Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.15 no.4 Pretoria dic. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2023.v15i4.1687

RESEARCH

Perceptions and experiences of employers and mentors of graduate optometrists' practice readiness in South Africa

T PutterI; D van StadenII; A J MunsamyII

IMOptom, BCom ; Discipline of Optometry, School of Health Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban, South Africa

IIPhD (Optometry) ; Discipline of Optometry, School of Health Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Optometry graduates are a key source of new recruits for private practice employers, the largest employer of South African (SA) optometry graduates. Universities should ensure that graduates are employable to compete in the labour market and to practise.

OBJECTIVE. To gain an understanding of the practice readiness of optometry graduates who qualified from SA institutions between 2016 and 2020, from the perspective of private practice employers and mentors (EMs).

METHODS. Using non-probability convenience sampling, private optometry EMs of recent graduates were invited to complete an online questionnaire designed around the core competencies for health professionals in SA. Quantitative data retrieved from a five-point Likert scale were analysed employing SPSS software, using the one-sample t-test, factor analysis and Cronbach's alpha.

RESULTS. EMs (N=28) felt that graduates showed satisfactory competence in theoretical knowledge, communication, collaboration and professional skills, but weaknesses in aspects of clinical skills, leadership and management skills, and health-advocacy skills. The specific areas of weaknesses identified were dispensing skills, leadership, handling of criticism, handling of stress, implementing processes to improve services, industry awareness and practice management. All questions, except two questions for scholarly and professional skills, had an acceptable level of reliability.

CONCLUSION. Practice readiness was viewed favourably by EMs for optometry graduates, but the specific weaknesses identified in the curriculum include stakeholder involvement from private employers. Increasing the diversity of clinical hours, including rotations in private practices, as well as facilitating and promoting work-based learning may strengthen practice readiness.

Optometry graduates are expected to have a level of technical and discipline-related competencies upon graduation. However, employers require graduates to demonstrate a broader range of soft skills and attributes, including team-working, communication, leadership, critical thinking, problem-solving and managerial abilities.[1] Hard skills are occupation specific and well defined, whereas soft skills are transferable between occupations. In addition to developing discipline-based knowledge, there is a need to develop soft skills at universities.[2]

Evidence from non-healthcare fields identifies the attributes and characteristics that define employability skills. Few studies have focused on employability skills or practice readiness within the health sector. The Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) adopted the CanMEDS Physicians Competency Framework to formulate seven core competencies for undergraduate students in clinically associated, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa (SA) in 2014. Therefore, to assess the practice readiness of optometry graduates, these seven core competencies, including being a healthcare practitioner, communicator, collaborator, leader and manager, health advocate, scholar and professional, were used.[3] Whether graduate optometrists meet these competencies has not been evaluated.

Optometry sectors (private v. public) have different contexts and job demands; however, these revolve around the central function of providing quality eye care.[2] This study focused on optometry in the private sector, as the majority of SA optometry graduates are employed by private practitioners.[2] Engaging with private practice employers and mentors (EMs) helps to align academic programmes with the employers' needs so that graduates may secure employment, while ensuring better patient health outcomes.[4]

To date, no research has been conducted to examine the views of EMs who guide and play an oversight role in the graduate optometrist's transition from university to the real world. The aim of the study was to investigate the perceptions and experiences of private EMs of recent optometry graduates regarding their practice readiness, to help SA universities better understand the real-world concerns of EMs.

Methods

The study was descriptive, cross-sectional in design. It was conducted using a structured closed-ended online questionnaire, guided by the research question:

• 'Are graduate optometrists who completed their training at South African institutions between 2016 and 2020 considered practice ready by employers and mentors?'

Using non-probability convenience sampling, SA private practice EMs who had played an oversight role in the work of a graduate optometrist during the 5 years preceding the study (2016 - 2020) were invited. A mentor was considered an experienced and trusted advisor. Data were collected from EMs employing graduates from various universities at a point in time. The graduate optometrists should have graduated from one of the four universities in SA that offer a Bachelor's degree in optometry, to provide a representative cross-section.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Humanities and Social Science Research and Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban (ref. no. HSSREC/00001635/2020) before commencement of the study. A hyperlink for the questionnaire was sent via email to private practice optometrists in SA, posted through professional network platforms. Informed consent was obtained from EMs by accepting the declaration on the first page of the online questionnaire.

Data collection

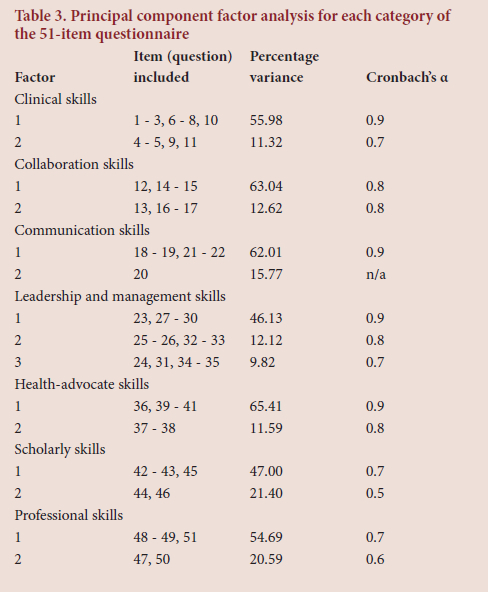

Quantitative data were obtained by asking participants to answer 51 questions using a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree). Participants also provided personal concerns regarding their perceptions of graduate practice readiness. The questionnaire was first piloted on 5 EMs to ensure it met the study objectives. The questionnaire was based on the abovementioned exit-level competencies as described by the HPCSA.[3] Principal component factor analysis was used for each of the seven categories to measure validity. All questions, except questions 44 and 46 (Cronbach's alpha 0.5) for scholarly skills, and questions 47 and 50 (Cronbach's alpha 0.6) for professional skills, had an acceptable level of reliability.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS software, version 27 (IBM Corp., USA). A one-sample t-test was used to determine whether the sample mean (%) per question was statistically different, and all p-values reported were tested at α=0.05 level.

Results and discussion

Twenty-eight EMs responded to the survey. Table 1 presents results for each of the seven categories surveyed in the study questionnaire. Only statistically significant observations (p<0.05) from a one-sample f-test are reported. Table 2 indicates individual concerns of EMs relating to the practice readiness of optometry graduates in SA. Table 3 shows the principal component factor analysis for each category of the 51-item questionnaire.

Clinical skills

Strengths identified from the survey of clinical skills included the graduates' ability to identify and respond appropriately to ethical issues arising during patient care (53.6% agreed; p<0.001), to perform an effective three-way handover (53.6% agreed; p<0.001) and to adapt to new techniques and instrumentation (57.1% agreed; p=0.001).

However, EMs felt that graduates did not have adequate dispensing knowledge (39.3% disagreed; p=0.103), further supported in the open-ended comment section by 5 participants. This result is in agreement with that of Oduntan et al.,[5] who found that 23.8% of graduates also thought they were least prepared for dispensing.

While the majority of participants reported that graduates had satisfactory clinical knowledge (39.3%; p=0.024), a possible skills gap was raised. Four participants specifically commented that, although graduates were well educated in the theoretical aspects of optometry, they needed a more holistic approach to eye care. Linking theory to practice requires clinical exposure and adopting case-based learning approaches.[2] EMs suggested that graduates would benefit from more real-world experience during training. Work-based learning is an excellent strategy, providing students with experience to apply academic and technical skills in a professional setting. SA universities offer little or no private sector clinical rotations, which may account for this concern of EMs.

Communication skills

Most participants agreed that graduates have good, clear and empathic communication skills (64.3% agreed; p<0.001). While many EMs agreed that graduates are confident and appear comfortable interacting with patients (39.3% agreed; p=0.024), this percentage is low and possibly indicates a weakness that requires addressing. Communication skills is an important soft skill across the healthcare sector. Effective communication improves treatment adherence and overall patient satisfaction.[6] The use of peer role-playing scenarios and role-playing sessions with simulated patients, case studies, video recordings of optometry patient communication, structured feedback after encounters with patients and observing experienced optometrists in practice may be helpful teaching methods.[6]

Collaboration skills

The majority of EMs agreed that graduates were able to collaborate with their colleagues and patients, displayed competence in team-meeting participation and respecting team ethics (64.3% agreed; p<0.001), and establishing trust and rapport with colleagues and supervisors (53.6% agreed; p<0.001). However, participants had less confidence with regard to questions surrounding conflict management (35.7% agreed; p=0.037). Some participants believed graduates were unable to resolve conflicts with colleagues and patients appropriately. Other health-sector studies identified gaps in conflict-management skills among graduates.[7] Context-specific conflict management in the curriculum might be a gap in university training.

Leadership and management skills, and graduate health-advocate skills

The lack of consensus among participants in terms of leadership and management skills, suggests variability among graduates; therefore, more data are required. While graduates are reportedly able to manage new situations and adapt (60.7% agreed; p<0.001), they are perceived to be less able to handle criticism (42.9% neutral; p<0.001) and stressful situations (42.9% neutral; p<0.001), deliver effective staff training (64.3% neutral; p<0.001) and show a willingness to lead and take charge (39.3% neutral; p=0.067).

The transition from university to the real working environment is challenging for graduates. Maintaining appointment times, clinical issues, workload demands and management tasks were the factors most frequently associated with stress.[8] Universities should formalise stress education and management strategies within the curriculum.[7] Private practice externships may provide students with valuable perspectives regarding expectations in the workplace.[9]

Time and eye care service-management skills (39.3% agreed; p=0.067) were also flagged as possible concerns, as well as taking an interest in organisational affairs (39.3% agreed; p=0.067). Rampersad[2] found that, although optometry graduates learnt time-management skills along with experience, they felt that the consultation times were much shorter than those during training. Teaching how to tailor consultation times to the patient's presenting needs may be useful.

The participants differed in their opinions regarding the capability of graduates to solve everyday practice-related problems in an effective and efficient manner (46.4% neutral; p=0.009). Industry awareness and business/practice management principles (39.3% disagreed; p=0.067) were identified as possible weaknesses among graduates. Rampersad[2] found that optometry graduates felt that they were not prepared for the administrative and commercial aspects of optometry. Three participants specifically raised concerns about inadequate practice-management skills.

Most participants agreed that graduates were able to think beyond the individual patient's eye health needs (57.1% agreed; p<0.001) and understand the importance of eye health as a component of healthcare (53.6% agreed; p<0.001).

Scholarly skills

Most participants agreed that graduates had adequate scholarly skills in all areas, except being able to source the relevant research, critically appraise it and apply it in practice (39.3% neutral; p=0.013). Evidence-based practice and critical thinking are important skills for practice readiness or work readiness,[10] and time should be set aside for continuing education.

Professional skills

Participants believed graduates displayed strengths in professional behaviour, ensuring a professional practice setting (42.9% agreed; p=0.004), maintaining appropriate professional relations (71.4% agreed; p<0.001) and adhering to appropriate legal and ethical codes of practice (57.1% agreed; p<0.001).

Study limitations

The study had a relatively low response rate. Group interviews may have improved the observations. EMs might differ in their opinions about graduate practice readiness owing to the location, culture or nature of their individual practice. However, no such distinction was made in this study. EMs were not asked to disclose how many years of experience their graduates had; therefore, no relationship could be drawn between years of experience and areas of weaknesses.

Conclusion

Graduate optometrists' strengths lie in theoretical knowledge, communication, collaboration and professional skills. Their weaknesses lie in aspects of clinical, leadership and management, and health-advocate skills. Current training programmes may not satisfy all professional requirements for the private sector. Findings may help universities better understand the factors affecting recent graduates' transition into the workforce to ensure an improved preparedness for the workplace. Diversity of clinical hours, including private practice externships, as the current major employer of SA graduate optometrists, may improve work-based learning in the curriculum. Furthermore, including employers and experienced optometrists in the ongoing design and delivery of the optometry course will help to ensure that training aligns with the evolving needs of the industry.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. DvS and AJM are University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Developing Research Innovation, Localisation and Leadership in South Africa (DRILL) fellows. DRILL is an NIH D43 grant (D43TW010131) awarded to UKZN in 2015 to support a research training and induction programme for early career academics. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of DRILL and the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions. All authors constructed, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Lowden K, Hall S, Elliot D, Lewin J. Employers' Perceptions of the Employability Skills of New Graduates. London: Edge Foundation, 2011. [ Links ]

2. Rampersad N. Graduates' perceptions of an undergraduate optometry program at a tertiary institution: A qualitative study. MEd degree. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2010. https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/hande/10413/5154/Rampersad_Nishanee_2010.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed 14 July 2023). [ Links ]

3. Medical and Dental Professions Board. Core competencies for undergraduate students in clinical associate, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa. 2014. https://www.chs.ukzn.ac.za/Libraries/News_Events/MDB_Core_Competencies_-_ENGLISH_-FINAL_2014.pdf (accessed 3 March 2022). [ Links ]

4. Spaulding S, Martin-Caughey A. The goals and dimensions of employer engagement in workforce development programs. 2015. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/76286/2000552-the-goals-and-dimensions-of-employer-engagement-in-workforce-development-programs_1.pdf (accessed 3 March 2022). [ Links ]

5. Oduntan AO, Louw A, Moodley VR, Richter M. Perceptions, expectations, apprehensions and realities of graduating South African optometry students. S Afr Optom 2007;66(3):94-108. https://doi.org/10.4102/aveh.v66i3.241 [ Links ]

6. Hausberg MC, Hergert A, Kröger C, Bullinger M, Rose M, Andreas S. Enhancing medical students' communication skills: Development and evaluation of an undergraduate training program. BMC Med Educ 2012;12(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-16 [ Links ]

7. Merga M. Gaps in work readiness of graduate health professionals and impact on early practice: Possibilities for future interprofessional learning. Focus Heal Prof Educ Multidiscip J 2016;17(3):14-30. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v17i3.174 [ Links ]

8. Long J, BurgessHLimerick R, Stapleton F. What do clinical optometrists like about their job? Clin Exp Optom 2013;96(5):460-466. https://doi.org/10.1111/cxo.12017 [ Links ]

9. Goetz JW, Tombs JW, Hampton VL. Easing college students' transition into the financial planning profession. Financ Serv Rev 2005;14:231-251. [ Links ]

10. Casner-Lotto J, Barrington L. Are They Really Ready to Work? Employers' Perspectives on the Basic Knowledge and Applied Skills of New Entrants to the 21st Century US Workforce. Washington DC: Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2006. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519465.pdf (accessed 4 March 2022). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

T Putter

tlputter@gmail.com

Accepted 17 May 2023