Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.13 no.2 Pretoria Jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2021.v13i2.1191

RESEARCH

The workplace as a learning environment: Perceptions and experiences of undergraduate medical students at a contemporary medical training university in Uganda

Mike Nantamu KagawaI; Sarah KiguliII; Wilhelm Johannes SteinbergIII; Mpho P JamaIV

IMB ChB, MMed (Obstet Gynaecol), PhD; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

IIMB ChB, MMed (Paediatrics and Child Health), MHPE; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

IIIMB BCh, DTM&H, DPH, Dip Obst (SA), MFamMed, FCFP (SA); Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

IVBCur, PGDCH, MHE, PhD; Division Student Learning and Development, Office of the Dean, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: One of the most effective ways of translating medical theory into clinical practice is through workplace learning, because practice is learnt by practising. Undergraduate medical students at Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda, have workplace rotations at Mulago National Referral and Teaching Hospital (MNRTH), Kampala, for the purpose of learning clinical medicine

OBJECTIVES: To explore undergraduate medical students' perceptions and experiences regarding the suitability of MNRTH as a learning environment to produce competent health professionals who are ready to meet the demands of contemporary medical practice, research and training

METHODS: This was a cross-sectional study with a mixed-methods approach. Students' perceptions and experiences were assessed using the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM), as well as focus group discussions (FGDs). Data from DREEM were analysed as frequencies and means of scores of perceptions of the learning environment. FGD data were analysed using thematic analysis

RESULTS: The majority of students perceived the learning environment as having more positives than negatives. Among the positive aspects were unrestricted access to large numbers of patients and a wide case mix. Negative aspects included overcrowding due to too many students, and inadequate workplace affordances

CONCLUSIONS: The large numbers of patients, unrestricted access to patients and the wide case mix created authentic learning opportunities for students - they were exposed to a range of conditions that they are likely to encounter often once they qualify. The areas of concern identified in the study need to be addressed to optimise learning at the workplace for undergraduate medical students

Learning clinical medicine in the medical practice workplace is considered to be one of the most effective ways for students and lecturers to translate medical theory learnt in the classroom into clinical practice. The clinical workplace plays an important role in preparing students for future practice as physicians.[1] Advances in medical education have led to the establishment of skills laboratories as places for learning clinical skills using simulation-based medical education. However, realpatient encounters create authenticity in learning, because complaints are articulated better and physical signs are shown, with deeper and broader insight by real patients.[2]

Contemporary medical practice has evolved over time, with changes in health system expectations and clinical practice requirements, such as patient numbers and demographics and expectations of patients and employers.[3] While these changes are particularly obvious in developed countries, the advent of health-related technologies and increased litigation means this trend is rapidly catching up in developing countries, including Africa. All these changes have implications for training medical students to provide quality healthcare services on graduation. Concerns have been raised by employers, lecturers and regulators of medical graduates in Uganda and elsewhere that graduate competencies and population health

needs are mismatched.[4,5] For example, the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council (UMDPC) report of 2017/2018 describes cases of professional incompetence and unprofessionalism as some of the common offences handled by its ethics and disciplinary committee.[5] These offences may be an indication that the changes in health professions education have not kept pace with healthcare delivery expectations. Work and learning are interdependent, and understanding the perceptions and experiences of learners regarding the workplace as a learning environment may be an initial step in identifying the factors responsible for the mismatch between medical education and health system expectations.[6]

Studies assessing student perceptions of the learning environment using the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) questionnaire have been done in Nigeria, South Africa (SA), Turkey, Australia and the UK. The questionnaire comprises 50 items, divided into five separate domains that can be analysed individually.[7-10] No such study has ever been done in Uganda, thus creating an information gap and a need to evaluate the learning environment with a view to optimising learning in the workplace.

Undergraduate medical students at Makerere University College of Health Sciences (MakCHS), Kampala, Uganda, have placements at the workplace in Mulago National Referral and Teaching Hospital (MNRTH) for the purpose of learning clinical medicine as they progress from novices to proficient clinicians.

The purpose of the study was to explore undergraduate medical students' perceptions and experiences regarding the suitability of MNRTH as a learning environment that can produce competent health professionals who are ready to meet the demands of contemporary medical practice, research and training.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study design with a mixed-methods approach.

Setting

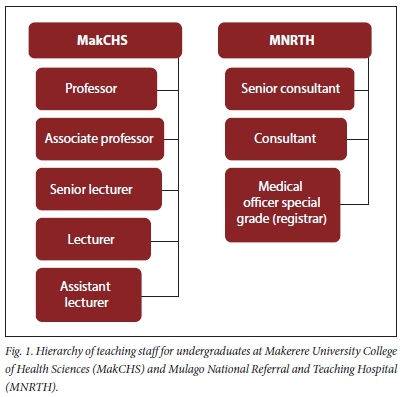

MNRTH has a bed capacity of 1 500 and is about 1.8 km (19 minutes' walk) from the main campus of MakCHS. MNRTH is the MakCHS teaching hospital for all clinical specialties (surgery (general surgery, orthopaedics, cardiothoracic surgery, neurosurgery), obstetrics and gynaecology, internal medicine, paediatrics and child health, ophthalmology, anaesthesia and critical care, and ear, nose and throat), save psychiatry, for which training takes place in Butabika Hospital, a specialised hospital ~9 km from MNRTH. Undergraduate medical students at MakCHS study for 5 years before graduation, and start their comprehensive clinical placements at the workplace in the fourth year. During these placements, groups of 30 - 40 students are allocated to each clinical specialty in MNRTH for workplace learning. Clinical placement in each speciality lasts 5 weeks during their fourth year, and 7 weeks during their fifth year. Lecturers of undergraduates include all specialist doctors (with at least a Master's degrees) from MNRTH and MakCHS (Fig. 1).

Prior to their comprehensive clinical placements, undergraduates are introduced to workplace learning during clinical exposure - from the first year. This is an observership, which is intended to assist students from an early stage of their medical training, so that they learn how to relate knowledge of the basic sciences to clinical conditions in the workplace.

Participants

All the study participants were undergraduate medical students (MB ChB) in their fourth and fifth years of study (N=258). Questionnaires were sent to 216 students who were rotating at MNRTH at the time of the study (42 medical students were excluded because they were in Butabika for their psychiatry placement); 170 completed questionnaires were returned and analysed.

Data collection

Quantitative data were collected using an adapted DREEM questionnaire. DREEM is a validated tool with 50 items for assessing an education environment, and has been tested for reliability and validity - though not in Uganda.[11] The adaptation focused mainly on language and context, e.g. teacher became lecturer, class became ward, and 'this year' became 'this course', so as to improve participants' understanding. The items in DREEM are scored using a Likert scale, offering the following options: strongly agree (S) - 4, agree (A) - 3, uncertain (U) - 2, disagree (D) - 1, strongly disagree (SD) - 0. Nine of the 50 items shown in italics (4, 8, 9, 17, 25, 35, 39, 48 and 50) (Table 1) are negative statements and are scored as strongly agree (S) - 0, agree (A) - 1, uncertain (U) - 2, disagree (D) - 3, strongly disagree (SD) - 4.

Participants for DREEM were selected by consecutive sampling.

Qualitative data were collected using a focus group discussion (FGD) guide with questions that were formulated from the literature and items in the DREEM tool that received the lowest scores, with additional questions being formulated as the FGDs progressed. The guide included questions on matters such as preparations prior to clinical placement, learner expectations and if they were met, positive and negative learning experiences in the workplace, learning opportunities and challenges and use of spare moments in the workplace. The FGDs were conducted by the principal investigator, who was assisted by an FGD expert.

The purpose of the FGDs was to explain and corroborate the findings from DREEM.[12] Participants for the FGDs were selected by purposive sampling; they could thus be comfortable with each other and be motivated to engage freely in the discussion and generate data based on the synergy of group interaction. Students in the fourth year were placed in separate groups from those in the fifth year. Each FGD comprised 8 - 10 medical students and lasted from 45 minutes to 1 hour. Efforts were made to ensure an equal number of male and female participants in each focus group. The FGDs were conducted shortly after DREEM had been completed, and students who had completed the DREEM questionnaire were eligible to participate in FGDs; they could, therefore, provide insights into the reasons underlying their DREEM responses. After obtaining consent, the discussions were recorded using an audio recorder. Additional notes were taken to record non-verbal interactions and to document the impact of group dynamics and exchanges of views.

Data analysis

Analysis of DREEM was done using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., USA), to determine the overall score and the scores for the five separate domains. Scores were interpreted according to the guidelines by McAleer and Roff.[7] The five domains are perceptions of learning (PoL), perceptions of teachers (PoT), academic self-perceptions (ASP), perceptions of atmosphere (PoA) and social self-perceptions (SSP). In addition, mean scores for individual items in DREEM were determined to pinpoint specific strengths and weaknesses in the learning environment. Items with mean scores of >3 indicated really positive points, between 2 and 3 were aspects that could be enhanced, and <2 were items that needed closer examination, as these indicated real problem areas.

Data analysis from the students' FGDs was done using ATLAS.ti software version 7 (ATLAS.ti, Germany) according to the seven stages of the framework method.[13,14] Audio recordings of the FGDs were transcribed into text, listened to and read several times as a way of becoming immersed in the data; then the data were exported to ATLAS.ti for analysis. Using an inductive approach, quotes were identified and open coding was done by 2 individuals, who later jointly developed a list of codes. These were used to code the rest of the transcripts, and the codes were then arranged into families that constitute the themes. The themes, which were developed deductively and inductively, are based on the FGD guide, as well as discoveries of unexpected perceptions and experiences of the students. The themes were used to describe and shed light on the attributes of the workplace as a learning environment.

Ethical approval

Before commencing with data collection, permission was obtained from the ethical committees of MakCHS (ref. no. 2015-125), MNRTH (ref. no. MREC 868), the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (ref. no. SS 3935), and the University of the Free State (ref. no. ECUFS 174/2015). Participation in the study was voluntary, as the consent forms approved by the Institutional Review Board stated. Anonymity of the study participants was ensured by using numbers instead of names on the DREEM questionnaire, while participants in the FDGs were assigned and referred to by letters - not by their real names. The FGDs were conducted in one of the offices on campus to ensure visual and auditory privacy. Confidentiality was ensured by storing the completed DREEM questionnaires in a locked drawer that was accessible to only the researcher and his team, while the audio recordings and transcripts were stored as password-protected files on a password-protected laptop belonging to the researcher.

Results

Quantitative results

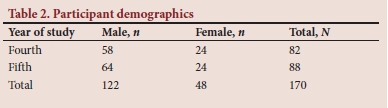

Completed questionnaires were returned by 170 students; 82 in the fourth year and 88 in the fifth year (Table 2), giving a response rate of 78%, which is similar to that of other studies.[8,9]

Overall perception of the learning environment

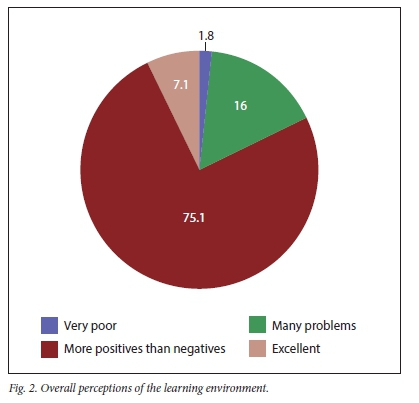

Of the 170 respondents, 12 (7.1%) perceived the learning environment as excellent, 127 (75%) perceived it as having more positives than negatives, 27 (16%) reported that there were many problems, while 3 (1.8%) rated it as very poor (Fig. 2).

Results of the domain sub-analysis are presented as percentages for the whole study population (Table 3), while mean scores for individual items are presented in Table 4.

A total of 114 students (67%) had more positive PoL, while 15 (8.8%) viewed teaching negatively (Table 2). Five of 12 items in this domain had mean scores >3.0, 6 items had means from 2.0 to 3.0, and 1 item scored <2 (Table 3). One hundred and eight students (63.9%) perceived the lecturers (PoT) as moving in the right direction, while 33 (19.5%) indicated that the lecturers were in need of further training (Table 2). Mean scores for this domain show only 1 item with a score >3.0 (Table 3). For ASP, 59 students (34.7%) were confident of performing well, while 85 (50%) reported a positive perception (Fig. 2). The mean scores for individual items indicate that, generally, students had a positive ASP, with 4 of the 8 items having mean scores >3.0 (Table 3). Regarding PoA, 106 students (62.4%) had a positive attitude, while 49 (28.8%) perceived the atmosphere as having many issues that needed attention (Table 2). The mean scores indicate none of the items scoring >3.0, while 3 had scores <2.0 (Table 3). In the domain of SSP, 79 students (46.5%) perceived the learning environment as not a nice place, while 74 (43.5%) reported that it was not too bad (Table 2). All items in this domain had mean scores <3.0 (Table 3), reflecting a social environment with issues.

Qualitative results

Three themes emerged from the results of the FGDs, i.e. learning opportunities, overcrowding and workplace affordances.

Learning opportunities

According to the students' perceptions, there were good learning opportunities at the workplace, because of large number of patients, unrestricted access to the patients and a wide case mix. There were also challenges, as illustrated by the following quotes:

'For Mulago as a teaching hospital, the patients are there with all sorts of diseases, so we get the exposure which is a bonus and they want you to attend to them so you can never say you don't have a patient.' - Fifth year 'About the working environment here, am very positive about it that there is opportunity to learn, because in Mulago, which is a national referral hospital, we get all kinds of patients and conditions, so there is a very big opportunity to learn.' - Fourth year

'I expected to gain practical skills in addition to enriching my knowledge but I have not yet realised all my expectations, OK, I have gained knowledge, but mostly the practical aspect is a bit lacking, it is still limited.' - Fifth year 'I know problem-based learning is supposed to be more self-driven; we do 80% of the reading and they give us a little of the 10% but then even this 10% they are not giving it; we have to hustle to get the clinical teaching.' - Fourth year

Overcrowding

The students reported that the wards as learning spaces were overcrowded by students, as illustrated in the following quotes:

'Now, for me, those clinicals, first of all we were so many, you had to be extremely vigorous as you fight to view and you have to stand. I think I wasn't so aggressive and I reached a point when I would just sit. When people are done, I just ask someone, "what did they say?" And you find one person heard half-way, another one heard another version and another one also heard another version.' - Fourth year 'You find that there are so many of us; senior house officers, fifth years, and you the fourth years; you are the underdog, you are the lowest in the food chain, and you sometimes have to stand somewhere far from the patient's bed because the whole place is packed, they are doing something and you can't see and you learn nothing.' - Fourth year

Workplace affordances

Workplace affordances are situational factors that invite and support learner participation, and participants had this to say:

'There are some [lecturers] who trash what you say, you know introducing something and then someone tells, "That is very wrong! Ooh my God you are so stupid, our generation of doctors was better, you want to kill our patients!"' - Fifth year

'I think some of these doctors have been employed because they excelled in school. Someone can excel academically but when they don't know how to teach, when they don't have the heart to teach so I think it is better for us to have somebody who can teach us whether they are excellent or not, than somebody who is so excellent but can't teach.' - Fourth year 'I think the first thing they should do is to first reorient the lecturers, the doctors or workers, on their duties besides seeing patients, they should be taught how to teach. They should train them every year like in seminars.' - Fifth year

Other contributors to workplace affordances, such as nurses, paramedics and laboratory personnel, were also not supportive, as illustrated by the following quotes:

'I think there is a problem with the nurses and yet there is a lot we can also learn from them. I realise that there is this attitude they have about medical students; I think they are not aware. If you ask for any help, they don't want to help. They tend to keep away everything you are supposed to use on the ward; the gauze, the vacutainers, the gloves, so you sort of have to beg all the time and yet they have this attitude that won't encourage you to go on.' - Fifth year

'Yes, because some of them are really very unfriendly, they are already biased, like I went to some clinic and the nurse said, "These medical students want to behave as if they are doctors." It is really our first day there and we do not know what to do, so how can we behave like doctors? Then I tried asking another one and she put me off and told me to wait for our doctors to teach us. So, for example, I might come and maybe there are no doctors, does that mean I cannot be taught? So, your day is gone, so it is not nice at all.' - Fourth year

Discussion

Overall, the majority of the participants (75.1%) viewed the learning environment as having more positives than negatives (Fig. 1). This finding is comparable with results obtained by studies with regard to the education environment of medical training schools in SA and Canada.[8,15] The results of the FDGs validated the positive assessment found by DREEM among the positive attributes of the workplace at MNRTH, i.e. unrestricted access to patients, large patient numbers and wide case mix. These attributes should apply to any learning environment if the goal is an authentic learning experience where students gain knowledge, skills and the right attitudes while experiencing professional practice first-hand during their transition from a student identity to that of a clinical practitioner.[16]

There were factors at the workplace that appeared to serve as barriers to learning. Among these factors that limited student participation in learning activities were overcrowding and inadequate workplace affordances. Participation in activities at the workplace is central to the acquisition of competence, as clinical medicine is learnt by practising, and an environment with adequate workplace affordances motivates students to participate in the activities according to their ability.[17] Innovative solutions to address overcrowding in the workplace, such as using satellite learning environments, are, therefore, required to provide sufficient opportunities for all students to participate in workplace activities.[18] In the absence of supported participation in patient care, acquisition of the necessary competence can be compromised, leading to students experiencing self-perceptions of academic inadequacy, which consequently lead to poor learning outcomes.[17]

Perceptions of learning

The students generally had positive PoL at the workplace, and teaching was highly regarded (Table 2). Similar findings are reported by a study done in India.[19] The large number of patients available, a wide case mix and students having easy access to patients are important for competence development, as the students are exposed to real-life experiences during workplace learning. Further analysis shows that 5 items in this domain had mean scores of >3.0, indicating really positive points. Six items, however, had mean scores between 2.0 and 3.0, implying areas that need close review (Table 3), and that students prefer a more focused approach to clinical teaching, better utilisation of clinic time, clearer learning objectives and greater participation during workplace learning.

Perceptions of teachers

While lecturers were mainly perceived as moving in the right direction and being knowledgeable, some were perceived as being in need of further training in clinical teaching (Table 2). This opinion was validated by the participants during the FGDs, when they said, 'the lecturers needed to be taught how to teach'. Many physicians are experts in their fields, but their communication-related attitudes and abilities are lacking, which can have a negative impact on students' competence development.[20] Among the attributes clinical lecturers are expected to have, such as interpersonal skills, ability to teach, professional skills and administrative skills, ability to teach was ranked highly by the medical students in one study.[21] Beyond content expertise, clinical lecturers should, therefore, have an all-round capability to diagnose patients based on the clinical findings, in addition to 'diagnosing' students by observing their skills, attitudes and knowledge expressed during the teacher-student encounter.[22] Clinical lecturers, therefore, need to be empowered to perform these tasks better, which could be achieved through focused faculty-development sessions.

Academic self-perceptions

A cumulative percentage (85%) of students expressed a positive ASP, implying that the majority were hopeful of performing well, as the workplace at MNRTH was supportive of undergraduate learning (Table 2). The medical school is essentially a community of high achievers, and ASP can be affected by actual individual achievement, or by comparison with peers. ASP reflects how students perceive themselves as fitting into the context of the learning environment,[23] which plays a very important role in ensuring the highest possible academic achievement and student satisfaction. When students perceive that the strategies they have used before suit them within the context of the learning environment, it gives them a sense of assurance in their ability to perform, they become more confident and they are encouraged to perform to their highest potential.[19] The small percentage (10%) of participants who perceived the workplace as having many negative aspects, and the 5% who reported feelings of total failure, represent a group of students whose expectations were not met during workplace learning; the attribute with the lowest mean score in this domain related to opportunities to practise at the workplace. Students with negative perceptions of the learning environment are likely to associate this environment with poor learning outcomes.[17] Similar findings are reported in an Indian study, whose authors recommend that future studies should explore the reasons behind the scores during FGDs.[19] To improve competence development during workplace learning, supported participation should be prioritised. There should be greater appreciation of content and situations in which content could be applied than of mere knowledge acquisition, which may be required mainly for passing tests.[20,24]

Perceptions of atmosphere

While most participants had positive perceptions of the learning atmosphere, close to one-third (29%) perceived the atmosphere as having several issues that need changing (Table 2). All the items in this domain had mean scores of <3.0, indicating a need to enhance the atmosphere. Three items that scored <2.0 indicate real problem areas that require closer scrutiny (Table 3). The participants identified a tense atmosphere during ward teaching, improper timetabling, and too much stress caused by work as areas that needed attention. Education stakeholders should, therefore, view the learning atmosphere as an ecosystem that is composed of lecturers, patients and students to contextualise the importance of the complex interaction between these entities for cognitive, behavioural and psychomotor applications during competence development.[23]

Social self-perceptions

The social climate in a teaching institution has important implications for the learning experience.[19] The SSP domain produced results that were quite different from those of the other domains, with an almost equal number of students perceiving the learning environment as 'not too bad' (43.5%) and as 'not a nice place' (46.5%). At the extremes, a greater percentage of participants perceived the learning environment as 'miserable socially' (8.8%) than those who judged it to be 'very good socially' (1.2%). Similar results were reported by studies in Nigeria and SA.'7,81 All items in this domain had mean scores <3.0, which is worrying, because these scores reflect a learning environment with major issues (Table 3). This domain returned items with the lowest mean scores throughout DREEM, e.g. places of convenience scored 1, and meals 0.38. This reflects problem areas that need to be examined closely, because these are basic needs on Maslow's hierarchy of needs.[25] Meals are an important part of the social environment, and unpleasant meals can be a source of stress and lead to poor academic performance. Studies have demonstrated that, although brain maturation occurs early in life, certain functions continue to develop into adulthood, and nutrition can play a role in the development of abstract thinking and problem-solving skills.'261 There is, therefore, a need to create a learning environment in which social amenities are available and interaction is promoted through good social networks among students and faculty. Doing so will minimise work stress and promote learning.

Study limitations

A limitation of this study was that only the perceptions of students were explored, excluding faculty involved in clinical teaching of undergraduates at this medical school. However, this limitation is mitigated by the use of validated data collection tools and triangulation with quantitative and qualitative methods, which provided corroboration of findings.

Conclusions

Overall, the majority of students perceived the learning environment as having more positives than negatives, which created authentic learning opportunities based on the availability of patients, a wide case mix, unrestricted access to patients and knowledgeable lecturers. The areas of concern included overcrowding and inadequate workplace affordances, improper approaches to clinical teaching, with few opportunities for supported participation, probably due to lecturers' inadequate clinical teaching skills, and a stressful learning atmosphere with inadequate social support networks.

Recommendations

Effective workplace learning at MNRTH requires that the positive attributes pointed out in this study are enhanced, while the negatives are addressed.

While lecturers were expected to provide background knowledge, for which they were rated highly, the transition from a student identity to that of a clinical practitioner requires that students are provided with opportunities by the lecturers for supported participation in clinical activities at the workplace. It therefore becomes imperative that educational stakeholders focus efforts on improving workplace learning by addressing factors that encourage students to appreciate content and situations in which it may be applied - more than gaining knowledge for the purpose of passing an examination.

Areas of further research

Because of the complexity of workplace learning, further research is needed to determine the perceptions of other stakeholders, such as lecturers and administrators, and possibly patients. Armed with information from all these stakeholders, any suggestions for improvement could be subjected to a Delphi study to generate recommendations for improving the workplace as a learning environment using an all-inclusive approach.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We would like to acknowledge the students who agreed to participate in the study, and the research assistants who assisted with data collection.

Author contributions. MNK contributed to the conceptualisation of the idea, the design of the study, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing; SK contributed to conceptualisation and concretisation of the idea, the design of the study and manuscript writing; HS contributed to conceptualisation and concretisation of the research idea, the design of the study and manuscript writing; and MPJ contributed to the conceptualisation and concretisation of the research idea, the design of the study and writing the manuscript.

Funding. Most of the funding for this work was from personal savings. Additional funding was obtained from two sources: (i) NURTURE (grant number D43TW010132) to attend some courses pertinent to this work; supported by the Office of the Director National Institutes of Health (OD), National Institute Of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Fogarty International Center (FIC), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD); and (ii) Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, US Department of State's Office of the US Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy (S/GAC), and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) (award number 1R25TW011213) for AJHPE page fees. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Sajjad M, Mahboob U. Improving workplace-based learning for undergraduate medical students. Pak J Med Sci 2015;31(5):1-3. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.315.7687 [ Links ]

2. Akaike M, Fukutomi M, Nagamune M, et al. Simulation-based medical education in clinical skills laboratory. J Med Invest 2012;59(1-2):28-35. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.59.28 [ Links ]

3. Weinberger S. The medical educator in the 21st century: A personal perspective. Transact Am Clin Climatolog Assoc 2009;120:239-248. [ Links ]

4. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376(9756):1923-1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61854-5 [ Links ]

5. Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council. Annual report. 2016/2017. https://www.umdpc.com/Resources/Brochures/ANNUAL%20REPORT%20FY%202016-2017.pdf (accessed 22 April 2021). [ Links ]

6. Le Clus MA. Informal learning in the workplace: A review ofthe literature. Austr J Adult Learn 2011;51(2):355-373. [ Links ]

7. McAleer S, Roff S. (2002). Part 3: A Practical Guide to Using the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). In: Genn JM, ed. AMEE Education Guide No. 23, Curriculum, Environment, Climate, Quality and Change in Medical Education: A Unifying Perspective. Dundee, UK: Association of Medical Education in Europe, 2002. [ Links ]

8. Schoeman S, Raphuting R, Sebakeng P, et al. Assessment of the education environment of senior medical students at the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2014;6(2):143-149. https://doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.397 [ Links ]

9. Tontuç HO. DREEM; dreams of the educational environment as its effect on education result of 11 medical faculties of Turkey. J Exp Clin Med 2010;27:104-108. https://doi.org/10.5835/jecm.omu.27.03.002 [ Links ]

10. Vaughan B, Carter A, Macfarlane C, et al. The DREEM, Part 1: Measurement of the educational environment in an osteopathy teaching program. BMC Med Educ 2014;14(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-99 [ Links ]

11. Koohpayehzadeh J, Hashemi A, Solatani Arabshahi K, et al. Assessing validity and reliability of Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2014;28:60. [ Links ]

12. Östlund U, Kidd L, Wengstöm Y, et al. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48(3):369-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.005 [ Links ]

13. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [ Links ]

14. Woods M, Paulus T, Atkins DP, et al. Advancing qualitative research using qualitative data analysis software (QDAS)? Reviewing potential versus practice in published studies using ATLAS.ti and NVivo, 1994 - 2013. Soc Sci Computer Rev 2015;34(5):597-617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315596311 [ Links ]

15. Veerapen K, McAleer S. Students' perception of the learning environment in a distributed medical programme. Med Educ 2010;15(1):5168-5177. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v15i0.5168 [ Links ]

16. Magnier K, Wang R, Dale VHM, et al. Enhancing clinical learning in the workplace: A qualitative study. Vet Rec 2011;169:682. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.100297 [ Links ]

17. Chen HC, ten Cate O, O'Sullivan P, et al. Students' goal orientations, perceptions of early clinical experiences and learning outcomes. Med Educ 2016;50(2):203-213. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12885 [ Links ]

18. Kibore MW, Daniels JA, Child MJ, et al. Kenyan medical student and consultant experiences in a pilot decentralised training program at the University of Nairobi. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2014;27(2):170-176. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.143778 [ Links ]

19. Pai PG, Menezes V, Srikanth, et al. Medical students' perception of their educational environment in Western Maharashtra in medical college using DREEM Scale. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8(1):103-107. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2014/5559.3944 [ Links ]

20. Pimmer C, Pachler N, Genewein U. Contextual dynamics in clinical workplaces: Learning from doctor-doctor consultations. Med Educ 2013;47(5):463-475. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12130 [ Links ]

21. Kiani Q, Umar S, Iqbal M. What do medical students expect in a teacher? Clin Teach 2014;11(3):203-208. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12109 [ Links ]

22. Salam A, Siraj HH, Mohamad N, et al. Bedside teaching in undergraduate medical education: Issues, strategies, and new models for better preparation of new generation doctors. Iran J Med Sci 2011;36(1):1-6. [ Links ]

23. Patel RS, Tarrant C, Bonas S, et al. Medical students' personal experience of high-stakes failure: Case studies using interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMC Med Educ 2015;15(86). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0371-9 [ Links ]

24. Barab SA, Roth W-M. Curriculum-based ecosystems: Supporting knowing from an ecological perspective. Educ Res 2006;35(5):3-13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x035005003 [ Links ]

25. Kenrick DT, Griskevicius V, Neuberg SL, et al. Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspect Psychol Sci 2010;5(3):292-314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610369469 [ Links ]

26. Correa-Burrows P, Burrows R, Blanco E, et al. Nutritional quality of diet and academic performance in Chilean students. Bull World Health Organ 2016;94(3):185-192. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.15.161315 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M N Kagawa

kagawanm@yahoo.com

Accepted 29 July 2020