Servicios Personalizados

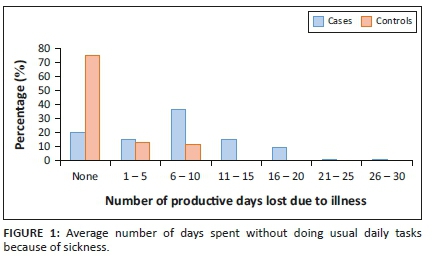

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine

versión On-line ISSN 2078-6751

versión impresa ISSN 1608-9693

South. Afr. j. HIV med. (Online) vol.21 no.1 Johannesburg 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v21i1.1105

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Patient acceptance of HIV testing services in rural emergency departments in South Africa

Aditi RaoI; Caitlin KennedyI; Pamela MdaII; Thomas C. QuinnIII, IV; David SteadV, VI; Bhakti HansotiI, III

IDepartment of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, United States of America

IINelson Mandela Academic Clinical Research Unit, Mthatha, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, United States of America

IVDivision of Intramural Research, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, United States of America

VDepartment of Medicine, Frere and Cecilia Makiwane Hospitals, East London, South Africa

VIDepartment of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University, East London, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: South Africa faces the highest burden of HIV infection globally. The National Strategic Plan on HIV recommends provider-initiated HIV counselling and testing (HCT) in all healthcare facilities. However, HIV continues to overwhelm the healthcare system. Emergency department (ED)-based HCT could address unmet testing needs.

OBJECTIVES: This study examines the reasons for accepting or declining HCT in South African EDs to inform the development of HCT implementation strategies.

METHOD: We conducted a prospective observational study in two rural EDs, from June to September 2017. Patients presenting to the ED were systematically approached and offered a point-of-care test in accordance with national guidelines. Patients demographics, presenting compaint, medical history and reasons for accepting/declining testing, were recorded. A pooled analysis is presented.

RESULTS: Across sites, 2074 adult, non-critical patients in the ED were approached; 1880 were enrolled in the study. Of those enrolled, 19.7% had a previously known positive diagnosis, and 80.3% were unaware of their HIV status. Of those unaware, 90% patients accepted and 10% declined testing. The primary reasons for declining testing were 'does not want to know status' (37.6%), 'in too much pain' (34%) and 'does not believe they are at risk' (19.9%).

CONCLUSIONS: Despite national guidelines, a high proportion of individuals remain undiagnosed, of which a majority are young men. Our study demonstrated high patient acceptance of ED-based HCT. There is a need for investment and innovation regarding effective pain management and confidential service delivery to address patient barriers. Findings support a routine, non-targeted HCT strategy in EDs.

Keywords: HIV counselling and testing; South Africa; emergency department; patient acceptance; implementation research; linkage to care.

Introduction

South Africa (SA) faces the highest burden of HIV infection globally, with 7.7 million people living with HIV (PLWH) and prevalence ranging from 12.6% to 27% across the country.1,2 In 2018, SA had 240 000 new HIV infections and 71 000 AIDS-related deaths.1 The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) adopted the ambitious treatment target of 90-90-90, wherein by 2020 90% of all PLWH would know their status, 90% of whom would be receiving sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART), of whom 90% would have achieved viral suppression.3 Currently, in SA, an estimated 90% of PLWH know their status, of whom 68% are accessing ART, and 87% of these have achieved viral suppression.1 Over the past two decades, numerous steps have been taken by the government to deliver evidence-based interventions focusing on HIV prevention, treatment, and retention. These efforts include the expansion of condom distribution, a national voluntary medical male circumcision program, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, as well as initiatives to increase knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS in communities utilising healthcare, in educational infrastructures and social media.2,4 However, despite sustained efforts and innovative measures, critical coverage gaps remain, with an estimated 10% of HIV-positive South Africans unaware of their status5 and with 15% of new global infections occurring in the country.2

The first critical step to meeting the 90-90-90 target is HIV testing. Early detection of undiagnosed HIV infection followed by effective linkage to care and treatment extends life expectancy, improves the quality of life, and reduces HIV transmission.6 Since 2015, the South African National Strategic Plan on HIV, sexually transmitted infections and tuberculosis has recommended provider-initiated HIV counselling and testing (HCT) to all persons attending healthcare facilities as a standard component of medical care, including trauma, casualty, and specialty clinics.6,7 Nonetheless, the provision of HCT in healthcare facilities is often hindered by the lack of standardised training and by competing clinical care priorities that prohibit effective service delivery.5,7 In addition, resources for HCT have largely been directed to primary healthcare centres and antenatal clinics or are focused on high-risk populations such as sex workers, men who have sex with men, injection drug users, and prisoners.8,9 As a result, individuals who do not interact with the healthcare system through these channels, such as young men, often miss being tested.

In SA, 90% of the population accesses healthcare through the public sector. For 28%, the emergency department (ED), a setting that provides high-volume care, is their only point of contact.10 In the United States of America, the ED is recognised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to be a crucial venue in implementing the national HIV testing strategy.11 Seminal studies have not only quantified the burden of HIV infection in EDs but also have been critical to shaping the US national strategy for HIV; they could similarly address unmet testing needs in SA.11,12,13,14 In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), HIV prevalence in EDs may be high, for example, 19% in Papua New Guinea and 50% in Uganda.15,16 Provision of HIV testing in the ED could thus be a critical intervention in curbing the epidemic. Its acceptance in acute care settings, however, has not been widely evaluated in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies have primarily focused on rates of acceptance, without exploring the reasons behind patients' decisions. Ascertaining the perspectives of patients, especially of those who decline testing, enables the identification of barriers to service delivery and the development of effective strategies to increase HIV diagnosis and linkage to care.

In this exploratory observational study, to determine the feasibility of expanding an ED-based HIV testing strategy in SA, we investigated patient perspectives on accepting or declining HCT and quantified the burden of HIV infection in the ED while implementing the nationally recommended HCT programme. This study will assist policymakers and healthcare providers to inform the integration of HCT in the clinical care pathway and optimise HCT service delivery in this venue, resulting in early engagement in care and treatment initiation, ultimately reducing HIV-associated morbidity and mortality.

Methods

The Walter Sisulu Infectious Diseases Screening in Emergency Departments (WISE) Study was a prospective observational study. HIV counselling and testing was implemented in the EDs of the Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital (NMAH) and the Mthatha Regional Hospital (MRH) in the Eastern Cape Province, from 27 June to 03 September 2017.

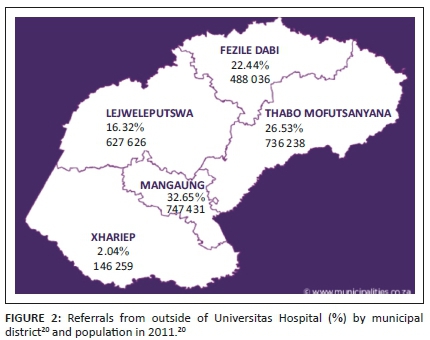

Study site

The study was conducted in Mthatha, a rural town in the South African province of the Eastern Cape, a region that supports 12.6% of the country's population.10 The area faces a disproportionate burden of acute injuries and illnesses with high rates of HIV and tuberculosis.7 It is also one of SA's poorest provinces and is a key priority area for HIV research and capacity building.7 Both hospitals are affiliated with the Walter Sisulu University. Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital is a large tertiary-care referral centre with 24-h trauma services, seeing only patients requiring specialty or surgical interventions referred from other district-level facilities. Mthatha Regional Hospital is a district-level facility that provides care to walk-in patients and referrals from adjacent maternal and childcare facilities. The EDs provide 24-h coverage and see 100-150 patients daily from the surrounding 100-km catchment area. Both sites are relatively low-resourced and not equipped with an electronic medical record (EMR) system, patient tracking system or standardised triage processes. Furthermore, there are no providers specialising in emergency medicine at these sites.

Study population

Patients presenting to the ED who were aged 18 years and older and clinically stable (defined as the South African Triage Scale designation of 'non-emergent') were included in the study. Triage scores were assigned by trained study staff, based on the South African Triage Scale (SATS).17 Patients younger than 18 years, not able to provide informed consent (i.e. patients with a depressed level of consciousness or mentally altered) or undergoing active resuscitation were excluded.

Recruitment and sampling

All patients presenting to the ED during the study period who met the inclusion criteria were approached by trained HCT staff, informed of the ongoing study and offered a point-of-care HIV test. Written informed consent was sought for testing and participation in a survey that asked about reasons for accepting or declining the test. Patients with a known HIV-positive diagnosis were asked if they had access to an antiretroviral (ARV) clinic, if they were on regular treatment and whether they were aware of having developed AIDS or being virally suppressed. Data were also collected on patient demographics, presenting complaint, presenting symptoms and past medical history.

HIV counsellors approached all eligible patients in a large waiting room after they underwent initial triage and administrative processes. Patients consenting to the study were escorted to a private room for testing if possible, whereas patients assigned a bed were tested at the bedside with curtains drawn where possible. Given the lack of an EMR or patient tracking system, HCT staff placed a small dot on the folders of all patients who were approached and offered HCT. Every 4 h, the study supervisors audited the folders of patients located within the ED to ensure that all eligible patients had been approached.

Based on recent survey data from the 2017 South African national HIV prevalence study, HIV prevalence amongst South Africans of all ages was estimated at 14%.2 Our study aimed to recruit a sample size of 700 patients at each site. This would present a large enough sample to capture the variation in testing preferences in the study setting, allowing us to detect a difference of greater than 5% from the baseline estimate of 14%, assuming a two-sided α of 0.05 and 80% power, for a period of 7 weeks at each site.

Intervention

Patients were offered point-of-care HIV testing following the South African national HIV testing guidelines.7 Patients who consented to the test provided a blood sample obtained through a lancet finger prick. Following the recommended testing algorithm, patients were first tested using the Advanced Quality Anti-HIV 1&2 rapid test (InTec Products, Inc., Fujian, China). Non-reactive samples were reported as an HIV-negative result. Reactive samples were confirmed with an HIV 1/2/O Tri-line HIV rapid test (ABON Biopharm, Hangzhou, China). Confirmed reactive samples were reported as an HIV-positive result, and patients were provided with a referral letter to a local ARV clinic. Confirmed non-reactive samples were reported as an indeterminate result, and patients were counselled to repeat the test in 4-6 weeks. Counselling preceded and followed all tests and included education on HIV transmission, prevention, and management. Results were available within 10-15 min of testing, whereas counselling required an additional 10-15 min, depending on the HIV test result.

Data collection

Ten local research assistants were hired and trained in rapid point-of-care HCT, good clinical practice and data collection, and were familiarised with the study protocol before the start of the study. Research assistants and study staff worked in shifts to ensure 24-h coverage of the ED.

In tandem with offering HIV testing, HCT staff administered a brief survey. Patient responses to questions about their gender, past medical history, mode of arrival, reason for visit, presenting complaint, and symptoms were recorded as pre-determined binary or categorical options, age was recorded as free text, and reasons for accepting or declining testing were captured via pre-determined categorical options derived from the literature or as free text. Data were recorded on case report forms. These forms were scanned and uploaded onto iDatafax (DF/Net Research, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) by trained study staff. Following validation and cleaning, data were exported into Excel v.16.9 (Microsoft, Inc., Redmond, WA, USA), and then imported into Stata v.14 (StataCorp, TX, USA) for analysis.

The outcome of interest, declining HCT, was measured as a binary variable ('no' = 0 and 'yes' = 1). The independent variables measured were age (18-30, 31-50, 51-70, 70+), sex (male, female), presenting complaint (trauma, medical), South African triage score (death, routine visit, urgent, very urgent, emergent), access to primary care (yes, no), past medical history (hypertension, coronary artery disease, tuberculosis, diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, cancer), visit time (within regular operating hours, 9 am to 5 pm, or out of regular operating hours), visit reason (new complaint, return visit, referral), mode of transport (self-transport, ambulance, police), presenting symptoms (pain, fever) and disposition (death, intensive care unit admission, general admission, emergent surgery, transfer, discharge, absconded).

Data analysis and statistics

Analysis was conducted on patients unaware of their status, to examine the relationship between the outcome of interest and all other independent variables. Chi-square tests were used to explore individual variable associations with declining HCT. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the contribution of each variable to declining HCT. Bivariate analysis was conducted to estimate the association between the outcome and each predictor variable, as well as multivariate analysis to estimate the independent effect of each predictor variable, adjusting for all others. All variables were included in the final model, following checks for collinearity and goodness of fit and performing a best-subsets variable selection. Sub-group analysis was completed on the top reasons for accepting and declining HCT by gender.

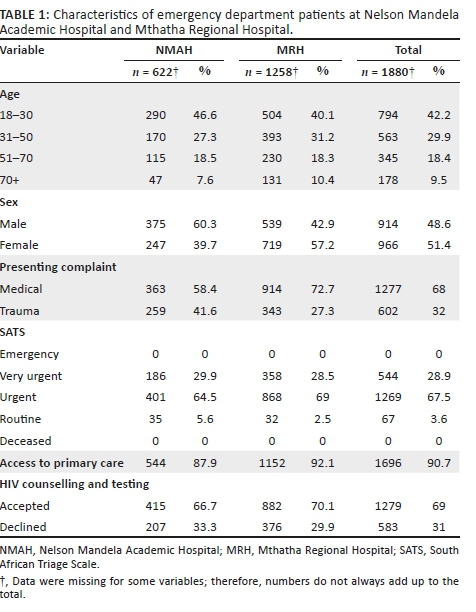

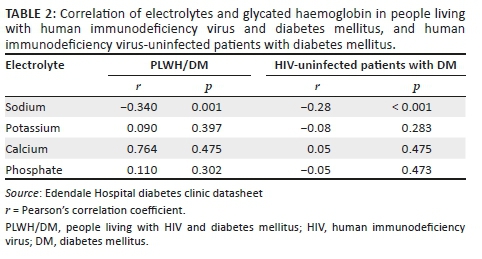

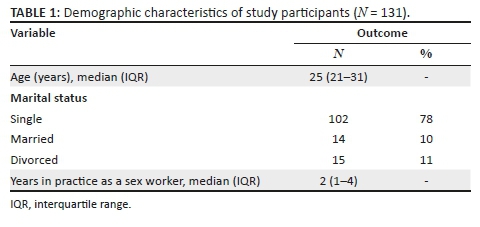

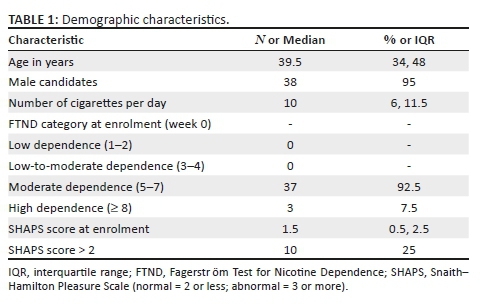

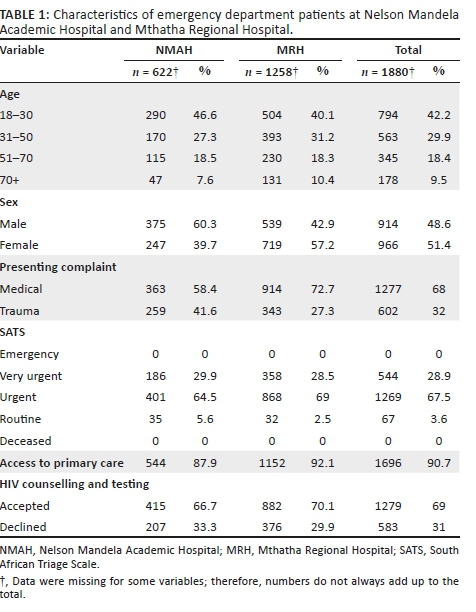

A reference level was selected for categorical variables with multiple responses, and other levels were accordingly compared. Associations were assessed using odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. A pooled analysis of data collected from both sites is presented; no significant differences were observed between the two sites (Table 1).

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (reference number IRB00105801), the Human Research Ethics Committee from the University of Cape Town (MREC reference number 856/2015), the Human Research Committee of Walter Sisulu University (reference number 069/2015) and the Eastern Cape Department of Health. Written consent was obtained from all participants who enrolled in the study and was required for the collection of demographic data, HCT and a follow-up call for newly diagnosed patients, separately.

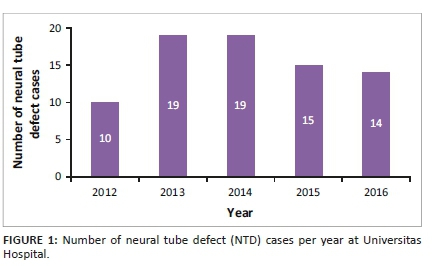

Results

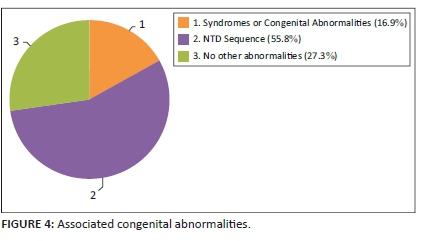

A total of 1010 patients presented to the NMAH ED between 27 June and 13 August 2017. Of these, 727 (72%) patients were approached by HCT staff, and 622 (61.6%) were enrolled in the study. A total of 3245 patients presented to the MRH ED between 24 July and 03 September 2017; of these, 1347 (41.5%) patients were approached by HCT staff, and 1258 (38.8%) were enrolled in the study (Table 1).

Across both sites, 2074 patients were approached by the HCT staff, and 1880 (90.6%) were enrolled in the study. Patients enrolled were slightly female predominant (966, 51.4%), with a median age of 33 years (interquartile range [IQR]:24-59). Most patients presented with medical complaints (1278, 67.9%), received a triage designation of 'urgent' (1269, 67.5%) and reported having access to primary care services (1696, 90.2%; Table 1).

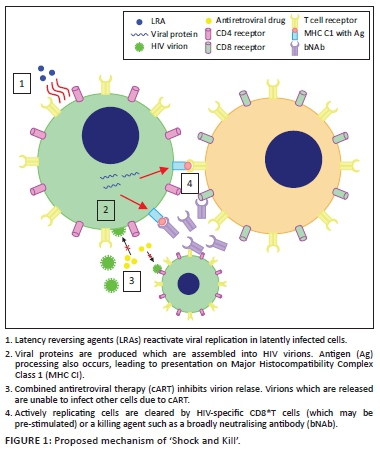

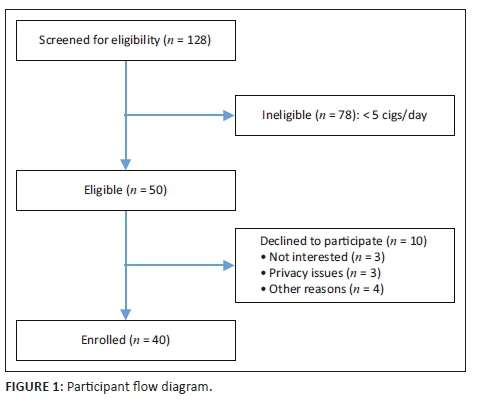

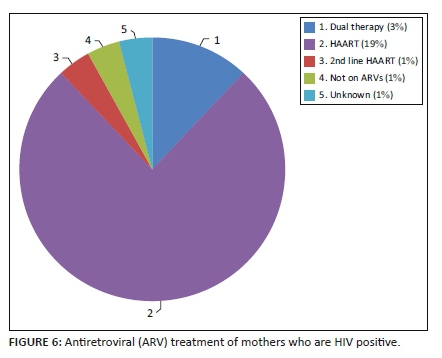

Of the 1880 patients enrolled, 465 (24.7%) patients were aware of their HIV status (defined as a known HIV-positive diagnosis [371, 19.7%] or tested HIV negative within the last 12 months [94, 5%]), and 1415 (75.3%) patients were unaware of their HIV status. Of patients with a known HIV-positive diagnosis, 351 (94.9%) said they were regularly accessing an ARV clinic. Of patients who were regularly accessing an ARV clinic, 23 (6.5%) reported being virally suppressed, 46 (13.1%) reported not being virally suppressed and 282 (80.3%) were unsure (Figure 1). In addition, 20 (5.4%) patients who had a known HIV-positive diagnosis wanted to get retested to confirm if they were truly/still HIV positive.

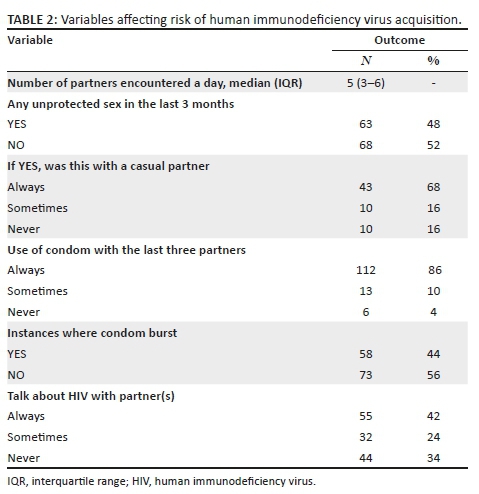

Of the 1415 patients unaware of their status, 141 (10%) declined HCT, and 1274 (90%) accepted. Of the patients who accepted HCT, 159 (12.5%) were diagnosed as HIV positive, 1102 (86.5%) were diagnosed as HIV negative and 13 (1%) had an indeterminate result. The overall prevalence of HIV in the study population was 28.1%. Patients declining and those accepting HCT both largely presented with medical complaints (912, 64.5%), received a triage designation of 'urgent' (954, 67.4%), had stated access to primary care services (1255, 89.2%), had no past medical history (929, 65.7%), visited the ED outside of regular hours (799, 56.5%), had a new complaint (878, 62.4%), used self-transport (881, 62.7%), had symptoms of pain (790, 55.8%), had no symptoms of fever (1388, 98.1%), were ultimately discharged from the ED (718, 53.9%) and were aged 18-30 years (629, 44.5%; Table 2).

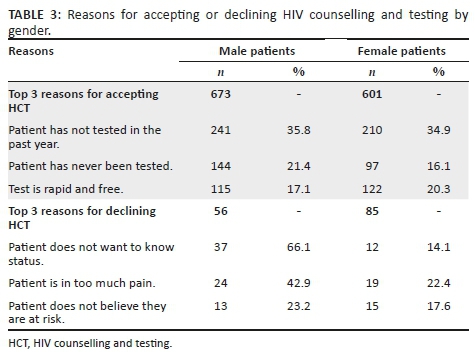

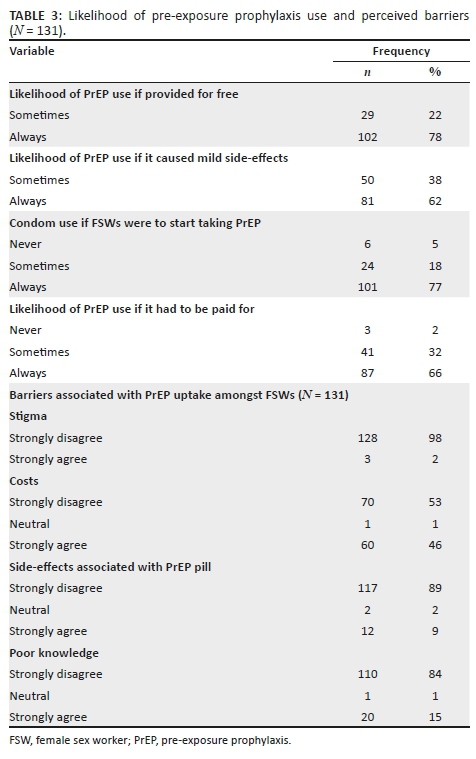

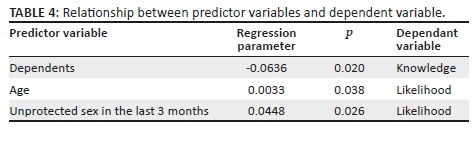

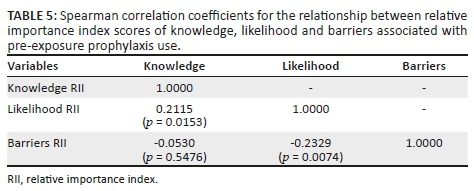

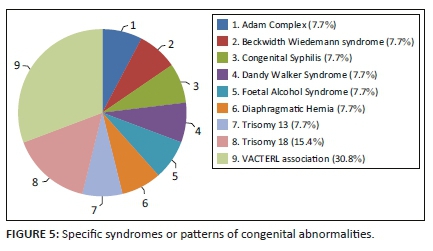

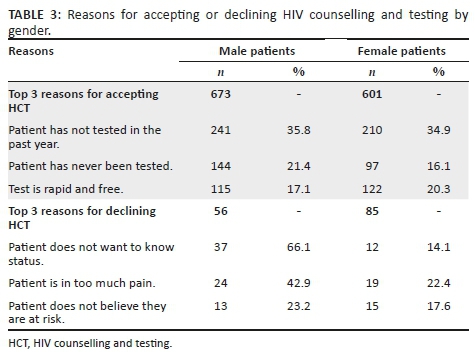

The top reasons for accepting HCT were 'has not tested in the past year' (451, 35.4%), 'has never been tested' (242, 18.9%) and 'test is rapid and free' (237, 18.6%) (Figure 1). Patients accepting testing were largely male (672, 52.7%). The top reasons for declining HCT were 'does not want to know status' (53, 37.6%), 'in too much pain' (48, 34%) and 'does not believe they are at risk' (28, 19.9%; Figure 1). Patients declining testing were largely female (85, 60.3%).

Sub-group analysis of the reasons for accepting and declining HCT by gender showed slight differences between men and women in the reported reasons (Table 3). The primary reason for accepting HCT for both men and women was 'has not tested in the past year', 35.8% and 34.9%, respectively, followed by 'has never been tested' (21.4%) for men and 'test is rapid and free' (20.3%) for women. The primary reason for declining HCT given by men was 'does not want to know status' (66.1%) and 'in too much pain' for women (22.4%), followed by 'in too much pain' for men (42.9%) and 'does not believe they are at risk' (17.6%) for women.

Univariate analysis showed that compared with male patients, female patients were more likely to decline HCT Associations were assessed using odds ratio (OR: 1.7; 95%) Confidence Intervals (CI:1.2-2.4). Patients who complained of pain compared with patients who did not (OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.2-2.5) and those arriving at the ED by ambulance compared to self-transport or with the police (OR: 1.4; 95% CI: 1.1-2.1) were also more likely to decline HCT. In addition, patients presenting with traumatic injuries compared with medical complaints (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.1-2.2) were more likely to decline HCT. Other factors including age, triage score, access to primary care, past medical history, visit time, visit reason and final disposition did not show a statistically significant correlation with declining HCT (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis showed that patients who complained of pain compared with patients who did not (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.1-2.6) were slightly more likely to decline HCT. Other variables did not show a statistically significant correlation with declining HCT (Table 2).

Discussion

We found acceptance of HCT services in the ED to be reassuringly high. Our study revealed that 90% of patients who were unaware of their HIV status accepted HIV testing. This was observed despite patients being in a clinical environment where HIV testing is not routinely offered and where patients present with acute injury or illness and are often in pain or moderate distress.11,18 These findings are consistent with results from other LMICs. In Kenya and Guyana, it was found that 97.7% and 75.5% of non-critical patients accepted HCT in the ED, respectively.19,20 Our results also highlight a substantial burden of undiagnosed HIV: 8.5% of enrolled patients were newly diagnosed as HIV positive. These patients presented to the ED for various clinical complaints, and a positive diagnosis of HIV was an incidental finding.

The two most common reasons for accepting HCT in the ED were 'has not tested in the past year', followed by 'has never been tested'. This positively implies the need for HCT in acute care settings, to cover the existing testing gap, as we are able to capture patients who are currently missed by other testing venues within the healthcare system. Recently, novel approaches for HCT - such as home-based, community-based and couples testing - have been added to traditional facility-based HCT delivery systems, with good acceptance rates.21,22 A systematic review of HCT strategies in sub-Saharan Africa reported an acceptance rate of 70% for home-based testing and 76% for community-based testing.21 However, despite the variety of testing strategies and venues, a testing gap remains, particularly amongst young adults and men.23,24 Considering that 44.1% of all patients accepting testing were young adults (18-30 years) and 52.7% were male, our study demonstrates that the ED is an opportune venue to capture this missed population.

Another factor leading to testing acceptance, reported by a fifth of patients accepting HCT, was 'the test is rapid and free'. This measure combines both cost and ease/limited time lost to testing. While it is hard to separate the two and determine which is a more significant factor, ensuring that both are addressed is a likely key to maintaining high acceptance of HCT in a fast-moving environment such as the ED. This is supported by a study in Uganda, where 25% of ED patients reported not knowing their HIV status because of the lack of access to free testing services.16 At present, HCT services are offered free of cost in all government healthcare facilities in SA; however, maintaining free services can be burdensome for the government, especially if testing services are to be further expanded. Furthermore, ensuring that testing and counselling are not time-consuming and are part of routine clinical care in the ED might address the barrier of having to seek out testing as a discrete task in itself.

Acceptance, however, was not universal. In our study population, women were significantly more likely to decline to test, whereas men were more likely to accept. Similar findings were observed in other studies examining the acceptability of testing in EDs, in both high- and low-resource settings.20,25 This might be because women are aware of having access to testing services during antenatal visits, through preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programmes or through family planning services, and hence do not need to test in the ED.1 This is supported by the finding that more women were already aware of their HIV status; 71.6% of the patients with a known HIV-positive diagnosis were women. In addition, a significant proportion of women presenting to the ED in our context were diagnosed with pregnancy complications or injury wounds, likely justifying 'in too much pain' as the primary reason reported for women to decline HCT. On the contrary, though women were more likely to decline HCT, a majority still accepted testing when offered. While it is difficult to generalise individual motivations, factors including lack of social support and fear of stigma or rejection if tested HIV positive, especially in the presence of their partner or family accompanying them to the ED, may otherwise underlie the greater tendency of women to decline HCT.25

The top reasons reported for declining HCT in our ED, 'does not want to know status' and 'does not believe they are at risk', are interestingly established findings from high-income countries and LMICs, across healthcare settings.16,20,26,27,28,29 It could be that patients prefer uncertainty rather than facing the psychosocial consequences of an HIV-positive diagnosis, especially considering the imaginable stigma attached to such a diagnosis.30 This could be tackled through targeted pre- and post-counselling efforts. On the contrary, it is also possible that the small proportion of patients who declined to be tested are not at risk of contracting HIV and were accurately perceiving their risk. We did not include any risk measures in our survey and are thus unable to precisely indicate individuals who should have been tested.

A significant barrier to HCT in the ED and other healthcare facilities frequently described in the literature are stigma and the lack of confidentiality.20,26,31 This finding is supported by contextual knowledge, wherein anthropological studies exploring cultural perceptions and practices around HIV in Mthatha have reported pervasive stigma attached to HIV/AIDS, resulting in multiple forms of exclusion based on sexism, racism and homophobia,30 The National HIV Prevalence Survey indicated that 26% of people would not be willing to share a meal, 18% were unwilling to sleep in the same room and 6% would not speak to PLWH.2 Yet, none of the patients declining testing in our study reported reasons implying real or perceived stigma or the lack of confidentiality. The studies supporting this notion conducted in-depth interviews or had one-on-one conversations with patients, which likely allowed for deeper exploration of patient perspectives on HCT services, whereas given the patient volumes, high turnover and the lack of any coordinated processes in our study setting, it is possible that patients were less likely to report stigma as a reason for declining testing.

Pain was a notable justification for declining testing in this context and showed significant correlation through bivariate and multivariate analysis. The second most common reported reason, 'in too much pain', was not surprising, as a high proportion of cases presented with acute traumatic injuries. In addition, traumatic injuries and arriving at the ED in an ambulance, which are critical proxies to pain and the seriousness of a patient's condition, were positively correlated with declining testing. This finding is specific to declining HCT in the ED and has not been previously reported as a barrier in other testing venues. To address this barrier, the integration of pain management before HCT is recommended. If a patient's presenting complaint has been addressed by providers, and appropriate action taken, patients might be more likely to accept testing.

Linkage to care is the next critical step following testing. As part of our study, all newly diagnosed patients were counselled extensively on the importance of seeking follow-up care and were given a referral letter. Given that both NMAH and MRH see patients from a 100-km radius, it was challenging to ensure linkage to care, as it would depend on the area individuals came from and the presence and ease of access to an ART clinic. For patients who were local to Mthatha, we were able to direct them to the Gateway Clinic - an ART centre - located within the same campus as the hospital. With the consent of all patients who were newly diagnosed as HIV positive, we collected their names and contact details to conduct follow-up calls after 1 month, 6 months and a year. The follow-up calls will allow us to assess whether individuals have been able to link to care and/or what challenges they are facing in doing so. Results from the follow-up calls will be collated and analysed post-completion. Despite these challenges, 94.9% of patients with a known HIV-positive diagnosis presenting to the EDs reported having access to an ART clinic, and 85.4% of those individuals reported regularly accessing the clinic. These rates are commendable and imply a willingness of patients in this setting to seek follow-up care. However, these are self-reported statistics and could be inflated as a result of social-desirability bias.

Another interesting finding was that a small proportion of patients with a known HIV-positive diagnosis (20, 5.4%) requested a repeat test to confirm their diagnosis. Patients stated that they wanted to confirm whether they were truly HIV positive and/or if they were still HIV positive. Upon retesting, all 20 patients were HIV positive. The desire to retest when an opportunity presented could likely be a result of mistrust in the healthcare system or a result of the low health literacy in the region, which are both potential barriers to achieving high rates of testing and sustained linkage to care.30,31

There are several study limitations to consider. The protocol was to approach every patient presenting in the ED who met the inclusion criteria. However, the lack of infrastructure, systematic medical record-keeping or a patient tracking process made it challenging to retain all patients who presented to the ED. Many patients were missing from the records, whereas others were entered multiple times, making it difficult to keep count of the total number of patients. HIV counselling and testing services were provided 24 h a day, yet we were only able to approach 48% of patients who presented for care. We believe this is, in part, a result of the high volumes of patients and the quick turnaround time, as well as the time-consuming nature of counselling. Patients enrolled in the study may be a biased subset of the ED population, namely, easier to approach, spoke the same language as the HCT counsellors, had milder injuries or conditions and presented at times when the patient volume was lower. Maintaining confidentiality was challenging given the limited space - the EDs in both hospitals were in essence one big room, with beds lined up against each other. Lastly, the study was human-resource intensive. We had a team of four dedicated HCT staff at all times. Nevertheless, greater staff numbers would have allowed the capture of more study subjects. Such a situation would be difficult to sustain in a low-resource setting such as Mthatha.

To optimise our strategy and accurately capture data, given the lack of organisation and clear processes, our data were collected prospectively, whereby we relied less on recorded data and were able to capture most of it in real time. As the ED is busy and sees high patient volumes, we attempted to collect as much data as efficiently as possible, using a survey format with mostly 'yes' and 'no' questions. However, to have had a better understanding of patient perspectives, the study might have been enhanced by in-depth telephone interviews with a smaller number of patients after they had left the ED.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated high patient acceptance of the nationally recommended HCT strategy in an ED setting. The overall adult prevalence of HIV in the ED was high at 28.1%. Patients who were male, young and not in pain or critically injured were more likely to accept HCT, critically supporting the provision of HCT in acute care settings, as it successfully captured an important demographic that has generally been missed through other testing venues. In addition, the lack of significant correlation in demographic or clinical characteristics and HCT uptake argues for a routine, non-targeted strategy in the ED. Our study further reveals the need for continued investment to ensure that HCT is widely available, with provision to effectively identify and manage pain and trauma. Finally, critical to embedding HCT in the routine clinical care offered in the ED will be the confidential conduct of HCT that permits stigma around HIV infection and testing to be appropriately addressed - something that will require further innovation and implementation research.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the staff in the Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital and Mthatha Regional Hospital emergency departments for making this research possible and the HIV Counselling and Testing team for their dedication and hard work during the study. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of Nomzamo Mvandaba for her assistance as a study coordinator for the WISE study and those of Victoria Chen and Kathryn Clark in data collection and data validation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

B.H. conceived the original idea for the parent study and designed the protocol. A.R., P.M. and B.H. coordinated the study and data collection. A.R. carried out data analysis and prepared the manuscript. C.K., T.C.Q., D.S. and B.H. provided substantial edits and revisions.

Funding information

This research was supported by the South African Medical Research Council, the Division of Intramural Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, A.R. The data are not publicly available because they contain sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclaimer

All views expressed in the submitted article are the authors' own and not an official position of the institutions represented or the funders.

References

1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2019. UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland; 2019. [ Links ]

2.Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Zungu N, et al. South African National HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour, and communication survey, 2017. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press; 2019. [ Links ]

3.UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. [ Links ]

4.UNAIDS. Ending AIDS: Progress towards the 90-90-90 targets. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2017. [ Links ]

5.Johnson LF, Chiu C, Myer L, et al. Prospects for HIV control in South Africa: A model-based analysis. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):30314. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.30314 [ Links ]

6.DoHRoS A. National HIV counselling and testing (HCT) policy guidelines 2015. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2015. [ Links ]

7.SANAC. Let our actions count: South Africa's National strategic plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017-2022. Pretoria: SANAC; 2017. [ Links ]

8.Telisinghe L, Charalambous S, Topp SM, et al. HIV and tuberculosis in prisons in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2016;388(10050):1215-1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30578-5 [ Links ]

9.Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: A review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):355-366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X [ Links ]

10.DoHRoS A. Mid-year population estimates. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2015. [ Links ]

11.Rothman RE, Ketlogetswe KS, Dolan T, Wyer PC, Kelen GD. Preventive care in the emergency department: Should emergency departments conduct routine HIV screening? A systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(3):278-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb02004.x [ Links ]

12.Hsieh YH, Kelen GD, Beck KJ, et al. Evaluation of hidden HIV infections in an urban ED with a rapid HIV screening program. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):180-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.10.002 [ Links ]

13.Kelen GD, Shahan JB, Quinn TC. Emergency department-based HIV screening and counseling: Experience with rapid and standard serologic testing. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(2):147-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70387-2 [ Links ]

14.Haukoos JS, Rowan SE. Screening for HIV infection. BMJ. 2016;532(1):i1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1 [ Links ]

15.Curry C, Bunungam P, Annerud C, Babona D. HIV antibody seroprevalence in the emergency department at Port Moresby General Hospital, Papua New Guinea. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(4):359-362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2005.00757.x [ Links ]

16.Nakanjako D, Kamya M, Daniel K, et al. Acceptance of routine testing for HIV among adult patients at the medical emergency unit at a national referral hospital in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5):753-758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-006-9180-9 [ Links ]

17.Twomey M, Wallis LA, Thompson ML, Myers JE. The South African Triage Scale (adult version) provides reliable acuity ratings. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(3):142-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2011.08.002 [ Links ]

18.Hansoti B, Kelen GD, Quinn TC, et al. A systematic review of emergency department based HIV testing and linkage to care initiatives in low resource settings. PLoS One. 2017;12(11). e0187443. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187443 [ Links ]

19.Waxman MJ, Muganda P, Carter EJ, Ongaro N. The role of emergency department HIV care in resource-poor settings: Lessons learned in western Kenya. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1(4):317-320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12245-008-0065-8 [ Links ]

20.Christensen A, Russ S, Rambaran N, Wright SW. Patient perspectives on opt-out HIV screening in a Guyanese emergency department. Int Health. 2012;4(3):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inhe.2012.03.001 [ Links ]

21.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528(7580):S77-S85. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16044 [ Links ]

22.Jurgensen M, Sandoy IF, Michelo C, Fylkesnes K, Group ZS. Effects of home-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV-related stigma: Findings from a cluster-randomized trial in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;81(1):18-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.011 [ Links ]

23.Nglazi MD, Van Schaik N, Kranzer K, Lawn SD, Wood R, Bekker LG. An incentivized HIV counseling and testing program targeting hard-to-reach unemployed men in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):e28-e34. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824445f0 [ Links ]

24.Johnson LF, Rehle TM, Jooste S, Bekker LG. Rates of HIV testing and diagnosis in South Africa: Successes and challenges. AIDS. 2015;29(11):1401-1409. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000721 [ Links ]

25.Pisculli ML, Reichmann WM, Losina E, et al. Factors associated with refusal of rapid HIV testing in an emergency department. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):734-742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9837-2 [ Links ]

26.Chimoyi L, Tshuma N, Muloongo K, Setswe G, Sarfo B, Nyasulu PS. HIV-related knowledge, perceptions, attitudes, and utilisation of HIV counselling and testing: A venue-based intercept commuter population survey in the inner city of Johannesburg, South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):26950. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26950 [ Links ]

27.Schechter-Perkins EM, Koppelman E, Mitchell PM, Morgan JR, Kutzen R, Drainoni ML. Characteristics of patients who accept and decline ED rapid HIV testing. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(9):1109-1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.05.034 [ Links ]

28.Christopoulos KA, Weiser SD, Koester KA, et al. Understanding patient acceptance and refusal of HIV testing in the emergency department. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-3 [ Links ]

29.Gazimbi MM. A multilevel analysis of the determinants of HIV testing in Zimbabwe: Evidence from the demographic and health surveys. HIV/AIDS Res Treat Open J. 2017;4(1):17. http://doi.org/10.17140/HARTOJ-4-124 [ Links ]

30.Leclerc-Madlala S, Simbayi LC, Cloete A. The sociocultural aspects of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. In: HIV/AIDS in South Africa 25 years on: Psychosocial perspectives. 2009; p. 13-25. [ Links ]

31.Nombembe C. Music-making of the Xhosa diasporic community: A focus on the Umguyo tradition in Zimbabwe. Cape Town: University of Witwatersrand, Faculty of Humanities, Wits School of Music in Cape Town; 2013. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Aditi Rao

aditi.rao@jhmi.edu

Received: 15 May 2020

Accepted: 02 June 2020

Published: 22 July 2020

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Retention in care for adolescents who were newly initiated on antiretroviral therapy in the Cape Metropole in South Africa

Brian van Wyk; Ebrahim Kriel; Ferdinand Mukumbang

School of Public Health, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Long-term retention of adolescents aged 10 -19 years on antiretroviral therapy (ART) is crucial to achieve viral load suppression. However, it is reported globally that adolescents have lower retention in care (RiC) on ART, compared with children and adults.

OBJECTIVES: To determine the prevalence and predictors of RiC of adolescents over 2 years following initiation onto ART in public health facilities in the Metropole District Health Services of the Western Cape province in 2013.

METHODS: Data of 220 adolescent patients who were newly initiated on ART in 2013 were extracted from the provincial electronic database, and subjected to univariate and bivariate analyses using SPSS.

RESULTS: The rate of RiC post-initiation was low throughout the study period, that is, 68.6%, 50.5% and 36.4% at 4, 12 and 24 months, respectively. The corresponding post-initiation viral load suppression levels on ART of those remaining in care and who had viral loads monitored were 84.1%, 77.4% and 68.8% at 4, 12 and 24 months, respectively. Retention in care after initiation on ART was higher amongst younger adolescents (10-14 years), compared with older adolescents (15-19 years). Male adolescents were significantly more likely to be retained, compared with females. Pregnant adolescents were significantly less likely to be retained compared with those who were not pregnant.

CONCLUSION: Key interventions are needed to motivate adolescents to remain in care, and to adhere to their treatment regimen to achieve the target of 90% viral load suppression, with specific emphasis on older and pregnant adolescents.

Keywords: HIV; AIDS; adolescents; youth; retention in care.

Introduction

Globally, it has been estimated that 190 000 (59 000-380 000) adolescents, between the ages of 10 and 19 years, were newly infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 2018, and the total number of adolescents living with HIV (ALWH) was 1.6 million (1.1-2.3 million), which accounts for 4% of all people living with HIV (PLWH).1 Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest number of HIV-infected adolescents with about 1.5 million of them. In South Africa (SA), it is estimated that 280 000 children aged between 0 and 14 years were living with HIV in 2017, and that just under 7 million persons aged ≥ 15 years were PLWH.2 The national HIV household survey estimated HIV prevalence in 0-14-year-olds to be 3.0% and 2.4% for females and males, respectively.3 In 15-19-year-olds, it was 5.8% in females and 4.7% in males. The number of adolescents aged 15-19 years receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) in SA increased tenfold between 2005-2008 and 2013-2016.4 This increase is attributed to perinatally infected infants surviving into adolescence and to a rising incidence of HIV in behaviourally infected 15-19-year-olds.

Despite success in ART roll-out in most countries over the last decade, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related deaths amongst adolescents have increased whilst declining in other age groups.5 To prevent AIDS-related deaths, the infected must be diagnosed, receive ART and remain in care to maintain viral load (VL) suppression. This would help achieve the 90-90-90 targets of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS).6 Retention on ART is particularly challenging for key populations, such as adolescents, amongst others, and has been noted as a global priority for action.7,8 Previous studies confirm that adherence, retention in care (RiC) and treatment outcomes for adolescents in southern Africa are worse, compared with adults.9,10,11

However, routine monitoring of HIV treatment programmes does not report RiC and treatment outcomes for adolescents (10-19 years); they report only for children (0-14 years) and adults (15 years and older).11 In this way, adolescent problems with RiC and treatment outcomes remain undetected in the monitoring of HIV programmes. It is argued that because of the general adherence problems faced by adolescents globally, specific analysis is needed to report outcomes for this age group at a health-systems level.8

Objectives

This article reports on the RiC of ALWH aged 10-19 years who were newly initiated on ART in public health facilities in the Western Cape Metropole, SA, in 2013, and the risk factors associated with remaining in care at 4, 12 and 24 months post-initiation on ART.

Methods

Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of adolescents aged 10-19 years, who were initiated on ART in 2013 in the Western Cape Metropole.

Study context

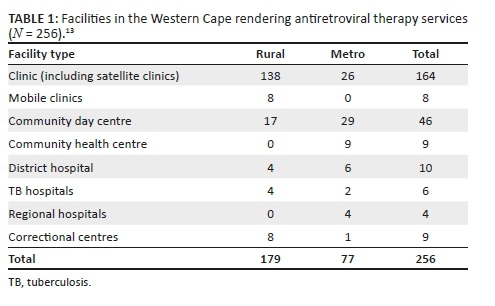

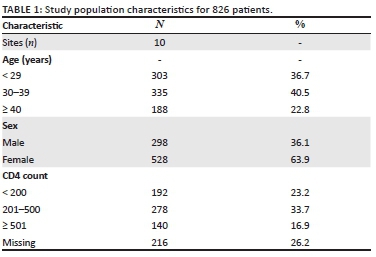

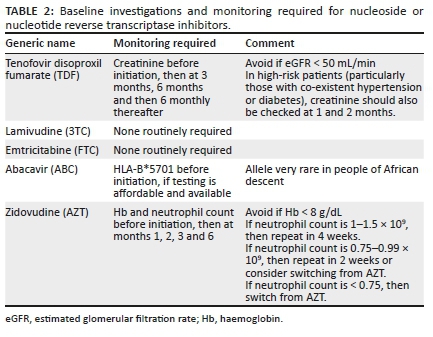

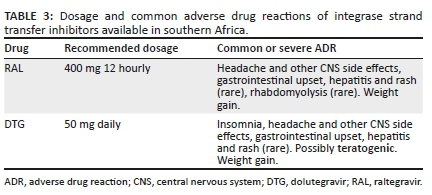

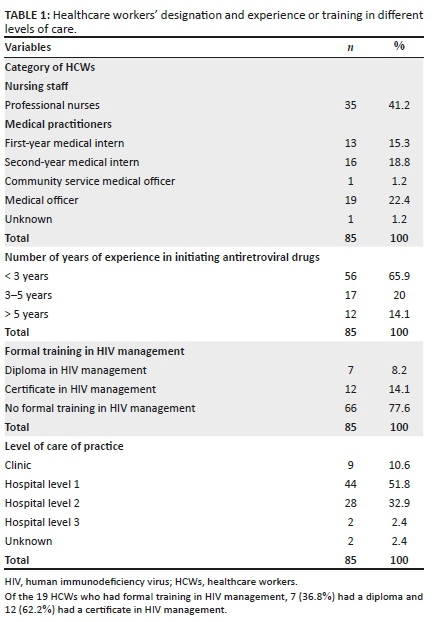

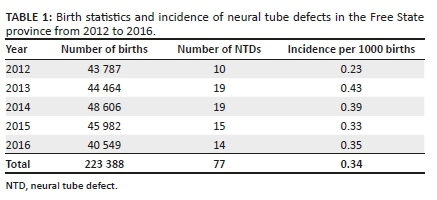

The Western Cape's ART programme has been in existence for over 10 years. The 2013 version of the ART guidelines was updated in 2016, and had consolidated adult, adolescent, paediatric and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV guidelines.12 In the province of the Western Cape, most adults and children access ART services at primary healthcare facilities, such as clinics, community day centres and community health centres. At the end of June 2017, this province had 237 285 patients on ART, of whom 229 171 were aged ≥ 15 years and 8114 were aged < 15 years. The Cape Town Metropole accounts for 74.3% (167 833) of the total number of ART patients in the Western Cape, that is 162 092 aged ≥ 15 years and 5741 aged < 15 years.13 Antiretroviral therapy services are rendered at the various Western Cape facilities, as outlined in Table 1.13

However, services rendered at these facilities vary. Some provide only adult ART services. Others offer both adult and paediatric support. Some facilities offer ART daily, whilst others provide ART only on certain days of the week. Human resource capacity also varies. Not all facilities have resident medical officers or clinical nurse practitioners. Hence, the need for outreach support arises. The capacity to care for adults in the Western Cape has improved with the implementation of the nurse-initiated management of antiretroviral treatment (NIMART) programme, whereby nurses are trained and receive structured mentorship and accreditation to initiate first-line ART. A challenge in the rural areas is the irregular access to competent and skilled clinicians to manage paediatric patients and complicated adult and adolescent patients. As previously stated, most ART services are designated as paediatric or adult. Adolescent-specific ART services are not yet part of standard care being offered at all ART facilities. Those that do are limited to services initiated and/or supported by tertiary hospitals or non-profit organisations.

Data source

Two data sources were used for this analysis: the Three Interlinked Electronic Registers.Net (TIER.Net),14 an electronic ART database developed by the University of Cape Town's Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Research, and patients' folders accessed at the treating facilities. Tier.Net is used operationally in the public health facilities of SA to monitor baseline clinical care and client outcomes over time. It is also the platform on which HIV tests are electronically captured in the public sector.15

We first visited the Tier.net platform to obtain data on all those who met the inclusion criteria. With the use of our data-capturing form, we searched for the relevant information from the Tier.net platform. Where information was missing, we accessed the patient's folder to confirm the availability of the required information.

Study participants

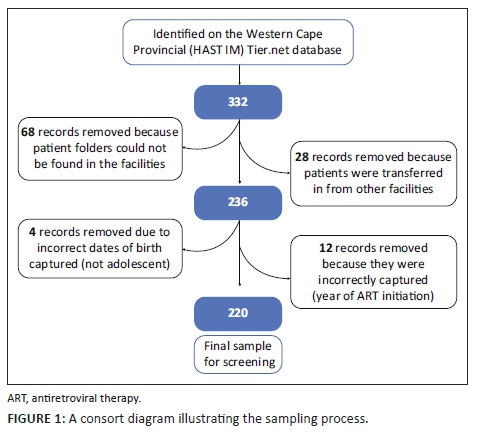

Data were found for 332 ALWH newly registered on ART from 29 facilities across the Western Cape Metropole and extracted from the provincial Tier.net register. Only 220 participants were included in the final analysis. Of the 112 excluded, for 68, folders could not be found in spite of making numerous attempts to trace these documents at the various facilities. Furthermore, 28 patients were incorrectly captured as new patients when they had been transferred in from other facilities; 4 patients were not adolescents, and their birth dates had been incorrectly captured; and 12 patients had been incorrectly captured as having initiated ART in 2013.

Main outcome measures and analysis

We extracted data on sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, source of income, type of dwelling, disclosure to significant other and reported alcohol or other drug use) and clinical characteristics (CD4 count, WHO stage, pregnancy and ART regimen).

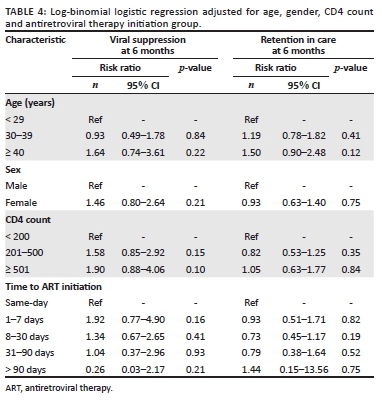

Bivariate analysis was conducted to determine the significance and strength of association between RiC at 4, 12 and 24 months and various sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Statistical significance was tested by using the chi-square test, with significance set at p < 0.05, and where significant, the strength of association was calculated as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI), using SPSS v23. Our use of 4, 12 and 24 months rather than 6, 12 and 24 months is informed by the operational guidelines of the Western Cape's ART programme, which requires the first VL test to be conducted at 4 months and the patient to return for results in month 5.16 Patients would receive 1 month's medication if they have unsuppressed VL, and 2 months' supply if their VL is suppressed. The reason for the 4-month RiC measurement is to identify how many ALWH return for their VL tests. The subsequent RiC behaviour of the patients is measured annually.

Survival analysis was assessed with lost to follow-up (LTFU) as the outcome of interest. We did a comparative survival analysis for the age and sex of the study participants. We reported the hazard ratios and p-values. An ALWH was considered LTFU if they had not made contact with a treating healthcare facility within 90 days since their last registered contact for HIV-related treatment and care. The LTFU date was determined from the day when the patient was last seen at the clinic where they were provided with their last medication. Therefore, by using the intention-to-treat population in this study, the RiC definition was the proportion of HIV-infected adolescents alive and on ART at months 4, 12 and 24 in the entire study sample.

Ethical consideration

The protocol was approved by the University of the Western Cape Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: BM/17/1/15) and the Government Health Impact Assessment (Reference number: WC_2017RP58_418) Committee.

Results

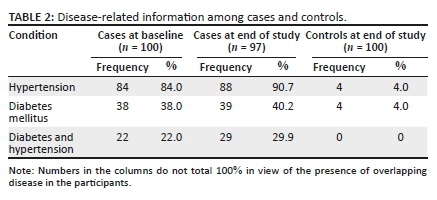

Of the 220 adolescents who were newly initiated on ART in 2013, the majority were 'older' adolescents, 15-19 years (n = 179, 81.4%) and female (n = 182, 82.7%) (Table 2). Most were financially supported by their families and friends (n = 129, 58.6%) and lived in a formal house (n = 116, 52.7%). As per HIV clinical treatment guidelines, the overwhelming majority (n = 182, 87%) had disclosed their HIV status to a significant other.

The median CD4 count at ART initiation was 292.5 cells/mm3 (interquartile range [IQR]: 228.8-391.3). Only two participants had no baseline CD4 count recorded. Half of the participants (n = 109) were initiated with a CD4 count between 200 cells/mm3 and 349 cells/mm3, and 19% (n = 42) had a baseline CD4 count of < 200 cells/mm3 as per the HIV treatment guidelines of 2013.

Of the 213 participants who had WHO staging done at ART initiation, 46.5% and 22.5% were WHO stages I and II, respectively, and 23.2% and 6.8% were WHO stages III and IV, respectively. As with the CD4 counts, clinical staging is taken into consideration in the universal test and treat era.

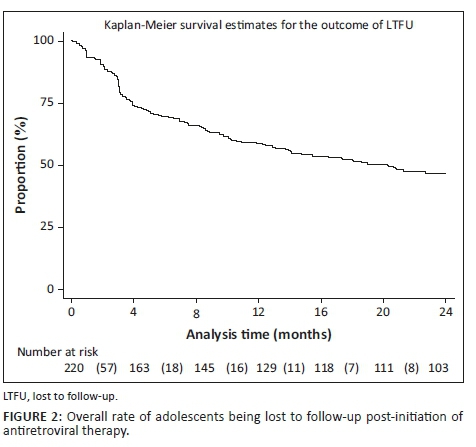

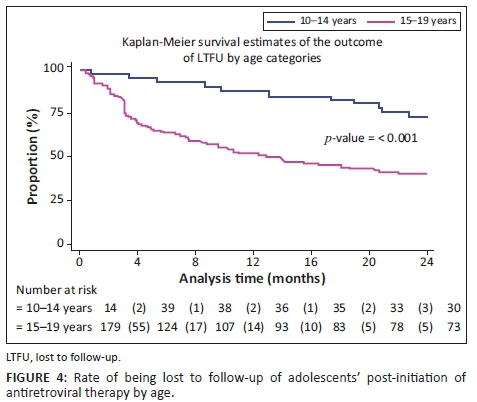

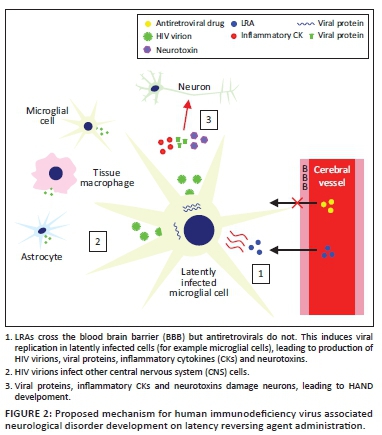

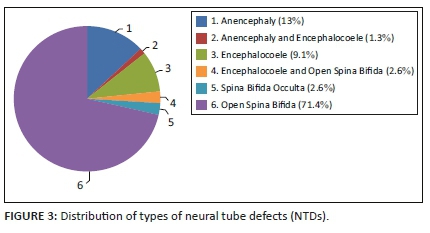

Observed RiC was low throughout the study period with 68.6%, 50.5% and 36.4% adolescents being retained in care at 4, 12 and 24 months post-initiation on ART, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of RiC at 4, 12 and 24 months between younger (10-14 years of age) and older (15-19 years of age) adolescents (90.2% vs. 63.7%, 82.9% vs. 43.0% and 68.3% vs. 29.1%, respectively). However, RiC of the younger adolescents at month 4 was just over 90%, but the younger adolescents at months 12 and 24 fell short of 90%. The older adolescents showed poorer rates of RiC at months 4, 12 and 24, compared with the younger adolescents at the same time periods.

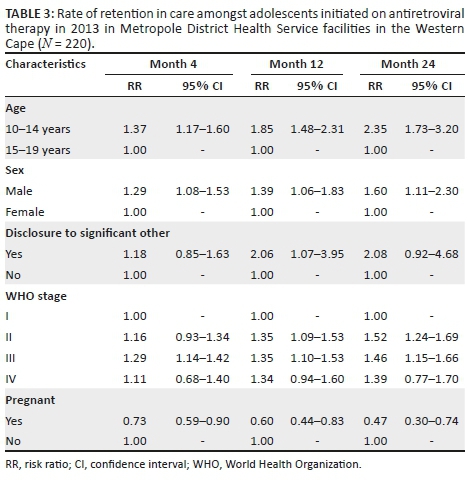

Table 3 shows that a significantly higher number of younger adolescents (10-14 years) were retained in care at 4, 12 and 24 months post-initiation on ART, compared with older adolescents (15-19 years). At 4 months post-initiation on ART, younger adolescents had 37% higher risk (likelihood) of RiC (RR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.17-1.60) compared with older adolescents. At 12 months post-initiation on ART, younger adolescents had 85% higher risk of RiC (RR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.48-2.31), compared with older adolescents, and more than two times higher risk (RR = 2.35, 95% CI: 1.73-3.20) at 24 months.

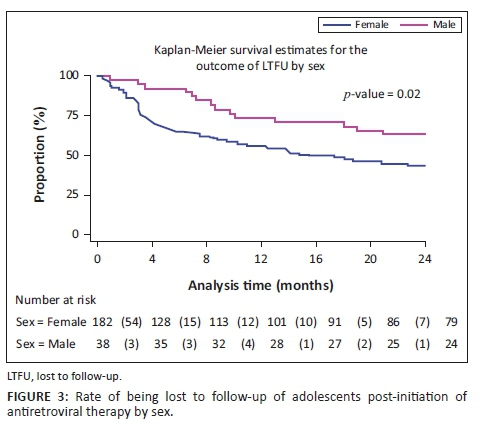

Male adolescents had higher rates of RiC post-initiation of ART at 4 months (RR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.08-1.53), 12 months (RR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.06-1.83) and 24 months (RR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.11-2.30), compared with female adolescents.

Adolescents who were pregnant had significantly lower rates of RiC post-initiation of ART, compared with all other adolescents at 4 months (RR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.59-0.90), 12 months (RR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.44-0.83) and 24 months (RR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.30-0.74).

Adolescents who disclosed their HIV status to a significant other were two times more likely to be retained in care at month 12 (RR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.07-3.95) than adolescents who did not disclose to a significant other.

Adolescents classified as WHO stage I at ART initiation had significantly lower rates of RiC at 4 months post-initiation, compared with adolescents who were classified as WHO stage III (RR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.14-1.42). Those classified as WHO stages II and IV also had better rates of RiC at month 4, compared with adolescents classified as WHO stage I at baseline, but these did not reach statistical significance. At 12 months post-initiation of ART, those who were at WHO stage II (RR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.09-1.53) as well as WHO stage III (RR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.10-1.53) at baseline had a 35% greater risk (likelihood) of RiC, compared with those who were WHO stage I at ART initiation. Adolescents who were at WHO stage I at baseline also showed significantly lower RiC rates at 24 months post-initiation of ART, compared with those who were at WHO stage II (RR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.24-1.69) and WHO stage III (RR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.15-1.66) at baseline. At 24 months post-initiation of ART, adolescents who were classified as WHO stage II (RR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.09-1.53) and those who were WHO stage III (RR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.10-1.53) at ART initiation had a 35% greater risk of RiC, compared with those who were WHO stage I at ART initiation. Those adolescents who were classified as WHO stage IV at ART initiation showed better RiC rates at months 4, 12 and 24 post-initiation, but none of these reached statistical significance.

Figures 2, 3 and 4 show the survival curves of the study participants. The overall person-time at risk of being LTFU was 3303 months, with an incidence of 119/3807 (4/100) person-months. The hazard ratio for males compared with females was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.41-1.26). The hazard ratio for those aged 15-19 years compared with those aged 10-14 years was 2.53 (95% CI: 1.30-4.91).

Discussion

In 2014, the UNAIDS set a global ART target of 90-90-90. This includes the goal that 90% of persons who test HIV-positive should be initiated on ART.6 Having successfully tested and initiated ALWH onto ART, their RiC and the maintenance of VL suppression of at least 90% are the ongoing challenges. Our study reports that the overall RiC of ALWH was low throughout the 24-month observation period. Contrary to our findings, Nabukeera-Barungi et al. found that 90.4% of Ugandan adolescents demonstrated good RiC with an LTFU of only 5%.17 A meta-analysis of six South African studies also reported a relatively high ALWH retention rate of 83% (95% CI: 68% - 94%) in the first 2 years on ART.18 The results of our study are reported with the intention-to-treat population as the denominator at every time point, that is, months 4, 12 and 24, and without the exclusion of transfer-outs, LTFU patients and the numerator being those alive and on ART. The above-mentioned studies did not measure RiC in the same manner. Nabukeera-Barungi et al.17 determined RiC by dividing those still active in care by the total number that started after subtracting those who died and transferred out from both the numerator and denominator.

Younger adolescents (10-14 years) demonstrated better RiC rates, compared with the older group. This observation could be attributed to the disproportionate attention offered to younger adolescents. In spite of the unique challenges posed by adolescents and ART, there is a dearth of comprehensive health services for adolescents, including interventions to improve RiC in sub-Saharan Africa.19 Nevertheless, younger adolescents show better RiC rates because they depend, to a greater extent, on their caregivers to handle their treatment journey. In this way, the RiC of the young adolescent is an extension of the dedication and understanding of the caregiver. Another study designed to investigate the RiC rates between younger and older adolescents in Zimbabwe demonstrated no differences in attrition amongst younger versus older adolescents.20

We found that older adolescents (15-19 years) were significantly less likely to be retained in care over the first 24 months, compared with younger adolescents. This finding is congruent with the trends reported in other studies21,22 and corresponds to the transition of adolescents from paediatric to adult HIV programmes - a known high-risk period for disengagement with care.23,24,25 Several authors have argued that patient-level challenges, such as developmental delays, mental health issues, stigma and social support at home and school, must be adequately addressed for a successful transition to take place.26 A supported transition requires a skilful adult treatment team and the provision of facilitated care aimed at overcoming the disruptions of the patient-paediatric provider relationship. The loss of ancillary support is required to foster independence, the exercise of autonomy and the growth of personal responsibility.27,28

Although male adolescents constituted a smaller proportion of the study sample, on average, they had greater RiC throughout the observation period, compared with females. Just under half of the female adolescents (n = 84/182, 46%) were initiated on ART whilst pregnant. They exited care at an alarming rate, that is, 44%, 64% and 79% at 4, 12 and 24 months, respectively. These findings correspond to those of Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha et al. who found a greater rate of LTFU amongst pregnant and non-pregnant female adolescents, compared with male adolescents.29 The current study reports lower RiC rates, compared with the 76.4% RiC at 12 months noted in a recent systematic review of pregnant and post-partum women in Africa.30 This report found younger age and same-day ART initiation to be risk factors for poor retention, as was initiating during pregnancy, particularly late pregnancy.

Our findings indicate that adolescents who were classified as WHO stage IV at ART initiation showed better RiC rates at months 4, 12 and 24 post-initiation, although no statistical significance was achieved. Individuals at WHO stages III and IV are likely to remain in care because they are motivated by their health status and by the association between treatment and health outcomes. Clinicians tend to monitor individuals who are at WHO stages III and IV more closely because of other comorbidities such as tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections requiring clinical assessments. However, Matyanga et al. found that a low CD4 count and advanced HIV infection at initiation were associated with LTFU.20 We also found that adolescents classified as WHO stage I at ART initiation had significantly lower rates of RiC at 4 months post-initiation versus those with a WHO stage III. Contrary to the results in our study, another Ugandan study found that the risk of LTFU of adolescents at 12 months was significantly greater amongst those on WHO clinical stages III and IV, compared with those on WHO stages I and II.31 People living with HIV at WHO stage I hardly display signs and symptoms associated with AIDS. The literature has attributed this low RiC behaviour amongst adolescents at stage I to not feeling 'sick' or feeling 'well' as a proxy of nothing being wrong.

Although the primary focus of our study was not on pregnant, HIV-infected adolescents, many in this sub-group were captured in our sample. This could be explained by the fact that pregnant, HIV-infected adolescents are often horizontally infected and receive their positive HIV test result for the first time when booking for antenatal care. Although vertical transmission of HIV is common amongst younger ALWH, horizontal transmission is a frequent mode of transmission in older adolescents. Adolescent boys tend to not access HIV treatment because they mostly remain asymptomatic at this stage.

Interventions such as task shifting, community-based adherence support, mHealth platforms and group adherence counselling emerged as strategies in adult populations that could be adapted for adolescents.32,33 These interventions may benefit older adolescents, especially those transitioning to adult programmes that utilise them. However, the effectiveness of, for example, 'teen clubs', has had mixed results. MacKenzie et al.34 reported that Malawian ALWH who were not in a teen club were less likely to be retained than those in teen clubs. On the other hand, Munyayi and van Wyk35 found that group-based adherence interventions such as teen clubs did not improve retention rates for younger adolescents in specialised paediatric ART clinics in Namibia but did hold potential for improving rates in older adolescents. Adolescent-only clinics and monthly meetings have been shown to improve the RiC of adolescents.36 To this end, we support the calls of other authors for interventions, especially targeting older adolescents whose needs are increased during the transition period.23

Conclusion

Our study highlights low RiC for adolescents over the first 2 years after initiation on ART. Critical intervention is needed to motivate adolescents to remain in care, adhere to treatment and ultimately to achieve and maintain VL suppression (even when they are not feeling sick). Targeted interventions to address transition coordination - pre- and post-transition from paediatric to adult HIV programmes - are needed to counter older adolescents dropping out of care. Female adolescents who initiate ART whilst pregnant should receive special attention. This aligns with the increased need to provide and integrate appropriate sexual reproductive health services to ALWH. Behavioural interventions to improve adherence and RiC should ideally be embedded in community health services so that this forms part of an 'extended' HIV treatment package.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

E.K. conducted the research under the supervision of B.v.W., and F.M. and B.v.W. drafted the first manuscript. E.K. and F.M. commented on all drafts. All authors approved the final version.

Funding information

This project was supported under a Medical Research Council of South Africa Self-Initiated Research grant.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request to the author.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the South African Medical Research Council or University of the Western Cape.

References

1.UNICEF. Turning the tide against AIDS will require more concentrated focus on adolescents and young people [homepage on the Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 21]. [ Links ] Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/

2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Data [homepage on the Internet]. [ Links ] 2018 [cited 2019 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf

3.South African National HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey [homepage on the Internet]. [ Links ] 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 03]. Available from: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/9234/SABSSMV_Impact_Assessment_ Summary_ZA_ADS_cleared_PDFA4.pdf

4.Maskew M, Bor J, MacLeod W, Carmona S, Sherman GG, Fox MP. Adolescent HHIV treatment in South Africa's national HIV programme: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(11):e760-e768. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30234-6 [ Links ]

5.UNICEF. Children and AIDS [homepage on the Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 18]. [ Links ] Available from: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/HIVAIDS-Statistical-Update-2017.pdf

6.UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic [homepage on the Internet]. [ Links ] UNAIDS; 2014 [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf

7.Mugglin C, Haas AD, Van Oosterhout JJ, et al. Long-term retention on antiretroviral therapy among infants, children, adolescents and adults in Malawi-term retention on antiretroviral therapy among infants, children, adolescents and adults in Malawi: A cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224837. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224837 [ Links ]

8.Wong VJ, Murray KR, Phelps BR, Vermund SH, McCarraher DR. Adolescents, young people, and the 90-90-90 goals: A call to improve HIV testing and linkage to treatment. AIDS. 2019;31(Suppl. 3):S191-S194. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001539 [ Links ]

9.Nglazi MD, Kranzer K, Holele P, et al. Treatment outcomes in HIV-infected adolescents attending a community-based antiretroviral therapy clinic in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-21 [ Links ]

10.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Nguyen H, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, virologic and immunological outcomes in adolescents compared with adults in southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(1):65-71. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199072e [ Links ]

11.Kariminia A, Law M, Davies M, et al. Mortality and losses to follow-up among adolescents living with HIV in the IeDEA global cohort collaboration. JIAS. 2018;21:e25215. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25215 [ Links ]

12.Western Cape Government Health. 2016. The Western Cape consolidated guidelines for HIV treatment: Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), children, adolescents and adults. Western Cape: Western Cape Government Health. [ Links ]

13.Western Cape Government Health: HAST. June 2017 ART data sign-off document. Western Cape: Western Cape Government Health; 2017. [ Links ]

14.Osler M, Hilderbrand K, Hennessey C, et al. A three-tier framework for monitoring antiretroviral therapy in high HIV burden settings. JIAS. 2014;17:18908. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.18908 [ Links ]

15.Lilian RR, Rees K, McIntyre JA, Struthers HE, Peters RPH. Same-day antiretroviral therapy initiation for HIV-infected adults in South Africa: Analysis of routine data. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227572. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227572 [ Links ]

16.Western Cape Government Health. Update to antiretroviral guidelines: Circular H116 of 2012 [homepage on the Internet]. [ Links ] 2012 [cited 2017 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.doh.gov.za.

17.Nabukeera-Barungi N, Elyanu P, Asire B, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for adolescents living with HIV from 10 districts in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:520. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1265-5 [ Links ]

18.Zanoni BC, Archary M, Buchan S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the adolescent HIV continuum of care in South Africa: The Cresting Wave. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1:e000004. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000004 [ Links ]

19.Adejumo OA, Malee KM, Ryscavage P, Hunter SJ, Taiwo BO. Contemporary issues on the epidemiology and antiretroviral adherence of HIV-infected adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A narrative review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):20049. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.1.20049 [ Links ]

20.Matyanga CMJ, Takarinda KC, Owiti P, et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral therapy among younger versus older adolescents and adults in an urban clinic, Zimbabwe. Public Health Action. 2016;6(2):97-104. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.15.0077 [ Links ]

21.Kranzer K, Bradley J, Musaazi J, et al. Loss to follow-up among children and adolescents growing up with HIV infection: Age really matters. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21737. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.1.21737 [ Links ]

22.Okoboi S, Ssali L, Yansaneh A, et al. Factors associated with long-term antiretroviral therapy attrition among adolescents in rural Uganda: A retrospective study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(554):20841. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.19.5.20841 [ Links ]

23.Dahourou DL, Gautier-Lafaye C, Teasdale CA, et al. Transition from paediatric to adult care of adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, youth-friendly models, and outcomes. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl. 3):21528. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.4.21528 [ Links ]

24.Cervia JS. Easing the transition of HIV infected adolescents to adult care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(12):692-696. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0253 [ Links ]

25.Pinzón-Iregui MC, Ibanez G, Beck-Sagué C, Halpern M, Mendoza RM. '… like because you are grownup, you do not need help': Experiences of transition from pediatric to adult care among youth with perinatal HIV infection, their caregivers, and health care providers in the Dominican Republic. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(6):579-587. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325957417729749 [ Links ]

26.Vijayan T, Benin AL, Wagner K, et al. We never thought this would happen: Transitioning care of adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV infection from paediatrics to internal medicine. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1222-1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120902730054 [ Links ]

27.Jones C, Ritchwood TD, Taggart T. Barriers and facilitators to the successful transition of adolescents living with HIV from pediatric to adult care in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and policy analysis. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(9):2498-2513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02621-6 [ Links ]

28.Kung TH, Wallace ML, Snyder KL, et al. South African healthcare provider perspectives on transitioning adolescents into adult HIV care. SAMJ. 2016;106(8):804-808. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i8.10496 [ Links ]

29.Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Kiragga AN, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Adolescent pregnancy at antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation: A critical barrier to retention on ART. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21:e25178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25178 [ Links ]

30.Knettel BA, Cichowitz C, Ngocho JS, et al. Retention in HIV care during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the option B+ era: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(5):427-438. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.000000000001616 [ Links ]

31.Ssali L, Kalibala S, Birungi J, et al. Retention of adolescents living with HIV in care, treatment, and support programs in Uganda. 2014; Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development. Available from: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2014HIVCore_UgandaAdolHAART.pdf. [ Links ]

32.Ridgeway K, Dulli LS, Murray KR, et al. Interventions to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189770 [ Links ]

33.Murray KR, Dulli LS, Ridgeway K, et al. Improving retention in HIV care among adolescents and adults in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184879. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184879 [ Links ]

34.MacKenzie RK, Van Lettow M, Gondwe C, et al. Greater retention in care amongst adolescents on antiretroviral treatment accessing 'Teen Club' an adolescent-centred differentiated care model compared with standard of care: A nested case-control study at a tertiary referral hospital in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(3):e25028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25028 [ Links ]

35.Munyayi F, Van Wyk B. The effects of teen clubs on retention in HIV care amongst adolescents in Windhoek, Namibia. S Afr J HIV Med. 2020;21(1):a1031. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v21i1.1031 [ Links ]

36.Izudi J, Mugenyi J, Mugabekazi M, Spector VT, Katawera A, Kekitiinwa A. Retention of HIV-positive adolescents in care: A quality improvement intervention in mid-western Uganda. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:1524016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1524016 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Brian van Wyk

bvanwyk@uwc.ac.za

Received: 12 Feb. 2020

Accepted: 23 May 2020

Published: 22 July 2020

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The spectrum of electrolyte abnormalities in black African people living with human immunodeficiency virus and diabetes mellitus at Edendale Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

Preyanka PillayI, II; Somasundram PillayIII, IV; Nobuhle MchunuV, VI

IDepartment of Internal Medicine, Greys Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

IISchool of Clinical Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Internal Medicine, Edendale Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

IVDepartment of Internal Medicine, King Edward Hospital, Durban, South Africa

VDepartment of Biostatistics, Faculty of Statistics, South African Medical Research Council, Durban, South Africa

VIDepartment of Statistics, School of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Serum electrolyte abnormalities in black African people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and diabetes mellitus (PLWH/DM) is unknown.

OBJECTIVES: The aim of this study was to analyse serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium and phosphate) and factors associated with electrolyte abnormalities in black African PLWH/DM versus HIV-uninfected patients with DM.

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective case-control study in 96 black African PLWH/DM (cases) and 192 HIV-uninfected patients with DM (controls), who were visiting the Edendale Hospital DM clinic, from 01 January 2016 to 31 December 2016. Pearson's correlation, multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses were utilised.

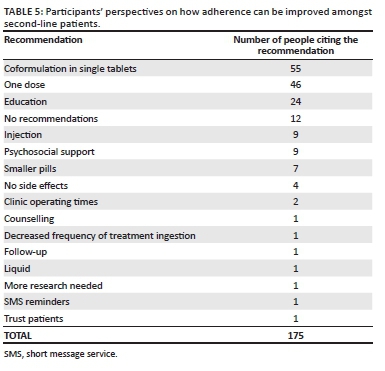

RESULTS: Hypocalcaemia was the most frequent electrolyte abnormality in PLWH/DM and HIV-uninfected patients with DM (31.25% vs. 22.91%), followed by hyponatraemia (18.75% vs. 13.54%). Median (IQR) corrected serum calcium levels were significantly lower in PLWH/DM compared with HIV-uninfected patients with DM (2.24 [2.18-2.30] mmol/L vs. 2.29 [2.20-2.36] mmol/L; p = 0.001). For every per cent increase in glycated haemoglobin, the odds of hyponatraemia significantly increased in both PLWH/DM (odds ratio [OR]: 1.55; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.19 -2.02; p = 0.003) and HIV-uninfected patients with DM (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.04 -1.54; p = 0.009.

CONCLUSION: Hypocalcaemia and hyponatraemia were the most frequent electrolyte abnormalities and occurred more frequently in PLWH/DM compared with HIV-uninfected patients with DM. People living with HIV and DM have significantly lower corrected serum calcium levels compared with HIV-uninfected patients with DM. Furthermore, hyponatraemia is a marker of impaired glycaemic control.

Keywords: HIV; diabetes mellitus; electrolytes; sodium; potassium; calcium; phosphate; black African.

Introduction