Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.14 no.3 Pretoria Set. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2022.v14i3.1281

RESEARCH

A case study: Promoting interprofessional community-based learning opportunities for health sciences students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

I Moodley; S Singh

PhD Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Preventing disease and promoting health call for interprofessional collaboration of health professionals working in a team, making it important for student health professionals to experience collaborative teamwork while in training, rather than learning and working in silos.

OBJECTIVES. To describe the opinions of participating students and supervising staff in an intraprofessional community-based initiative involving the disciplines of physiotherapy and dentistry at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Durban, South Africa.

METHODS. This was a qualitative descriptive study demonstrating teamwork of students from two health sciences disciplines, giving a joint health education talk to patients at a local community health centre. Data were collected from focus group discussions. Three such discussions were held with purposively selected samples: (i) 5 physiotherapy students; (ii) 6 dental therapy students; and (iii) 6 staff members from both disciplines who supervised the students. These data were analysed using thematic analysis. Ethical approval was obtained from UKZN.

RESULTS. By working collaboratively, the students believed that they learnt more about the other health professionals and obtained a deeper understanding of their roles within the healthcare team. Staff believed that the collaborative project could break down professional barriers to work cohesively in the work environment. The main difficulties encountered were the language barrier and rigid timetables.

CONCLUSION. This case study provides an example of intraprofessional collaboration and teamwork, capable of positively influencing participating students, emphasising the need for interprofessional learning opportunities for students across all health sciences disciplines while in training.

There is growing support in the literature regarding the effectiveness of community-based approaches for improving the health of individuals and populations,[1] specifically if these include health-promotion interventions. Furthermore, culturally appropriate community-based oral health-promotion initiatives may lead to measurable improvements in oral health,[2] making it important to include this component in general healthcare-promotion activities. Preventing disease and promoting health call for interprofessional collaboration of health professionals working in a team,[1] emphasising the need for student health professionals to experience collaborative teamwork while in training; however, health professionals commonly work in silos.

Interprofessional education (IPE) occurs when students 'from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes'.[3] IPE provides opportunities to build relationships, interconnections and interdependence to ensure a patient-centred approach where team members offer services, education and coaching to obtain optimal patient results.[4] In so doing, there is a transition in service delivery from a fragmented to an integrated approach, where patient care is comprehensive and tailored.[4] Higher education institutions play an important role in providing opportunities for student health professionals to create a foundation and gain exposure to interprofessional collaboration before entering the workforce.[5] However, it is often difficult to incorporate and implement formal interprofessional learning opportunities into curricula across the disciplines.

The College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Durban, South Africa, has a broad mix of health professional students, including doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, optometrists, pharmacists, audiologists, dental therapists, speech language pathologists and sport scientists, which provides a unique opportunity for shared learning. Clinical training in these disciplines occur at campus clinics and designated off-campus sites. Although community-based education (CBE) is fundamental to most disciplines in the health sciences, it is often practised independently. While interprofessional collaborative projects occur within a few of the disciplines at a primary healthcare centre (PHC), the Discipline of Dentistry has not been included, indicating a need for such an opportunity.

The disciplines of physiotherapy and dentistry both conduct community-based clinical training for their third-year students at a nearby community health centre (CHC). The physiotherapy students' scope of practice includes assessing and treating human movement disorders to restore normal function in adults and children, using skilled hands-on therapy such as mobilisation, manipulation, massage and individually designed exercise programmes. Their scope of practice also contributes towards preventing recurring injuries, disability in the workplace and at home, and promoting community health for people of all age groups. The physiotherapy students attend the CHC in groups of 6, for 4 hours daily, in a 5-week rotation. At the site, their activities include managing patients in the physiotherapy department under supervision, providing health education, health promotion and group therapy sessions, undertaking a community-based project and visiting outlying clinics and homes.

The Discipline of Dentistry trains dental therapy students, whose scope of practice includes preventive and curative oral healthcare through procedures such as dental examinations, diagnosis of common oral diseases, scaling and polishing, placement of direct restorations and tooth extractions. A focus area includes oral health education and promotion on an individual and community level. As part of a community-based initiative, the dental therapy students attend the same clinic, with 8 students attending simultaneously on a once-weekly basis for 4 hours. Students rotate each week so that all of them are exposed to the community-based clinical training. Their activities include oral health education to patients and working under supervision in the dental department, performing procedures such as clinical examination, diagnosis, tooth extractions and referral. An academic from each discipline accompanies them to supervise their activities. However, this is done separately and in their respective departments.

The researcher, an academic from the Discipline of Dentistry, seeking an opportunity for interprofessional collaboration, approached the academics from both disciplines to initiate a joint IPE intervention project. In so doing, intraprofessional collaboration and teamwork between 2 student professionals can be initiated for a common goal of better health and wellbeing of patients at the CHC.[6] The researcher and the academic from physiotherapy, taking on the roles of drivers and facilitators, approached the students from the two disciplines as a group and explained the plan.

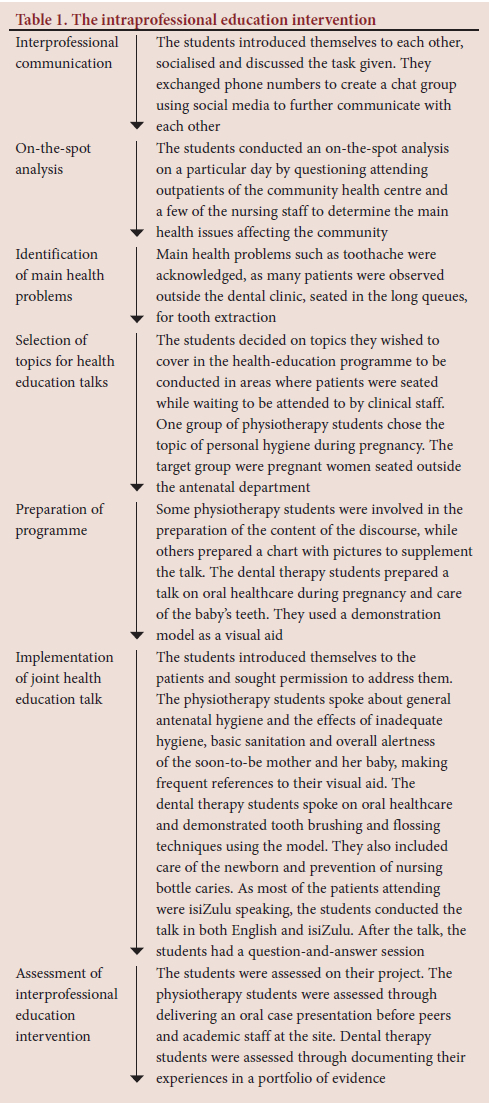

The intraprofessional intervention

The students collaborated with each other to provide a health education talk to patients at the CHC (Table 1).

Health education forms an important part of health-promotion activities and is defined as a constructive opportunity for improving knowledge and life skills at schools, workplaces, clinics and communities, conducive to community needs, through some form of communication.[7] The settings approach is being widely adopted for health promotion, as it contextualises health education topics to the needs of specific communities.[8] The primary healthcare setting can be viewed as an effective means of reaching a large section of the community, including pregnant women, young children and patients with chronic diseases.

This study describes the views of participants of an intraprofessional learning experience between dental therapy and physiotherapy students in the School of Health Sciences, UKZN, with the intention of promoting teamwork and interprofessional collaboration among the students, academics and clinical staff.

Methods

Research design

This was a qualitative descriptive study in which students of two health sciences disciplines participated in an intraprofessional intervention. Their views were obtained through focus group discussions. This case study of teamwork was part of a larger study on CBE in the School of Health Sciences, conducted in 2017.

Participants

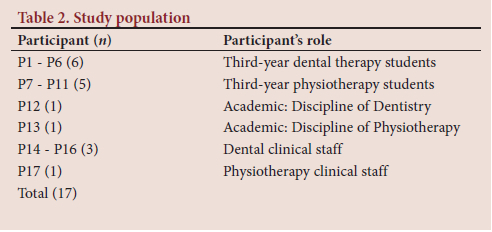

The researcher used a purposive sampling method to select the study sample. The study population consisted of 50 physiotherapy and 36 dental therapy students registered for their third academic year, as well as academics and clinical staff of the CHC. However, the student sample population consisted only of those who participated in the CBE rotation at the CHC from March to May 2017 (18 physiotherapy and 24 dental therapy students). The 2 academics, 1 from each discipline, who accompanied the students to the site, and the 4 clinical staff from the two departments in the CHC, who supervised their training, were included. The researcher approached participants individually, inviting them to participate in an interview and obtaining their consent. The final sample size consisted of 17 participants (Table 2) and was given a code name from P1 to P17 to maintain anonymity.

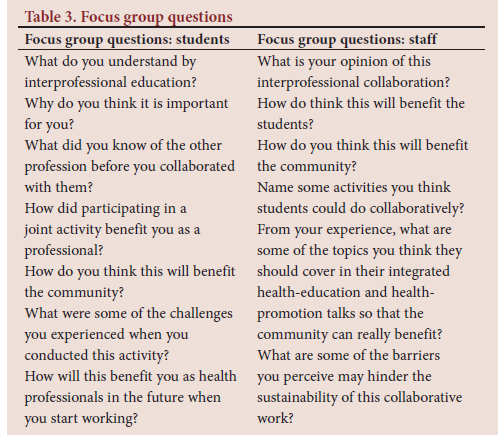

Data collection

The researcher facilitated two student focus group discussions, one from each discipline, each lasting ~60 minutes, to obtain feedback on students' perceptions of the intraprofessional collaboration. The first discussion included 5 students from the Discipline of Physiotherapy, and the second, 6 students from the Discipline of Dentistry, using an interview schedule to guide the discussions (Table 3, column 1). These focus group discussions were conducted in a relaxed environment of a boardroom in the Discipline of Dentistry in the presence of a research consultant, who made field notes during the discussions. It was a closed boardroom to ensure privacy.

The researcher conducted a third focus group discussion with the academic and clinical staff to obtain their perspectives of the student collaboration, at a closed private office in the dental department of the CHC, using a separate set of questions (Table 3, column 2).

The researcher audiotaped focus group discussions with the consent of the participants. A research assistant transcribed the data verbatim and later cleaned the data. The research consultant assisted with the thematic analysis. The theoretical position of the thematic analysis adopted a 'contextualist' method, which acknowledges the ways individuals make meaning of their experiences and how this meaning can have a broader social impact.[9] The researcher and the consultant independently read the transcripts across all three focus group data sets, using an inductive approach to identify familiar patterns.[9] Initial coding of familiar patterns was done manually by writing notes on the transcripts, linking the relevant extracted data to each pattern. Several open codes were merged into three large overarching themes and the extracted data were collated into each identified theme. The main themes were then reviewed and several sub-themes emerged, which were further refined to form a coherent pattern within a main theme.[9]

The research established credibility, attesting to internal validity in qualitative research, by using focus group discussions with various participants to obtain the data. Credibility was further established through peer debriefing, which was undertaken by another member of the research team, who reviewed the data collection methods and processes, transcripts and data analysis procedures, and provided guidance to enhance the quality of the research findings.[9] Transferability, relating to external validity, was facilitated with a purposively selected sample and by providing a rich description of the context of the enquiry.[9] Transferability was further enhanced by comparing research findings with the current literature. Dependability was achieved through the use of member checks, where the analysed data were sent to 2 participants from each focus group to evaluate the researcher's interpretations and to provide feedback.[9] The researcher and the research consultant analysed the same data and compared the results, further enhancing dependability. By quoting actual dialogue of the respondents, confirmability was established. Participant confidentiality and anonymity were maintained.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Committee, UKZN (ref. no. HSS/1060/015D).

Results

Three overarching themes emerged from the data analysis process: benefits for student education; professional development of students; and challenges to implementation.

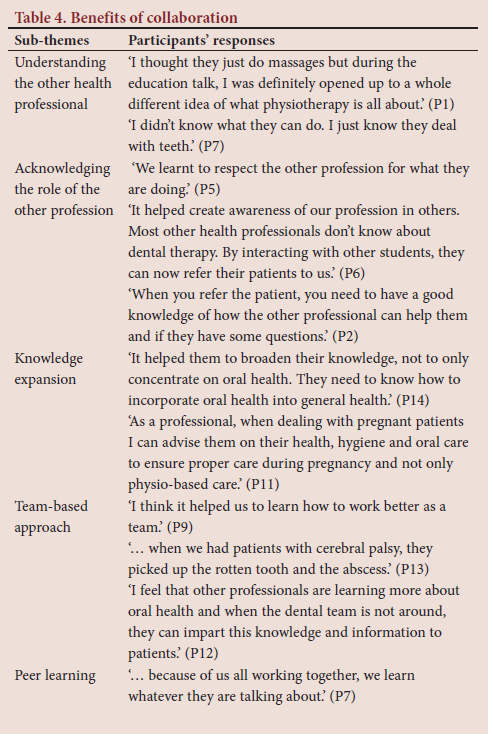

Theme 1: Benefits for student education

The collaboration had a positive impact on both groups of students. They shared learning experiences and a deeper appreciation for the other profession (Table 4).

Theme 2: Professional development of students

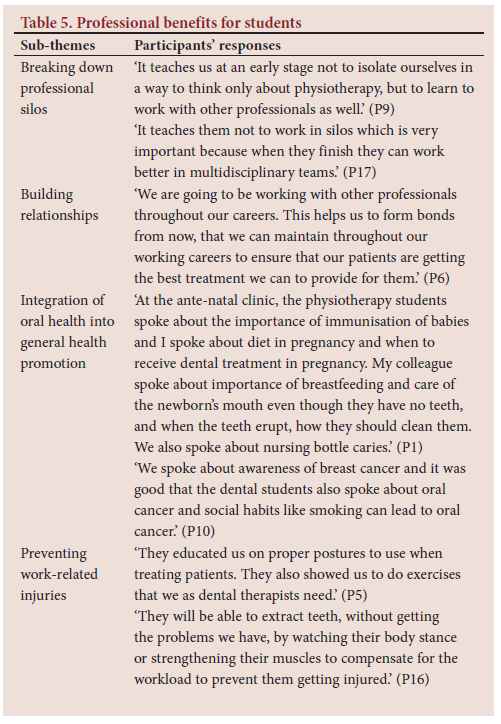

Students believed they could benefit by building professional relationships that would provide integrated patient management, making appropriate referrals (Table 5).

Theme 3: Challenges to implementation

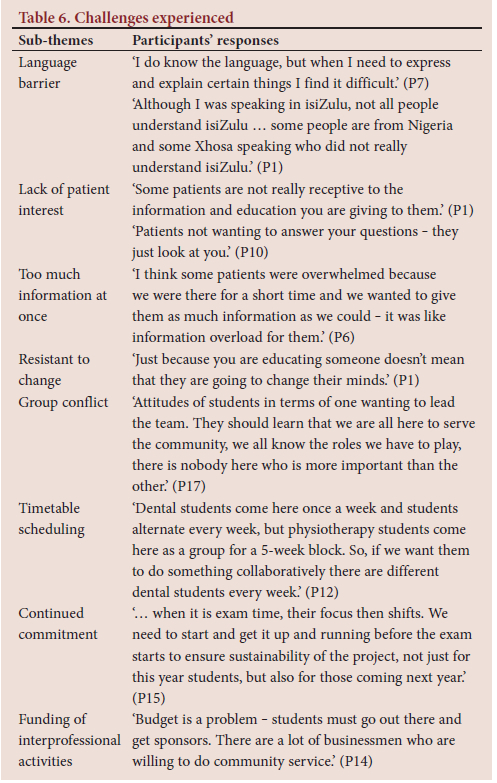

Students encountered a few difficulties while undertaking this collaborative project (Table 6).

Discussion

Health education forms an essential component of student training and is embedded in curricula across all disciplines of the health sciences.[10] Early exposure to community settings familiarises student professionals with the culture of health promotion and disease prevention.[10] However, this should not be done in insolation as individual disciplines, but collaboratively with other student health professionals for maximum benefits to the communities they serve. This case study is an example of the merger of education and service and demonstrates students' openness and readiness to participate in interprofessional activities. Working in a team in this initiative familiarises students with one other profession; however, it serves as a model to expand these learning opportunities to include multiple professions within the health sciences.

The intention of the collaborative initiative was to increase awareness and knowledge among patients. In developing countries, IPE activities should adopt a tailored approach aimed at solving the main health problems of a target community, being culturally appropriate and delivered in a way that is easily understood.[8] It must also be able to improve knowledge to inform lifestyle habits.[8,11] The joint health education talk delivered by the students in both English and isiZulu was planned according to the needs of a particular community, demonstrating relevance and alignment to the current literature. It also demonstrates application of PHC principles, specifically to identify needs through community participation and implementing interventions using available resources to address these health issues. This is further supported by Ndateba et al.,[12] who claim that the approach of first identifying healthcare problems and validating the needs of communities through appropriate interventions is in line with PHC philosophy. In this initiative, students put into practice the theory of PHC principles learnt. Improving access to health information should lead to patients using this information to promote and maintain good health.[8] It is hoped that this result will be seen in the long term.

Furthermore, this initiative sets oral health promotion in the broader context of general health promotion and highlights the need for a multidisciplinary approach to achieve better health outcomes of communities. The commonality of risk factors for oral diseases and general health diseases is demonstrated and emphasises the need to include oral health as a topic in general health-promotion and disease-prevention strategies.[13] This study shows the effective integration of oral health topics into general health-promotion topics, as observed when students spoke on personal hygiene for pregnant women. The dental students spoke about oral hygiene during pregnancy and extended it to oral healthcare of the newborn.

From the information obtained, students believed that the collaboration was valuable and that they benefited considerably. They learnt about each other and with each other, developing greater respect for the other profession. They believed that by learning together they could improve postgraduate working relationships. By breaking down professional silos, they learnt the value of a team approach in the holistic management of patients. This approach is supported by the literature that demonstrates that IPE is an effective tool in developing collaboration and improving professional practice among health professionals.[11] Moreover, the experience of learning together can break down professional walls, change attitudes and reduce stereotypes.[11]

While working in a team, the students established links with other professions that could develop into future professional relationships in the work environment, especially in making appropriate referrals. VanderWielen et al.[14] support networking as an important component in interprofessional collaborative practice in holistic patient care.

The dental therapy students also realised that physiotherapy students could help them in ways that they did not anticipate, i.e. to prevent work-related injuries through the practice of exercises. The dental staff at the clinic were suffering from pain that related to some form of musculosketal disorder (MSD). The prevalence of MSDs is well documented in the literature, with a study conducted in KZN indicating that 080% of dentists reported pain in their hands, neck, shoulder and lower back due to clinical work. The study suggested the need for ergonomic work practice while in training to reduce the risks of MSDs later in their working careers.[15] The current study shows that students become aware of the risk of MSD through the experiences of the dental clinical staff 0 they should heed their advice and practise the exercises shown to them by the physiotherapy students to prevent future occurrence of MSDs.

The main challenge experienced in the current study, was the language barrier when participating students communicated with patients. Most members of the community were isiZulu speaking. Student grouping consisted of a good mix of students from diverse cultural backgrounds and ensured that the health education talks were presented in both English and isiZulu. This approach is further supported by the literature, which reports that effective communication between healthcare provider and patient is regarded as fundamental in providing quality healthcare, leading to patient satisfaction and health improvement through acceptance, compliance and co-operation.[16] However, this did not affect the ability to conduct the interprofessional intervention.

An important lesson learnt from this study was to limit the amount of information given to patients at any given time. Only the most important facts that students want patients to remember and take home should be mentioned. In the focus group discussion, a student suggested that pamphlets should be put together for patients to reinforce information, to take home and to read at their leisure. Students should also stimulate patient interest by involving them in an activity, as suggested by a participant. Patients should first demonstrate how they brush their teeth or wash their hands at home 0 then students could point out the patients' incorrect approach by demonstrating the correct way, which they would remember better when they are at home. In this way, they may be motivated to change their behaviour and habits.

The obstacles to sustainability found in this study were similar to those observed in previous studies. Time and scheduling are major obstacles for the implementation of IPE activities, as noted by Sungunya et al.[17] in a systematic review. To overcome this, some academics partially integrate IPE activities in the existing curriculum. Another solution is to make rigid curricula a little more flexible by allowing students to participate in other activities while participating in IPE activities.[17] To overcome the timetable barrier in this study, academics from the two disciplines should meet and discuss how they can best integrate an IPE activity into individual timetables to ensure its success and sustainability.

Lack of funding is also an important barrier to initiation and sustainability of IPE activities.[17] Funding is important for curriculum development, payment of costs and staff training to manage different health professional students; this should be the responsibility of the educational institution.[17 In this study, participants felt that students should be involved in generating funding for IPE projects. In this way, it becomes a student-centred approach, where students plan, fund and implement their own IPE activities.[17 By taking ownership, enthusiasm and sustainability for the activity will be improved.[17]

Conflicts arising within the group can complicate IPE. To overcome attitudinal issues in the group, students should be orientated by facilitators on the greater value and outcomes of IPE and they should be encouraged to see all members of the group as equal participants.[17] Kruger et al.[18] further support this by noting that students should be prepared for what is expected from them.

Study strengths and limitations

Study strengths include the openness and readiness of student health professionals to participate in intraprofessional initiatives. This research serves as a case study to further explore interprofessional collaborative initiatives across all disciplines in the School of Health Sciences. It further illustrates that even a simple intraprofessional activity, such as joint health education talks, can have meaningful experiences for students of both disciplines, emphasising the need for teamwork. From this study, it is noted that academic staff are drivers of such initiatives and should continue to promote the collaborative culture through creation of more IPE learning opportunities. It is acknowledged that the collaboration was limited to only two disciplines in the health sciences. The findings related to the views and opinions of the participants are therefore limited in their generalisability. Further research involving collaborations across more disciplines is required to promote IPE activities within the university.

Conclusion

This article provides a case study of intraprofessional collaboration and teamwork capable of yielding positive influences on participating students, emphasising the need for interprofessional learning opportunities for students across all health sciences disciplines while in training. It provides a basis for dental students to further explore interprofessional collaboration with multiple disciplines of the health sciences. Academics from the various disciplines play a vital role in creating and facilitating such collaborative learning opportunities. However, smooth implementation necessitates commitment from academics and teamwork from participating students.

Declaration. The research for this study was done in partial fulfilment of the requirements for I Moodley's PhD degree at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Acknowledgements. The authors acknowledge the active participation and contribution of the students and staff of the Discipline of Physiotherapy, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Author contributions. IM was responsible for conceptualisation, data collection, data analysis and interpretation. SS was responsible for refining the methodology, overseeing the write-up and critical review of scientific data.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [ Links ]

2. Mathu-Muju KR, McLeod J, Walker ML, et al. The children's oral health initiative: An intervention to address the challenges of dental caries in early childhood in Canada's First Nation and Inuit communities. Can J Public Health 2016;107:e188-e193. https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.107.5299 [ Links ]

3. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, DC: IEC, 2011. [ Links ]

4. Nesta J. The importance of interprofessional practice and education in the era of accountable care. North Carolina Med J 2016;77(2):128-132. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.77.2.128 [ Links ]

5. Buring SM, Bhusan A, Broeseker A, et al. Interprofessional education: Definitions, student competencies and guidelines for implementation. Am J Pharmaceut Educ 2009;73(4):1-8. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj730459 [ Links ]

6. Reeves S. Ideas for the development of the interprofessional education and practice field: An update. J Interprof Care 2016;30(4):405-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1197735 [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. Health Education: Theoretical Concepts, Effective Strategies and Core Competencies: A Foundation Document to Guide Capacity Development of Health Educators. Geneva: WHO, 2012. [ Links ]

8. Poland B, Krupa G, McCall D. Settings for health promotion: An analytic framework to guide interventions, design and implementation. Health Promotion Practice 2009;10(4):505-516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909341025 [ Links ]

9. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2010;3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

10. Whitehead D. Exploring health promotion and health education in nursing. Nurs Stand 2018. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11220 [ Links ]

11. National Department of Health. The National Health Promotion Policy and Strategy, 2015 - 2019. Pretoria: NDoH, 2019. [ Links ]

12. Ndateba I, Mtshali F, Mthembu SZ. Promotion of a primary healthcare philosophy in a community-based nursing education programme from students' perspectives. Afr J Health Professionals Educ 2015;7(2):190-193. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.399 [ Links ]

13. Sheiham A, Watt RG. Integrating the common risk factor approach into a social determinants framework. Comm Dentistry Oral Epidemiol 2012;40(4):289-296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00680 [ Links ]

14. VanderWielen LM, Do EK, Diallo HI, et al. Interprofessional collaboration led by health professional students: A case study of the Inter Health Professional Alliance of Virginia Commonwealth University. J Res Interprof Pract Educ 2014;3(3):1-13. https://doi.org/10.22230/jripe.2014v3n3a132 [ Links ]

15. Moodley R, Naidoo S. The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Dent J 2015;70(3):98-103. [ Links ]

16. Norouzinia R, Aghabarari M, Shiri M, et al. Communication barriers perceived by nurses and patients. Glob J Health Sci 2016;8(6):65-74. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p65 [ Links ]

17. Sunguya BF, Hinthong W, Jimba M, et al. Interprofessional education for whom? Challenges and lessons learned from its implementation in developed countries and their application to developing countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014;9(5):e96724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096724 [ Links ]

18. Kruger SB, Nel MM, van Zyl GJ. Implementing and managing community-based education and service learning in undergraduate health sciences programmes: Students' perspectives. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2015;7(2):161-164. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.333 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

I Moodley

moodleyil@ukzn.ac.za

Accepted 28 October 2021