Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 no.3 Pretoria oct. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2020.v12i3.1363

RESEARCH

Liberalisation of education in Cameroon: The liberating-paralysing impact on nursing education

M N Maboh

PhD; Department of Nursing, School of Health Sciences, Biaka University Institute of Buea, Cameroon; and Centre for Innovation, Education & Research Development, Health Research Foundation, Buea, Cameroon

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Developing nursing's capacity to influence relevant government policies is a goal of organised nursing. This is challenging for countries such as Cameroon with centralised systems of government, where organised nursing has few to no structures to influence relevant policies, including nursing education policies. However, government may at certain moments pursue policies that have unintended effects on nursing. The Cameroon government's liberalisation of education was one such policy that, though not specifically targeted at nursing, continues to affect nursing education in Cameroon.

OBJECTIVES. This study sought to explore the nature and effect of the liberalisation policy on nurse education in Cameroon.

METHOD. The study design was based in constructivist grounded theory, a contemporary interpretation of grounded theory. Audio-recorded interviews were conducted with a sample of 10 nurses, purposively drawn from nurse education leadership. Government policy texts on nurse education from independence to present, and interview transcripts, were imported into NVivo 10 software for analysis.

RESULTS. Results showed that liberalisation was based on a 2001 law that officially approved private higher institutes of learning. This led to the start of nursing programmes in these institutes and in universities, leading to the awarding of degrees hitherto unavailable in the country. Some nurses quickly embraced these changes, while others actively resisted them. Analysis of these interacting forces revealed a state of liberalising paralysis that fails to adequately advance nursing education.

CONCLUSION. A strong nursing body with long-term strategic goals is needed to maximise opportunities where government policy such as liberalisation inadvertently favours professional growth and advancement.

Contemporary nursing has significantly progressed since the Nightingale era. Entry to practice in many countries is now set at the Bachelor's level. The scope of practice is widening: nurses now have prescribing rights; lead in chronic disease management; and provide increasing access to quality care, at relatively affordable costs.[1] Nurses even run primary care services employing general practitioners.[2] They play leading roles in developing care models that deliver better patient outcomes.[3] Their role in healthcare policy development is also increasing. Hall-Long[4] has argued that their proactive involvement in health policy development drives excellence in nursing practice, scholarship and education.

Despite the progress made, some nurses in clinical settings avoid becoming involved in policy debates.[5] In some cases, nurses' role in health policy development remains unclear.[6] Ellenbecker et al.[7] propose educating nurses in health policy to solve this problem. However, education alone will not solve the problem. Rafferty[2] has observed that nurses' voice in policy development has always been weak. Their presence and status in policy decision-making is minor,[8] and even in cases where they have the competence, their voices are not heard. [9]

Health policies, like other national policies, are usually determined by governments. If nurses want national policies to reflect nursing values, they will have to influence those policies.[10] This means that they need to skillfully align their goals with government interests. Three conditions are necessary for this to happen: first, the context has to be ready for change; second, the interests of the profession and the government need to align; and third, some contingency or factor is needed to create an intervention urgency.[11]

Cameroon is a central African country with a centralised system of government. Nursing education until the late 1990s and early 2000s was controlled by the Ministry of Health (MOH), and was diploma-based.[12] The Ministry of Higher Education (MHE) and the Ministry of Employment and Vocational Training (MEVT) began running nursing programmes at the time of the liberalisation laws of the early 2000s. While all three ministries ran diploma programmes, only the MHE could run degree programmes. Considering organised nursing's relative lack of influence over government policy structures, nursing has struggled to respond to these changes. The present study, conducted as part of an investigation of nursing education in Cameroon, analyses the effect of the liberalisation of higher education (HE) on nursing education.

Methodology

Design

The study design followed Charmaz's[13] contemporary interpretation of grounded theory as described by Glaser and Strauss.[14] She proposed an early sorting and synthesis of data through qualitative coding and building levels of abstraction from the studied data.

Participants and data collection

Study participants were (i) nurses in leadership roles in nursing education and administration in Cameroon; and (ii) government policy texts on nursing education from the 1960s to 2016. Nurses were selected using purposive sampling, and invited to take part in semi-structured interviews.

Theoretical sampling - 'the process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes and analyses data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them, in order to develop the theory as it emerges'[14] - guided follow-up interviews and further data searches. A sample size of 10 nurses was set at the beginning of the study. Documents were collected from the MHE, MEVT and MOH.

Analysis

Document analysis began once the documents were collected. Applying Charmaz's framework,[13] meanings, beneficiaries, context and patterns within the documents were isolated. Document analysis enables exploration of historical foundations of contemporary ideas, practices and identities that subtly affect the present. [15] Texts were examined for context, target, and direct and implied meanings, as Charmaz[13] recommends. This analysis also generated new questions that were pursued in the interviews.

Interviews lasted between 40 and 60 minutes, and were audio-recorded and guided by an interview schedule. The research questions constituted the primary questions, while responses and emerging data generated follow-up questions. Analysis from the 10 interviews generated new issues that required 3 secondary interviews, including 1 new participant who met the study criteria. This participant had mastery of the new issues. Actions such as this were previewed in the ethical clearance. Interview transcripts and scanned copies of documents were then imported into NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Australia) for qualitative analysis. Data were coded beginning with line-by-line coding. Focused codes were then created by merging codes capturing similar data. Constant comparison of data, codes and focused codes led to the identification of subcategories illustrating the links between focused codes. With the growing complexity of emerging data, explanatory links between subcategories were identified, leading to categories. Memos were also written to question and expand on emerging data.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Essex, UK, and the University of Buea, Cameroon (ref. no. 2015/346/UB/FHS/IRB), where the study was carried out. Participants gave written consent, and interviews were conducted at their convenience and with their rights respected.

Results

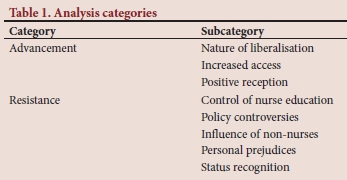

There were two categories constructed, 'advancement' and 'resistance' (Table 1). Advancement captured three subcategories that showed liberalisation positively affecting nursing education, as perceived by study participants. Resistance captured the complex links between five subcategories showing resistance to liberalisation-associated changes.

Advancement

This category describes the nature and positive effects of liberalisation, and is composed of three subcategories.

Nature of liberalisation

The passage of law No. 005 of 2001 liberalised HE in Cameroon by approving private higher education institutions (PHEI):

'HE is made up of all programmes and post-secondary education provided by public HE institutions and private higher institutions authorised as higher institutions by the state.' (Law No. 005, 2001)

Liberalisation changed perceptions about education among participants:

'As scientific profession is coming on ... as different fields of specialties are coming up for the wellbeing of the patient, people should be given the opportunity to excel in whatever domain they want and not to have limiting factors.' (interview 12: quote2)

Contemporary educational systems should thus be responsive to individual needs and scientific progress, and give professionals the opportunity to excel.

The policy also increased educational opportunities: 'Formerly the nurse could not go beyond the so called CESSI 'Centre for Higher Nursing Studies1 advanced nursing diploma . when things were liberalised, it seemed as if many people understood that no profession should be held ransom.' (Int12:1)

Education opportunities beyond the diploma felt like professional liberation to some nurses.

Increased access to education

Liberalisation introduced nurse education to the university. Nurses with MOH diplomas with 5 years' practice experience were also admitted to study for the 4-year Bachelor's degree:

'When they announced the entry into the BSc section for UB 'University of Buea] in 1997, they considered the new entry and the old or experienced nurses . professionals who were ready and had more than 5 years' experience were opportuned to get in . I got in and so succeeded to do my BSc nursing.' (Int10:1)

More universities now offer the 4-year Bachelor's degree programme:

'There are other universities that have also come up both public and private that are also training at the Bachelor's level. We can take the Christian university ... the Catholic University in Yaoundé ... the University of Bamenda.just to name a few . that are actually delivering a Bachelor of Science programme in nursing. Straight 4-year programmes.' (Int7:1)

The MHE, in addition to degree programmes, also launched the higher national diploma (HND) programme:

'So around 2003 or so . launched its HND programme to train nurses again at the diploma level, but this time using an HE model not a hospital-based type of model . giving those nurses the opportunity to advance in the HE system becoming Bachelor of nursing, masters ... etc.' (Int7:2)

The HND model was not hospital-based, but designed to allow advancement to undergraduate and postgraduate degree studies.

The expansion brought about increased recognition of the Bachelor's degree within the MOH:

'I think things have ameliorated themselves, once you want to go to school now, you ask for authorisation, you are given the authorisation. When you come back and give your report and hand in your papers you will be placed' (Int10:2)

After initial resistance to nursing degrees, the MOH created a process to recognise nurses' HE qualifications.

Expansion equally created a wide variety of nursing programmes:

' There is a lot of multiplicity in our nursing as we move to HE, which is a good thing anyways - the nurse was not meant to stagnate.' (Int3:3)

Some participants saw the multiplicity of nursing programmes as a growth opportunity. Some nurses wanted the MOH to stop running nursing programmes. These programmes are still diploma-based, while MHE programmes are degree-based:

'MOH who is the employer feels that they should follow its ideology; unfortunately, times have changed. We cannot be following your ideology when you are ending at the diploma level and some of us are ending at the Bachelor's level.' (Int7:3)

Only the MHE can issue degrees. Since MOH programmes lack a clear diploma-Bachelor bridging pathway, some nurses perceived them as outdated.

Positive reception

Constant comparison revealed data showing that the expansion of nursing education was welcomed. There was the perception of rediscovery:

'We now realise there was something we were missing. Now they are going for it, to expand the scope of these disciplines.' (Int1:1)

Nurses saw an opportunity to grow their capacity and expand their scope of practice. This was facilitated by PHEIs providing diploma-Bachelor bridging courses:

'Without any written policy some private schools now, I must say PHEIs, are giving those nurses ... the opportunity to convert their SRN diplomas to a degree.' (Int7:1b)

The bridging courses were designed only for HND holders, but PHEIs innovatively designed special diploma-Bachelor bridging courses for MOH diploma holders. Though both are 3-year diplomas, these bridging courses take 1 and 2 years, respectively.

Some nurses took credit for the ongoing expansion:

' We fought for this, fought for it seriously . so we are very happy with what is happening today.' (Int6:1)

Though the ongoing changes resulted from a general government policy, some nurses believe their lobbying played a role.

Resistance

This category revealed five subcategories showing resistance to liberalisation-associated change.

Control of nurse education

Some nurses think that only the MOH should control nursing education:

' These are health personnel, in some settings there can be no health personnel who will not train within the . MOH context . but now they just diffuse the whole thing ... What type of certificates does ministry of professional training give them?' (Int13:1)

The training programmes under other ministries were looked on with suspicion. This suspicion was strengthened by the perception that the other ministries had weaker accreditation procedures, and so non-health personnel went there for accreditation:

'When we were in the MOH, there were many applications from people who wanted to open schools, economic operators, but . they were not qualified so they now went them into vocational education ... and opened schools, got their authorisation from there.' (Int1:1)

For other nurses, this argument was more about control than quality:

'There is no rationale, there is no rationale! Again, it has to do with what we call protecting your turf.' (Int7:1)

Policy controversies

The ministries operated parallel education models:

'MOH continues with its trajectory of training nurses in its hospitals-based ... curriculum while the MHE is using the LMD or the Bachelors-Masters-PHD model to train nurses along the university curriculum. So the problem is: what will be the fate of the nurses who are continuing to be trained by MOH?' (Int7:3)

The two parallel models, the MOH hospital-based, and the HE Bachelors-Masters-PhD model (allowing a smooth transition from Bachelor through doctoral studies) were mutually exclusive. So, while MHE diploma holders could easily progress to postgraduate studies, the MOH diploma holders could not.

The diploma-Bachelor bridging pathway remained a complex system within HE:

'Candidates with the HND . after 1-year conversion . get their bachelor's degree. But . the state universities are not doing it . One would think that it would have been automatic now for HND students to just enroll in the university system . but the university is not doing it.' (Int7:4)

PHEIs offer a 1-year HND-to-Bachelor bridging course, through their affiliation with state universities. However, these courses are not directly obtainable from the universities. Another controversy was the curricular diversity:

'There is no control; everybody has his own independent training programme curriculum ... meanwhile, everybody should be on the same footing.' (Int8:2)

The perceived curricular diversity among PHEIs in contrast to the MOH's national curriculum was interpreted as evidence of disorganisation.

Influence of non-nurses

The data revealed the strong influence of physicians and non-nurses on nurse education. Non-nurses were perceived to be actively involved in shaping education policy:

'The training of nurses in this country is in the hands of people who are not nurses, and they don't understand how nurse training should be like. ' (Int9:1)

Many proprietors of PHEIs were non-nurses, and this gave them influence over nursing programmes within their institutions. These proprietors, some of whom were physicians, were seen to prioritise profits over professional standards:

"It's the quest for economic power by the doctor. They know that to get rich quick, open a nursing school of course ... therefore the financial aspect of it ... overrides nursing care practice.' (Int3:3)

Personal prejudices

Educational expansion created job insecurities and encouraged resistance. Some nurses were afraid of losing their positions to more qualified graduates:

'They somehow feel threatened that if they allow training to move into the universities . young people will come out with higher qualification and that may jeopardise their jobs and their position.' (Int9:1)

Data also showed professional subjectivity:

'I think that people are protecting their diplomas, they are not protecting the profession. They are protecting the kind of training they got: because I am a state registered nurse, I have to make sure that state registered nursing stays on the market; because I did HND, let me protect HND. No!' (Int9:3)

Some nurses were perceived to align with their preferred educational model, instead of seeking the best for the profession.

Status conflicts

Conflicts were raised about professional membership. Some professional associations accepted only MOH diplomas:

'The prerequisite to register in the association is a diploma in your profession of 3 years' consecutive training, academic training.' (Int8:1)

'You're A-levels and you go and start doing a degree course when you have not yet been a professional. There is a jump . it shows in the field. And that is why we are not registering them.' (Int8:2)

BSc graduates are registered only if they completed a MOH 3-year diploma programme prior to their BSc studies.

When it came to recruitment of nurses, the MoH was perceived to recruit HE graduates only reluctantly :

' They are not willing to let go at the basic training level . But you are hiring their products with mixed feelings, and there are many out there who have not been hired because of the same reason.' (Int7:4)

The MOH thus preferred its own graduates, and only recruited graduates from other ministries reluctantly.

Another source of conflict was the 'nurse' title. Some nurses thought it was being abused:

'You see that you will train as an auxiliary for 6 months or 9 months - I am a nurse, for what? Eighteen months I am a nurse; this this this - I am a nurse.' (Int3:3)

'Nurse' was used indiscriminately, even by nursing assistant graduates. So some nurses thought it was time to redefine their status:

'You need to redefine a nurse in this country . we need to now ask ourselves what a nurse should do . what training, then we need to go into the curriculum documents . ask ourselves whether it is going to give us that nurse that we want.' (Int9:2c)

A new definition will lead to restructuring of nursing curricula to achieve the envisaged status/ competence.

Discussion

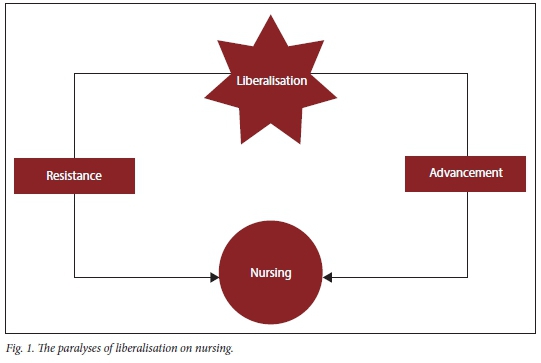

As Fig. 1 indicates, government's liberalisation policy was unprecedented and unanticipated. The fallout from the policy pulled nursing in different directions.

Resistance and advancement

Liberalisation radically changed the educational context, giving rise to PHEIs, and non-nurses became proprietors of nursing schools. These players were perceived to be more profit-oriented than nursing values-oriented. The accompanying curricular diversity upended the MOH national curriculum model, creating the perception of PHEIs running independent programmes. With the MOH's loss of monopoly and the lack of co-ordination between the ministries, nurse education policy was not harmonised. This manifested in diploma upgrade, employment, and professional membership conflicts. The diploma-Bachelor's upgrade conflicts have increased job security anxieties, as some MOH diploma nurses fear competition from incoming degree holders. This has caused some nurses to resist liberalisation-generated changes.

Other nurses have embraced the ongoing changes, and were excited about the opportunity to obtain degrees. The diversity in programmes/ schools has increased access since the time when the MOH trained only for its own needs. PHEIs have created diploma-to-BSc upgrade models for MOH diploma holders. These pathways do not exist in state universities.

The interaction of these forces bears similarities to Lewin's[16] theory of planned change.[12] The change theory is characterised by unfreezing, change and refreeze.[17] According to Maboh,[12] the current context and changes taking place mirror the 'unfreezing' and 'change' phases. However, the key difference is that the ongoing change is unplanned and unco-ordinated. Resistance within nursing makes it difficult for 'refreezing' to be achieved. Comparing liberalisation to Traynor and Rafferty's[18] 'context, convergence and contingency' argument, the context is right for change, while convergence and contingency have been achieved for only one-half of the nursing profession. Thus, change cannot be maximised.

Liberating paralysis and practice implications

Liberating paralysis describes the current context, where unco-ordinated change is concurrently both advancing nurse education and generating resistance that is pulling it backward. This context has resulted from unprecedented change in overall government policy, with unanticipated ripple effects on the profession. These effects ushered in much-needed changes in this time and context. However, this needed change is so disruptive that it has generated significant resistance from some nurses, creating a whirlwind scenario that fails to fully advance nursing education. The absence of a strong national grouping makes it impossible for nursing to take control of the current context. Therefore the profession must organise itself, and develop strategies to influence government policy so that it can maximise situations where government policy provides opportunity for growth. Without this, enabling opportunities will always result in liberating paralysis.

Conclusion

Liberalisation opened HE to the private sector in Cameroon. Divided, the nursing profession both embraced expansion of its educational system into HE and resisted the changes at the same time. The interaction of these opposing forces, without co-ordination from organised nursing, has resulted in a state of liberating paralysis. Further research should explore strategies that prepare professions to anticipate and maximise government policy changes.

Declaration. This study was conducted as part of a PhD degree in Nursing Studies at the University of Essex, UK.

Acknowledgements. Prof. Peter J Martin and Ms Susan Stallabrass, both of the University of Essex, UK, for supervising the overall study on nursing education in Cameroon as part of PhD studies.

Author contributions. Sole author.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Maier C, Aiken L. Expanding clinical roles for nurses to realign the global health workforce with population needs: A commentary. Isr J Health Policy Res 2016;5(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-016-0079-2 [ Links ]

2. Rafferty AM. Nurses as change agents for a better future in health care: The politics of drift and dilution. Health Econ Policy 2018;13(3-4):475-491. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133117000482 [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. Nurses and Midwives: A Vital Resource for Health - European Compendium of Good Practices in Nursing and Midwifery towards Health 2020 Goals. Geneva: WHO, 2015. http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0004/287356/Nurses-midwives-Vital-Resource-Hedth-Compendium.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 26 April 2020). [ Links ]

4. Hall-Long B. Nursing and public policy: A tool for excellence in education, practice, and research. Nursing Outlook 2009;57(2):78-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2009.01.002 [ Links ]

5. Toofany S. Nurses and health policy: Swaleh Toofany asks how nurses can influence health policy in the new political environment following the election. Nurs Manag 2005;12(3):26-30. [ Links ]

6. Cheraghi MA, Ghiyasvandian S, Aarabi A. Iranian nurses' status in policymaking for nursing in health system: A qualitative content analysis. Open Nurs J 2015;9:15-24. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874434601509010015 [ Links ]

7. Ellenbecker CH, Fawcett J, Jones EJ, et al. A staged approach to educating nurses in health policy. Policy Politics Nurs Pract 2017;18(1):44-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154417709254 [ Links ]

8. Braveman P, Egerter S. Overcoming obstacles to health. Report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Commission to Build a Healthier America. Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2008. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2008/02/overcoming-obstacles-to-health.html [ Links ]

9. Ressler P, Glazer G. Legislative nursing's engagement in health policy and healthcare through social media. Online J Issues Nurs 2010;16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01LegCol01 [ Links ]

10. Fyffe T. Nursing shaping and influencing health and social care policy. J Nurs Manag 2009;17(6):698-706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00946.x [ Links ]

11. Rafferty AM, Traynor M. Context, convergence and contingency: Political leadership for nursing. J Nurs Manag 2004;12(4):258-265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00481.x [ Links ]

12. Maboh M. Nursing education in Cameroon: A grounded analysis on seizing the opportunity of the moment. PhD thesis. Colchester: University of Essex, 2016. [ Links ]

13. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage, 2006. [ Links ]

14. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Adeline, 1967. [ Links ]

15. Rapley P, Nathan P, Davidson L. EN to RN: The transition experience pre- and post-graduation. Rural and Remote Health 2006;6:363. [ Links ]

16. Lewin K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers New York: Harpers, 1951. [ Links ]

17. Swanson D, Creed A. Sharpening the focus of force field analysis. J Change Manag 2013;14(1):28-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.788052 [ Links ]

18. Traynor M, Rafferty AM. Nurse education in an international context: The contribution of contingency. Int J Nurs Studies 1999;36(1):85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7489(98)00061-3 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M NMaboh

maboh@hrfbuea.org

Accepted 17 July 2020