Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.12 n.1 Pretoria Mar. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2020.v12i1.1183

RESEARCH

Exploring student persistence to completion in a Master of Public Health programme in South Africa

T Dlungwane; A Voce

PhD; Discipline of Public Health Medicine, School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Student persistence can be defined as the continuation of student enrolment and progression towards the completion of a qualification. Despite the increased number of postgraduate enrolments, attrition from postgraduate programmes is estimated at 40 - 50% in most countries globally. The throughput for Master of Public Health (MPH) programmes in South Africa (SA) ranged from 25% to 60% between 2009 and 2014. MPH students study primarily part-time and reside off campus

OBJECTIVE: To explore the phenomenon of persistence to completion in an MPH programme in SA

METHODS: A constructivist approach was adopted to understand the phenomenon of student persistence among MPH graduates. Data were collected through face-to-face in-depth interviews with graduates who completed the MPH degree between 2006 and 2014. Interviews were conducted from August 2015 to the end of October 2015. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. A thematic analysis was implemented

RESULTS: The findings indicated that personal, social, work and academic characteristics influenced student persistence to completion. Career advancement, the status that comes with an MPH qualification and being a first-generation postgraduate student provide internal and external motivations that have an impact on student persistence. An interplay between self-efficacy and social capital positively influences student persistence to completion

CONCLUSION: Student persistence to completion is influenced by multifaceted factors. Motivation, self-efficacy and social capital play a vital role in fostering persistence among part-time mature postgraduate students

Student persistence can be defined as the continuation of students' enrolment and progression towards the completion of a qualification.[1] Globally, there are a growing number of postgraduate students.[2] With the increased number of postgraduate enrolments, attrition from such programmes is estimated at 40 - 50% in most countries worldwide.[3] High postgraduate student attrition has a huge impact on national resources and robs the labour market of highly skilled personnel, resulting in loss of financial investments and knowledge.[1,4]

Student persistence to completion in undergraduate and postgraduate studies is vital for academic institutions, society and the economy.[4] Higher-education institutions are awarded funds based on the number of undergraduates and postgraduates that they produce.[4] The impact of non-completion on undergraduate and postgraduate programmes results in decreased funding and affects resource allocation.[5] Furthermore, the effect of student persistence at the societal and economic level can be observed in the production of a highly skilled workforce that is able to generate advanced and creative ideas to improve the economy and society.[6]

Student persistence to completion in postgraduate programmes is associated with factors related to students and academic institutions.[1,3] Student-related factors comprise age, time management, time from last degree, learning approaches and social connections, such as peer, family and employer.[7] Factors related to academic institutions include: mode of study, i.e. whether students are enrolled full-time or part-time, faculty support and academic integration.[1,7]

In South Africa (SA), 10 universities offer Master of Public Health (MPH) programmes. MPH students come from diverse professional backgrounds

and are primarily part-time students who reside off campus.[8] Most programmes are characterised by high attrition rates and prolonged time to completion.[9] The throughput for MPH programmes in SA ranged from 25% to 60% between 2009 and 2014.[9] The throughput for the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, SA for the cohort of students who enrolled between 2009 and 2011 and graduated between 2012 and 2014 was 25%. Although a number of students leave MPH programmes prematurely, the context for these students may not differ from that of students who persist to completion. The aim of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of persistence to completion in an MPH programme.

Methods

A constructivist approach was adopted to understand the phenomenon of student persistence to completion among MPH graduates. A case study design was implemented. Face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted with MPH graduates from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Purposive sampling was implemented by recruiting participants who were available at the time of data collection. Ten interviews were conducted until saturation was reached. Saturation refers to when no new information or themes are observed in the data.

The in-depth interviews, following the general interview-guide approach, were conducted between August 2015 and October 2015. The interview schedule was developed based on the aims and objectives of the study. The interview guide consisted of 10 open-ended questions and prompts were used. All the interviews were conducted in English. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The completeness and quality of the transcripts were verified using the observational notes taken during the interviews. The transcriptions were done by a professional transcriber and verified by the authors. The researcher (TD) read the written transcript of each participant's interview numerous times to gain a full understanding of the phenomenon and then to identify codes. A thematic analysis was implemented. Emergent themes and subthemes were derived through the coding process. Finally, a conceptual description of student persistence to successful completion of an MPH degree was developed.

Credibility through triangulation of data was achieved through individual in-depth interviews, field notes during the interviews and a self-administered questionnaire. Dependability of the collected data was ensured through an audit trail. To ensure confirmability, the principal researcher (TD) and supervisor (AV) served as peer reviewers of the individual in-depth interviews.

The interview schedule was developed in line with the objectives of the study. The interview guide consisted of 10 questions and prompts were used where necessary.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Human and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. HSS/0561/014D) and permission to conduct the study was granted by the university registrar. MPH graduates who agreed to participate in the study signed informed consent forms. These forms were filed separately to ensure anonymity. Participation was voluntary and participants were informed that they could withdraw without prejudice. The transcripts were labelled with unique numbers to ensure confidentiality.

Results

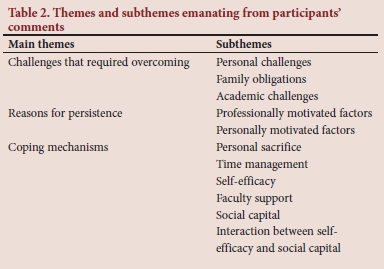

Study participants were from diverse professional backgrounds, i.e. medicine, nursing, environmental health, social science, dentistry and rehabilitation therapy. Of the 10 participants, 5 took more than the maximum permissible period for part-time studies (Table 1). Significant themes generated from the analysis of participant responses are organised and presented based on their relevance to student persistence to completion: (i) challenges that required overcoming; (ii) reasons for persistence; and (iii) coping mechanisms (Table 2).

Challenges that required overcoming

Study participants had a variety of experiences during their journey as MPH students. Challenges were experienced in the following domains: personal, family obligations and academic.

Personal challenges

Numerous personal life challenges, coupled with difficulties of being absent from higher education for an extended time, were identified as obstacles during the MPH journey:

'It was personally difficult and traumatic. I was getting divorced and getting relocated and meeting with attorneys. But it did not hinder me from actually finishing the degree. I was not going to quit - irrespective of what.' (R1) ' It was difficult, going back to studying after 6 years after completing undergraduate. During undergraduate studies I had time to myself and when I was not at university I was studying and now I have other responsibilities.' (R2)

Family obligations

Family obligations and employment demands exerted additional pressure on participants. Furthermore, these pressures were compounded by geographical distances, particularly where participants' work locations were at a distance from the family, and where both home and work locations were at a distance from the university:

My employer wanted me wholeheartedly and committed, but at the same time I had this pressure [studies] and family commitments. I had to be in three different places. My family is in [Pieter] Maritzburg, [I] work in Stanger, and my supervisor [is] in Durban. That compounded the problem.' (R8) 'It was difficult and I am working at provincial level, I do a lot of travelling. My family needed me as well. My wife was pregnant twice when I was a student and they [my family] also wanted my full attention.' (R6)

Academic challenges

Curriculum demands, dissertation challenges and institutional factors were highlighted as key academic challenges that needed to be overcome.

Curriculum demands and dissertation challenges

Difficulty in adjusting to curriculum demands and unfamiliarity with the writing style expected of MPH students were highlighted:

'I had never before written long pieces of prose where you had to develop an argument. In medical school you have very concrete things that you have to describe or regurgitate in an exam. So it [studying in the MPH] was much more difficult and much more challenging.' (R5)

Entering the dissertation phase was a challenging experience, particularly the transition from the familiar structure of coursework to working independently on the research project:

'The period when we did our modules was really nice. But when it came to the research project, that is where it started going down. Writing the research proposal was difficult; and I will send a draft and think I am finished and then the feedback comes back - have to start all over again, it was discouraging.' (R3)

Institutional factors

The inherently difficult, and often protracted, process of developing a research proposal and conducting and writing up the research were exacerbated by lengthened administrative procedures, such as delays in obtaining a supervisor and attaining ethical approval, which left students feeling helpless:

' It was frustrating. A programme that you are supposed to complete within 2 years, took me 7 years. We had few supervisors to supervise research projects for the postgraduates. The first supervisor that I was given was not interested in the area of my research study and couldn't take me through until I had a second supervisor.' (R6)

Reasons for persistence

Reasons for persisting to completion were influenced by professionally and personally motivated factors.

Professionally motivated factors

Professionally motivated reasons for persistence to completion included career changes and advancement, and expected increased marketability, credibility, and compensation:

'I felt that I needed to improve my knowledge and skills in public health management. A hospital manager or a senior manager in the Department of Health should have an MPH. By having such a degree you can become credible in what you do.' (R9)

The promise of greater remuneration was reported to have motivated persistence to completion:

' The financial factors, because when you get an MPH qualification you expect to get jobs that can pay you better than what you are currently getting or receiving in terms of salary.' (R6)

For participants, obtaining an MPH qualification was expected to open up career opportunities and further academic possibilities, including the pursuing of a PhD:

'MPH opens other doors like doing a PhD and other options in terms of career development.' (R6)

Personally motivated factors

Being part of the first generation to attain a postgraduate qualification, and setting a new standard for the next generation, provided strong motivation to complete the MPH. Completing the degree was further contextualised within previous educational frustrations, and the need to redirect aspirations. Furthermore, commitment to others as well as expectations from family, employer and supervisors, motivated students to complete their degree:

' But also there was a slight ambition at the personal level to say at least to be the first one in the family to get [a] Master's and to inspire my children.' (R8)

Coping mechanisms

Coping strategies at the personal level, such as committing to personal sacrifice and employing time-management strategies, were adopted to manage the pressures incurred by studying. In addition, self-efficacy, faculty support and social capital were identified as factors that influenced persistence to completion.

Personal sacrifice

Committing to new academic priorities required personal sacrifice, e.g. sacrificing sleep, leisure time, family time and weekend time. The commitment to personal sacrifice was a strategy used to cope with the multiple demands on their time:

' There were times where I would sit up all night finishing an assignment until five o'clock in the morning and then get ready for work and go to work. And most times it [studying] would take up my whole weekend.' (R2)

Time management

The importance of organising activities and managing time was emphasised as a key coping strategy. This involved keeping calendars, making schedules, writing timelines and developing plans and goals. All these were factors identified by respondents with their persistence to completion:

' I am very good with time-management skills. One of my children was born during the time I was studying for my Master's, and I had to develop plans and realistic goals to manage.' (R7)

Self-efficacy

In spite of challenges experienced, study participants described how tenacity, self-belief and determination to complete their degree influenced persistence to completion. Most mentioned being 'goal orientated', 'committed', 'determined', 'self-motivated', 'disciplined', and 'hard working'.

For many, it was simply refusing to quit:

'If I start something, I want to finish it.' (R9)

'... I have always believed in starting something and finishing it. I knew when I started that I needed an MPH, although there were times in my mind I had ideas of quitting.' (R4)

Faculty support

Support from administrative and academic staff was identified as a positive experience that facilitated persistence to completion:

'They [administrative staff] were excellent. That really made a big difference because we had to be attending lectures, and then you are also getting time off work. So you cannot take any extra time off to do the basics like registration functions.' (R2)

' They [academic staff] were very helpful with everything that I needed help with. [They were] very friendly, very accommodating. There was [an] open-door policy.' (R9)

Social capital

An array of informal and formal support systems was identified as essential for student persistence to completion. Having constructive employer and peer support helped students persevere and not quit in spite of the challenges:

'I had support from my employer in terms of finance and time off. I also felt [a sense of] camaraderie with the group - working together also helped and we were able to support each other a lot.' (R5) ' There was a group from the same area; we kept motivating each other throughout the degree. And the support that I received from my family, employer and supervisors kept me going.' (R3)

Interaction between self-efficacy and social capital

Regardless of the challenges experienced, students were determined to finish their degree. The interplay between self-efficacy and social capital enabled them to deal with challenges they encountered as students in the MPH programme:

'Even though it was challenging with 3 small children [and a] full-time job. I cannot start something and then not finish it. My husband supported me throughout. We supported each other - my peers. It became more like a family interaction [with peers] and academic staff were supportive. The department was accessible on weekends for group discussions.' (R7)

' There were those moments where I felt like just forget it and quit. The support and encouragement that I was getting from my supervisor, colleagues and family kept me going; I am somebody that will start something and will not leave it until I get it.' (R2)

Discussion

The high student attrition from MPH programmes prompted this study of exploring persistence to completion. Although a number of students drop out from MPH programmes, those with equally conflicting obligations have managed to complete the programme. This study sought to understand the experiences of students who have completed the MPH programme and to describe the phenomenon of persistence to completion.

The participants reported that they had to overcome a number of setbacks, spanning the personal, social, work and academic domains. The transition occurs when students complete the coursework and have to embark on a research project. The setbacks identified by participants are not unique to SA students. The factors influencing postgraduate student persistence to completion globally include: academic, financial, social and peer support[1,3]

The challenges imposed by geographical location and distances may indeed be unique in the SA context. Internal migration for employment purposes is a recognised phenomenon in SA and has historical antecedents.[10] Part of the legacy of apartheid is the spatial mismatch between where people live and where they work.[11] Working away from one's family is a widespread phenomenon in SA. If one includes the learning environment together with a different geographical location, it adds to the challenges associated with postgraduate studies.

The challenge imposed by a limited number of staff who are able to supervise Master's-level students in SA has been highlighted previously.[1] The poor supervision capacity is further exacerbated by a low number of academic staff with doctoral degrees.[12] The lack of SA academics with doctoral degrees is a major constraint regarding supervision capacity in most institutions.[12,13] A number of initiatives are currently in place to increase the proportion of academic staff with doctorates.[14] The paucity of academic staff with doctoral degrees is common in most developing countries.[12]

In the midst of the contextual challenges, the reasons foregrounded by the participants as contributing to their persistence in the MPH programme were professionally and personally motivated. The MPH degree is perceived as a qualification facilitating career progression, higher levels of remuneration and entry into leadership positions in the health sector. This is consistent with the findings from a study of 6 MPH programmes in low- and middle-income countries, where graduates' leadership positions changed and their remuneration increased after completing an MPH degree.[15]

Being the first-generation postgraduate degree holder in the family was cited as a reason for persistence to completion. Postgraduate studies are viewed as a platform to push against previous thresholds of personal achievement to motivate the generations that follow.[1,3,16] Furthermore, expectations from family, employer and supervisor encouraged persistence to completion.

Strategies to cope with the demands of part-time studies included personal sacrifice and time-management skills. Coping mechanisms adopted by mature part-time students differ from those used by full-time students.[17] This is because of the nature of responsibilities and commitments of most mature part-time students. MPH students who left the programme during the first semester reported difficulty with part-time study, which was attributed to poor time management and failure to balance work and academic obligations.[9] This implies that the curriculum in part-time programmes needs to incorporate student-development activities, such as time and stress management.[9]

This study has shown that participants' belief in their ability to complete their degree, referred to as self-efficacy, is essential to enhance perseverance despite the hurdles and setbacks. Self-efficacy is vital in ensuring persistence to completion among students who are at risk of dropping out.[18] Students who are self-motivated often see the world through a different lens, viewing experiences from a positive perspective, thus enabling them to stay motivated in spite of setbacks. Internal drive and willpower reaffirm the motivation to complete the degree regardless of the obstacles.[19]

The study participants cited that a supportive learning environment, where faculty treat them with respect and are sensitive to their needs as part-time students, contributed to their persistence to completion. Moreover, the quality of relationships that students established with peers and employers kept them motivated throughout their studies. Supportive relationships are considered important social ties and have been positively linked with student persistence to completion.[20] Healthy social networks and connections are crucial to student resilience and persistence, irrespective of challenging circumstances.[20,21]

Conceptual framework: Student persistence to completion

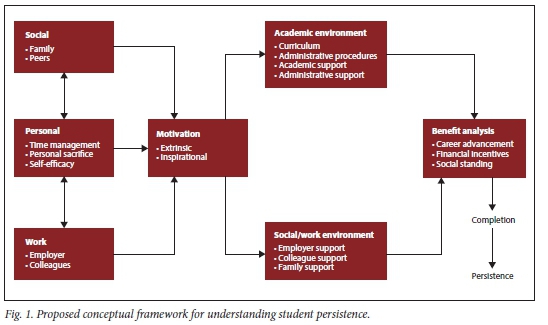

Based on a synthesis of the findings, we propose a conceptual framework explaining student persistence to completion among mature part-time MPH students. The framework views persistence as a longitudinal process in which personal, social and work characteristics influence motivation to persist (Fig. 1). Motivation is influenced by academic and social/work environments. Finally, a benefit analysis occurs where the benefit of obtaining the qualification outweighs the thought of dropping out. The benefits include career advancement, financial incentives and being a role model to future generations. Based on a discussion of the findings, a conceptual framework for understanding student persistence to completion for mature part-time students is proposed (Fig. 1).

Study limitations

This was a study of a single MPH programme and results may be transferrable to MPH programmes with mature part-time students. The study lays the foundation for a further study of a similar nature that compares MPH graduates from different settings to detect comparable or different patterns. Further research needs to be conducted to test the hypothesis proposed in the framework.

Conclusions

Student persistence to completion is influenced by multifaceted factors. Persistence to completion is the outcome of a dynamic relationship between personal, social and work characteristics that influence student motivation, which in turn influences and is influenced by academic, social and work environments. The process ultimately leads to a cost-benefit analysis where the benefit of persisting to completion outweighs the challenges that had to be overcome.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to thank the MPH graduates for participating in the study. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the US Government.

Authors contributions. TD was primarily responsible for the draft of the manuscript; TD and AV contributed substantially to the intellectual content and finalisation of the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding. This publication was made possible by grant no. R24TW008863 from the Office of the US Global AIDS Coordinator and the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health (NIH OAR and NIH ORWH).

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Koen C. Postgraduate Student Retention and Success: A South African Case Study. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape, 2007. [ Links ]

2. The association of universities and colleges of Canada: Trends in higher education. 2011. http://www.cais.ca (accessed 10 February 2016). [ Links ]

3. Herman C. Obstacles to success - doctoral student attrition in South Africa. Perspect Educ 2011;29(3):40-52. [ Links ]

4. Department of Education. National plan for higher education. 2001. http://www.education.gov.za (accessed 24 February 2015). [ Links ]

5. Scott G, Shah M, Grebennikov L, Singh H. Improving student retention: A university of Western Sydney case study. J Inst Res 2008;4(1):9-23. [ Links ]

6. Pruitt-Logan AS. Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Rev Higher Educ 2003;26(4):537-538. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2003.0032 [ Links ]

7. Chikoko V. First year Master of Education (MEd) students' experiences of part-time study: A South African case study. S Afr J High Educ 2010;24(1):32-47. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v24i1.63427 [ Links ]

8. Dlungwane T, Voce A, Searle R, Stevens F. Master of Public Health programmes in South Africa: Issues and challenges. Public Health Rev 2017;38(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0052-9 [ Links ]

9. Dlungwane T, Voce A, Searle R,Wassermann J. Understanding student early departure in a Master of Public Health (MPH) programme in South Africa. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2017;9(3):111-115. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2017.v9i3.793 [ Links ]

10. Fauvelle-Aymar C. Migration and Employment in South Africa: An Econometric Analysis of Domestic and International Migrants (QLFS (Q3) 2012). Johannesburg: African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand, 2014. [ Links ]

11. Posel D. Households and labour migration in post-apartheid South Africa. J Studies Economics Econometrics 2010;34(3):129-141. [ Links ]

12. Cloete N, Mouton J, Sheppard D. Doctoral Education in South Africa. Cape Town: African Minds, 2015. [ Links ]

13. Badat S. The Challenges of Transformation in Higher Education and Training Institutions in South Africa. Johannesburg: Development Bank of Southern Africa, 2010:8. [ Links ]

14. National Planning Commission. National Development Plan: Vision 2030. 2011. http://www.gov.za (accessed 29 July 2016). [ Links ]

15. Zwanikken P, Huong N, Ying X, et al. Outcome and impact of Master of Public Health programs across six countries: Education for change. Human Resource Health 2014;12(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-12-40 [ Links ]

16. Adams SG. Exploring first generation African American graduate students: Motivating factors for pursuing a doctoral degree. 2011. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/179 (accessed 2 January 2020). [ Links ]

17. Walters S, Koetsier J. Working adults learning in South African higher education. Perspect Educ 2006;24(3):97-108. [ Links ]

18. Cassidy S. Resilience building in students: The role of academic self-efficacy Frontiers Psychol 2015;6:1781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01781 [ Links ]

19. Taylor H, Reyes H. Self-efficacy and resilience in baccalaureate nursing students. Int J Nursing Educ Scholar 2012;9(1):1-13. https://doi.org/10.1515/1548-923X.2218 [ Links ]

20. Gasman MPR. It takes a village to raise a child: The role of social capital in promoting academic success or African American men at a black college. J Colleg Student Develop 2008;49(1):52-70. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2008.0002 [ Links ]

21. World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

T Dlungwane

dlungwane@ukzn.ac.za

Accepted 1 August 2019