Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine

versión On-line ISSN 2078-6751

versión impresa ISSN 1608-9693

South. Afr. j. HIV med. (Online) vol.21 no.1 Johannesburg 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v21i1.1039

11.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, Leibowitz AA. Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1136-1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.554528 [ Links ]

12.Peng B, Yang X, Zhang Y, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among female sex workers: A cross-sectional study in China. HIV AIDS. 2012;4:149-158. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S33445 [ Links ]

13.Reza-Paul S, Lazarus L, Doshi M, et al. Prioritizing risk in preparation for a demonstration project: A mixed methods feasibility study of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PREP) among female sex workers in South India. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166889 [ Links ]

14.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV-infection: Baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):439-448. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479 [ Links ]

15.Whetham J, Taylor S, Charlwood L, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for conception (PrEP-C) as a risk reduction strategy in HIV-positive men and HIV-negative women in the UK. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):332-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.819406 [ Links ]

16.Vernazza PL, Graf I, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, Geit M, Meurer A. Preexposure prophylaxis and timed intercourse for HIV-discordant couples willing to conceive a child. AIDS. 2011;25(16):2005-2008. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a36d0 [ Links ]

17.Dolling DI, Desai M, McOwan A, et al. An analysis of baseline data from the PROUD study: An open-label randomised trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis. Trials. 2016;17:163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1286-4 [ Links ]

18.Elmes J, Nhongo K, Ward H, et al. The price of sex: Condom use and the determinants of the price of sex among female sex workers in eastern Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 2014;210 (Suppl 2):S569-S578. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu493 [ Links ]

19.Wilton J, Senn H, Sharma M, Tan DH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for sexually-acquired HIV risk management: A review. HIV AIDS. 2015;7:125-136. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S50025 [ Links ]

20.Mack N, Odhiambo J, Wong CM, Agot K. Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) eligibility screening and ongoing HIV testing among target populations in Bondo and Rarieda, Kenya: Results of a consultation with community stakeholders. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:231. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-231 [ Links ]

21.Heffron R, Celum C, Mugo N, et al., editors. High initiation of PrEP and ART in a demonstration project among African HIV-discordant couples. 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2014 March 03-06; Boston, MA: International Aids Society; 2014. [ Links ]

22.Restar AJ, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre- and post-exposure prophylaxes (PrEP and PEP) among female and male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya: Implications for integrating biomedical prevention into sexual health services. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(2):141-153. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2017.29.2.141 [ Links ]

23.Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(2):102-110. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Tinashe Mudzviti

tinashem@newlandsclinic.org.zw

Received: 22 Oct. 2019

Accepted: 11 Jan. 2020

Published: 19 Feb. 2020

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Implementation of a PMTCT programme in a high HIV prevalence setting in Johannesburg, South Africa: 2002-2015

Coceka N. MnyaniI, II; Carol L. TaitIII; Remco P.H. PetersIII, IV; Helen StruthersIII, V; Avy ViolariVI; Glenda GrayVI; Eckhart J. BuchmannI; Matthew F. ChersichVII; James A. McIntyreIII, VIII

IDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IISouth African Centre of Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis (SACEMA), DST-NRF Centre for Excellence, Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

IIIAnova Health Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVDepartment of Medical Microbiology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

VDivision of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

VIPerinatal HIV Research Unit, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIWits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIISchool of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Great strides have been made in decreasing paediatric human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In South Africa, new paediatric HIV infections decreased by 84% between 2009 and 2015. This achievement is a result of a strong political will and the rapid evolution of the country's prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) guidelines.

OBJECTIVES: In this paper we report on the implementation of a large PMTCT programme in Soweto, South Africa.

METHODS: We reviewed routinely collected PMTCT data from 13 healthcare facilities, for the period 2002-2015. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage among pregnant women living with HIV (PWLHIV) and the mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) rate at early infant diagnosis were evaluated.

RESULTS: In total, 360 751 pregnant women attended the facilities during the review period, and the HIV prevalence remained high throughout at around 30%. The proportion of PWLHIV presenting with a known HIV status increased from 14.3% in 2009 when the indicator was first collected to 45% in 2015, p < 0.001. In 2006, less than 10% of the PWLHIV were initiated on ART, increasing to 88% by 2011. The MTCT rate decreased from 6.9% in 2007 to under 1% from 2013 to 2015, p < 0.001.

CONCLUSION: The achievements in decreasing paediatric HIV infections have been hailed as one of the greatest public health achievements of our times. While there are inherent limitations with using routinely collected aggregate data, the Soweto data reflect progress made in the implementation of PMTCT programmes in South Africa. Progress with PMTCT has, however, not been accompanied by a decline in HIV prevalence among pregnant women.

Keywords: PMTCT; South Africa; pregnant women living with HIV (PWLHIV); paediatric HIV infection; health systems.

Background

Great strides have been made in the global fight to decrease new paediatric human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections. In 2011, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) launched the Global Plan to reduce new paediatric HIV infections by 90%, by 2015, with the baseline year being 2009.1 The target was to decrease the rate of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV to 2% or less among non-breastfeeding women, and to 5% or less among breastfeeding women.1 As part of the Global Plan, 22 priority countries, which together accounted for 90% of the global number of pregnant women living with HIV (PWLHIV) in 2009, were identified for intensified efforts for the elimination of MTCT.1 India and 21 countries in sub-Saharan Africa made up the 22 priority countries.1

According to the 2016 UNAIDS report, there was a 60% decrease in the overall MTCT rate in 21 priority countries, from 22.4% in 2009 to 8.9% in 2015 (data on India were not available).2 The decrease in the MTCT rate is largely because of the increased coverage of more efficacious antiretroviral regimens for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV.2,3,4,5 South Africa was identified as one of the 22 priority countries, and through strong political will and rapid evolution of the country's PMTCT guidelines, new paediatric HIV infections decreased by 84% between 2009 and 2015, with an estimated 330 000 infections averted.2 The UNAIDS estimate for the MTCT rate for South Africa in 2015 was 2%. This was consistent with findings from a national survey conducted in 2012-2013, involving over 9000 infant-caregiver pairs, with an MTCT rate of 2.6% at 4-8 weeks.2,6

Donor funding has been critical in the establishment of the South African PMTCT and antiretroviral therapy (ART) programmes, with the country being the largest recipient of grants from the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).7,8,9,10,11 President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief funding of HIV programmes in South Africa started in 2004, with direct service provision through the placement of staff and infrastructure in public healthcare facilities.8,10 From 2012, there was a transition in PEPFAR funding from direct service provision to technical support, with the South African government increasingly taking up ownership of the country's HIV programme.8,11 By 2016, more than 75% of South Africa's HIV response was funded by the government.12

This article reports on the outcomes of a large PMTCT programme in Soweto, South Africa, over time, including the coverage of ART among PWLHIV and the MTCT rate at approximately 6 weeks of age.

Methods

Study setting and design

We conducted a retrospective study of routinely collected PMTCT data from 13 public healthcare facilities that have been part of the Soweto PMTCT programme since its inception in 2002. Of the 13 facilities, one is a tertiary-level referral hospital (Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital), and 12 are primary healthcare facilities, of which six have delivery units. Soweto is an area of mixed urban and informal settlements, with an estimated population of approximately 1.7 million people.13

History of the Soweto prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme

The Soweto PMTCT programme was established in 2000 as the Demonstration of Antiretroviral Treatment (DART) programme initiated by the Perinatal HIV Research Unit (PHRU).14 The programme was initially funded by the Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF) with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Fonds De Solidarité Thérapeutique International (FSTI) and the Gauteng Department of Health, and from 2004 it was funded by PEPFAR, through the USAID.14 As part of the DART programme, pregnant women were offered voluntary counselling and testing for HIV and, if found to be HIV-positive, were issued a single-dose nevirapine (NVP) to be taken intrapartum, and also a single-dose NVP to be given to the infant immediately after birth. A free 6-month supply of infant formula was also available for women living with HIV who elected not to breastfeed.

The programme evolved in line with changes in the South African PMTCT and ART guidelines, and since 2009, the programme has been supported by the Anova Health Institute (Anova), a USAID/PEPFAR-funded non-profit organisation. The donor-funded support was initially through direct service provision with placement of staff - doctors, professional nurses, data collectors and lay counsellors - in public health facilities working alongside government employees. There was also infrastructure, pharmacy, and monitoring and evaluation support for the facilities providing HIV services. With the PEPFAR funding transitioning to technical support, the focus in support shifted to mentoring and quality improvement of the programmes through monitoring and evaluation.

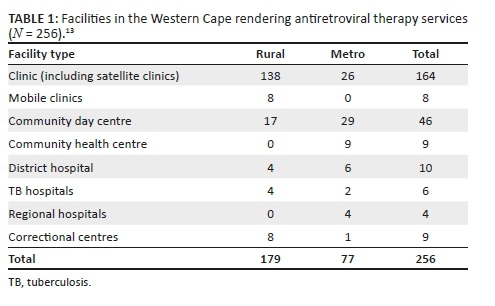

Evolution of the South African prevention of mother-to-child transmission guidelines

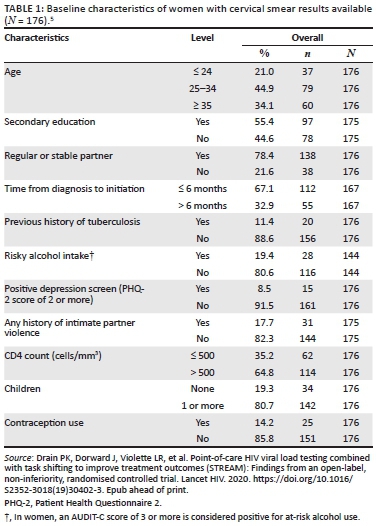

Prior to 2002, no antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis or treatment was available in the South African public health sector, and ARVs were only available as part of research projects.15,16,17 From 2002 until 2007, only mother-infant single-dose NVP was available for PMTCT (Table 1). Additional zidovudine (AZT) monotherapy for PMTCT prophylaxis was introduced in 2008, initially started at 28 weeks' gestation, and from 2010 at 14 weeks' gestation.18,19,20 Antiretroviral therapy became available in South Africa in 2004 and the eligibility criterion was a CD4 count of < 200 cells/µL, or World Health Organization (WHO) stage 4 disease.21 CD4 count testing to assess ART eligibility became routinely available from 2005. The CD4 count threshold for ART initiation in pregnant women increased to ≤ 350 cells/µL in 2010.20

Up to September 2010, the antenatal clinics in the 12 primary healthcare facilities only provided antiretroviral prophylaxis for PMTCT, and PWLHIV who were eligible for lifelong ART were referred to a separate ART initiation site. In that time period, the only antenatal clinic that initiated ART was at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital. At the primary health clinics, pregnant women diagnosed with HIV infection were referred to an ART initiation site, which could be in a different section of the same health facility, or in a different facility. Over a period of 18 months, beginning in October 2010, nurse-initiated and managed ART (NIMART) was introduced in the antenatal clinics, with PWLHIV receiving their antenatal and HIV care in the same facility. Nurse-initiated and managed ART, a task-shifting initiative to increase the number of patients initiated on ART, meant that professional nurses, including midwives, could initiate and manage patients on ART.22 Postpartum, the women were transitioned to adult HIV care for follow-up. From 2002 until 2011, a 6-month supply of free infant formula was available for all WLHIV who elected not to breastfeed.

In 2013, WHO Option B, where all pregnant and postpartum WLHIV were initiated on an efavirenz-based fixed-dose combination, was introduced.23 Treatment was stopped postpartum if not breastfeeding, or after cessation of breastfeeding, if the woman was not eligible for lifelong ART for her own health.23 The most recent PMTCT guideline change was in 2015 when all pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV became eligible for lifelong treatment regardless of CD4 count level, Option B+.24

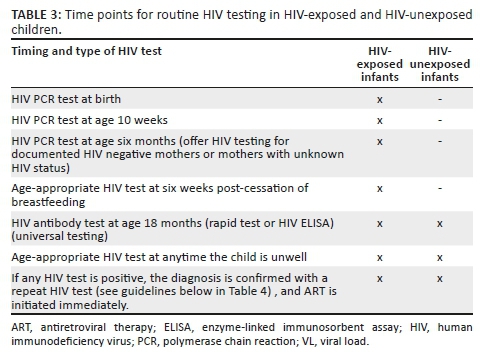

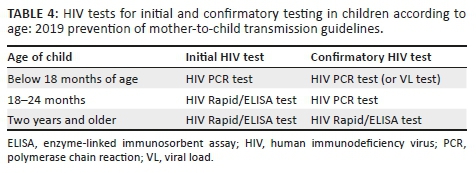

The 2013 PMTCT guideline reinforced the recommendation that was first made in the 2010 guideline that pregnant women who initially tested HIV-negative were to be routinely retested during pregnancy at around 32 weeks' gestation. For women who presented intrapartum with an unknown HIV status, or with a negative HIV test done prior to 32 weeks' gestation, or done more than 12 weeks prior to delivery, the recommendation was for retesting intrapartum. Postpartum, the recommendation was to repeat the HIV test at 6 weeks postpartum and every 3 months during breastfeeding. In the 2015 guidelines, the recommendation is for routine repeat HIV testing every 3 months during pregnancy, intrapartum and postpartum as per the 2013 guidelines. Routine testing of HIV-exposed infants, using HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR), became standard of care from 2004, and was offered at around 6 weeks of age. Also, as part of routine care, an HIV antibody test was done at 18 months in infants who initially tested negative at early infant diagnosis. Since 2015, routine testing of HIV-exposed infants was done at birth, 10 weeks of infant age, 6 weeks post-cessation of breastfeeding and at 18 months.

It is in this background of evolving guidelines and the changing focus of donor funding that we evaluated the Soweto PMTCT programme.

Data management and analysis

As part of routine reporting to the District Health and Information System (DHIS), PMTCT data were collected on PWLHIV and HIV-exposed infants, and the indicators collected changed over time with evolving PMTCT guidelines. We extracted aggregate data from paper-based and electronic registers on core PMTCT indicators for the period 2002-2015. The indicators that we collected data for include the following: pregnant women presenting for their first antenatal visit and gestational age at first visit; pregnant women tested for HIV during pregnancy and those presenting already known to be living with HIV and whether already on ART; PWLHIV who were issued with single-dose NVP prophylaxis antenatally; PWLHIV who had a CD4 count done during pregnancy and those who had a CD4 count of < 200 cells/µL and ≤ 350 cells/µL; the number of ART-eligible pregnant women who were initiated on ART; and the number of HIV-exposed infants who were tested for HIV and those found to be HIV-positive.

The prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus among pregnant women was calculated using the number of pregnant women presenting at the first antenatal visit already known to be living with HIV and those newly diagnosed as HIV-positive during pregnancy as the numerator and the total number of first visits as the denominator. The proportion of ART-eligible pregnant women was calculated using the number of PWLHIV who had a CD4 count of < 200 cells/µL or ≤ 350 cells/µL, depending on the CD4 count threshold at the time, divided by the total number who had a CD4 count done. For the 2013-2015 data, all PWLHIV who were not on ART at the first antenatal visit were regarded as eligible for treatment, in line with the guidelines. The number of HIV-exposed infants who were found to be HIV-positive at around 6 weeks of age was used to calculate the MTCT rate, using as the denominator the number of HIV-exposed infants tested in the 13 facilities. Data were analysed using Stata® version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference No. M140461), and access to the facilities was granted by the Johannesburg Health District Office.

Results

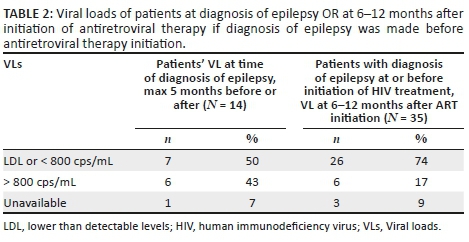

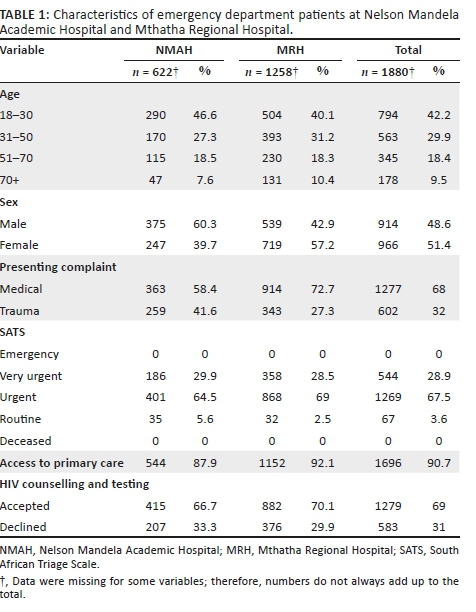

From January 2002 to December 2008, around 30 000 pregnant women presenting for their first antenatal visit were seen in the programme annually (Table 2). As services became decentralised, and more facilities started providing antenatal services, and PMTCT and ART care, the number of pregnant women seen in the 13 facilities decreased from 2009 onwards. Most pregnant women presented for antenatal care after 20 weeks' gestation; the proportion doing so increased from 40.8% in 2010 when the indicator was first collected, to 51.3% in 2015, p < 0.001. There was also a progressive increase in pregnant women known to be living with HIV, presenting from 14.3% in 2009 to 45.0% 2015, p < 0.001. Human immunodeficiency virus testing rates during pregnancy were high throughout the study period, increasing from 95.8% in 2002 to 100% by 2010. The HIV prevalence was high from the beginning of the review period in 2002, with 28.9% of pregnant women found to be living with HIV, reaching a peak of 33.1% in 2009 (Table 2). From 2002 to 2007, when only single-dose NVP was available for PMTCT prophylaxis and issued at the first antenatal visit, the proportion of women who were issued prophylaxis peaked at 96.1% within 1 year of the implementation of the programme. Over time, the proportion of women who were issued NVP prophylaxis at the first antenatal visit decreased, as there was a shift to issuing the prophylaxis intrapartum.

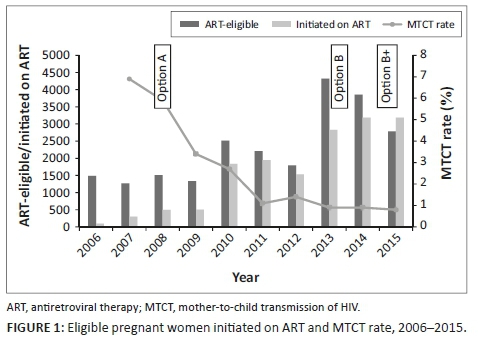

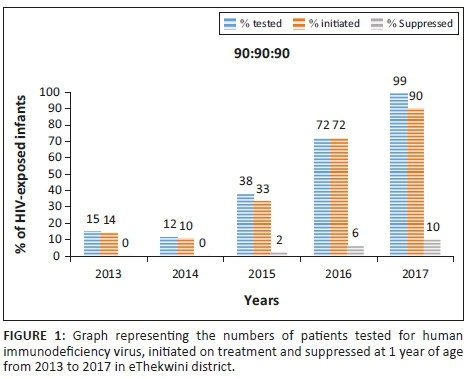

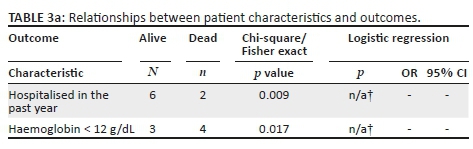

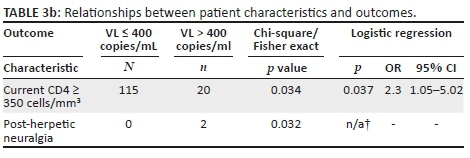

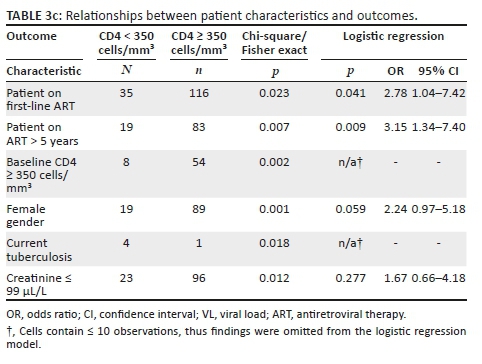

With the CD4 count threshold for ART eligibility at < 200 cells/µL from 2005 to 2009, approximately 16% of PWLHIV were eligible for ART. When the CD4 count threshold was increased to ≤ 350 cells/µL in 2010, the proportion of ART-eligible pregnant women increased to around 40%. There was a progressive increase in the proportion of eligible women initiated on ART, from less than 10% in 2006 to over 80% by 2011 (Table 3 and Figure 1). From 2013, all PWLHIV were eligible to be started on ART regardless of the CD4 count level. Data for routine PCR testing of HIV-exposed infants, at around 6 weeks of age, are available for the period 2007-2015. A total of 41 948 PCR tests, with results, were reported, and of these, 1195 were found to be positive (Table 4). The MTCT rate at around 6 weeks of age decreased from 7.0% in 2007 to less than 1% in 2013-2015, p < 0.001 (Figure 1).

Discussion

In this 14-year review of the Soweto PMTCT programme, there was a progressive decline in the MTCT rate, at approximately 6 weeks of age, to under 1% by 2013. The decrease coincides with an increase in the proportion of PWLHIV initiated on ART, as the PMTCT guidelines evolved. Coverage of HIV testing of pregnant women was high throughout the study. The HIV prevalence remained high, with no discernible change over time. Donor funding and local non-governmental organisation (NGO) support were critical in the establishment of the Soweto PMTCT programme, and the collaboration with the South African Department of Health ensured sustainability of the programme.

While NVP and AZT monotherapy prophylaxis were important in decreasing the risk of MTCT in low-resource settings with limited access to ART, the greatest risk of transmission is in women with high viral loads who receive no or limited duration of ART during pregnancy.25 The decrease in the perinatal transmission rate in the Soweto programme became evident from 2008 to 2013, a period of rapid evolution of the South African PMTCT guidelines. The period saw the introduction of dual prophylaxis for PMTCT, an increase in the CD4 threshold for ART eligibility in pregnant women and also the introduction of NIMART within antenatal clinics.19,20,23 The decline in MTCT rate to below 2% coincided with the rapid increase in the number of ART-eligible pregnant women initiated on treatment in the programme. Integration of antenatal and HIV services, which was introduced in the programme in 2010, has been shown to increase the proportion of ART-eligible pregnant women initiated on ART.26,27 The infant HIV PCR testing reported does not reflect coverage, as testing was done in several other facilities in the Soweto area, not reported in this article. In spite of this, the trend in the decline in the MTCT rate is similar to that shown in published data in South Africa. It is also similar to the National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) data for the Greater Soweto area which show a decline in the MTCT rate from 8.2% in 2007, to 1.6% in 2015 (personal communication, G. Sherman). While we did not have figures on breastfeeding transmission, postpartum MTCT remains a challenge with the 2016 UNAIDS report estimating that more than 50% of new HIV infections among children occur during the breastfeeding period.2

In spite of the gains made towards the elimination of MTCT in South Africa, several challenges remain.28 Only limited progress has been made in the prevention of new HIV infections among women of reproductive age, an important aspect of PMTCT.2 South Africa is reported to have had the highest number of new HIV infections among women of reproductive age globally in the period 2009-2015, and this is reflected in the high HIV prevalence among pregnant women, a consistent finding throughout the review period in our study.2,29 The finding of a consistently high HIV prevalence is similar to figures reported in the national antenatal sentinel HIV prevalence surveys that have been conducted in South Africa since 1990.29 Pregnant women in South Africa as a whole still present at an advanced gestational age for their first antenatal visit, with just over 50% reported to have presented before 20 weeks in 2014, albeit this being an increase from 36.7% in 2010.5 We found similar figures in our study.

The delayed presentation for antenatal care results in late ART initiation in those diagnosed as living with HIV during pregnancy. In our study, the majority of women were first diagnosed as living with HIV during their pregnancies, a finding reported in several studies conducted in South Africa and other sub-Saharan African countries, although this figure decreased over time.30,31,32,33 In spite of the late presentation for antenatal care, there was a steady increase in the proportion initiated on ART during pregnancy, a trend reported in published DHIS data.34 Among pregnant women who presented already known to be living with HIV, the proportion already on ART was high, a finding similar to that reported in the 2017 South African national antenatal sentinel HIV prevalence survey.29

One of the limitations of using aggregate data is that the denominators used to calculate rates for some of the indicators are proxy indicators. The data presented are the best available representation of the ideal, which would have been to have longitudinal data on each patient, from HIV diagnosis to the initiation of ART, and also have delivery details and linked infant HIV testing. The indicators collected also changed over time as guidelines changed. Details on the denominators used are presented in the 'Results' section. For HIV testing rates, no data were collected prior to 2009 on PWLHIV who already knew their HIV status and those who were already on ART. Hence, in this period, among those newly identified as HIV-positive, there will have been a proportion of PWLHIV who already knew their HIV status and may have been on treatment. Prior to 2013, for the indicators on PWLHIV assessed for ART eligibility and initiated on treatment, the numerator and denominator do not reflect the same group of women seen in 1 month, but the numbers even out over several months. Criteria for ART eligibility are reported in the 'Results' section. There were no data available on ART eligibility based on the WHO clinical staging.

There are also additional limitations with using routine, aggregate data, and these are related to the completeness and accuracy of the data.35,36 In their assessment of routinely collected PMTCT data from 57 public health facilities in South Africa, Nicol et al. raised concerns about the quality and consistency of reported data.36 The main discrepancies identified were between data in paper-based registers and the monthly facility reports.36 The discrepancies highlighted problems with data capturing related to lack of sufficient staff, and competence in recording and validation of data.36 In the Soweto PMTCT programme, there have always been dedicated data collectors and data managers involved in monitoring and evaluation of the programme. While recording of data in the facility registers remains primarily the responsibility of staff working at the healthcare facilities, data managers are involved in the validation of data and overseeing their work.

In spite of the limitations of the study, the Soweto PMTCT programme is a success story of the collaboration between donor-funded organisations and the South African Department of Health. The strength of this study is that it reports on a large PMTCT programme, over a long review period. While there are inherent inaccuracies with routinely collected aggregate data, the trends reported in this article are similar to those reported in published DHIS data and national surveys in South Africa.29,34,37 To our knowledge, no PMTCT data of this magnitude have been published from a low-resource, high HIV prevalence setting. Data from the programme illustrate that it is possible to significantly decrease the MTCT rate even in a high HIV prevalence setting. It is important to ensure that the gains made towards elimination of MTCT are sustained beyond the immediate postpartum period, and also ensure that HIV-exposed uninfected infants survive and thrive.38 There also needs to be a concerted effort to decrease the rate of new HIV infections, especially among women of reproductive age.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the staff who were involved in the implementation of the Soweto PMTCT programme, and also all the mothers and infants who were part of the programme. They would also like to thank Prof. Gayle Sherman for sharing the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) data on infant HIV PCR testing in the Great Soweto area.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

C.N.M. initiated the study and was the main investigator responsible for data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript. R.P.H.P. and C.L.T. were responsible for data collection and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. H.S., A.V. and G.G. contributed to the initiation of the study, data collection and drafting of the manuscript. E.J.B. and M.F.C. contributed to data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. J.A.M. contributed to the initiation of the study, data collection and drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding information

The Soweto PMTCT programme was initially funded by the Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF) with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Fonds De Solidarité Thérapeutique International (FSTI) and the Gauteng Department of Health, and from 2004 onwards it was funded by President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), via the USAID.

This study was funded by the US PEPFAR through the USAID under Cooperative Agreement number 674-A-12-00015 to the Anova Health Institute, Carnegie Corporation of New York PhD Fellowship (Grant number: B 8749.RO1) and SACEMA (DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis), Stellenbosch University.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Countdown to zero: Global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive, 2011-2015. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. [ Links ]

2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). On the fast-track to an AIDS-free generation. The incredible journey of the global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016. [ Links ]

3.Burton R, Giddy J, Stinson K. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission in South Africa: An ever-changing landscape. Obstet Med. 2015;8(1):5-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495X15570994 [ Links ]

4.Bhardwaj S, Barron P, Pillay Y, et al. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: Rapid scale-up using quality improvement. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(3):239-243. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.7605 [ Links ]

5.Millennium Development Goals 5: Improve maternal health [homepage on the Internet]. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2015 [cited 2017 Jun]. Available from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/MDG/MDG_Goal5_report_2015_.pdf [ Links ]

6.Goga AE, Dinh TH, Jackson DJ, et al. South Africa PMTCT Evaluation (SAPMCTE) Team. Population-level effectiveness of PMTCT option A on early mother-to-child (MTCT) transmission of HIV in South Africa: Implications for eliminating MTCT. J Glob Health. 2016;6(2):020405. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.020405 [ Links ]

7.Johnson, K. The politics of AIDS policy development and implementation in post-apartheid South Africa. AfricaToday. 2004;51(2):107-128. https://doi.org/10.1353/at.2005.0007 [ Links ]

8.Katz IT, Bassett IV, Wright AA. PEPFAR in transition - Implications for HIV Care in South Africa. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1385-1387. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1310982 [ Links ]

9.Simelela NP, Venter WD. A brief history of South Africa's response to AIDS. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(3):249-251. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.7700 [ Links ]

10.Kavanagh MM. The politics and epidemiology of transition: PEPFAR and AIDS in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(3):247-250. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000093 [ Links ]

11.Strauss M, Surgey G, Cohen S, for the South African National AIDS Council. A review of the South African Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Grant [homepage on the Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jun]. Available from: http://sanac.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/A-review-of-the-South-African-Conditional-Grant-for-HIV-30Mar-vMS.pdf [ Links ]

12.PEPFAR investing more than $410 Million towards an AIDS-Free generation in South Africa [homepage on the Internet]. Media Advisory. 2016 [cited 2017 Jun]. Available from: https://za.usembassy.gov/pepfar-investing-410-million-towards-aids-free-generation-south-africa/ [ Links ]

13.Population of cities in South Africa [homepage on the Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/south-africa-population/cities/ [ Links ]

14.At the cutting edge of HIV/AIDS research: A review of the Perinatal HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, 1996-2005 [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: https://www.phru.co.za/images/documents/phru_overview.pdf [ Links ]

15.Gray GE, Urban M, Chersich MF, et al. A randomized trial of two postexposure prophylaxis regimens to reduce mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission in infants of untreated mothers. AIDS. 2005;19(12):1289-1297. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000180100.42770.a7 [ Links ]

16.Moodley D, Moodley J, Coovadia H, et al. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of nevirapine versus a combination of zidovudine and lamivudine to reduce intrapartum and early postpartum mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(5):725-735. https://doi.org/10.1086/367898 [ Links ]

17.Petra Study Team. Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1178-1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08214-4 [ Links ]

18.Doherty T, Besser M, Donohue S, et al. An evaluation of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV initiative in South Africa - Lessons and key recommendations [homepage on the Internet]. Durban: Health Systems Trust: 2003 [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://www.hst.org.za/sites/default/files/pmtct_national.pdf [ Links ]

19.National Department of Health. Policy and guidelines for the implementation of the PMTCT Programme. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health; 2008. [ Links ]

20.National Department of Health, South Africa; South African National AIDS Council. Clinical guidelines: PMTCT (prevention of mother-to-child transmission), 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health; 2010 [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/NDOH_PMTCT.pdf [ Links ]

21.National antiretroviral treatment guidelines [homepage on the Internet]. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2004 [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/facts/2004/intro.pdf [ Links ]

22.Colvin CJ, Fairall L, Lewin S, et al. Expanding access to ART in South Africa: The role of nurse-initiated treatment. S Afr Med J. 2010;100(4):210-212. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.4124 [ Links ]

23.Revised antiretroviral treatment guideline update for frontline clinical health professionals [homepage on the Internet]. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health; 2013 [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/FDC%20Training%20Manual%2014%20March%202013 (1).pdf [ Links ]

24.National Consolidated Guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults [homepage on the Internet]. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health; 2015 [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/HIV%20guidelines%20_Jan%202015.pdf [ Links ]

25.Townsend CL, Byrne L, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Earlier initiation of ART and further decline in mother-to-child HIV transmission rates, 2000-2011. AIDS. 2014;28:1049-1057. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000212 [ Links ]

26.Killam WP, Bushimbwa TC, Namwinga C, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in antenatal care to increase treatment initiation in HIV-infected pregnant women: A stepped-wedge evaluation. AIDS. 2010;24(1):85-91. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833298be [ Links ]

27.Stinson K, Jennings K, Myer L. Integration of antiretroviral therapy services into antenatal care increases treatment initiation during pregnancy: A cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63328. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063328 [ Links ]

28.Luzuriaga K, Mofenson LM. Challenges in the elimination of paediatric HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:761-770. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1505256 [ Links ]

29.Woldesenbet SA, Kufa T, Lombard C, et al. The 2017 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV Survey, South Africa. National Department of Health [homepage on the Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jul]. Available from: http://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Antenatal_survey-report_24July19.pdf [ Links ]

30.Wettstein C, Mugglin C, Egger M, et al. Missed opportunities to prevent mother-to-child-transmission: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2012;26(18):2361-2373. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359ab0c [ Links ]

31.Technau KG, Kalk E, Coovadia A, et al. Timing of maternal HIV testing and uptake of prevention of mother-to-child transmission interventions among women and their infected infants in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(5):e170-e178. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000068 [ Links ]

32.Kim MH, Ahmed S, Hosseinipour MC, et al. The impact of Option B+ on the antenatal PMTCT cascade in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:e77-e83. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000517 [ Links ]

33.Herce ME, Mtande T, Chimbwandira F, et al. Supporting option B+ scale up and strengthening the prevention of mother-to-child transmission cascade in central Malawi: Results from a serial cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1065-y [ Links ]

34.Massyn N, Peer N, English R, Padarath A, Barron P, Day C, editors. District health barometer 2015/16. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2016. [ Links ]

35.Barron P, Pillay Y, Doherty T, et al. Eliminating mother-to-child HIV transmission in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(1):70-74. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.106807 [ Links ]

36.Nicol E, Dudley L, Bradshaw D. Assessing the quality of routine data for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: An analytical observational study in two health districts with high HIV prevalence in South Africa. Int J Med Inform. 2016;95:60-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.09.006 [ Links ]

37.Sherman GG, Mazanderani AH, Barron P, et al. Toward elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: How best to monitor early infant infections within the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission Program. J Glob Health. 2017;7(1):010701. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.010701 [ Links ]

38.Evans C, Jones CE, Prendergast AJ. HIV-exposed, uninfected infants: New global challenges in the era of paediatric HIV elimination. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(6):e92-e107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00055-4 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Coceka Mnyani

nandipha.mnyani@gmail.com

Received: 22 Aug. 2019

Accepted: 20 Oct. 2019

Published: 23 Mar. 2020

SCIENTIFIC LETTER

Drug resistance after cessation of efavirenz-based antiretroviral treatment started in pregnancy

Globahan AjibolaI; Christopher RowleyI, II, III; Dorcas MaruapulaI; Jean LeidnerIV; Kara BennettV; Kathleen PowisI, II, VI, VII; Roger L. ShapiroI, II, III; Shahin LockmanI, II, VIII

IBotswana Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health AIDS Initiative Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana

IIDepartment of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, United States

IIIBeth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, United States

IVGoodtables Data Consulting, LLC., Norman, United States

VBennett Statistical Consulting, Inc., Ballston Lake, United States

VIDepartment of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, United States

VIIDepartment of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, United States

VIIIDivision of Infectious Disease, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, United States

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: To reduce risk of antiretroviral resistance when stopping efavirenz (EFV)-based antiretroviral treatment (ART), staggered discontinuation of antiretrovirals (an NRTI tail) is recommended. However, no data directly support this recommendation

OBJECTIVES: We evaluated the prevalence of HIV drug resistance mutations in pregnant women living with HIV who stopped efavirenz (EFV)/emtricitabine (FTC)/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) postpartum

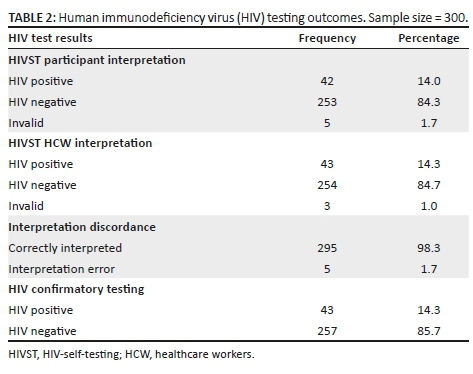

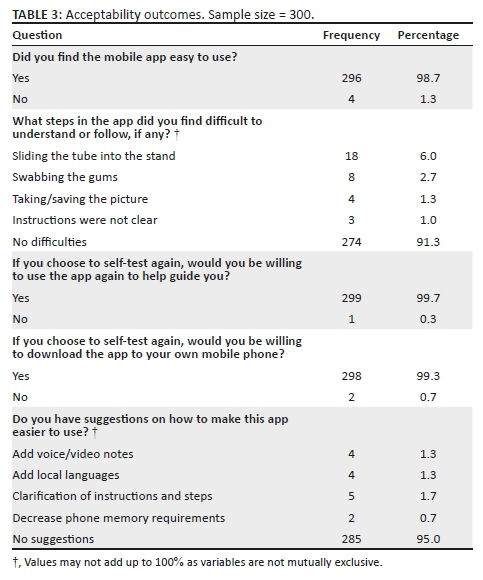

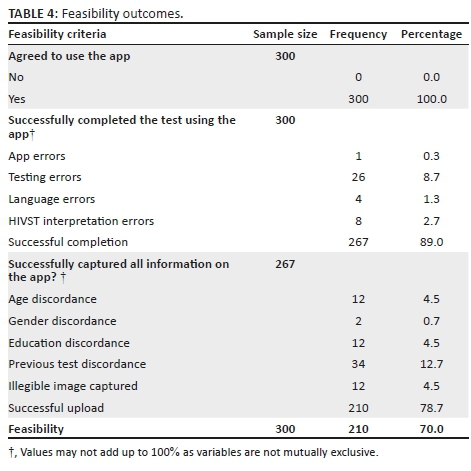

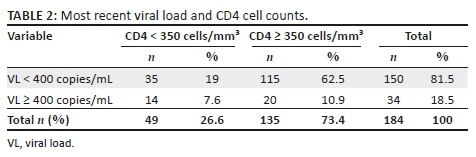

METHOD: In accordance with the prevailing Botswana HIV guidelines at the time, women with pre-treatment CD4 > 350 cells/mm3, initiated EFV/FTC/TDF in pregnancy and stopped ART at 6 weeks postpartum if formula feeding, or 6 weeks after weaning. A 7-day tail of FTC/TDF was recommended per Botswana guidelines. HIV-1 RNA and genotypic resistance testing (bulk sequencing) were performed on samples obtained 4-6 weeks after stopping EFV. Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database was used to identify major mutations

RESULTS: From April 2014 to May 2015, 74 women who had stopped EFV/FTC/TDF enrolled, with median nadir CD4 of 571 cells/mm3. The median time from cessation of EFV to sample draw for genotyping was 5 weeks (range: 3-13 weeks). Thirty-two (43%) women received a 1-week tail of FTC/TDF after stopping EFV. HIV-1 RNA was available from delivery in 70 (95%) women, 58 (83%) of whom had undetectable delivery HIV-1 RNA (< 40 copies/mL). HIV-1 RNA was available for 71 women at the time of genotyping, 45 (63%) of whom had HIV-1 RNA < 40 copies/mL. Thirty-five (47%) of 74 samples yielded a genotype result, and four (11%) had a major drug resistance mutation: two with K103N and two with V106M. All four resistance mutations occurred among women who did not receive an FTC/TDF tail (4/42, 10%), whereas no mutations occurred among 18 genotyped women who had received a 1-week FTC/TDF tail (p = 0.053

CONCLUSIONS: Viral rebound was slow following cessation of EFV/FTC/TDF in the postpartum period. Use of an FTC/TDF tail after stopping EFV was associated with the lower prevalence of subsequent NNRTI drug resistance mutation

Keywords: drug resistance; resistance mutations; HIV; antiretroviral treatment; Botswana.

Introduction

Cessation of antiretrovirals raises concerns about the potential for the development of drug-resistant viral strains, particularly for non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs). Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, such as efavirenz (EFV), have long half-lives and a low barrier to the development of drug resistance. When used in combination with other classes of drugs such as nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), staggered discontinuation using a 4-7-day 'tail' of the NRTI backbone when stopping NNRTI-based antiretroviral treatment (ART) is advised.1 This is believed to mitigate the unintended period of monotherapy with NNRTIs that ensues because of the long half-life of most drugs in this class, thus reducing the risk of developing drug resistance.2,3 There are, however, very limited data to directly support this recommendation for a tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC) 'tail': following cessation of EFV. Of note, pharmacokinetic variability (linked genetic factor - CYP2B6) in EFV metabolism between individuals has been observed, and EFV levels may be higher in persons of African descent.4 These higher drug levels may also impact risk of drug resistance when stopping EFV-based ART.

Prior to 2015, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Botswana programme for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) recommended that pregnant women living with HIV with a CD4 cell count > 350 cells/mm3 without a WHO stage 3 or 4 illness take three-drug ART in pregnancy, but discontinue the ART postpartum or upon breastfeeding cessation (option B). Although both WHO and Botswana subsequently modified guidelines to recommend lifelong ART regardless of CD4 cell count or disease stage (option B+), the prior guidance for pregnant women, as well as the inconsistent application of an NRTI tail at the time of EFV cessation, offers an opportunity to evaluate the development of resistance and the performance of a TDF/FTC tail among women stopping an EFV/TDF/FTC regimen. Because this ART regimen remains widely used throughout the world, the natural experiment afforded by prior PMTCT guidelines is applicable to our understanding of the risk of cessation of NNRTI-based regimens generally.

Methods

Study population

Between April 2014 and May 2015, we enrolled a subset of pregnant women living with HIV participating in a trial of infant cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Botswana (the 'Mpepu' study) into this resistance sub-study. Mpepu was a double-blinded randomised controlled trial designed to assess the efficacy and safety of infant cotrimoxazole prophylaxis versus placebo used daily from as early as 14 days of life through 15 months among HIV-exposed uninfected infants in Botswana.5

Women were eligible for this sub-study of drug resistance following cessation of EFV/FTC/TDF if they were living with HIV, had pre-treatment CD4 > 350 cells/mm3 without evidence of WHO stage 3 or 4 disease, initiated EFV/FTC/TDF in pregnancy and stopped ART postpartum according to Botswana guidelines at the time (at 4-6 weeks postpartum if formula feeding, or 6 weeks after weaning if breastfeeding). Per Botswana national HIV treatment guidelines, a 7-day tail of TDF/FTC after cessation of EFV was recommended. However, decisions regarding receipt and cessation of maternal ART occurred at government clinics (rather than study clinics), and the 7-day tail was inconsistently applied at the time of ART cessation.

Data collection and laboratory testing

Women eligible to participate in this sub-study were identified in the Mpepu study and scheduled for a clinic visit 4-6 weeks after ART cessation. Interested and eligible women consented to participate in the study and provided data (from self-report and medical records) on PMTCT regimen received; dates on which ART and individual antiretrovirals were started and stopped as well as provided blood specimens for drug resistance and HIV-1 RNA testing. HIV RNA results at the point of enrolment into the Mpepu study, and documented nadir CD4 counts, were retrieved and served as baseline values.

Prior to drug resistance testing, we first determined HIV-1 RNA viral load levels with the Abbott m2000sp/rt machine (limit of detection 40 copies/mL). Where HIV-1 RNA was detected, it was extracted using an automated validated technique.6 We then performed reverse transcription using in-house one-step RT-PCR technique.7 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were then purified8 and sequenced.9 Consensus sequences were generated, and the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database was used to identify all drug resistance mutations in the protease and reverse transcriptase coding regions.

Statistical methods

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 was used to perform statistical analyses, which were generally descriptive in nature; a two-sided Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate for differences in the proportion of drug resistance by the approach to ART cessation, either with a 7-day TDF/FTC tail or with abrupt cessation of all three drugs. The small number of women with drug resistance mutations precluded more detailed analysis of predictors of drug resistance.

Ethical onsiderations

The Botswana Health Research Development Committee and the Office of Human Research Administration at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health approved this drug resistance sub-study (HRDC 00732 and IRB13-2772), and women provided written informed consent for participation.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Ninety women enrolled, 74 of whom discontinued EFV/FTC/TDF postpartum and had samples collected for genetic resistance testing and are included in this analysis. Sixteen of 90 women not included in this analysis had CD4 < 350 cell/mm3 post-delivery and had to continue ART for their own health per Botswana national protocol at the time. The median time from cessation of EFV (whether or not a tail period occurred) to time sample was collected for resistance testing was 5 weeks (range: 3-13 weeks). Median age at enrolment was 29 years (range: 20-45) with median nadir CD4 count of 571 cells/mm3 (range: 361-1236). Forty-seven (64%) women had no previous exposure to antiretrovirals, 25 (34%) reported previous exposure to antiretrovirals for PMTCT purposes in a prior pregnancy and 2 (2%) were previously exposed to EFV/FTC/TDF but stopped prior to conception and then re-started EFV/FTC/TDF as three-drug prophylaxis for the index pregnancy. Thirty-two (43%) stopped ART with the recommended 1-week tail of TDF/FTC after cessation of EFV and 42 (57%) stopped all treatment at once. Of 70 women with viral load results at enrolment into the Mpepu study, 58 (83%) had HIV-1 RNA < 40 copies/mL. At 4-6 weeks post-EFV/FTC/TDF cessation, 44 (62%) of 71 women with viral load result had HIV-1 RNA < 40 copies/mL. Thirty-three (47%) women had HIV-1 RNA < 40 copies/mL at delivery and at the time of sample draw for genotyping (post-ARV cessation).

Mutations

Thirty-five (47%) of 74 samples were successfully sequenced, with 4 (11%) of 35 having a major drug resistance mutation: 2 with K103N and 2 with V106M (Table 1). All four resistance mutations occurred among women who did not receive a TDF/FTC tail (4/42, 10%), whereas no mutations occurred among 18 genotyped women who had received a TDF/FTC tail (p = 0.053). Eighteen (58%) of the 31 women who had a genotype result and no drug resistance mutation took a TDF/FTC tail. Of 39 samples that could not be sequenced, 37 (95%) had HIV-1 RNA < 40 copies/mL in the sample being tested.

Discussion

A small proportion of women stopping EFV/FTC/TDF had a major NNRTI resistance mutation detected in plasma taken a little more than a month after stopping treatment. Among women receiving a 7-day tail of TDF/FTC after stopping EFV where genetic resistance testing was able to be performed, none had detectable mutations. Our findings thus support the recommended staggered discontinuation of antiretrovirals when an EFV/FTC/TDF regimen is being stopped. Our data support prior studies that evaluated the use of an NRTI tail when discontinuing EFV-based ART.

Our observation of prolonged viral suppression < 40 copies/mL for a median of 5 weeks in 62% of women post-ART cessation was similar to findings from other studies which have demonstrated that it is not unusual for viral suppression to persist for weeks after stopping ART.10 We believe this could be because of low pre-ART viral loads in our population (because of women with less advanced disease starting ART in pregnancy).

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, our results are based on a small number of observations making generalisability challenging. Secondly, we did not report on minor drug resistance variants and, finally, more than half (63%) of women tested at a median time of 5 weeks from EFV cessation were still virally suppressed, which may suggest that we might have tested for resistance strain development early. Thirdly, we could not determine why the 7-day tail was inconsistently applied at the time of ART cessation and could therefore have missed evaluating possible confounders related to this factor.

Conclusion

Although guidelines no longer recommend discontinuation of ART after pregnancy, our study has general applicability for those requiring permanent or temporary treatment discontinuation when receiving an EFV-based regimen, informing the risk of mutation emergence in the setting of abrupt three-drug discontinuation versus discontinuing with a TDF/FTC tail. Furthermore, despite the shift to the use of newer drugs such as dolutegravir for which there is less concern about the emergence of resistance than with NNRTIs, our data are relevant to millions of individuals still on EFV-based ART (and are of particular clinical importance in regions that have access to only a limited number of antiretroviral drugs and that are also generally unable to routinely assess for drug resistance mutations before initiating a new ART regimen).

Based upon our results, we conclude that an TDF/FTC tail may help prevent selection of major NNRTI drug resistance mutations that can occur with the abrupt discontinuation of an EFV/FTC/TDF ART regimen.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the management and staff of the Botswana Harvard AIDS institute partnership for their support and to all the participants enrolled in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

S.L. was the project leader, and G.A. and S.L. were responsible for experimental and project design. G.A. and C.R. performed most of the experiments. R.L.S. and K.P. made conceptual contributions, while D.M. prepared the samples. Calculations were performed by G.A., J.L. and K.B. G.A, C.R. and S.L. co-wrote the article.

Funding information

This project was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH grant: R01HD061265.

Data availability statement

Data and associated documentation from this study will be made available for external use only under a data-sharing agreement that provides for (1) a commitment to using the data only for research purposes and not to identify any individual participant; (2) a commitment to securing the data using appropriate computer technology; and (3) a commitment to destroying or returning the data after analyses are completed.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

1.Lamorde M, Schapiro JM, Burger D, Back DJ. Antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission: Pharmacologic considerations for a public health approach. AIDS. 2014;28(17):2551-2563 https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000439 [ Links ]

2.McIntyre JA, Hopley M, Moodley D, et al. Efficacy of short-course AZT plus 3TC to reduce nevirapine resistance in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2009;6(10):e1000172. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000172 [ Links ]

3.Chi BH, Sinkala M, Mbewe F, et al. Single-dose tenofovir and emtricitabine for reduction of viral resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor drugs in women given intrapartum nevirapine for perinatal HIV prevention: An open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9600):1698-1705. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61605-5 [ Links ]

4.Sinxadi PZ, Leger PD, McIlleron HM, et al. Pharmacogenetics of plasma efavirenz exposure in HIV infected adults and children in South Africa. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(1):146-156. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12590 [ Links ]

5.Lockman S, Hughes M, Powis K, Ajibola G, Bennett K, Moyo S. Effect of co-trimoxazole on mortality in HIV-exposed but uninfected children in Botswana (the Mpepu Study): A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(5):e491-e500. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30143-2 [ Links ]

6.EZ1 Virus Mini kit v2.0, Virus Handbook. QIAGEN sample and assay technologies, USA [homepage on the Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Jul 04]. Available from: https://www.qiagen.com/cn/resources/download.aspx?id=ca13c92a-4b1b-4ced-9796-b0414a166803&lang=en [ Links ]

7.Rowley CF, MacLeod IJ, Maruapula D, et al. Sharp increase in rates of HIV transmitted drug resistance at antenatal clinics in Botswana demonstrates the need for routine surveillance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(5):1361-1366. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv500 [ Links ]

8.BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit User Guide. Thermo-Fisher scientific [homepage on the Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jul 04]. Available from: http://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/cms_081527.pdf [ Links ]

9.Applied Biosystems 3130/3130xl Genetic Analyzers User Guide. Life technologies [homepage on the Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Jul 04]. Available from: http://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/manuals/4477796.pdf [ Links ]

10.Graham TC, Aga E, Bosch RJ, et al. Brief report: Relationship among viral load outcomes in HIV treatment interruption trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;72(3):310-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000964 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Globahan Ajibola

gajibola@bhp.org.bw

Received: 19 Aug. 2019

Accepted: 16 Sept. 2019

Published: 27 Jan. 2020

Note: For editorial commentary from Prof. Gary Maartens (University of Cape Town) on this article, please see: https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v21i1.1036.

^rND^sLamorde^nM^rND^sSchapiro^nJM^rND^sBurger^nD^rND^sBack^nDJ^rND^sMcIntyre^nJA^rND^sHopley^nM^rND^sMoodley^nD^rND^sChi^nBH^rND^sSinkala^nM^rND^sMbewe^nF^rND^sSinxadi^nPZ^rND^sLeger^nPD^rND^sMcIlleron^nHM^rND^sLockman^nS^rND^sHughes^nM^rND^sPowis^nK^rND^sAjibola^nG^rND^sBennett^nK^rND^sMoyo^nS^rND^sRowley^nCF^rND^sMacLeod^nIJ^rND^sMaruapula^nD^rND^sGraham^nTC^rND^sAga^nE^rND^sBosch^nRJ^rND^1A01^nNatasha^sKhamisa^rND^1A02^nMaboe^sMokgobi^rND^1A03^nTariro^sBasera^rND^1A01^nNatasha^sKhamisa^rND^1A02^nMaboe^sMokgobi^rND^1A03^nTariro^sBasera^rND^1A01^nNatasha^sKhamisa^rND^1A02^nMaboe^sMokgobi^rND^1A03^nTariro^sBaseraORIGINAL RESEARCH

Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards people with HIV and AIDS among private higher education students in Johannesburg, South Africa

Natasha KhamisaI; Maboe MokgobiII; Tariro BaseraIII

IDepartment of Public Health, School of Engineering, IT, Science and Health, IIE MSA, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIDepartment of Psychology, School of Social Science, IIE MSA, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMédecins Sans Frontières, Rustenburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV and AIDS) is a global health and social problem, with South Africa having an estimated overall prevalence rate of 13.5%. Compared to young male participants, young female participants have been reported to have less knowledge about HIV and AIDS, including prevention strategies, and this is associated with risky sexual behaviours and negative attitudes towards condom use

OBJECTIVES: The study investigated gender differences in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards HIV and AIDS among 542 private higher education students in Johannesburg, South Africa

METHOD: Participants completed an online structured questionnaire measuring knowledge, attitudes and behaviours as well as demographics (including age, gender and relationship status

RESULTS: The results indicate that overall there were no significant differences between male and female students in terms of HIV and AIDS knowledge. However, female students had significantly less knowledge with regard to unprotected anal sex as a risk factor for HIV and AIDS. In addition, young female students reported condom use at last sex less frequently than male students. Nonetheless, both genders reported a positive attitude towards condom use and towards people living with HIV and AIDS

CONCLUSION: It is recommended that the relevant authorities at the state and the higher education level seriously consider implementing specific strategies for preventing HIV and AIDS through improved knowledge, attitudes and behaviours among young females

Keywords: attitudes about contraception; levels of knowledge; risky sexual behaviours; gender differences; young female students.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the epidemic, human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV and AIDS) has affected more than 70 million people globally, accounting for 35 million deaths.1 As of 2018, over 30% of the global HIV and AIDS prevalence has been among the youth aged 15-25 years, with 5 million young people currently living with HIV and AIDS.1 The youth between the ages of 15 and 24 years account for 45% of new infections.2 The burden of HIV and AIDS is concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, where 71% of people living with HIV reside and where 65% of new infections reported in 2017 occurred.3 The female population is disproportionately affected by HIV, with three in four new infections reported among girls aged 15-19 years, while the young female population aged 15-24 years is twice as likely to be living with HIV and AIDS than their male counterparts.4

South Africa is known to have one of the highest rates of HIV and AIDS globally and on the African continent. It is estimated that 7.97 million South Africans (13.5%) are living with HIV and AIDS, and over a fifth of these are females of reproductive age (15-49 years). Gauteng Province, the most populous province in the country (25.8% of the population), is home to over 2 million young people, the majority of whom are females.5 The high infection rate among the young female population is attributed to a lack of knowledge as well as poor attitudes towards the use of condoms and risky sexual behaviour.6 Knowledge regarding HIV and AIDS infection is necessary to correct negative attitudes towards condom use and to encourage healthy sexual behaviour among the youth by improving their ability to practice safe sex. This is likely to improve the uptake of HIV prevention strategies to address the increase in the prevalence of HIV and AIDS in vulnerable populations.6,7 Young female participants are twice as likely to be infected with HIV and AIDS, compared to young male participants, with the most common means of transmission being unprotected sex, and the key barriers to prevention being lack of knowledge, negative attitudes and risky sexual behaviour.3,6,8

Knowledge facilitates familiarity with and awareness of HIV and AIDS, which influences attitudes (resulting in support and motivation for prevention) as well as behaviour (safer sex practices), thereby reducing the risk of infection.9 A high prevalence of HIV and AIDS is associated with lower levels of knowledge about the modes of transmission and condom use, negative attitudes towards condom use and risky sexual behaviours such as unsafe sex and multiple sex partners.10,11 The young female population has been shown to possess significantly lower levels of knowledge as well as misconceptions and erroneous beliefs about HIV and AIDS, compared to the male population.6,12 This is often associated with negative attitudes to prevention strategies, which have been shown to affect behaviours such as condom use.13 Studies have also confirmed that HIV and AIDS testing attitudes and the intention to use condoms are influenced by knowledge.14,15

Charles et al.16 reveal that although the young female population is more concerned about HIV and AIDS infection, they agree less than the young male population on condom use as a safe sex strategy. The attitudinal gender differences of the young female population with regard to transactional sex are thought to result in risky behaviours such as unprotected sex with older men.17

Although it is known that the young female population is more susceptible to HIV and AIDS infection, there is a paucity of research on gender differences in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours among young people in higher education settings, thereby inhibiting an in-depth understanding of factors contributing to HIV and AIDS infection among this population in South Africa. Such a gap in the literature negatively influences policy and practice aimed at reducing HIV and AIDS rates among vulnerable youth within this context. This study was aimed at identifying gender differences in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours among the youth at a private higher education institution in Johannesburg, South Africa. It is envisaged that this will allow for the development of specific strategies for preventing HIV and AIDS infection among the youth at private higher education institutions in South Africa. The research question seeks to determine differences between the male and female populations on knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards HIV and AIDS. It is hypothesised that knowledge, attitudes and behaviours will differ between the male and the female populations.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional survey was conducted at a private higher education institution in Johannesburg, South Africa. Participants were invited via an online learning platform where they completed and submitted a structured questionnaire assessing sexual risk and sexual prevention behaviours.

Setting

Johannesburg is the capital of Gauteng province and is considered the largest and the wealthiest city in South Africa. With a population estimated at 5.6 million, it is the most populous city in the country, with 66% growth rate in population expected over the next 30 years. Racial profiles indicate that 76.4% of the population is black African, 5.6% is mixed race, 12.3% is white or of European descent and 4.9% is of Indian or Asian descent. Approximately, 7% of the population is illiterate, 3.4% have only a primary education, 41% have completed secondary education and 6% have a tertiary qualification.18

Study population and sampling

Random sampling was used to recruit 845 students enrolled at a private higher education institution in Johannesburg, South Africa. Random numbers were generated using a computer program to select participants from the sampling frame - enrolment records. A global email was sent to all potential participants inviting them to participate in the study. Of those invited to participate in the study, 542 responded - a response rate of 64%. Participants completed an online questionnaire via their online learning platform, which contained study information and instructions for accessing and completing the questionnaire.

Data collection and analysis

An online structured questionnaire measuring knowledge, attitudes and behaviours as well as demographics (including age, gender and relationship status) was completed by the participants. The questionnaire was developed as part of a larger study using existing literature and consisted of 93 questions of which 51 questions were on knowledge about HIV and AIDS transmission and prevention, attitudes towards HIV and AIDS, including treatment and prevention methods (six questions), and sexual behaviours (36 questions).

Data were cleaned and checked for errors before coding and analysing using STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). To evaluate knowledge and behaviours, respondents were required to provide mostly 'yes' or 'no' responses. For the knowledge score, a score of 1 was assigned for a correct answer and 0 for a wrong answer. For the attitude questions, a rank was assigned using the Relative Importance Index to obtain an overall rank for each attitude item. For knowledge, attitudes and practice questions (knowledge and awareness of HIV & AIDS, prevention and control of HIV, students' attitudes towards condom use and people living with HIV, risky sexual behaviours), the frequency of responses in each category was determined. A chi-square test was used to evaluate the variation in knowledge, attitude and behaviour between male and female students. For all tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) (approval number CF15/1095 - 2015000518). No identifying information was obtained from students when they completed the questionnaire. A unique identifier was generated when the questionnaire was submitted. All the data were de-identified for analysis. Data were stored in password-protected files and will be retained for up to 5 years after the study.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the students

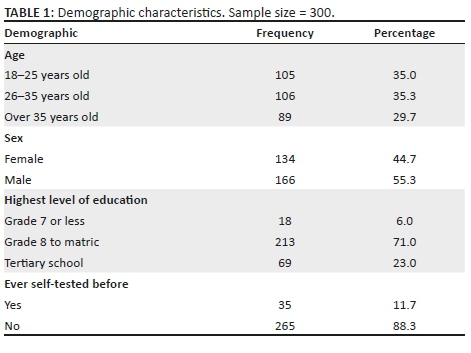

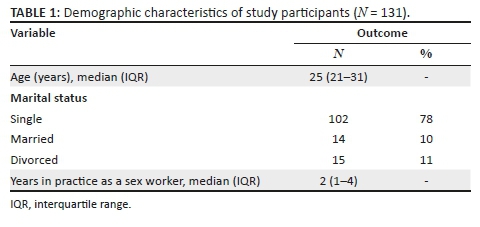

Data were collected from 542 students, 374 (69.0%) of whom were female students. The participants had a median age of 19 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 16-30 years), and their average knowledge score of HIV and AIDS and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) was 0.78 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.17); 397 (73.2%) students were black Africans, 67 (12.4%) students were whites, 44 (8.1%) students were of Indian/Asian descent and 29 (5.4%) students were of mixed race; 427 (80.6%) students were single and 88 (16.6%) students were in a stable relationship. Most of the students were in the Higher Certificate, Higher Education Studies' stream (n = 357, 71.1%), and 145 (28.9%) students were undergraduates (Table 1).

There were high levels of awareness and knowledge about biomedical methods of HIV prevention amongst the sample group. More female (77.1%) than male students (64.1%, p = 0.003) said that they had heard about medication that HIV-positive pregnant women could take to reduce the risk of infecting the baby with HIV, and more female (59.9%) than male students (47.6%, p = 0.015) had heard about medication that could help to reduce the risk of HIV infection if a woman had been raped. A higher proportion of male (95.8%) versus female students (85.7%, p = 0.001) said that they were able to obtain a condom. There was no significant difference between the proportion of male (97.0%) and female students (94.1%) about where to get condoms (Table 2).

Knowledge about HIV transmission was high, with 98.1% of female students and 96.4% of male students knowing that the virus could be passed on through unprotected sex. A high proportion of male students (92.9%) and female students (90.9%) knew that a person can have HIV and pass it on to others without showing symptoms. Also, most female students (77.4%) and male students (76.8%) knew that STIs put people at greater risk of HIV infection. However, only 33.6% of female students and 39.3% of male students admitted that they knew that anal sex increased the risk of HIV infection. A low proportion of female students (16.9%) and male students (21.4%) knew that people can reduce their chance of getting HIV by using a condom every time they have sex. More female (96.2%) than male students (91.7%) were aware that AIDS could not be cured. Most of the female students (n = 307, 82.5%) and male students (n = 119, 70.8%) indicated that partners could not have sexual intercourse if both partners were HIV-positive (p = 0.002) (Table 3).

As illustrated in Table 4, a substantial number of students expressed positive attitudes towards condom use. Across age and gender groups, a significant majority of students disagreed with the statement that a woman loses a man's respect if she asks him to use a condom (96.8% of female participants and 91.7% of male participants); that they only use condoms if their sexual partner wants to use them (95.7% female participants and 86.3% of male participants); and that condoms should only be used if having sex with a person who is not the main sexual partner (94.6% of female participants and 83.9% of male participants). About a third of the students and 41.7% of the male students said that condoms felt unnatural, and nearly a quarter of the students aged 20-32 years and 36.3% of the male students said that condoms alter climax or orgasm.

Most participants had positive attitudes towards HIV-positive people, but 38 (7%) participants were unwilling to be associated with or share living space with people living with HIV. Based on the relative importance index score, the most important attitudes towards people living with HIV, ranked in order of relative importance, were: (1) About 83.4% of students indicated that even if a family member had HIV, their relationship with them would remain good; (2) 20% of students said that sharing a house with HIV-positive people would be very difficult for them; and (3) 7.6% of students felt that people who get infected with HIV are promiscuous. Forty-one (7.6%) students also said they do not want to be associated with HIV-positive people, and 6.4% of students felt that HIV-negative people should not be allowed to socialise with HIV-positive people. Students had positive attitudes towards treatment for HIV and AIDS. Around two-thirds (63.1%) of the students agreed that HIV treatment would keep an HIV-positive person alive (ranked the most important attitude). Two hundred and seventy-four (50.8%) students agreed that HIV medication really works (with a relative importance score of 2). Most of the respondents (69% students) rejected the notion that antiretroviral (ARV) medication is poisonous (Table 5).

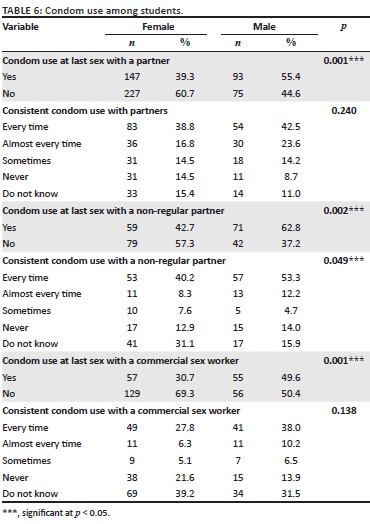

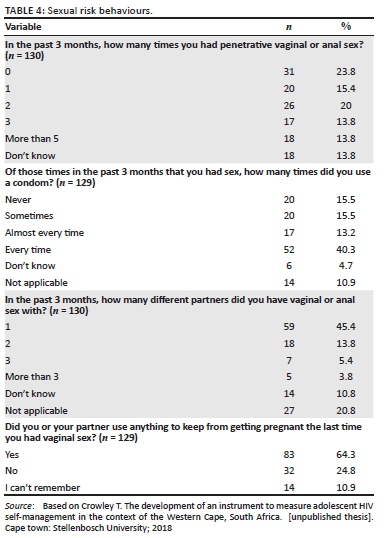

Condom use at last sex was higher when with a regular partner: female students (n = 147) and male students (n = 93). The difference is statistically significant (p < 0.001). Fewer female students (n = 53) and male students (n = 57) reported using condoms consistently with a non-regular partner (p = 0.049). More female students (n = 83) reported consistent condom usage (every time) with regular sex partners than male students (n = 54); however, the difference was not significant (p = 0.240) (Table 6).

Discussion

South Africa is battling an HIV and AIDS pandemic, which remains one of the primary social and health concerns in the country. Notwithstanding the outstanding effort by the Department of Health in implementing HIV and AIDS prevention strategies, South Africa is still the country worst affected by the HIV and AIDS pandemic, with the youth between the ages of 15 and 24 years being the hardest hit.5 Young female students are reported to have higher infection rates owing to a lack of knowledge and poor attitudes towards condom use and risky sexual behaviours,6 making them twice as likely as male students to be infected with HIV.3,6,8 This study was aimed at determining gender differences in knowledge, attitudes and behaviour in relation to HIV and AIDS among students at a private higher education institution in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Findings in this study indicate that there is no significant difference between male and female students in terms of their general knowledge of HIV and AIDS. However, it is noteworthy that female students had significantly less knowledge of unprotected anal sex as a risk factor for HIV and AIDS. In addition, a smaller proportion of female students reported condom use at last sex, compared to their male counterparts. This could be attributed to the female population having limited control over male condom usage.19 The complex power imbalance in this scenario, with most females not having the power to negotiate condom use with their partners, is the likely underlying cause.20,21

Moreover, 8.3% of male students and 3.8% of female students believed that AIDS can be cured. Although these percentages are comparatively low, they are equally as disconcerting as the results in Haroun et al.,22 who found that just over 20% of a sample of university students in the United Arab Emirates did not know whether HIV and AIDS could be cured or not. This poor knowledge of basic messages relating to HIV and AIDS is a likely reason as to why the youth engage in risky sexual behaviour and why the prevalence of HIV infection among them is high.23

Regarding risky sexual behaviour, this study revealed notable differences between male and female students, with the latter (57.3%) and the former (37.2%) reporting not having used a condom at last sex with a non-regular partner. As the chi-square test revealed no significant variation in attitudes between male and female students, we opted to investigate the entire sample's attitudes rather than to compare male and female students. Results revealed that the majority of participants (83.4%) had a positive attitude towards people living with HIV and AIDS. This differs from previous findings where the majority indicated negative attitudes towards people living with HIV and AIDS.22 Positive attitudes such as these have been attributed to parental and social communication aimed at promoting HIV and AIDS awareness among the youth.24

Limitations

There were a disproportionate number of female students, compared to male students in this study. It is possible that this might have affected the robustness of the chi-square test and therefore skewed the findings. In addition, the sample came from one private higher education institution in Johannesburg, South Africa. It would have been ideal for more institutions to be included in the study to get a better picture of the knowledge levels, attitudes and behaviours towards HIV and AIDS at private higher education institutions in the Johannesburg metropolitan area. Notwithstanding these limitations, these findings could serve as a springboard for national research that would be more representative of the wider student population in both private and public higher education institutions.

Recommendations