Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.14 n.1 Pretoria Mar. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2021.v14i2.1471

RESEARCH

Using log diaries to examine the activities of final-year medical students at decentralised training platforms of four South African universities

A DreyerI; L C RispelII

IMPH; Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Division of Rural Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIPhD; Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Division of Rural Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: An important strategy in the transformation and scaling up of medical education is the inclusion and utilisation of decentralised training platforms (DTPs

OBJECTIVE: In light of the dearth of research on the activities of medical students at DTPs, the purpose of this study was to determine how final-year medical students spent their time during the integrated primary care (IPC) rotation at a DTP

METHODS: The study was conducted at Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (SMU), the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) and Walter Sisulu University (WSU). At each of the participating universities, a voluntary group of final-year medical students completed a log diary by entering all activities for a period of 1 week during the IPC rotation. The log diary contained five activity codes: clinical time teaching time, skill time, community time and free time, with each subdivided into additional categories. The data were analysed for students at each university separately, using frequencies and proportions

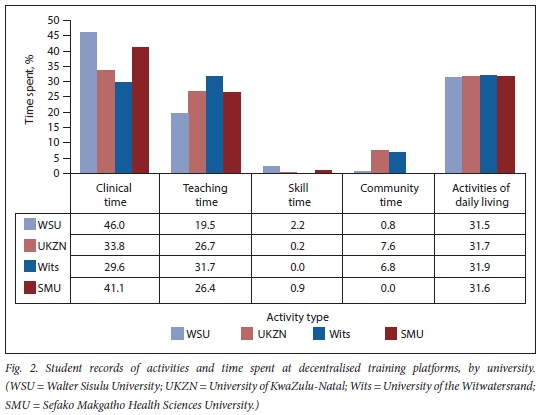

RESULTS: A total of 60 students volunteered to complete the diaries: at WSU n=21; UKZN n=11; Wits n=18; and SMU n=10. At each university, students reported that they spent large amounts of time on clinical activities: WSU=46.0%; UKZN=33.8%; Wits=29.6%; and SMU=44.1%. They reported low amounts of time spent on community-based activities: WSU 0.8%; UKZN 7.6%; Wits 6.8%; and SMU 0.0%

CONCLUSION: Students reported that they spent a sizeable proportion of their time on clinical activities, while reported time spent on community-based activities was negligible. The transformation potential of DTPs will only be realised when students spend more time on community-based activities

The inclusion and utilisation of decentralised training platforms (DTPs) are important in the transformation and scaling-up of medical education to overcome shortages, address inequities and support universal health coverage (UHC).[1] DTPs refer to any education or learning environment outside a tertiary hospital and the main university campus, and include a primary healthcare (PHC) facility, district or regional hospital, or non-governmental or community-based organisation that is used for health professional education and training.[2] In concert with global developments, the Academy of Science of South Africa (SA) has underscored the importance of decentralised training of health professionals,[3] while several scholars have highlighted the transformational potential of DTPs in increasing medical graduate output and improving outcome competencies.[2,4] Notwithstanding an encouraging increase in the scholarly focus on DTPs,[4-7] there is a dearth of research on DTPs in SA, especially on the activities of medical students and the time spent on these activities.

Log diaries or logbooks have been used extensively in educational research to document the range of clinical exposure and learning opportunities available to undergraduate medical students, and the quality of these learning encounters.[8-16] These log diary studies have demonstrated the value of community-based education,[16] and the patient demography, clinical content and process of general practice.[10,12,13,15] However, the majority of these studies have been conducted in Australia, Canada, the UK and the USA.

In sub-Saharan Africa, very few log diary studies on undergraduate medical education could be found. As part of a larger study on medical students' and junior doctors' preparedness for the reality of practice in Mozambique, Frambach et al.[17] used log diaries with the junior doctors. The study found that the six junior doctors who completed the log diary highlighted the challenges that they faced in balancing the need for healthcare delivery with personal survival.[17] The methodology for the study among medical students was a survey, rather than log diaries. In SA, a 2008 log diary study examined the perceived educational value and enjoyment of a rural clinical rotation for medical students.[18] Completed by 25 medical students, the study found that well-functioning rural healthcare centres contributed to skills development required for general practice and working in resource-limited settings.[18]

We could not find published studies since 2008 that have used log diaries to examine the activities of final-year medical students at DTPs. These final-year students are expected to complete integrated primary care (IPC) rotations at various DTPs in the majority of undergraduate medical education programmes in SA. The DTPs tend to be district or small regional hospitals but include a network of PHC facilities and community-based activities. The duration of the IPC blocks varies from 6 to 12 weeks.[19] Notwithstanding minor variations, the IPC objectives are similar across the different universities, namely that final-year students can provide person-centred curative care and develop competencies in general practice, disease prevention and health maintenance. [21,22,26]

The purpose of this study was twofold: firstly, to quantify how final-year medical students spent their time during the IPC rotation at a DTP; and secondly, to determine student perceptions of the educational value of the various activities. The study is part of a broader doctoral study that aims to analyse and compare DTPs and their utilisation in undergraduate medical education at four SA universities.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at four SA universities: Walter Sisulu University (WSU) in the Eastern Cape Province; the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) in KwaZulu-Natal Province; the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Gauteng Province; and the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (SMU) in Gauteng Province. The study sites have been described elsewhere.[22]

Study design

This was an educational research study, comprising a quantitative analysis of the log diaries of final-year medical students at the four participating universities.

Selection of participants

The original plan was to ensure diversity for the log diary study, and to recruit a random sample of final-year medical students from a list of purposively selected DTPs used for the IPC rotation at each participating university. Prior to study commencement and to assist data collection, the principal researcher (AD) consulted extensively with academic class co-ordinators and medical student representatives at each university. The consultation revealed that the planned approach of random selection was unlikely to work in practice. Hence the approach to student selection was changed. Firstly, the principal researcher selected the period between June and October 2018 to ensure that the data collection did not interfere with student examination preparation. Secondly, the principal researcher requested medical students to volunteer to keep the log diaries during the IPC rotation. This request was sent out through the various student communication channels, and the student representatives. The principal researcher liaised with the student representatives, who agreed to distribute the request for voluntary participation, together with the contact details of the principal researcher. Following the request for voluntary study participation, interested students at each university made contact with the principal researcher.

Development of data collection instrument

Following a review of the literature, the 2001 log diary tool of Murray et al.[13] was adapted, as it was available in the public domain, and contained all the possible categories of student activities engaged in when completing rotations at the DTPs. We developed an electronic version of the log diary for direct uploading onto RedCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University, USA),[20] a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. The log diary was divided into hourly activities, recording a 24-hour period. The log diary contained five activity codes, derived from the IPC learning activities:

A = clinical time; B = teaching time; C = skill time; D = community time and E = free time or activities of daily living. For each of these activity codes, a further coded breakdown was recorded in the log diary. The students also had to record whether the clinical activity was supervised, and who did the supervision. In the log diary, students were requested to indicate their perceptions of the educational value of the activity, the skills acquired during the activity, a rating of activity enjoyment, and whether the skills could have been acquired in the classroom at the main campus.

The electronic diary was piloted with five final-year students at Wits University, outside the planned data collection period. The pilot identified various problems, such as the looping and repetitive nature of the information that could affect participation and the completion of the log diary. The students suggested a paper-based version of the log diary. Hence, each day was condensed to fit onto one sheet of A4 paper size. Fields that were repetitive were converted into tick boxes for ease of completion. The aim of the tick boxes was to minimise errors during recording of activities. An example of the final log diary is shown in Fig. 1.

Data collection

Once the students had volunteered for study participation, the principal researcher emailed them the study information letter and consent form. Once the consent form was returned, a copy of the log diary was forwarded electronically. At WSU, the principal researcher arranged that a printed log diary be collected from a central point at the university prior to leaving the main campus for the DTP rotation. Some students requested an electronic copy of the log diary, which was emailed to them.

Each student also received a brief set of guidelines for completing the log diary. Students were instructed to exclude the first rotation week at the DTP when completing the diary, as the first week is often used for orientation activities and is not a true reflection of the IPC rotation. The log diary focused on the 7 days of the second week, when they were requested to record their activities in the log diary.

Data analysis

The hard and electronic copies of students' log diaries were stored in a locked, secure cupboard and on a password-protected computer, respectively. Each diary was assigned a number code to prepare for analysis and to ensure confidentiality. The diaries were grouped by university to allow for comparisons. The information in the completed diaries was captured using REDCap, and then exported to Stata version 16 (StataCorp, USA) for analysis. Only descriptive analysis was conducted.

Although students used a 24-hour period to record activities, we used a 10-hour day from 08h00 to 18h00 as a typical final-year medical student day. The activity code E (free time), which includes sleeping, daily ablutions and travelling, was renamed activities of daily living. Ratings of enjoyment and educational value were analysed as continuous variables on a three-point scale: great value, some value or no value.

Ethical considerations

The Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) Medical of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg provided ethical approval for the study (ref. no. M170704). Given the deviation from the original study protocol for the recruitment of students, the principal researcher obtained an amendment from the Wits HREC. All ethical guidelines were adhered to, including a detailed information sheet, informed consent, voluntary participation, confidentiality and anonymity of respondents.

Results

Background characteristics

Across the four universities, 60 students volunteered to complete the diaries: 21 students from WSU (1 female, 20 male); 11 students from

UKZN (8 female, 3 male); 18 students from Wits (8 female, 10 male); and 10 students from SMU (4 female, 6 male). During the data collection period, UKZN and SMU experienced student protests, resulting in five incomplete diaries from UKZN and six incomplete diaries from SMU that were excluded from analysis.

The 60 students were spread across 32 different sites, which included three PHC facilities and 24 sites in rural settings. As per the log diary guidelines, 26 students completed the log diaries in the second week of the IPC rotation, with the remainder in weeks 3, 4 and 6, respectively.

Time spent on each activity

Fig. 2 shows the proportion of student time spent on the five categories on the log diary form. The clinical activities at the DTPs ranged from 29.6% at Wits to 46.0% at WSU. Clinical activities included assisting in theatre, performing medical procedures and ward rounds. The students indicated that the majority of clinical activities were supervised, ranging from 88.2% at UKZN to 99.5% at WSU. Medical doctors supervised the clinical activities in the majority (85.9%) of instances, although other categories of health professionals also assisted with supervision.

Teaching time included attending a seminar/ meeting, teaching by a preceptor, teaching by other staff, contact with main campus, self-directed learning, and reading or study. Time spent on teaching ranged from 19.4% at WSU to 31.7% at Wits. Students recorded low amounts of time on skill acquisition. Similarly, students recorded low amounts of time spent in the community, ranging

from no time at SMU to 7.6% at UKZN.

Fig. 2 shows that at all four universities, students indicated that they spent similar proportions of time on activities of daily living, namely travelling, waiting, cooking, eating or shopping.

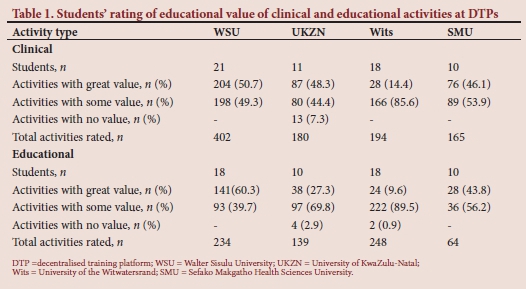

Perceived educational value

Notwithstanding clear guidelines on rating of the educational value of the various activities during their IPC rotation, the majority of the students rated the clinical and educational activities. In light of the missing data on skill and/or community activities, Table 1 only focuses on their rating of clinical and educational activities.

Table 1 shows that there were variations in the students' ratings of the value of the clinical activities. Across the four universities, UKZN was the only university where students rated 6.1% of the clinical activities to be of no value. Students' rating of clinical activities of great value ranged from a low of 14.4% at Wits, to a high of 50.7% at WSU.

In terms of educational activities, four students at UKZN (2.9%) and two at Wits (1%) rated these activities as having no value. Their rating of educational activities of great value ranged from a low of 9.7% at Wits, to a high of 60.3% at WSU.

Discussion

This study used log diaries with a voluntary group of final-year medical students to measure the proportion of time spent on each of five pre-determined categories of activities at the DTPs of four SA universities.

The study found that there were variations in the time spent on clinical activities, from 29.6% at Wits to 46% at WSU. We could not find similar studies focusing on medical student activities in other low- and middle-income settings. Although not directly comparable, Worley et al[16]found that patient contact (i.e. clinical activities) in Canada was higher when students were based at community sites than when students were based at secondary or tertiary hospitals. Encouragingly, the participating students reported adequate supervision of the clinical activities. Mubuuke et al.[23] have highlighted the importance of adequate supervision to the professional growth of undergraduate medical students.

Across the four universities, the majority of students reported that the clinical activities were of some or high value. At WSU, slightly more than half of students (50.7%) rated the clinical activities as of high value, similar to the ratings of students at SMU (46.1%) and UKZN (48%). In contrast, only 14.4% of the Wits students rated the clinical activities as of high value. A 2019 Wits study that examined final-year medical students' ratings of service-learning activities during an IPC block found that students reported positively on the educational value of the majority of

clinical activities.[19] However, the 2019 study used a different methodology to the present study, and this might account for the differences in findings. The higher student ratings at the three universities compared with Wits could be due to a more established clinical focus in the programme offered at Wits. As our study was conducted among a voluntary group of students at each of the four universities, further research is needed to determine whether there are significant differences across different universities, and the factors that influence these differences.

In this study, students indicated that they spent between 19.5% (WSU) and 31.7% (Wits) of their time on teaching activities at the DTPs. The teaching time included self-directed learning, which would be expected of final-year medical students, as they are on the cusp of entering the medical profession. The variations in the time spent on educational activities across the four universities might be a reflection of the actual DTPs. Our study could not determine the proportion of time spent on self-directed learning. However, a University of Pretoria study[24] among fifth-year medical students found that these students reported high amounts of time on self-directed learning, which led to a review of the assumptions about the importance of formal teaching. The majority of students in the present study rated the educational activities as of high or some value. Similar to the rating of clinical activities, a minority of Wits students (9.7%) rated the educational activities as of high value, compared with the majority at WSU (60.3%). Further research is needed to elicit the reasons for these inter-student and inter-university variations.

Students indicated that they spent very little time on practising or learning new skills. These skills include clinical, communication, decision-making, problem-solving and advocacy skills. The small proportion of time spent on such skills might be because of the emphasis placed on clinical skills training in the years leading up to the final year. A study[25] among students from the Ukwanda Rural Clinical School at Stellenbosch University identified improved confidence in their clinical skills and decision-making skills linked to their placement at the rural DTPs. The low proportion of time spent on skills might be a function of the week in which the diary was completed, the lack of opportunities available to the students, and/or the characteristics of the DTP. Nonetheless, it is a missed learning opportunity that students were not able to learn or practise a range of skills, including advocacy skills, at the DTPs. Advocacy is an essential undergraduate health professional competency in the health system context of working in rural and other under-served areas in SA,[21] and addressing the shortages of health personnel in rural areas.[25,27]

At SMU, students recorded that they spent no time on community activities, which include home visits and health promotion activities. Similarly, at WSU, students recorded that they spent less than 1% of their time on community activities, while Wits and UKZN students recorded that they spent 6.8% and 7% of their time, respectively, on community activities. This is of great concern, as the transformation potential of DTPs lies in immersion and exposure to communities, developing relationships with communities, learning about the social determinants of health, encouraging students to return to rural and underserved areas and to have a greater commitment to social accountability. [23,28-30]

Further research is needed to determine whether and why so little time was reportedly spent on PHC and community-based activities during the IPC rotation. Across all four universities, students recorded that they spent almost one-third of their time on activities of daily living. While this might reflect the nature of the DTPs, the findings suggest that there is potential to reorient the IPC rotation toward PHC and community-based activities.

Study limitations and strengths

Despite extensive efforts to achieve a representative group of final-year medical students at each university, the study is limited by the volunteer sample of 60 final-year medical students. At both SMU and UKZN, student participation was affected by the prolonged protests during 2018. These student volunteers who completed the log diaries are likely to differ from other students. Hence, the study findings are not generalisable to other final-year medical students. Notwithstanding careful guidelines for data entry, and regular follow-up with students, the missing information is a major limitation, especially in terms of gauging the educational value of the few reported community activities.

Nonetheless, there are several strengths to the study. The methodology of log diaries is innovative in capturing the activities and time spent at DTPs. The method allows for accurate recall of activities and ensures confidentiality and anonymity of participants. The log diary entries have generated new knowledge on the activities of medical students during the IPC rotation, such as the bias towards clinical activities and a relative absence of community exposure or immersion. This knowledge is important because medical doctor shortages in PHC and in rural and underserved areas remain acute yet are critical to overcome to achieve UHC and the goals of the proposed national health insurance system in SA.[31]

The lessons for future log diary studies are careful preparation, extensive consultation with and orientation of students prior to data collection, and possible daily submission of completed log diaries to pick up missing data at an early stage. Direct entry using mobile phone technology should also be explored.

Conclusion

This log diary study set out to quantify how final-year medical students spent their time during the IPC rotation at a DTP, and to determine student perceptions of the educational value of the various activities. Students reported that they spent a sizeable proportion of their time on clinical activities, while reported time spent on community-based activities was negligible. The bias toward clinical activities was also shown by students' completed ratings of the educational value of these activities, while the few community-based activities were left unrated. The policy implication of the study findings is that the transformation potential of DTPs in undergraduate medical education will only be realised when there is prioritisation of PHC and community-based activities.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We acknowledge the contributions of all the study participants, and Dr Duane Blaauw and Dr Janine White for the assistance with preliminary data analysis and the helpful discussion regarding the reporting measures.

Author contributions. AD - conceptualisation of study, protocol development, data collection, data analysis and interpretation and writing of article; LCR -supervisor for the study and contributed to conceptualisation, development, analysis and interpretation, as well as critical evaluation and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding. This research was partially supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Centre and the University of the Witwatersrand and funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No. B 8606. R02), Sida (Grant No. 54100113), the DELTAS Africa Initiative (Grant No. 107768/Z/15/Z) and Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)'s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa's Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (UK) and the UK government. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Fellow. LCR holds a South African Research Chair, funded by the National Research Foundation. AD held a Thuthuka grant, funded by the National Research Foundation for 2017-2019.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: WHO, 2016. [ Links ]

2. De Villiers MR, Blitz J, Couper I, et al. Decentralised training for medical students: Towards a South African consensus. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2017;9(1): a1449. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1449 [ Links ]

3. Academy of Science of South Africa. Reconceptualising health professions education in South Africa: Consensus study report. Pretoria: ASSAf, 2018. [ Links ]

4. Gaede B. Decentralised clinical training of health professionals will expand the training platform and enhance the competencies of graduates. S Afr Med J 2018;108(6):451-452. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.2018.v108i6.13214 [ Links ]

5. Van Schalkwyk S, Blitz J, Couper I, et al Consequences, conditions and caveats: A qualitative exploration of the influence of undergraduate health professions students at distributed clinical training sites. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:311. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1412-y [ Links ]

6. De Villiers M, van Schalkwyk S, Blitz J, et al. Decentralised training for medical students: A scoping review. BMC Med Educ 2017;17:196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1050-9 [ Links ]

7. Mlambo M, Dreyer A, Dube R, et al. Transformation of medical education through Decentralised Training Platforms: A scoping review. Rural Remote Health 2018;18:4337. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4337 [ Links ]

8. Alderson T, Oswald N. Clinical experience of medical students in primary care: Use of an electronic log in monitoring experience and in guiding education in the Cambridge Community Based Clinical Course. Med Educ 1999;33(6):429-433. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00336.x [ Links ]

9. Hannay DR. Student experience in family medicine at McMaster and Glasgow Universities. Med Educ 1980;14(3):204-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1980.tb02255.x [ Links ]

10. Cullen W Langton D, Kelly Y, et al. Undergraduate medical students' experience in general practice. Irish J Med Sci 2004;173:30. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02914521 [ Links ]

11. Boendermaker PM, Ket P, Düsman H, et al What influences the quality of educational encounters between trainer and trainee in vocational training for general practice? Med Teach 2002;24(5):540-543. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159021000012595 [ Links ]

12. Munro JG. Computer analysis of the student log diary: An aid in the teaching of general practice and family medicine. Medical Educ 1984;18:75-79. [ Links ]

13. Murray E, Alderman P, Coppola W, et al. What do students actually do on an internal medicine clerkship? A log diary study. Med Educ 2001;35(12):1101-1107. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01053.x [ Links ]

14. Rattner SL, Louis DZ, Rabinowitz C, et al. Documenting and comparing medical students' clinical experiences. JAMA 2001;286(9):1035-1040. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.9.1035 [ Links ]

15. Schamroth AJ, Haines AP, Gallivan S. Medical student experience of London general practice teaching attachments. Med Educ 1990;24(4):354-358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1990.tb02451.x [ Links ]

16. Worley P, Prideaux D, Strasser RP, et al. What do medical students actually do on clinical rotations? Med Teach 2004;26:594-598. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590412331285397 [ Links ]

17. Frambach JM, Manuel BAF, Fumo AMT, et al. Students' and junior doctors' preparedness for the reality of practice in sub-Saharan Africa. Med Teach 2015;37(6):64-73. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00336.x [ Links ]

18. Wilson N, Bouhuijs P, Conradie H, et al. Perceived educational value and enjoyment of a rural clinical rotation for medical students. Rural Remote Health 2008;8:999. [ Links ]

19. Mapukata N, Mlambo M, Dube R. Final-year medical students' ratings of service-learning activities during an integrated primary care block. Afr J Health Prof Educ 2019;11(2):35-37. https://doi.org/10.7196%2FAJHPE.2019.v11i2.906 [ Links ]

20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [ Links ]

21. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Core curriculum on human rights, ethics and medical law for health care professionals. Pretoria: HPCSA, 2006. [ Links ]

22. Dreyer AR, Rispel LC. Context, types, and utilisation of decentralised training platforms in undergraduate medical education at four South African universities: Implications for universal health coverage. Cogent Educ 2021;8(1):1906493. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1906493 [ Links ]

23. Mubuuke A, Oria H, Dhabangi A, et al. An exploration of undergraduate medical students' satisfaction with faculty support supervision during community placements in Uganda. Rural Remote Health 2015;15:3591. [ Links ]

24. Cameron D, Wolvaardt L, Van Rooyen M, et al. Medical student participation in community based experiential learning reflections from first exposure to making the diagnosis. S Afr Fam Pract 2011;53:373-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2011.10874117 [ Links ]

25. Van Schalkwyk S, Bezuidenhout J, Conradie H, et al. Going rural: Driving change through a rural medical education innovation. Rural Remote Health 2014;14:2493. [ Links ]

26. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Core competencies for undergraduate students in clinical associate, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa. Pretoria: HPCSA, 2014. [ Links ]

27. Gumede DM, Taylor M, Kvalsvig JD. Engaging future healthcare professionals for rural health services in South Africa: Students, graduates and managers perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06178-w [ Links ]

28. Talib ZM, Van Schalkwyk SC, Baingana RK, et al. Investing in community-based education to improve the quality, quantity, and retention of physicians in three African countries. Educ Health 2013;26(2):109-114. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.120703 [ Links ]

29. Hughes BO, Moshabela M, Owen J, et al The relevance and role of homestays in medical education: A scoping study. Med Educ Online 2017;22:1320185. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2017.1320185 [ Links ]

30. Williams-Barnard CL, Sweatt AH, Harkness GA, et al. The clinical home community: A model for community-based education. Int Nurs Rev 2004;51(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2003.00215.x [ Links ]

31. National Department of Health. National Health Insurance Policy: Towards universal health coverage. Pretoria, Republic of South Africa: NDoH, 2017. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A Dreyer

abigail.dreyer@wits.ac.za

Accepted 2 July 2021