Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Psychiatry

versão On-line ISSN 2078-6786

versão impressa ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.20 no.4 Pretoria Out./Dez. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajp.619

ARTICLE

Does religious identification of South African psychiatrists matter in their approach to religious matters in clinical practice ?

M A WelgemoedI; C W van StadenII

IMB ChB; Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria; and Weskoppies Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

IIMB ChB, MMed (Psych), MD, FCPsych (SA), FTCL, UPLM; Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria; and Weskoppies Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: It is not known whether psychiatrists' approach to religious matters in clinical practice reflects their own identification or non-identification with religion or their being active in religious activities.

OBJECTIVE: This question was investigated among South African (SA) psychiatrists and psychiatry registrars, including the importance they attach to the religious beliefs of patients for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

METHODS: Respondents from the SA Society of Psychiatrists (SASOP) completed a purpose-designed questionnaire anonymously online. Respondents were compared statistically with regard to whether they identified with a religion, and the regularity of their participation in religious activities. Further comparisons were made based on gender and years of clinical experience.

RESULTS: Participants who identified with a religion showed no statistical differences in comparison with those who did not, regarding: how they viewed the importance of a patient's religious beliefs for purposes of diagnosis, general management, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, recovery from an acute episode, maintenance of recovery or remission, time to be spent on religious education, referral for religious/spiritual counselling according to patient's own beliefs; referral when patient and participant are of different religions; and whether referral is considered harmful when a patient's religious beliefs are similar to or different from the participant's. Statistically significant differences were found where participants who did not identify with a religion were more likely to indicate religion had 'little importance' for the purpose of understanding the patient and to indicate 'no' when asked if they would refer a patient for religious/spiritual counselling. When comparing regularity of participation in religious gatherings, participants who indicated their participation as 'no/never' were more likely to answer 'no' when asked if they would refer a patient for religious/spiritual counselling, even when of a similar religion to that of their patient. In comparing genders, males were more likely to answer 'yes' than females when asked if they considered religious/spiritual counselling (in accordance with the patient's own religious beliefs) potentially harmful when the patient's religion was different from the participant's.

CONCLUSION: It appears that SA psychiatrists' identification with religion and regularity of participation in religious gatherings do not influence their approach to religious matters of their patients in most respects. The exception seems to be for those psychiatrists who do not identify with a religion (~16%), who tend to respond that they do not refer for religious counselling and that they consider the patient's religious identification to be of little importance in understanding the patient.

Religion and psychiatry have been described metaphorically as occupying, at least in part, the same country - a landscape of meaning, significance, guilt, belief, values, vision, suffering and healing.[1] Amid a growing body of literature on this shared territory, various studies consistently suggest that patients would like practitioners to address the religious aspects of their lives.[2,3]

Previous studies have indicated that more religious involvement is usually associated with better mental health, but it is also clear that, at times, religion can be used negatively and can be incorporated into a patient's psychopathology.[4-6] As an example of the impact - positive or negative - that religious beliefs may have, one may consider their role in adherence to treatment and follow-up for further psychiatric care. While the reasons for non-adherence are heterogeneous, including poor infrastructure and logistical problems, lack of information about the patient's condition and medication, potential side-effects of medication and poor relationships with healthcare providers, they also include religious beliefs of patients and families about mental health, psychiatric conditions and treatments. [7] For psychiatrists to understand religious matters in a person's life requires skill and knowledge by which pathological and non-pathological religious aspects may be differentiated.

Clinicians involved in psychiatric care would have noticed that for some patients with mental disorders, religion/spirituality also represents an important way of making sense of and coping with the demands of the illness. The biopsychosocial model of care underscores the need to consider patients from a holistic perspective, thus avoiding a reductionistic view that considers only biological or psychological aspects of the person. This model may include religion/spirituality in its social designation, or one may account for religion/spirituality in a biopsychosocial-religious/spiritual model.[8]

Clinicians providing psychiatric services may have many reasons for avoiding patients' spiritual/religious issues. The clinician's own religious involvement may influence the value they place on religious/spiritual issues, e.g. there may be a lack of knowledge about how to address religion or spirituality in clinical practice, and clinicians may fear that addressing issues pertaining to religion may represent walking into unknown territories, thus risking harm to patients. Medical treatment may even enter into conflict with the teachings of religious groups.[8] Curlin et al. [9] found that psychiatrists are more likely than physicians and other specialists (82% v. 44%) to note that religion or spirituality sometimes causes negative emotions, perhaps because they are also more likely (92% v. 74%) to encounter religious or spiritual issues in the clinical setting.[9]

Understanding the patient's religion may help to improve therapeutic efficacy and also help the psychiatrist to assist the patient in managing possible negative aspects. [1] Doing so raises the question regarding the influence of psychiatrists' own religious beliefs, including the lack thereof, on the way they approach the religion of their patients in practice. A Canadian study found that a psychiatrist's own beliefs and practices were strong predictors of his or her willingness to enquire about their patient's religion or spirituality.[10] Another study found that psychiatrists refer patients to chaplains less frequently than to other professionals and are more likely to refer patients to psychoanalytic and hospital outpatient settings.[11]

As the importance of spirituality in mental health and psychiatry seems to feature more prominently, it would be prudent that local South African (SA) psychiatrists consider from within the discipline the place that spirituality should be given in specialist psychiatric practice and education.[12,13] According to the views of psychiatrists expressed in a recent qualitative study in SA, spirituality should be incorporated into the current biopsychosocial approach irrespective of one's own stance on spirituality and religion. [13] Building on the affordance of this qualitative study, our quantitative study sought data by which some of those findings could be generalised. More specifically, it enquired on the self-identification of SA psychiatrists with religion and whether that identification influences the way in which they approach the religion of their patients during clinical interaction. Findings of this enquiry, within its limitations, should help to inform and support the objectives stated in the position statement of the SA Society of Psychiatrists (SASOP).[12]

Methods

In this quantitative study, a cross-sectional survey was designed to compare psychiatrists with respect to their self-expressed clinical approach to religious matters of their patients, depending on whether they self-identified as being religious or not, how often they participated in the usual gatherings of their religion, their gender and their number of years of clinical experience.

Eligible participants were psychiatrists and registrars in psychiatry practising in SA. They were invited to participate by e-mail requests that had been sent to all members and associates listed in the SASOP database during 2012. Data were obtained by means of an online questionnaire that was hosted on SASOP's website for a period of 6 months. The size of the population of psychiatrists and registrars in psychiatry was ~600 at the time. A total of 136 participants completed and submitted the questionnaire. Data were collected anonymously and in electronic format. Statistical testing used the application of Fisher's exact test on cross-tabulations.

A questionnaire was designed for the purpose of this study (available on request), and comprised 19 questions drawn up by means of an iterative process among the researchers and in consultation with an expert on religion in psychiatry. In summary, the items enquired about: age; gender; years of clinical experience; religious identification; regularity of participation in religious gatherings; the importance of patients' beliefs for purposes of understanding, diagnosing, general management, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, recovery and remission; amount of time to be allocated for religious training; and referral considerations and patterns.

The study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria. Participant confidentiality was ensured by means of the participants completing the questionnaire anonymously. Informed consent was obtained by including a written description about the research at the beginning of the questionnaire and a statement indicating that the completion and the submission of the questionnaire affirmed informed consent by the participant, which could not be withdrawn once the questionnaire had been submitted.

Results

There were 136 respondents, of whom 115 (84%) self-identified with a religion. There were 30 respondents who indicated their regularity of participation in religious gatherings as 'no/never', which is more than the 22 who did not identify with a religion. Regularity of participation was indicated by 52 respondents (38%) as 'hardly ever/once per month', and by 53 (39%) as 'once/twice per week'. The gender of respondents was indicated by 58 as male and 77 as female. Regarding years of experience in psychiatry, 50 respondents (37%) had <11 years' work experience, 47 (34%) had 11 - 20 years, 32 (23%) had 21 - 30 years, and 8 (6%) had more than 30 years' experience.

Self- identification with religion

A total of 84% of participants (n=115) self-identified with a religion and 16% (n=22) opted for 'no religious identification', with statistically a highly significant difference (p=0.0001).

Table 1 presents the number of participants who responded to questions regarding how they viewed the importance of their patients' religious beliefs in clinical practice for purposes of understanding the patient, and in the diagnosis, general management, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, recovery from an acute episode, and maintenance of recovery or remission.

Most striking was that participants who did not identify with a religion were statistically more likely to indicate 'little importance' with respect to the importance of the patient's beliefs in understanding the patient (Fisher's exact test = 10.280; p=0.010). No other statistically significant results were found for the values in Table 1.

Referral patterns were examined by asking respondents to imagine consulting for a patient who usually participates in his/her religious activities, has a stable axis 1 diagnosis, but is currently in the process of a normal bereavement. Respondents were asked whether they would usually refer such a patient for religious/spiritual counselling in accordance with the patient's religious beliefs. Table 2 presents these results by the religious identification of respondents as well as responses to the following: whether they would usually refer such a patient for religious/spiritual counselling when participant and patient were of a similar or different religion from their own; whether by virtue of their being religious or not, they would refrain from referring such a patient for religious/spiritual counselling when their religion was different from the patient's; and whether they would consider it potentially harmful to refer such a patient for religious/spiritual counselling when the patient was from a similar or different religion from their own.

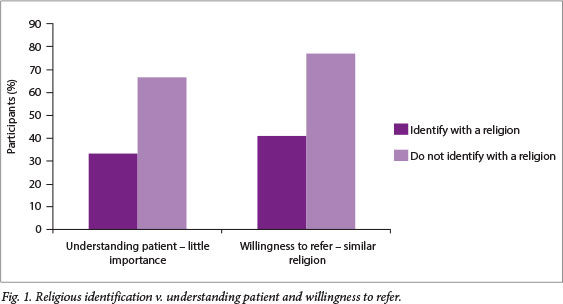

Most striking was that participants who did not identify with a religion were more likely to answer 'no' when asked if they would usually refer such a patient for religious/spiritual counselling (Fig. 1), (χ2=9.62; p=0.002). No statistically significant differences were found for the other items.

Regularity of participation in religious gatherings

Since identification with a religion does not necessarily mean that the respondent practices religion actively, regularity of participation in religious gatherings was also examined in relation to the importance that the respondents ascribed to patients' religious beliefs in clinical practice. The number of participants who responded to the questions (same set of questions as indicated above) was examined for three groups based on the regularity of their participation in religious gatherings (Table 3). Mostly no statistical significant differences were found.

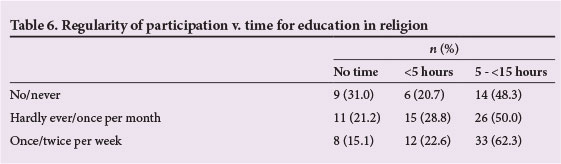

Regarding referral, Table 4 presents the data for the groups based on regularity of participation in religious gatherings. Participants who indicated their regularity of participation in religious gatherings as 'no/never' were less likely to refer patients for religious/spiritual counselling when the patient was from a similar religion to the participant's (70% indicated 'no' while the other two groups indicated 'no' at 45% and 36%, respectively) (Fisher's exact test = 9.04; p=0.01).

Gender

The same set of questions (Tables 1 and 2) was compared between two groups based on gender. One statistically significant difference was found for the question on whether the participant would consider referral for religious/spiritual counselling potentially harmful when the patient was of a religion different from the participant's. To this question, 23 males and 10 females indicated 'yes', and 34 males and 66 females indicated 'no'. This means that males were more likely to answer 'yes' than females (χ2=12.9; p<0.01).

Years of clinical experience

The same set of questions (Tables 1 and 2) was compared between four groups based on years of clinical experience (0 - 10; 11 - 20; 21 - 30; >30), and no statistically significant differences were found.

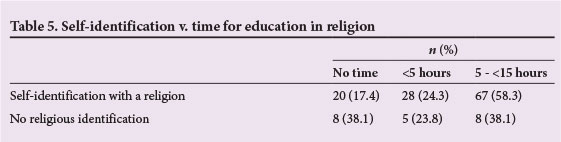

Time for education in religion

Participants indicated their view regarding the length of time that should be spent on education in religion during the 4-year training period for registrars in psychiatry. No statistically significant differences were found in any of the comparisons (Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

A study that was done in London teaching hospitals found that 27% of psychiatrists working in these hospitals reported religious affiliation, and 23% a belief in God.[14] Our study revealed a strikingly different situation in SA, where 83.9% of the participants self-identified with a religion.

Whether psychiatrists and registrars in psychiatry identified with a certain religion or not, for the majority of aspects this did not influence their reported approach to religious matters in the clinical setting. There were nonetheless certain aspects for which significant statistical differences were identified. Statistically significant differences were found for participants who did not identify with a religion, who were more likely to indicate that religion had 'little importance' in understanding the patient, and who were more likely to indicate 'no' when asked if they would refer a patient for religious/spiritual counselling. When comparing responses in relation to regularity of participation in religious activities, participants who indicated their level of participation as 'no/never' were more likely to answer 'no' when asked if they would refer patients for religious/spiritual counselling. In comparing gender, males were more likely to answer 'yes' than females when asked if they considered religious/spiritual counselling in accordance with the patient's own religious beliefs potentially harmful, but only when the patient's religion was different from the participant's.

How psychiatrists view and approach religious matters in the clinical setting is important for patients, with various studies consistently suggesting that patients would like practitioners to address this area of their lives.[2,3]The finding of this study was that in most religious/spiritual aspects, other than the ones mentioned above, clinical practice was not affected by the religious identification of psychiatrists and registrars. This may serve as some comfort to patients in sharing the significance of religious matters with their psychiatrist.

A Canadian study found that the psychiatrist's own beliefs and practices were, however, strong predictors of his/her willingness to enquire about their patient's religion/spirituality,[10] while another study found no evidence to support this.[14] Our study does not support the findings of the Canadian study; our findings rather seem to defy them.

The literature provides considerable evidence that indicates the positive effect and benefit of religious belief in achieving good mental health, as well as recovery from mental illness. For this reason, it is important for psychiatrists/registrars to be aware of and to understand a patient's religious experience and aspirations. Because both religion and psychiatry share key values concerning respect for individuals, a greater degree of co-operation should be strived for.[1] Our study indicated a predominantly willing attitude of psychiatrists/registrars to responsibly liaise and co-operate with the various key role players of the patient's religious or spiritual identification/group.

It is a necessary skill to be able to differentiate between pathological and non-pathological religious involvement. For psychiatric residents, spirituality as a potential source of higher functioning for the patient must be included in training programmes.[7] The findings of our study suggested support for this. When comparisons were made between the religious and non-religious groups, there was no significant difference in opinion regarding the amount of time that should be spent on education in religion during the 4-year training period of registrars in psychiatry in preparation for specialist practice (the average suggestion was 'more than 5 hours'). This would seem to suggest an awareness of the need for religious/spiritual education as part of psychiatry training.

The way in which the data were collected in this study, i.e. the sampling method, can be regarded as a study limitation, as psychiatrists/registrars who took part in the study might have had a greater interest in religious/spiritual matters than psychiatrists/registrars who did not take part. The sampling was also influenced by the willingness of psychiatrists to respond. Thus the findings should not be generalised to those who are not inclined to participate in such a survey, or outside of the SA context. The findings of this study, furthermore, are not static, but may change over time.

The benefit of this study lies in its potential to improve holistic patient care by creating an awareness of various influences affecting religious matters in clinical practice. The impact of the study may be that psychiatrists/registrars (re)consider their own position when dealing with the religious matters of their patients during clinical interaction. The study also informs us on the perceived need for education in religion during psychiatric training, as expressed by 72% of our respondents.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to Prof. Bernard Janse van Rensburg for his professional advice and guidance. We would also like to thank Mr A Swanepoel and Mrs J Jordaan from the Department of Statistics at the University of Pretoria for their assistance and guidance.

References

1. Sims A. The cure of souls: Psychiatric dilemmas. Int Rev Psy,chiatry 1999;11(2-3):97-102. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540269974249] [ Links ]

2. King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract 1994;39(4):349-352. [ Links ]

3. Ellis M, Vinson DC, Ewigman B. Addressing spiritual concerns of patients: Family physicians' attitudes and practice. J Fam Pract 1999; 48(2):105-109. [ Links ]

4. Levin JS, Chatters LM. Research on religion and mental health: An overview of empirical findings and theoretical issues. In: Koening HG, ed. Handbook of Religion and Mental Health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998:33-50. [ Links ]

5. McCulloygh ME, Larson DB. Religion and depression: A review of the literature. Twin Res 1999;2(2):126-136. [ Links ]

6. Koening HG, McCulloygh ME, Larson DB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001:60-77. [ Links ]

7. Janse van Rensburg ABR, Myburgh CPH, Szabo CP, Poggenpoel M. The role of spirituality in specialist psychiatry: A review of the medical literature. Afr J Psychiatry 2013;16(4):247-255. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v16i4.33] [ Links ]

8. Huguelet P, Koenig HG. Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

9. Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Odell S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Psychiatrists' and other physicians' differing observations, interpretations, and clinical approaches. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164(12):1825-1831. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122088] [ Links ]

10. Baetz M, Griffin R, Bowen R, Marcoux G. Spirituality and psychiatry in Canada: Psychiatric practice compared with patient expectations. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49(4): 265-271. [ Links ]

11. Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE, et al. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among US physicians. Psychiatry Serv 2007;58(9):1193-1198. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.58.9.1193] [ Links ]

12. Janse van Rensburg ABR. The South African Society of Psychiatrists (SASOP) and SASOP State Employed Special Interest Group (SESIG) position statements on psychiatric care in the public sector. S Afr J Psychiatr 2012;18:133-148. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJP.374] [ Links ]

13. Janse van Rensburg ABR, Poggenpoel M, Myburgh CPH, Szabo CP. Experience and views of academic psychiatrists on the role of spirituality in South African specialist psychiatry. Rev Psiq Clín 2012;39(4):122-129. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832012000400002] [ Links ]

14. Neeleman J, King MB. Psychiatrists' religious attitudes in relation to their clinical practice: A survey of 231 psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993;88(6):420-424. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M A Welgemoed (mariuswelgemoed@gmail.com)