Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.13 no.2 Pretoria Jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2021.v13i2.1332

RESEARCH

Medical students using the technique of 55-word stories to reflect on a 6-week rotation during the integrated primary care block

A R DreyerI; M G MlamboII, III; N O MapukataIV

IBA, Adv Dip Adult Ed, MPH; Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIPhD; Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIPhD; Department of Institutional Research and Business Intelligence, Portfolio: Strategy, Risk and Advisory Service, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

IVMSc (Health Care Management), MSc (Med); School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Reflection and reflective practice are identified as a core competency for graduates in health professions education. Students are expected to be in a position to process experiences in a variety of ways through reflective learning. In doing so, they can explore the understanding of their actions and experiences, and the impact of these on themselves and others

OBJECTIVES: To draw on 5-weekly reflections by final-year medical students during the integrated primary care block placement. These reflections explore the learning that occurred during the rotation and the change in experiences during this period, and illustrate the use of reflection as a tool to support the development of professional practice

METHODS: This descriptive qualitative study analysed students' 55-word reflective stories during a 6-week preceptorship in either a rural or urban primary healthcare centre. The writing technique of short 55-word reflective stories was used to record student experiences. Inductive thematic analysis was conducted using MAXQDA software. This involved identifying the most commonly used words for each week through a word cloud, highlighting each week's most notable focus for learning to generate themes and sub-themes

RESULTS: Analysis of 127 logbook entries generated 464 stories on a range of experiences that had a significant impact on learning. Students' reflections in the first 2 weeks were linked to personal experiences and views about the block. In subsequent weeks, reflections focused on the individual responses of students to the learning experiences regarding the curriculum, patient care, ethics, professionalism and the health system

CONCLUSIONS: The reflections highlighted the key learning experiences of the medical students and illustrated how meaning is constructed from these experiences. The 55-word stories as a reflection tool have potential to support reflection for students, and provide valuable insight into medical students' learning journey during their clinical training

In recent years, there has been increasing interest for most medical education programmes to encourage reflection as a required competency. Programmes in higher education use student reflections as a measure to evaluate programmatic success.[1] The literature defines reflective learning as a mode of internally enquiring and questioning an issue of concern, caused by an experience.[2] This concern, which relates to the experience, creates and clarifies meaning for the student to learn from, which then translates into changes in their perspective. Reflective practice also helps to facilitate insights that might otherwise be missed. There is consensus among researchers that reflective practice must be demonstrated in observation of professional practice by students; similarly, in the education of students.[3,4]

Moon[5] lists many reasons for the practice of using journals and reflection as part of learning, such as fostering reflective and creative interaction; increasing active involvement in learning; and personal ownership of learning. She argues that enabling learners to understand their own learning process through reflection can be effective in aiding and reinforcing learning. Daudelin[6] suggests that reflection allows the opportunity for students to take a step back from an experience to ponder, carefully and persistently, its meaning to the self through the development of inferences.

This would suggest that learning is the creation of meaning from past or current events and can serve as a guide to future behaviour. These two important conditions for learning from experience, i.e. self-reflection and meaning-making, facilitate the formation of insights from past events and the application of these insights to future actions.[6]

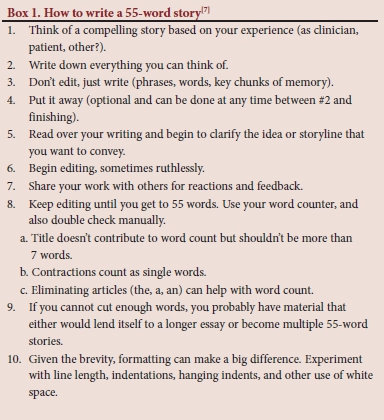

The Graduate Entry Medical Programme (GEMP) at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa (SA) was introduced in 2003 as a 4-year training medical programme that complements the traditional approach, leading to the completion of the MB BCh degree. Through this programme, students are exposed to aspects of community-based healthcare practice, including providing them with clinical skills necessary to function optimally in rural and urban community settings. The integrated primary care (IPC) block is a 6-week preceptorship in either a rural or urban primary healthcare centre, which may take place in a variety of settings, such as a healthcare centre or a clinic or district hospital, based in Gauteng or North West province.[3] As part of the IPC block, final-year medical students were asked to write short reflective stories of no more than 55 words on experiences that had the greatest impact at the end of each of week, until week 5 of their 6-weekly placement. To date, students continue to reflect using this tool for the block. Fifty-five-word stories make use of creative writing elements of prose.[7] The stories consist of 55 words and take on a poetic expression. This creative writing technique was first introduced in 1986 at an independent alternative weekly newspaper in California, USA, as part of a writing competition.

A 55-word story challenges one to pack in a lot in just a few words and has a structure, with 4 elements:[7]

• The setting is any place where the story is told. It can be the consultation room, the hospital or any space, including your mind.

• One or more characters can be the patient, self or even an inanimate

object.

• Conflict involves an event, which could be a fear, fight, conspiracy, reason or even silence.

• Resolution is a solution that concludes the story, giving the reader a good message or summary.

Box 1 details how Fogarty[7] proposes that a 55-word story should be written.

According to Fogarty, there is the gain of understanding of key moments for the writers and readers. There is also the gain of the healing arts in the shortness of the pieces, which adds to the impact of writing and reading.

Objectives

This article draws on 5-weekly reflections by final-year medical students during the IPC block placement. The reflections determine the student learning that occurred during the rotation and the change in experiences during this time, and illustrates the use of reflection as a tool to support the development of their professional practice.

Methods

Design

This descriptive qualitative study analysed 55-word reflective stories by medical students during a 6-week rotation. Students had to complete a section in their logbook, which required them to reflect on a weekly basis by writing 55-word reflective stories, recording their experiences of all learning activities, such as clinical skills.

Population and data collection

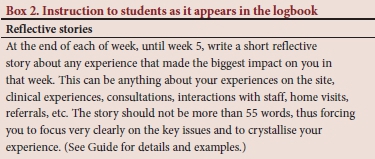

We used the data collected during the 2014 academic year as part of the IPC block placement. All final-year medical students participating in the IPC block placement were required to document 55-word reflective stories as part of the logbook. A total of 127 students submitted their reflective weekly stories for 5 weeks of the 6-week block. Box 2 shows the instruction as it appears in the logbook. The weekly reflective stories had no specific instruction regarding the details that should be included.

Data analysis

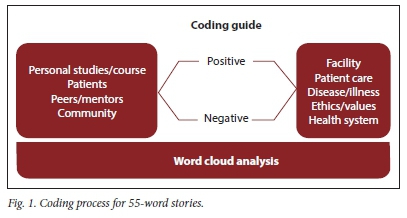

A total of 464 stories that were documented during one academic year (2014) were thematically coded and analysed using MAXQDA software version 11 (VERBI Software, Germany). Through an interactive inductive reasoning approach, the authors analysed each story to understand whether the reflective process influenced the learning experience or if it contributed to the development of professional practice of the students. The spelling and grammar of the stories were not subjected to an editing process. A word cloud was generated weekly to identify the most commonly used words in each week as an illustration of the most notable focus for learning. The most prominent words in the word cloud provided the themes to group the stories. Stories were then separated based on whether there was a positive or negative tone. All authors completed this process of coding to ensure intercoder reliability. Fig. 1 summarises the coding process. Direct quotations from students were used to support the identified themes.

Ethical approval

We received approval for the ongoing evaluation of the IPC block from the Wits Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. M1311162). The section on reflective stories that forms part of this study was not used as part of the overall assessment of students. No biographical details of the students were captured for the study. Data analysis was conducted independently of the assessment of the programme.

Results

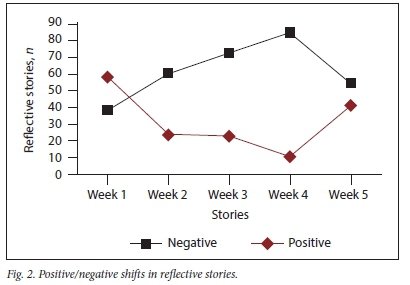

In total, 5 weekly reflections from 127 students were captured. Through consensus, the identified major themes oscillated between person- or patient-centred reflections, and influences on students' reflective practice. The coding process revealed two major shifts that had a positive and negative tone.

In week 1, the response rate was 75.6% (n=96). In week 2, there was a notable decline in the response rate at 66.1% (n=84). In the 2 follow-up weeks, the response rate was 74.8% for week 3 (n=95) and 74.8% for week 4 (n=94). During the last week of the reflections (week 5), the response rate was 74% (n=94). We hypothesise that the variation in the number of submitted reflections is attributed to the focus on placement objectives and adjustment of having to meet the demands of a clinical rotation. The maximum effort in week 3 is attributed to an adjustment to the setting, clarity on the objectives of the block and confidence that the placement would prepare students for the examination that is completed at the end of the rotation.

Positive/negative shifts in reflective stories

The positive/negative shifts during the 5 weeks are presented in Fig. 2. Interestingly, the positive shift illustrated the impact on learning in weeks 2 - 4, when students were clearly focused on their objectives and the learning that is provided in the placement.

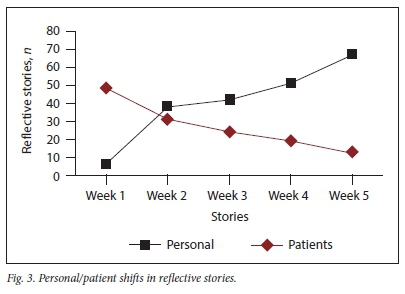

Personal/patient shifts in reflective stories

During the 5 weeks, there was a significant shift in the focus on the reflective stories. In week 1, the stories focused more on the personal experiences of adjusting to being in clinical settings outside of the academic training complex. From week 2, the stories were significantly more patient centred. A word cloud was generated by capturing words that suggested patient-focused reflections. Initially, students submitted a rather personalised viewpoint in their reflections. A shift became evident as students began to prioritise patients (Fig. 3).

Influences on students' reflective practice

The first dominant theme related to personal reflections had 4 sub-themes, i.e. studies/course, patients, peers/mentors and community.

The second dominant theme related to the facility; it had 5 sub-themes, i.e. facility, patient care, disease/illness, ethics/values and health system.

The narrative accounts provided by students on their commitment to their chosen profession often focused on personal factors, such as peer companionship and independence. Students indicated the importance of peer companionship - especially at the beginning of a block - as a determining factor for looking forward to providing service. The excerpt below shows the initial feelings of a student regarding the block, which later changed when peer companionship was realised:

'Krugersdorp, Muldersdrift. Sounds foreign. And strange. I got my Wits survival kits, so I hope to God I'll be fine. My initial thoughts on the IPC block. But oh, how wrong I was! Actually truly impressed and loving it.

Our group is really amasing, and it seems like I'm definitely going to enjoy this block.'

'Infectious smiles filling the waiting area. A pleasant change from grumpy, ill faces that we are usually exposed to. Working in the well-baby clinic provided a different sense of satisfaction. Providing immunisations and cheerful chatter left me feeling unusually positive, as opposed to the negativity often associated with many of our hospital cases.'

Peer companionship appeared to be strikingly important, as it allowed students to appreciate who they were, as they reported similar experiences together:

'Settling in to our new home for 5 weeks. I learn all about my new roommates. Sharing where we grew up, went to school and what drives us. Understanding the different reasons for studying medicine. Looking forward to experiencing the highs and lows together. What a good start to our 3rd block this year.'

A feeling of independence also influenced students' commitment to the practice of medicine. Although challenging at first, students enjoyed managing patients and providing the necessary treatment, while also assuming the role of a doctor. This point is echoed by one of the students:

'Beginning to love this block. Every day is an adventure for me filled with great learning experience. I feel like a qualified doctor in my own consultation room dispensing medication and writing sick notes. It is really exciting to be a part of the primary healthcare team.'

As the role of a doctor is assumed, the need to be familiar with the content becomes more evident:

'Little girl who knew her ABC, came in with red patches on her skin and knee, on history no trauma or injury, but her shins full of red, swollen mystery. What could the diagnosis possibly be? The mystery of her shins and knee. The next day it all came to me, erythema nodosum possibly.'

'You found your feet. Previously lost in seas of patients. A pre-programme due to patients. Accustoming to discipline, people you'll never meet. But now you start down a new road. Vast oceans with different tides. No one behind whom to hide. The undifferentiated territory is broad. But you use the gate keeper. It's only you.'

Having receptive staff made students appreciate their attachment to the site and, as such, developed their commitment to the profession. Students felt that having friendly staff who were willing to offer guidance when needed, greatly assisted their learning. To show appreciation towards the health facility staff, one of the students said:

'What impacted me the most this week was the friendliness and welcome reception we received from all the staff (nurses and doctors) in both the clinics and hospitals during our calls. Each person helped us achieve the most that we could, from every learning experience.'

The interest in medicine was also influenced by academic factors, such as having a significant learning experience, an opportunity to practise skills and an institutional reputation endorsement. A meaningful experience was seen as an important factor for influencing future professional practice. One student narrated how the amount of learning becomes nothing if there is no experience attached to it:

'I don't know anything! But you've spent 6 years at medical school? So? I don't know anything! Submandibular abscess, community-acquired pneumonia, infertility, urinary retention-ACUTE! So broad! So undefined! It could be anything! I could see anyone! Good! You've read it before, at least once! But, what's knowledge without experience? A challenge, of course!'

'I can see how this has the potential to be a beautiful and enriching experience. I will try in earnest to make it, even though living here in suboptimal conditions, will prove a considerable challenge. I am sure I can adapt. I will not lie, though, it has already begun to dampen my spirits.'

Significant learning experience was also evident with application of knowledge and skills learnt:

'Working in the clinics was initially challenging. The nurses, patients, diseases and problems that I encountered were unique. Even though I was equipped with the knowledge, I now needed to apply it in such a way that I had never done before. This was a new skill I had to learn. I needed to adjust.'

'My perceptions and reluctance to put effort (with all honesty) into my home visit as planned with sister Ellen was perpetually turned upside down in a matter of minutes. Seeing the harrowing nature of circumstances people live in first hand gave me a deeper appreciation for my life, and highlights the unfairness we so nearly share. Since this day no matter how much I thank my Lord, it can never be enough.'

The ability to practise skills learnt also influenced the interest students had in doing the work. The two stories below illustrate reflection on the skill. It appears that both stories relate to circumcision. In the first story, there

is an awareness of the role of after-hours calls in creating opportunities for learning though practice under supervision:

'As part of our weekend call we participated in medical male circumcision services. It was a wonderful learning experience. We were able to perfect our suturing skills. We were fortunate to be taught by a very student-oriented doctor. Who afforded us the opportunity to do circumcisions on patients unsupervised.'

In support of learning through practice, the second story illustrates mastery of skill:

'Circumcisions are easy, declared the doctor as he completed one in less than 5 minutes. Now it was my turn, with shacking hands I began taking 20 minutes for the first 'cos I lacked suturing experience. However, as I did more, I became faster - moral: practice makes perfect.'

Institutional reputation endorsement by clinical staff was another academic factor that had a positive influence on the medical students' approach to work. Students were resolute in demonstrating a commitment to the profession, as they felt that they had a responsibility to uplift the reputation of their academic institution:

'I am ... from ... university! So, you are from ... university! You guys have your ducks in a row. This was a common response I got from most of the doctors after introducing myself. It evoked feelings of inadequacy and also activated me to excel so I can live up to the "... university student" title.'

Discussion

The adoption of 55-word stories as one of the widely accepted journaling tools in family medicine, where reflective practice is just as critical as the practice of medicine itself,[8] was a novel experience for us. As a tool for professional growth and stimulating personal reflection on key training experiences, the combination of Fogarty's[7] approach and a word cloud generator became critical in guiding a process that appropriated the value of 55-word stories. Self-reflection encourages students to assume responsibility for their learning experience and also build a rapport between them and the site facilitator as they agree to disagree,[9] which is evident in the interplay of numerous factors influencing our students' 55-word stories. Furthermore, this reflection supports spending quality time with patients, becoming tuned to the patient experiences, and thus adapting to the environment.[10]

Reflective learning diaries play a role in mediating the limitations faced by medical students, and are an essential component of doctoring that is congruent with the experiences that were reflected by the students.[11,12] We propose that through this process of story-telling, the experiences of our students are validated as they connect with their patients emotionally in the process of providing healthcare. [13]

The difficult encounters that students refer to, as well as associated behaviours of feeling anxious, are similar to those reported by Shapiro et al.[14] In such instances, taking a moment to reflect is an opportunity to engage realistically on the range of clinical encounters as an affirming practice and a critical influence of one's professional development,[3] while also preparing for future practice.[2,15] The student narratives, while mostly focused on patient encounters, also provide insight to career affirmation that is realised,[10] professional relationships that are established and friendships that are formed at a moment in time.

Personal factors, such as having peer companionship and independence, influenced the students' commitment to the practice of medicine. This peer companionship and independence facilitated learning for students during their IPC block placement. These factors were further facilitated by student placement in small, intimate, clinical settings in groups of 3 - 4 students.[3] Such facilities created opportunities for students to learn from each other,[8] learn together and share tasks.[9] Similarly, in other studies, the student reflective accounts further revealed that managing patients holistically empowered them to build confidence and contribute to role identification for themselves as future healthcare providers.[3,6] A study conducted in a similar setting found that students felt more confident through experiential learning.[8] Our study found that the students' dedication and passion for work were highly motivated by site factors, such as having receptive staff and good teachers, who they could look up to as role models.[3,8,10] Academic factors were also shown to have an influence on their eagerness to work with patients. Additionally, we found that knowledge alone does not translate into experience. Through their 55-word reflective stories, experience was seen as an important factor to enable students to practise what they knew.[8] The narrative that the students presented through their reflections is informed by a setting that is different to the mainstream academic training complex with which they are familiar. The uncertainty that comes with managing difficult encounters, their professional skills (which may be inadequate for the setting) or issues related to patient experiences also influence the students' reflections.

Conclusions

Interest in reflection is based on the assumption that its value is linked to helping professionals to learn about and improve their practices.'151 All our students' stories speak to their professional development. The stories demonstrate a mode of internal inquiry that is consistent with reflective learning. More research is needed to explore how this feedback can be utilised to inform the design and planning of such activities to improve the future placements of students.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the co-ordinators of the block, Prof. Ian Couper and Dr Rainy Dube, and to the students who so eagerly engaged in sharing their 55-word stories. Acknowledgment and thanks are also due to the research interns, Alessandra Caldeira, Papike Makhuba, Mmapula Adams and Sine Madlala, for deciphering bad handwriting and capturing with such accuracy.

Author contributions. ARD: conceptualisation, data collection, thematic analysis, literature review, framework development, manuscript writing; MGM: literature review, thematic analysis, manuscript writing, editing; and NOM-S: literature review, manuscript writing, editing.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ 2009;4(4):595-621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [ Links ]

2. Finlay L. Reflecting on 'reflective practice. 2008. https://oro.open.ac.uk/68945/1/Finlay-%282008%29-Reflecting-on-reflective-practice-PBPL-paper-52.pdf (accessed 1 June 2021). [ Links ]

3. Mapukata NO, Dube R, Couper I, Mlambo M. Factors influencing choice of site for rural clinical placements by final year medical students in a South African university. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2017;9(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1226 [ Links ]

4. McAlpine L, Weston C. Reflection: Issues related to improving professors' teaching and students' learning. Instruct Sci 2000;28(5):363-385. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026583208230 [ Links ]

5. Moon JA. Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge, 1999. [ Links ]

6. Daudelin MW. Learning from experience through reflection. Organ Dynamics 1997;24(3):36-48. [ Links ]

7. Fogarty CT. Fifty-five word stories: ïmall jewels' for personal reflection and teaching. Fam Med 2010;42(6):400-402. [ Links ]

8. Cameron D, Wolvaardt L, van Rooyen M, Hugo J, Blitz J, Bergh A-M. Medical student participation in community-based experiential learning: Reflections from first exposure to making the diagnosis. S Afr Fam Pract 2011;53(4):373-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2011.10874117 [ Links ]

9. Tai JH-M, Haines TP, Canny BJ, Molloy EK. A study of medical students' peer learning on clinical placements: What they have taught themselves to do. J Peer Learn 2014;7(6):57-80. [ Links ]

10. Van Rooyen M. Using fourth-year medical students' reflections to propose strategies for primary care physicians, who host students in their practices, to optimise learning opportunities. S Afr Fam Pract 2010;54(6):513-517. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2012.10874285 [ Links ]

11. Nevalainen MK, Mantyranta T, Pitkala KH. Facing uncertainty as a medical student - a qualitative study of their reflective learning diaries and writings on specific themes during the first clinical year. Patient Educ Counsel 2010;78(2):218-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.011 [ Links ]

12. Charon R. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. J Am Med Assoc 2001386(15):1897-1902. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.15.1897 [ Links ]

13. Shapiro J, Bezzubova E, Koons R. Medical students learn to tell stories about their patients and themselves. AMA J Ethics 2011;13(7):466-470. [ Links ]

14. Shapiro J, Rakhra P, Wong A. The stories they tell: How third year medical students portray patients, family members, physicians, and themselves in difficult encounters. Med Teach 2016;38(10):1033-1040. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1147535 [ Links ]

15. Schön D. The Reflective Practitioner. New York: Basic Books, 1983. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A Dreyer

abigail.dreyer@wits.ac.za

Accepted 27 August 2020