Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Psychiatry

versão On-line ISSN 2078-6786

versão impressa ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.20 no.3 Pretoria Jul./Set. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJP.498

ARTICLE

DOI:10.7196/SAJP.498

Where there is no psychiatrist: A mental health programme in Sierra Leone

P AlonsoI, II; B PriceIII; A R ContehIV; C ValleV; P E TurayVI; L PatonVII; J A TurayV

IPhD; Department of Psychiatry, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute-IDIBELL, Hospital de Bellvitge, University of Barcelona, Spain

IIPhD;Centro de Investigación en Red de Salud Mental, Carlos III Health Institute, Madrid, Spain

IIIPhD; Adler School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, Illinois, USA

IVBN; Holy Spirit Hospital, Makeni, Sierra Leone

VPhD; University of Makeni, Sierra Leone

VIMD; Holy Spirit Hospital, Makeni, Sierra Leone

VIIPsyD; University of Makeni, Sierra Leone

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: For most low- and middle-income countries, mental health remains a neglected area, despite the recognised burden associated with neuropsychiatric conditions and the inextricable link to other public health priorities.

OBJECTIVES: To describe the results of a free outpatient mental health programme delivered by non-specialist health workers in Makeni, Sierra Leone between July 2008 and May 2012.

METHODS: A nurse and two counsellors completed an 8-week training course focused on the identification and management of seven priority conditions: psychosis, bipolar disorder, depression, mental disorders due to medical conditions, developmental and behavioural disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and dementia. The World Health Organization recommendations on basic mental healthcare packages were followed to establish treatment for each condition.

RESULTS: A total of 549 patients was assessed and diagnosed as suffering from psychotic disorders (n=295, 53.7%), manic episodes (n=69, 12.5%), depressive episodes (n=53, 9.6%), drug use disorders (n=182, 33.1%), dementia (n=30, 5.4%), mental disorders due to medical conditions (n=39, 7.1%), and developmental disorders (n=46, 8.3%). Of these, 417 patients received pharmacological therapy and 70.7% were rated as much or very much improved. Of those who could not be offered medication, 93.4% dropped out of the programme after the first visit.

CONCLUSIONS: The identification and treatment of mental disorders must be considered an urgent public health priority in low- and middle-income countries. Trained primary health workers can deliver safe and effective treatment for mental disorders as a feasible alternative to ease the scarcity of mental health specialists in developing countries.

Mental disorders are an important cause of long-term disability and dependency, with the 2005 World Health Organization (WHO) report attributing 31.7% of all years lived with disability to neuropsychiatric conditions,[1] particularly unipolar depression (11.8%), alcohol-use disorder (3.3%), schizophrenia (2.8%), bipolar depression (2.4%) and dementia (1.6%). This significant burden affects both more-developed countries and those that are poorer and less well resourced. However, mental health remains a low priority in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which tend to prioritise the control and eradication of infectious diseases, and reproductive, maternal and child health.[2] Investment in mental health is often perceived in these countries as having an unaffordable opportunity cost. As a result, there is an large treatment gap for people with neuropsychiatric disorders in LMICs. While at least two-thirds of all persons with mental illnesses go untreated worldwide, the figure for low-resource countries exceeds 90%.[3]

There is also a conspicuous lack of published literature evaluating the implementation of mental healthcare programmes in low-income countries. Fewer than 1% of identified trials worldwide that aimed to treat or prevent schizophrenia, depression, developmental disabilities or alcohol-use disorder were conducted in low-income countries, and of these about two-thirds come from China.[4] In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, the vast majority of published data from mental health research (nearly 70%) is focused on South Africa,[5] an emerging country that is not representative of the region as a whole. Sierra Leone, in the sub-Saharan area, occupies one of the lowest positions in the Human Development Index drawn up in 2008,[6] ranked 128th among 135 countries for which a Human Poverty Index was calculated. The proportion of its population below the poverty line of US$1.25 per day is estimated at 47.7%. The country has recently emerged from a brutal, decade-long civil war during which civilians were victims of widespread violence, including amputation of body parts, rape and forced labour. After this devastating conflict, the health system, like all public systems, was in tatters. Nevertheless, the country has managed to implement a free healthcare plan for pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers and children younger than 5 years, that has been proposed as an example for LMICs.[7] As countries such as Sierra Leone continue to rebuild after conflicts, the need to develop services for all from the ground up may offer a unique window of opportunity for the inclusion of persons suffering from mental disorders into the health system.

Reports on mental health initiatives in LMICs are crucial to provide more direct evidence regarding cost-effective interventions that may help low-income countries use their limited financial and human resources for mental health as effectively as possible. This article describes the results of a free outpatient mental health programme that was run in Makeni (Sierra Leone) between July 2008 and May 2012. The programme was delivered by trained non-specialist health workers integrated into the existing healthcare system.

Methods

Setting

Since 2011, there has not been a single psychiatrist in Sierra Leone; only occasionally is there input from foreign professionals via NGOs. The country has only one facility for treating mental health patients on a long-term basis using Western medicine, namely the Kissy Mental Hospital in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. Makeni, located approximately 137 km east of Freetown, is the 5th largest city in Sierra Leone and is the economic centre of the Northern Province. It has a current estimated population of 109 112 and is the capital of the Bombali District, of which the estimated population is 439 319.

The Holy Spirit Hospital is linked to the University of Makeni, and both form part of the Catholic Diocese of Makeni. The hospital has a 70-bed admission ward and treats 300 inpatients and 1 200 outpatients per month. It has 3 general doctors and 50 nurses and support staff.

Programme description

The mental health programme was initiated in July 2008 as a free outpatient programme open to patients from Makeni and its surrounding district. The programme staff comprised a nurse and two counsellors, who underwent an 8-week training course run by a volunteer psychiatrist, focusing on the identification and management of mental disorders. The course was specifically designed for the programme by a volunteer Italian psychiatrist, Dr Lorenzo Tamale, who has extensive clinical experience in fellowship training in psychiatry, as part of a larger collaboration project with the University of Makeni to develop a Public Health Studies programme. Dr Edward Nahim, the only psychiatrist in Sierra Leone at that time, who was in charge of the Kissy Mental Hospital in Freetown, and Dr Patrick Turay, Medical Director of the Holy Spirit Hospital, also contributed to the design of the programme. Seven priority conditions were considered: depression, psychosis, bipolar disorder, mental disorders due to medical conditions (mainly epilepsy, stroke and brain injury), developmental and behavioural disorders in children and adolescents, alcohol and drug use disorders, and dementia. These areas were chosen because they represent a considerable burden in terms of mortality, morbidity or disability, have high economic costs and are often associated with violations of human rights.[8,9] Patel et al.[8] and the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) published by the WHO in 2010[9] both recommend the use of similar global diagnostic classes in order to increase the validity of the diagnostic process, since non-specialist health workers generally find it easier to differentiate between these major classes of disorders (e.g. schizophrenic disorders v. affective disorders) than within classes of disorders (e.g. schizophrenic disorders v. schizoaffective disorders); the latter would, of course, allow the use of more complicated diagnostic classifications such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (text revised) or International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision. The training course followed a stepwise design. First, the staff were instructed to take a complete medical history of the patient and to evaluate relevant information on medical and mental family history. Then, they were trained to assess common presentations of the seven priority conditions after being provided with a summarised, straightforward clinical description of each one. Direct supervision of clinical interviews, psychopathological assessment and diagnostic processes was provided during the training course, as well as critical support on management of and interventions in each condition.

The WHO recommendations[10] on basic mental healthcare packages were followed in order to establish treatment for each diagnostic condition, namely: outpatient-based treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with first-generation antipsychotic drugs and adjuvant psychosocial treatment; and proactive care of depression with generic, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants and maintenance treatment of recurrent episodes. Mood-stabilising drugs such as lithium or valproate were not administered for bipolar disorders due to the lack of laboratory facilities for monitoring the blood levels of these drugs. Anticholinergic agents were not routinely prescribed but were given to those patients who developed extrapyramidal side-effects. Patients were asked to attend the programme accompanied by a family member, who was responsible for medication administration. Pharmacological treatment was provided solely by the nurse for an initial period of 3 days, after which the patient was asked to recontact the programme. If no severe adverse effect was detected, medication was provided for a maximum period of 1 month. All patients were asked to contact the programme for follow-up assessment at least monthly. Brief psychological interventions, based on motivational techniques for alcohol and other drug use disorders, and mental illness psycho-education, promotion of treatment adherence, and support to families and caregivers for other conditions, were offered by the two counsellors.

The cost of the programme was borne by (i) CAFOD (Catholic Agency For Overseas Development), which provided medication and covered the salary of the counsellors, and (ii) the Holy Spirit Hospital/ University of Makeni, which paid the nurse's salary and provided a hospital annex area from which the programme could be run.

Data collection

A questionnaire was developed to facilitate the assessment of patients (available from the authors on request), which covered sociodemographic information (age, gender, completed years of education, marital status and employment), service utilisation (previous contact with primary healthcare providers, traditional healers and hospital services, and medication use), and clinical information (alcohol and drug consumption, family psychiatric history, age at onset of psychiatric symptoms and psychopathological assessment). All patients were initially assessed by the nurse and then independently reassessed by one of the counsellors. Any differences in diagnostic opinion were discussed by the programme team until a consensus was reached.

Clinical changes were evaluated with the Clinical Global Impression - Improvement (CGI-I) Scale,[11] which assesses how much a patient's illness has changed relative to baseline. The patient's status is rated as: very much improved (1); much improved (2); minimally improved (3); no change (4); minimally worse (5); much worse (6); or very much worse (7).

Direct supervision on diagnoses and treatment procedures was provided for 4 weeks per year by different volunteer psychiatrists and psychologists from the University of Barcelona (Spain) and the Adler School of Professional Psychology (USA), among other institutions. Training material from the mhGAP Intervention Guide, available from 2010 onwards, was used to improve the diagnosis and management processes. All case records obtained during the previous year were examined in order to ensure optimal data collection, as well as to supervise diagnoses. Informed consent was not available due to the characteristics of the environment, but all patients attended the programme voluntarily. Rev Fr Joseph A Turay, Deputy Vice Chancellor of the University of Makeni, and Dr Patrick Turay, Medical Director of the Holy Spirit Hospital, gave permission for the implementation and development of the programme. The Institutional Review Board of the Adler School of Professional Psychology evaluated the project and approved the analysis of data and presentation of results. All analyses were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008).

Data analysis

A database in which patients' anonymity was ensured was built between July 2011 and May 2012 by reviewing all available records. Descriptive statistics were applied to the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Gender differences and differences between diagnostic conditions were explored using χ2 tests for categorical variables and independent sample t-tests for continuous variables. These analyses were performed with SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., USA) and significance thresholds were set at p<0.05, two-tailed.

Results

Description of patients' characteristics

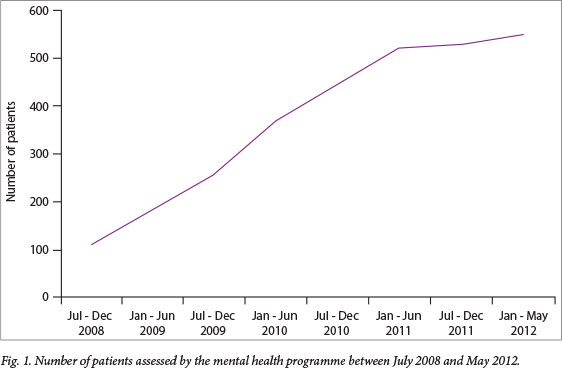

A total of 549 patients (327 males and 227 females) was assessed between July 2008 and May 2012 (Fig. 1). Men were significantly younger, tended to be single, reported a higher mean educational level, and were more likely to have a history of nicotine, alcohol or cannabis abuse/dependence. Agitation and hallucinations were more common among men than women, whereas the latter reported more affective symptoms (from both the depressive and manic poles), loss of appetite and a positive family psychiatric history (Table 1).

The main psychiatric symptoms reported were: agitation (76.8%); disorganised behaviour (74.4%); insomnia (70.8%); hetero-aggressive behaviour (69.2%); hallucinations (52.0%); delusions (38.2%); loss of appetite (25.5%); depressive mood (15.8%), which included low mood, hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, loss of energy, and loss of interest in pleasurable activities; manic mood (12.5%), including elevated or irritable mood, expanded self-esteem, pressured speech, reduced need for sleep, increased distractibility, racing thoughts and hyperactivity; and cognitive dysfunctions (10.0%), including disorientation, memory loss, difficulties with judgement, reasoning and understanding, and impaired organisational and language skills. Self-aggressive behaviour, including suicide attempts and self-injurious behaviour, was present in ten patients (1.8%).

The main psychiatric diagnoses were psychotic disorders (n=295, 53.7%), manic episodes (n=69, 12.5%), depressive episodes (n=53, 9.6%), substance use disorders (n=182, 33.1%), dementia (n=30, 5.4%), mental disorders due to medical conditions (n=39, 7.1%), and developmental disorders (n=46, 8.3%). Sociodemographic and clinical differences between diagnoses are described in Table 2. While psychotic and substance use disorders were significantly more common among men, women presented significantly higher rates of affective episodes (manic and depressive) and dementia. Of the patients, 389 (70.8%) reported having visited a traditional healer before contacting the mental health programme. The percentage was significantly higher among women (77.1% v. 66.5% in men) (χ2=8.2, p<0.01). Regarding referral networks, 124 patients were referred to the mental health programme by their family doctor (22.7%), while the remainder asked for help under their own initiative after having heard about the mental health programme through other members of their communities.

Description of prescription patterns

Pharmacological treatment was recommended in accordance with WHO criteria and, when available, was provided free to all patients (see Table 3 for specific drug prescriptions). Pharmacological treatment was provided by the nurse under the direct supervision of the medical director of the hospital. A total of 417 patients received pharmacological therapy, while in 123 cases medication was prescribed but not available because of medication supply issues in the programme. In nine cases, pharmacological treatment was not considered necessary and some kind of counselling was implemented.

Patients receiving pharmacological treatment attended the programme for a mean (SD) 6.0 (8.2) (range 0 - 42) months; those who were not offered medication the mean period of adherence to the programme was 0.1 (0.8) months (t=-8.1, p<0.001). Of the patients receiving pharmacological treatment, 70 (16.7%) dropped out of the programme after the first visit, while the corresponding figure for those who could not be offered medication was 115 of 123 (93.4%) (χ2=245.04, p<0.001). A total of 295 of the 417 patients receiving medication (70.7%) was rated as much or very much improved, whereas no patients achieved these ratings in the group not receiving medication.

Discussion

This is the first study of a mental health programme designed and implemented in one of the world's poorest countries, Sierra Leone, where not a single psychiatrist is available. Our results add to the emerging body of evidence showing that trained primary health workers can deliver safe and effective treatment for mental disorders by using low-cost pharmacological strategies and brief psychological interventions within a functioning primary healthcare system.[12]

Most of the patients who were seen in the programme presented with severe mental disorders (psychotic disorders, manic episodes, severe depressive episodes), with the main reason for attending being behavioural disturbances (such as psychomotor agitation, or heteroaggressive or disorganised behaviour) that were having a significant impact on their environment. This is consistent with a previous report by Gesler and Nahim[13] concerning 407 patients treated at the Kissy Mental Hospital in Freetown, which found that 79.5% of inpatients and 62.8% of outpatients were diagnosed as psychotic, suggesting that only individuals with severe and disruptive forms of mental disorders seek treatment. Anxiety disorders, which together with depressive disorders are the most commonly observed psychiatric condition, were highly underrepresented in our sample. In the future it would therefore be necessary to design programmes that are able to detect and offer treatment to people with mental disorders that are not accompanied by severe behavioural disturbances, but which nonetheless produce significant distress and functional impairment in the patient.[14]

Our results also highlighted the fact that when patients with severe mental disorders are not offered medication, there is a high risk that they will drop out of psychiatric care. By contrast, when some treatment is provided, help-seeking behaviour is strengthened and this results in a greater demand for services.[5] Consequently, an adequate supply of psychotropic medication at primary healthcare level is an essential first step in the process of decentralisation and the reintegration into society of users with severe mental disorders.[5] To this end, campaigns are required to raise awareness among donor agencies and policy makers in LMICs of the need for a sufficient and constant supply of psychotropic medication. The WHO mhGAP estimated the cost of the basic mental healthcare package for the seven most prevalent neuropsychiatric conditions to be US$3-4 per head of population per year in sub-Saharan Africa.[9] Treatments for common mental disorders are about as cost-effective as antiretroviral treatments for HIV/AIDS, secondary prevention ofhypertension, or glycaemic control for diabetes, before taking into account the other economic benefits of mental healthcare such as reductions in inappropriate use of healthcare, absence from work due to sickness, and premature mortality, which could even outweigh the investment costs.[15] Furthermore, non-economic criteria, such as equitable access to healthcare, human rights protection and poverty reduction might be at least as important within the broader process of setting priorities in mental health.

A substantial number of our patients, especially women, sought help from traditional healers before contacting the mental health programme. Similarly, Gesler and Nahim[13] who found that 35.5% of inpatients and 65.2% of outpatients attending the Kissy Mental Hospital had previously contacted a traditional healer. Given the enormous shortage of skilled mental health human resources in Africa and the great inequities in their distribution, some authors have argued that traditional healers might play a role in the mental healthcare system alongside biomedical providers, although no consensus has been reached on this issue.[16]

Study limitations

First, this is merely a descriptive report of the results of a clinical programme designed to assist people suffering from mental disorders when no psychiatrist is available. It was not designed as a research study or clinical trial, which would have exceeded the methodological limitations of the programme. Although the training course and the direct supervision were specifically tailored and designed for the programme by experienced foreign and local specialists in mental health, it was not until 2010 that standardised and WHO-supported training material could be used to improve the diagnosis and management processes. This may limit the reliability and replicability of our results.

Second, Sierra Leone may not represent other LMICs. Therefore, more locally conducted research is needed to build knowledge about countries that, for example, have not been exposed to armed conflicts but to other poverty-maintaining factors. Patient clinical outcomes were evaluated solely by means of the CGI-I Scale, and no global outcome data were available. In this regard, determining the real efficacy of the programme would require more detailed information about patients' ability to reintegrate within their family, work and social contexts.

Finally, there is a need for objective measures of the quality and quantity of supervision required to enable adequate delivery of mental healthcare by primary care workers. Establishing these measures would require more complex experimental interventions than the present observational design. Nonetheless, this is a key issue that needs to be addressed, not only for determining the validity and true applicability of primary care worker-led mental health programmes, but also for clarifying the role to be played by specialist staff in these programmes.

Conclusion

The ratio of burden to available resources for mental healthcare in LMICs is extremely inequitable, perhaps one of the worst among all major health domains.[3] However, since mental disorders are so inextricably linked to other public health priorities (such as HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health, and diabetes) it is increasingly clear that there can be 'no health without mental health. [4] Effective, locally feasible and affordable treatments for mental disorders do exist in developing countries,[4] but in order to take these further, common mental disorders need to be considered alongside other diseases associated with poverty to attract attention from health policy-makers and donors. However, this is not just an economic question. Government commitment to addressing the need for a mental health policy and legislation, building mental health literacy, and implementing strategies for combating stigma and discrimination for the whole population are also critically important.'51 Given the scarcity of mental health specialists, one option for developing countries might be to decentralise and integrate mental healthcare into routine primary healthcare programmes that are built around collaboration between non-specialist and specialist health workers. However, more data are needed on the benefits, the human resources required, and the costs of such interventions, since current competing priorities and budgetary constraints force resources to be targeted at cost-effective care and prevention strategies for which there is credible evidence of effectiveness.

Acknowledgement. P Alonso received a cooperation grant from Academia de Ciencies Mediques i de la Salut de Catalunya i de Balears.

References

1. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3(11):e442. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442] [ Links ]

2. Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011;378(9802):1592-1603. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60891-X] [ Links ]

3. Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Worldwide use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders: Results from 17 countries in the WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Lancet 2007;370(9590):841-850. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7] [ Links ]

4. Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007;370(9591):991-1005. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9] [ Links ]

5. Petersen I, Ssebunnya J, Bhana A, Baillie K. Lessons from case studies of integrating mental health into primary health care in South Africa and Uganda. Int J Ment Health Syst 2011;5:8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-5-8] [ Links ]

6. United Nations Development Programme. Human development report, 2009. New York: Human Development Report Office, 2009. [ Links ]

7. Donnelly J. How did Sierra Leone provide free health care? Lancet 2011;377(9775):1393-1396. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60559-X] [ Links ]

8. Patel V, Thornicroft G. Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: PLoS Medicine Series. PLoS Med 2009;6(10):e1000160. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000160] [ Links ]

9. World Health Organization. mhGAP Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [ Links ]

10. Dua T, Barbui C, Clark N, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: Summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med 2011;8(11):e1001122. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001122] [ Links ]

11. Guy W (ed). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Heath, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1976. [ Links ]

12. Jenkins R, Kiima D, Njenga F, et al. Integration of mental health into primary care in Kenya. World Psychiatry 2010;9(2):118-120. [ Links ]

13. Gesler WM, Nahim EA. Client characteristics at Kissy Mental Hospital, Freetown, Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med 1984;18(10):819-825. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(84)90149-7] [ Links ]

14. Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T. Common mental disorders and disability across cultures. Results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA 1994;272(22):1741-1748. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03520220035028] [ Links ]

15. Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, et al. Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011;378(9801):1502-1514. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X] [ Links ]

16. Meissner O. The traditional healer as part of the primary healthcare team? S Afr Med J 2004;94(11):901-902. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

P Alonso

mpalonso@bellvitgehospital.cat