Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 n.3 Pretoria Oct. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2020.v12i3.1352

RESEARCH

A broken triangle: Students' perceptions regarding the learning of nursing administration in a low-resource setting

B MasavaI; L N BadlanganaII; C N NyoniIII

IBSc Hons Nursing Science, MPhil HPE; Paray School of Nursing, Thaba-Tseka, Lesotho

IIBS, MS, PhD; Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

IIIBSc Hons Nursing Science, MSocSc (Nursing), MHPE, PhD; School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Nursing education institutions (NEIs) must ensure that their graduates are competent in nursing administration. The adoption of nursing administration-related learning outcomes in pre-registration nursing programmes in Africa has created a platform for the teaching and assessment of nursing administration. Challenges aligned with low-resource NEIs, such as rigid content-based vocational programmes, limit the value and utility of the teaching of nursing administration, resulting in graduates who are not able to manage healthcare units effectively. Therefore, this study explored students' experiences of a nursing administration module with the hope that alignment of the outcomes, content and assessments would be pivotal in the module review to improve nurses' efficiency in managing health units.

OBJECTIVES. To describe student nurses' perceptions regarding the alignment of learning outcomes, content and assessment of a nursing administration module in an NEI in a low-resource setting.

METHODS. A sequential mixed methods design was executed in three phases. Data were collected through documents, self-administered questionnaires and focus group discussions with students enrolled in a 3-year pre-registration programme at an NEI in a low-resource setting. The gathered documents were enumerated and mapped against the specific elements of a curriculum as described by Harden and Dent. The quantitative data were analysed through descriptive statistics, focusing on frequencies. The data generated from the focus groups were transcribed verbatim, and thematic analysis through an inductive reasoning approach was used.

RESULTS. The study revealed a non-alignment among learning outcomes, content and assessment of the administration module, causing students to struggle in meeting the expected learning outcomes of the module. In as much as the curriculum documents specified the learning outcomes, the classroom teaching seemed only to be aligned with the described curriculum. In addition to other challenges, the contextual characteristics of the related clinical environment did not support application of what was learnt in the classroom. The assessment practices mirrored the expectations of the curriculum, but were not aligned with contextual realities.

CONCLUSION. Nursing students struggle to meet expected learning outcomes related to nursing administration due to the non-alignment among learning outcomes, content and assessment of the module. NEIs in low-resource settings must radically transform their pre-registration nursing curricula to incorporate contemporary issues and clinical contextual realities to enhance the utility of nursing administration learning outcomes.

Nursing education institutions (NEIs) must ensure that their pre-registration students reflect nursing administration-related competencies at graduation.[1-3] Such competencies include the ability to effectively and efficiently manage human resources,[4,5] reason through complex situations,[6] distribute clinical resources, monitor and evaluate healthcare[3] and communicate effectively.[7] These competencies are pertinent in low-resource settings, which are characterised by critical human resource shortages, lack of staff mentorship programmes and limited resources for on-the-job training in nursing administration, compounded by a greater need for quality healthcare provision.[8]

Numerous NEIs in Africa, guided by regulatory requirements, have included nursing administration-specific learning outcomes in their pre-registration programmes.[2,9,10] This inclusion has necessitated the teaching and assessment of elements of nursing administration at pre-registration level, with the anticipation that graduates from such programmes will effectively manage healthcare units, such as primary healthcare clinics and hospital units.[11] However, the complex clinical environment compromises the quality of teaching, learning and assessment of nursing learning outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa.[8,9]

The majority of the NEIs in Africa offer nursing education through vocational programmes long after the call by the World Health Organization (WHO) to transform health professions education to be competency driven.[8,12,13] Such vocational programmes are presented through teacher-centred, rigid, content-based curricula that are underpinned by behaviourism. Nursing students in typical vocational programmes have a limited amount of class time, but extensive placement in the clinical environment. The latter would be advantageous for students to gain real-life experiences, but poor planning limits the value of the clinical placement to enhance students' nursing administration clinical experience. The staff in the clinical environment perceive nursing students as supernumerary staff, who are expected to shadow professional nurses in practice and even relieve them of their professional duties.[14,15] Consequently, newly graduated nurses struggle to adapt to the nursing administration requirements of the real-world environment, which compromises the quality of health services.[16]

The transition of NEIs from a vocational to a professional educational programme requires a shift in instructional design and teaching of nursing modules, including nursing administration. NEIs in low-resource settings need practical guidance to improve the quality of teaching and learning of nursing administration. We argue that insight in the alignment of the learning outcomes, content and assessment of nursing administration education would inform the design of pre-registration nursing administration programmes. The triangle thus refers to the alignment between learning outcomes, content and assessments. This article reports on an evaluation of aspects of a pre-registration nursing administration module in a low-resource setting in Africa.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate and describe the alignment of learning outcomes, content and assessment of a nursing administration module in an NEI in a low-resource setting.

Methods

Underpinned by pragmatism, this study was executed through sequential mixed methods at an NEI in a low-resource setting in Africa. The NEI included in this study offered a 3-year pre-registration nursing programme guided by a national nursing curriculum that includes a nursing administration module. This module was presented in two sequential components, i.e. a classroom-based theoretical component and a hospital-based practical component, as directed by the national nursing curriculum. The study population comprised final-year nursing students who had completed both components of the nursing administration module. All 40 nursing students were invited and included in the study.

Data were collected in three sequential phases. The initial phase involved the collection of all available documents related to the learning outcomes, content and assessment of the nursing administration module. The authors requested permission from the institution's gatekeepers to use the selected documents for study. The collected documents were de-identified, coded, duplicated and categorised. The second phase was the quantitative strand of the study, where data were collected from the nursing students through self-administered questionnaires. Selected participants gave written consent to participate in the study survey and focus group discussions. The questionnaire was generated by the researchers from reviewing the literature, and explored the nursing students' experiences of the components of the nursing administration module. The third phase was informed by the outcome of the data analysis of the preceding phases and was executed through four focus group discussions with the same population. The first author, who is experienced in conducting interviews and worked at the setting, conducted the focus group discussions with the aid of a research assistant. The discussions were digitally recorded and field notes were collected.

The collected data were analysed using approaches appropriate for each phase. The documents collected were enumerated and mapped against a curriculum model.[17] The quantitative data were analysed through descriptive statistics, focusing on frequencies. The results of the quantitative analysis informed the development of questions for the focus group discussions. The data generated from the focus groups were transcribed verbatim, and thematic analysis through inductive reasoning was applied, guided by principles of qualitative data analysis by Creswell.[18]

The rigour of the study was enhanced by the application of the trustworthiness framework.[19,20] First, the study explicitly explained how the authors collected and analysed data, thereby establishing auditability. Second, the third author verified the data coding and conclusions drawn from thematic analysis. Third, the investigators' interpretations were checked against those of the readily available participants. Fourth, the authors triangulated the data collection methods to validate and corroborate findings obtained during the study.[21]

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health, Lesotho (ref. no. ID08-2017), and the management of the Paray School of Nursing approved the study. The Belmont Report ethics framework of 1979 was applied throughout the design and execution of this study.[22]

Results

The results of this study are presented in the three phases in which the study was executed.

Phase 1: Document analysis

The initial phase was an analysis of documents used in the implementation of the nursing administration module. The gathered documents were enumerated and mapped against the specific elements of a curriculum, as described by Harden et al.[17] The results of document analysis are presented in Table 1.

Phase 2: Quantitative survey

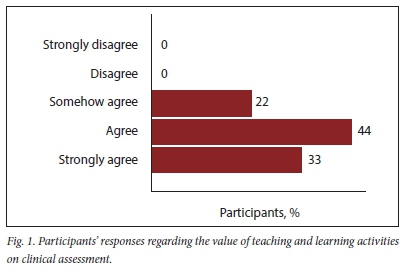

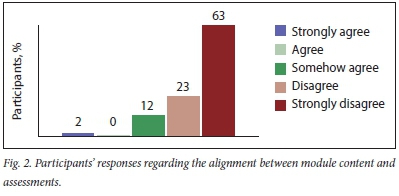

The quantitative survey was structured under three main sections, i.e. learning outcome, content and assessment. Thirty-six of the 40 participants responded to this survey. Fourteen (39%) participants highlighted that the teaching and learning activities were not adequate in preparing them for the real-world setting. The majority (n=23; 65%) stated that they felt incompetent to integrate the content learnt in the classroom into practice during work-integrated learning. Most of the participants (n=28; 77%) valued the teaching and learning activities for assessment (Fig. 1), while 31 (86%) stated that there were differences between real-world nursing administration and written assessments (Fig. 2).

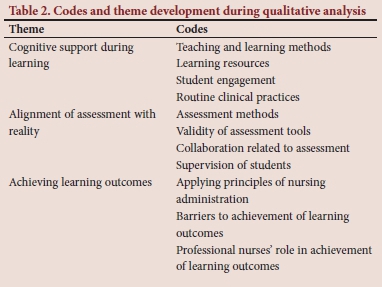

Phase 3: Results of focus group discussions

Three themes emerged from the focus group discussions: cognitive support during learning; alignment of assessment with reality; and achieving learning outcomes (Table 2).

Theme 1: Cognitive support during learning

The participants described various experiences related to cognitive support in the classroom and the clinical environment as they learnt nursing administration. In the classroom setting, the participants indicated that nurse educators taught nursing administration through lectures supported by PowerPoint (Microsoft, USA) presentations. The presented content supported their thinking and understanding regarding nursing administration. However, examples in the prescribed textbooks were focused on foreign or non-native examples, which made it very difficult for the participants to relate to. There were no locally written textbooks for the module and the nurse educators could not translate such examples for the local context. During the classroom activities, there was limited student-to-student interaction, as the educators lectured didactically:

'The educators focus on teaching through the slides, at times they read to you the slides as they are written. We just sit there and take notes, as they may not be willing to share those slides.' (FG2, S2)

Challenges seemed to arise when students were expected to apply principles of nursing administration in practice. Professional nurses in the wards are expected to supervise students as they apply their classroom learning in the clinical setting. However, the professional nurses in the clinical environment had developed routine approaches to administering nursing units, which were not aligned with what the students were taught in the classroom. Compounding this situation, was the unavailability of nurse educators in the clinical environment to support students as they translated their knowledge. Nurse educators only appeared in the clinical environment for assessments:

' The nurses in the wards have no idea about management principles, they have routines and expect us to also follow that routine. The problem is that the routine is not what we have been taught and the teachers are never there to help us or even defend us. We only see them [nurse educators] on the date of the final assessment.' (FG1, S4)

Theme 2: Alignment of assessment with reality

The students' attainment of the learning outcomes was measured through two distinct approaches, i.e. written tests and examinations, and directly observed long case examinations. The written tests and examinations focused on the content taught in class, and the participants described such assessments as fair. However, they indicated that the written tests and assessments were not aligned with the reality in the clinical environment or best practices of nursing administration:

'...I mean the tests are fair, it's just the stuff we learnt in class. You cram and regurgitate it and you are fine, but you know you will never see half of that anywhere in this country. But you do that to please the teacher and pass.' (FG3, S5)

Challenges related to clinical assessment seemed to emanate from assessment tools that were not informed or inspired by the clinical environment or best practices in nursing administration. The participants conveyed that the assessors seemed to be following a much earlier standard checklist that was not flexible to accommodate the contextual realities of the clinical setting. According to the participants, this checklist contributed to their perceived poor performance in their clinical assessment in nursing administration:

' I would have passed management [nursing administration] with high marks, but they assess us with an old checklist, which does not adapt to what is happening in the clinical area. The clinical areas in this place are very different from what the checklist is asking us to do.' (FG1, S2)

The students further explained that there was limited collaboration and poor co-ordination between the clinical nursing staff and NEIs. The students expressed the opinion that there seemed to be poor communication and they often felt lost in the clinical environment when asked to engage in activities not aligned with the stated learning objectives. Even then there was minimal supervision regarding these objectives in the clinical setting:

'Our teachers ... they just give you a schedule of which ward you will go to and a couple of objectives and that's it. The nurses have no time for those objectives and they will send you throughout the hospital. By the time of the assessment, you have no idea what you are doing.' (FG4, S1)

Theme 3: Achieving learning outcomes

The learning outcomes of the nursing administration module expected students to be able to apply the principles and theories of nursing administration in the management of a healthcare unit. The participants revealed several barriers that influenced their attainment of the intended learning outcomes. These barriers were compounded by organisational culture and traditions, which were described as norms or routines. Such routines were not aligned with best practices and challenged the participants in achieving their learning outcomes:

'We wonder at times if those nurses were trained through the same programme. We always seem to speak a different language when it comes to management and they are stuck in their ways even when it doesn't work.' (FG2, S4)

The learning outcomes attained during the clinical practices were informed by what the professional nurse expected from the students in the clinical setting; these outcomes were not necessarily aligned with the curriculum requirements. The participants verbalised that these nurses viewed them as an additional pair of hands and not necessarily as students.

Discussion

This study describes the alignment of learning outcomes, teaching strategies, content and assessment associated with a nursing administration module at a resource-limited NEI. The learning outcomes, content, teaching strategies, especially the learning environment and assessments, need to be coherent to enhance learning among students.[23,24] The metaphor of a broken triangle reflects a summary of the outcome of this study, as elements of the design and implementation of the nursing administration module were not aligned and therefore compromised student learning.[25]

The learning outcomes are aimed at producing a nurse who is able to manage a healthcare unit effectively. The assessment processes in the classroom and clinical environments are aimed at assisting nurse educators in determining if the students meet the learning outcomes.[26,27] In this study, it is clear that assessment practices are aligned with the expectations of the described curriculum, but are not sensitive to context. Assessment methods and the content of assessment tools need to be aligned with the evolving context.[27] This alignment can be done through the continual renewal of assessment methods and their tools based on best practices and context.[26]

The classroom teaching activities were aligned with the described curriculum and enacted as described by the curriculum. The study revealed challenges associated with the authenticity of the content being taught and the examples used to support learning.[28,29] Authenticity allows students to learn from real-life examples and allows such examples to influence their understanding of concepts.[30] The nature of the curriculum model was not flexible enough to accommodate the contextual realities for the students, thereby reducing the meaning of learning in this module. NEIs are recommended to transform their curriculum models to embrace competency- and problem-based contextual curricula that allow for flexibility and alignment with contextual realities.[31]

Students in the clinical environment struggle to apply theoretical approaches to nursing administration owing to several factors. The pervasive shortage of qualified nurse educators and clinical nurses in Africa affects their availability for students during clinical practice[8] Revolutionary approaches, such as a robust preceptorship,[32,33] need to be adopted by all NEIs to enhance students' supervision and mentoring during nursing administration placements. Various preceptorship models have been developed for nurses in Africa[32,34,35] and the operationalisation of such models needs to be underpinned by relevant contexts driven by excellence in nursing practice. The preceptors supporting the students should be qualified professionals who must undergo training[32,36] on how to support students and be engaged with best practices in nursing administration.

Conclusions

The International Council of Nurses[2] has put great emphasis on the need for training of nursing administration competencies in pre-registration programmes. In Africa, nurses comprise the bulk of the healthcare delivery system[8] and are often expected to manage health centres and primary healthcare clinics. Yet, nursing students, the future of such a system, are struggling to meet expected learning outcomes related to nursing administration owing to the non-alignment of learning outcomes, content and assessment of the related module. NEIs are therefore expected to fortify their efforts through sound evidence-based programmes in the training of nurses to be able to function independently in administration roles.

To achieve this, NEIs in low-resource settings must radically transform their pre-registration nursing curricula to incorporate contemporary issues and clinical contextual realities to enhance the utility of nursing administration learning outcomes. The NEIs in Africa should also adopt problem-based contextually relevant curricula to enable the inclusion of locally relevant examples that mirror the respective clinical environments. Adoption of preceptorship models by NEIs to capacitate nursing staff in mentoring and supporting students during clinical learning and engagement of organic assessment methods applied in authentic environments is paramount to enhance the credibility of assessment outcomes.

This study was conducted in one NEI in a low-resource country, but Bvumbwe and Mtshali[8] explain that most of the NEIs in sub-Saharan Africa face similar challenges and seem to be using similar curriculum models. Further research in this area should consider challenging the relevance of nursing administration learning outcomes within the remit of universal health coverage.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to the key informants for the valuable insights provided. We thank Mr F Muzeya for helping to conduct the focus group discussions. Many thanks to Dr A G Mubuuke, Dr N Mannathoko and Prof. M Rowe for their helpful comments on this paper. Lastly, we say thank you to the Sub-Saharan Africa-FAIMER Regional Institute (SAFRI) family for their support and encouragement during this journey.

Author contributions. BM and LNB designed the study. BM collected data and undertook the preliminary analysis and interpretation, which were subsequently reviewed by LNB and CNN. CNN greatly contributed to refining the conceptualisation, critical revision of important scientific content and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final article.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Brown RA, Crookes PA. What level of competency do experienced nurses expect from a newly graduated registered nurse? Results of an Australian modified Delphi study. BMC Nurs 2016;15(45):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0166-2 [ Links ]

2. International Council of Nurses (ICN). Nursing care continuum framework and competencies. 2008. https://siga-fsia.ch/files/user_upload/08_ICN_Framework_for_the_nurse_specialist.pdf (accessed 28 February 2020). [ Links ]

3. Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Nordstrom G. The first year as a graduate nurse: An experience of growth and development. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(14):1877-1885. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02229.x [ Links ]

4. Peres A, Ezeagu T, Sade P, Souza P, Gómez-Torres D. Mapping competencies: Identifying gaps in managerial nursing training. Texto Context - Enferm 2017;26(2):e06250015. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072017006250015 [ Links ]

5. Sade PM, Peres AM. Development of nursing management competencies: Guidelines for continous education service. J School Nurs 2015;49(6):988-994. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420150000600016 [ Links ]

6. Fink R, Krugman M, Csey K, Goode C. The graduate nurse experience: Qualitative residency program outcomes. J Nurs Admin 2008;38(7):341-348. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nna.0000323943.82016.48 [ Links ]

7. Theisen JL, Sandau KE. Competency of new graduate nurses: A review of their weaknesses and strategies for success. J Contin Educ Nurs 2013;44(9):406-414. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20130617-38 [ Links ]

8. Bvumbwe T, Mtshali N. Nursing education challenges and solutions in sub-Saharan Africa: An integrative review. BMC Nurs 2018;17(7):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-018-0272-4 [ Links ]

9. Blaauw D, Ditlopo P, Rispel LC. Nursing education reform in South Africa - lessons from a policy analysis study. Glob Health Action 2014;7:1-12. https://doi.org/10.3402%2Fgha.v7.26401 [ Links ]

10. World Health Organization. State of the world's nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/nursing-report-2020 (accessed 10 April 2020). [ Links ]

11. Botma Y. How a monster became a princess: Curriculum development. S Afr J High Educ 2014;28(6):1876-1893. https://doi.org/10.20853/28-6-431 [ Links ]

12. Fullerton JT, Thompson JB, Johnson P. Competency-based education: The essential basis of pre-service education for the professional midwifery workforce. Midwifery 2013;29(10):1129-1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.07.006 [ Links ]

13. Ramasubramaniam S, Angeline G. Curriculum development in nursing education. Where is the pathway? IOSR J Nurs Health Sci 2015;4(5):76-81. https://doi.org/10.9790/1959-04537681 [ Links ]

14. Allan HT, Smith P, O'Driscoll M. Experiences of supernumerary status and the hidden curriculum in nursing: A new twist in the theory-practice gap? J Clin Nurs 2011;20(1):5-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03570.x [ Links ]

15. Jamshidi N, Molazem Z, Sharif F, Torabizadeh C, Kalyani M. The challenges of nursing students in the clinical learning environment: A qualitative study. Sci World J 2016;1(6):13-21. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1846178 [ Links ]

16. Makhakhe AM, Khalanyane T. Nurses' experience of the transition from student to professional practitioner in a public hospital in Lesotho. Int J Nurs Sci Res 2013;1(1):1-22. [ Links ]

17. Harden RM, Dent J, Hodges B, eds. Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2013:8-11. [ Links ]

18. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2013:18. [ Links ]

19. Brown KM, Elliott SJ, Leatherdale ST, Robertson-Wilson J. Searching for rigour in the reporting of mixed methods population health research: A methodological review. Health Educ Res 2015;30(6):811-839. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyv046 [ Links ]

20. Giddings LS, Grant BM. From rigour to trustworthiness: Validating mixed methods. In: Andrew S, Halcomb EJ, eds. Mixed Methods Research for Nursing and the Health Sciences. Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009:126-127. [ Links ]

21. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J 2009;9(2):27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027 [ Links ]

22. Sims JM. A brief review of the Belmont report. Crit Care Nurs 2010;29(4):173-174. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcc.0b013e3181de9ec5 [ Links ]

23. Biggs J. Aligning teaching for constructing learning. 2013. http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/resources/database/id477_aligning_teaching_for_constructing_learning.pdf (accessed 21 February 2020). [ Links ]

24. Joseph S, Juwah C. Using constructive alignment theory to develop nursing skills curricula. Nurse Educ Pract 2012;12(1):52-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.05.007 [ Links ]

25. Khan BA, Hirani SS, Salim N. Curriculum alignment: The soul of nursing education. Int J Nurs Educ 2015;7(2):83-86. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-9357.2015.00080.X [ Links ]

26. Kulasegaram K, Rangachari PK. Beyond 'formative': Assessments to enrich student learning. Adv Physiol Educ 2018;42(1):5-14. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00122.2017 [ Links ]

27. Sood R, Singh T. Assessment in medical education: Evolving perspectives and contemporary trends. Natl Med J India 2012;25(6):357-364. [ Links ]

28. Poindexter K, Hagler D, Lindell D. Designing authentic assessment strategies for nurse educators. Nurse Educ 2015;40(1):36-40. https://doi.org/10.1097/nne.0000000000000091 [ Links ]

29. Wu XV, Heng MA, Wang W. Nursing students' experiences with the use of authentic assessment rubric and case approach in the clinical laboratories. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35(4):549-555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.009 [ Links ]

30. Iucu RB, Marina E. Authentic learning in adult education. Soc Behav Sci 2014;(14):410-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.702 [ Links ]

31. World Health Organization. Transforming and Scaling up Health Professionals' Education and Training. Guidelines. Geneva: WHO, 2013. [ Links ]

32. Jeggels JD, Traut A, Africa F. A report on the development and implementation of a preceptorship training programme for registered nurses. Curationis 2013;36(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v36i1.106 [ Links ]

33. Lethale SM, Makhado L, Koen MP. Factors influencing preceptorship in clinical learning for an undergraduate nursing programme in the North West Province of South Africa. Int J Afr Nurs Sci 2019;10:19-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2018.11.006 [ Links ]

34. Asirifi M, Ogilvie L, Barton S, et al. Reconceptualising preceptorship in clinical nursing education in Ghana. Int J Africa Nurs Sci 2019;10(4):159-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2019.04.004 [ Links ]

35. Happell B. A model of preceptorship in nursing: Reflecting the complex functions of the role. Nurs Educ Perspect 2009;30(6):372-376. [ Links ]

36. Dennis-Antwi J. Preceptorship for midwifery practice in Africa: Challenges and opportunities. Evidence-based Midwifery 2011;9(4):137-142. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

B Masava

belovedmas@gmail.com

Accepted 21 July 2020