Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 n.4 Pretoria Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2020.v12i4.1393

RESEARCH

Stakeholders' community-engaged teaching and learning experiences at three universities in South Africa

F MuzeyaI; H JulieII

IMPH, BSc Nursing; Department of Nursing, Faculty of Community Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

IIPhD, MPH, BCur Nursing; Department of Nursing, Faculty of Community Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Transformation forces in South African (SA) higher education and beyond have called for incorporation of community engagement into higher education. Specifically, the SA white paper 3 that informed the Higher Education Act No. 101 of 1997 mandated higher education institutions, including those involved in the training of nurses, to move towards community-engaged teaching and learning (CETL). An array of interventions has been implemented that aim at magnifying community-engaged pedagogical practices in SA universities, including nursing departments. However, this has not been without challenges.

OBJECTIVE. To describe stakeholders' CETL experiences at three SA universities.

METHODS. A phenomenological descriptive qualitative study using focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews was conducted with academics, students and community members at the health sciences departments of three universities that applied CETL approaches. Data were analysed through an inductive thematic approach and the outcomes are presented as themes.

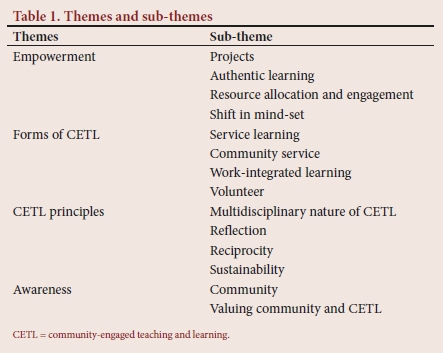

RESULTS. Four themes emerged from the data: empowerment; forms of CETL; principles of CETL; and awareness.

CONCLUSION. Stakeholders in CETL at the health sciences and nursing departments at three universities in SA indicated a rich array of experiences that can be used to leverage a transformative effect in nursing education. Appropriate integration of CETL into programme design and development of curricula, and use of explicit CETL methods with intentional outcomes for the students and communities, will go a long way toward achieving transformation in nursing education.

Community engagement (CE) in higher education is a contested field because of the diverse definitions linked to the concept, as argued in the literature.[1-3] The US Committee on Institutional Cooperation's Committee on Community Engagement defines it as 'the partnership of university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching, and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues, and contribute to the public good.['4] The purpose of CE is to magnify the impact that higher education has on students and the community.

In South Africa (SA), CE is integrated within higher education and forms part of institutional audit standards.[5] The Higher Education Act No. 101 of 1997 mandates for integrated higher education underpinned by research, teaching and CE.[6] An array of interventions aimed at magnifying community-engaged pedagogical practices at SA universities has been implemented. The Joint Education Trust launched the Community Higher Education Services Partnership that in 1999 brought in initiatives to improve CE at programme, institutional and national level and to conceptualise and implement CE as a core function of higher education in SA.[7] The SA Higher Education Community Engagement Forum (SAHECEF), formed in 2009, provides a national forum where 23 universities in SA are represented.

Higher education standards for nursing education implies approaches that will produce students who are able to impact health at community level. Nurses and other healthcare workers are crucial in helping to improve the health and wellbeing of populations, as well as in improving the social determinants of health (SDH) in communities. CE teaching and learning (CETL), including service learning, are approaches that increase students' competencies in SDH.[8] The State of the World's Nursing 2020 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that health science education, including nurse education, should prepare graduates who can improve the health and wellbeing of people by dealing with the SDH.[9] Indeed, Schroeder et al.[8] showed in their 2019 study that CETL in the form of service learning increased nursing students' knowledge and confidence in addressing SDH.

In addition, health sciences (including nursing curricula) are being redesigned so that they can answer to the new developments in higher education. These developments include the integration of nursing into higher education, the replacement of the traditional content-based curricula with outcomes-based curricula, and changes in relation to quality assurance standards, including the requirement that institutions and programmes fulfil CE obligations. A number of countries in Africa, and indeed worldwide, have engaged in nursing curricula redesign from traditional to outcomes-based curricula that emphasise performance of proficiency and community-based interventions.[10] The WHO recommended the transformation of health professions, including nursing education, so that it produces graduates who are responsive to the health needs of populations. The development of community-engaged curricula and social accountability in the education of healthcare professionals was one of the recommendations.[11]

CETL activities are aimed at improving the impact of health sciences education's preparation of graduates that will contribute to the overall wellbeing, including the health, of populations. Thus CE is a fundamental element for the solution of problems associated with SA higher education and society in general, otherwise inequalities and disparities among hosts of other problems will continue to persist.

There is a lack of structural and functional frameworks for the conceptualisation of CE in SA higher education institutions (HEIs).[2] Initiatives on CE by universities in SA have been ad hoc, disjointed and not related to the scholastic endeavour.[12] Currently there is no shared and cohesive definition for CE or CETL.[1,4,12] Although various SA institutions have attempted to develop contextual definitions, a coherent framework needs to be developed by South Africans for SA. This study was part of a larger study that aimed to develop a CETL typology for SA HEIs, rooted in the transformational agenda as expressed in the education white paper.[12] The review of curricula, including the incorporation of CE among other high-impact practices, is determined by the needs of various stakeholders in higher education, which includes students, educators and community members. Faculty, students and community are crucial stakeholders in CETL endeavours and indeed in curricular reforms.[9] The objective of this study was to explore the stakeholders' (academics/educators, students and community members) experiences of CETL at three SA universities.

Methods

Research design

A phenomenological descriptive qualitative approach was used to explore the stakeholders' experiences of CETL at three SA universities.[13-15] The study sought to explore how CETL is conceptualised, and to discern similarities among the stakeholders.

Population and sampling

Data were collected from three conveniently sampled universities that are members of the SAHECEF, with CE programmes as displayed on their websites. The sample for this study comprised academics (n=14), students (n=28), and community members (n=3) from the health sciences faculties of the included universities, who were identified though snowball sampling from recommendations by the board of directors of the SAHECEF. Semi-structured interview guides for individual interviews were used to collect data from the academics, students and community members, with 14 semi-structured interviews conducted with academics and community members across the three universities. Three focus group discussions (FGDs) (one per institution) with students were carried out, each of which included 8 - 10 participants.

Data collection

Ethical approval/clearance was obtained from the University of the Western Cape (ref. no. HS18/10/5), and institutional gatekeeper permission was obtained from the respective universities' research directorates. Access to collect data from each university department/faculty was obtained through the CE offices of two universities and the office of the Dean of Health Sciences for the other university. Data were collected through individual semi-structured interviews with academics and community members and FGDs with the students, observing ethical principles as guided by Burgess and Cilliers' framework.[16] The interview questions for both techniques were generated from the literature[17] and in consultation with an expert in CE in higher education (project supervisor/second author).

The first author piloted the data collection at one HEI in SA, and the necessary adjustments to interview questions were made. The focus of the interviews sought to explore the experiences of these stakeholders in CETL in their institutions. The interview questions were adjusted per population group. Individual appointments were made with each academic included in the study, at their convenience. The interviewed academic assisted the researchers in accessing students and community members within their institution who met the inclusion criteria.

All data were recorded, and field notes were taken during the data collection process. Data were collected between March and October 2019. The interviews and FGDs lasted between 29 and 76 minutes each, with a mean (standard deviation (SD)) of 46.8 (13.1) minutes, and were conducted by the first author.

Data analysis

The information from the interviews and FGDs was recorded by the first author and transcribed with the help of a transcriptionist (MA English student). Checking of the transcripts and coding was carried out by the first author, and ATLAS.ti 8 CAQDAS (ATLAS.ti, Germany) software was used to analyse the transcripts. An inductive approach was used for analysis, which created 41 codes. The transcripts were checked for quotations that implied experiences, and attribute, emotive, value and in vivo coding were used to generate codes.[181 The codes were then organised into 4 themes and 14 sub-themes. Assistance of a co-coder was sought, and agreement was reached between the first author and co-coder on the coding that was completed.

Results

Description of participants

Fourteen academics participated in this study, comprising 6 PhD holders and 8 Master's degree holders. These academics included nursing, radiography, dental therapy, somatology, biomedical technology and CE professionals. Twenty-eight students participated in three FGDs, made up of the following groupings: second-year BCur Nursing (n=10), second-year Diploma in Somatology (n=8), and fourth-year Bachelor's degree in radiography (n=10) students. The participants' ages ranged from 19 to 60 years, with a mean (SD) of 31 (13.5) years. Females made up the larger proportion of participants (82.2%, n=39) and males constituted 17.8% (n=8). The academic participants reported having between 2 and 5 years and an average of 3 years of CETL experience. Three community members participated in the study, representing community-based organisations that worked with primary and high school students, youth who were school-leavers and a university-based club.

Themes and sub-themes

Four themes emerged from the data, each with a number of sub-themes. The four main themes were as follows: empowerment; forms of CETL; CETL principles; and awareness. Table 1 lists the themes and sub-themes that emerged, and they are described in more detail in the sections that follow.

Theme 1: Empowerment

This theme had the following four sub-themes: projects, authentic learning, resource allocation and engagement, and a shift in mind-set.

Sub-theme 1.1: Projects. CETL projects that participants experienced and engaged in encompassed those related to health, education, and environment and community development aspects. In relation to health, interviews revealed that students engaged in experiential learning activities that entailed nutrition projects, as well as health education on oral hygiene, hand hygiene, safe sex, waste disposal, road safety and awareness about drug abuse. Projects on education included teaching science to primary school students and assisting high school students with homework and with applying for university admission and bursaries. Community development endeavours included income-generating projects. This sub-theme is illustrated by the following extract:

'We have wellness days where we host, like small that we do certain treatments [somatology treatments], maybe three. We host them at the libraries ... or at the sports centre. Even when it's career what what ... career expo, we also come to school as part of community service.' (02S (second institution student) FGD2 participant 7)

Sub-theme 1.2: Authentic learning. This study showed that CETL experiences were associated with different types of communities, including schools, informal settlements, townships, parents, teenagers, prisons, old people's homes, workplaces and the disabled. These included communities that were described as less privileged, rural or with fewer resources, diverse communities and those described in terms of being within a specified radius according to HEI policy. This is shown in the following extracts from participants:

'We go to our homes, schools, old age homes.' (O2FGD2 participant 6)

Currently, I would say a largest community that we target are young school children. Most of the communities we go and visit are schools, especially our less public schools, and we have targeted a crèche, although I haven't been, but we teach them how to wash hands and hygiene. So I think school is probably our largest target audience to do the education.' (O1E2 (educator 2))

Sub-theme 1.3: Resource allocation and engagement. Participants indicated how university resources were used to support CETL activities, including facilities for summits, acquisition of boreholes, mentors from the university and transport. Some universities have CE institutes and forums for students, academics and community members to share innovative ideas to support CETL. This is shown in the following extract:

Most of the things we do at the schools, but the university provides us with facilities for big events, like when we have summits. In summits, the learners engage with the professional, we give out the topic for the day and we have a debate. Usually the topic is something that is affecting all of us, like last year it was about free education, so that's what they were engaging about with the professionals. We had people from the [university name], even the chancellor was there as well. (O1C2 (community member2))

Sub-theme 1.4: Shift in mind-set. CE effecting change in frame of reference, transformative learning and attainment of graduate attributes emerged as major aspects that participants revealed in relation to students experiencing being empowered by the CETL activities. Participants' accounts showed that CETL activities affected the following on the part of the students: sense of responsibility; change from pessimism to valuing the experience; problem-solving abilities; and appreciation of the culture, norms and values of society, among other things. This is shown in the following excerpt:

'As future healthcare professionals, we are being trained to be citizens who care, those citizens who do something about the community, meaning that if like when we go to that community and experience things, we have to do something about it.' (03FGD3 participant 2)

Theme 2: Forms of CETL

This theme had four sub-themes, namely service learning, volunteerism, community service and work-integrated learning. These reflected a profile of CETL activities that participants, particularly students and academics, reported having experienced.

Sub-theme 2.1: Service learning. This sub-theme is illustrated by the following excerpt:

'Apart from the working, we also take part in service learning, which is more directly focused on the community and projects in the community.' (01E6)

Sub-theme 2.2: Community service. Another term that is used to describe a form of CETL experienced by the participants is community service:

' We do community service, it's part of the curriculum . I think . academic curriculum. We go to homes, schools, old age homes and we do treatments that we usually do here at school and in return we get hours.' (O2SFGD2 Part. 6)

Sub-theme 2.3: Work-integrated learning. This sub-theme is illustrated by the following excerpt:

Also, we have a take-a-learner-to-work day where people who are working from the organisation do take a few learners with them to work on that take-a-person-to-work day' (O1C2)

Sub-theme 2.4: Volunteer activities. One other form of CETL reflected by the interviews with stakeholders included volunteer activity. This is shown in the following extract:

'We usually encourage the students to come and volunteer with us here' (O1C3)

Theme 3: Principles of CETL

This theme had four sub-themes, namely the multidisciplinary nature of CETL, reflection, reciprocity and sustainability. Another feature was that a profile of frameworks was used to undergird pedagogical practices, including constructivist, problem-based approaches, using Sustainable Development Goals and the National Development Plan to guide the CETL activities. This is shown in the excerpts below:

' They must teach the community something and at the same time they must also learn something from the community.' (01E3)

' The students learn how to handle these situations as professionals and then how to work with multidisciplinary teams; if we find out that this is social problem ... how to refer to the relevant stakeholders.' (03E4)

Theme 4: Awareness

This theme related to awareness and had two sub-themes, namely awareness of the community, and valuing the community and CETL.

Sub-theme 4.1: Awareness of the community. Participants' interviews identified experiences of an improved awareness of the community in various cultural, political or social aspects. Stakeholders had a consciousness of community challenges, appreciation of other cultures, and gained professional socialisation through engagement in CETL activities. This is illustrated in the following excerpt:

'Behaviour-wise I think they now know more about what's going on out there in the world, not just being confined to the [university] environment. So in terms of behaviour, they've become more open-minded, I would think.' (02E2)

Sub-theme 4.2: Valuing the community and CETL. CETL activities taught stakeholders to value the community and to value CETL approaches, as shown in the following quote:

' From my viewpoint, yes indeed community engagement is important for students, and the community, more especially with the nursing students because in nursing, a nurse is always a nurse anywhere. Like in the community, hence it is important to involve the community in the students' learning, so that they can be able to form the relationship with the community that they serve.' (03E3)

Discussion

A phenomenological descriptive approach was used to describe similarities of experiences with regard to CETL among stakeholders (students, academics and community members) at the nursing and health science departments of three universities. This exploration yielded themes relating to participants' experiences of empowerment, forms of CETL, principles of CETL and awareness.

The experience of CETL is shown as empowering by the stakeholder accounts in this study. CETL creates authentic learning experiences for students, which enhances their ability to achieve their competencies by the time of graduation. Additionally, effects on academics and community participants in CETL encounters are also recorded, and this corroborates the findings of previous studies.[19,20] However, Boyle-Baise et al.[21]argue that CETL in its ideal form should 'destabilise inequitable distribution of power, privilege and knowledge. Furthermore, these authors elaborate that service for social justice examines injustice, deepening students' grasp of equity, and fostering activism. This is not evident from the students' experiences in this study.

The study findings illustrated that CETL activities can be implemented and integrated into curricula in various ways. This is corroborated by the literature, which describes various forms of CE teaching. This includes service learning, which is distinct from community service or volunteerism in that it focuses on the learner in addition to the communities served.[22] A differentiation between service learning and volunteerism is also made by identifying that the former 'integrates service in the community with intentional learning activities', while the latter 'involves all kinds of learning, but most of the learning in volunteerism is not implicit or unintentional'.[22] Work-integrated learning is described as an approach to teaching and learning that integrates what students have learned at the HEI through workplace experience. The literature shows utilisation of CETL in nursing and health sciences education.[19,20]

In relation to principles of CETL, the study indicates the involvement of various stakeholders in CETL activities, which is a requirement if such a pedagogical approach is to be effective. The role of CETL in magnifying student transformation in higher education is shown in this study. This is corroborated by Boyle-Baise et al.,[21]who argue that deliberately exposing students to CETL activities helped to develop civic commitment, including a sense of social responsibility.

Participants' experiences in this study furthermore revealed an improved awareness of the community. Indeed, Olson and Brennan[23] argue that CETL activities lead to what they call development of community and development in community. They describe development of community as a process-motivated emergence of community that represents the 'coming together of people to discuss and act upon issues '.1 of greater value than outcome or outcomes'.[23] Development of community is biased towards outcomes such as improvement in built and natural environment of an area.[23] These study findings reveal the potential that CETL has in prompting development of community as stakeholders develop awareness in the process of engaging in CETL activities.

The optimal realisation of CETL principles is important for the context of SA, if nursing and health sciences education are to realise the transformative agenda as outlined by the White Paper on Higher Education of 1997.[24]

Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal the opportunities that abound for health sciences education and indeed nursing education through utilisation of high-impact approaches such as CETL. The study showed a rich array of strategies that can be used to leverage the transformative effect of teaching and learning in nursing education. Appropriate integration of CETL into programme design and development of curricula, and use of explicit CETL methods with intentional outcomes for students and communities, will go a long way to achieving transformation in nursing education.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to acknowledge the students, academics and community members from the three universities who participated in this study. Furthermore, the authors would like to acknowledge Dr C Nyoni (School of Nursing, University of the Free State) for a critique of the manuscript.

Author contributions. FM (University of the Western Cape (UWC)) is the doctoral candidate who researched and wrote the article. HJ (UWC) is the doctoral supervisor, who provided support especially during the conceptualisation phase, review and write-up of this article.

Funding. National Research Foundation.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Driscoll A, Sandmann LR. From maverick to mainstream: The scholarship of engagement. J High Educ Outreach Engagem 2016;20(1):83-94. [ Links ]

2. Kasworm CE, Abdrahim NAB. Scholarship of engagement and engaged scholars: Through the eyes of exemplars. J High Educ Outreach Engagem 2014;18(2):121-148. [ Links ]

3. Rawlings-Sanaei F, Sachs J. Transformational learning and community development: Early reflections on professional and community engagement at Macquarie University. J High Educ Outreach Engagem 2014;18(2):235-260. [ Links ]

4. Fitzgerald HE, Bruns K, Sonka ST, Furco A, Swanson L. The centrality of engagement in higher education. J High Educ Outreach Engagem 2016;20(1):223-244. [ Links ]

5. Council on Higher Education. Criteria for Programme Accreditation. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education, September 2004, revised June 2012. [ Links ]

6. Council on Higher Education. Community Engagement in South African Higher Education, Kagisano No. 6. Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2010. [ Links ]

7. Lazarus J, Erasmus M, Hendricks D, Nduna J, Slamat J. Embedding community engagement in South African higher education. Educ Citizenship Soc Justice 2008;3(1):57-83. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1746197907086719 [ Links ]

8. Schroeder K, Garcia B, Phillips RS, Lipman TH. Addressing social determinants of health through community engagement: An undergraduate nursing course. J Nurs Educ 2019;58(7):423-426. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20190614-07 [ Links ]

9. World Health Organization. State of the worlds nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. Geneva: WHO, 2020. [ Links ]

10. Nyoni CN, Botma Y. Integrative review on sustaining curriculum change in higher education: Implications for nursing education in Africa. Int J Afr Nurs Sci 2020;12:1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100208 [ Links ]

11. World Health Organization. Transforming and scaling up health professionals' education and training: World Health Organization guidelines 2013. Geneva: WHO, 2013. [ Links ]

12. Hester J, Adejumo OA, Frantz JM. Cracking the nut of service-learning in nursing at a higher educational institution. Curationis 2015;38(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102%2Fcurationis.v38i1.117 [ Links ]

13. Reiners MG. Understanding the differences between Husserl's (descriptive) and Heidegger's (interpretive) phenomenological research. J Nurs Care 2012;01:5. https://www.omicsgroup.org/journals/understanding-the-differences-husserls-descriptive-and-heideggers-interpretive-phenomenological-research-2167-1168.1000119.php?aid=8614 (accessed 25 July 2020). [ Links ]

14. Lopez KA, Willis DG. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual Health Res 2004;14(5):726-735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304263638 [ Links ]

15. Starks H, Brown Trinidad S. Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res 2007;17(10):1372-1380. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732307307031 [ Links ]

16. Burgess T, Cilliers F. A framework for ethical educational research: Principles and application. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Educational Development Unit, 2016. www.healthedu.uct.ac.za/framework-ethical-educational-research-principles-and-application (accessed 5 August 2018). [ Links ]

17. Stellenbosch University. Social impact strategic plan. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, 2016. [ Links ]

18. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage Publications, 2009. [ Links ]

19. Tyndall DE, Kosko DA, Forbis KM, Sullivan WB. Mutual benefits of a service-learning community-academic partnership. J Nurs Educ 2020;59(2):93-96. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20200122-07 [ Links ]

20. Sandberg MT. Nursing faculty perceptions of service learning: An integrative review. J Nurs Educ 2018;57(10):584-589. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20180921-03 [ Links ]

21. Boyle-Baise L, Brown R, Hsut M-C, et al. Learning service or service learning: Enabling the civic. Int J Teach Learn High Educ 2006;18(1):17-26. [ Links ]

22. Van Styvendale N, McDonald J, Buhler, S. Community service-learning in Canada: Emerging conversations. Engaged Sch J Community-Engaged Res Teach Learn 2018;4(1):i-xiii. [ Links ]

23. Olson B, Brennan M. From community engagement to community emergence: The holistic program design approach. Int J Res Serv-Learn Community Engagem 2017;5(1). [ Links ]

24. Department of Higher Education and Training, South Africa. Education White Paper 3. A Programme for Higher Education Transformation. Pretoria: DoHET, 1997. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

F Muzeya

3718239@myuwc.ac.za

Accepted 24 August 2020