Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.15 no.2 Pretoria Jun. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2023.v15i2.1638

RESEARCH

Peer learning model in speech-language pathology student practicals in South Africa: A pilot study

K CouttsI; N BarberII

IPhD; Department of Speech-Language Pathology, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIMA; Department of Speech-Language Pathology, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Given the current challenges of decreased clinical resources and the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on clinical training at sites, a shift in teaching models for practical placements for speech-language pathology (SLP) students in South Africa (SA) was required. The peer learning model that has been trialled in the physiotherapy and nursing professions was piloted for this cohort of students to combat these restrictions

OBJECTIVES: To determine whether the peer learning model is an optimal supervision framework for final-year SLP students in the SA context for the adult neurology practical

METHODS: This was a qualitative study that used a cohort of final-year SLP students. Once ethical clearance was obtained, data collection commenced using various instruments, including self-reflection tools, questionnaires and pre- and post-interviews. Data were analysed using a top-down approach whereby themes were generated and then further analysed

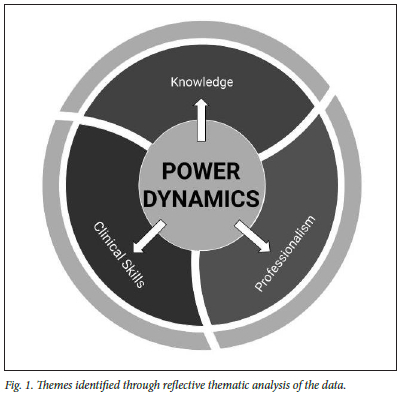

RESULTS: Four themes emerged: power dynamics, theoretical skills, clinical skills and professionalism. Power dynamics was a novel finding of this study and showed how a shift in power dynamics can facilitate the development of clinical skills. Peer learning appeared to improve clinical integration and clinical skills, including clinical writing and self-reflection

CONCLUSIONS: The piloting of the peer learning model appeared to be a success for final-year SLP students in an outpatient adult neurology setting. The findings from this study can assist in furthering studies in this context

Speech-language pathology (SLP) is a diverse field and graduates can work in research, academia, education and healthcare.[1] In South Africa (SA), there are contextual challenges to student placements and a need for pedagogical shifts for the manner in which SLP students are trained to better enhance critical thinking and self-reflection skills. These skills are needed to ensure that SLP graduates become lifelong learners.

From a contextual standpoint, in SA there are currently 2 643 SLPs registered with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA).[1] Not all of these SLPs work at sites that can accommodate students. Therefore, there is a high student-to-clinical educator (CE) ratio at these various training sites. Anecdotally, the current sites in Johannesburg are unable to accommodate students owing to the high student-to-CE ratio together with their existing workloads. This is particularly true for government hospitals and clinic settings. The limitations of COVID-19 restrictions have further complicated this situation. These circumstances create challenges for sites to accommodate students and increase the workload for existing CEs. A viable long-term solution is therefore required to address this problem.

From a pedagogical perspective, the traditional supervision model requires one CE per site, who is responsible for the student marking, feedback and teaching. This model is cumbersome for the CE, especially given the high number of students per site. It also follows the more pedagogical approach towards teaching,[2] as the CE is expected to be the sole knowledgeable other, which can be problematic.[2] This approach to teaching does not engage the learner as an active participant. Anecdotally, an example would be the tutorials that are run at the practical sites, which are often CE driven. This method of teaching should also be changed. The current gap is therefore both contextual and pedagogical in nature.

The use of the traditional teaching model and the situation of CEs being overworked are not unique to the SA setting. The nursing profession in Europe and the physiotherapy profession in Australia experience similar challenges and use the peer learning model as a potential solution to offset these challenges.[3,4] The peer learning model is based on the social learning theory,[5] whereby students need to develop insight into their own performance and need to avoid the one-way learning directive that is often seen in the current traditional methods of supervision. The peer learning model can potentially address the abovementioned practical and pedagogical challenges. Peer learning requires a collaborative approach to supervision.[61 Students take a more active role in their learning using this model and the CE serves increasingly as a mentor.[6]

Objectives

The aim of this pilot study was to determine whether the peer learning model is an optimal supervision framework for final-year SLP students in the SA context when conducting an adult neurology practical.

Methods

This was a qualitative study that used a purposive sampling method. There were 15 final-year SLP student participants from one site over two semesters, which was deemed appropriate, as this was a pilot study. The sample was taken from the cohort of 24 final-year students. The site was chosen because the principal investigator (PI) was the primary CE for this practical rotation and could therefore oversee and enforce the teaching methodology of the peer learning model. There was a group ratio of 7/8 students to 1 CE, which reflected the contextual challenges that this peer learning model aimed to address.

As the PI conducted the practical, a research assistant (NB) helped with data collection and analysis to remain neutral, prevent bias and reduce power dynamics between the participants and the PI. The research assistant was trained on the data collection methods and the study objectives, which improved the trustworthiness of the results.

Before the practical started, the students were provided with the study information letter. If they chose to participate, they were then sent the links to the questionnaires using an online platform. They gave online consent before starting the questionnaire. In this manner, the researcher was unaware of which students wanted to participate. An online platform allowed their answers to remain anonymous and was used owing to COVID-19 regulations at the time. The PI and the research assistant had access to the answers. The same process was followed with the questionnaires at the end of the practical. The students then voluntarily submitted their contact details to the research assistant if they chose to participate in the focus group discussion. The PI was not involved in this process. The research assistant conducted and transcribed the interviews independently so that these would remain anonymous to the PI. The PI also used their peer feedback as a data collection tool.

For the practical, students worked in pairs and reviewed each other's therapy plan before submitting it to the CE. Each student had their own patient and the other student was allowed to assist when necessary. At the start of each block, the CE changed the pairs for students to learn from different peers and patients. The CE gave feedback to the students based on the departmental rubric, including knowledge, skills and professionalism. The students also gave verbal and written feedback to each other at the end of each session.

The qualitative data were obtained from the following sources: the peer feedback, pre-questionnaires, post-questionnaires and post-semi-structured interviews. The self-developed questionnaires consisted of closed- and open-ended questions centred around experiences of previous teaching models with CEs. The content of the pre-questionnaire focused on achieving the study aims by exploring the challenges and benefits that the students experienced over their previous years of study with different teaching styles at their various training sites. Their experiences related to the learning styles that worked best and those that did not work well for them in a clinical setting. The post-questionnaire explored student experiences around the peer learning model but followed the same questions as the pre-questionnaire. These questions included if they felt that they had benefited or not - they needed to expand on the answer. They also needed to comment on the time commitments of this method compared with other practicals. Moreover, participants had to comment on potential changes that they would want to make to the running of the peer learning practical to improve their clinical experience and learning opportunities. As this was a pilot study, the tools were examined for reliability and validity of being able to answer the research aims and objectives. The questions were deemed appropriate by both the researcher and the research assistant, as the participants were able to answer the questions sufficiently and the aims of the study were able to be met based on the insights of the participants. The answers from the questions were reviewed by the PI and the research assistant so that the questions for the semi-structured interview could be developed. There was also a discussion around which themes needed more clarification and depth for the interview. The interview questions followed the same theme as the questionnaires. The coded transcripts from the interview were reviewed by both researchers during the data analysis process for theme development to ensure that co-coding occurred. This procedure further assisted in the trustworthiness process. The results revealed that the face and content validity of the tools was appropriate as the study aims were met. These tools can therefore be used in a larger study.

The data from all three data collection tools were analysed thematically using a top-down approach. Braun and Clarke's[7] six-step level of analysis was followed.

Method and data triangulation was employed as the researchers used questionnaires, interviews and peer reflection notes, which improved the rigour of the results. Although the data collection tools were different to those in the Sevenhuysen et al.[3] study, the methodology of the questionnaires, focus group and reflections, as suggested by Sevenhuysen et al.[3] for the physiotherapy students, was used for this study, as it was proven to be reliable.

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Non-Medical) (ref. no. M210228).

Results and discussion

The objective of this study was to understand if the peer learning model was an optimal supervision framework for final-year SLP students in the SA context when conducting an adult neurology practical. This model showed practical benefits, but the pedagogical aspects became more significant and are therefore reported. These themes were identified from the pre- and post-questionnaires and the focus group. Although 15 students participated in the questionnaires, only 6 participated in the focus group.

The central and novel theme identified from the three sources of data was power dynamics, as it interacted with and impacted on other identified themes, i.e. knowledge, clinical skills and professionalism. Fig. 1 illustrates the centrality of the theme of power dynamics and how the other themes are impacted by it.

Theme 1: Power dynamics

Power dynamics between the CE and the students and between the students in their peer groups were pervasive throughout the other themes of knowledge, skills and professionalism, which is discussed below. In the traditional model, participants perceived CEs as individuals with 'expertise to help', as explained by participant 1. Statements from the pre-practical questionnaire also reflected on the role of the CE to facilitate learning, guide, support and help the students identify strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, these statements consolidate the notion of the CE being the knowledgeable other that transfers knowledge to the student, perpetuating the unequal power dynamic in the CE-student relationship:

'Some were very rigid and they want you to adapt to what they think and how their style is instead of enhancing the student style and allowing you to develop your own style.' (Participant 6)

'You just going off what your supervisor wants and their strict way instead of exploring multiple ways of doing therapy.' (Participant 2)

'I get quite anxious when the supervisor is there and I don't perform my best.' (Participant 2)

These reflections from participants 2 and 6 and comments from the questionnaires confirm that the CEs' perceived power often originates from multiple sources, including their role and/or title, their knowledge base and their clinical expertise.[8]

Students perceived less disparity in the power dynamics in the peer learning model. A social constructivism perspective of learning was promoted through dialogue and collaboration rather than hierarchical structures. Social constructivism recognises that knowledge evolves over time and that learning occurs through language, particularly dialogue, to facilitate collaboration and knowledge construction.[9] In the post-practical questionnaires and in the focus group, participants provided statements to substantiate their collaborative learning in a peer learning model. Below are a few examples to substantiate this change in power dynamics:

'I found it a lot more beneficial in terms of engaging a lot more with cases with my peer.' (Participant 2)

'It is so nice to have someone to talk to and you know someone to bounce ideas off and share opinions and get their opinions. (Participant 3)

'I think it makes it a bit more comfortable speaking to them [peers] as you know they have the same level of knowledge as you do. They do not have any kind of expectations of you so it's much easier for me.' (Participant 6)

'You're comfortable with your peers, they're approachable ... it's easy to come to them with ideas and ask for insights.' (Participant 3)

The shift in power dynamics is evident in the peer learning model and how social constructivism supports the learning experience for students. It enables students to have a richer learning experience, as they are able to collaborate and learn in an environment with potentially less hierarchical structures and power dynamics. Dialogue was identified as a key element to the change in power dynamics, highlighting how the students use language and dialogue to construct knowledge and in turn develop clinical skills.

Theme 2: Knowledge

This theme encapsulates the reflection that students were able to increase their theoretical knowledge through collaboration. In both the questionnaires and the focus group, participants reflected that in the traditional model, CEs often expected students to have in-depth theoretical knowledge of disorders despite CEs encouraging students to be lifelong learners. A student's learning is reliant on whether the CE has sufficient knowledge in that particular area of expertise. The expectation of CEs and the perception of participants that CEs are knowledgeable others, further consolidate the hierarchical power dynamics of the traditional model and support the need to shift teaching models:

'Supervisors expect a certain level of knowledge and what they think you should know and what they assume you would be able to do by a certain year.' (Participant 6)

'So if you have a supervisor who has come to do a specific adult supervisor session, whereas they are actually focused on child language in their real daily life, and they're not quite sure what they're doing when it comes to working with adults, then the supervision that you get given is very limited.' (Participant 1)

Participants reflected that in the peer learning model, they were exposed to more knowledge as they read other session plans, reports and discussed a variety of cases:

'So in this way it will increase your exposure and your knowledge because you're going to be seeing your partner's report, you're going to get to see all of their sessionals and you're also going to be watching all of their sessions.' (Participant 3)

Working collaboratively provides students with opportunities to be more active, self-directed, responsible and innovative regarding their learning, which subsequently promotes academic performance, self-esteem and teamwork:[10]

'The peer learning model allows us to learn so much more than we would be exposed to in different clinical settings . having peers there allows them to bring in ideas from what they've learnt about different cases with individuals they've worked with and allows you to learn from their cases.' (Participant 1)

'It provides us with the opportunity to learn so much more and to learn so much more deeply.' (Participant 1)

'It provides us with an opportunity in a peer learning model to communicate with our peers and discuss with them.' (Participant 3)

The peer learning model relies on opportunities for peers to explore, collect, analyse, evaluate, integrate and apply relevant information for the learning task through collaboration. If this does not occur, it can impede the knowledge acquisition process.[10] This section is summarised well by the following statement, which CEs should consider:

'I think your experience with this model will depend on the partner you get, . it is based on your partner's critical thinking skills, their research, their writing and just what they are thinking and what they're willing to share.' (Participant 1)

Theme 3: Clinical skills

Clinical skills refer to the ability to apply theoretical knowledge appropriately to a patient in a clinical setting.[11] Participants reflected that they were able to develop their clinical skills more effectively when learning collaboratively with a peer:

'My peer had a completely different case from me. This doubled my exposure, not only in terms of like, clinical work and actual therapy and assessment but also in clinical writing. It assisted me with improving my skill overall. It worked so well that we ended up using the model on our own in other clinical settings. You are going to be watching all of their sessions so you also see specific techniques that will work for that diagnosis, so if you ever have a case like that you would have a solid understanding of what to do.' (Participant 3)

Some participants in both the post-practical questionnaires and the focus group reflected that they tended to focus on the clinical skills required for the case, as they can learn from the clinical skills and ideas that their peers imply and are able to discuss treatment ideas:

'It [peer learning model] provides an opportunity for equal partners to communicate about something rather than it being someone in a position of authority.' (Participant 1)

'Having peers there allows them to bring in ideas from what they have learned about different cases with individuals that they've worked with and allows you to see what their cases have been about and how they've been running their cases.' (Participant 2)

'With peer learning, there is another peer who you can kind of bounce your ideas off and they will understand what you're thinking and say whether they think it will work or not ... you can troubleshoot together.' (Participant 6)

Clinical writing skills was a subtheme that participants felt was developed through the use of this model. These skills developed owing to reading and engaging with assessment reports and weekly sessions with their peers:

'You see your partner's report, you see all of their sessionals and that develops your clinical writing skills.' (Participant 3)

'You are learning as you are reading through someone else's sessionals and this impacts your own clinical and writing skills.' (Participant 1)

Self-reflection emerged as a subtheme of clinical skills and refers to the ability of being able to critically evaluate an interaction with a client and analyse the strengths and weaknesses of that interaction.[12] Participants stated that in the traditional model they often are provided with vague, general feedback regarding their clinical skills, which in turn does not support the development of their own clinical or self-reflection skills:

'Feedback that your supervisor will say to you, as you know, good, well done, you ran your session nicely today or I think you should change the session. It's very limited surface level feedback that you get given.' (Participant 2)

In the peer learning model, participants were able to develop reflective skills, as they were required to think more critically about the feedback that they provided to their peers to ensure that the latter were able to learn and develop. This feedback is crucial, as reflective skills are essential to enhance knowledge, skills and humanity within the profession.[13] These skills are also outcomes for the practical placements and are supported by this model:

'I found it quite difficult to actually provide good critical feedback because I struggle with this myself ... I felt like I was not benefiting my partner in the feedback I was giving and I knew I must improve it.' (Participant 3)

'Giving feedback to my peers also improved my skills at a certain level because I also didn't want to give generic feedback. So, I would be more aware of what worked, what didn't work, and aware of the finer details that I might not always notice and then I was able to apply that in my own therapy sessions.' (Participant 2)

Theme 4: Professionalism

Professionalism is a socially constructed concept that defines the behaviours that occur between a clinician and patient or between clinicians.[14] Essential aspects of professionalism include: (i) knowledge, skills and performance; (ii) safety and quality; (iii) communication and teamwork; and (iv) maintaining trust.[15] Communication has been noted as an essential component of professionalism in the clinician-patient dyad and between clinicians.[12] Bulk et al.[12] noted that students are exposed to professionalism in an academic setting, but it is often challenging to teach students the skills in a clinical setting. Commonly used methods for teaching professionalism include lectures, case scenarios, reflective practice and role modelling.[15] The subtheme of communication with other professionals was demonstrated by the comments from all of the participants in the questionnaires and the focus group:

'It provides us with a huge opportunity to learn to work with other people ... it is an opportunity to learn how to communicate and engage with someone on an idea and bringing your own perspective.' (Participant 1)

'It has allowed us to critically analyze our skills also at a professional level . we were told at one site that our supervisor needs to be treated as a professional colleague, so we were not supposed to use her as a supervisor . and I think peer learning model helped me to do that because it's allowed me to see how to bring my perspective in whilst taking someone else's perspective in - put both of our skills together in order to work towards the benefit of the client.' (Participant 2)

'So I think there has to be a sense of professionalism, this is my peer but it still has to be a professional situation where I want to better my peer's skills as well as mine at the same time.' (Participant 4)

Students were able to learn how to behave in a professional manner with colleagues in a clinical setting. This model therefore supports the development of professionalism through clinical experience. As observed in themes 2 and 3, there was also the development of skills and knowledge. The peer learning model may therefore also ensure that other aspects of professionalism are developed through the model, which need to be explored in future research.

Conclusion

Overall, this peer learning model has proven to be successful in this pilot study to combat both the practical and pedagogical challenges that are currently experienced in the SLP programme in SA. This model improved student professional, clinical, theoretical, writing and self-reflection skills compared with the traditional model. The findings in terms of the improved skills support those found by both the physiotherapy and nursing faculties.

Future studies need to include how this model would work in different settings such as hospitals. It would also be important to determine how this model might work in a different patient population and in different years of study. The impact of power dynamics on teaching and learning on practical placements for SLP students in the SA context requires further exploration. Novel findings of this study include the exploration of how a peer learning model changed the power dynamics seen in a typical teaching scenario and how this shift can impact on learning and integration of skills.

Study limitations

There were limitations to this study, as it was conducted in one cohort of students only. However, as this was a pilot study, the cohort size was acceptable and could be used in future studies. A longitudinal design could also be used to look at the growth of students in different areas and at different levels of study.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We thank the students who made it possible for us to perform this study.

Author contributions. KC provided a substantial contribution to conceptualisation, design, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. NB provided a substantial contribution to data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding. Funding was provided by the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Pillay M, Tiwari R, Kathard H, Chikte U. Sustainable workforce: South African audiologists and speech therapists. Hum Resour Health 2020;18(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00488-6 [ Links ]

2. Freire P. Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. [ Links ]

3. Sevenhuysen S, Nickson W, Farlie M, Raitman L, Keating J. The development of a peer assisted learning model for the clinical education of physiotherapy students. J Peer Learn 2013;6(1):30-45. [ Links ]

4. Pálsson Y, Mártensson G, Swenne CL, Ädel E, Engström M. A peer learning intervention for nursing students in clinical practice education: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today 2017;51:81-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.01.011 [ Links ]

5. King C, Edlington T, Williams B. The 'ideal' clinical supervision environment in nursing and allied health. J Multidiscip Healthc 2020;13:187-196. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S239559 [ Links ]

6. Snowdon DA, Sargent M, Williams CM, Maloney S, Caspers K, Taylor NF. Effective clinical supervision of allied health professionals: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;20(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4873-8 [ Links ]

7. Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res 2021;21(1):37-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360 [ Links ]

8. De Stefano J, Hutman H, Gazzola N. Putting on the face: A qualitative study of power dynamics in clinical supervision. Clin Superv 2017;36(2):223-240. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2017.1295893 [ Links ]

9. Philp K, Guy G, Lowe R. Social constructionist supervision or supervision as social construction? Some dilemmas. J Syst Ther 2007;26(1):51-62. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2007.26.L51 [ Links ]

10. Williamson SN, Becejac LP. The impact of peer learning within a group of international post-graduate students -a pilot study. Athens J Educ 2018;5(1):7-27. https://doi.org/10.30958/aje.5-1-1 [ Links ]

11. Mok CKF, Whitehill TL, Dodd BJ. Problem-based learning, critical thinking and concept mapping in speech-language pathology education: A review. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2008;10(6):438-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754950080227749 [ Links ]

12. Bulk LY, Drynan D, Murphy S, et al. Patient perspectives: Four pillars of professionalism. Patient Exp J 2019;6(3):74-81. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1386 [ Links ]

13. Pretorius L, Ford A. Reflection for learning: Teaching reflective practice at the beginning of university study. Int J Teach Learn Higher Educ 2016;28(2):241-253. [ Links ]

14. Van de Camp K, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Grol RPTM, Bottema BJAM. How to conceptualise professionalism: A qualitative study. Med Teach 2004;26(8):696-702. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590400019518 [ Links ]

15. Morihara SK, Jackson DS, Chun MBJ. Making the professionalism curriculum for undergraduate medical education more relevant. Med Teach 2013;35(11):908-914. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.82027 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

K Coutts

kim.coutts@wits.ac.za

Accepted 7 November 2022