Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Psychiatry

versión On-line ISSN 2078-6786

versión impresa ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.20 no.1 Pretoria ene./mar. 2014

ARTICLE

Profile of rape victims referred by the court to the Free State Psychiatric Complex, 2003 - 2009

F J W CalitzI; L de RidderII; N GerickeII; A PretoriusII; J SmitII; G JoubertIII

IBA (Hons), MA (Clin Psych), DPhil. Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

IIMB ChB students, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

IIIBA, MSc. Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The psychological evaluation of rape victims to determine their competency to testify in court and whether they are capable of consenting to sexual intercourse is challenging, especially when the rape victim is mentally retarded.

OBJECTIVE: To describe the profile of mentally retarded rape victims referred to the Free State Psychiatric Complex (FSPC) in Bloemfontein from 2003 to 2009.

METHODS: A descriptive retrospective study was conducted. The study consisted of 137 rape victims referred by the court to the FSPC for psychological evaluation from 2003 to 2009. Patient files were used to obtain information.

RESULTS: The majority of individuals (n=129; 94.2%) in the cohort were female. The mean age of the participants was 19 years (range 3 - 52). The number of victims evaluated increased from four in 2003 to 36 in 2009. Most participants were diagnosed with moderate (67.2%), followed by severe (18.3%) and mild (14.6%) mental retardation. Only two of the victims were able to give legal consent to sexual intercourse. Only one participant was able to testify in a court of law. A noteworthy finding was that in only 25 (18.2%) cases, a clinical psychologist was subpoenaed to testify in court.

CONCLUSION: The vast majority of mentally retarded rape victims in our cohort, regardless of their level of intellectual functioning, were not able to testify in court and were not able to give informed consent to sexual intercourse.

The psychological evaluation of rape victims to determine their competency to testify in court and whether they are capable of consenting to sexual intercourse is challenging, especially when the victim is mentally retarded and the sole witness against the accused. If the mentally retarded rape victim is not competent to testify and insufficient evidence is available, the case will be dismissed and the perpetrator goes free. Failure to prosecute and convict such offenders allows for continued abuse without fear of retribution.[1,2]

Research has found that only 3% of sexual abuse cases against individuals with developmental disabilities are reported in the USA.[3] It has been reported that at least 90% of people with developmental disabilities experience sexual abuse at some point in their lives, and in almost 50% of cases, multiple abusive incidents occur.[4] Sobsey[5] stressed that the likelihood of rape in this group of individuals is staggering, with 15 000 - 19 000 persons with developmental disabilities in the USA being raped each year.[5] An investigation conducted at a Canadian university showed that 20% of cases were reported, and in 99% of cases, the victims were sexually abused by people known to them.[6] Reynolds[7] emphasised that although females (with or without disabilities) represent the largest percentage of all sexually abused individuals, more boys and men with intellectual disabilities are sexually abused than those without disabilities.[7]

In South Africa (SA), the South African Police Service (SAPS) Crime Information Analysis Centre does not provide a separate report of sexual crimes against individuals with mental retardation.[8] According to Pillay and Sargent,[1] this lack of reporting and documentation makes it difficult to estimate the incidence of such crimes in SA, and may perpetuate society's denial of the existence of sexual abuse of individuals with mental retardation. Calitz,[9] however, reported an increase in the referrals of mentally retarded rape survivors to the Free State Psychiatric Complex (FSPC) in Bloemfontein, SA. In 2009, 40 mentally retarded rape victims were referred, and during the first quarter of 2010, 46 new cases were evaluated. By the end of 2010, 90 mentally retarded rape victims were evaluated, thus showing an increase of 125% from 2009.[9]

Mental retardation is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV[10] as 'significantly sub-average general intellectual functioning (having an [intelligence quotient] IQ <70) that is accompanied by significant limitations in adaptive functioning in at least two of the following skills areas: communication, self-care, home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health and safety.' The onset must occur before age 18 years. The DSM-IV also differentiates between four degrees of severity of mental retardation: mild (IQ level 50 - 55 to ~70), moderate (IQ level 35 - 40 to 50 - 55), severe (IQ level 20 - 25 to 35 - 40) and profound (IQ level below 20 - 25) mental retardation. For the purpose of this study, the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV were applied.[10]

The World Health Organization (WHO)'s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)[11] defines mental retardation as 'a condition of arrested or incomplete development of the mind, which is especially characterised by impairment of skills manifested during the developmental period, skills which contribute to the overall level of intelligence, i.e. cognitive, language, motor and social abilities.'[11] The ICD-10 also differentiates between four degrees of severity. The IQ range for mild mental retardation is approximately 50 - 69. As adults, the mental age of these individuals is from 9 years up to, but not including 12 years, and they usually experience some learning difficulties in school. Many adults will be able to work and maintain good social relationships and contribute to society. Individuals with moderate mental retardation have an IQ in the range of 35 - 49. In adults, the mental age of such individuals is from 6 years up to, but not including 9 years, which is likely to result in marked developmental delays in childhood, although most can learn to develop some degree of independence in self-care and acquire adequate communication and academic skills. Adults will need varying degrees of support to live and work in the community. The IQ range for severe mental retardation is approximately 20 to 34. In adults, the mental age is from 3 years up to, but not including 6 years, and they are in continuous need of support. The IQ range for profound mental retardation is <20. As adults, the mental age of such individuals is <3 years, and they present with severe limitations in self-care, continence, communication and mobility.[11] Mental age refers to an age-normed level of performance on an intelligence test. The IQ is an expression of a person's mental age as a percentage of the chronological age. The mental age is usually equal to the chronological age. For instance, an adult who is intellectually disabled, with an IQ of approximately 50 -69, has a mental age of 9 - 12 years. The mental age helps the court to understand on which intellectual level the complainant functions.

In SA, the sexual activity of a mentally disabled person is regulated by the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007,[12] which defines mentally disabled as: 'a person affected by any mental disability, including any disorder or disability of the mind, to the extent that he or she, at the time of the alleged commission of the offence in question, was: (a) unable to appreciate the nature and reasonably foreseeable consequences of a sexual act; (b) able to appreciate the nature and reasonably foreseeable consequences of such an act, but unable to act in accordance with that appreciation; (c) unable to resist the commission of any such act; or (d) unable to communicate his or her unwillingness to participate in any such act.'[12]

During the psychological evaluation of a rape survivor, the court requires the following questions to be answered: (i) is the rape survivor mentally retarded?; (ii) is the rape survivor able to provide testimony in court?; and (iii) is the complainant capable of consenting to sexual intercourse? A further question that sometimes arises (mainly from the defence), is whether the complainant's mental deficiency would be discernible to the average person.[13]

Advocate Elsabé Kraft, head of Sexual Offences at the Bloemfontein Regional Court, described the legal process in an interview with the authors, as follows (personal communication): 'If the case is eventually reported, the court will immediately send the rape victim for a medical examination in search of traces of DNA or any clue to help with the case. The mentally retarded rape victim will be referred by the court for a psychiatric evaluation to determine the mental age and severity of mental retardation. The rape victim will be treated during their trial according to their age equivalent determined by the test. The justice system protects the persons who are particularly vulnerable because of mental impairment by not allowing them to testify in the courtroom itself. They rather make use of the camera system, where the victim is interviewed in an environment that is free of stress and intimidation. These cases are challenging because of the above mentioned elements.'

Inspector Arlene Snyman of the SAPS, Park Road Family Violence, Children Protection and Sexual Offences Unit in Bloemfontein, is of the opinion that some mentally retarded rape victims are able to testify (personal communication). She referred to a 21-year-old mentally retarded woman who was raped by a first-time offender and who was able to testify in court with the support of her sister. The case started in 2005 and closed in 2008. The abuser was given an 18-year sentence. Inspector Snyman also stated that a sentence for raping a mentally retarded person is more severe than that of raping a normal individual. She mentioned that, in contrast to the past, life sentences can now also be handed down in a Regional Court as well as in the High Court.

Pillay and Sargent,[1] who evaluated ten rape victims with possible mental retardation, found that six of the eight survivors with mental retardation were able to provide a clear account of the alleged rape and were therefore considered able to give evidence in court with some support. Two of the rape survivors did not show mental retardation. One of the remaining survivors was able to relay some details of her ordeal, but required more extensive support and sensitive questioning in order to cope with court proceedings. The other survivor with mental retardation was mute, and had not acquired any sign-language skills. She was unable to provide details of the rape.[1]

In another study by Pillay,[14] 106 rape survivors were evaluated for possible mental retardation. Most (91.5%) were female, 21.7% were aged <16 years, and over two-thirds were from rural communities. In 77.4%, the alleged perpetrators were people they had previously seen in the community but had not befriended. Almost 96% were diagnosed with mild (n=16; 15.2%), moderate (n=43; 40.6%), severe (n=41; 38.7%) and profound (n=2; 1.9%) mental retardation, while >90% were able to testify. However, approximately two-thirds (65.1%) were not able to make an informed decision to consent to sexual intercourse.[14]

In a similar study, Todd[15] assessed 143 complainants during a one-year period in the Sexual Abuse Victim Empowerment Programme of the Western Cape Province. The study included 134 females and 9 males (age range 8 - 60 years). The age group at greatest risk for sexual abuse was age 12 - 22 years. Many (39.4%) of the sexual crimes occurred outside the victim's neighbourhood, and included day-care facilities, institutions and transport systems. Of the remaining cases, 31.3% occurred in the complainant's neighbourhood and 28.5% took place inside their homes. Most complainants were moderately mentally retarded (IQ 35 - 40 or 50 - 55) with an average age-equivalent of 6 years. Todd[15] also found significant differences in the sexual knowledge of people in the various levels of cognitive deficit in the research group. Regardless of their level of cognitive deficit, they could not give consent to sexual intercourse, since the level of their intellectual and adaptive functioning was such that they had the mental age equivalent of minors.[15]

Sobsey and Doe[16] analysed 162 reports on the profiles of persons who had sexually abused individuals with disabilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the offenders were service providers, and 19% were biological or step-family members. Other findings showed that 15.2% were acquaintances, 9.8% were informal paid service providers (e.g. babysitters) and 3.8% were dates.[16] In a similar study, Meel[17] found that in 90.6% of cases, a close relative was implicated in the rape.

Only a few recent studies[1,14,15,17] conducted on mentally retarded rape victims in SA could be located in the literature.

Objective

The aim of this study was to describe the profile of mentally retarded rape victims referred to the FSPC in Bloemfontein in the period 2003 - 2009.

Methods

A descriptive, retrospective study was conducted. One hundred and thirty-seven rape victims referred by the court for psychological evaluation to the FSPC from 2003 to 2009 were included in the study. The reason for the evaluation was for intellectual assessment with a view to determine their ability to testify in court and their ability to give consent to sexual intercourse. Information was obtained with regard to these individuals' sociodemographic background, degree of mental retardation, ability to consent to sexual intercourse, ability to testify appropriately in court, and any expert witnesses subpoenaed to testify in court. The assessment of each individual included: (i) an interview with the victim; (ii) interviews with family members; (iii) information from the police docket; (iv) psychometric testing, where possible; and (v) the use of interpreters, where required.

A data-capture sheet was compiled to record the relevant information from the rape victims' clinical files. A pilot study on ten files of victims preceded the main study. A primary reason for the pilot study was to ensure the utility of the data and data sheet. Some minor changes had been made to the data sheet; therefore, the results of the pilot study were not included here.

Data analysis was performed by the Department of Biostatistics, University of the Free State (UFS). Results were summarised as frequencies and percentages in the case of categorical variables, and means or percentiles for numerical variables.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, UFS. Permission to access the patient files was obtained from the Chief Executive Officer of the FSPC.

Results and discussion

Sociodemographics

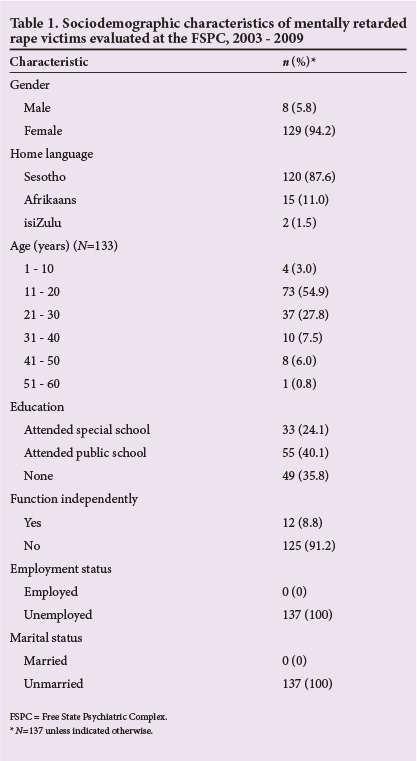

Table 1 summarises participants' sociodemographic information. Of the 137 rape victims included, 129 (94.2%) were female. Most of the victims' home language was Sesotho («=120; 87.6%), reflecting the demographic composition of the population of the Free State Province. The mean age was 19 years (range 3 - 52). Most participants (54.9%) were within the 11 - 20-year age group, followed by 21 - 30 (27.8%) and 31 - 40 (7.5%) years. Results from a similar investigation in the Western Cape Province[15] support this finding, with the majority of victims aged 12 - 22 years.

None of the participants in our study were married and all were unemployed. One hundred and twenty-four (90.5%) were not able to function independently and needed constant supervision. The remaining participants could only socialise minimally with peers and family. Regarding scholastic training, 49 (35.8%) never attended school, 55 (40.1%) attended public schools and 33 (16.8%) went to special schools.

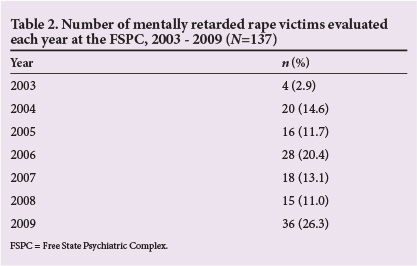

Number of participants evaluated, 2003 - 2009

Table 2 denotes the number of participants evaluated per annum from 2003 to 2009. Approximately one-quarter (n=36; 26.3%) of the participants were evaluated in 2009, followed by 26 (20.4%) in 2006. The number evaluated increased from four in 2003 to 36 in 2009. The main reason for this could be an increased awareness of the rights of the mentally retarded person, resulting in incidents being reported more readily by caregivers and family members in recent years. Another explanation could be that the service at the FSPC became known to the public and prosecutors might also have made use of the service more often.

Relationship between the victim and offender

Data on the relationship between the victim and the accused were available for only 53 (38.7%) of the referred victims. Of the 53 offenders accused in these cases, 32 (60.4%) were acquaintances from the community and were known to the victim, while 15 (28.3%) were people who lived in the same house as the victims, either as family, a stepfather or a boyfriend of the mother. One of the offenders worked at the school the victim attended. Another six accused were close friends or boyfriends of the victim. From these results, it is clear that the majority of offenders were people known to the victim. These findings are supported by similar studies conducted elsewhere.[1,13-16]

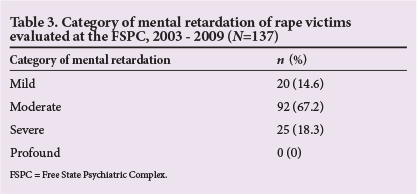

Diagnoses

The psychiatric diagnoses of the participants are presented in Table 3. Most were diagnosed with moderate (67.2%), followed by severe (18.3%) mental retardation. In a similar study by Pillay,[14] 15.2% of the study population were diagnosed with mild, 40.6% with moderate, 38.7% with severe and 1.9% with profound mental retardation.

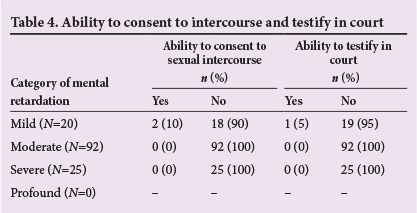

Ability to consent to intercourse and testify in court

Data on ability to consent to intercourse are presented in Table 4. Most (n=135; 98.5%) participants were not able to give consent to intercourse, with only two (1.5%) found to be able to do so. Todd[15] found significant differences in the sexual knowledge of people in the various levels of cognitive deficit in her research group. Furthermore, the vast majority (n=136; 99.3%) of participants in our study lacked the ability to testify in court (Table 4).

Expert witness subpoenaed to testify in court

An inexplicable finding was that in only 25 (18.2%) of the 137 cases, the clinical psychologist involved in the case was subpoenaed to testify in court. This finding appears to indicate that both the court and the defence accepted the report of the clinical psychologist in the remainder of the cases, or alternatively, those cases have not been heard yet or were withdrawn.

Conclusion

From our results, it was clear that most of the rape victims were mentally retarded, and regardless of their level of intellectual functioning, were not able to testify in court and not able to give informed consent to sexual intercourse.

This finding has serious consequences for mentally retarded rape victims in the Free State Province. If a rape victim with mental retardation was considered incompetent and denied the right to testify in court, the court would have to rely on sufficient evidence obtained by the police investigation and other forms of evidence, such as DNA tests. Without such evidence, the perpetrator would walk free. It is therefore important that the use of a mediator is promoted for mentally retarded rape victims in court, and that members of the SAPS receive training in the proper handling of these cases. Another important factor reflected by the findings of the study is the role of the home language of the rape victim in the assessment. It is recommended that institutions who evaluate rape victims appoint or train interpreters to support the evaluators in their assessment. Findings from this and other relevant studies should be provided to the National Government and the Provincial Government of the Free State in order to raise awareness of the magnitude of the problem.

The single-most pertinent issue raised by this study concerns the final outcome of each of the 137 cases. What was the fate of the victims? What befell the perpetrators? Although the principal researcher was called upon to testify in 25 cases (18.2%), neither the outcome of those cases nor the process followed in the remaining 112 (81.8%) cases is currently known. Future research should follow up on all cases to determine the outcomes. Those results should then inform clinical practice and recommendations to the authorities and the Department of Justice.

Although the present study provided noteworthy findings, the results should be interpreted with care, especially with regard to generalisation. Only rape victims from the Free State Province were referred to the FSPC and were included in the study. A study limitation was that some files were incomplete or not completed correctly. Nevertheless, the study contributes substantially to important data regarding the demographics, degree of mental retardation, ability to testify appropriately in court and ability to give consent to intercourse in mentally retarded rape victims in a field that has been largely neglected in SA.

Acknowledgement. We thank Dr L M van der Merwe for proofreading the protocol. Dr Daleen Struwig, medical writer, Faculty of Health Sciences, UFS, is acknowledged for technical and editorial preparation of the manuscript for publication.

References

1. Pillay AL, Sargent C. Psycho-legal issues affecting rape survivors with mental retardation. S Afr J Psychol 2000;30(3):9-13. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124630003000302] [ Links ]

2. Pillay AL, Kritzinger AM. Psycho-legal issues surrounding the rape of children and adolescents with mental retardation. J Child Adolesc Mental Health 2008;20(2):123-131. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2989/JCAMH.2008.20.2.8.691] [ Links ]

3. Tharinger D, Horton CB, Millea S. Sexual abuse and exploitation of children and adults with mental retardation and other handicaps. Child Abuse Negl 1990;14(3):301-312. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(90)90002-B] [ Links ]

4. Valenti-Hein D, Schwartz L. The Sexual Abuse Interview for Those With Developmental Disabilities. Santa Barbara: James Stanfield Company, 1995. [ Links ]

5. Sobsey D. Violence and Abuse in the Lives of People With Disabilities: The End of Silent Acceptance? Baltimore: Paul H Brookes Publishing Company, 1994. [ Links ]

6. Senn CY. Vulnerable: Sexual Abuse and People With an Intellectual Handicap. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/ 0000019b/80/1e/53/90.pdf(accessed 22 October 2009). [ Links ]

7. Reynolds LA. People With Mental Retardation & Sexual Abuse. http://www.er.rs/forum/index.php?topic=974.0;wap2 (accessed 3 May 2013). [ Links ]

8. South African Police Service. Crime in the RSA - April to March 2008/2009. http://www.saps.gov.za/statistics/reports/crimestats/2009/pdf/rsa_total.pdf (accessed 3 May 2013). [ Links ]

9. Calitz FJW. Psycho-legal challenges facing the mentally retarted rape victim. South African Journal of Psychiatry 2011;17(3):2-6. [ Links ]

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision (DSM-IV TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2004 [ Links ]

11. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th ed. Geneva: WHO, 2007. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online2007/ (accessed 20 January 2010). [ Links ]

12. Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Republic of South Africa. Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act No. 32 of 2007. Cape Town: Juta & Co., 2007. [ Links ]

13. Artz L, Roehrs S. Criminal Law (Sexual and Related Matters) Amendment Act (No. 32 of 2007): Emerging issues for the health sector. Continuing Medical Education 2009;27(10):464-465. [ Links ]

14. Pillay AL. An audit of competency assessments on court-referred rape survivors in South Africa. Psychol Rep 2008;103(3):764-770. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/PR0.103.7.764-770] [ Links ]

15. Todd RMJ. Sexual abuse victim empowerment programme: An archival study assessing the relationship between demographics and level of intellectual functioning. Unpublished Master's Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2005. [ Links ]

16. Sobsey D, Doe T. Patterns of sexual abuse and assault. Sexuality and Disability 1991;9(3):243-259. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01102395] [ Links ]

17. Meel B. Prevalence of HIV among victims of sexual assault who were mentally impaired children (5 to 18 years) in the Mthata area of South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2009;1(1):1-3. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v1i1.5] [ Links ]

Corresponding author: F J W Calitz (calitzfjw@fshealth.gov.za)