Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.14 no.4 Pretoria dic. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2022.v14i4.1546

RESEARCH

Men in the service of humanity: Sociocultural perceptions of the nursing profession in South Africa

S Shakwane

PhD ; Department of Health Studies, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. The classification of nursing as a female-gendered profession, along with patriarchally determined cultural gender roles, makes it difficult for men to select nursing as a career and to excel in their caring capacity as nurses.

OBJECTIVE. To gain in-depth insights into and an understanding of male nursing students' perceptions of the nursing profession.

METHODS. A generic qualitative approach, which was explorative, descriptive and contextual, was used to conduct the study. Sixteen male nursing students at two nursing education institutions in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, were purposively sampled to participate in the study. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and unstructured observation. Thereafter, thematic analysis was used to analyse the data.

RESULTS. Three main themes were developed from the interview data. The participants perceived nursing as the extension of women's work, with low social status - nursing is not considered to be a profession for men. During the provision of nursing care, feelings of discomfort and embarrassment were experienced. They feared misinterpretation of their care, especially when caring for the naked body when alone with a patient. They resorted to the use of cautious caring, where they do not provide physical care alone, but seek support, especially from female nurses.

CONCLUSION. Male nursing students require role models to support them in their academic journey towards becoming competent practitioners. A male-friendly environment should be created to enable them to provide quality nursing care to all patients. The society needs to be empowered in understanding that men choose the nursing profession to provide care, and that they are capable of caring for the sick.

Gender imbalances in nursing education remain.[1] The proportion of men in nursing has persistently remained low, despite relative progress being noted with regard to the proportion of women entering professions previously deemed the realm of men.[2] In South Africa (SA), according to the South African Nursing Council (SANC), 2019 statistics on the provincial distribution of nursing manpower showed that only 10.4% of practising nurses were male, while 8% were male nursing students.[3] Historically, nursing has been viewed as compatible with the natural care or nurturing that women give spontaneously. This view has led to care being seen as a feminine virtue, and a way in which many women act on their moral beliefs.[4] The development of modern nursing, following the efforts of Florence Nightingale, led to the feminisation of the profession and largely excluded men from nursing as a career.[2] It is also viewed as emotional labour and a vocation that requires dedication, which has led to the division of labour and the gendered nature of care.[5] Men who choose nursing as a career encounter negative stereotypes, gender discrimination and restricted employment.[4] Society generally views men as unsuitable caregivers, being incapable of providing compassion and sensitive care.[6] In their attempts at caring, male nurses are not seen as doing what 'real men' do. Therefore, they constantly have to defend their career choice.[7]

The perpetuation of hegemonic masculinities in society situates men as sexual aggressors or even as violent individuals.'81 Providing basic nursing care thus becomes a challenge for men, as they frequently feel their motivation to touch is viewed with suspicion, or that they risk being accused of sexual misconduct.[2,9] The sexual misconduct by some male nurses is of great concern in SA, where gender-based violence (GBV) is on the rise, along with alarming rape statistics regarding women and young girls,[10] with one woman in this country being killed by an intimate partner every 8 hours.[9] Many victims of GBV seek medical attention at healthcare institutions, where male nurses provide nursing care. Female nurses may identify with the trauma of their female patients, while male nurses may feel ashamed of the behaviour of the men who caused these women to be traumatised.[10]

Not all male nurses are sexual offenders. Men who enter the field of nursing should be seen as professionals who are capable of care.[6] Just as there are efforts to encourage women to study science, technology, engineering and mathematics,[10] there should be efforts to recruit men for the nursing profession to correct the gender imbalance. Nursing education programmes should guide students in understanding and navigating the influences that patriarchal structures and gender norms have on the nursing profession.[2] The purpose of the study was to gain in-depth insights into and an understanding of male nursing students' perceptions of the nursing profession.

Methods

Study design

Generic qualitative research was used to explore and describe male nursing students' perceptions of the nursing profession in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Province. This design allowed the researcher to capture the lived experiences and grasp details of the social world of male nursing students, as well as the meaning they ascribe to their experiences from their unique perspectives.[11]

Setting

The study was conducted at two selected public nursing education institutions (NEIs) in rural and suburban KZN.

Study population and sampling strategy

The population comprised male nursing students registered at two nursing campuses of the KwaZulu-Natal College of Nursing (KZNCN). A non-probability purposive sampling technique was used to select participants who could provide rich, thick information that would offer the researcher an in-depth understanding of and insight into[11] male nursing students' perceptions of their profession. The study participants were registered for the comprehensive nursing programme (R.425) and were between 21 and 44 years of age.

Data collection

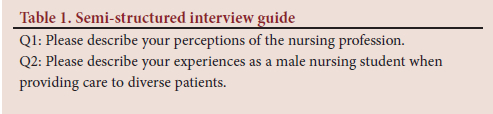

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and unstructured observation. During the semi-structured interviews, the researcher posed several open-ended questions based on the topic being studied.[12] Two specific questions were asked, and thereafter probing was used for a deeper understanding of the male student nurses' perceptions of their chosen profession (Table 1). The interview questions were refined after pilot testing with 2 male nursing students. Before conducting the interviews, the researcher provided the participants with a summary of the study, to enable them to give informed consent. The participants were informed that the interviews would be audiotaped, and confidentiality maintained. Sixteen male nursing students participated in 45-minute semi-structured individual interviews. Data were collected between May and August 2014.

Data analysis

Data were manually analysed using thematic analysis. A verbatim transcription was done of the audiotaped semi-structured interviews. The researcher immersed herself in the data to become familiar with the content. Initial codes were generated, after which the data supporting the codes were searched and the themes reviewed. Coding was done by aggregating the text into small categories of information, seeking evidence for each code from the data.[13] Then, the data were carefully read to identify clusters of concepts, and important concepts were labelled to formulate categories and themes.[12] The identified themes and sub-themes were reviewed and discussed with an independent co-coder.

Rigour

Rigour, which refers to the quality of qualitative inquiry, is used as a way of evaluating qualitative research.[11] Credibility was enhanced by purposively selecting participants for their knowledge and unique characteristics. To ensure transferability, rich, in-depth descriptions of participant responses were provided. Dependability was achieved by conducting semi-structured interviews and keeping an audit trail, where the researcher documented (in detail) the methodology, methods of data collection and linkage between the data and the findings. Confirmability was established by employing the services of an independent co-coder. The researcher and co-coder discussed and agreed on the presented themes and sub-themes.

Ethical approval

The researcher obtained ethical approval from the Health Studies Higher Degrees Committee, University of South Africa (ref. no. HSHDC/296/2014). Approval to conduct the study was also received from Health Research and Management, KZN Department of Health (ref. no. HRM29/14), KZNCN and the two selected NEIs. The researcher outlined the background, purpose, and objective of the study to the purposively selected male student nurses. Before commencement of the interviews, the participants signed informed consent forms. The real names of the NEIs and participants are not reflected in the study or this article.

Results

Demographic data

The participants were male nursing students enrolled for a 4-year diploma in the comprehensive nursing programme: general nursing sciences, psychiatry, community, and midwifery (R.425). The students were in their second and third academic levels and between the ages of 21 and 44 years.

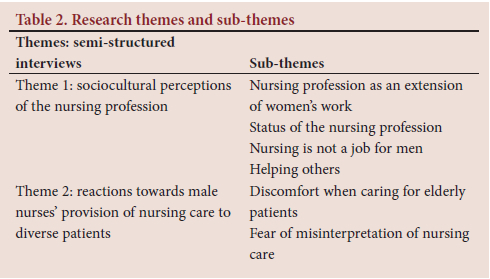

In the semi-structured interview, two main themes were developed (Table 2). The themes and sub-themes are discussed below.

Theme 1: Sociocultural perceptions of the nursing profession

The participants perceived the nursing profession as representing an extension of women's work, which includes caring for the sick, children and the needy. This perception is based on their backgrounds, which are rooted in cultural socialisation as black African men in KZN.

Nursing profession is an extension of women's work

The participants identified the disparate roles of women and men in their community/society. They felt that it was the role of women to deal with the body of a patient and provide hygiene-related care. A participant expressed his views as follows:

'My perception is that nursing is something that is for females ... .

Previously, I saw females working in nursing. In my culture, as a male, you are not allowed to see a naked old woman, so this is against my culture, so

that is why I believe it is for women only.' (M5-2014)

'I feel nursing is more for women because at home, caring for the sick is done by women, also giving birth and taking care of the family, as men we oversee things . .' (M6-2014)

'... it is more of women's work because as a nurse you clean up everybody's messes, patients, relatives, sometimes doctors in the ward do not even see you, just invisible.' (M1-2014)

Status of the nursing profession

In most societies in SA, women have inferior status. This inferiority influences the social and professional standing of a female-dominated profession, e.g. nursing. Some participants perceived nursing as a profession with low status. These perceptions were expressed as follows:

'... nursing is considered as work for everyone, which can be done by everyone, as it is part of motherhood ... , meaning every woman can do it, it is not a good job for men, not what you are doing ... .' (M5-2014) '... some think that in nursing you do not study, you just give bedpan, bath patients, etc. The only thing you do the whole day is to clean patients.' (M8-2014)

'Some [people in the community] use offensive names when you pass by; in our communities those who are drunk, they will use names . . They will say "You are dealing with faecal matter when you are at work, your job is to wipe people, especially the old people's bum . you are not a real man'.: (M1-2014)

'There are two or three times when I was travelling home in a bus wearing my white nurse's uniform, where the people in the bus, especially men, were saying embarrassing things and making fun of me . , this meant that men doing nursing are a joke to the society. I think people need to stop looking down [on] nursing and regard it with respect, maybe more men will join the profession as for now, they are afraid and looking down [on] nursing and thinking it is women's job.' (M2-2014)

One participant felt that some duties in nursing were not supposed to be done by men, as these are not part of what a man is expected to do:

'[There are] some aspects [of] the job that I feel should not be part of men's job description, [tasks like] for me giving [a] bedpan, pressure care and wiping women's back. From a cultural point of view, men are not supposed to be cleaning [up] after sick women and bathing children. If you are [doing] these tasks, it's like you are losing your manhood. .' (M2-2014)

Nursing is not a job for men

Men who choose nursing as a career run the risk of being stigmatised as weak, soft or homosexual. There is an assumption that men do not cry or, if they do, it must not happen in public. The participants shared the view that society sees them as 'half men' or homosexual. These opinions are expressed in the following comments:

'. nursing is not a male thing . . It is for soft people, people who are feeling for others, people who care, we tend to say men are strong people, we do not share our feeling.' (M9-2014)

'They [society] see male nurses as ... half men, they think ... [they] are gay because this is a profession for women, they are not full men . .' (M8-2014)

'The society where I come from as a male nurse, it is not good for me, as nursing is for females . . They consider those who are . nurses as homosexuals, gays. If you are enrolled in nursing, you will end up being a soft person who is not able to care for the patient as expected. You are set for failure because of your gender. Sometimes it is tough to be a male nurse.' (M7-2014)

Helping others

Male nurses choose nursing to help others. Nursing is a caring profession, which suggests that the partipants have the will to provide care to patients who need it.

'. to be able to provide help, nursing has given me a chance to help another person to feel better.' (M2-2014)

Theme 2: Reactions towards male nurses' provision of nursing care to diverse patients

Male nursing students are required to provide quality nursing care to diverse patients, regardless of their cultural, societal and religious affiliations. The majority of basic nursing care procedures involves being in physical contact with the naked body of a patient. Different cultural and religious beliefs ascribe accepted ways of caring for the human body. These beliefs may create a barrier during nursing care implementation.

Discomfort when nursing an elderly patient

The age of a patient plays a pivotal role in the provision of care. For the participants, providing care to patients of advanced age brought about discomfort, especially seeing them naked. Respecting elderly patients meant not seeing them naked, which may lead to bad luck. This is expressed as follows:

'I am an African young man, I was taught to respect my elderly. Caring for a female naked body is not a good thing for me. Imagine undressing and cleaning the body of an old lady? I respect her as my grandmother. In my culture, age plays an important role: an old person is like one's mother or father and seeing them naked is equivalent to disrespecting your parents.' (M1-2014)

'Caring for the naked body of an adult patient is a difficult thing. When I am delegated ... the task, I try by all means to change shift/the duty to someone else, because in my culture we tend to say that if you see someone's naked body, more especially the genital parts, you will have bad luck. You will have to go home and get a chicken to remove ubumnyama (darkness, bad luck).' (M12-2014)

Fear of misinterpretation of nursing care

In an era where there is a high prevalence of gender-based violence, male nursing students find it difficult to care for female patients. Their fears are justified as follows:

'There are procedures that I am not comfortable doing because I am a man, such as taking care [of], or looking at, the naked body of [a] patient of the opposite sex and same age . it is a disaster . , I am just scared.' (M15-2014)

'When caring for the patient, you have to screen [for privacy]; that makes me feel scared as I am alone behind the screen with a female patient, just the two of us. You don't know what they are thinking . .' (M10-2014) 'I need assistance from a female person to feel safe . , because of the lawsuits . these days. It is difficult to care for female patients, because privacy is needed when doing a procedure.' (M1-2014) 'A female [nurse] must be there to assure that the patient feels safe, because many people [female patients] have been raped, they are still scared when they are in the hospital. It is also for myself because I know I am going to be alone with her [female patient] and with the screening, being alone with the patient and no one knows what is happening there [behind the screen]. And women are highly respected and so the fault [blame] will be on me ... .' (M4-2014)

Male nurses provide care cautiously to avoid misinterpretation and protect themselves. Most participants expressed uneasiness in providing nursing care to female patients. They seek the assistance of female nurses to work as chaperones alongside them, as the following comments testify:

when I have to take care of the female [patient], I make sure that there is a female nurse to protect myself, and maybe the patient too ....' (M1-2014)

'I still feel that as a male nurse I need protection, I must have a female nurse to assist me ... .' (M3-2014)

'Life is tough out there, I must have someone who is going to back me up ... , a female nurse must be there. I feel safe having her to protect me and my future reference, should the patient feel otherwise.' (M4-2014)

The male student nurse participants reported providing cautious or defensive nursing care, which makes it difficult for them to provide quality care.

Discussion

The perception of nursing as an extension of women's work promotes gender discrimination against men, based on their perceived inability to care. The feminine classification of nursing has led to a minority of men entering the profession.[2] The recruitment of men in a nursing programme in a developed country has remained static at ~10%.[14] In 2017, 11% of nurses in the UK were male.[15] As noted, the status of the nursing profession remains based on gender dominance. Nursing is shaped by a patriarchal power structure that situates caregiving within the feminine realm and marginalises the caring acts of male nurses.[16] Traditional gender roles and norms are often imposed and reinforced in nursing education and practice, potentially limiting diversity and innovation in the profession.[17] Most male student nurses live in patriarchal societies that emphasise gender roles by clearly articulating what is expected of each gender. Men who choose nursing as a career are considered non-adherents to patriarchy, and their gender identity is questioned.[18]

The male nursing students who participated in this study considered the human body to be sacred. Basic nursing care requires male nurses to expose and touch the naked body of a patient.[19,20] The reaction of the patient and nurse to such touch is based on the age, gender and cultural background of the parties involved. As mentioned, SA continues to battle the scourge of GBV.[10] Many male nurses find it difficult to provide nursing care freely, without fear of being falsely accused of sexual violence by patients or their families.[20] In this study, many male nurses feared litigation, especially when caring for female patients. In one study, patients wanted male nurses to communicate with them, and to be given a chance to express a gender preference prior to being treated by a nurse.[21]

Men are expected to be strong, even rough and violent,[11] and these preconceptions lead to male nurses being classified as sexual perpetrators.[22] The SANC recorded 55 cases of poor nursing care and 3 of sexual assault during 2014 - 2019,[23] without stipulating the gender of those responsible for such misconduct. While there may be little reporting of sexual misconduct by male nurses, the media have reported incidences of male nurses being accused of heinous acts against young girls: in 2019, for instance, a male nurse appeared in court for allegedly murdering a 4-year-old girl.[24] Early in 2020, a 52-year-old male nurse was arrested for allegedly raping his 2-year-old stepdaughter.'251 These instances of sexual misconduct violate the ethical code of conduct of nursing professionals and confirm society's perception of male nurses as sexual perpetrators,[9,11] putting pressure on male nurses when they perform their caring functions.[6]

Male nurses resort to using strategies to protect themselves when providing care to diverse patients, especially women. The study participants admitted to being comfortable when providing care to female patients in the presence of a female nurse, as they feared being falsely accused of touching a patient inappropriately. As reported in one study, male nurses traded intimate care tasks with female colleagues and used female nurses as chaperones.'21 Some authors discourage the automatic use of chaperones, as it may lead to patients not trusting male nurses.[21] Many male nurses modify procedures to minimise touching or exposing patients.[22] They are forced to be cautious caregivers, as their care is often not accepted or is mistrusted by society.[7]

Male nurses enter the nursing profession to help people in need of care.[4] Gender profiles at NEIs should be revised to reflect the diversity of the population.'41 Male nurses can provide care in the service of humanity, in the same way as their female counterparts. They need to be allowed to excel at caring for others.

Study limitations

The study was conducted at two NEIs in rural and suburban KZN. The qualitative research approach was used, and therefore the results cannot be generalised.

Conclusion and recommendations

The recruitment of men will assist in curbing the shortage of nurses and will increase diversity. An inclusive curriculum is necessary to promote a gender-friendly and non-discriminatory teaching and learning environment. Male nurses are needed to serve as visible role models, who can coach and support male students. Their caring capacity should be evident to allow society to accept and appreciate the value they bring to the nursing profession. The actions of male nurses who jeopardise the profession must not be ignored. The SANC must continue with disciplinary action for all misconduct, following the legal prescripts of the country.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. I acknowledge the KZN Department of Health, the KZNCN and the two NEIs for permitting the study to be conducted. I thank the nursing students who participated in the study.

Author contributions. Sole author.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Al-Momani MM. Difficulties encountered by final-year male nursing students in their internship programmes. Malay J Med Sci 2017;24(4):30-38. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2017.24A4 [ Links ]

2. Kellett P, Gregory DM, Evans J. Patriarchal paradox: Gender performance and men's nursing careers. Gend Manag 2014;29(2):77-90. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-06-2013-0063 [ Links ]

3. South African Nursing Council. Provincial distribution of nursing manpower versus the population of the Republic of South Africa as at 31 December 2019. https://www.sanc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Stats-2019-1-Provincial-Distribution.pdf (accessed 4 October 2022). [ Links ]

4. Harding T, Jamieson I, Withington J, Hudson D, Dixon A. Attracting men to nursing: Is graduate entry an answer? Nurse Educ Pract 2018;28:257-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.07.003 [ Links ]

5. Smith P. The Emotional Labour of Nursing Revisited: Can Nurses Still Care? 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. [ Links ]

6. Mohamed LK, Mohamed YM. Role strain of undergraduate male nurse students during learning experience in nursing education programs. J Nurs Educ Pract 2015;5(3):94-101. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v5n3p94 [ Links ]

7. Mahadeen A, Abushaikha L, Habashneh S. Educational experiences of undergraduate male nursing students: A focus group study. Open J Nurs 2017;7(1):50-57. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2017.71005 [ Links ]

8. Ross DJ. Perceptions of men in the nursing profession: Historical and contemporary issues. Links Heal Soc Care 2017;2(1):4-20. [ Links ]

9. Morrell R, Jewkes R, Lindegger G. Hegemonic masculinity/masculinities in South Africa: Culture, power, and gender politics. Men Masc 2012;15(1):11-30. [ Links ]

10. Van Wyk N, van der Wath A. Two male nurses' experiences of caring for female patients after intimate partner violence: A South African perspective. Contemp Nurse 2015;50(1):94-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2015.1010254 [ Links ]

11. Liamputtong P. Qualitative Reseach Methods. New Zealand: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

12. Polit DF, Beck CT. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2017. [ Links ]

13. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2013. [ Links ]

14. Gavine A, Carson M, Eccles J, Whitford HM. Barriers and facilitators to recruiting and retaining men on pre-registration nursing programmes in Western countries: A systemised rapid review. Nurse Educ Today 2020;88:1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104368 [ Links ]

15. Clifton A, Higman J, Stephenson J, Navarro AR, Welyczko N. The role of universities in attracting male students to pre-registration nursing programmes: An electronic survey of UK higher education institutions. Nurse Educ Today 2018;71:111-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.09.009 [ Links ]

16. Powers K, Herron EK, Sheeler C, Sain A. The lived experience of being a male nursing student: Implications for student retention and success. J Prof Nurs 2018;34(6):475-482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.04.002 [ Links ]

17. Burton CW. Paying the caring tax: The detrimental influences of gender expectations on the development ofnursing education and science. Adv Nurs Sci 2020;43(3):266-277. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000319 [ Links ]

18. Abbas S, Zakar R, Fischer F. Qualitative study of socio-cultural challenges in the nursing profession in Pakistan. BMC Nurs 2020;19(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00417-x [ Links ]

19. Shakwane S, Mokoboto-Zwane S. Demystifying sexual connotations: A model for facilitating the teaching of intimate care to nursing students in South Africa. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2020;12(3):103. https://doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2020.v12i3.1367 [ Links ]

20. O'Lynn C, Cooper A, Blackwell L. Perceptions, experiences and preferences of patients receiving the clinician's touch during intimate care and procedures: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2016;14(6):96-102. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-002698 [ Links ]

21. O'Lynn C, Krautscheid L. 'How should I touch you?': A qualitative study of attitudes on intimate touch in nursing care. Am J Nurs 2011;111(3):24-31. https://doi.org/10.1097/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000395237.83851.79 [ Links ]

22. Jordal K, Heggen K. Masculinity and nursing care: A narrative analysis of male students' stories about care. Nurse Educ Pract 2015;15(6):409-414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.05.002 [ Links ]

23. South African Nursing Council. Statistics: Professional misconduct cases. https://www.sanc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Disciplinary-Stats-2014.pdf (accessed 4 October 2022). [ Links ]

24. African News Agency. Male nurse due in court for murder of four-year-old girl. ANA, 26 July 2019. https://www.lol.co.za/news/south-africa/northwest/male-nurse-due-in-court-for-murder-of-four-year-old-girl-29889898 (accessed 6 October 2022). [ Links ]

25. Serra G. Nurse, 52, arrested after allegedly raping two-year-old stepdaughter. IOL, 3 February 2020. https://www.iol.co.za/new/south-africa/western-cape/nurse-52-arrested-after-allegedly-raping-two-year-old-stepdaughter-42043234 (accessed 7 August 2021). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Shakwane

shakws@unisa.ac.zd

Accepted 13 April 2022