, and seven were excluded for not meeting the criteria. The high rate of participation could be because apart from patients' initial interaction with the trainee psychiatrists, the authors also took time to talk to the patients about the illness and the relevance of the study.

Instruments

The World Health Organization (WHO) Pathway Encounter Form, adapted from the Encounter Form developed for the WHO's cross-cultural study on pathways to mental healthcare,[29] and an adapted questionnaire[30] were used to establish the DUP. A sociodemographic questionnaire designed for this study, eliciting age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, employment status and area of residence, was administered.

Patients' current mental state was assessed using the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS).[31] The PANSS, a 30-item, 7-point rating instrument, is scored by summation of ratings across items, such that the potential ranges are 7 - 49 for the positive and negative scales, respectively, and 16 - 112 for the general psychopathology scale. The composite scale is arrived at by subtracting the negative from positive score, thus yielding a bipolar index that ranges from -42 to +42.[31] Using the PANSS, patients with schizophrenia were classified with predominant positive symptoms (PPS) or PNS, according to the valence of their composite scale score.

The positive symptoms included seven symptom clusters: delusions, conceptual disorganisation, hallucinatory behaviour, excitement, grandiosity, suspiciousness/persecution and hostility. The negative symptoms also included seven symptom clusters: blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, passive/apathetic social withdrawal, difficulty in abstract thinking, lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation, and stereotyped thinking.

Each item on the PANSS includes a complete definition and detailed criteria for all seven rating points, which represent increasing levels of psychopathology: 1 = absent, 2 = minimal, 3 = mild, 4 = moderate, 5 = moderate-severe, 6 = severe, and 7 = extreme.

The general psychopathology scale was included as an important adjunct to the positive-negative assessment to provide a separate but parallel measure of the severity of schizophrenic illness, which could serve as a point of reference, or control measure, for interpreting the syndromal scores.[31]

The Munich version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI),[32] which was produced for the WHO and the US Alcohol Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration by the US National Institute for Mental Health, was used for the assessment of mental disorders and to provide diagnoses according to ICD-10.[28]

Data-collection procedures

The patients were interviewed by two of the eight authors (PCO or ACN), who are both psychiatrists. Both had previous training in the administration of the instruments and inter-rater reliability was satisfactory (r=0.86).

Patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia by the attending resident doctors on duty at the point of first contact at the emergency clinic had their diagnosis confirmed by using the schizophrenia module of the M-CIDI. Thereafter, the WHO Pathway Encounter Form and the PANSS were administered to participants. The DUP was established for each patient by questioning the patient and family members. An adapted questionnaire on DUP[32] was used, relating to the date and age at onset and mode of onset of the psychotic symptoms, which were ascertained by interviews with the patients and family members.

Onset of illness was determined in two ways: First, we asked patients and their family members when the patient (or family member) first experienced (or noticed) behavioural changes which, in retrospect, appeared to have been related to the patient's becoming ill; second, after explaining psychosis in clear language, we asked when the patient (or family member) first experienced (or noticed) psychotic symptoms. When differences between patient's and family members' responses occurred, a consensus decision was made by the research group.[32]

Data analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS version 16 (IBM, USA). The sociodemographic variables of the participants were presented as proportions, which were compared by means of the χ2 test. The group of participants who visited drug stores, private hospitals and general hospitals were merged to form a new group (other Western medicine groups) for clarity and easy interpretation of results.

We analysed the relationship between the raw positive score and DUP score (as a continuous variable) and between the raw negative score and DUP score (as a continuous variable). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

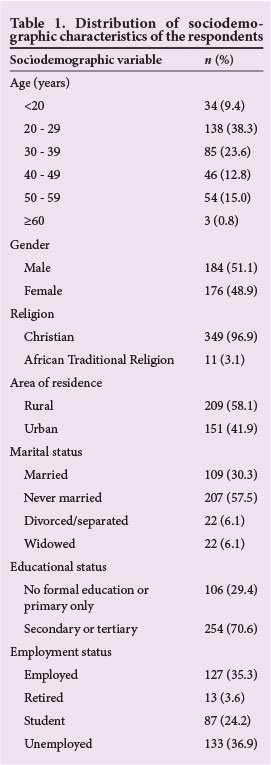

Median DUP was 48 weeks, with a mean of 111.08 (standard deviation (SD) 131.330; range 4 - 960) weeks. DUPs had a positively skewed distribution.The mean age was 34.81 (12.05) years, with 20 - 29 years being the most predominant age group. Seventy per cent of participants had at least secondary school education (Table 1).

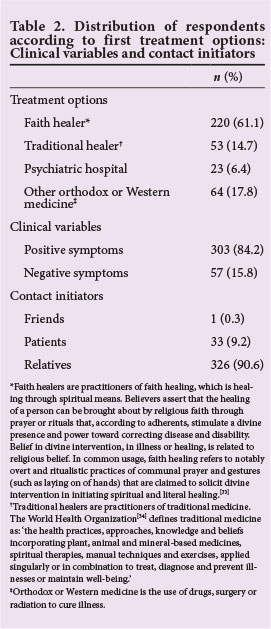

Over 75% of the patients used faith healers or traditional healers as their first treatment option, while about 6% used psychiatric services as their first treatment option. In over 90% of the cases, the relatives were the first to initiate treatment, while the patient initiated treatment in about 9% of the cases (Table 2).

Patients with a predominance of negative symptoms were significantly more likely to have used traditional and faith healers as their first treatment options compared with those with a predominance of positive symptoms, who were more likely to have used Western medical facilities as their first treatment options (χ2=13.628; df=3; p=0.003) (Table 3).

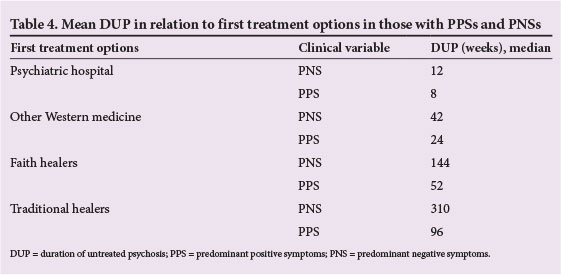

In Table 4, the median was used as the preferred measure of central tendency because the dependent variable (DUP) was very much skewed (total skewness = 2.214, much higher than 1) when compared with the means, for groups defined by the independent variables (PPS and PNS), in relation to the first treatment option used by the patients who had either PPS or PNS.

Respondents who had PPS and who had a median DUP of 8 weeks or 24 weeks tended to use psychiatric hospitals or other Western medical facilities, respectively, as their first treatment options, whereas those who had PNS and who had a median DUP of 144 weeks or 310 weeks tended to use faith healers or traditional healers, respectively, as their first treatment options. Based on this, we can say that patients who used psychiatric hospitals and other Western medical facilities first, and who also had PPS, had shorter DUPs than patients who went to faith healers and traditional healers first, and who also had negative symptoms.

There was a weak positive correlation between DUP and PNS (r=0.280; p=0.001), and a weak negative correlation between DUP and PPS (r=-0.156; p=0.003) (Table 5).

Discussion

DUP was initially defined as the period from the first clear description of psychotic phenomena, from any source, to first contact with Western mental health services and the beginning of adequate treatment.[35,36]

Studies have consistently shown intervals of 1 - 2 years between the onset of psychotic symptoms and the start of adequate treatment. [36-38] Boonstra et al.,[18] in a meta-analysis, found that shorter DUP is associated with less-severe negative symptoms at short- (1 - 2 years) and long-term (5 - 8 years) follow-up, especially when DUP is <9 months (39 weeks). The 39-week DUP early presentation mark for patients with PNS was not feasible for most of our patients. We observed that patients with PNS who first visited faith healers and traditional healers had median DUPs of 76 weeks and 96 weeks, respectively; while patients with PPS who visited psychiatric hospitals and other Western medical facilities as their first treatment choice had median DUPs of 8 weeks and 24 weeks, respectively.

We also observed that >95% of those who used Western psychiatric services as a first treatment option had PPS; this was similarly reported by Erritty and Wydell.[15] About 97% of those who used other Western medical facilities had PPS; their choice of treatment may be attributed to limited access to Western mental health services.

The mentally ill among the Igbos are referred to as onye ara (meaning 'mad person') and are typified by vagrant psychotics. Therefore, those presenting with symptoms associated with disorganised and intolerable behaviour in south-east Nigeria are more likely to be recognised as having mental illness and a need for help, whereas those exhibiting less aggressive or intolerable behaviours, even though their prognosis is poorer, may go unrecognised and unattended to. As observed by Erritty and Wydell[15] and Addington et al.,[17] people tend not to recognise confidently some negative symptoms as signs of mental illness, and most do not see those with negative symptoms as having any need for mental health services.

Most patients who manifested with PNS used traditional healers and faith healers as their first treatment options, and they also had longer DUPs; this may be explained by the cultural belief of the Igbos in agwu, which is characterised by oddities of behaviour of insidious onset and attributed to the malevolent activities of deities on an individual who has refused to serve the deities. Melle et al.[13] and Burns et al. [14] reported similar results in related studies. In contrast, those who presented with PPS had a shorter DUP, which has also been reported elsewhere.[39]

A higher percentage of participants with PNS used traditional healers (22.6%), and faith healers (19.1%) when compared with the number of participants with PNS who visited a psychiatric hospital and other Western medical facilities. Seemingly, this is not a reflection of the displacement and relegation of the ATR and its practices to the background, as currently being experienced in Igbo areas where different brands of Christian religions are flourishing. This demonstrates that healing elements of the traditional and faith beliefs may co-exist with each other, since people still go back to their traditional roots when they are faced with problems that their current Western lifestyle can not explain to them, despite a Western religious lifestyle and beliefs possibly resulting in them losing touch with their culture and tradition; this has been reported elsewhere. [40] This use of traditional healers could be said to be paradoxical, considering the fact that many people do not openly identify with traditional religious practices in the contemporary Igbo society; this may be due to social reasons as shown by the feelings of shame and fear that people exhibit when asked about traditional religion and healing, which often make it difficult, especially for Christians, to reveal their knowledge of traditional healing methods. [40]

Traditional healing methods have been used by Africans for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of social, mental and physical ailments of different origins before and even after the advent of conventional medicine.[41] However, the co-existence of traditional and Christian belief systems has been described in sub-Saharan Africa, and Christian concepts of disease, including its cause and treatment such as prayers, have been reported alongside traditional healing methods for psychosis, infertility and HIV/AIDS, among others.[42-45]

In the precolonial Igbo culture, patients who had schizophrenia with PNS would have been subjected to several rituals and reconciliatory activities, after which the community would become more tolerant of their aberrant behaviours and, in some cases, even revere them. In the postcolonial Igbo culture, however, and with the Igbos currently being adherents of predominantly the Christian religion, symptoms of mental illness are being attributed to malevolent activities of the devil rather than those of the local deity on a disobedient follower. In the present Igbo society, with the weakening of family ties and the gradual disappearance of the extended family system, the chances of early detection of individuals with mental health problems, especially those manifesting with negative symptoms, are reduced. Therefore, the impairment of functioning in patients with PNS of schizophrenia could be incapacitating and deeply entrenched due to lack of early detection and intervention.

Wrong interpretations of symptoms, as has been noted elsewhere,[16,37]could have also accounted for the delay in presenting for treatment by patients with PNS. Burns et al. [14] and Singh and Grange[46] have opined that the wrong interpretation of negative symptoms could be due to the insidious nature of onset of the illness, which could result in relatives adjusting to abnormal behaviour that they might initially have perceived as deviant. When the patient's problem manifested slowly in the deviation from daily routine, the relatives tended to regard the problem as a bad habit or character problem; such an interpretation would lead to subsequent treatment delay.[39] However, a marked change in premorbid functioning and the presence of positive psychotic symptoms facilitate help-seeking in psychiatric facilities.[46] Conversely, Srinivasan et al. [47] reported that the degree of disability and clinical symptoms (except self-neglect) were not related to taking treatment.

It has been suggested that factors such as poor public awareness and a failure to recognise negative symptoms may play an important role in delaying the initiation of treatment for psychosis. [48,49]Joa et al. [50] found in their study that the use of intensive information campaigns, educating the general public about the early signs and symptoms of schizophrenia and the importance of early intervention, significantly reduced DUPs, which raises the hope that educational efforts could have a positive impact on reducing DUP in the south-east Nigeria population. In the Nigerian context, therefore, such campaigns should, among other things, target traditional and faith healers in order to reduce the DUP and improve treatment outcomes for patients with schizophrenia.

Study strengths

Both patients and family members were interviewed about the debut of behavioural changes and other psychotic symptoms, which helped to increase the chances of the information being accurate.

The study is based in Nigeria on a large sample of previously untreated patients. In Nigerian societies, negative symptoms are poorly recognised as a mental illness, which could lead to longer DUP; the study was able to show that patients who used psychiatric hospitals and other Western medical facilities first, and who also had PPS, had shorter DUPs when compared with patients who went to faith healers and traditional healers first, and who also had PNS.

Study limitations

The evaluation of negative symptoms at the point of recruitment does not necessarily mean that the patients initially presented with negative symptoms. Retrospective examination of negative symptoms may be an alternative, but could still be problematic. The association between PNS and long DUP cannot be viewed or interpreted as causal, since this is a cross-sectional study. It may be that a long DUP leads to negative symptoms, rather than vice versa.

Recall bias could reduce the accuracy of the information. Self-reports may sometimes not reveal all details about a respondent. The study sample was selective rather than representative and focused only on patients with schizophrenia who visited the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital at the time of study. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to the entire country or population of south-east Nigeria.

Clinical implications

This study is a replication and strengthening of previous studies such as that by Burns et al.,[14] which was from a South African perspective and in which longer DUP was associated with higher negative symptoms. The originality lies mainly in the Nigerian perspective, focusing on positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia in help-seeking behaviour and DUP, since, in Nigerian societies, negative symptoms are poorly recognised as symptoms of mental illness. The study highlighted the need for strategies that can educate, influence and mobilise communities in south-east Nigeria concerning the aetiology, prevention, early detection and treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms within the first 9 months of onset of illness.

Conclusion

In the present study, patients with PNS were associated with a longer DUP, which could be a result of wrong interpretation of symptoms. This study brings to the fore the place of community psychiatry in effective service delivery and reduction in DUP, through the use of intensive information campaigns on mental illness.

References

1. Wright P. Schizophrenia and related disorders. In: Wright P, Stern T, Phelan N, eds. Core Psychiatry. London: WB Saunders, 2000:259-292. [ Links ]

2. Mueser KT, McGurk SR. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2004;363(9426):2063-2072. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16458-1] [ Links ]

3. Kendel RE, Zeally AK. Schizophrenia. Companion to Psychiatric Studies. 5th ed. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone, 1993:397-426. [ Links ]

4. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, et al. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: A systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62(9):975-983. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975] [ Links ]

5. Dell'Osso B, Altamura AC. Duration of untreated psychosis and duration of untreated illness: New vistas. CNS Spectr 2012;15(4):238-246. [ Links ]

6. Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;18:CD004718. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub3] [ Links ]

7. Lincoln CV, McGorry PD. Pathways to care in early psychosis: Clinical and consumer perspectives. In: McGorry P, Jackson HJ, eds. The Recognition and Management of Early Psychosis: A Preventive Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [ Links ]

8. Abiodun OA. Pathways to mental health care in Nigeria. Psychiatr Serv 1995;46(8):823-826. [ Links ]

9. McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO. Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: Rationale. Schizophr Bull 1996;22(2):201-222. [ Links ]

10. Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatr Suppl 1998;172(33):53-59. [ Links ]

11. Sauter SL, Murphy LR, Hurrell JJ. Prevention of work-related psychological disorders: A national strategy proposed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Am Psychol 1999;45(10):1146-1158. [ Links ]

12. Pote HL, Orrell MW. Perceptions of schizophrenia in multi-cultural Britain. Ethn Health 2007;7(1):7-20. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13557850220146966] [ Links ]

13. Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al. Prevention of negative symptom psychopathologies in first-episode schizophrenia: Two-year effects of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65(6):634-640. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.634] [ Links ]

14. Burns JK, Jhazbhay K, Emsley RA. Causal attributions, pathway to care and clinical features of first-episode psychosis: A South African perspective. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2001;57(5):538-545. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0020764010390199] [ Links ]

15. Erritty P, Wydell TN. Are lay people good at recognising the symptoms of schizophrenia? PLoS ONE 2013;1:e52913. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone] [ Links ]

16. Mkize LP, Uys LR. Pathways to mental health care in KwaZulu-Natal. Curationis 2004;27(3):62-71. [ Links ]

17. Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Hutchinson J, et al. Pathways to care: Help seeking behaviour in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;106(5):358-364. [ Links ]

18. Boonstra N, Klaassen R, Sytema S, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and negative symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Schizophr Res 2012;142(1-3):12-19. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.017] [ Links ]

19. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 2006;32(2):214-219. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj053] [ Links ]

20. Buckley PF, Stahl SM. Pharmacological treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia: Therapeutic opportunity or cul-de-sac? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;115(2):93-100. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00992.x] [ Links ]

21. Leucht S, Heres S, Kissling W, Davis JM. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;14(2):269-284. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1461145710001380] [ Links ]

22. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Schizophrenia: The NICE Guideline on Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizoprenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. Updated edition. London: British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2010. [ Links ]

23. Castelein S, Bruggeman R, Van Busschbach JT, et al. The effectiveness of peer support groups in psychosis: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008;118(1):64-72. [ Links ]

24. Gold C, Solli HP, Kruger V, Lie SA. Dose-response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29(3):193-207. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.001] [ Links ]

25. RÖhricht F, Priebe S. Effect of body-oriented psychological therapy on negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2006;36(5):669-678. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706007161] [ Links ]

26. Steel Z, McDonald R, Silove D, et al. Pathways to the first contact with specialist mental health care. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40(4):347-354. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01801.x] [ Links ]

27. Central Intelligence Agency. Calculation from percentage and overall population count of Nigeria. In: CIA The World Factbook. Virginia, USA: Directorate of Intelligence, 2012. [ Links ]

28. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders-Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. [ Links ]

29. Gater R, de Almeida e Sousa B, Barrientos G, et al. The pathways to psychiatric care: A cross-cultural study. Psychol Med 1991;21(3):761-774. [ Links ]

30. Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, et al. Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:1183-1188. [ Links ]

31. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 1987;13:261-276. [ Links ]

32. Wittchen HU, Pfister H. DIA-X-Interviews: Manual für Screening-Verfahren und Interview; Interviewheft Längsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Er-gänzungsheft (DIA-X-Lifetime); Interviewheft Querschnittsuntersuchung (DIA-X-12. Monats-Version); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-12. Monats-Version); PC-Programm zur Durchführung der Interviews (Längsund Querschnittsuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. Frankfurt: Swets & Zeitlinger, 1997. [ Links ]

33. Village A. Dimensions of belief about miraculous healing. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 2005;8(2):97-107. [ Links ]

34. World Health Organization. Fact Sheet No. 134: Traditional Medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [ Links ]

35. Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, et al. Pathways to care and ethnicity. In: Sample Characteristics and Compulsory Admission. Report from the AESOP Study. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:281-289. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.4.281] [ Links ]

36. Norman RM, Malla AK. Duration of untreated psychosis: A critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med 2001;31(3):381-400. [ Links ]

37. Larsen TK, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S. First-episode schizophrenia with long duration of untreated psychosis: Pathways to care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998;172(33):45-52. [ Links ]

38. McGlashan TH. Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: Marker or determinant of course? Biol Psychiatry 1999;46(7):899-907. [ Links ]

39. Rhi BY, Ha KS, Kim YS, et al. The health care seeking behaviour of schizophrenic patients in 6 east asian areas. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1995;41(3):190-209. [ Links ]

40. Winkler AS, Mayer M, Ombay M, Mathias B, Schmutzhard E, Jilek-Aall L. Attitudes towards African traditional medicine and Christian spiritual healing regarding treatment of epilepsy in a rural community of northern Tanzania. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2010;7(2):162-170. [ Links ]

41. Elujoba AA, Odeleye OM, Ogunyemi CM. Traditional medical development for medical and dental primary health care delivery system in Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2005;2(1):46-61. [ Links ]

42. Adogame A. HIV/AIDS support and African Pentecostalism: The case of the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG). J Health Psychol 2007;12(3):475-484. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105307076234] [ Links ]

43. Obisesan KA, Adeyemo AA. Infertility and other fertility related issues in the practice of traditional healers and Christian religious healers in south western Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 1998;27(1-2):51-55. [ Links ]

44. Teuton J, Dowrick C, Bentall RP. How healers manage the pluralistic healing context: The perspective of indigenous, religious and allopathic healers in relation to psychosis in Uganda. Soc Sci Med 2007;65(6):1260-1273. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.055] [ Links ]

45. Wanyama J, Castelnuovo B, Wandera B, et al. Belief in divine healing can be a barrier to antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. AIDS 2007;21(11):1486-1487. [ Links ]

46. Singh SP, Grange T. Measuring pathways to care in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review. Schizophr Res 2006;81(1):75-82. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.018] [ Links ]

47. Srinivasan TN, Rajkumar S, Padmavathi R. Initiating care for untreated schizophrenia patients and results of one year follow-up. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2001;47(2):73-80. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002076400104700207] [ Links ]

48. O'Callaghan E, Turner N, Renwick L, et al. First episode psychosis and the trail to secondary care: Help-seeking and health-system delays. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45(3):381-91. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0081-x] [ Links ]

49. Lincoln CV, Harrigan S, McGorry PD. Understanding the topography of the early psychosis pathways: An opportunity to reduce delays in treatment. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998;172(33):21-25. [ Links ]

50. Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B, et al. The key to reducing duration of untreated first psychosis: Information campaigns. Schizophr Bull 2008;34(3):466-472. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm095] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

P C Odinka (paul.odinka@unn.edu.ng)