Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Journal of Radiology

versão On-line ISSN 2078-6778

versão impressa ISSN 1027-202X

S. Afr. J. radiol. (Online) vol.27 no.1 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajr.v27i1.2684

PICTORIAL REVIEW

Pictorial review of the post-operative cranium

Varsha Rangankar; Anmol Singh; Sanjay Khaladkar

Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pune, India

ABSTRACT

Imaging evaluation of the brain and cranium after cranial surgery is a routine and significant part of the workflow of a radiology department. Various normal expected findings and early and late complications are associated with the post-operative cranium. In this pictorial review, the authors describe the typical imaging features of the spectrum of various conditions associated with cranial surgery with illustrative cases.

CONTRIBUTION: A good knowledge and understanding of the spectrum of imaging appearances in the post-operative cranium is vital for the radiologist to accurately diagnose potential complications and distinguish them from normal post-operative findings, improving patient outcomes and guiding further treatment

Keywords: cranium; craniotomy; craniectomy; complications; post-operative; Trephine syndrome; tension pneumocephalus; paradoxical herniation.

Introduction

Surgical procedures like burr holes, craniotomy and cranioplasty are commonly performed for various neurosurgical indications such as intra-axial and extra-axial haemorrhages and collections, tumours, and infections.1 Imaging, especially CT, is often performed in the post-operative follow-up of these patients. When interpreting these scans, it is imperative to be aware of the operative procedure performed and the expected post-operative findings, such as pneumocephalus, routine post-operative inflammatory changes and haemorrhages. At the same time, radiologists need to be vigilant of the abnormal imaging findings and be able to identify the various associated post-operative complications such as infections, tension pneumocephalus, sinking flap and herniation.

CT is the first-line modality for these cases, because of short scan times and accessibility, and is routinely used for post-surgical follow-up. While MRI is better than CT for certain conditions such as infection, intracranial collections and ischemia, it is often limited by incompatibility or artifact related to surgical material and implants. This article discusses the surgical techniques with expected imaging findings and describes the important post-operative complications.

Neurosurgical techniques and imaging appearances

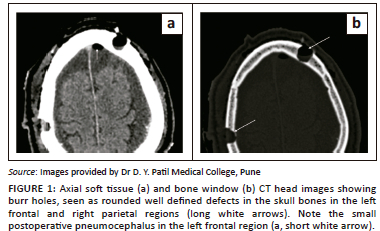

Burr holes

Burr holes are small holes that are made in the skull bones using a surgical drill. The usual indications include insertion of a device such as a ventricular drain, endoscope or a deep brain stimulator electrode, drainage of a subdural haematoma and provision of access for stereotactic brain biopsy.1 On CT, a burr hole appears as a focal well-defined defect in the calvarium (Figure 1). In the acute setting, associated subgaleal or extradural fluid collections and tiny air foci may be seen.2

Craniotomy

Craniotomy is the surgical removal of a segment of the calvarium to achieve neurosurgical exposure (Figure 2a). The calvarial segment is replaced at the end of the procedure. The various types of craniotomies include fronto-spheno-temporal, sub-temporal, anterior or posterior parasagittal, median suboccipital and lateral suboccipital.3 The margins of the bone flap are sharp and well defined, with a tram track appearance on CT images in the early post-operative period. Later on, the edges become smooth and rounded as the flap undergoes resorption and remodelling.4

Craniectomy

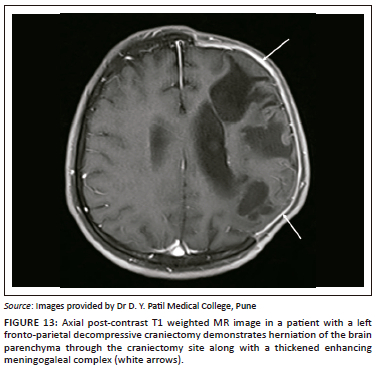

In contrast with craniotomy, the surgically removed segment of skull bone is not replaced at the end of the procedure in craniectomy (Figure 2). Usual indications are decompression of intracranial contents and removal of an infected bone flap.5 The bone flap is usually stored in an abdominal subcutaneous pocket for subsequent cranioplasty. Post-craniectomy, the subgaleal space is usually obliterated, with formation of a meningogaleal complex, which consists of the galea aponeurotica, connective and fibrous tissue, and the duramater (Figure 2b). On CT, this meningogaleal complex manifests as a thin, smooth, slightly hyperattenuating layer that enhances mildly on post-contrast images.6 In the chronic phase, calcifications of the meningogaleal complex are commonly seen (Figure 2c).

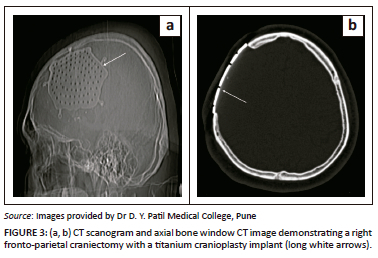

Cranioplasty

Cranioplasty is a surgical procedure performed to reconstruct a patient's skull, usually following a previous surgical intervention; or less commonly, in the setting of a congenital defect or after trauma.7 The goal of the procedure is to protect the brain from mechanical damage and improve cosmesis. Ideally, the cranioplasty implant should be biocompatible, strong and durable to resist deformation, radiolucent to allow clean visualisation of the underlying brain tissue on CT and also MRI compatible.7 Commonly used materials for cranioplasty include autologous bone grafts and synthetic materials such as polymethyl methacrylate, titanium (Figure 3), or ceramics.

Post-operative findings and complications

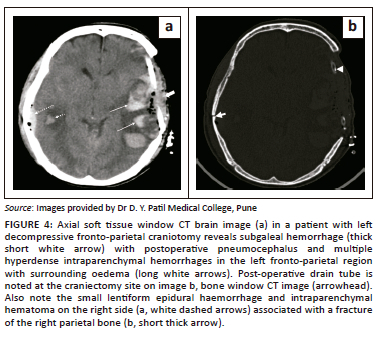

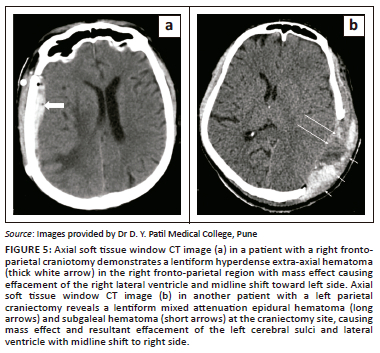

Post-operative haemorrhages

Small scalp and extradural haemorrhages are relatively common and benign findings in the post-operative period. Only about 1% of post-craniotomy intracranial haemorrhages require surgical intervention.8 The most common post-operative haematomas are intraparenchymal (43%) (Figure 4), extradural haematoma (33%), subdural haematoma (5%) and mixed (8%) (Figure 5).8

Extradural haematomas are situated between the dura and the inner table of the skull. The majority of the post-operative extradural hematomas are regional, in the location related to the surgical site.9 Further subtypes are adjacent haematomas that occur at the margins of the craniotomy site and remote extradural haematomas, located distant from the craniotomy site.10 The majority of intraparenchymal haemorrhages are small (less than 3 cm in size) and do not cause much neurological compromise. Large haematomas are associated with poorer outcomes.1 Causes of large intraparenchymal haemorrhages include poor haemostasis, excessive brain retraction, hypertension in the post-operative period and bleeding disorders.

Infections

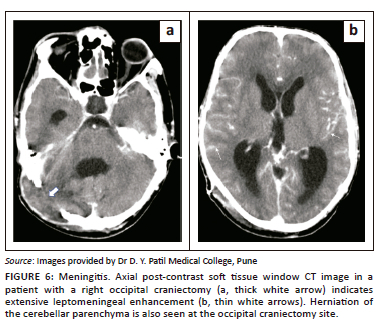

Post-craniotomy infections are a relatively uncommon complication, with an incidence of less than 1% described in the literature, and usually present as extradural abscesses, meningitis (Figure 6), subdural empyema and parenchymal abscesses.11,12 The infection usually begins in the subcutaneous plane at the surgical site and extends to the deeper tissues. Contrast imaging plays an important role in diagnosing involvement of the bone flap, extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces, meninges and brain parenchyma.

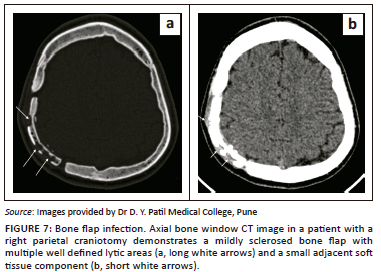

Bone flap infections account for nearly half of all post-craniotomy infections12 and usually present 1-2 weeks after surgery. Risk factors include intra-operative breach of the paranasal sinuses, presence of an active infective focus during the surgery, surgery performed for traumatic injuries, longer surgical duration, re-operation, immunodeficient status and post-procedure CSF leakage.13 Detached bone flaps are also more likely to get infected as they lack a vascular supply.

On CT, the bone flap may show an irregular outline with multiple lytic areas or sclerosis of the bone flap (Figure 7). Presence of superficial skin thickening, fat stranding and subgaleal and extradural fluid collections in the presence of bony changes increases the specificity for the diagnosis (Figure 8). On MRI, the marrow of the involved bone appears hypointense on T1 weighted images and hyperintense on T2 weighted images, with diffusion restriction.

Extradural abscesses present as biconvex fluid collections, usually adjacent to the craniotomy site, with thickened enhancing dura on contrast enhanced images (Figure 8 and Figure 9).14 Subdural empyemas present as extra-axial crescentic fluid collections along the cerebral convexity.14

Large subdural empyemas may be associated with subfalcine herniation, significant effacement of the ventricles and sulci and cerebral oedema. These collections are hypointense on T1 weighted images, hyperintense on T2 weighted images and mildly hyperintense to CSF on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. They may show diffusion restriction and peripheral rim enhancement (Figures 10a-f). Rarely, the collection can extend into the brain parenchyma and intraparenchymal abscesses can rupture into the ventricle leading to ventriculitis (Figures 10g and h).15

Extracranial herniation

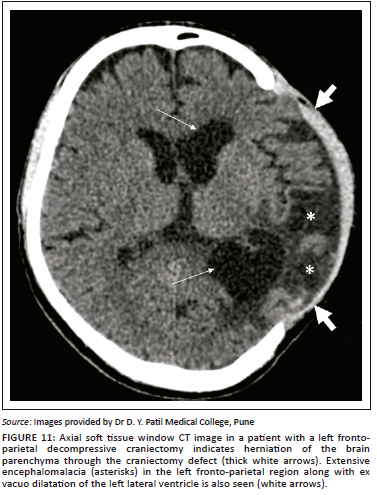

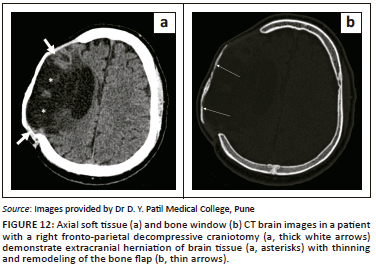

In cases of raised intracranial pressure from any aetiology, such as cerebral oedema or haemorrhage; the oedematous brain parenchyma herniates via the craniectomy defect (Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13). This leads to compression and contusions in the parenchyma at the bony margins of the craniectomy and compression of the superficial cortical veins leading to infarction.16

Tension pneumocephalus

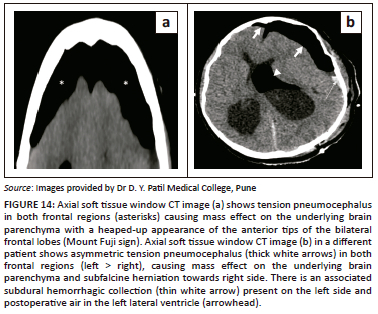

Unlike post-operative pneumocephalus, which is an expected finding in the post-operative cranium, tension pneumocephalus is a rare and life-threatening entity. There is build up subdural air that causes compression of the brain parenchyma (Figure 14). It most commonly results from a ball-valve mechanism that causes entry of air into the subdural space.17

The diagnosis of tension pneumocephalus is made on CT in the presence of subdural air with the 'peaking' sign and the 'Mount Fuji' sign (Figure 14a). 'Peaking' sign refers to mass effect on the frontal lobes because of the presence of subdural air and the 'Mount Fuji' sign refers to separation of the frontal lobes from the falx.18

Subdural and subgaleal hygromas

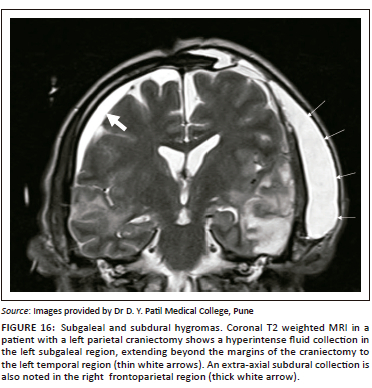

Subdural and subgaleal hygromas are early complications that usually occur as a result of altered CSF circulation dynamics in the post-operative period leading to CSF accumulation in the subdural or the subgaleal region, most commonly on the side of the surgery.16 Rarely, however, they can also be seen on the opposite side or in the interhemispheric region.19 The fluid collections accumulate in the first few days following the surgery and resolve spontaneously over weeks or months. They follow CSF attenuation and signal intensity on CT (Figure 15) and MRI (Figure 16) images, respectively and generally do not cause any significant neurological compromise.

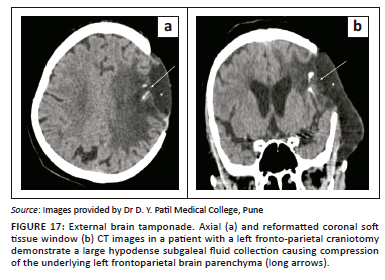

External brain tamponade

External brain tamponade is a rare, life-threatening condition. It is characterised by excessive subgaleal fluid accumulation that exerts pressure on the underlying brain parenchyma. Clinically, the patient presents with neurological deterioration and a tense craniectomy flap. Imaging shows a subgaleal fluid collection producing mass effect on the brain (Figure 17). Midline shift and sub-falcine herniation may be seen in severe cases. Drainage of the subgaleal fluid usually leads to neurological improvement.20

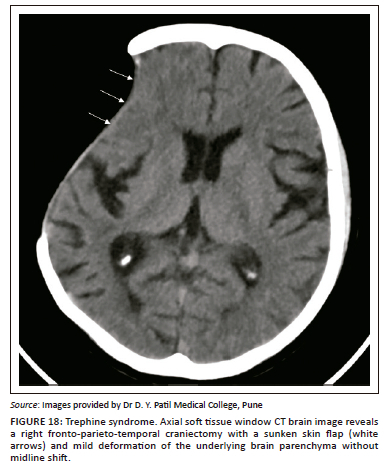

Sinking skin flap syndrome

Sinking skin flap syndrome, or Trephine syndrome, is an intermediate to late post-operative complication in patients who undergo craniectomy. There is a sunken appearance of the skin flap and concave appearance of the underlying parenchyma due to chronic exposure of the brain to atmospheric pressure causing deformity of the underlying parenchyma (Figure 18).21 Unlike paradoxical herniation, there is no midline shift, subfalcine or uncal herniation. The patients usually present with vague complaints such as headache, dizziness, mood changes and fatiguability.21

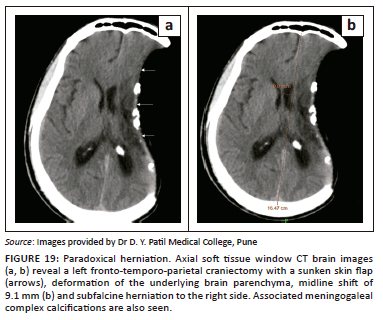

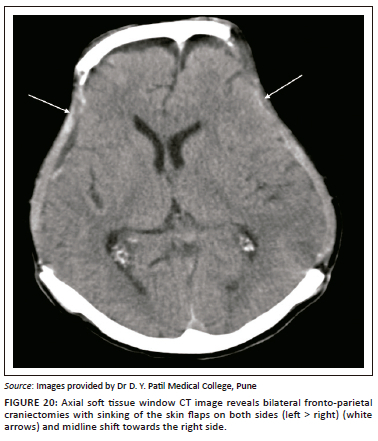

Paradoxical herniation

Paradoxical herniation is a rare, late complication in the post-craniectomy patient. It is characterised by a sunken skin flap and contralateral displacement and herniation of brain, with resultant mass effect, midline shift and effacement of CSF spaces (Figure 19 and Figure 20).20 The mechanism is usually a decrease in intracranial pressure because of lumbar puncture, ventricular drainage or ventriculoperitoneal shunting, which leads to an imbalance in the intracranial pressure and the atmospheric pressure. It is a potentially life-threatening condition, usually treated by clamping any shunts or drains, putting the patient in the Trendelenberg position, administering fluids and performing an early cranioplasty.22

Conclusion

Imaging plays a crucial role in the assessment of the post-operative cranium, providing valuable information about potential complications and helps in optimising treatment. Radiologists should be familiar with the different early and late complications to provide accurate and timely diagnoses. With proper imaging interpretation, clinicians can make informed decisions regarding patient management, ultimately leading to better post-surgical outcomes and improved patient care.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

V.R. conceptualised this article. A.S. collected the relevant data and references and prepared the primary article draft. V.R. and S.K. reviewed and edited the final draft of the manuscript and selected the images.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research. Written consent was obtained from the patients for publication of the radiological images. All the images were anonymised to protect the identity of the patients.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Original images and any required information are available on request from the corresponding author, A.S.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official position of the institution.

References

1. Sinclair AG, Scoffings DJ. Imaging of the post-operative cranium. RadioGraphics. 2010;30(2):461-482. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.302095115 [ Links ]

2. Lanzieri CF, Larkins M, Mancall A, et al. Cranial postoperative site: MR imaging appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1988;9(1):27-34. [ Links ]

3. Clatterbuck RE, Tamargo RJ. Surgical positioning and exposures for cranial procedures. In: Winn RD, editor. Youmans neurological surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2003; p. 623-631. [ Links ]

4. Carrau RL, Weissman JL, Janecka IP, et al. Computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging following cranial base surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(9):951-959. https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199109000-00005 [ Links ]

5. Hutchinson P, Timofeev I, Kirkpatrick P. Surgery for brain edema. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(5):E14. https://doi.org/10.3171/foc.2007.22.5.15 [ Links ]

6. Lanzieri CF, Som PM, Sacher M, Solodnik P, Moore F. The postcraniectomy site: CT appearance. Radiology. 1986;159(1):165-170. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.159.1.3952302 [ Links ]

7. Laidlaw J. Cranioplasty. In: Kaye AH, Black PM, editors. Operative neurosurgery. Volume 1. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, 2000; p. 303-314. [ Links ]

8. Palmer JD, Sparrow OC, Iannotti F. Postoperative hematoma: A 5-year survey and identification of avoidable risk factors. Neurosurgery. 1994;35(6):1061-1064; discussion 1064-1065. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-199412000-00007 [ Links ]

9. Fukamachi A, Koizumi H, Nagaseki Y, Nukui H. Postoperative extradural hematomas: Computed tomographic survey of 1105 intracranial operations. Neurosurgery. 1986;19(4):589-593. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-198610000-00013 [ Links ]

10. Wolfsberger S, Gruber A, Czech T. Multiple supratentorial epidural haematomas after posterior fossa surgery. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27(2):128-132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-003-0315-4 [ Links ]

11. McClelland S, 3rd, Hall WA. Postoperative central nervous system infection: Incidence and associated factors in 2111 neurosurgical procedures. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(1):55-59. https://doi.org/10.1086/518580 [ Links ]

12. Dashti SR, Baharvahdat H, Spetzler RF, et al. Operative intracranial infection following craniotomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24(6):E10. https://doi.org/10.3171/FOC/2008/24/6/E10 [ Links ]

13. Mollman HD, Haines SJ. Risk factors for postoperative neurosurgical wound infection. A case-control study. J Neurosurg. 1986;64(6):902-906. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1986.64.6.0902 [ Links ]

14. Ackerman LL, Traynelis VC. Dural space infections: Cranial subdural empyema and cranial epidural abscess. In: Osenbach RK, Zeidman SM, editors. Infections in neurological surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1999; p. 85-99. [ Links ]

15. Harris L, Munakomi S. Ventriculitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [Updated 2023 Feb 12; cited 2023 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544332/ [ Links ]

16. Yang XF, Wen L, Shen F, et al. Surgical complications secondary to decompressive craniectomy in patients with a head injury: A series of 108 consecutive cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(12):1241-1247; discussion 1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-008-0145-9 [ Links ]

17. Reasoner DK, Todd MM, Scamman FL, Warner DS. The incidence of pneumocephalus after supratentorial craniotomy. Observations on the disappearance of intracranial air. Anesthesiology. 1994;80(5):1008-1012. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199405000-00009 [ Links ]

18. Michel SJ. The Mount Fuji sign. Radiology. 2004;232(2):449-450. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2322021556 [ Links ]

19. Yang XF, Wen L, Li G, Zhan RY, Ma L, Liu WG. Contralateral subdural effusion secondary to decompressive craniectomy performed in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: Incidence, clinical presentations, treatment and outcome. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18(1):16-20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000163040 [ Links ]

20. Akins PT, Guppy KH. Sinking skin flaps, paradoxical herniation, and external brain tamponade: A review of decompressive craniectomy management. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9(2):269-276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-007-9033-z [ Links ]

21. Dujovny M, Agner C, Aviles A. Syndrome of the trephined: Theory and facts. Crit Rev Neurosurg. 1999;9(5):271-278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003290050143 [ Links ]

22. Seinfeld J, Sawyer M, Rabb CH. Successful treatment of paradoxical cerebral herniation by lumbar epidural blood patch placement: Technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(3):Suppl:e175; discussion e175. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000289731.27706.af [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Anmol Singh

asmzndpu2018@gmail.com

Received: 29 Mar. 2023

Accepted: 06 June 2023

Published: 21 July 2023