Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Health Professions Education

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 no.3 Pretoria Out. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2020.v12i3.1373

RESEARCH

The influence of context on the teaching and learning of undergraduate nursing students: A scoping review

R MeyerI; S C van SchalkwykII; E ArcherII

IRN, RM, MPhil Health Sciences Education, BA Cur (Education and Management), Dip Operating Room Technique; Centre for Health Professions Education, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

IIPhD; Centre for Health Professions Education, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. The role that context plays in the teaching and learning space has been well documented.

OBJECTIVES. To synthesise perspectives from previous studies related to the influence of context on teaching and learning among undergraduate nursing students.

METHODS. This study was guided by the stages for review proposed by Arksey and O'Malley. Six databases were searched, generating 1 164 articles. Based on the eligibility criteria, the articles were screened through several processes, resulting in 55 articles being included in the final review.

RESULTS. Five themes were identified, including the organisational space, the nature of interactions in the healthcare team, the role of the nurse manager, the role of the educator and the academic institution-hospital engagement.

CONCLUSION. While there are many studies of the role of context in teaching and learning, this review highlights the interconnectedness of the various factors within the learning context, providing a framework that can inform decision-making when seeking to enhance teaching and learning in nursing education.

The role that context plays in the teaching and learning space has been well documented, characterised as complex and dynamic, and changing in response to competing international and local demands.[1] This complexity has been recognised in health professions education, with calls for the adaptation of existing curricula that do not adequately equip graduates in the health professions to meet the needs of the communities they serve.[2,3] Understanding the context - the surroundings, circumstances, environments and settings within which learning must occur, particularly when seeking to inform such curriculum renewal processes - is therefore important. Several years ago, Harden[4] argued that an important aspect of curriculum development and renewal is the undertaking of a proper assessment of the learning environment, a dimension of context.

The training of healthcare professionals requires that teaching and learning take place across a range of contexts that extend beyond the traditional classroom, and typically include the clinical space. Researchers in the field have explored context, arguing that this concept extends beyond the physical environment.[5] Its influence has been described as multifaceted, comprising the physical (environmental), semantic (contribution to the learning task) and affective (relating to motivation and responsibility) dimensions.[5] Context in health professions education has been described in terms of the setting, the participants and their interactions,[6] while others view it as six core patterns, including the patient, and the physical, practice, educational, institutional and social contexts.[7]

In the field of nursing education, research exploring context and its influence on the learning experiences of nursing students has also been conducted. Studies have sought to determine the degree to which different entities within the educational context affect the learning experiences of nursing students, including the contribution made by the educator,[8] the type of supervision offered by the manager[9] and the dynamics within the team.[10] Work of other authors points to the psychosocial factors, physical resources and organisational culture within the learning contexts as critical elements influencing learning experiences.[11]

It is evident that there are multiple factors within the educational context that may influence learning experiences, which ought to be considered. In South Africa (SA), nursing education is currently undergoing significant curriculum renewal across its range of undergraduate programmes.[12] Therefore, to better understand how the context influences teaching and learning, specifically among undergraduate nursing students, a scoping review was undertaken.

Methods

Scoping reviews are useful for reviewing and synthesising the available evidence, as well as identifying the 'nature and extent' of research available on a particular topic.[13] This scoping review was guided by the first 5 of 6 stages for review proposed by Arksey and O'Malley,[13] which include identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting the studies for inclusion, charting the data, collating, summarising and reporting results, and consultation.

The research team determined the purpose and steps of the review and research questions were identified. The agreed aim of this review was to synthesise perspectives from previous studies related to the influence of context on the teaching and learning experience of undergraduate nursing students. To inform this (step 1), one broad question was decided on for the scoping review: How does the context influence the teaching and learning of undergraduate nursing students?

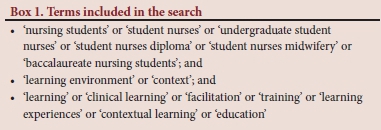

The search was conducted widely to identify relevant studies (step 2) related to the topic. Six databases were included, i.e. CINAHL, ERIC (EBSCOhost), MEDLINE, ProQuest, Google Scholar and Web of Science. The search commenced in May 2018 (step 3), guided by specific inclusion criteria as determined by the research team. Data were collected from literature published from January 2008 to June 2018 to capture the more recent work in this area. All study designs were considered, including quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. This review also considered empirical and secondary studies, e.g. reviews and conceptual articles. Finally, only those articles published in English were examined. In consultation with a librarian, a set of search terms was agreed on (Box 1).

Using the prespecified terms and criteria, the initial search yielded a total of 1 164 articles (step 4). After 17 duplicate articles were removed, the title and abstract of the papers were reviewed against the inclusion criteria, resulting in a total of 183 articles. Abstracts were rejected for two main reasons: when reference was made to students other than nursing students, and/or when there was no reference to the learning context. The full texts of the selected papers were entered into a database and reviewed by one of the authors, at which point all articles not applicable to undergraduate nursing students were excluded, resulting in a total of 55 articles eligible for full analysis (Fig. 1).

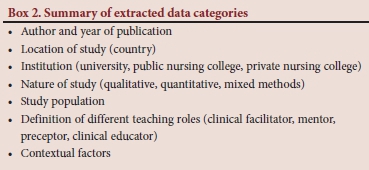

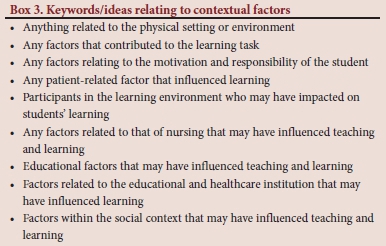

Data were extracted from the included articles and entered into the data extraction sheet in Excel (Microsoft, USA) (step 5) (Box 2) (detailed list -Addendum A (http://ajhpe.org.za/public/files/1373.doc)). This analysis was guided by the main question and keywords/ideas (Box 3), based on the earlier perspectives of Koens et al.,[6] Durning et al[5] and Bates and Ellaway,[7] which informed the theoretical framework for this study.

The first stage of the content analysis involved one of the authors familiarising herself with the content. Thereafter, similar concepts were grouped together to generate codes. Similar codes were combined to form themes and sub-themes.[14] These codes, sub-themes and themes were then reviewed by the co-authors. To further enhance the trustworthiness of the study, an experienced senior research assistant independently analysed the data. The two analyses were then compared to identify similarities and discrepancies that were resolved through further discussions and consensus. In addition to the abovementioned steps, an audit trail was kept by clearly documenting steps taken throughout the review.[15]

According to Arksey and O'Malley,[13] consultation with stakeholders regarding the findings of the scoping review is an optional step that could be included. However, this step was not utilised for this review.

Results

Of the 55 articles eligible for review, 23 used qualitative study designs, 14 used quantitative study designs, 7 used mixed methodology, 8 were reviews, 1 was presented as a conference paper, 1 was a conceptual paper and 1 was an editorial. The 8 review articles focused on specific aspects of context, e.g. factors affecting the adoption of deep approaches to learning,[16] factors affecting readiness to practice,[17] and the influence of sociocultural factors on perceptions of learning.[18] This review adopted an overarching approach seeking to explore all aspects within the learning context that may have influenced teaching and learning.

Forty-four articles described empirical studies mostly conducted at universities. However, a small percentage (19%) was conducted at public nursing schools and private nursing schools, representing the traditional range of nursing institutions. Studies reported in publications were conducted in 19 countries, with Australia, the UK and the USA contributing more than half of the included studies (n=28). Thirty-six studies examined the influence of contextual factors on learning from the perspective of students, 1 article from the perspective of the head of the school,[19] 1 from the perspective of educators and students,[20] another from the perspective of supervising nurses and students, and 5 from the perspective of qualified nurses in the ward and students.

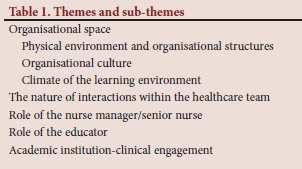

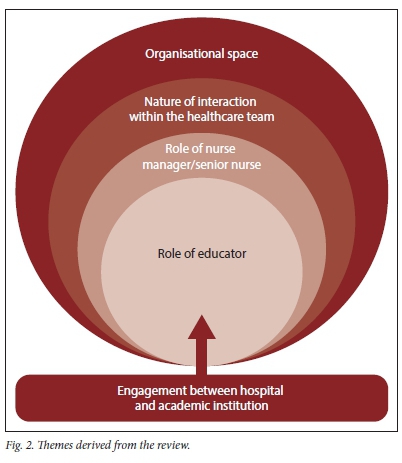

Five themes were identified from this review (Table 1), which frame the context within which teaching and learning of undergraduate nurses take place, including the organisational space, the nature of interactions within the healthcare team, the role of the nurse manager/senior nurse, the role of the educator, and the academic institution-hospital engagement. These five themes represent components of context that influence the way teaching and learning experiences were perceived by the various participants in the included studies (Addendum A (http://ajhpe.org.za/public/files/1373.doc)). While the findings below are presented according to themes, there is a high degree of integration between them, resulting in some overlap.

Organisational space

The organisational space, i.e. the place where the training of nurses was undertaken, was one of the most dominant themes across the included studies. It comprises three sub-themes, i.e. the physical environment and organisational structures within the institution, the organisational culture, and the organisational climate within the learning environment.

Physical environment and organisational structures

This sub-theme relates to all the structural issues - the ways in which the parts of a system are arranged - that may influence the creation of an environment conducive to learning. Physical factors that negatively influenced learning experiences included large class sizes[21] and lack of restrooms, facilities, space, equipment and learning tools.[11,22-25] A specific physical aspect that improved learning experiences was the availability of infrastructure to enable the use of technology in teaching and learning.[26-28]

One of the factors related to organisational structures that negatively influenced learning experiences was insufficient staffing in the clinical areas, resulting in higher workloads for the students engaged with workplace-based learning, who were expected to fulfil more tasks than might have been expected of them in more fully staffed environments.[25,29-31] Outcomes of these higher patient workloads for students included increased stress,[29,30] emotional and physical burnout[31] and 'superficial learning', reducing satisfaction with the learning environment.[25] Insufficient staffing and increased stress also influenced the dynamics within the healthcare team and the extent to which educators were able to provide support owing to less time allocated for teaching.[32,33]

Some studies revealed that students had a positive experience when the context enabled exposure to variable learning opportunities specific to their level of training.[20,34] Students also indicated that a longer duration of clinical placement increased their exposure to learning opportunities,[20,32,34,35] while sufficient time for clinical teaching and learning allowed the opportunity to develop clinical skills and consolidate knowledge.[10,32,35] This issue is addressed below.

Another aspect related to organisational structures was the presence of social hierarchies.[31] These hierarchies, which are based on age, work experience and job titles, seem to have negatively influenced learning experiences, as students indicated that they felt positioned at the bottom of the hierarchy.

Organisational culture

Culture is seen to reside in the ideas, norms, values and customs of a particular context.[36] According to some of the included articles, an organisational culture that promotes learning includes aspects such as the organisation's

perception of nursing education as a valuable entity,[35] leadership styles that promote quality learning experiences,[11] the manager's positive attitude towards education,[33] and organisational policies that support teaching, learning and supervision.[11,22,37] Low levels of organisational support, e.g. not recognising the role of informal teaching as an inherent function of experienced nurses, seemed to be another recurring theme.[11,22,25,32] It was argued that these factors reflected a culture that did not support teaching and learning.[38]

Denison[39] distinguishes between organisational climate and culture, referring to climate as 'a situation and its link to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of organisational members'. Flott and Linden[11] suggest that organisational culture influences organisational climate, where an organisation that values education has a positive climate and vice versa. Therefore, although both concepts are interrelated, they will be discussed separately.

Climate of the learning environment

In the included studies, climate was linked to a sense of belonging within a team, influenced by the nature of interactions. Being welcomed by the staff created a positive climate, which contributed to a positive learning environment,[10,40-43] one that specifically supported learning.[10,42,43] Factors creating a negative climate included unfriendliness, stress and fatigue among staff.[18,31,33,44] Although it might seem that an enabling climate is an essential contributor to the learning environment, one study found that students rated the ward climate less important to learning than the role of the educator.[45] However, this finding was ascribed to students being taught by various members in the healthcare team, and that they were possibly dissatisfied with the lack of a designated educator. This issue will be discussed below (see: Role of the educator).

The nature of interactions within the healthcare team

Creating an environment conducive to learning requires support and recognition from fellow senior students, ward staff, senior nurses, medical personnel and managers. Support from fellow senior students and peers reduced the feeling of isolation for some students,[18,24,46] while a positive attitude towards learning by other students and staff in the unit (the team) enhanced learning experiences.[20,37,47,48] Other positive aspects relating to the healthcare team included being recognised as a team member,[10,37,45,49] receiving acknowledgement from medical personnel,[48] being recognised as autonomous practitioners within the team,[10,36,38,46] experiencing mutual respect, good communication and positive interactions with team members.[10,11,46,50-52] Aspects related to this theme that served as barriers included students feeling unwanted by and a hindrance to senior nurses,[10,47] and sensing that other medical personnel and/or their colleagues did not respect them[53] or have confidence in their ability to perform certain skills.[42]

Role of the nurse manager/senior nurse

Supervision in health professions education often refers to a wide range of activities. In the context of this review, however, supervision encompasses managing the work performance of the nursing team, including the student, as well as offering clinical teaching.[20,33,54]

The included studies revealed that support offered through supervision is perceived as an important component of the context that influences students' learning experiences.[8,33,34] The ward manager and senior nurses were perceived as central to creating an environment conducive to learning through effective management and supervision in the clinical environ-ment.[8,33,37,53] Aspects such as availability of the manager to teach,[55] and a positive supervisory relationship between the manager and the student,[18] were perceived as factors that promoted learning. Although satisfaction with the amount of exposure students received was influenced by the role of the educator, it was clear that organisational support and the role of the nurse manager/senior nurse invariably influenced the time allocated to formal clinical teaching and learning[33,38,48] as mentioned above (see: Physical environment and organisational structures; and Organisational culture). A negative aspect highlighted in two of the included studies as an obstacle to effective learning experiences was when the nurse manager or senior nurses were perceived as being unaware of learning objectives, with minimal consideration for encouraging student independence.[33,56]

Role of the educator

This theme focuses on those specifically appointed to the teaching role. The importance of distinguishing between the various role-players involved in the teaching of students in the clinical environment was highlighted.[57-59] Although there are different role-players involved in the teaching/supervision of students, most of the studies that refer to this theme did not provide clear definitions or distinguishing features of the roles of mentors, preceptors, clinical facilitators and clinical educators. Nevertheless, many articles pointed to the importance of the educator role, as preceptor or mentor in preparing the environment for teaching and learning.[8,10,45]

Key factors that seemed to have enabled learning included a higher level of educator competence in terms of teaching ability,[44] the allocation of students to a designated educator, as described above (see: Climate of the learning environment),[9,33,43,45] frequent contact with educators,[34] and constructive relationships between students and educators.[8,22,43] Inevitably, the converse of these situations often tended to negatively influence learning, such as the lack of preparedness for teaching sessions by educators,[48] the allocation of different educators, or the absence of a designated educator during clinical placement.[30] Furthermore, a lack of congruence between student and educator expectations,[29] poor mentorship,[44] limited support by educators in achieving learning objectives,[53,60] a lack of feedback[40] and negative attitudes of educators towards students[25] constrained effective learning experiences.

Academic institution: Hospital engagement

The nature of nursing education typically implies a relationship between an academic institution and a hospital. Although not dominant across the included studies, it was evident that this relationship had an influence on the learning culture in the clinical learning environment. Engagement between role-players occurs in different contexts: institutionally, in the clinical space, in the classroom and interpersonally. Some of the included studies also revealed that an enabling environment is premised on meaningful engagement between the academic institution and the clinical learning environment.[37,43,61,62] For example, learning experiences were perceived as positive when there was better co-operation between academic and ward staff,[37,43,61,62] as this fostered a more positive climate in which learning could take place.[62] Poor co-operation resulted in frustrated students, creating a negative learning experience.[53,61,62] Moreover, poor interpersonal relationships between academic staff and ward staff caused confusion and limited the opportunities for ward staff and nurse managers to assist students in meeting their learning objectives.[61]

Summary

The organisational space seems to have shaped the teaching and learning context by influencing all other contextual influences presented in this review. Furthermore, it is evident that the other contextual factors in the included articles have varying degrees of influence on each other, as well as the organisational space. Fig. 2 provides a visual perspective of the interrelatedness of the various themes.

Discussion

This review confirms that context is indeed a complex concept,[7] encompassing multiple components that interact with one another in different ways and across different levels. However, this review also offers a framework (Fig. 2) to better understand this complexity. It is clear that the way in which context influences teaching and learning is best understood across structural, cultural and interpersonal domains, as discussed below.

It is evident that the organisational space has a major influence on the way teaching and learning takes place within a healthcare institution. Therefore, those responsible for developing nursing curricula need to be mindful of the challenges and affordances that are available within the organisational space and then plan accordingly. Furthermore, this framework posits that the relationship between the academic institution and hospital sets the tone for the way in which the organisational climate and culture are established. This culture and climate permeate the various interactions that a nursing student is exposed to, whether in the clinical domain or in the classroom. A proper assessment of the dynamics within the context through its influence on teaching and learning is therefore essential when seeking to improve teaching, learning and curriculum renewal.[4]

Findings from this review suggest the presence of multiple sources of teaching, both formal and informal, by various role-players in the clinical environment, affirming the complexity of nursing education. These role-players form an integral part of the context, influencing students' learning experiences in varying degrees.[37,43,61,62] To achieve synergy among the role-players, it is necessary to acknowledge the contributions of these individuals, including the academic staff, educators in the clinical environment, the healthcare team and nurse managers.

What seems to be absent in this review is the distinct role of the patient as a contextual factor in the learning environment. This is in contrast to what Bates and Ellaway[7] found in their scoping review, which points to patient characteristics as a recurring theme in their included articles. Finally, the role of the student, who is central to the discussion on teaching and learning, did not seem to feature in any of the reviewed articles. If we consider what Norman and Schmidt[64] said when they claimed that 'the context includes all features of the environment at the time of learning ...', which is still relevant to current health professions education, then in a clinical learning context, the essential role of the patient and student and its influence on teaching and learning must be considered.

There are a number of limitations that must be kept in mind when reading the results of this review. Some relevant articles may have been unintentionally excluded owing to the inclusion of only articles published in English, in scientific journals, and from 2008 to 2018. In addition, the quality of the articles included in this review was not formally appraised,[13] as the intention of this scoping review was to provide a description of what was available on the topic. Furthermore, while a research assistant provided some sample checking, one of the authors (RM) was predominantly responsible for populating the data extraction sheet.

Conclusion

The learning context as an integral part of teaching, learning and curriculum renewal is currently receiving increased attention. Although there have been many studies on the role of context in teaching and learning, this review highlights the interconnectedness of the various factors within the learning context. Given the current transitions in nursing education, we argue that further research into the influence of context is needed, especially for those seeking to enhance teaching and learning across all spheres (clinical and classroom).

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors acknowledge the contribution made by Ilse Meyer, who conducted an additional data extraction and analysis for comparison.

Author contributions. RM, SCvS, EA: conception and design of the study; RM, SCvS, EA: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; RM: drafting the article; SCvS, EA: revising the article critically for important intellectual content; SCvS, EA, RM: final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Bitzer E. Inquiring the curriculum in higher education. In: Bitzer E, Botha N, eds. Scholarly Curriculum Enquiry in South African Higher Education: Some Affirmations and Challenges. Stellenbosch: Sun Media, 2011:33-53. [ Links ]

2. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376(9756):1923-1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61854-5 [ Links ]

3. Tanner CA. Transforming prelicensure nursing education: Preparing the new nurse to meet emerging health care needs. Nurs Educ Perspect 2010;31(6):347-353. [ Links ]

4. Harden R. Ten questions to ask when planning a course or curriculum. Med Educ 1986;20(4):356-365. [ Links ]

5. Koens F, Mann KM, Custers EJ, ten Cate OT. Analysing the concept of context in medical education. Med Educ 2005;39:1243-1249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02338.x [ Links ]

6. Durning SJ, Artino AR, Pangaro LN, van der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L. Redefining context in the clinical encounter: Implications for research and training in medical education. Med Educ 2010;85(5):894-901. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181d7427c [ Links ]

7. Bates J, Ellaway RH. Mapping the dark matter of context: A conceptual scoping review. Med Educ 2016;50(8):807-816. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13034 [ Links ]

8. Carlson E, Idvall E. Nursing students' experiences of the clinical learning environment in nursing homes: A questionnaire study using the CLES+T evaluation scale. Nurse Educ Today 2014;34(7):1130-1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.01.009 [ Links ]

9. Sundler AJ, Bjork M, Bisholt B, Ohlsson U, Engstrom AK, Gustafsson M. Student nurses' experiences of the clinical learning environment in relation to the organization of supervision: A questionnaire survey. Nurse Educ Today 2013;34(4):661-666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.06.023 [ Links ]

10. Ford K, Courtney-Prat H, Marlow A, Cooper J, Williams D, Mason R. Quality clinical placements: The perspectives of undergraduate nursing students and their supervising nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2016;37:97-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.11.013 [ Links ]

11. Flott A, Linden L. The clinical learning environment in nursing education: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2016;72(3):501-513. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12861 [ Links ]

12. National Department of Health. The National Strategic Plan for Nurse Education, Training and Practice 2012/2013 - 2016/2017. Pretoria: NDoH, 2013. [ Links ]

13. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Inter J Soc Res Method 2005;8(1):19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ Links ]

14. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15(3):398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048 [ Links ]

15. Frambach JM, van der Vleuten CPM, Durning SJ. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Acad Med 2013;88(4):552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f [ Links ]

16. Baeten M, Kyndt E, Struyven K, Dochy F. Using student-centred learning environments to stimulate deep approaches to learning: Factors encouraging or discouraging their effectiveness. Educ Rev Res 2010;5(3):243-260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.06.001 [ Links ]

17. Edward K, Ousey K, Playle J, Giandinoto J. Are new nurses work ready - the impact ofpreceptorship: An integrative systematic review. J Prof Nurs 2017;33(5):326-333. https://doLorg/10.1016/j.profcurs.2017.03.003 [ Links ]

18. Jessee MA. Influences of sociocultural factors within the clinical learning environment of students' perceptions of learning: An integrative review. J Prof Nurs 2016;32(6):463-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.03.006 [ Links ]

19. Mulder M, Uys LR. Baseline measurement of the implementation process of the proposed model for clinical nursing education and training in South African universities. Trends Nurs 2012;1(1):1-24. https://doi.org/10.14804/1-1-24 [ Links ]

20. Chuan OL, Barnett T. Student, tutor, and staff nurse perceptions of the clinical learning environment. Nurse Educ Pract 2012b;12:192-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2012.01.003 [ Links ]

21. Lee S, Sasser J. Nursing students' perceptions of class size and its impact on test performance: A pilot study. J Nurs Educ 2011;50(12):715-718. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20111017-05 [ Links ]

22. Haraldseid C, Friberg F, Aase K. Nursing students' perceptions of factors influencing their learning environment in a clinical skills laboratory: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(9):e1-e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.03.015 [ Links ]

23. Ndawo MG. Lived experiences of nurse educators on teaching in large class at a nursing college in Gauteng. Curationis 2016;39(1):a1507. https://doi.org/10.4102%2Fcurationis.v39i1.1507 [ Links ]

24. Sercekus P, Baskale H. Nursing students' perceptions about clinical learning environment in Turkey. Nurse Educ Pract 2016;17:134-138. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.nepr.2015.12.008 [ Links ]

25. Tharani A, Husain Y, Warwick I. Learning environment and emotional well-being: A qualitative study of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2017;59:82-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.008 [ Links ]

26. McCutcheon K, Lohan M, Traynor M, Martin D. A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face-to-face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. J Adv Nurs 2014;71(20):255-270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12509 [ Links ]

27. Vogt M, Schaffner B, Ribar A, Chavez R. The impact ofpodcasting on the learning and satisfaction of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract 2010;10:38-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2009.03.006 [ Links ]

28. Moule P, Ward R, Lockyer L. Nursing and healthcare students' experiences and use of e-learning in higher education. J Adv Nurs 2010;66(12):2785-2795. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05453.x [ Links ]

29. Al-Zayyat AS, Al-Camal E. Perceived stress and coping strategies among Jordanian nursing students during clinical practice in psychiatric/mental health care courses. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2014;23(4):326-335. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12054 [ Links ]

30. Blomberg K, Bisholt B, Engstrom AK, Ohlsson U, Johansson AS, Gustafsson M. Swedish nursing students' experience of stress during clinical practice in relation to clinical setting characteristics and the organisation of the clinical education. J Clin Nurs 2014;23(15-16)2264-2271. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12506 [ Links ]

31. Jae Lee J, Clarke CL, Carson MN. Nursing students' learning dynamics and influencing factors in clinical contexts. Nurse Educ Pract 2018;29:100-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.12.003 [ Links ]

32. Courtney-Pratt H, Ford K, Marlow A. Evaluating, understanding and improving of quality placements for undergraduate nurses: A practice development approach. Nurse Educ Pract 2015;15(6):512-516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.07.002 [ Links ]

33. Bisholt B, Ohlsson U, Engstrom AK, Johansson S, Gustafsson M. Nursing students' assessment of the learning environment in different clinical settings. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14(3):304-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.11.005 [ Links ]

34. Gurkova E, Ziakova K, Cibrikova S, Magurova D, Hudakova A, Mroskova S. Factors influencing the effectiveness of clinical learning environment in nursing education. Centr Eur J Nurs Midwifery 2016;7(3):470-475. https://doi.org/10.15452/CEJNM.2016.07.0017 [ Links ]

35. Peters K, McInnes S, Halcomb E. Nursing students' experiences of clinical placement in community settings: A qualitative study. Collegian 2015;22(2):175-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2015.03.001 [ Links ]

36. Wong AK. Culture in medical education: Comparing a Thai and a Canadian residency programme. Med Educ 2011;45(12):1209-1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04059.x [ Links ]

37. D'Souza MS, Karkada SN, Parahoo K, Venkatesaperumal, R. Perception of and satisfaction with the clinical learning environment among nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(6):833-840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.02.005 [ Links ]

38. O'Mara LO, McDonald J, Gillespie M, Brown H, Miles L. Challenging clinical learning environments: Experiences of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14(2):208-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.012 [ Links ]

39. Denison DR. What is the difference between organisational culture and organisational climate? A native's point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. Acad Manag Rev 2016;21(3):619-654. https://doi.org/10.2307/258997 [ Links ]

40. Cheraghi MA, Salasli M, Ahmadi F. Factors influencing the clinical preparation of BS nursing student interns in Iran. Int J Nurs Pract 2008;14(1):26-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172x.2007.00664.x [ Links ]

41. Happell B. Clinical experience in metal health nursing: Determining satisfaction and the influential factors. Nurse Educ Today 2008;28(7):849-855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2008.01.003 [ Links ]

42. Sahay A, Hutchinson M, East L. Exploring the influence of workplace supports and relationships on safe medication practice: A pilot study of Australian graduate nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(5):e21-e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.01.012 [ Links ]

43. McCara-Couper J, Gilkison A, Fielder AN, Donald H. A mixed-method evaluation of a New Zealand based midwifery education development unit. Nurse Educ Pract 2017;25:57-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.05.002 [ Links ]

44. Baglin MR, Rugg S. Student nurses' experiences of community-based practice placement learning: A qualitative exploration. Nurse Educ Pract 2010;10(3):144-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2009.05.008 [ Links ]

45. Papastavrou E, Lambrinou E, Tsangari H, Saarikoski M, Leino-Kilpi H. Student nurses experience of learning in the clinical environment. Nurse Educ Pract 2010;10:176-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2009.07.003 [ Links ]

46. Christiansen A, Bell A. Peer learning partnerships: Exploring the experience of pre-registration nursing students. J Clin Nurs 2010;19(5-6):803-810. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02981.x [ Links ]

47. Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J, Higgins I, McMillan M. Staff-student relationships and their impact on nursing students' belongingness and learning. J Adv Nurs 2009;65(2):316-324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04865.x [ Links ]

48. Meyer R, van Schalkwyk SC, Prakaschandra R. The operating room as a clinical learning environment: An exploratory study. Nurse Educ Pract 2016;18:60-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.03.005 [ Links ]

49. Papathanasiou IV, Tsaras K, Sarafis P. Views and perceptions of nursing students on their clinical learning environment: Teaching and learning. Nurse Educ Today 2014;34(1):57-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.02.007 [ Links ]

50. Ludin SM, Fathullah NMN. Undergraduate nursing students' perceptions of the effectiveness of teaching behaviours in Malaysia: A cross-sectional, correlational survey. Nurse Educ Today 2016;44:79-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.05.007 [ Links ]

51. Walker S, Rossi D, Anastasi J, Gray-Ganter G, Tennent, R. Indicators of undergraduate nursing students' satisfaction with their learning journey: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Today 2016;43:40-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.04.011 [ Links ]

52. Wallin K, Fridlund B, Thoren A. Prehospital emergency nursing students' experiences of learning during prehospital clinical placements. Int Emerg Nurs 2013;21(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2012.09.003 [ Links ]

53. Hamshire C, Willgoss TG, Wibberley C. 'The placement was probably the tipping point' - the narratives of recently discontinued students. Nurse Educ Pract 2012;12(4):182-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.11.004 [ Links ]

54. Hooven K. Nursing students' qualitative experiences in the medical-surgical clinical learning environment: A cross-cultural integrative review. J Nurs Educ 2015;14(8):421-428. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20150717-01 [ Links ]

55. Rebeiro G, Edward K, Chapman R, Evans A. Interpersonal relationships between registered nurses and student nurses in the clinical setting - a systematic integrative review. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(12):1206-1211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.06.012 [ Links ]

56. Melincavage SM. Student nurses' experiences of anxiety in the clinical setting. Nurse Educ Today 2011;31:785-789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.05.007 [ Links ]

57. Mills JE, Francis KL, Bonner A. Mentoring, clinical supervision and preceptoring Clarifying the conceptual definitions for Australian rural nurses. A literature review. Rural Remote Health 2005;5(3):410-419. [ Links ]

58. Bray L, Nettleton P. Assessor or mentor? Role confusion in professional education. Nurse Educ Today 2007;27:848-855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.11.006 [ Links ]

59. Holland K, Lauder W. A review of evidence for the practice learning environment: Enhancing the context for nursing and midwifery care in Scotland. Nurse Educ Pract 2012;12(1):60-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.05.008 [ Links ]

60. Salamonson Y, Everett B, Halcomb E, et al. Unravelling the complexities of nursing students' feedback on the clinical learning environment: A mixed methods approach. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(1):205-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.08.005 [ Links ]

61. Mabuda BT, Potgieter E, Alberts UU. Student nurses' experience during clinical practice in the Limpopo Province. Curationis 2008;31(91):19-27. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v31i1.901 [ Links ]

62. Watt E, Pascoe E. An exploration of graduate nurses' perceptions of their preparedness for practice after undertaking the final year of their bachelor of nursing degree in a university-based clinical school. Int J Nurs Pract 2013;19(1):23-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12032 [ Links ]

63. Houghton CE, Casey D, Shaw D, Murphy K. Students' experiences of implementing clinical skills in the real world of practice. J Nurs Pract 2012;22(13-14):1961-1969. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12014 [ Links ]

64. Norman GR, Schmidt HG. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: A review of the evidence. Acad Med 1992;67(9):557-565. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199209000-00002 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R Meyer

rhodameyer@sun.ac.za

Accepted 24 June 2020