Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 n.2 Pretoria Jun. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2020.v12i2.1243

RESEARCH

Readiness of allied health students towards interprofessional education at a university in Ghana

J QuarteyI; J DankwahII; S KwakyeIII; K AcheampongIV

IPhD; Department of Physiotherapy, School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

IIBSc; Department of Physiotherapy, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana

IIIBSc; West Africa Football Academy, Sogakope, Ghana

IVBSc; Department of Physiotherapy, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Interprofessional education (IPE) is an important academic approach for preparing healthcare students to provide patient care in a collaborative team environment, which improves patient care outcomes and increases patient satisfaction. IPE has been shown to eliminate segmented education between healthcare professionals, and thus renounces hierarchies, misperceptions and miscommunications

OBJECTIVES: To determine the readiness of allied health students towards IPE

METHODS: This was a cross-sectional study that involved 299 second- to fourth-year allied health students recruited from various departments at the University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale was used to obtain data regarding readiness of allied health students towards IPE. Data obtained were analysed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., USA). Differences between groups based on the levels and programmes of study, respectively, were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA

RESULTS: The majority of participants (n=155; 67.7%) had previous experience in the health environment. The overall response of allied health students' readiness towards IPE was high. This readiness did not differ between the different levels of study (p=0.985) and the various programmes of study (p=0.726

CONCLUSION: The study revealed that allied health students value teamwork and collaboration and appear ready for participation in IPE activities. Formatively planning IPE activities may be helpful in developing multidisciplinary teamwork

The complex nature of current healthcare, which aims to cure and prevent disease and also to promote health, requires effective collaboration between various healthcare professionals.[1] However, interprofessional collaboration is not self-evident and is fraught with problems, such as ineffective communication, poor interprofessional relationships, lack of trust between team members and an underestimation of other health professionals' roles.[2] These factors impede the effective involvement of all team members in collaborative decision-making regarding patient care and the implementation of healthcare services.[1] To partially address this problem, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the introduction of interprofessional education (IPE), which helps future healthcare professionals to prepare for their collaborative role in the healthcare system.[3]

IPE offers students from different health professions the opportunity to learn with, from and about each other's profession and has been recognised as a means to safely promote and develop collaborative skills that students would require in their profession.[1] Research revealed that health professionals who were trained to collaborate as a team in an IPE setting during their student years, were far more likely to be effective collaborators in their future professional clinical setting.[4] IPE has been shown to eliminate segmented education between healthcare professionals, and therefore overlooks hierarchies, misperceptions and miscommunications.[5]

Furthermore, 'the aging society, the increase in chronic illnesses and patients in need of complex care, and rapidly evolving scientific knowledge have necessitated interprofessional collaborations for optimal patient care'.[6] However, a 2010 Lancet report states that current healthcare students are not being adequately prepared for interprofessional collaboration owing to the profession-specific nature characterising most health professions education and socialisation.[7]

Keshtkaran et al.[8] reported that healthcare students had positive attitudes towards teamwork and collaboration. Fallatah et al.[9] revealed that medical students and graduates valued IPE and thought that its implementation in their education would improve patient care and healthcare-provider satisfaction. Furthermore, others[5,10] reported that most healthcare students have positive attitudes towards IPE at the undergraduate levels of their professional programme.

Casual conversations with physiotherapy students in their clinical year regarding clinical rotations and attachments in two hospitals in Ghana, revealed that most healthcare professionals do not possess sufficient knowledge of the role of members of other health professions in the treatment or management of patients. Although similar studies were carried out in other countries and among other health professionals, there seems to be a dearth of information with regard to this topic for allied health professions at a university in Ghana. Findings from this study generated baseline information about IPE for the allied health professions' training programmes, such as effective collaboration with other healthcare professionals to improve patient care or management and recovery. Ultimately, it could serve as a basis for reviewing the curricula to promote IPE. Hence, there was a need to conduct this study among allied health students in the specific university in Ghana.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study performed at the School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana. The study involved second- to fourth-year allied health students from physiotherapy, dental laboratory science, dietetics, occupational therapy, diagnostic radiography/radiotherapy and medical laboratory science. The Yamane[12] formula, n=N/(1+Ne2), was used to determine the sample size, while the convenient sampling method was used to recruit respondents for the study; n with an error margin, e = allowable error of 5%, and N=population (students, n=534). Therefore, n=534/(1+534(0.05)2)=534/(2.335)=228.7. This was rounded off to 229.

The Parsell and Bligh[13] modified version of the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) (Appendix 1 (http://www.ajhpe.org.za/public/files/1243.doc)) was used to measure the readiness towards IPE.[11] The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were confirmed with an alpha coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) of 0.81 and hence an internal consistency of 0.90.[13] A data-capturing form was used to obtain the demographic details of the respondents.

The RIPLS is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, as follows: strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, and strongly disagree = 1. Domain 1 focuses on the aspects of teamwork and collaboration (items 1 - 9); domain 2 focuses on negative professional identity towards other professions (items 10 - 12); domain 3 focuses on positive professional identity (items 13 - 16); and domain 4 focuses on the roles and responsibilities of professionals (items 17 - 19).[13]

The research was explained to respondents; those who agreed to participate signed a consent form. Copies of the questionnaire and data-capturing form were administered to students in their lecture halls. The questionnaire, which takes 10 - 15 minutes to complete, was retrieved from the respondents on the same day. Data were collected within 4 weeks (middle of February - middle of March 2019) during semester 2 of the 2017/2018 academic year. The data obtained were entered into a database and analysed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., USA). The demographic data of the respondents were analysed and described in terms of frequencies and percentages. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine significant associations between groups based on level or year of study, and groups based on different healthcare disciplines, with regard to the readiness of allied health students towards IPE at the University of Ghana. A p-value of <0.05 was interpreted as significant.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Protocol Review Committee of the School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, University of Ghana (ref. no. SBAHS-PH./10513879/SA/2017-2018).

Results

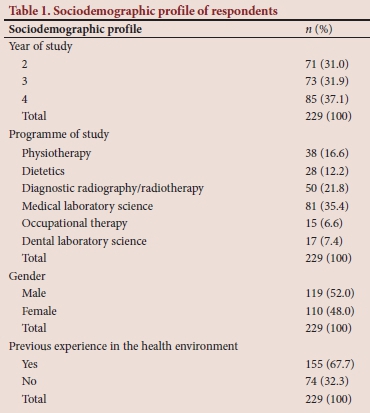

A total of 229 respondents from 6 allied health professions took part in the study. Students were almost equally spread across the three year levels; 119 (52%) were males, 71 (31%) were second-year students and the majority (n=155; 67.7%) had previous experience in the health environment (Table 1). Thirty-eight (16.6%) of the respondents were physiotherapy students, and 81 (35.4%) were medical laboratory science students (Table 1).

Table 2 provides information about responses to statements regarding teamwork and collaboration, negative and positive professional identity and roles and responsibilities in IPE. The item 'Patients would ultimately benefit if healthcare students work together' under the domain 'Teamwork and collaboration', obtained the highest response (n=165; 72.1%). Students were also generally affirmative regarding positive professional identity (Table 2). The item 'Shared learning before and after qualification will help me become a better team worker', under the domain 'Positive professional identity', also obtained the highest response (54.1%). Under the domains 'Roles and responsibilities' and 'Negative professional identity towards other professions', students understood their roles and found that learning with other undergraduate healthcare students was necessary.

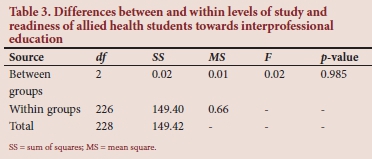

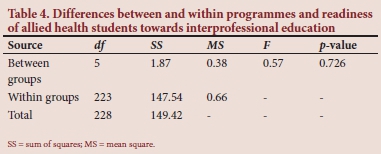

The difference between the level of study and readiness of allied health students towards IPE at a university in Ghana was not statistically significant (Table 3). The difference between and among the various programmes of study and readiness of allied health students towards IPE was also not statistically significant (Table 4).

Discussion

This study revealed that the overall response of allied health students' readiness towards IPE is high. This result corroborates the findings of Lairamore et al.,[10] who showed that most healthcare students have a positive readiness towards IPE at the undergraduate levels of their professional programme. This may be due to problems that students encountered during their clinical rotations and placements. Addressing problems of teamwork and collaboration, professional identity and roles and responsibilities would be more beneficial to students.

The study also revealed details of the teamwork and collaboration domain, i.e. that most students agreed with the significance of teamwork and collaboration with other healthcare professionals. The highest-rated item under the domain was 'Patients would ultimately benefit if healthcare students work together'. This reveals that allied health students are willing to work in an effective collaborative manner to improve patient outcomes, which is similar to the findings of Keshtkaran et al.,[8] who reported that students showed readiness towards teamwork and collaboration.

Students generally value sharing of experiences with other healthcare disciplines, as observed in the second domain (positive professional identity). The highest-rated item under the domain was 'Shared learning before and after qualification will help me become a better team worker'. Students believe that IPE will facilitate their team-working skills and, thus, improve health outcomes. The third domain, 'Negative professional identity towards other professions', which received low responses, indicates that students value collaborative learning with other health professions students. This highlights students' need for shared learning, which would improve communication skills among health professions students and prevent conflicts. The fourth domain, 'Roles and responsibilities', shows that students understood their roles as healthcare professionals. This may be due to the well-structured tuition in the various disciplines. However, students had divergent responses to the item 'I have to acquire much more knowledge and skill than other students in my own faculty', possibly because of individual differences they might have towards acquiring knowledge and skills.

The results showed that there was no difference between level of study and readiness or between the various allied health students towards IPE at the University of Ghana. Therefore, although students are at different levels of study, they have an equal understanding of the benefits of IPE if it is available to them. This is at variance with the findings of Olenick et al.,[5] who reported a significant difference in the perception of IPE between the higher levels of education (medical residents and interns), who had a higher perception of IPE, and the lower levels (medical and nursing students). The difference shown in that study might be the result of residents and interns having obtained some level of experience of healthcare services and having learnt about interprofessional work, unlike medical and nursing students.

The results showed that there was no difference between programme of study and readiness and also not for the various allied health students towards IPE at the University of Ghana. Although students were in different allied health disciplines, they seem to have understood what it meant to work together as healthcare professionals to improve patient care or management and delivery. This might be due to their experiences during clinical placements and rotations. This is also at variance with the outcomes of Keshtkaran et al.,[8] who reported significant differences among disciplines. The difference found in that study might be due to medical students feeling superior to the nurses and, therefore, not experiencing the need to work with them.

Conclusions

Allied health students seem to be ready for participation in IPE activities. Formatively planning IPE activities might assist in developing multidisciplinary teamwork, which has implications for restructuring the allied health professions curriculum to promote IPE, which could be helpful for the clinical learning of allied health students.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. Special thanks go to the 2017/2018 allied health professions students of the School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences for their participation, and to the management of the School for their support.

Author contributions. JQ and JD contributed to the study design, and collected and analysed the data. SK and KA assisted with data collection, and sourced and reviewed the relevant literature. JQ, JD, SK and KA wrote and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, revised the draft version and approved the final version for submission.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Lestari E, Stalmeijer RE, Widyandana D, Scherpbier A. Understanding students' readiness for interprofessional learning in an Asian context: A mixed-methods study. BMC Med Educ 2016;16(1):179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0704-3 [ Links ]

2. Besner J. Is interprofessional practice rhetoric or reality? Canad Nurse 2008;104(3):48-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470690352.ch3 [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education Collaborative Practice. Geneva: WHO, 2010. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561821003676325 [ Links ]

4. Jacobsen F, Lindqvist S. A two-week stay in an interprofessional training unit changes students' attitudes to health professionals. J Interprofes Care 2009;23(3):242-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820902739858 [ Links ]

5. Olenick M, Allen LR, Smego RA Jr. Interprofessional education: A concept analysis. Adv Med Educ Pract 2010;1:75. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S13207 [ Links ]

6. Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional education: A review of context, learning and the research agenda. Med Educ 2012;46(1):58-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04143.x [ Links ]

7. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376(9756):1923-1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61854-5 [ Links ]

8. Keshtkaran Z, Sharif F, Rambod M. Students' readiness for and perception of inter-professional learning: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 2014;34(6):991-998.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.008 [ Links ]

9. Fallatah HI, Jabbad R, Fallatah HK. Interprofessional education as a need: The perception of medical, nursing students and graduates of Medical College at King Abdulaziz University. Creative Educ 2015;6(2):248. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2015.62023 [ Links ]

10. Lairamore C, George-Paschal L, McCullough K, Grantham M, Head DA. Case-based interprofessional education forum increases health students' perceptions of collaboration. Med Sci Educ 2013;23(3):472-481. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03341670 [ Links ]

11. Coster S, Norman I, Murrells T, et al. Interprofessional attitudes amongst undergraduate students in the health professions: A longitudinal questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Studies 2008;45(11):1667-1681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.008 [ Links ]

12. Yamane T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1967. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446402400434 [ Links ]

13. Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Med Educ 1999;33(2):95-100.https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J Quartey

neeayree@googlemail.com

Accepted 10 December 2019