Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.15 n.2 Pretoria Jun. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2023.v15i2.1690

RESEARCH

The approach to undergraduate research projects at Namibia's first School of Medicine

M A KandingoI; H ZaireII; Q WesselsIII; L N N ShipinganaIV; O K H KataliIV

IMB ChB; Human, Biological and Translational Medical Sciences, Hage Geingob Campus, School of Medicine, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

IIMSc, BSc; Human, Biological and Translational Medical Sciences, Hage Geingob Campus, School of Medicine, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

IIIPhD (Anatomy), PhD (HSE), FHEA; Human, Biological and Translational Medical Sciences, Hage Geingob Campus, School of Medicine, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

IVMSc, BSc Hons; Human, Biological and Translational Medical Sciences, Hage Geingob Campus, School of Medicine, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The integration of undergraduate research (UR) in biomedical curricula has gained much interest

OBJECTIVE: To investigate the research focus of compulsory UR in the medical curriculum of the University of Namibia's School of Medicine

METHODS: A retrospective mixed-methods document review was performed on 42 research projects using the 5C framework that assessed students' ability to Cite, Compare, Contrast, Critique and Connect in their research reports

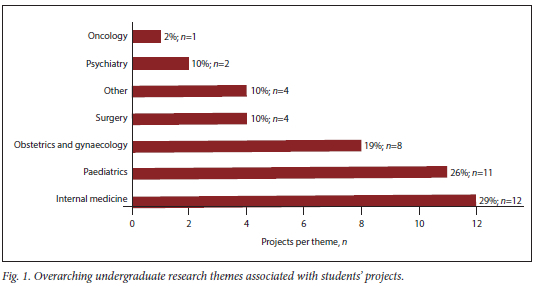

RESULTS: Students' research projects focused on internal medicine (29%; n=12), paediatrics (26%; n=11), obstetrics and gynaecology (19%; n=8), surgery (10%; n=4), psychiatry (5%; n=2) and oncology (2%; n=1). A final category is other, which included health professions education and anatomy (10%; n=4). Students' reports had aims, objectives or goals that were correctly done. Students' review of the literature reflected their ability to cite relevant scholarly works and to compare these by highlighting agreements or disagreements. Contrasting and critiquing research findings proved to be challenging

CONCLUSION: Findings from the current study indicate variability in the degree of students' research competence. It appears that the elements of critical thinking and appraisal require further strengthening within the existing curriculum

Student participation in undergraduate research (UR) has gained much ground in recent years.[1] Active participation in UR has the potential to develop critical thinking, engage students in inquiry-based learning, and facilitate the formation of linkages between research and teaching.[1-3] The importance and value of UR have been recorded extensively and include the development of skills and interest in research,[4] the fostering of advancement of clinician-scientists[5] and the acquisition of transferable skills such as communication and teamwork.[6,7] Most UR programmes involve teaching research methods that help students to develop research-related inquiry skills, participate in research discussions, learn about current research within a specific discipline, assist with data collection and undertake research, and learn about problem solving.[8]

The facilitation of UR programmes has many challenges. Knight et al[6] reported that finding enough skilled supervisors is particularly challenging. Furthermore, the supervision of research projects must compete with a full academic curriculum and deadlines associated with each phase of the project.'61 The ability of inquiry-based learning activities such as UR to stimulate interest among students rests upon various factors. Students should be afforded opportunities to explore what they want to learn, as well as the questions they have regarding a subject-specific research project.[8] Experience has shown that students tend to encounter difficulties in writing research proposals, as they do not fully comprehend what constitutes a good research proposal.'91 The ability to translate students' research projects into a presentation at a scientific meeting or a publication in a peer-reviewed academic journal is another challenge.[10] One possible reason for these challenges points towards the perceptions of academic staff who view students' projects as being of poor quality and thus unpublishable.[6]

Despite the potential barriers, UR remains relevant.[1] It is important to note that quality and impactful scientific research aimed at addressing the disease burden requires the emergence of physician-scientists.[11] Early introduction of UR in medical curricula has the potential to foster physician-scientists.[1,11] Practice-based learning that relies on the interaction between theoretical concepts and experience gained through active research was proposed by De Vegt et al.[1] in 2021. Practical experience through active engagement in UR is believed to help students form a closer connection between research and theory.[1]

In this article, we report on the nature of medical students' research reports at the University of Namibia (UNAM)'s School of Medicine (SoM). We address the evaluation of one of the sixth-year cohorts and the research reports associated with the MB ChB degree programme.

Setting

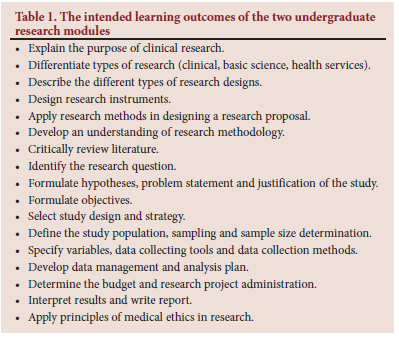

Initially, at UNAM, UR modules were presented as Independent Research Studies (IRS), Research Methods and Project for the MB ChB and BPharm degree programmes, respectively.[12] The modules were developed to instil the underlying skills critical to research (the intended learning outcomes for both modules are presented in Table 1).[12] Currently, the modules continue to form a compulsory element of the curricula, notwithstanding changes in the names of these modules and the extension of the MB ChB programme to include a sixth academic year (formerly offered over 5 years[12]). The UR commences with a Research Methods and Proposal Writing module (8 credits and 160 notional hours) and ends with the Research Project module (8 credits and 320 notional hours), which is facilitated in a blended format across different schools within the faculty. As for the MB ChB programme, the first module is offered afresh to each cohort during their third academic year. Therefore, all MB ChB students are expected to progress from the conceptualisation of a research project through writing a proposal in their third academic year. This approach is facilitated through a blended learning format and is aimed at fostering research-related skills. Consequently, the topics of UR at UNAM are proposed by each student and/or their supervisor. Members of the school serve as supervisors and guide students toward streamlining their projects. All academic members are required to supervise student projects and the overall aim is to serve as mentors throughout students' research journey.

Once the Research Methods and Proposal Writing module is completed, students progress by obtaining ethical approval from the Namibian Ministry of Health and Social Services through the school's research committee. Ethical approval is obtained during the fourth-fifth academic year, where self-directed learning and supervisor engagement are exercised intensively. The fifth and sixth academic years are devoted to data collection and writing of a research report, which accounts for the Research Project module.

Materials and methods

A retrospective mixed-methods approach was followed, which entailed a qualitative document review (QDR) with the presentation of dichotomous data in quantitative form. The study was conducted by one of our undergraduate MB ChB students (MAK) and co-authors in 2021 to assess the research focus of UR projects. The study was done at UNAM's SoM and data were obtained from the MB ChB research reports of the 2017 cohort. A total of 45 research reports were reviewed and 42 were finally subjected to QDR. Three reports were excluded, as they were either proposals or from repeating students, and without ethical approval, as opposed to completed projects. The thematic focus, based on a clinical specialty or related to biomedical science, was documented. The research reports were assessed for alignment of the aim and goals of each project and whether these were achieved by the methods used and the findings that were presented. This procedure was assessed through the identification of alignment between the aim, objective and goals and the presentation of the research findings. The assessment of the 42 research reports led to the production of categorical data for the study, where the research components were evaluated as variables. The research reports were evaluated by determining if the specific component was included or not, and if it was correctly done by producing dichotomous data with yes (1) or no (0) scores, respectively. Descriptive statistics were carried out to produce frequencies of the research components included in the reports.

Finally, document analysis entailed a conceptual approach, whereby important components of students' research reports were assessed. The criteria for QDR were adapted from the 5C approach (Cite, Compare, Contrast, Critique and Connect) to writing a literature review.[13] Even though Sudheesh et al.[13] used the 5C approach to appraise a literature review, the current study employed the same framework to appraise the research reports. For the purpose of our study, we wanted to establish whether the research report:

• kept to its primary focus by citing relevant scholarly works (Cite or C1)

• compared the literature by highlighting what the literature agrees on (C2A) and whether similar approaches (C2B) were used to analyse the research phenomenon (Compare or C2)

• referred to contrasting done in reference to the current body of knowledge (Contrast or C3)

• critiqued the literature in reference to the findings (Critique or C4);

• made connections (C5A) with the current body of knowledge and synthesise (C5B) new information in writing the discussion (Connect or C5).

Results

A total of 45 research reports and proposals were supervised by 25 staff members. Forty-two students' research reports met the criteria for QDR (Supplementary material A: https://www.samedical.org/file/2010). Three projects were excluded from the study, as they were proposals of repeating students that were not finalised, with no ethical approval. On average, each staff member supervised 2 student projects. Eight staff members supervised 2 student projects, and 3 supervised 3 projects at a time. However, 1 supervisor supervised 4 projects, while most (n=13) supervised only 1 project at a time.

Overarching research themes were identified based on the primary clinical specialties of internal medicine, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, psychiatry, surgery and oncology. Most projects focused on internal medicine (29%; n=12), followed by paediatrics (26%; n=11) and obstetrics and gynaecology (19%; n=8), while only 2 projects focused on psychiatry (5%) and 1 project on oncology (2%). Four projects (10%) focused on surgery and 4 more were categorised as other (10%). The latter included 3 health professions education themes and 1 anatomy-based study (Fig. 1). The titles of these research reports are presented in Supplementary material A (https://www.samedical.org/file/2010), while the frequencies of the different themes are shown in Fig. 1. These findings were considered as the research focus of each student.

The second aspect of the current study considered the approach of students' research reports. The reports were assessed to determine whether they included the aims, objectives and goals and if they were correctly done (achieved). The majority of the research reports included the relevant components that were assessed (Table 2). The overarching aim component was included in 98% (n=41) of the reports and 86% (n=36) included long-term goals (Supplementary material B: https://www.samedical.org/file/2010). Clear and well-structured objectives were observed in 74% (n=31), whereas the remainder of the reports (26%; n=11) only stated an overarching aim. Some research reports combined the objectives, aims and goals under the objectives heading, which reflects the researcher's inability to differentiate between these concepts. A total of 34 reports (81%) achieved their outlined objectives, goals and aims (Supplementary material B: https://www.samedical.org/file/2010).

Furthermore, the quality of the research reports was critically appraised using the 5C framework, which demonstrated varied results in the report consistency (Table 1). In writing the report's framework, most students (79%; n=33) could keep to the primary focus (C1) throughout. Students were able to find relevant literature and point out what is known, what is agreed on, make connections and then synthesise. It was observed that most (95%; n=40) of the reports included a comparison (agree: C2A) with the existing literature. In addition, 76% (n=32) of the reports aligned the cited literature with the research phenomenon under investigation with similar approaches (C2B), which were mostly international or local studies. Close to half (48%; n=20) of the reports had contrasting (C3) or different approaches to the research questions in terms of the population and methodology used. However, few reports (14%; n=6) critiqued (C4) the existing literature in terms of the limitations of the approach used, the reproducibility of the outcomes and the appropriateness or limitations of the methodology that was applied to the studies that they cited. The majority of students succeeded in making connections (C5A; 74%; n=31) between their literature review, study variables, methodology and results. However, slightly more than half (57%; n=24) of the students were able to synthesise new information (C5B) based on their results.

Discussion

The integration of UR in biomedical curricula has been found to be feasible, especially through a practice-based learning approach. [1] Research should be encouraged early on in students' medical career.[14] UR at UNAM's SoM forms a compulsory element for all MB ChB students, and staff members are required to serve as mentors and advisors over a period of 4 years. The final outcome for each student is a research report. Students' research efforts also provide opportunities for independent learning and development of research-related skills. We assessed the quality of students' research reports by using a 5C framework.[13]

Findings from this study indicate that most students selected topics that focused on internal medicine and elements of maternal and child health. This selection is of particular interest, as the disease burden in Namibia relates to communicable diseases (e.g. tuberculosis and HIV) and non-communicable diseases (especially diabetes and cardiovascular-related conditions).[15,16] Equally, students predominantly conduct their clinical rotations in the two referral state hospitals in Namibia, which treat many disease cases. They are therefore exposed to the heart of the current health burden.

Findings further indicate variability in the degree of students' research competence. The review of the literature was well executed and reflected students' ability to cite relevant scholarly works and draw comparisons (compare). The majority of the reports had aims, objectives or goals that were correctly done. However, students' ability to contrast their research findings with those of previous work proved to be challenging. The same holds true for students' ability to critique current literature related to their study and connecting their findings with those of previous work. It appears that these elements of critical thinking and appraisal require further strengthening within the existing curriculum. Critical appraisal is one of the primary research-related attributes that relies on critical evaluation of data and the subsequent synthesis of new information.[5]

Barriers to critical thinking, as discussed by Mangena and Chabeli,[17] include lack of faculty knowledge, poor educational backgrounds, inappropriate student selection criteria, insufficient facilitation of critical thinking in medical education, resistance to change by faculty members and inappropriate assessment activities. Again, these barriers were not assessed within the context of the current study, but they all have merit. One of the major contributions to these barriers is the student-supervisor challenge, which relates to the distribution of students per supervisor. We found that the quality of research supervision might be impeded by the large number of student projects per supervisor. This situation in turn could impact the quality of students' projects. Solutions to mitigate this phenomenon are therefore warranted. A possible solution might be to form research teams, where a larger project is broken down and pursued by a small cohort of students. The larger project could therefore be subdivided into specific research questions and objectives, permitting one supervisor to facilitate multiple projects.

Compulsory research in undergraduate medical curricula, as presented here, has the advantage of fostering clinician-scientists.[5,11] However, this comes at a price. Some of the major challenges, which were not explored in this article, relate to the allocation of supervisors, supervisors' competence in the study area and finding novel and worthwhile project ideas. These issues, as well as other challenges and barriers associated with UR, are well documented.[5,11,18,19]

Finally, the overall impact of UR projects requires further investigation and should be assessed by considering their value in relation to the existing body of knowledge, influence on practice and ability to augment or transform existing policies. The current study did not assess whether students' data analyses were appropriately aligned with the methodology used, and further research is required to fully assess the overall quality of the projects. Conclusion

In this study we aimed to appraise the nature of UR of medical students using a transferrable 5C approach framework. Findings indicate that students displayed a general understanding of research writing and methodology. The majority of undergraduate MB ChB students appear to have a clear understanding of the aims, goals and objectives and how to achieve them through the research project. However, critical thinking proved to be a major challenge. The study emphasises the value of the framework that was used to gauge the nature of UR and subsequently rectify possible gaps and limitations regarding the inclusion of UR in curricula. The authors also believe that the current study provides some insights and important considerations that permit the reader to incorporate UR in their curricula.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors wish to acknowledge students and supervisors, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Author contributions. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The qualitative document analysis was done by MAK. Data analyses were performed by HZ and LNNS, and OKHK worked on the background and setting sections. The first draft of the manuscript was written by QW and reviewed by HZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. De Vegt F, Otten JDM, de Bruijn DRH, et al. Research in action E students' perspectives on the integration of research activities in undergraduate biomedical curricula. Med Sci Educ 2021;31:371-374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01228-8 [ Links ]

2. Elsen GMF, Visser-Wijnveen GJ, van der Rijst RM, van Driel JH. How to strengthen the connection between research and teaching in undergraduate university education. High Educ Quart 2009;63(1):64-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00411.x [ Links ]

3. Spronken-Smith R, Walker R. Can inquiry-based learning strengthen the links between teaching and disciplinary research? Stud High Educ 2010;35(6):723-740. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903315502 [ Links ]

4. Chang Y, Ramnanan CJ. A review of literature on medical students and scholarly research: Experiences, attitudes, and outcomes. Acad Med 2015;90(8):1162-1173. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000702 [ Links ]

5. Laidlaw A, Aiton J, Struthers J, Guild S. Developing research skills in medical students: AMEE Guide No. 69. Med Teach 2012;34(9):754-771. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.704438 [ Links ]

6. Knight SE, van Wyk JM, Mahomed S. Teaching research: A programme to develop research capacity in undergraduate medical students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0567-7 [ Links ]

7. Linn MC, Palmer E, Baranger A, Gerard E, Stone E. Undergraduate research experiences: Impacts and opportunities. Science 2015;347(6222):1261757. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261757 [ Links ]

8. Brew A. Understanding the scope of undergraduate research: A framework for curricular and pedagogical decision-making. High Educ 2013;66(5):603-618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9624-x [ Links ]

9. Abdulai RT, Owusu-Ansah A. Essential ingredients of a good research proposal for undergraduate and postgraduate students in the social sciences. Sage Open 2014;4(3):21582440145. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2158244014548178 [ Links ]

10. Nel D, Burman RJ, Hoffman R, Randera-Rees S. The attitudes of medical students to research. S Afr Med J 2014;104(1):33-36. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.7058 [ Links ]

11. Ommering BWC, van Blankenstein FM, Waaijer CJF, Dekker FW. Future physician-scientists: Could we catch them young? Factors influencing intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for research among first-year medical students. Perspect Med Educ 2018;7(4):248-255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0440-y [ Links ]

12. Jacobson C, Hunter CJ, Wessels Q. Biomedical research at Namibia's first school of medicine and pharmacy. Med Sci Educ 2013;23:135-140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03341818 [ Links ]

13. Sudheesh K, Duggappa DR, Nethra SS. How to write a research proposal? Indian J Anaesth 2016;60:631-634. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0019-5049.190617 [ Links ]

14. Murdoch-Eaton D, Drewery S, Elton S, et al. What do medical students understand by research and research skills? Identifying research opportunities within undergraduate projects. Med Teach 2010;32(3):e152-e160. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421591003657493 [ Links ]

15. Kibuule D, Aiases P, Ruswa N, et al. Predictors of loss to follow-up of tuberculosis cases under the DOTS programme in Namibia. ERJ Open Res 2020;6(1). https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00030-2019 [ Links ]

16. GBD 2019 Universal Health Coverage Collaborators. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990 - 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020;396(10258):1250-1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30750-9 [ Links ]

17. Mangena A, Chabeli MM. Strategies to overcome obstacles in the facilitation of critical thinking in nursing education. Nurs Educ Today 2005;25(4):291-298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2005.01.012 [ Links ]

18. Russell CD, Lawson McLean A, MacGregor KE, Millar FR, Young AM, Funston M. Perceived barriers to research in undergraduate medicine. Med Teach 2012;34(9):777-778. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.700143 [ Links ]

19. Alsaleem SA, Alkhairi MAY, Alzahrani, MAA, et al. Challenges and barriers toward medical research among medical and dental students at King Khalid University, Abha, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health 2021;9:706778. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.706778 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Q Wessels

qwessels@unam.na

Accepted 22 January 2023