Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.13 no.2 Pretoria Jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2021.v13i2.1257

RESEARCH

Curriculum mapping: A tool to align competencies in a dental curriculum

R MaartI; R Z AdamII; J FrantzIII

IBChD, MPhil; Department of Prosthetic Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

IIPhD; Department of Restorative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIPhD; Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: In response to the adoption of the African Medical Education Directives for Specialists (AfriMEDS) competency framework by the Health Professions Council of South Africa, all dental schools in the country were required to incorporate and implement the core competencies described in AfriMEDS in the undergraduate curricula

OBJECTIVES: To describe curriculum mapping as a tool to demonstrate the alignment of an undergraduate dental curriculum with a competency framework, such as AfriMEDS, in preparation for accreditation and curriculum review

METHODS: All the module descriptors (n=59) from the first to fifth year of study were included, and outcomes were mapped against the AfriMEDS competency framework. The presence of AfriMEDS core competencies (healthcare practitioner, communicator, collaborator, health advocate, leader and manager, scholar, professional) were located (if present) within the module learning outcomes. AfriMEDS core competencies were quantified and illustrated in the form of a curriculum map

RESULTS: Healthcare practitioner, health advocate and communicator were present across all 5 years of the undergraduate dental curriculum, while healthcare practitioner was present in 46 modules, health advocate in 8 modules and communicator in 13 modules. Competencies related to collaborator were present in the first, third and fifth year in 7 modules. Leader and manager competencies were present in the fifth year in 1 module. Professional competencies were present in the second and fifth year in 3 modules. Competencies related to scholar were present in the first, third, fourth and fifth year in 8 modules

CONCLUSIONS: From the results, it was highlighted that all AfriMEDS competencies were present in the University of the Western Cape (UWC) dental programme. Curriculum mapping identified gaps in or areas of development for the AfriMEDS competencies in the UWC dental curriculum. Curriculum mapping can be recommended as a valuable tool for curriculum development

Accreditation visits are 'high stake' processes that have a tendency to place additional pressure and workload on a faculty. For accreditation, medical and dental schools need to provide evidence that their graduates are trained according to the requirements of the accreditation bodies and are therefore able to service the needs of patients. In preparation for these accreditation processes, guidelines are provided for the schools by the accreditation bodies to ensure transparency and fairness.

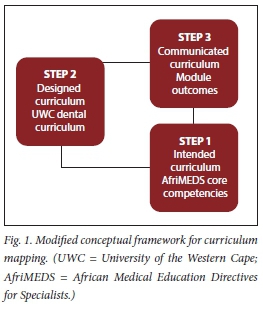

The Medical and Dental Professions Board of the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA), in collaboration with training institutions and the South African Committee of Medical and Dental Deans, adapted the core competency framework of the Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) to inform medical and dental curricula in South Africa (SA).[1] This adapted version of the CanMEDS framework is the competency framework of the African Medical Education Directives for Specialists (AfriMEDS) (Fig. 1). The AfriMEDS framework guides the accreditation process of all medical and dental schools in SA.[2]

Because of the adoption of the AfriMEDS competency framework by the HPCSA, all dental schools in SA are required to incorporate and implement the core competencies described by AfriMEDS in undergraduate curricula. Each dental school has autonomy in the strategies for implementation of these core competencies in its undergraduate dental curriculum. A self-evaluation questionnaire is used in the accreditation process of the undergraduate curriculum to elicit information about the implementation and translation of the AfriMEDS core competencies.

From a previous undergraduate dental accreditation process at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), SA, it was found that the core competencies were not clearly or consistently described and the implementation thereof was not evident. Furthermore, the translation of the AfriMEDS core competencies throughout the undergraduate dental curriculum was not explicit. Consequently, the completion of the self-evaluation questionnaire was challenging, thus highlighting the need for the development of clear guidelines regarding the implementation and translation of AfriMEDS core competencies in the undergraduate curriculum.

Globally, schools have been increasingly obliged to maintain a curriculum map as part of their ongoing accreditation reporting.[3] National competency-based frameworks and consented outcomes serve as curricular guidelines in medical and healthcare education.[4] Harden[5] introduced the concept of curriculum mapping and asserted that 'the real genius of mapping is to give a broad picture of the taught curriculum' or 'authentic picture'.[3] Mapping makes the curriculum more transparent to all the stakeholders (teachers, students, curriculum developers, managers, professionals and the public). It is a powerful tool for managing the curriculum[5] and is widely advocated in the generic skills literature.[6]

The use of the term 'mapping' reflects the process of connecting two or more data sets related to a curriculum, such as established content and the CanMEDS competencies.[7] Another vital function is that a map displays clear routes of learning that focus on work readiness. Mapping guides university teachers in integrating teaching content with occupational competence.[3] In addition, a curriculum map demonstrates the links between learning outcomes and learning opportunities and the links between the components of elements (e.g. between different learning outcomes).[3] Mapping can also be used as a method of operationalising outcome-based education and can play a role in determining whether the curriculum meets specific standards, i.e. whether the school's curriculum is congruent with the expected learning outcomes.[3]

Curriculum mapping can be used to identify gaps in a curriculum.[8] Web-based curriculum mapping is a feasible approach, as it enables alignment of complex, student-centred competencies with course-specific, well-defined behavioural objectives.[9] Although curriculum mapping has become a common activity, particularly at medical schools in the USA and Canada, there has been little standardisation or commonality of function and purposes for these maps. Implementation in the technology platforms used and the data sets drawn upon reflects local institutional needs and technological resources.[7] Various methods for curriculum mapping exist.[10] For example, in a generic skills mapping study, data were gathered using document analysis.[10] In another study, data for the curriculum maps were acquired through a review of course syllabi and interviews with course instructors.[8]

In a study by Willett,[11] medical schools in Canada and the UK were asked to indicate which outcome frameworks were included in their curriculum maps. As a consequence of this study, it seemed possible to consider the use of curriculum mapping in the current research. To date, no published literature exists regarding dental schools' in-practice implementation and translation of the AfriMEDS core competency framework within the SA context. This article aimed to describe curriculum mapping as a tool to demonstrate the alignment of an undergraduate dental curriculum with a competency framework, such as that of AfriMEDS, in preparation for accreditation and curriculum review.

Methods

A case study was used as the strategy of inquiry. This type of design enables researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of the situation and provides meaning for those involved.[12] According to Darke et al.,[13] single cases allow researchers to investigate phenomena in depth to provide rich description and understanding. Curriculum mapping was used in the current study to review the undergraduate dental curriculum. Although various electronic curriculum mapping systems are available, the researcher did not have access to them. Therefore, the curriculum mapping process was followed manually.

Veltri et al.[14] developed a conceptual framework for curriculum mapping that was based on a 'learning outcomes model'. This conceptual mapping framework was designed to include 5 different conceptions of the curriculum: intended, designed, communicated, enacted and assessed.[14] Definitions of the 5 conceptions are as follows:

• An intended curriculum comprises articulated statements of intended programme-level outcomes.

• A designed curriculum is reflected through degree plans and course sequences.

• A communicated curriculum consists of course-level outcomes and the specific teaching and learning activities listed in the course syllabi.

• An enacted curriculum refers to classroom pedagogies and the content, scope and depth of the material delivered by the instructor in the classroom.

• An assessed curriculum consists of the type and content of specific assessment tasks assigned to the students in a given course.[14]

For this study, the conceptual model of Veltri et al.[14] was modified to align with the needs of the UWC Dental School (Fig. 1):

• Step 1: AfriMEDS core competencies (intended programme outcomes)

• Step 2: designed curriculum (UWC dental curriculum; displayed as modules)

• Step 3: communicated curriculum (module learning outcomes).

The 2018 UWC dental calendar was used to evaluate the alignment of the undergraduate dental curriculum with the AfriMEDS core competency framework (intended programme outcomes). There are 59 modules (designed curriculum) from the first year of study to the final year (fifth year). All the module learning outcomes (communicated curriculum) in the module descriptors (n=59) were mapped against the AfriMEDS competency framework. In this research, the curriculum map was displayed in the form of tables, and competencies were colour-coded to ensure a simple and transparent result:

• Step 1 involved mapping the AfriMEDS core competencies: healthcare practitioner (HCP), communicator, collaborator, health advocate, leader and manager, scholar and professional (Tables 1 and 2).

• Step 2 involved mapping all the undergraduate dental modules (Tables 1 and 2).

• Step 3 involved locating the presence of the competencies relating to the AfriMEDS core competencies in the module-learning outcomes of each module. Related core competencies present within a module-learning outcome were quantified as numeric values (Tables 1 and 2).

These data provided an understanding of the curriculum context relative to the AfriMEDS competencies.

Peer debriefing as a validity strategy was used. A debriefing strategy involving an interpretation beyond the researcher and invested in another person adds validity to an account.[15] To ensure validity and reliability in the current study, the data were shared with a colleague who is a module co-ordinator at the dental school and a colleague from a different health science background. Comments from the colleague (peer) in the faculty were addressed and incorporated into the reported results. In addition to the insight and knowledge of this colleague regarding the content of the curriculum, this process facilitated reflection for the researcher. In deductive content analysis, the organisational phase involves categorisation matrix development, whereby all the data are reviewed for content and coded for correspondence with the identified categories.[16] The curriculum map processes that are described in steps 1 - 3 comprised the matrix development procedure. Trustworthiness and authenticity as criteria have been proposed for assessing qualitative studies.[17] Study respondent validation as a trustworthiness criterion is the process whereby the researcher provides the participants of the study with an account of the findings.[17] Findings of the generated curriculum map were shared with module co-ordinators during focus group interviews to ensure respondent validation. The use of quotations is necessary to indicate the trustworthiness of the results; quotations show connections between the data and the results and provide richness of data.[16] Quotes from the module outcomes extracted from the dental calendar, 2018, were included in the results of the current study.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Biomedical Research Committee, UWC (ref. no. BM19/1/27).

Results

The results are presented in three sections. Firstly, if present, the quantified competencies relating to the AfriMEDS roles in a module in the year of study are displayed in Table 1. The modules in each year of study (first column) and the presence of the roles (marked with 'X') are displayed in Table 2. Secondly, examples of the module outcomes (academic calendar, 2018) relating to the competencies and/or roles are described. Lastly, the results that describe the alignment of the AfriMEDS framework to the undergraduate dental curriculum of UWC are demonstrated.

Healthcare practitioner

Competencies relating to HCPs were present in the undergraduate dental curriculum in all 5 years:

• First year: 'Identify and describe the tissues of the periodontium, recognise and describe oral tissues in health and disease' - CLD100.

• Second year: 'Explain the physicochemical principles that underlie the properties of dental materials' - BDM.

• Third year: 'Describe the causative agent, reservoir, mode of transmission, signs and symptoms, pathogenesis, treatment and basic laboratory diagnosis of the major oral infections and infectious diseases of the body systems' - Medical Microbiology for Dentistry.

• Fourth year: 'Plan and manage extensive posterior restorations' - Conservative Dentistry 11.

• Fifth year: 'Integrate the principles of behaviour management and apply them to the comprehensive management of the child' -Paediatric Dentistry V.

Communicator

Competencies relating to communicator were present in all 5 years:

• First year: 'Explain the meaning of and generate academic text in oral health' -Academic Literacy.

• Second year: 'Discuss and apply various communication skills to effectively converse

with a patient' - CLD200.

• Third year: 'Explain to the patient the radiographic views to be done as well as the reason for taking them' - Radiographic Techniques.

• Fourth year: 'Communicate with the paediatric patient and the parent/caregiver as well as other health professionals' - Paediatric Dentistry Techniques.

• Fifth year: 'Communicate with the patient to elicit all pertinent information adhering to ethical code of practice at all times' - Oral Medicine and Periodontology III.

Collaborator

Competencies relating to collaborator were present in the first, third and fifth years:

• First year: 'Work productively in co-operative learning groups' - Chemistry.

• Third year: 'Work in a cross-disciplinary group using effective time management' -Measuring Health and Disease.

• Fifth year: 'Apply a multidisciplinary approach to patient management' - Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery.

Leader and manager

Competencies relating to leader and manager were present in the fifth year only:

• Fifth year: 'Apply the key principles of managing a successful dental practice' -Practice Management.

Scholar

Competencies relating to scholar were present in the first, third, fourth and fifth years:

• First year: 'Begin to develop life-long learning capabilities and to see chemistry as [a] discipline in a wider context' - Chemistry.

• Third year: 'Assess the quality and relevance of data used to describe community health and illness' - Measuring Health and Disease.

• Fourth year: 'Define a research problem, and describe the related aims and objectives' -Dental Research.

• Fifth year: 'Critically evaluate some aspect of health care delivery' - Health Systems.

Professional

Competencies relating to the role of a professional were present in the second and fifth years:

• Second year: 'Describe the role of the oral health team in South Africa' - CLD200.

• Fifth year: 'Describe key ethical, moral and social principles underlying the notion of human rights' - Ethics.

Health advocate

Competencies relating to the role of health advocate were present throughout the undergraduate dental curriculum:

• First year: 'Discuss the concepts of health, development and primary health care' - HDP.

• Second year: 'Explain the main approaches to health promotion' - HDP.

• Third year: 'Describe the community in relation to a variety of epidemiological indicators to measure the occurrence of health-related states in populations' - Measuring Health and Disease.

• Fourth year: 'Explain philosophical issues in prevention and health promotion' -Prevention.

• Fifth year: 'Recognise the main structural features of different health systems' - Health Systems.

Alignment of AfriMEDS to the undergraduate dental curriculum

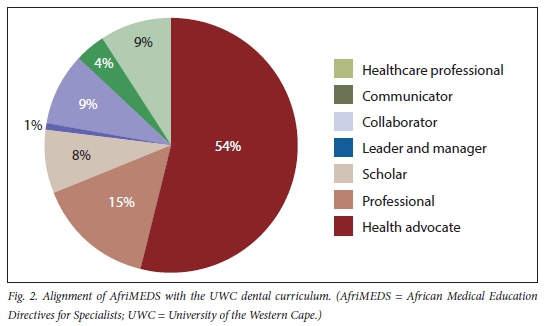

From the results of the curriculum mapping (Tables 1 and 2), the alignment of the UWC dental curriculum to AfriMEDS was demonstrated. It is clear that all the roles indicated by AfriMEDS were included in the curriculum (Fig. 2). This dental curriculum focused mostly on the healthcare professional (54% of curriculum), which is expected in a health professions training context. Inclusion of the other competencies was demonstrated to be much less. Communicator (15%) appeared to have an acceptable presence in the curriculum. However, collaborator, leader and manager, scholar, health advocate and professional roles were not very prominent, demonstrating a presence of <10% in the curriculum.

Discussion

This article describes how curriculum mapping could be used to demonstrate the alignment of an undergraduate dental curriculum with the AfriMEDS competency framework in preparation for accreditation and curriculum review. This research also developed a modified conceptual framework for curriculum mapping that may be relevant to other undergraduate dental programmes.

Studies have used the curriculum map to reveal curricular elements such as cultural competency that are difficult to recognise in a curriculum because the language of the learning objectives may not be sufficiently explicit even though the intended expectations of those objectives address the topic.[18] The AfriMEDS competencies were recognised in the UWC dental curriculum.

All the core competencies relating to the 7 roles, HCP, communication, collaborator, scholar, health advocate, professional, leader and manager, were present. In a study by Michael et al.,[19] the value of curriculum mapping as strategies for: (i) horizontal and vertical integration of geriatric-specific content in nurse practitioner curricula; and (ii) evaluation, improvement and curricula in health professional academic programmes, were described.

Competencies relating to HCPs were horizontally and vertically integrated within the UWC dental curriculum. It appears that the curriculum concentrates on the theory and clinical skills required to become a dental practitioner. This was more evident in the third, fourth and fifth years. Although communication was integrated vertically (within modules over the different years), the horizontal integration (within modules of the same year) is an area of development and should be considered during the curriculum review process. Similarly, scholar, health advocate and collaborator competencies (outcomes) were included vertically in all 5 years, but were not integrated horizontally.

Professional and leader and manager competencies were highlighted as roles that need to be developed both horizontally and vertically within the UWC curriculum. Professional competencies were only included in the second and final years. As suggested by Harden and Stamper,[20] a spiral curriculum implies the vertical and horizontal integration of themes/ competencies (as in this research) across and between disciplines and modules. If the example of communication competencies is used in this dental curriculum, it would suggest that these competencies should be taught from the first to the fifth year and within each year in different modules. Medical schools today are gradually departing from the traditional curricula to more integrated programmes,[18] and therefore the suggested integration of competencies into the UWC dental curriculum would ensure that this curriculum is relevant and current.

In addition to the research relating to the AfriMED competencies in the undergraduate dental curriculum, the use of a curriculum map to describe these competencies was implemented in this research. Furthermore, as there is no literature available that focuses on this subject, this research contributes to the current literature by describing the implementation and translation of the AfriMEDS core competency framework by the UWC Dental School. The study also illustrated the possibility of considering the use of a curriculum map as a tool for dental schools' accreditation purposes. For faculties involved in the preparation for accreditation, this tool would enable authentic visualisation of the entire curriculum. The presentation and simplification of the illustrated curriculum map could assist faculties in their preparations for accreditation in a non-threatening and structured manner. The unique modified conceptual model used in this research to outline the methods employed could be translated to similar settings. According to the literature, various methods for curriculum mapping exist,[10] depending on institutional or other needs. Although the intention of using a curriculum map was for accreditation purposes, the added benefit of identification of gaps or overlap in the undergraduate curriculum was highlighted.

Conclusion

Curriculum mapping is recommended as a valuable tool to navigate curriculum renewal or to be used as a starting point for curriculum development. The results of curriculum mapping in this study identified gaps or areas of development for the AfriMEDS competencies in the UWC dental curriculum. Alignment to curricula using other competency frameworks, such as the framework of CanMEDS, should be possible, as curriculum mapping is a reliable and valid tool. Moreover, the process of curriculum mapping identifies content overlapping and omissions.

Curriculum mapping is also recommended as a valuable tool to guide or to prepare for accreditation visits. It has the ability to display the 'big picture' or the authentic picture,[2] and the illustration of a curriculum map makes this possible. For faculties that are not comfortable with curriculum development, curriculum mapping allows for transparency of the curriculum.

Declaration. The research for this study was done in partial fulfilment of the requirements for RM's PhD degree at the University of the Western Cape.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. RM contributed 50%, RA 25% and JF 25% to the manuscript.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Medical and Dental Professions Board of the Health Professions Council of South Africa. Core Competencies for Undergraduate Students in Clinical Associate, Dentistry and Medical Teaching and Learning Programmes in South Africa. Pretoria: HPCSA, 2017:1-14. [ Links ]

2. Van Heerden B. Effectively addressing the health needs of South Africa's population: The role of health professions education in the 21st century. S Afr Med J 2013;103(1):21-22. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.6463 [ Links ]

3. Wang CL. Mapping or tracing? Rethinking curriculum mapping in higher education. Stud High Educ 2015;40(9):1550-1559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.899343 [ Links ]

4. Fritze O, Lammerding-Koeppel M, Boeker M, et al. Boosting competence-orientation in undergraduate medical education - a web-based tool linking curricular mapping and visual analytics. Med Teach 2019;41(4):422-432. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1487047 [ Links ]

5. Harden RM. AMEE Guide No. 21. Curriculum mapping: A tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Med Teach 200133(2):123-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590120036547 [ Links ]

6. Sumsion J, Goodfellow J. Identifying generic skills through curriculum mapping: A critical evaluation. High Educ Res Dev 2004;23(3):329-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000235436 [ Links ]

7. Ellaway RH, Albright S, Smothers V, Cameron T, Willett T. Curriculum inventory: Modeling, sharing and comparing medical education programs. Med Teach 2014;36(3):208-215. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.874552 [ Links ]

8. Rawle F, Bowen T, Murck B, Hong R. Curriculum mapping across the disciplines: Differences, approaches, and strategies. Collect Essays Learn Teach 2017;10:75-88. [ Links ]

9. Balzer F, Hautz WE, Spies C, et al. Development and alignment of undergraduate medical curricula in a web-based, dynamic Learning Opportunities, Objectives and Outcome Platform (LOOOP). Med Teach 2016;38(4):369377. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1035054 [ Links ]

10. Robley W, Whittle S, Murdoch-Eaton D. Mapping generic skills curricula: A recommended methodology. J Furth High Educ 2005;29(3):221-231. [ Links ]

11. Willett TG. Current status of curriculum mapping in Canada and the UK. Med Educ 2008;42(8):786-793. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03093.x [ Links ]

12. Merriam S. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and Expanded from 'Case Study Research in Education'. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998. [ Links ]

13. Darke P, Shanks G, Broadbent M. Successfully completing case study research: Combining rigour, relevance and pragmatism. Inform Syst J 1998;8(4):273-289. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2575.1998.00040.x [ Links ]

14. Veltri NF, Webb HW, Matveev AG, Zapatero EG. Curriculum mapping as a tool for continuous improvement of IS curriculum. J Inf Syst Educ 201132(1):31-42. [ Links ]

15. Creswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2009. [ Links ]

16. Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open 2014;4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633 [ Links ]

17. Bryman A. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012. [ Links ]

18. Al-Eyd G, Achike F, Agarwal M, et al. Curriculum mapping as a tool to facilitate curriculum development: A new school of medicine experience. BMC Med Educ 2018;18(1):185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1289-9 [ Links ]

19. Michael M, Wilson C, Jester DJ, et al. Application of curriculum mapping concepts to integrate multidisciplinary competencies in the care of older adults in graduate nurse practitioner curricula. J Prof Nurs 2019;35(3):228-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.01.007 [ Links ]

20. Harden RM, Stamper N. What is a spiral curriculum? Med Teach 1999;21(2):141-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599979752 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R Maart

rmaart@uwc.ac.za

Accepted 8 June 2020