Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 n.2 Pretoria Jun. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2020.v12i2.1214

RESEARCH

The benefits of experiential learning during a service-learning engagement in child psychiatric nursing education

A C Jacobs

MSocSc (Nursing); School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Children, families and communities are affected by mental health challenges caused by high levels of violence and domestic upheaval in South African (SA) communities. There are too few specialised healthcare professionals, e.g. nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists and social workers, to meet the enormous mental healthcare needs of children and adolescents in the country. Because of the unique challenges people face in this context, professionals need to be trained in all aspects of child psychiatric nursing. One important way to provide this training could be a service-learning strategy. In this approach, nursing students are taught how to engage and educate communities by means of community-outreach programmes that form part of the curriculum. The purpose of this article is to report on nursing students' experiences during their community-engagement outreach programmes in the challenging SA healthcare context

OBJECTIVES: To explore and describe students' community-based learning experiences during outreach programmes

METHOD: A qualitative methodological approach used structured reflection reports of 47 students over 3 years as data. Participants' responses were thematically analysed by content

RESULTS: Nursing students experienced community-learning engagement as thought provoking. They were able to practise their professional development within a collaborative environment, which built self-confidence and stimulated critical thinking. They indicated that the experience made them aware of the needs of the community and enabled them to share reciprocal knowledge. It helped them to integrate theory with practice, develop responsible citizenship and enhance professional development

CONCLUSION: Evidence from a challenging context supports the use of service learning as an ideal approach to develop students' professionalism, ethical responsibility and personal growth to become responsible citizens who can engage with mental health users in the community

Challenging contexts place a greater onus on child psychiatric nurses who work in communities. In South Africa (SA), many children suffer from mental health disorders due to high levels of violence and family problems in their communities.[1,2] A rise in violent conflicts at schools coincides with the themes of emotional and behavioural dysfunction of children, and the need for mental health resources at schools and in communities.[1] There is a dearth of specialised healthcare professionals, such as nurses, occupational therapists and social workers, to meet the enormous mental healthcare needs of children and adolescents.[1,2]

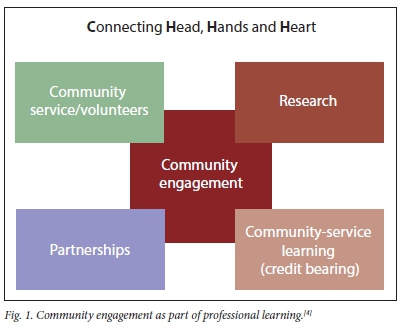

Challenges in this context require thoughtful curriculum development. One such response is illustrated by the postgraduate diploma in child psychiatric nursing that was developed by a university in response to the mental health needs of children in SA.[3] A family-centred focus in the programme underscores both theory and practice.[3] Therefore, a service-learning and community-engagement approach is integrated in the child psychiatric nursing curriculum by means of frequent outreach programmes to the community. Community engagement is an integral and core part of higher education and health education in SA, and it rests upon four pillars (Fig. 1).

Community service is a core function of the study university and educators pursue it by ensuring that they build sustainable partnerships to co-ordinate collaborative partnerships with different stakeholders.[4] Annually, child psychiatric nursing students join the specialised child unit for community engagement programmes at the Free State Psychiatric Complex, Bloemfontein, which is an outreach to rural communities. Students work collaboratively in a multidisciplinary team in different rural towns to attain experiential learning. Partnerships benefit all involved stakeholders.[5] The goal of the programme is to expose students and to empower them to respond to the realities of the social and human dynamics in their communities.[4]

Students were exposed to a community only after the basics of theoretical and practical components were covered during student-centred learning activities. First, the training school employs standardised patient simulation as a student-centred learning strategy to bridge the theory-practice gap.[6] Students are expected to have a presence in the community throughout the year and to reflect on their experiences regularly in reflective assignments. This premise links to a discipline-based model for community-engagement teaching.[7,8] Nursing educators need to recognise the importance of a supportive academic and clinical environment for specialised healthcare professionals, to encourage engagement and active participation and to prepare students to solve real-life problems.[9]

The community service-learning strategy improves students' skills, while students support and guide children, parents and families of children with mental health problems. The strategy also helps students to engage in their own professional and personal development. The goals of the service-learning placement is to stimulate thought, guide, clarify and encourage scholarship, inspire dialogue and model and facilitate collaborative discussion with members of multidisciplinary and multiperspective-thinking teams.[5,9] Constructivist teachers motivate students to assess how an activity assists them in gaining understanding. Knowledge leads to further cognitive development and meaning as a result of experiences.[10]

Regular guided critical reflection is a rigorous and necessary component of any experiential learning activity and an effective tool for use in assessment. It assists and deepens students' understanding of key theoretical and practical applications and their professional roles in the community. Reflective writing is particularly beneficial and fundamental to improving critical thinking skills of students.[9,11] The educator facilitates this learning by including reflective writing assignments in the curriculum to help students strengthen their critical thinking and reflective skills. Students must move beyond the surface of learning or observing, and engage with the content on a higher level.[12] Student reflections are guided by theoretical literature for understanding, analysis of actions taken and evaluation of the results of issues at hand.[11,12] De Swardt et al.[11] specify that guided reflection raises the awareness of students of the level of their own competencies.

It is the responsibility of educators to investigate their practice to ensure that service-learning projects are aligned to educational objectives, that they provide quality training and apply new ideas in their programmes.[9] A deeper exploration of students' perspectives enables the educator to remain relevant in the application of service learning to child psychiatric nursing education and, in the process, to make applicable recommendations to other academic programmes that could benefit from the results achieved. This research is the result of the documented reflection reports of students of their involvement in and learning during the 1-year child psychiatric nursing programme. This article, therefore, deals with an investigation into students' perceptions of their community-based learning during outreach programmes.

Methods

A qualitative, explorative and descriptive research design was used to explore and describe the perceptions of students enrolled on the child psychiatric nursing programme regarding their learning during community-engagement placement.[13] The research technique comprised an instrument for guided reflection. A structured reflection report was given to students to hand in after every exposure to community-based experiential learning.

Population and sampling

The study population comprised all 47 students registered for the post-basic Child Psychiatric

Nursing programme from 2015 to 2017. A purposive sampling technique was used and all 47 nursing students' reflection reports regarding the outreach experience were used.[14]

Data collection and analysis

Data were gathered directly after each outreach experience by means of reflection reports from each child psychiatric nursing student, whose responses were thematically analysed by content.[13]

Ethical principles

The ethical requirements prescribed by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein (ref. no. HSREC137/2016) were adhered to, as were the ethical principles of beneficence, respect for human dignity and justice.[14]

Results and discussion

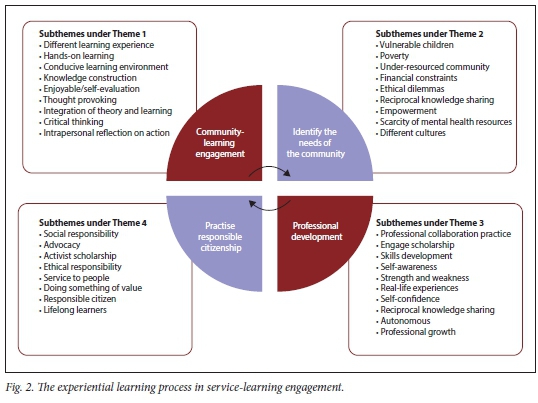

Four main themes emerged during data analysis, which revealed that the students essentially work through a process. First, they engage in community learning through the integration of theory into practice. Students identify the needs of the community, but also engage as scholars by improving their professional development and advancing into responsible citizens. These four major themes were extrapolated with several subthemes (Fig. 2). The major themes are important elements of the experiential service-learning process of the students. A discussion of this study's most important findings by theme follows.

Theme 1: Community-learning engagement

The students experienced the community-learning engagement as a different, enjoyable learning experience, and as a learning environment conducive to integrating theory and practice. Through their intrapersonal reflection on action they indicated it as a 'Positive way of learning' (P26) and that they 'enjoyed the time I have spent' (P18). In the process, they were stimulated to think critically and they described service learning as thought provoking. Service learning helps students to foster higher levels of thinking, builds problem-solving skills and enhances the application of learning to real-world settings.[15] Janse van Rensburg[16] and Adegbola[9] recommended service-learning engagement for students to integrate theory and practice (knowledge, skills and attitudes) in various fields.

The students described outreach community-learning engagement as follows:

'Whoever came up with the outreach idea has really done justice to the children by taking the services to them, though the interval between outreaches are longer, but at least the people know that there is help.' (P8) 'Outreach has practical opportunities to prepare students for the public as they are exposed to different situations.' (P35)

Furthermore, intrapersonal reflection on action provided by students assisted the nurse educator to assess the preparation of nurses for their roles in the clinical setting. A student reported that:

' It was a good learning environment and free from any intimidation.

I was able to measure the little knowledge I have about first interview assessment, diagnosis and intervention.' (P30)

Structuring the curriculum to provide learning experiences that prepare students to meet the healthcare needs of communities is the work of academic faculties.[15] The following responses could help educators:

'Beginning, I was still clueless.' (P11)

'I realised that one does not read as much.' (P11)

'I enjoyed outreach more as I got exposed to different environments with different kinds of children who presented with different problems.' (P16)

Students acknowledged that community engagement was an important assignment for students to learn. Students valued hands-on learning:

' It gives an opportunity to link theory to practice and apply learning in community context.' (P34)

Outreach to a community-learning environment exposed students to different learning experiences that relate to all the facets of their training.

Theme 2: Needs of the community

Students experienced that valuable mental health services are rendered in the community: 'Outreach was about empowering patients, parents, and professionals with necessary skills to manage mental ill-health and parenting through workshops' (P2) that could empower the people to take responsibility for their own mental healthcare. Through their encounters, students developed a better understanding of and empathy for the needs of children and the community. Face-to-face learning experiences enhanced the nursing students' sense of connection with the community, which fostered a sense of belonging.[17,18] Students were confronted with reality in the community, as explained by one student in a reflection:

'I have always thought that people that used the phrase "you cannot save them all" or "you cannot save the world" were excusing themselves for doing more than what they currently are doing. But, I learned that one could do as much as resources will allow, and I had to learn to appreciate and be thankful for the little that I had done for those families in the short time I had with them.' (P2)

Students developed an appreciation of the nature of the community by being involved in the outreach programme.[15] One student said:

'I have learned a lot from the outreach and most importantly I was touched by the challenges the children are facing in that community, especially alcohol abuse of the parents. I have learned that when you engage families in the care of their child, they feel like partners and we get a positive result.' (P26)

The students experienced different cultural values[19] and learnt to respect the wishes of community members and how the students could make a difference:

'At home the child was labelled as a naughty, stubborn child - family seemed not accepting her condition. I did manage to give them parental guidance.' (P38)

'The community was different. In one family two or three are mentally ill or the child is abused or raped. I asked myself what 'is1 wrong with this community.' (P39)

They recognise that not all situations could be treated in the same way: 'Particular intervention or initiative might not apply for every community' (P2)

The students identified community needs and experienced ethical dilemmas:

' I was quite challenged by the economic situation which was disrupting my function as a mental health professional - and could see the consequences thereof: some would not even come back due to lack of financing transport back and forth to the hospital.' (P2)

It was not always easy for the students, as they experienced some challenges:

' Far distance - we were leaving early in the morning. We had good welcoming smiles.' (P28)

However, they experienced it as worthwhile to endure:

' This made me feel proud of myself as I felt I was doing something of value for patients.' (P7)

The students learnt to act on the challenges and needs of the community, which stimulated them to do more for a better outcome for the user of the mental health service.

Theme 3: Professional development

Working in a team with other healthcare providers helped students to deliver better care to the people. One shared that it was a 'Good learning place for students and the team members are always ready to guide the students'. (P4) Students need to participate as members of an interdisciplinary team and to collaborate with members of a selected community to identify mental health-related issues and concerns.[15]

The experiences of others during community engagement - specifically hearing from their peers how the children responded - and the types of questions their peers asked, helped students to develop professionally. Overall, learning effectiveness is improved when individuals are highly skilled in engaging, collecting, interpreting and utilising data from multiple sources to assist in improving the health of a community.[15,18] The reciprocity of knowledge sharing was recognised, as the students shared the benefits of their participation in service learning with their team members and became engaged scholars, which contributed to their professional development. Moreover, reflection reports helped them to do intra- and interpersonal reflection actively. Self-awareness helped the students to grow professionally and personally.[20] The students demonstrated respect and self-awareness while participating as members of a multidisciplinary team, and could contribute a nursing perspective. Furthermore, the 'Opportunity to work independently' (P11) helped students to become more confident:

'I found the transition initially different and confronting, but by reviewing my knowledge and skills I was able to recognise that I already passed a great deal of knowledge and skills that were required for the different units, which bolstered my confidence and allowed me to focus on some issues that I had not had the opportunity to develop prior to this practical experience, thereby further developing myself as a registered nurse working in a mental unit.' (P2)

Other students reported:

' I felt overwhelmed of having completed an assessment with the help of the other professional nurses.' (P19)

'Useful method for the student to learn and it promotes self-awareness, self-evaluation and self-confidence.' (P32)

The experience made students aware of their strengths and weaknesses:

'I could not manage the group I started.' (P14)

'Focus on these areas to develop them and turn them into strengths.' (P21)

Several students valued the opportunity to learn and practise in a reciprocal knowledge-sharing environment, to identify gaps in their knowledge and skills. One student reported:

' I feel we learn more when we are at the outreach than at the clinic, because there we have more one on one consultation with our mentor and we are able to identify our weaknesses and find ways to work around them and find our strong points and enhance on them.' (P47)

It seems that the community engagement helped students to become autonomous. One shared that:

'Outreach gave more experience on almost every aspect of my training and now I feel like I can make it out there as a child psychiatric nurse.' (P17)

Community engagement also prepared the students, as one mentioned:

'I have learned a lot of things that I did not know about my job that these outreach programmes opened my eyes.' (P6)

Osman and Peterson[21] believe that students, through their experience, construct their own understanding of the world around them, and then they will learn. Service learning provides a rich context for students to learn through real-life experiences, and to develop academically, socially and as civic participants in a democracy. Critical thinking is stimulated in various ways during this community-engagement experience.

Theme 4: Practising responsible citizenship

Even though students developed professionally, they were required to make responsible decisions beyond their scope of practice and, thus, the experience touched on their social responsibilities as citizens of SA. In the communities, students were confronted with challenging issues, such as ethical dilemmas, inadequate human resources and financial and logistical problems. One student wrote:

'I felt that their right to confidentiality was being violated.' (P2)

Another student expressed that they needed to empower the community:

' Professional nurses - it is also their role to empower others with their knowledge and skills.' (P33)

These realisations helped the students to develop their activist scholarship, and to deliver service to the people.[22]

Most students reported finding the hands-on education that service learning provides valuable:

'I can say that I can be able to go back to my institution with the knowledge that I have gained at these outreach programmes and incorporate it to bring about change.' (P8)

One student summarised the experience:

'Community outreach services should bring specialised healthcare services next to the home of the clients. It is to make healthcare services equally accessible to all SA citizens irrespective of colour, economic status and whether it is in rural areas or townships.' (P23)

From these responses it is evident that nursing students are serious about their development as advanced child psychiatric nurses, and that they will advocate for their patients' rights and become involved citizens.

Discussion

The results indicate that students experienced how important community-service learning is. Students could link theory to practice, apply learning in a specific community context and address specific needs of the community in a holistic manner. Nurse educators can increase the students' effectiveness by including service-learning concepts and actual field experience in academic education. Through experiential learning education, students discovered relationships among ideas, rather than passively receiving information.[23] Reciprocal learning takes place for students and community members. The students engaged in critical thought and discussion about the construction of knowledge.[15,21] Mayne and Glascoff[15] claim, 'It is an effective way for educators to prepare nurses for their roles in healthcare for the 21th century'. Nursing students learnt about all the important components of child mental health, and they could identify what Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory[24] means by the explanation that a child is exposed to and influenced by many systems. Because children are part of families, communities and society, they cannot be treated in isolation. The students worked in the midst of all these systems. They experienced the needs of the community and, more specifically, the family.

During their outreach sessions, nursing students could compare their performance and learn from one another, as well as from professional team members, e.g. social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists and occupational therapists. A good working relationship among members of the multidisciplinary team and provision of support on personal and professional levels are important for improving the professional development of students.[18] Nurse educators should continue exploring reciprocity learning opportunities such as these, where students can develop self-awareness and critical thinking, which promote the development of professional competence, and where they learn to value and respect the authenticity of others.

Based on the students' comments, they learnt the value of intercultural communication, advanced therapeutic relationships cross-culturally, improved their language skills and collaborated with community liaisons.[19] Focused intercultural and collaborative partnerships have the potential to prepare students to become more comfortable with caring for healthcare users who differ from them, and to encourage students to be leaders in meeting the healthcare needs of a global and multicultural society.

Conclusions

Learning is best conceived as a process, not in terms of outcomes. This experiential learning process in service-learning engagement (Fig. 2) will improve learning in higher education, because it draws out students' beliefs and ideas about the subject, so that they can examine, test and integrate new, more refined ideas. They can move back and forth between feeling and thinking. This type of learning involves the integrated functioning of the whole person, who thinks, feels, perceives and behaves. In this study, learning happened from synergetic transactions between the student and the community and, in the process, social knowledge was created and recreated in the personal knowledge of the student.

This experiential learning process could slot into any curriculum, and can expose and empower students in relation to the realities of the social and human dynamics in communities. Evidence supports the use of community learning to develop students' professionalism, ethical responsibility and personal growth - in that way they become responsible citizens. They realise how important it is to become community-service volunteers in their careers and being SA citizens. In the process, they practise responsible citizenship. Service learning provides rich opportunities for child psychiatric nursing students and is very relevant to nursing education.

The mental health of children and families in communities is very important for the future of any country; therefore, healthcare professionals must be trained to address any mental challenges that may occur. Training institutions need to support the inclusion of service learning in the curriculum to train student nurses to be competent professionals, who are socially accountable. Future studies should include the perceptions of community partners and mental health users in the community about this type of learning and service.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. I wish to thank the child psychiatric nursing students; Sr Ester Mabizela, instigator of outreach programmes, Free State Psychiatric Complex Child Unit personnel; Free State communities; School of Nursing and the University of the Free State for their personal, professional and logistical support.

Author contributions. Sole author.

Funding. Financial support from the University of the Free State.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Jacob N, Coetzee D. Mental illness in the Western Cape province, South Africa: A review of the burden of disease and healthcare interventions. S Afr Med J 2018;108(3):176-180. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12904 [ Links ]

2. Sankoh O, Sevalie S, Weston M. Mental health in Africa. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6(9):E954-E955. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30303-6 [ Links ]

3. University of the Free State. Faculty of Health Sciences Rule Book. Postgraduate Degrees and Diplomas 2018. Bloemfontein: UFS, 2018. http://apps.ufs.ac.za/dl/yearbooks/317_yearbook_eng.pdf (accessed 27 June 2018). [ Links ]

4. University of the Free State. Town and Gown Programme: Building Social Cohesion Through Engagement. Draft 9. Bloemfontein: UFS, 2018. www.ufs.ac.za/supportservices/departments/community-engagement-home (accessed 27 June 2018). [ Links ]

5. Venter K, Erasmus M, Seale I. Knowledge sharing for the development of service learning champions. J New Generation Sci 2015;13(2):147-163. [ Links ]

6. Jacobs A, Venter I. Standardised patient-simulated practice learning: A rich pedagogical environment for psychiatric nursing education. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2017;9(3):107-110. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2017.v9i3.806 [ Links ]

7. Cone R. Course organization. Six models for service-learning. In: Heffernan K, ed. Fundamentals of Service-Learning Course Construction. Providence, RI: Campus Compact, 2001:2-7, 9. [ Links ]

8. Bandy J. What is service learning or community engagement? 2018. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-through-community-engagement/ (accessed 27 June 2018). [ Links ]

9. Adegbola M. Relevance of service learning to nursing education. ABNF J 2013;24(2):39. [ Links ]

10. Bada SO. Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. IOSR J Res Method Educ 2015;5(6):66-70. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-05616670 [ Links ]

11. De Swardt HC, du Toit HS, Botha A. Guided reflection as a tool to deal with the theory-practice gap in critical care nursing students. Health SA Gesondheid 2012;17(1):591. [ Links ]

12. Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: Developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med 2012;87(1):41-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.obo13e31823b55fa [ Links ]

13. Miles BM, Huberman AM, Saldaiia, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage, 2014:69-192. [ Links ]

14. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014:487-601. [ Links ]

15. Mayne L, Glascoff M. Service learning preparing a healthcare workforce for the next century. Nurse Educ 2002;27(4):191-194. [ Links ]

16. Janse van Rensburg E. A foundation for community engagement through service learning in higher education. In: Erasmus M, Albertyn R, eds. Knowledge as Enablement: Engagement Between Higher Education and the Third Sector in South Africa. Bloemfontein: Sun Media, 2014:41-61. [ Links ]

17. Colon-Gonzalez MC, El Rayess F, Guevara S, Anandarajah G. Successes, challenges and needs regarding rural health medical education in continental Central America: A literature review and narrative synthesis. Rural Remote Health 2015;15(3):3361. [ Links ]

18. Ebert L, Levett-Jones T, Jones D. Nursing and midwifery students' sense of connectedness within their learning communities. J Nurs Educ 2019;58(1):47-52. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20190103-08 [ Links ]

19. Wros P, Archer S. Comparing learning outcomes of international and local community partnerships for undergraduate nursing students. J Comm Health Nurs 2010;27(4):216-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370016.2010.515461 [ Links ]

20. Duffy A. Guided reflection: A discussion of the essential components. J Nurs Educ 2008;17(5):334-339. [ Links ]

21. Osman R, Peterson N. Service Learning in South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 2013:2-30. [ Links ]

22. Erasmus M, Albertyn, R. Knowledge as Enablement. Engagement between Higher Education and the Third Sector in South Africa. Bloemfontein: Sun Media, 2014:66. [ Links ]

23. Stewart T, Wubbena ZC. A systematic review of service-learning in medical education: 1998 - 2012. Teach Learn Med 201537(2):115-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1011647 [ Links ]

24. Berk LE. Child Development. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2000:23-38. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A C Jacobs

jacobsac@ufs.ac.za

Accepted 6 December 2019