Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 no.4 Pretoria nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2020.v12i4.1431

SHORT RESEARCH REPORT

Supportive framework for teaching practice of student nurse educators: An open distance electronic learning (ODEL) context

T E Masango

PhD (Nursing Education) Department of Health Studies,University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Teaching practice is an integral part of the preparation of student nurse educators. It provides students with an opportunity to translate theory into practice and to gain knowledge and skills to become effective and competent nurse educators.

OBJECTIVES. The study sought to explore experiences of student nurse educators who attended a teaching practice workshop (students attend one session for 5 days at the third-year level of training) and to develop a supportive framework to enhance the acquisition of pedagogical skills.

METHODS. A qualitative, phenomenological research design was used. Out of 35 participants who attended the workshop, 20 consented to participate in the study. Data were collected through written narratives and analysed using thematic content analysis. A purposive sampling technique was followed.

RESULTS. Most participants reported a number of challenges experienced during teaching practice, which were grouped into six themes, namely: poor orientation, lack of adequate support by supervisors, teaching strategies not aligned with open distance electronic learning, expectation of doing a PowerPoint presentation without prior knowledge, use of an outdated study guide, and limited time for teaching practice.

CONCLUSION. Orientation of students for teaching practice needs to be detailed, accessible online after sessions, and conducted via video classes, podcast, smartboards, etc. before a workshop. Support and guidance should be provided through prompt feedback on lesson planning and online classes to teach principles and procedures of lesson presentation. Promotion of computer skills and allocation of more time for teaching practice are necessities.

Nurse educators are not born to be teachers, but becoming effective at teaching requires special knowledge and skills.[1] This competency is achieved by student nurse educators (SNEs) undergoing teaching practice (TP) sessions to acquire pedagogical skills and learn how to teach. In South Africa (SA), preparation of nurse educators is done at universities by departments of nursing science. At the institution concerned in the present study, TP is a component of a bachelor's degree programme leading to registration as a nurse educator. The degree is offered online, as the university is an open distance electronic learning institution (ODEL). It is undertaken by students who are at their third-year level of training in a simulated environment for a period of 1 week.

Simulation workshops are a common feature of student teacher preparation and are done in other countries to teach SNEs how to teach. In India and Iraq, TP is termed a simulation workshop and forms part of SNE preparation as an educator.[2]

The link between theory and practice is often skewed in favour of theory. The one-week exposure of SNEs currently practiced at the institution under study is short, to enable them to rapidly acquire the requisite pedagogical skills.

Objectives

The aims of the study were to:

• explore the experiences of SNEs who attend the TP workshop

• gather suggestions from participants on improving TP

• develop a supportive framework to guide and enhance TP.

Methods

A qualitative, phenomenological research design to gain insight into the depth, richness and complexities inherent in the lived experiences of SNEs

who attend TP workshops was adopted. TP workshops at the institution under study are spread over a period of 3 months, from June to September of each year. Data were obtained from two groups: the first group (9 students) attended between 14 and 18 July 2018 and the second group (11 students) between 14 and 18 August 2018.

Using non-probability purposive sampling, a total of 20 (out of 35) SNEs participated in the study after signing consent forms. Data were obtained from SNEs using written narratives as proposed by Hopwood and Paulson.[3]Participants were requested to reflect on their experiences and to write them down on the narrative guide that was given to each participant. The guide included two questions:

• Share your experiences on TP workshops you have attended.

• How can the quality of TP workshops be enhanced for maximum acquisition of pedagogical skills? Give suggestions.

Data were analysed using Tesch's (1990) eight steps of the coding process. The researcher read and re-read written narratives, identifying similar ideas and patterns which were coded and grouped together into themes.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Health Studies Research and Ethics Committee (HSREC) of the Department of Health Studies, University of SA, and the College Ethics Committee (ref. no. HSDC/821/2017).

Results and discussion

Participants were requested to indicate their experiences during TP workshops and to suggest solutions for improvements. A mixed bag of responses were given, of which the negatives outweighed the positives. Themes that emerged were: poor orientation, lack of support, use of teaching strategies not aligned with ODEL, use of technology without preparation, outdated study guide, and a short period of time for TP, leading to poor mastering of teaching skills.

For each negative experience, participants were requested to suggest solutions to alleviate the challenges experienced during TP. Suggestions included:

1. Improved orientation practices

Findings revealed that orientation was poorly done, making students frustrated, anxious and without any clarity regarding how to prepare for TP and what to expect. Participants suggested extending the orientation period to 2 weeks:

There should be more orientation before the workshops to prepare more effectively and efficiently. Unsure of certain things like case study - should be clearer - and state it is "problem solving" was misinterpreted.' (P3)

'... I was not happy with the online orientation because I was unable to watch it later that day. As an open distance learning, I feel the online presentations should be available anytime for those who were busy during the presentation time to watch it later.' (P5)

Poor orientation of SNEs was also mentioned in a study conducted by Summers,'41 where SNEs reported inadequate preparation and support; this was contrary to the view that good orientation with formal mentor support and clear direction about role expectation are essential in nurse educator preparation.

2. Use of transformative teaching strategies

Participants' views were divided among those who had resources such as computers and internet access v. those without technological resources. Participants suggested teaching strategies that are in line with ODEL such as video classes, podcast and smartboards; others preferred conventional teaching methods:

'. As student nurse educators, we must be taught teaching strategies in line with ODEL, such as podcast, interactive chart forums etc' (P15)

'. Teaching methods for rural areas and colleges must also be accommodated. Not every student has access to computer or internet access.' (P20)

3. Effective and adequate support

Poor student support during preparation for the workshop emerged as yet another issue:

'... Little/no guidance with preparation of the lesson plans.' (P4)

A mock demonstration was suggested before the

start of the teaching session:

'...Demonstration before practicals to be given to get a chance to learn as we are here to learn' (P8)

The same findings were reported by Musin-gafi et at.,[5]where student teachers reported inadequate academic support by facilitators.

4. Inclusion of technology lessons in the TP programme

Some participants indicated they had never used acomputer before and need to be taught basic computer skills including PowerPoint:

'...To have a teaching session on basic computer skill and PowerPoint presentation.' (P17)

Inclusion of technology in the nursing curriculum is supported by Gonen et al.[6]who propound that informatics and technology need to be accommodated within the nursing curriculum, including different types of electronic health record.

5. Updating of study guides and extension of workshop period

The workshop period was too short to ensure adequate learning; 2 weeks were recommended and that the study guide must be updated:

'... Teaching practice has a lot of work and one week is not enough.' (P2)

The study guide must match what is expected on the actual practical session. UNISA used outdated study guide.' (P6)

Most participants indicated that the TP workshop period should be extended to give them enough time to learn teaching skills.The same sentiments were shared by Mukumbang and Alindekane,'71 who stated that there was an unequal link between theory and practice in the preparation of nurse educators. They viewed this as one of the basic problems in SNE preparation.

Some participants indicated that the mentoring and coaching received was beneficial in their preparation as educators, but the majority felt unsupported by the facilitators.

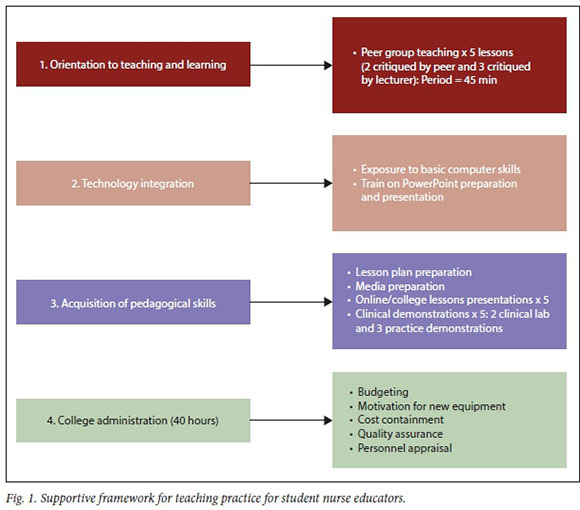

The findings from this study prompted the researcher to develop a teaching practice supportive framework (Fig. 1) with the purpose of enhancing TP and improving the acquisition of teaching skills by students. The practice- oriented theory by Dickoff as cited by Justus and Nangombe[8] was used to guide the development of the framework, and prescripts of the South African Nursing Council regulations (R118) were incorporated.

Conclusion

Findings from the present study concluded that orientation of students for TP workshops should be detailed; conducted via online platforms such as video classes and podcasts, etc.; and accessible online after sessions for referral purposes during preparation. Student support should be strengthened to promote learning of teaching skills, study guides be regularly updated, lessons on computer skills be provided, and duration of the workshop be extended. Well-planned and well-executed TP sessions are critical in the preparation of nurse educators. There is a need to develop a supportive framework to improve TP.

Declaration. The article is based on a study conducted by the researcher during research and development leave.

Acknowledgements. The researcher thanks students who participated in this study.

Author contributions. Study conduction, and drafting and critical revision of the article, were done by the researcher.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Lateef AM, Mhlongo EM. Factors influencing nursing education and teaching methods in nursing institutions: A case study ofSouth West Nigeria. Glob J Health Sci 2019;11(13):13-24. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v11n13p13 [ Links ]

2. Garner SL, Killingsworth E, Bradshaw M, et al. The impact of simulation education on self-efficacy towards teaching for nurse education. Int Nurse Rev 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12455 [ Links ]

3. Hopwood N, Paulson J. Bodies in narratives of doctoral students' learning and experience. Stud High Educ 2012;37(7):667-681. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.537320 [ Links ]

4. Summers JA. Developing competenciesin the novice nurse educator: An integrative review. Teach Learn Nurs 2017;12(4):263-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2017.05.001 [ Links ]

5. Musingafi MC, Mapuranga B, Chiwanza K, Zebron S. Challenges for open and distance learning (ODL) students: Experiences from students of the Zimbabwe Open University. J Educ Pract 2015;6(18):59-66. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-3-10A-3 [ Links ]

6. Gogen A, Sharon D, Levi-Ari L. Intergrating information technology's competencies into academic nursing education. An academic study. Congent Educ 2016;4(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1193109 [ Links ]

7. Mukumbang FC, Alindekane LM. Student nurse educators' construction of teacher identity from a self-evaluation perspective: A quantitative case study. Nurse Open 2017;4:108-115. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.75 [ Links ]

8. Justus AH, Nangombe JP. Paradigmatic perspective for a quality improvement training programme for health professionals in the ministry of health and social services in Namibia. Int J Health 2016;4(2):89-95. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijh.v4i2.6164 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

T E Masango

masante@unisa.ac.za

Accepted 5 October 2020