Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.13 no.4 Pretoria Dez. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2021.v13i4.1291

RESEARCH

Development of a feedback framework within a mentorship alliance using activity theory

A G MubuukeI; I G MunabiII; S N MbalindaIII; D KateeteIV; R B OpokaV; R N ChaloVI; S KiguliVII

IMRad, MSc HPE, PhD; School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

IIMSc, MSc HPE, PhD; School of Biomedical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

IIIMSc, PhD; School of Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

IVMSc, PhD; School of Biomedical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

VMMed, MSc HPE, PhD; School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

VIMPH, PhD; School of Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

VIIMMed, MSc HPE; School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Mentorship is useful in enhancing student learning experiences. The provision of feedback by faculty mentors is a central activity within a fruitful mentorship relationship. Therefore, effective feedback delivery by mentors is key to the development of successful mentorship relationships. Mentorship is a social interactive relationship between mentors and mentees. Therefore, activity theory, a sociocultural theory, has been applied in this study to develop a framework for feedback delivery within the mentorship educational alliance between mentors and mentees

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to explore experiences of students and faculty mentors regarding feedback in a mentorship relationship, and to develop a feedback delivery framework in a mentorship relationship underpinned by activity theory

METHODS: This was a mixed-method sequential study conducted at Makerere University College of Health Sciences using both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. The study involved undergraduate medical students and faculty mentors. Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires, focus group discussions and interviews. Descriptive statistics were used for quantitative data, while thematic analysis was used for qualitative data

RESULTS: Most students reported negative experiences with feedback received during the mentorship process. Of the total of 150, a significant number of students (n=60) reported receiving no feedback at all from their mentors. One hundred students reported that feedback received from mentors focused on only weaknesses, and 80 reported that the feedback was not timely. A total of 130 students reported that the feedback sessions were a one-way process, with limited involvement of mentees. The feedback also tended to focus on academics, with limited emphasis on psychosocial contextual aspects that may potentially influence student learning. The focus group discussions with students confirmed most of the quantitative findings. The interviews with faculty mentors led to the emergence of two key themes, namely: (i) limited understanding of feedback delivery during mentorship; and (ii) need for feedback guidelines for faculty mentors. Based on the findings of the mixed-method study as well as the theory guiding the study, a feedback framework for mentorship interactions has been suggested

CONCLUSION: While students generally reported low satisfaction with feedback received from mentors, faculty suggested the need to have feedback guidelines for mentors to frame their feedback during mentorship interactions. A feedback framework to guide mentorship interactions has therefore been suggested as a result of this study, guided by principles of activity theory

Mentorship has been defined as a developmental relationship in which a more experienced person assists a less experienced person to grow professionally and realise their maximum potential.[1,2] Literature emphasising the importance of mentorship in health professions education is fast emerging.[3-6] The common denominator in this literature speaks to the fact that mentorship should be part of the overall student learning experience. In a number of institutions, the closest relationship a student has with a faculty member is through supervision during clinical rotations, practical sessions, tutorials and conduction of a research project.[7,8] However, such supervision is not necessarily mentorship, and students may not accrue the real benefits of mentorship.[8] A mentor is an advisor, coach, counsellor, teacher, listener and facilitator, who pays attention to all facets of the learning process, including cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains of learning. The mentor should view completed tasks within the realm of broader professional growth, positive progression and holistic development of the learner, focusing on not only academic achievements, but also psychosocial accomplishments.[9] Any feedback given therefore needs to target all these developmental aspects of the learner/mentee.

It is important that faculty (mentor) and learners (mentees) recognise that there are natural phases in the mentorship relationship, so that they can think purposefully and communicate effectively on how to maximise the relationship benefit and navigate transitions. The phases have been defined by different names in the mentorship literature.[8-11] However, they eventually converge on a similar meaning. These stages include: (i) initiation phase (creating rapport between mentor and mentee, setting targets); (ii) cultivation phase (maturation, and where mentee engages with mentor to reach set targets, involving performance reviews); (iii) separation phase (accomplishment of goals, evaluation of targets); and (iv) redefinition phase (moving on and closure, where mentee transitions from novice to expert). Through all mentorship phases, provision of feedback by the mentor is crucial.[9-13] Feedback is information provided to someone that identifies both strengths and weaknesses, aimed at attaining desired goals.[14] Effective feedback has been reported to facilitate the achievement of reflective, self-directed and life-long learning, and self-judging and self-regulated learning skills.[15] Mentoring is an interactive process through which faculty feedback can play a central role towards the acquisition of such skills.

At Makerere University College of Health Sciences in Uganda, where this study was conducted, students are randomly assigned mentors from their first year, and these are expected to interact with the students and nurture them during their development. The assigned mentors are academic faculty members at the institution. All faculty members are supposed to be mentors, and usually undergo some training in principles of mentorship. The training is usually a 1-day session that may occur once every academic year. Since the mentorship training occurs infrequently and is not periodically programmed throughout the year, some mentors have more skills and knowledge than others. Some junior mentors learn from more experienced mentors. In addition, students are engaged in an interactive talk on mentorship at the beginning of each academic year with the faculty. Therefore, the students may have some knowledge about mentorship.

The mentorship relationships have not been previously evaluated at the institution. In addition, there is limited published literature from the sub-Saharan African context that positions faculty-student mentorship relationships as a form of interactive educational alliance that involves learning via a community of practice between the faculty mentor, student mentee and learning environment. In this alliance, feedback is a key driver of the mentorship process. In the present study, we also applied principles of activity theory (AT), to develop a feedback framework to be used in the mentorship social learning interaction. Thus, AT provided a lens for the interpretation and synthesis of the findings in this study.

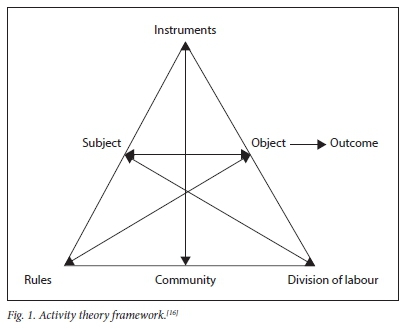

AT originated from the sociocultural tradition in Russian psychology, the key concept of which is the 'activity', which is an interaction between individuals (subjects) and the world (object).[16] The fulcrum of this theory is the 'activity'-a purposeful and transformative interaction between people. During the interaction, there are rules and roles, and tools to execute the activity and the targeted outcome to be achieved. Activity cannot thus be separated from the context in which it occurs. The AT framework is illustrated in Fig. 1.

According to the AT framework, any activity is organised into components that include: subjects (individuals being studied who are engaged in the activity, e.g. the mentors and mentees in a mentorship relationship); object (the raw materials or problem areas to which activity is directed, e.g. feedback) - the object of the activity could be either physical or a construct, and is always oriented towards achieving particular outcomes with the assistance of mediating tools or instruments; and instruments/ tools in the framework, which are mediation artefacts for executing the activity - instruments could be physical or mental artefacts. In a mentorship educational alliance, for example, an instrument for executing feedback delivery could be a feedback guide. All of these are geared towards a purpose to which members in a community of practice direct their activity (e.g. in a mentorship relationship, the activity of feedback delivery is directed towards addressing any gaps, and thus facilitating effective development of the mentee). Thus, it can be argued that the AT framework is applicable in a social learning environment such as a mentorship relationship. The relationship between the mentors/mentees and their environment is then considered through the component of community. Although AT has been applied in various settings, its application as an interpretive lens in mentorship relationships in health sciences education has been less widely reported. Thus, the purpose of this study was twofold: (i) to explore students' and mentors' experiences of feedback during mentorship relationships; and (ii) to utilise these experiences to develop a framework for feedback delivery during mentorship interactions underpinned by principles of AT.

Methods

Setting and design

This was a mixed-methods sequential study conducted at Makerere University College of Health Sciences between March and July 2019.

Participants

The study involved undergraduate medical students and faculty. Only faculty who had previously been mentors were included in the study. For the quantitative survey, simple random sampling was used to select 300 students. This was done by allocating all students codes, and randomly selecting 300 codes. These were the ones that were used. For the qualitative part of the study, two focus group discussions were conducted with the students, each group consisting of 8 participants. This translated into a total of 16 students who participated in the focus group discussions. Convenience sampling was utilised to select participants in the focus groups on a first-come, first-serve basis. Only students who had participated in the quantitative survey were eligible to participate in the focus group discussions. In addition, 10 individual interviews were conducted with faculty mentors. The faculty who participated in the individual interviews were selected using purposive convenience sampling. Faculty members who were available to give time to the study were selected.

Data collection

Quantitative data from students were collected using self-administered electronic questionnaires. The questionnaire captured the demographics of the students, an indication of their previous experience of mentorship and specific items regarding the students' experiences of feedback from their mentors during their mentorship relationships. The measure of positive experience of feedback received from faculty mentors was the indication of agreement with each item on the questionnaire. An item where students indicated either 'disagree' or 'neutral' was regarded as negative feedback experience during mentorship. Response frequencies were tallied. The questionnaire items were developed from a review of literature on student satisfaction with feedback within mentorship relationships. To provide a measure of face and content validity, the questionnaire was first piloted with 10 students. The major change made to the questionnaire was the wording of items that had technical educational terms such as outcomes that were not familiar to the respondents. Such terms were replaced with more basic words. Three weekly email reminders were sent to the students to complete the questionnaire. Qualitative data were collected using focus group discussions conducted with students, as well as individual interviews conducted with faculty mentors. One of the researchers moderated the discussions and interviews. Responses from the focus group discussions and interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed. Questions for the student focus groups and faculty interviews were open-ended and semi-structured. The questions were informed by findings from the quantitative survey and synthesis of previous literature. The qualitative aspect was aimed at further exploring the students' and faculty mentors' experiences of feedback within the faculty-student mentorship alliance.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., USA). This involved determining frequencies and percentages of responses to given items, as well as determining whether there were any significant differences in responses across the years of study the students were in. Thematic analysis was used for qualitative data using open coding. The coding was conducted manually by one of the researchers following an iterative process, and it commenced immediately after the first student focus group and first faculty mentor interview. The open coding involved identifying patterns of similar meaning from the participant responses. These were aggregated to form representative themes. Findings from the quantitative part of the study informed the questions developed for the qualitative part.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct this study was granted by the Research and Ethics Committee, School of Medicine, Makerere University (ref. no. REC REF 2019-007). Informed consent was also obtained from each study participant prior to conducting the interviews. Confidentiality of participants and their responses were also observed.

Results

Results were both quantitative and qualitative in nature.

Quantitative results

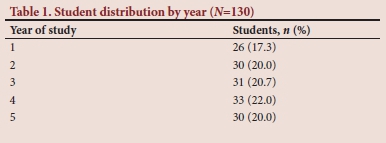

A total of 300 questionnaires were sent out to the sampled students electronically. Of these 300 sampled students, 72 were in year one, 70 were in year two, 62 were in year three, 50 were in year four and 46 were in year five. Of the 300 questionnaires sent out, 172 were returned, giving a response rate of 57.3%. Of the 172 returned questionnaires, 22 were excluded from further analysis because the students only partially completed the questionnaire, as they indicated that they had never previously participated in any mentorship relationship. This left 150 student questionnaires that were included in the final analysis. Therefore, the results presented were from the 150 students who fully completed the questionnaire. Of the 150 students included in the final analysis, 61.3% (n= 92) were male and 38.7% (n= 58) were female. The distribution of students by year of study is summarised in Table 1. The students who responded to the survey reflected similar numbers from each year of study. In order to assess student satisfaction with feedback received during their mentorship relationships, the students were asked to indicate whether they agreed with, disagreed with or remained neutral on key items. These findings are summarised in Table 2.

From Table 2, one can see that all students who completed the questionnaire reported knowing the meaning of mentorship, and reported having had a faculty mentor at one point in time during their studies. However, the majority of the students seemed not to fully understand the roles of mentors/mentees. Specifically, in relation to feedback during mentorship, the overall trend in findings generally indicates that students infrequently received feedback from mentors, and that the feedback was not very clear and mostly addressed students' weaknesses. In addition, the feedback from mentors mostly focused on academic matters, with less emphasis on psychosocial aspects of the students' experiences. More than three-quarters of the students reported that the feedback process was unidirectional and not interactive, with the mentor driving and dominating the process. Overall, the findings indicate low student satisfaction and negative experience with the feedback from their mentors. There were no significant differences noted across the different student years of study within the responses. Further insight into the meaning of the survey results was carried out using focus group discussions with students and interviews with faculty mentors.

Qualitative results

Two focus groups were conducted with 16 students about feedback from mentors. The students' experiences of the feedback from mentors are illustrated below.

Student experiences of mentor feedback

The student responses from the focus groups generally reflected what was observed from the survey results. For example, many responses emphasised the observation that feedback from mentors often addressed only weaknesses and not strengths, that feedback was infrequent and that little attention was paid to psychosocial aspects:

Although the mentors tried sometimes to give us feedback, they often pointed out only bad things ... this somehow demotivates us the students ... they should also point out what areas am doing well as my mentor.' 'My mentor used to point out mostly the negative aspects of what I was not doing well during our mentorship sessions . this was sometimes demotivating . I would have liked to hear more about what I was doing well also.'

'Mentorship would have been good if only our mentors also stressed those aspects that we the students are actually doing well . only pointing out the not so good things is not enough for us because we also want to know what is going on well both academically and socially ... since I believe that is what mentorship is all about.'

The aspect of feedback being infrequent during mentorship interactions can be seen through the following responses:

'Some of our mentors gave feedback about how we were learning.

However, they were rare and there was no formula of receiving this feedback. For me I only got feedback only once in the whole semester yet I would like to get such feedback more often.'

'I tried to meet my mentor as often as possible; however, this was not possible all the time. Therefore, the feedback I used to receive came only once in a while . I think there should be a schedule when we meet our mentors to give us feedback on our progression in medical school.'

'I think the frequency of the feedback meetings with our mentors needs to be streamlined. I agree we cannot meet mentors all the time, but some of us rarely got feedback that we desired yet that feedback is supposed to drive us to improve.'

The observation that mentor feedback focused heavily on academic issues is seen in the student responses below:

'As students, we have many issues affecting our studies. It may not be academic only, but social issues, stress, challenges. However, the mentors given to us most times only talk about academic matters . from what I know of a mentor, even they are supposed to guide us on how to go about some of these social challenges that may affect out studies.'

'Much as our mentors sometimes tried to give us feedback, however infrequent it was, this feedback the few times it was given to us tended to drill us on our academic progress. I do not remember my mentor for example having a talk about my social life, challenges and how I behaved in the mentorship relationship.'

The aspect of limited interaction between mentor and mentee during the feedback process also resonated through most responses, further emphasising the limited interaction observed in the questionnaire survey.

The following response reflects what was observed across most participants: 'I think our dear mentors should give us time to interact and participate in the feedback process, allowing us to give opinions and views regarding our studies. I think it would be interesting when we actively participate in the feedback process where we exchange ideas and opinions.'

Interviews with faculty mentors

In order to gain more understanding of the feedback process during mentorship, views were also sought from faculty mentors through individual interviews. Two key themes emerged from the faculty responses, namely: (i) limited understanding of feedback and mentorship; and (ii) need for feedback guidelines for mentors.

Limited understanding of feedback delivery during mentorship

The faculty interviewed in this study reported that they had limited training in feedback and the mentorship process. This may have influenced the manner in which they directed the feedback process during mentorship. The following responses reflected this observation:

'Feedback seems to be an important activity during mentorship. Although we may have some understanding of feedback principles and the mentorship process, probably we need more training on how first of all mentorship means and then how to give feedback during the mentorship process.'

'The fact that we as faculty are not trained on how to be mentors and how to give effective feedback most likely contributes to how our students experience the mentorship process. If mentors do not deliver well-balanced feedback, the students are likely to have negative attitude towards the whole process.'

From the responses above, it can be observed that mentors need training on how to drive the mentorship process, and then on how to give effective feedback for students to benefit from the mentorship relationship.

Need for feedback guidelines for faculty mentors

The other dominant theme that resonated through the faculty responses related to the need to have guidelines for giving feedback for faculty mentors. This can be seen through the following responses:

'Sometimes we do not know what to concentrate on when giving feedback to our mentored students. There are so many aspects to think about, but how do you prioritise? Probably we need some kind of guidance on what to consider when giving feedback to our students that we are mentoring.'

'Feedback is wide and there are so many aspects to consider depending on situation. As I mentor my students, how should I go about the feedback to give? Besides, we are different mentors and we need to give at the feedback that follows similar lines. Maybe we need some institutional guidance for feedback delivery during the mentorship interactions.'

The above responses demonstrate the need to have feedback guidelines for faculty mentors to be used during the mentorship interactions with students.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore student (mentee) and faculty (mentor) experiences of feedback delivery during mentorship, and to utilise these experiences to develop a framework for feedback delivery during these interactions. The developed framework is guided by principles of AT. The survey conducted with students demonstrated that they had mentors and reported some knowledge about mentorship; however, they were not satisfied with the feedback received from their mentors. From the present study, students demonstrated some knowledge about mentorship, probably owing to the fact that students are given orientation on mentorship at the beginning of every academic year, which may have increased their knowledge. They may have reported low satisfaction with mentor feedback because the feedback did not meet their expectations in terms of supporting their development.

From the reported literature, key principles of feedback delivery include timeliness, specificity, a balance between positive and negative feedback, and clarity.[14] From the student experiences reported, most of these aspects were not adequately met by mentors. This can partly be explained by mentor training that was inadequately focused on effective feedback delivery within a mentorship relationship, as evidenced by the responses from the mentors themselves. Feedback in mentorship relationships is key, and faculty mentors play a crucial role in this process. Therefore, training of mentors on how to effectively deliver feedback is important, an observation that has been previously reported.[12] The limited training in feedback delivery could perhaps also offer an explanation as to why some student mentees never received any feedback at all. However, it should be noted that training alone may not necessarily lead to improved feedback delivery during mentorship. Other factors, such as motivation and protected time for mentors, should also be considered.

As part of the leaning process, it has been reported that mentors' feedback to mentees should not focus only on academic progress, but also on other factors that may influence the holistic professional growth and development of the mentee.[9] Siddiqui[11] suggests that this may include provision of feedback on psychosocial and contextual experiences that a mentee may be undergoing. In the present study, mentors seemed to place less emphasis on feedback that targeted issues outside the academic progress of the students. Previous studies have also reported similar tendencies among some mentors.[8,10] The reason for this is not clear cut. However, a plausible explanation speaks to the limited importance mentors may attach to sociocontextual and psychological factors that may influence student progress. Mentorship interactions do not occur in a vacuum, but are rather situated within a community of learning. This community of learning may have various interacting factors that can influence student growth. Addressing these factors through feedback by mentors should therefore not be ignored.

The fact that students in this study experienced limited feedback from mentors targeting psychosocial aspects other than academic progress calls for significant attention. This observation may point to the need to have guidelines on feedback delivery for mentors. Such guidelines could emphasise key domains that mentors should focus on when framing their feedback. Having guidelines for feedback delivery during mentorship interactions was also proposed by the mentors themselves. It has been reported that mentorship should be an interactive process between mentees and mentors, where each person has a defined role to play, with mutually agreed-upon targets to achieve.[3] This active interaction involves dialectical communication in the form of feedback between mentor and mentee, which ultimately differentiates mentorship from supervision.[13] In the present study, we therefore propose a framework that can perhaps improve feedback delivery during mentorship interactions in a community of learning between mentors and mentees. This framework, guided by principles of AT, can potentially deepen our understanding of mentorship interactions and how well-framed feedback can play a role in enhancing these mentorship interactions in order to achieve the desired learning outcomes.

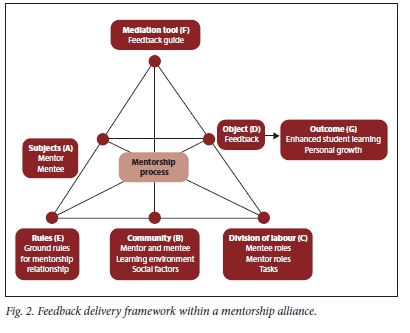

Framework for feedback delivery during mentorship interactions

Utilising findings from this study, a framework for feedback delivery in a mentorship relationship has been developed. The framework, based on AT, is illustrated in Fig. 2. This framework moves beyond merely training mentors in feedback delivery, and considers mentorship as a reciprocal process between the mentor and mentee in which each has a role within a community of practice. AT is useful in studying human interactions in a social group. Mentor and mentee interactions through feedback represent a social learning group, and thus principles of AT are key in such a community of learning. The fulcrum of this theory is an activity through which human interactions occur. In this study, the activity should be regarded as the feedback delivery process during mentorship interactions. Such an activity takes place within a community, organised into components that include: subjects; object; tools; rules; community; division of labour; and outcomes, key elements of AT. The components illustrated in the framework are dialectic in nature, interacting with each other within one system to influence the feedback delivery process. Therefore, there exist multiple mediating dialectical relationships within a complex integrated mentorship activity system. Subjects (A in Fig. 2) refer to the players in the mentorship interaction (i.e. the mentor and mentee). The mentor delivers feedback, and the mentee is the recipient of that feedback. The mentor and mentee thus form a team that actively engages with the feedback in an interactive manner. This team subsequently becomes a community of learning with a common understanding of their goals. Formation of this social community of learning is another key component of the activity framework (B in Fig 2).

Both mentors and mentees should have specific roles in the mentorship relationship that translate into a division of labour (C in Fig. 2) along with key ground rules that should be followed by both mentor and mentee (E in Fig. 2). To contextualise this to the mentorship process, tasks for both mentor and mentee need to be clarified, and feedback should focus on these tasks. In the context of this study, the object (D in Fig. 2) is the feedback itself, which should interactively occur between the mentor and mentee. This feedback plays a key role in the mentorship alliance as it provides the pathway towards achieving the targeted outcome of the mentorship relationship, which is enhanced student learning, and professional and personal growth of the mentee (G in Fig. 2). However, according to AT, a mediating tool is crucial to drive the feedback process within the mentorship alliance. Such a mediating tool can be in the form of a feedback guide (F in Fig. 2). The need for a feedback guide also strongly resonated throughout this study. Thus, from this study, we propose a feedback guide (mediating tool) for mentors that can potentially drive mentorship interactions in the desired direction. This feedback guide is crucial within the mentorship activity framework.

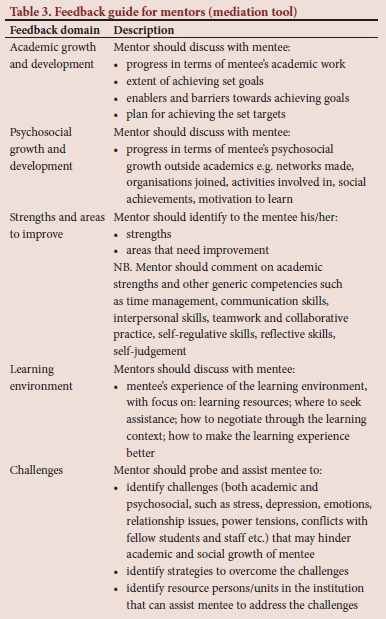

The feedback delivery guide for mentors: A mediation tool from the AT framework

The feedback delivery guide is summarised in Table 3. This guide is aimed at acting as a mediating tool for mentors during feedback delivery, and at ensuring that mentors frame their feedback to target holistic growth of mentees. The strength of the guide lies in its simplicity and highly structured nature. Structuring the guide is likely to achieve two things: (i) it may be acceptable to faculty, and feasible to implement; and (ii) it could be an avenue through which mentees receive feedback across other domains beside academic progress. Though structured, the feedback guide should not be viewed as restrictive to mentors. The mentor should be free to deliver feedback on any other aspects (s)he deems necessary for the benefit of the mentee.

This study utilised the experiences of students (mentees) and faculty (mentors) to develop a framework for feedback delivery during mentorship interactions. The framework was further underpinned by principles of AT, a sociocultural theory that places mentorship and feedback delivery within the mentorship relationship as an activity between faculty mentors and student mentees. Application of AT in this context to develop a feedback delivery framework has been infrequently reported in health sciences education, a gap that this study has tried to address. Specifically, the emergence of a mediating tool in the form of a feedback guide for faculty mentors may have implications for mentorship practice in health sciences education. Therefore, these findings form a basis upon which future studies can be anchored.

Study limitations

This study was conducted in one institution, but social and academic contexts may differ across institutions, and therefore the findings may not be generalisable, a major limitation of the study. In addition, the model/ framework developed did not consider other areas of student support such as peer mentorship/feedback that could be vital, since this was not the focus of the study. This could be an area for further research focusing on peer mentorship.

Further research

The implementation of the feedback guide developed for mentors, and evaluation of its potential impact on the outcomes of mentorship interactions, are particularly encouraged. In addition, the AT framework developed from the study perhaps needs further interrogation, especially investigating the various factors that interact within the mentorship activity system, such as peer mentorship/feedback, which could potentially provide additional support for students.

Conclusion

The present study explored student and faculty experiences of feedback delivery within a mentorship alliance. Students were not satisfied with the feedback, and faculty pointed to the lack of feedback guidelines to use for mentors. An activity framework has been developed to aid more understanding of feedback delivery within the mentorship alliance, and specifically, a feedback guide for mentors has been developed as a mediating tool to potentially improve feedback delivery within the mentorship relationship.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We thank all the participants who took part in this study.

Author contributions. AGM: conceptualised the study and developed the idea, drafted the protocol, collected data, participated in analysis and wrote the initial draft; IGM: participated in analysis and refining of the manuscript; SNM: participated in data collection and refining of the draft manuscript; DK: refined the initial manuscript draft; RBO: participated in analysis and refining of the manuscript draft; RNC: participated in collecting data and reading the initial draft; SK: refined the initial idea and provided critical input during writing the article, in addition to proofreading the final version.

Funding. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Centre of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), US Department of State's Office of the US Global AIDS Co-ordinator and Health Diplomacy (S/GAC), and President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) under award number 1R25TW011213. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Bhatia A, Navjeevan S, Dhaliwal U. Mentoring for first year medical students: Humanising medical education. Indian J Med Ethics 2013;10(2):100-103. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2013.030 [ Links ]

2. Dalgaty F, Guthrie G, Walker H, Stirling K. The value of mentorship in medical education. Clin Teach 2017;14(2):124-128. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12510 [ Links ]

3. Faucett EA, McCrary HC, Milinic T, Hassanzadeh T, Roward SG, Neumayer LA. The role of same-sex mentorship and organisational support in encouraging women to pursue surgery. Am J Surg 2017;214(4):640-644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.005 [ Links ]

4. Fricke TA, Lee MGY, Brink J, D'Udekem Y, Brizard CP, Konstantinov IE. Early mentoring of medical students and junior doctors on a path to academic cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thor Surg 2018;105(1):317-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.08.020 [ Links ]

5. Kostrubiak DE, Kwon M, Lee J, et al. Mentorship in radiology. Curr Prob Diag Rad 2017;46(5):385-390. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2017.02.008 [ Links ]

6. Nakanjako D, Byakika-Kibwika P, Kintu K, et al. Mentorship needs at academic institutions in resource-limited settings: A survey at Makerere University College of Health Sciences. BMC Med Educ 2011;11:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-53 [ Links ]

7. Keshavan MS, Tandon R. On mentoring and being mentored. Asian J Psychiatr 2015;16(August):84-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.08.005 [ Links ]

8. Meijs L, Zusterzeel R, Wellens HJ, Gorgels AP. The Maastricht-Duke bridge: An era of mentoring in clinical research - a model for mentoring in clinical research. A tribute to Dr. Galen Wagner. J Electrocardiol 2017;50(1):16-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2016.10.009 [ Links ]

9. Nimmons D, Giny S, Rosenthal J. Medical student mentoring programmes: Current insights. Adv Med Educ Pract 2019;10: 113-123. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S154974 [ Links ]

10. Schäfer M, Pander T, Pinilla S, Fischer MR, von der Borch P, Dimitriadis K. A prospective, randomised trial of different matching procedures for structured mentoring programmes in medical education. Med Teach 2016;38(9):921-929. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1132834 [ Links ]

11. Siddiqui S. Of mentors, apprenticeship, and role models: A lesson to relearn? Med Educ Online 2014;19(1):25428. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v19.25428 [ Links ]

12. Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach 2010;32(2):148-153. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903196995 [ Links ]

13. Singh S, Singh N, Dhaliwal U. Near-peer mentoring to complement faculty mentoring of first-year medical students in India. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2014;11:12. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.12 [ Links ]

14. Bowen L, Marshall M, Murdoch-Eaton D. Medical student perceptions of feedback and feedback behaviors within the context of the 'educational alliance'. Acad Med 2017;92(9):1303-1312. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001632 [ Links ]

15. Murdoch-Eaton, D, Bowen L. Feedback mapping - the curricular cornerstone of an educational alliance. Med Teach 2017;39(5):540-547. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1297892 [ Links ]

16. Engestrom Y. Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. PhD thesis. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit, 1987. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A G Mubuuke

gmubuuke@gmail.com

Accepted 14 July 2020