Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.15 no.1 Pretoria Mar. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2023.v15i1.1602

RESEARCH

Developing indicators for monitoring and evaluating the primary healthcare approach in health sciences education at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, using a Delphi technique

M I DatayI; S SinghII; J IrlamI; F WaltersII; M NamaneIII

IMB ChB, DPhil, FCP (SA), MMed (Int Med); BSc, BSc (Med) Hons, MSc, MPhil; Primary Health Care Directorate, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIBSpHT, MA, PhD; BSpHT, MSc; Division of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIIMB ChB, MPhil (Fam Med), MSc, MSc Med Sci, FCFP (SA); Division of Family Medicine, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. The Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS), University of Cape Town (UCT) adopted the primary healthcare (PHC) approach as its lead theme for teaching, research and clinical service in 1994. A PHC working group was set up in 2017 to build consensus on indicators to monitor and evaluate the PHC approach in health sciences education in the FHS, UCT.

OBJECTIVE. To develop a set of indicators through a Delphi technique for monitoring and evaluating the PHC approach in health sciences curricula in the FHS, UCT.

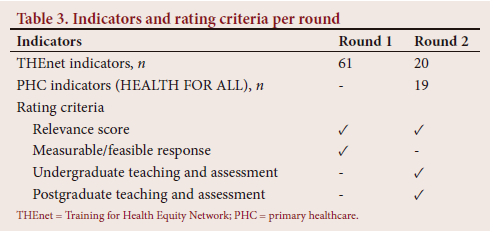

METHODS. A national multidisciplinary Delphi panel was presented with 61 indicators of social accountability from the international Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) for scoring in round 1. Nineteen PHC indicators, derived from a mnemonic used in the FHS, UCT for teaching core PHC principles, were added in round 2 to the 20 highest ranked THEnet indicators from round 1, on recommendation of the panel. Scoring criteria used were relevance (in both rounds), feasibility/measurability (round 1 only) and application of the PHC indicators to undergraduate and postgraduate teaching and assessment (round 2 only).

RESULTS. Of the 39 indicators presented in the second round, 11 had an overall relevance score >85% based on the responses of 16 of 20 panellists (80% response rate). These 11 indicators have been grouped by learner needs (safety of learners - 88%, teaching is appropriate to learners' needs and context - 86%); healthcare user needs (continuity of care - 94%, holistic understanding of healthcare - 88%, respecting human rights - 88%, providing accessible care to all - 88%, providing care that is acceptable to users and their families - 87%, providing evidence-based care - 87%); and community needs (promoting health through health education - 88%, education programme reflects communities' needs - 86%, teaching embodies social accountability - 86%).

CONCLUSION. The selected indicators reflect priorities relevant to the FHS, UCT and are measurable and applicable to undergraduate and postgraduate curricula. They provided the basis for a case study of teaching the PHC approach to our undergraduate students.

The Declaration of Alma-Ata on primary healthcare (PHC), adopted in 1978 at the landmark conference hosted by the World Health Organization (WHO), recognised the need for equity-driven healthcare and aspired towards the goal of 'health for all by the year 2000'.[1] The PHC approach was reaffirmed at a number of subsequent conferences, including the 2008 WHO PHC conference held in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso,[2] and the Astana Declaration of 2018.[3] In South Africa (SA), PHC was adopted as the cornerstone of the healthcare system, with a firm plan to re-engineer healthcare and to address issues around inequity, inadequate access and a grossly divided healthcare system.[4]

The concept of social accountability has been widely adopted within international health sciences education over the past decade to direct institutions to produce graduates who can effectively respond to priority health needs, in partnership with the health sector and the communities they serve.[5] A key set of indicators has been developed by the international Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) to assist health sciences faculties to align training with community needs.[6]

In 1994, the Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS), University of Cape Town (UCT) adopted the PHC approach as its lead theme in teaching, research, health services and community engagement, and in 2003 established the interdisciplinary PHC directorate to champion the PHC approach. It is important that there be an evaluation of health sciences curricula to determine whether they adequately prepare health sciences graduates to function in a health system underpinned by the PHC approach. A PHC working group was established in 2017 to develop indicators for monitoring and evaluating the PHC approach in the FHS, and to undertake a case study of PHC teaching of final-year students.[7]

The objective of this phase of the study was to develop a set of indicators through a modified Delphi technique[8-10] for monitoring and evaluation of the PHC approach in health sciences curricula in the FHS, UCT. A companion paper has described the case study that reviewed course documents and interviewed educators and students at selected community-based education sites of the FHS.[7]

Methods

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, FHS, UCT (ref. no. 157/2018) prior to commencement of the study.

Participants

Eligible participants for the Delphi panel were educators and practitioners in PHC, known to the research team as having expertise in this field. There were no exclusion criteria. The expert group was expected to be relatively homogeneous. Sample size of Delphi studies can vary from 15 to 20, but some can have >50 participants.[11] Expecting a response rate of ~50 - 70%, 28 experts were identified in round 1 of the Delphi, and recruited via email by the authors and their colleagues. Informed consent was obtained from each Delphi panellist. Participants invited represented 10 different professions, including basic sciences, family medicine, internal medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, paediatrics, physiotherapy, public health, speech language pathology and surgery. Participants were from different provinces in SA, with the majority (n=21; 75%) based at one of the three universities in the Western Cape Province and the rest from other national universities and government research institutions.

Indicators

A search for published indicators was conducted on PubMed, EBSCOhost and Google Scholar, using the terms:

Primary Health Care [Mesh] OR Primary Health Care OR Alma Ata

AND

Quality Indicators, Health Care [Mesh] OR Indicators

AND

Education, Medical [Mesh] OR health sciences education OR medical education OR clinical education

No framework was found that specifically included PHC indicators for health sciences curricula. There was only a set of indicators that applied to a service delivery context.[12] The Framework for Socially Accountable Health Workforce Education of THEnet was the only suitable framework known to the group.[6] The framework consists of 179 indicators divided into the categories: 'What needs are we addressing?' 'How do we work?' 'What do we do?' 'What difference do we make?' The working group reviewed the entire framework and decided to select indicators only from the category 'What do we do?', which were perceived to be most relevant to the required purpose within the FHS. Sixty-one of 74 indicators in the 'What do we do?' category were short-listed by the group, and some were reworded for clarity and applicability in the FHS, UCT context.

Round 1

The 61 indicators were listed in an Excel 365 (Microsoft Corp., USA) spreadsheet. Each indicator had a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree = 5; agree of PHC in education and training) and three response options (yes = 3; maybe = 2; no = 1) to signal whether an indicator was measurable or feasible. There was provision for comments and suggestions for additional or alternative indicators by the participants. Members of the Delphi panel were emailed the spreadsheet with instructions for completion within 2 weeks, and a reminder was sent before the due date.

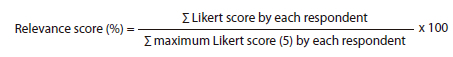

Eighteen of 28 members (64%) responded (family medicine, n=6; internal medicine, n=1; nursing, n=2; paediatrics, n=1; physiotherapy, n=1; public health, n=4; speech language pathology, n=2; and surgery, n=1). Each indicator was scored for relevance using the formula:

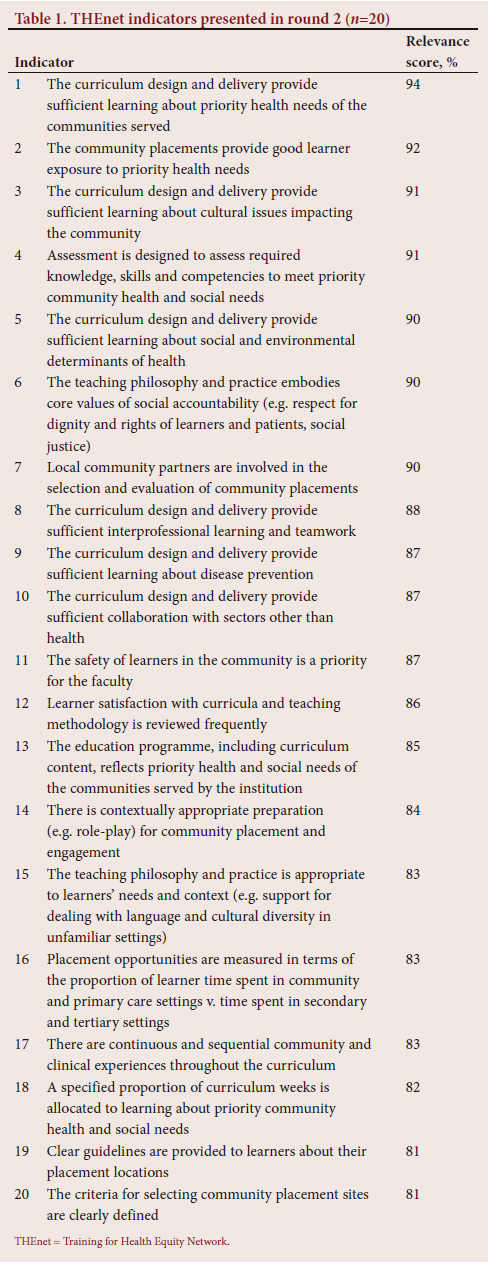

The 20 THEnet indicators with the highest relevance scores were included in the revised questionnaire for round 2 (Table 1).

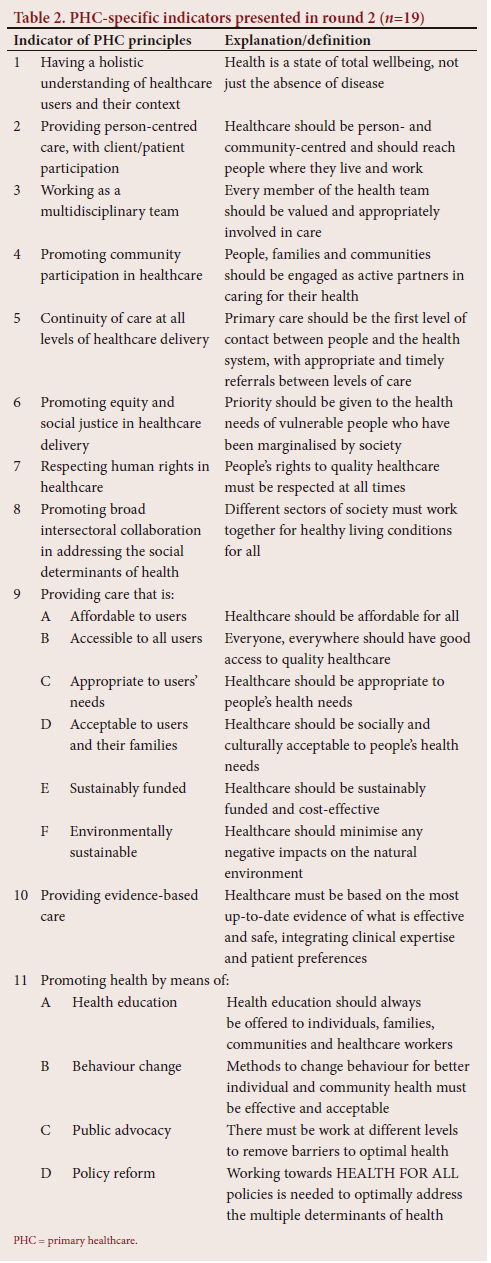

The exclusive use of THEnet indicators as a measure of PHC implementation in health sciences education at the FHS, UCT was questioned by an experienced panellist. It was pointed out that the task of the research group was to evaluate the implementation of PHC principles in the curriculum, and that the indicators presented to the panel related exclusively to social accountability, which could not be conflated with PHC. The research team agreed and added 19 indicators in round 2 that were derived from the HEALTH FOR ALL mnemonic (H = health; E = equity/ equality; A = accessibility; L = listening to/learning from the community; T = teamwork; H = health promotion; F = funding; O = other sectors; R = rights and responsibilities; A = acceptability and appropriateness; L = levels of care; L = literature (evidence based)), which is regularly used in the FHS to teach the principles of the PHC approach (Table 2).[7]

Some round 1 panellists questioned the validity of the category 'measurable/feasible', and after agreement that this was not easy to assess, it was removed in round 2. Criteria were added in round 2 for whether the 19 PHC-specific indicators should be 'taught and assessed', 'taught only' or 'neither taught nor assessed' to undergraduates and/or postgraduates (Table 3).

Round 2

The round 2 questionnaire asked panellists to rate the relevance of all 39 indicators using the same 5-point Likert scale as in round 1. Sixteen of the 20 members (80%) responded. Responses from round 2 were again scored and ranked by relevance. A total of 21 THEnet and PHC indicators scored >80% in the second round, but it was decided to raise the cut-off for inclusion in the final set to 85% to limit the indicators to a number deemed feasible for the subsequent phases of the research. A third round was part of the original protocol; however, it was decided that no further rounds needed to be conducted, as there were sufficient responses for consensus, and insufficient time without delaying the case study phase.

Results

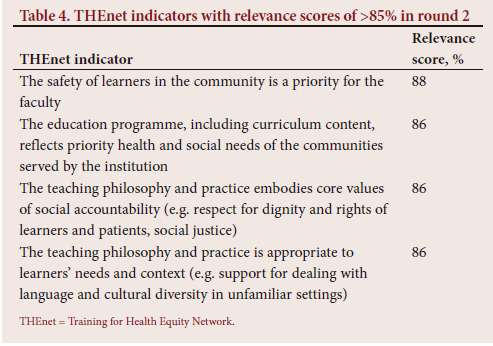

Four of THEnet indicators had a relevance score of >85%. These indicators measure priority given to student safety in communities (88%), reflection of priority health and social needs of communities in the education programme (86%), embodiment of social accountability in teaching philosophy and practice (86%) and whether the teaching philosophy and practice is appropriate to learners' needs and context (86%) (Table 4).

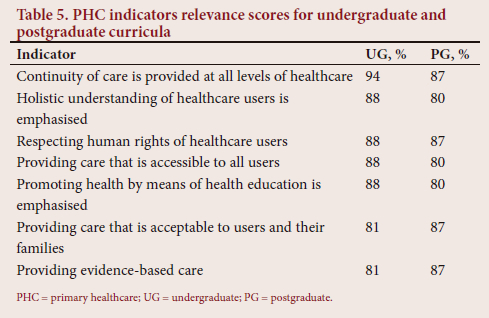

There were 5 PHC indicators for undergraduates and 4 for postgraduates that had relevance scores of >85%. Common indicators across undergraduate and postgraduate study were continuity of care and respecting human rights of healthcare users (Table 5). The majority of the panel thought that the PHC indicators should be both taught and assessed in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula. The 5 undergraduate PHC indicators were used with the abovementioned 4 THEnet indicators in the case study phase of the research, which has been previously published.'7-

Discussion

A conventional Delphi technique was used to harness the expertise of practitioners from a diversity of health professions in prioritising indicators for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the PHC approach in FHS, UCT curricula. Their feedback from round 1 led to the addition of PHC-specific indicators to THEnet indicators in round 2. After two rounds, 4 THEnet indicators and 7 PHC-specific indicators emerged as the most relevant.

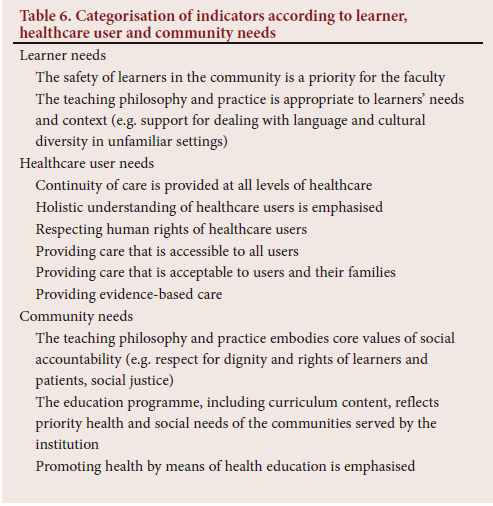

We have grouped these indicators into the following categories: learner needs, healthcare users' needs and community needs (Table 6). When grouping the indicators in this manner, it emerged that indicators prioritising learner needs related strongly to the social accountability framework, healthcare user indicators related strongly to the PHC approach and indicators prioritising community needs reflected both PHC and social accountability.

Learner needs

The emergence of 'safety of learners in the community is a priority' as the highest ranked THEnet indicator reflects prevalent concerns about personal safety in SA, which obliges health sciences curricula to engage meaningfully with communities around community entry, community values and partnerships for student work.[13] Determinants of community safety are multifactorial and thus also require intersectoral collaboration to address.[14] The safety of learners needs to be ensured not only in communities, but also within the broader understanding of the curriculum. Mental health has emerged as a major challenge at university institutions, with self-harm, bullying and hierarchical institutional cultures contributing greatly towards student distress.[15] These points tie in with the indicator 'The teaching philosophy and practice needs to be appropriate to learners' needs and context'. The curriculum needs to prepare students to engage not only with diverse societies, but also with the many life challenges they are likely to encounter. In addition to the professional work that students are expected to master during their careers, other multifaceted challenges (such as stress and limited resources) impact their lives. There is also a hidden curriculum that needs to be addressed when working for social accountability.[16] It is therefore pertinent that the teaching philosophy encompasses a caring space where coping skills and resilience are prioritised.[15]

Healthcare user needs

Indicators of the needs of healthcare users were derived exclusively from the PHC principles and included continuity of care; providing evidence-based, acceptable, holistic and accessible care; and respecting human rights.

SA has a fragmented health system, which negatively impacts on continuity of care, patient experiences and health outcomes.[17,18] Health sciences curricula should therefore prepare graduates to address challenges within the health care system and to improve continuity of care.

Provision of holistic care is a key principle,[19] which differentiates the PHC approach from the biomedical approach that characterises much of clinical practice.[20] Holistic care recognises psychological and social impacts on health and patient management. When a curriculum prioritises holistic care, students can rather adopt a person-centred approach to address the psychosocial determinants of health.[21]

Human rights violations continue to perpetuate negative health outcomes, resulting in limited access to care due to physical, linguistic, disability and financial challenges, and ultimately poorer quality of care.[22] Educating health sciences students about human rights will conscientise them to recognise, and potentially redress, such violations.

A curriculum that prepares graduates for work in a multicultural society should equip them to provide care that is socially and culturally acceptable to healthcare users and their families. Students should therefore be made aware of, and respect, different healthcare needs, health-seeking behaviours and treatment choices. In preparing students for lifelong learning about safe and quality practice, it is essential that curricula develop their skills to critically appraise the research literature, and to provide evidence-based care that carefully considers their patients' preferences.

Community needs

The high ranking of the indicator on curriculum content needing to reflect the priority health and social needs of the communities served by the institution, signals the importance of contextually relevant curricula. Historically, prioritisation of content in health sciences curricula has been based on developments in the Global North.[23,24] Built on colonial and postcolonial infrastructures, health services in developing countries were not necessarily geared to deal with the priority needs of the communities being served.[23] Ways in which this can be addressed include using epidemiological data on the burden of disease and disability, and by engaging with local communities about their priority health and social needs.

Another community needs indicator states that the teaching philosophy and practice needs to embody core values of social accountability, such as respect for the dignity and rights of learners and patients, and social justice. The challenges of ensuring the rights and dignity of learners and patients have been well described in the literature.[25] The power imbalance is even more challenging when it involves deeper issues such as racism, or perceptions thereof,[26] gender-based violence[27] and bullying.[28] Addressing these issues in the curriculum requires widespread awareness and multipronged approaches to enhance the rights of learners and patients, such as safe spaces for reporting, a culture of zero tolerance and policy review that enables the abovementioned issues to happen.[29]

'Promoting health by means of health education' emerged as a priority indicator. Health promotion speaks to a model of improving health and wellness, compared with curricula of traditional models focused on illness.[30] Empowering health sciences students on how to deliver effective health education can help individuals and communities to understand factors that promote good health, maintain a healthy lifestyle and encourage appropriate health-seeking behaviours. Health education forms a cornerstone of health promotion, ideally enabling collaboration between healthcare practitioners, students and the community to identify health needs and to promote the health of the community.[31] Indicators of public advocacy and policy reform, which are also essential components of health promotion, should also be included.

Study strength and limitations

The strength of this study is that it represents a novel approach of integrating PHC and social accountability indicators. The limitations are that we were unable to do a third round because of time constraints, although consensus after two rounds was deemed sufficient. There was a preponderance of family physicians in the panel, which was not unexpected given the centrality of social accountability and PHC principles in the discipline of family medicine.

Conclusion

The Delphi technique enabled a consensus to be reached by a panel of moderately diverse healthcare professionals on the prioritisation of 11 indicators of the PHC approach in health sciences curricula in the FHS, UCT. Four were derived from THEnet framework and 7 from the HEALTH FOR ALL mnemonic that is used in the FHS for teaching the principles of the PHC approach. Nine of these indicators that were selected as priorities for teaching and assessment in undergraduate curricula were used in a case study of teaching PHC at community-based education sites of UCT's FHS.[7]

The PHC approach is more important than ever in a nation and world of growing inequities, and faculties of health sciences have a crucial role to play in educating the next generation of health professionals to exercise their agency in implementing PHC. Indicators such as social accountability and PHC in health sciences education appear to fill an important gap in the literature.

Declaration. The research for this study was done in partial fulfilment of the requirements for MID's MMed (Int Med) degree at the University of Cape Town.

Acknowledgements. We would like to thank Nadia Hartman, Melanie Alperstein, Fatima le Roux and Steve Reid, who were also part of the working group and contributed at different stages of development. We also wish to thank the experts who participated in the Delphi panel.

Author contributions. All authors complied with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors' rules of authorship and were part of formulating and conceptualising the article. The initial draft was prepared by MID, and subsequent work on the manuscript included inputs from all authors.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6 - 12 September 1978. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/almaata-declaration-en.pdf?sfvrsn=7b3c2167 (accessed 29 November 2022). [ Links ]

2. International Conference on Primary Health Care and Health Systems opens in Ouagadougou, WHO, Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/news/international-conference-primary-health-care-and-health-systems-opens-ouagadougou (accessed 29 November 2022). [ Links ]

3. Wass V The Astana declaration 2018. Educ Prim Care 201839(6)321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2018.1545528 [ Links ]

4. Naledi T, Barron P, Schneider H. Primary health care in SA since 1994 and implications of the new vision for PHC re-engineering. S Afr Health Rev 2011;2011(1):17-28. [ Links ]

5. Boelen C, Dharamsi S, Gibbs T. The social accountability of medical schools and its indicators. Educ Health 2012;25(3):180-194. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.109785 [ Links ]

6. THEnet Framework. Training for Health Equity Network. 2018. https://thenetcommunity.org/what-do-we-do/ (accessed 25 November 2022). [ Links ]

7. Irlam J, Datay MI, Reid S, et al. How well do we teach the primary healthcare approach? A case study of health sciences course documents, educators and students at the University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2021;13(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2021.v13i1.1284 [ Links ]

8. Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and Nominal Group in medical education research. Med Teach 2017;39(1):14-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2017.1245856 [ Links ]

9. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67(4):401-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [ Links ]

10. Van Schalkwyk SC, Kiguli-Malwadde E, Budak JZ, Reid MJA, de Villiers MR. Identifying research priorities for health professions education research in sub-Saharan Africa using a modified Delphi method. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(1):443. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02367-z [ Links ]

11. Hsu C-C. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus - practical assessment, research and evaluation. Pract Assess Res Eval 2007;12(10):1-8. https://doi.org/10.5959/eimj.v8i3.421 [ Links ]

12. Simou E, Pliatsika P, Koutsogeorgou E, Roumeliotou A. Quality indicators for primary health care. J Public Health Manag Pract 2015;21(5):E8-E16. https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000000037 [ Links ]

13. Galvaan R, Peters L. Occupation-based Community Development: Confronting the Politics of Occupation. Occupational Therapies Without Borders. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2017:283-291. [ Links ]

14. World Health Organization. Coordinated, Intersectoral Action to Improve Public Health. Advancing the Right to Health: The Vital Role of Law. Geneva: WHO, 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252815 (accessed 29 November 2022). [ Links ]

15. Galvaan R, Crawford-Browne S, Gamieldien F, et al. Report on the faculty-based engagements with stakeholders: Understanding 'uMgowo' - Mental Health Working Group. 2019. http://www.publichealth.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/8/FHS %20MHWG%20Report%202019.pdf (accessed 29 November 2022). [ Links ]

16. Sons J, Gaede B. 'I know my place. The hidden curriculum of professional hierarchy in a South African undergraduate medical program: A qualitative study. Res Square 2021. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-745000/v1 [ Links ]

17. Dudley L, Mukinda F, Dyers R, Marais F, Sissolak D. Mind the gap! Risk factors for poor continuity of care of TB patients discharged from a hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2018;13(1):e0190258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190258 [ Links ]

18. Joyner K, Mash B. Quality of care for intimate partner violence in South African primary care: A qualitative study. Violence Victims 2014;29(4):652-669. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00005 [ Links ]

19. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care Now More Than Ever. Geneva: WHO, 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43949 (accessed 29 November 2022). [ Links ]

20. Murphy JW. Primary health care and narrative medicine. Permanente J 2015;19(4):90-94. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/14-206 [ Links ]

21. Primary Health Care Performance. High quality primary health care: Comprehensiveness. 2019. https://improvingphc.org/improvement-strategies/high-quality-primary-health-care (accessed 17 December 2021). [ Links ]

22. Chapman AR. The Social Determinants of Health, Health Equity, and Human Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010:17-30. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781316104576.007 [ Links ]

23. Pentecost M, Gerber B, Wainwright M, Cousins T. Critical orientations for humanising health sciences education in South Africa. Med Humanit 2018;44(4):221-229. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2018-011472 [ Links ]

24. Duffy TP. The Flexner report - 100 years later. Yale J Biol Med 2011;84(3):269-276. Jamieson DW, Thomas KW Power and conflict in the student-teacher relationship. J Applied Behav Sci 1974;10(3):321-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/002188637401000304 [ Links ]

25. Wong B, Elmorally R, Copsey-Blake M, Highwood E, Singarayer J. Is race still relevant? Student perceptions and experiences of racism in higher education. Cambridge J Educ 2021;51(3):359-375. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764x.2020.1831441 [ Links ]

26. Gordon SF, Collins A. "We face rape. We face all things': Understandings of gender-based violence amongst female students at a South African university. Afr Safety Promotion: J Injury Violence Prevent 2013;11(2):93-106. [ Links ]

27. Keashly L, Neuman JH. Faculty experiences with bullying in higher education. Admin Theory Praxis 2010;32(1):48-70. https://doi.org/10.2753/atp1084-1806320103 [ Links ]

28. Warton G, Moore G. Gender-based violence at higher education institutions in South Africa. Saferspaces. www.tinyurl.com/a3z43cmj (accessed 25 November 2022). [ Links ]

29. Sayek I, Turan S, Bati AH, Demirören M, Baykan Z. Social accountability: A national framework for Turkish medical schools. Med Teach 2021;43(2):223-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1841889 [ Links ]

30. Whitehead D. Health promotion and health education: Advancing the concepts. J Adv Nurs 2004;47(3):311-320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03095.x [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

MI Datay

ishaaq.datay@uct.ac.za

Accepted 25 July 2022