Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

The African Journal of Information and Communication

versão On-line ISSN 2077-7213

versão impressa ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.32 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/ajic.i32.16018

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Mergers and acquisitions between online automobile-marketplace platforms: Responses by competition authorities in South Africa, Australia, and the United Kingdom

Megan Friday

Junior Economist, Acacia Economics, Johannesburg https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8449-4579

ABSTRACT

This study explores how competition authorities in three jurisdictions-South Africa, Australia, and the United Kingdom-have responded to proposed corporate mergers and acquisitions involving online intermediation platforms that provide automobile marketplaces. The article examines the notified (and ultimately prohibited) MIH eCommerce Holdings acquisition of WeBuyCars in South Africa; the notified (and authorised) Gumtree acquisition of Cox Media in Australia; and, in the UK, the notified (and authorised) eBay acquisition of Motors.co.uk. The author evaluates the competition considerations that came to the fore in each of these three cases and, based on these determinations, the competition authorities' decisions. The article then highlights some of the complexities that digital online intermediation platforms pose for competition authorities, and some of the possible ways in which the complexities can be managed.

Keywords: online intermediation platforms, automobile marketplaces, digital platform markets, mergers and acquisitions, competition, market definition

1. Introduction

Competition authorities worldwide are increasingly dealing with mergers and acquisitions involving online intermediation platforms. The relevant authorities are finding it challenging, inter alia, to define the relevant markets and, within these market definitions, to account for potential competitors. Such matters are of increasing concern because, in today's global, regional, and national economies, the vast majority of firms involve a digital platform element, often with an element of intermediation. The often-complex features of intermediation-platform markets need to be accounted for, and the repercussions considered, when the applicable market is assessed for the purposes of a competition authority's decision on a notified acquisition.

Online intermediation platforms present competition challenges, specifically in respect of merger control. Competition in digital markets often features "winner-takes-most" dynamics, making dominance a relatively inevitable outcome in these types of markets, which is reinforced through dynamics such as the economies of scale and strong network effects. Dominant platforms in these markets enjoy the benefits of network effects in that the more customers are attracted to their platform, the more other customers use the platform. This in turn feeds off market inertia where customers develop a propensity to use the larger platform to the disadvantage of smaller and/or newer entrants to the market. However, it may not necessarily be the case, in these markets, that firms with a large share of the market are detrimental, provided the mechanisms for market entry, and innovation by both incumbents and newcomers, are upheld (OECD, 2022, p. 19).

This study explores three cases of proposed corporate acquisition of an online automobile-marketplace platform. The cases examined were from three jurisdictions: South Africa, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Specifically, this study examined the proposed MIH eCommerce Holdings acquisition of WeBuyCars in South Africa; the proposed Gumtree acquisition of Cox Media in Australia; and, in the UK, the proposed eBay acquisition of Motors.co.uk. The focus of the South African case was primarily on the elimination of potential competition and the importance of good data to inform pricing decisions, while in Australia, the merging parties were not close competitors, and it was decided that the transaction would result in a strengthened merged entity better placed to compete against other larger rivals. The case in the UK found that merging firms were not close competitors, and thus there was no evidence that the merger would cause a significant lessening of competition.

2. Online automobile-marketplace platforms

Online automobile-marketplace platforms are used to advertise and facilitate opportunities for potential trade in automobiles between private sellers, private buyers, and vehicle dealers (seeking to both buy and sell). Some sites operate primarily as match-making platforms between sellers and buyers, while others (as in the South African case discussed in this article) go as far as buying vehicles from sellers and warehousing them while waiting for a buyer. The platforms typically charge subscription fees to dealers wanting to list multiple vehicles, and per-listing fees to private sellers who want to use the platform only once.

Intermediation platforms and multi-sided markets

In the final report of its Online Intermediation Platforms Market Inquiry, the Competition Commission South Africa (CCSA, 2023, p. 16) defines online intermediation platforms as platforms that

facilitate transactions between business users and consumers (or so-called "B2C" platforms) for the sale of goods, services and software, [including] eCommerce marketplaces, online classifieds and price comparator services, software application stores and intermediated services such as accommodation, travel and food delivery.

The platform facilitates an interaction between the buyer and seller that results in the most beneficial outcome for either side (Evans & Schmalensee, 2016). The OECD (2018, p. 10) defines a platform market as one "in which a firm acts as a platform and sells different products to different groups of consumers, while recognising that the demand from one group of customer depends on the demand from the other group(s)". The OECD (2018) also points to the fact that demands from either side of the platform market are linked to one another through indirect network effects. The platform is aware of these indirect network effects, but the buyers participating in the market are not (2018, p. 37). However, there may be additional direct network effects across the platform whereby it attracts more customers as a result of other customers using the platform.

Online automobile-marketplace platforms facilitate multi-sided markets. On the selling side, they facilitate participation by private sellers (often wanting to sell a single vehicle) and dealers (wanting to sell multiple vehicles). In many such platforms, the dealers also operate on the purchasing side (alongside private purchasers), searching for specific cars on behalf of clients and/or seeking to increase their own stock of specific vehicles that they know are popular and will sell on easily. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC, 2020a) determined that such markets are characterised by two main segments: private sellers and dealers, each representing distinct entities within the market.

It is important to recognise that firms can operate exclusively on either the supply side or the demand side of the platform, exerting influence that may impact market participants. Even if a firm is positioned solely on one side of the market, its actions can have cross-market effects, constraining other entities within the same market. These cross-market effects represent the potential impact that a single-side firm can impose on others, highlighting the interconnected dynamics that shape the market ecosystem.

An intermediary is a form of platform that follows "a horizontal model of the platform as a mediatory device enabling third party transactions to take place" (Steinberg, 2022, p. 1072). This definition requires a slight adaptation for application to the South African case discussed below, where the platform firm takes ownership of the vehicle before it is transferred over to the seller. In this case, the platform is taking a more integrated approach to involving itself in the process of matching buyers and sellers.

The role of data

Intermediation-platform firms make use of numerous types of data, including membership data, transaction data, customer behaviour data, web server data, and search engine optimisation data (OECD, 2018, p. 77). The data-based pricing mechanisms employed by online automobile-marketplace platforms account for vehicle characteristics such as make, model, year, mileage, added features, colour, and transmission type, which all influence the ultimate asking price for the vehicle. The larger players in platform markets use pricing models guided by vast amounts of data. When two large firms in the same market merge, and thus their databases merge, there is the potential for the merged firm to have a high degree of market power, because the remaining competitors in the market may simply not have access to as much data and thus may struggle to determine effective prices on the basis of which to compete.

Data can be harnessed to generate "data powered economies of scale" wherein firms with large customer bases are able to amass much more data than firms with smaller customer bases; these larger swathes of data can be used to improve the services offered by the firm; and the improved service levels encourage more customers to engage with the firm (Calvano & Polo, 2020, p. 23). One would need to consider the difference between a firm having access to or ownership over their data, as the latter could result in market failures or anticompetitive outcomes in merger and acquisition deals. Efficiently obtaining data plays a crucial role in a firm's ability to determine equilibrium prices that cater for both sellers and buyers on a platform. By gathering more data, a firm enhances its ability to accurately estimate the equilibrium price, aligning with the minimum price that is acceptable to sellers and the maximum price that buyers are willing to pay. Navigating the online automotive platforms markets may pose a challenge for firms, particularly those that may not be able to overcome barriers that could arise from needing to develop proprietary databases.

In the South African case, WeBuyCars has successfully built its databases by consolidating sales data and leveraging its control over both sides of the operational platform. With respect to data collection, while competitor firms to WeBuyCars do list the prices of vehicles online, and are able to collect that data, the data collected by the platform is not equal to the quantity and quality of data provided to the dealers and buyers of the vehicles. In the WeBuyCars platform model, the data collection and dissemination process is contained within one entity, but with alternative firms, the platform relies upon the seller or dealer providing as much factual information as possible when it may not always be in their best interest to do so. For example, when listing a vehicle that is damaged or needs a major service, dealers and private sellers will try to minimise the severity of these facts in their descriptions of the vehicle. Thus, the data that WeBuyCars can collect through its process of accepting ownership of a vehicle and providing restoration services where needed before selling to the final consumer gives it an outward appearance of trustworthiness to these final consumers. In contrast, other automotive intermediary platforms in South Africa typically offer listings without assuming ownership of the vehicles or actively participating in financial transactions, leading some consumers to doubt their trustworthiness.

Regulating competition in platform markets

In competition authority decisions, a proposed merger can receive approval if it is determined that the merger will not diminish competition in the relevant market or raise additional barriers to entry. According to Yu (2020), a central challenge for regulators evaluating mergers in platform markets is the difficulty in outlining a counterfactual scenario. Regulators are currently struggling to formulate cohesive theories of harm that accurately delineate the mechanisms causing harm to competition and also to grapple with a consistent application of economic principles to the facts of the market that they are required to assess. The capacity of a firm to impact a market is often shaped by strategic decisions regarding market entry or threat of entry. When it comes to digital platforms, the impacts of these strategic moves can be difficult to evaluate. Prohibiting firms from developing their business strategies, especially in cases where they have not yet entered the market, can be deemed unreasonable and over-reaching.

In setting out recommendations for improved merger control in digital platform markets, Calvano and Polo (2021) call for greater focus on foreclosure strategies that may be attempted by larger incumbents in relation to smaller potential competitors. These authors also recommend that competition authorities keep a more watchful eye on matters of data mobility, interoperability, open standards, and data openness in their evaluation of proposed merger transactions (Calvano & Polo, 2021). Following such recommendations could allow for better identification of potential competition concerns during the merger evaluation process and greater prevention of unilateral effects.

Cabral (2020) recommends shifting the burden of proof onto the acquiring firm to indicate the pro-competitiveness of the merger or acquisition. This reversal of the burden of proof from the authorities onto the merging parties could have the necessary effect of raising the merger-approval bar considerably. It would also allow competition authorities to engage more efficiently with the core competition matters before them in each case, rather than devoting exorbitant amounts of time to understanding the market in question. The authorities can focus on evaluating the soundness of the arguments put forward by, and seeking information from, the acquiring firm, which will always be the best-placed entity to explain the market(s) in which it is operating.

In the realm of intermediary platform markets, where the dynamics are intricate, competition authorities must tread carefully. Rather than stifling potential entrants, the focus should be on ensuring that post-merger scenarios do not create overwhelming hurdles for firms looking to gain the scale necessary to effectively compete against the incumbent(s). Consequently, decisions need to be guided by a nuanced understanding of how strategic decisions and mergers impact the competitive landscape within the intermediary platform market. Competition must be fostered, not hindered, if the market is to be dynamic and innovative.

Merger control is sometimes undermined by firms not meeting the turnover thresholds that trigger mandatory notifications to the authorities-i.e., in the platform context, when the acquired firm operating a platform is not generating significant revenue but has great potential to do so at some point in the future (Motta & Peitz, 2020). In recent years, notification thresholds have been amended in many jurisdictions, with some authorities requiring notification based on the price paid for the acquisition or based on the share-of-supply criterion, thus allowing more mergers to be assessed (Motta & Peitz, 2020).

3. Regulatory responses

South Africa: MIH eCommerce Holdings and WeBuyCars

In this case, MIH eCommerce Holdings (MIH) intended to acquire 60% of the share capital of the WeBuyCars platform.1 As MIH was controlled by the Naspers Group, the competition authorities brought into consideration other firms within the Naspers portfolio. The Naspers group already included the online automobile-marketplace platform AutoTrader,2 and another leading digital platform, Media243(Competition Tribunal, 2020b).

South Africa's Competition Tribunal ultimately decided to prohibit the proposed merger on the grounds that it would lead to significant unilateral effects through the removal of potential competition, and that it would additionally give rise to conglomerate effects (Competition Tribunal, 2020a). The Tribunal found that these conglomerate effects would ultimately further entrench WeBuyCars' existing dominance, because they would raise barriers to entry for any other actual or potential competitors. A barrier to entry existed as the merged entity would have the potential to leverage the data of the combined entity to extract maximum advantage from it, while the competing firms would not have access to this type of data at all. It was also found that there might be reciprocal benefits, flowing between the Naspers Group and WeBuyCars, which would entrench the dominance of WeBuyCars in its market (Competition Tribunal, 2020a).

The WeBuyCars platform follows a hybrid model whereby it buys vehicles from private sellers and then warehouses them until they are sold to car dealerships and private buyers. WeBuyCars was, at the time of its proposed acquisition by Naspers via MIH, also found to be making progress towards a direct business-to-customer route, facilitating direct sales to the final consumer (Competition Tribunal, 2020a).

The growth of WeBuyCars can be attributed to the rapid and early adoption of digitalisation for its platform and operations. Digitalising inventory management systems created opportunities for the business to rapidly expand and produce instantaneous statistics to guide business decision-making (PwC, 2019). It is unclear whether any other competing firms to WeBuyCars adopted similar mechanisms or digitalisation methods during this time.

In its recommendation that the merger be prohibited, the Competition Commission South Africa (CCSA) found that if the market was defined solely as a "car-buying service" then WeBuyCars had a market share above 80% (Competition Tribunal, 2020a). The Commission generated this calculation by "dividing the number of used cars that WeBuyCars purchases per month by the total number of used cars purchased across a number of competitors" (Competition Tribunal, 2020a, p. 43). Naspers, via MIH, advocated for a more broadly defined market that included all used-car dealers, traditional vehicle dealerships, and car-buying services.

In the online automotive-marketplace platform industry, the market power of a firm can to some extent be measured in terms of the number of unique leads generated by its specific platform. A unique lead arises when an individual exhibits a level of engagement with a platform that distinguishes the user from all others engaging with the same site. However, a consumer's ability to switch between different platforms skews the calculation of each platform's share of the audience, as a single viewer may be counted as a unique lead on multiple platforms. Also, it is difficult for the number of individual users on any specific platform to be calculated because the firms tend to make use of aggregated data.

In its investigation of this case, the CCSA sought to identify actual and potential competitors, and to determine the potential external constraining effects that each firm may have been imposing or may be able to impose. Identifying competitors in an online automotive classifieds market requires, inter alia, consideration of the model that each firm employs to move its stock. It was found that competitors to WeBuyCars in the South African market were offering platform services for buying and selling vehicles online, but without taking vehicles into their possession. As there were no other identical offerings in the South African market at the time of this decision, the CCSA did not comment on the constraining effects that the existing online automotive platform firms in South Africa posed to WeBuyCars.

One of the main considerations with respect to this element of the case was the volume and quality of leads. Leads are interested parties looking to buy or sell in the case of the WeBuyCars platform, or to list on one of the competing online automotive platforms available. Consumers were more likely to approach the platform that they believed would generate the larger volumes and higher quality leads to ensure they would be able to sell their car to interested buyers or have sufficient stock or listings to be able to purchase the car that they were interested in.

A critical success factor for the WeBuyCars platform, which the CCSA identified in this market, was the model in place to price vehicles. Competitors to WeBuyCars in the South African market do not have access to the same sales history, and are thus disadvantaged by the scale of data that WeBuyCars has amassed. Access to sales history enables more accurate pricing and thus higher profit margins. Weelee, a competitor to WeBuyCars, asserted that access to large amounts of pricing data was central to the case, as such access provided a competitive edge (Competition Tribunal, 2020a) and provided the first-mover with scale and network advantages over new or newer entrants (Competition Tribunal, 2020a). The sales history provides an advantage to the firm as it allows it to gain a deeper understanding of the overlap between the lowest price that the seller is willing to accept for their specific vehicle, given its specifications, and the highest price that a buyer is willing to accept to take ownership of the vehicle. A firm that has a sales history with these prices will be much more likely to accurately meet the equilibrium price that would be acceptable to both parties on either side of the platform.

In this case, it was also found that, prior to the proposed MIH acquisition of WeBuyCars, the Naspers group, controller of MIH, had taken a controlling interest in Frontier Car Group (FCG), a German-based automobile-marketplace firm. FCG had successfully entered online automotive markets in several emerging economies. It was found that, at the time of the Naspers acquisition of FCG, the Naspers recommendation committee had evidence showing FCG's intention to enter the South African market (Competition Tribunal, 2020a), which would have constituted the entry of a strong potential competitor to Naspers' MIH. The CCSA decided, and the Tribunal confirmed, that FCG would have been able to enter the South African market had it not been acquired by Naspers (Competition Tribunal, 2020a).

This acquisition was prohibited in order to prevent the entrenchment of Naspers' dominance. This case reveals that an acquiring firm's potential dominance of a market through an acquisition, coupled with evidence of the acquiring firm's removal of a potential entrant to that market, can compel a competition authority to prohibit a merger or acquisition.

Australia: Gumtree acquisition of Cox Media

In this case, Gumtree AU4 sought authorisation to acquire Cox Australia Media Solutions. Both Gumtree and Cox Media (through its online platforms Carsguide5and Autotrader6) offered online vehicle marketplaces, and, as an additional service, both offered third-party display advertising on their platforms. The ACCC found this transaction could result in increased market concentration and the removal of competition between the parties to the transaction (ACCC, 2020a). The core question in this matter was, thus, the extent of the anti-competitive effect that this merger could impose on the market as a whole. The ACCC authorised the merger (ACCC, 2020a).

The ACCC found that the market leader, Carsales,7 had significantly more total page views and time spent on its platform than did Gumtree or Cox Media. Carsales also maintained the largest inventory of total listings and generated significantly more revenue compared to its competitors. Additionally, Facebook Marketplace8 had recently entered the market and gained market share in a very short space of time, becoming increasingly competitive relative to the incumbents in the market (ACCC, 2020a, p. 24).

Vehicle dealers are incentivised to list vehicles across more than one platform in order to ensure the widest reach possible. Thus, numerous platforms seek to be one of the platforms for sellers to use alongside the market leader(s). The proposed Gumtree acquisition of Cox Media was found to place the merging parties in a better position to be dealers' secondary choice, thus making the merged entity a more effective competitor to Carsales (ACCC, 2020a). Gumtree claimed that it and Cox Media were not close competitors as Gumtree catered more for private sellers, while Cox Media's platforms (Carsguide and Autotrader) catered more for dealers' listings.

The ACCC found that Carsales, as the clear market leader, and Facebook Marketplace, as an emerging competitor, would both remain strong competitors to the merged Gumtree-Cox Media entity, and that the threat of entry would remain from other entities operating internationally. The ability of consumers to switch easily between competing platforms would also constrain rivals and encourage a competitive environment. The ACCC determined that the Gumtree acquisition of Cox Media would result in the removal of only one of the five main competitors in the market, and thus would not substantially lessen the level of competition. The ACCC also found that the merger of the two entities' online display advertising operations was unlikely to undermine competition because of, inter alia, the wide range of entities offering such services (ACCC, 2020a).

The main concern in this case was how to determine the potential anti-competitive effects of the merger. The authority had to consider how the loss of each firm's pre-merger competitive constraint would affect the market, and whether the constraining effect of the merged entity would outweigh the pre-merger effects. As neither firm in this transaction was the market leader, it was determined that the pro-competitive impact and constraining effect that the merged entity could impose on the market leader post-merger would be greater than the constraining effect that either firm could impose alone within the pre-merger market.

UK: eBay acquisition ofMotors.co.uk

In this case, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) noted that the two merging entities, eBay and Motors.co.uk,9 would not be distinct from one another post-merger. At the same time, it was noted that neither firm was the other's closest competitor, and that there were no indications that the merger would result in a substantial lessening of competition-due to the strong constraints imposed by rivals in the market and the limited increment in market position by the newly merged entity. For these reasons, the Authority approved the acquisition (CMA, 2019a).

In its evaluation of this merger, the CMA elected, in determining the closeness of competition in the market, to review service propositions, lead quality, and customer overlap. In terms of service proposition, both firms were found to be offering similar automobile-marketplace services, but with differences in their pricing models. In respect of lead quality, both firms were found to be highly established, with strong brand recognition. On the matter of customer overlap, the CMA found that each party's customer base had a greater overlap with that of AutoTrader,10 the market leader, than with each other's.

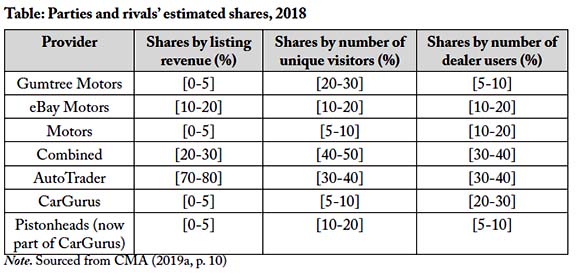

It was found that both parties to the merger had regularly referred to AutoTrader in internal documents as their main rival, with CarGurus11 referred to as the next closest competitor. The CMA's access to AutoTrader's internal documents led the Authority to understand that AutoTrader considered CarGurus a key threat. The CMA also found that the market appeared to be saturated, with many firms offering similar services. In its decision document (CMA, 2019a), the CMA provided a table of market-share estimates (reproduced below) for all the players in the sector.

The CMA table demonstrates the difficulty of discerning market shares for online automobile-marketplace platform firms, as individual measures of market share tend not to align. This complexity is pronounced in situations where consumers have the flexibility to switch between platforms. The merging parties' individual shares of listings revenue were found to be moderate in comparison to what was earned by AutoTrader, whereas the market shares in terms of number of dealer users suggested an oligopolistic market. The CMA found that the shares by revenue provided a limited amount of insight into the competitive conditions within the market (CMA, 2019a). It is evident from the figures presented above that no single measure of concentration provided a perfectly accurate reflection of the state of the market.

The CMA found that while the parties to this merger were differentiated, they were nevertheless competitors to one another pre-merger. The incremental increase in market position resulting from this acquisition would thus presumably help the merged entity to maintain competitive pressure on market leaders AutoTrader and CarGurus. The CMA also noted that buyers, dealers, and sellers found that AutoTrader was expensive to list on, thus potentially encouraging the use of other platforms (CMA, 2019a).

The CMA found AutoTrader to be the main competitive constraint on the merging parties, based on dealers allocating the largest portion of their spending to its platform, with the remainder of their spending divided among the other players in the market. The CMA concluded that if the dealers felt that firms in the remainder of the market could generate sufficient leads from consumers, they might be inclined to divide their spending more evenly among the competing firms (CMA, 2019a). The CMA thus determined that the loss of potential competition that each of eBay and Motors.co.uk could impose on the market individually was outweighed by the gain in competitive constraint that the new merged entity could impose (CMA, 2019a).

4. Analysis

The South African case demonstrates a finding that a firm attempting to enter a market that it could reasonably enter and compete in by itself should not be allowed to acquire the incumbent leader of that market, as such an acquisition would result in a reduction of the constraining effect that potential competition imposes on a market. This case focused on the dominant position of the target firm in light of the position of the acquiring firm. Several questions were also raised about the importance and advantage of access, post-merger, to strategically important data. The other two cases, in Australia and the UK, demonstrate findings that even though the potential competition that each of two merging firms could impose on the market will be lost, it will not have an anticompetitive result due to the newly merged entity being able to provide a greater constraining effect on the market leader. This shows how the potentially anti-competitive effect of an increase in market concentration caused by a merger can be outweighed by the heightened competitive constraint resulting from the merger. Authorities' concerns around increased levels of concentration tend to be subdued in cases where a merged entity will provide a more effective competitor to a dominant market leader.

From the review of the three cases presented above, two different types of transactions emerge. In the South African case, there was an acquiring firm attempting to purchase the leading incumbent in the market so as not to exert the effort and capital required to enter the market based on competitive merits. In the Australian and UK cases, two firms that already operated within the same market merged with one another in an effort to provide a stronger competitor to the market leader, thus potentially increasing the level of competitive constraint they could exert on the market leader, relative to their competitive significance as individual firms.

Given the rapid increase in digital or technological firms merging or acquiring one another, many new competition elements are arising. Policies and regulations are not able to evolve as rapidly as digital intermediary platforms. Thus, courts and competition authorities are finding it challenging to address the competition issues that arise in technology-driven markets. Yu (2020) warns that decisions, made in potential competition cases, that are based on purely legal standards result in under-enforcement. This under-enforcement, as a result of legal standards not being able to keep pace with the growth of technology and new technology-enabled markets, results in a reduction of consumer welfare.

There is a great need to integrate platform economics more robustly as authorities assess these transactions. In the three cases considered here, the decisions were based on the established consideration of the loss of potential competition; the closeness of competition between the merging firms; and the state of competition in the market post-merger. The South African case introduces a data perspective that prompts significant economic questions, yet to be fully explored. The competition authorities should keep in mind the crucial role that extensive datasets play in mitigating uncertainty related to the pricing dynamics of a platform business.

Across the three cases discussed above, we see competition authorities apparently succeeding in adapting to the new digital-platform market environment. But there can be little doubt that there are numerous potentially anti-competitive merger and acquisition cases involving digital platform markets, in various national jurisdictions around the word, that have received sub-optimal scrutiny, or no scrutiny at all, from competition authorities.

5. Conclusions

As globalisation and technological advancements persist, an increasing number of industries are incorporating digital elements into their service or product offerings. This trend is giving rise to heightened digital competition issues. To address this evolving landscape, regulatory authorities must anticipate and understand the challenges that are present.

This study has focused on contributing to the comprehension of the regulatory dimensions related to competition dynamics in online intermediation platform markets. The findings reveal two distinct scenarios. The first, exemplified by the WeBuyCars case in South Africa, involved the competition authorities blocking a holding company associated with an existing firm from entering the market, foreseeing potential competition deficiencies. In the second scenario, observed in the Australian merger of Gumtree and Cox Media, and the UK merger between eBay and Motors.co.uk, competing forces were allowed to merge so as to enhance their competitiveness against the market leader(s).

Going forward, it can be anticipated that there will be an increased frequency, of competition investigations regarding digital platform markets. In those investigations, control of data held by merged firms will no doubt be a core dimension requiring close scrutiny-and requiring effective remedies from competition authorities when data control has the potential to enable anti-competitive behaviour.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on content from the author's Master of Commerce research and thesis at the University of Stellenbosch (Friday, 2022). The author presented elements of this article in a paper delivered to the 7th Annual Competition and Economic Regulation (ACER) Week conference, 15-16 September 2022 in Senga Bay, Malawi, which was convened by the COMESA Competition Commission, the Competition and Fair Trading Commission of Malawi, and the University of Johannesburg's Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED). AJIC is grateful for the internal reviewing support provided for this article by CCRED Director Dr. Thando Vilakazi, who is also a member of the AJIC Editorial Advisory Board.

References

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). (2019). Digital platforms inquiry: Final report, https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/digital-platforms-inquiry-final-report

ACCC. (2020a, April 30). Gumtree AU Pty Ltd proposed acquisition of Cox Australia Media Solutions Pty Ltd. https://www.accc.gov.au/public-registers/mergers-registers/merger-authorisations-register/gumtree-au-pty-ltd-proposed-acquisition-of-cox-australia-media-solutions-pty-ltd

ACCC. (2020b, May 19). Views sought on issues for draft media and digital platformsbargaining code [Media release]. https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/views-sought-on-issues-for-draft-news-media-and-digital-platforms-bargaining-code

Belleflamme, P., & Peitz, M. (2010). Industrial organisation: Markets and strategy. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511757808

Cabral, L. (2020). Merger policy in digital industries. Information Economics and Policy, 54, 100866, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2020.100866 [ Links ]

Calvano, E., & Polo, M. (2020). Market power, competition, and innovation in digital markets: A survey. Centre for Economic Policy Research.https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3523611

Calvano, E., & Polo, M. (2021). Market power, competition, and innovation in digital markets: A survey. Information Economics and Policy, 54(March), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2020.100853 [ Links ]

Competition Commission South Africa (CCSA). (2020). Competition in the digital economy: Version 2. https://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Digital-Markets-Paper-2021-002-1.pdf

CCSA. (2023). Online intermediation platforms market inquiry: Final report and decision. https://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/CC_OIPMI-Final-Report.pdf

Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). (2019a). Anticipated acquisition by eBay Inc of Motors.co.uk Limited: Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition. Case No: ME/6774/18. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5c82485b40f0b63694ab9c2b/full_text_decision.pdf

CMA. (2019b). eBay Inc / Motors.co.uk. Limited merger inquiry. Case No: ME/6674/18. https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/ebay-inc-motors-co-uk-limited-merger-inquiry

Competition Tribunal. (2020a). MIH eCommerce Holdings (Pty) Ltd and We Buy Cars (Pty) Ltd. (LM183Sep18). https://www.comptrib.co.za/case-detail/8539

Competition Tribunal. (2020b, March 27). Tribunal prohibits Naspers' planned merger with WeBuyCars. https://www.comptrib.co.za/open-file?FileId=52256

Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. (2016). Matchmakers: The new economics of multisided platforms. Harvard Business Review Press.

Friday, M. (2022). The law and economics of potential competition in digital markets: Case studies in online intermediation platforms [Master's thesis.]. University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. [ Links ]

Motta, M., & Peitz, M. (2020). Removal of potential competitors - a blind spot of merger policy? Competition Law & Policy Debate, 6(2), 19-25. https://doi.org/10.4337/clpd.2020.02.03 [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Rethinking antitrust tools for multi-sided platforms, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/rethinking-antitrust-tools-for-multi-sided-platforms.htm

OECD. (2022). OECD handbook on competition policy in the digital age. https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition-policy-in-the-digital-age/

PricewaterhouseCoopers.(PwC) (2019). WeBuyCars: Used car retailer fuels growth through digitalisation. In Africa private business survey 2019 (p. 12). https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/entrepreneurial-and-private-companies/emea-private-business-survey/pwc-emea-private-business-africa-report-2019.pdf

Rochet, J. C., & Tirole, J. (2006). Two-sided markets: A progress report. The RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3), 645-667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00036.x [ Links ]

Steinberg, M. (2022). From automotive capitalism to platform capitalism: Toyotism as a prehistory of digital platforms. Organisation Studies, 43(7), 1069-1090. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406211030681 [ Links ]

Wu, T. (2010). The master switch: The rise and fall of information empires. Atlantic Books.

Yu, J. M. (2020). Are we dropping the crystal ball? Understanding nascent and potential competition in antitrust. Marquette Law Review, 104(3), 613-660. [ Links ]

1 https://www.webuycars.co.za

2 https://www.autotrader.co.za

3 https://www.media24.com

4 https://www.gumtree.com.au

5 https://www.carsguide.com.au

6 https://www.autotrader.com.au

7 https://www.carsales.com.au

8 https://www.facebook.com/marketplace

9 https://www.motors.co.uk

10 https://www.autotrader.co.uk

11 https://www.cargurus.co.uk