Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The African Journal of Information and Communication

On-line version ISSN 2077-7213

Print version ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.31 Johannesburg 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/ajic.i31.14518

RESEARCH ARTICLES

"If it is circulating widely on social media, then it is likely to be fake news": Reception of, and motivations for sharing, COVID-19-related fake news among university-educated Nigerians

Chikezie E. UzuegbunamI; Chinedu Richard OnoniwuII

ILecturer, School of Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3958-5494

IIPhD candidate, Department of Mass Communication, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2900-5561

ABSTRACT

This study explores how university-educated Nigerians living in two urban centres engaged with, and made choices about whether to share or not share, "fake news" on COVID-19 in 2020. The research adopted a qualitative approach by conducting focus group interviews with participants, all university graduates aged 25 or older, sampled from Lagos and Umuahia-two major metropolitan cities in Nigeria. Participants' sense-making practices with regard to fake news on COVID-19 were varied. One core finding was that social media virality was typically seen as being synonymous with fake news due to the dramatic, exaggerated, and sometimes illogical nature of such information. Many participants demonstrated a high level of literacy in spotting fake news. Among those who said that they sometimes shared fake news on COVID-19, one motivation was to warn of the dangers of fake news by making it clear, while sharing, that the information was false. Other participants said that they shared news without being certain of its veracity, because of a general concern about the virus, and some participants shared news if it was at least partially true, provided that the news aimed to raise awareness of the dangers of COVID-19. However, some participants deliberately shared fake news on COVID-19 and did so because of a financial motivation. Those who sought to avoid sharing fake news on COVID-19 did so to avoid causing harm. The study provides insights into the reception of, and practices in engaging with, health-related fake news within a university-educated Nigerian demographic.

Keywords: fake news, misinformation, disinformation, COVID-19, social media, news media, reception, sense-making practices, Nigeria, Lagos, Umuahia

1. Introduction

Social media "fake news" has been a major source of concern in Nigeria ever since the 2015 general elections. During those elections, there was a growing population of internet users, with online and social media playing an active role in citizens' vigorous political participation-and, at the same time, providing fertile ground for politicians to disseminate amplified, partisan, and distorted messages (Ogwezzy-Ndisika et al., 2023). The 2015 general elections in Nigeria were conducted at a time when the use of social media in electioneering and political participation was becoming steadily more popular, following the inaugural use of social media in the preceding elections of 2011 (Uzuegbunam, 2020). Concerns about social media fake news have since escalated to the extent that most of the ensuing political, social, and economic problems present in the country have to some extent been attributed to it (Adegoke & BBC, 2018; Anderson, 2019).

In addition to the threat that fake news poses to Nigeria's peace, unity, security, and positive international reputation, it also poses particular challenges in relation to its healthcare system, which is hampered by problems of infrastructure, policy, and outdated health beliefs, all of which have contributed to disease outbreaks (Welcome, 2011). Health-related fake news can delay or prevent effective care and, in some cases, threaten the lives of individuals, i.e., people misled by fabricated messages. Stated differently, the problem of health-related fake news becomes consequential when news consumers do not recognise a particular news item as fabricated and respond to it as true (Lara-Navarra et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). In the Nigerian context, research has found that individuals who rely on social media platforms as their main source of news tend to be more likely to believe fake news on health issues such as COVID-19 (Uwalaka, 2022).

The term "fake news" is somewhat contested in communication scholarship. Allcott and Gentzkow (2017) conceptualise fake news as being intentionally and verifiably false, and, at the same time, potentially deceptive to audiences. Gelfert (2018) argues that fake news should be seen as but one category of "false news". Given that even reliable news sources can occasionally make mistakes, Gelfert (2018) believes that the definition of fake news as news that contains inaccurate information is inadequate, because a justifiable mistake about an irrelevant or incorrect detail does not necessarily render the entire report fake news. For Gelfert (2018), fake news is a deliberate attempt by the originators to deceive an audience, to manipulate public opinion, and to increase the circulation of false information. Accordingly, Gelfert (2018) defines fake news as the "deliberate presentation of [...] false or misleading claims as news, where the claims are misleading by design' (pp. 85-86, italics in original). Lilleker (2018) is also of the view that fake news is news that is deliberately misleading. These definitions seem to equate fake news with "disinformation" (false information created and spread with the intention to mislead), but, in our analysis, fake news is more usefully understood as comprising both disinformation and "misinformation" (false information created and spread without an intention to mislead, or without concern as to whether the information is false or not).

Both terms, disinformation and misinformation, are widespread in the academic literature on manifestations of false information, or what is also sometimes referred to as "information disorder" (see Wardle, 2019). In our research and this article, we use the term "fake news" to refer to any kind of false information circulating in the various media channels, including social media, regardless of whether the false information's creation, or distribution, is performed with the intent to mislead, i.e., all false information, including the intentionally misleading subset that is disinformation, can constitute fake news if disseminated via some sort of media platform. Our definition of fake news aligns with the definition used in the Madrid-Morales et al. (2021) article on sharing of misinformation, in which it is stated that that the terms "misinformation" and "fake news" are used "interchangeably to refer to all the expressions and formats in which made-up and inaccurate information has been found to be common" (p. 1201, footnote).

For Choy and Chong (2018), fake news has lexical features that are different from those of factual reports. For example, as they explain, biased information has been associated with specific linguistic cues, including active verbs, implicative verbs (verbs such as "manage to" and "bother to", which suggest that the "truth value" of a clause is conditional), and subjective intensifiers (such as "extremely" and "utterly"). Choy and Chong point to "clickbait"-a type of deceptive online content that uses special lexical elements like emotional language, action words, suspenseful language, and the overuse of numerals. The authors argue that since fake news has unique lexical features, these features can be used to detect its presence in online news content. The authors also argue that deceivers (creators of fake news) tend to tell less complex stories. When compared to the stories of truth tellers, deceivers' messages show lower cognitive complexity. Thus, these deceptive messages have lower average sentence length and lower average word length (Choy & Chong, 2018). The messages also tend to make frequent use of motion verbs such as "walk", "move", and "go", as these provide simpler and more concrete descriptions than words that focus on evaluations and judgments (such as "think" and "believe"). With respect to the affective dimension of fake news, Choy and Chong (2018) contend that those who fabricate fake news do so with a view to appealing to the audience's emotions.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has reignited global interest in the discourse around health-related fake news, further deepening investigation into its implications for public health. Commenting on how online fake news has worsened the spread of COVID-19, the Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, noted that the world is faced with both a pandemic and an "infodemic"-a deluge of all manner of information, including both factual and inaccurate information, in offline and online spaces, during a disease outbreak or health crisis. Online fake news on COVID-19 has had serious impacts in parts of the world. For instance, it was responsible for deaths in Iran in March 2020, when 2,100 Iranians ingested methanol (a toxic industrial form of alcohol) after exposure to social media messages that suggested alcohol consumption could prevent infection by the virus (Soltaninejad, 2020).

In this study, we specifically explored the reception of, and motivations for sharing (or not sharing) fake news on COVID-19 in Nigeria. Here, "reception" refers to how information is interpreted and made sense of by its recipients. We draw from reception studies and thereby view "reception" as the participants' reactions to fake news (Sandikci, 1998; Wagner & Boczkowski, 2019). "Motivations", in this study, refer to the reasons or determinant factors behind recipients' decisions to share or not to share fake news.

Research aims and questions

This study sought to make a scholarly contribution in the areas of both social media reception and health communication. The aim was to empirically assess how selected cohorts of university-educated Nigerians in urban locations responded to COVID-related social media fake news, and the extent to which they shared such news. The study was grounded in two core questions:

• How do university-educated Nigerians receive and interpret fake news on COVID-19 issues?

• What are their motivations for sharing (or not sharing) fake news on COVID-19 issues?

2. Reception of, and motivations for sharing, fake news

The reception of, and motivations for sharing, fake news have both drawn significant research attention. In their Nigerian research on the role of misinformation in undermining the containment of Ebola, Allgaier and Svalastog (2015) highlight instances where the audience received false information on the virus as true. The authors cite accounts of people dying and being admitted to hospitals in Nigeria as a result of audience adoption of incorrect information about dangerous methods of combating Ebola. Also looking at factors influencing the sharing of health-related misinformation, Aquino et al. (2017) identify anti-vaxxers as major sources or propagators of misinformation. These authors find that discussions among this category of audience tend to revolve around rhetorical as well as personal arguments that induce negative emotions such as anger, fear, and sadness.

Chua and Banerjee (2017) examine the role played by epistemic belief in affecting people's decisions regarding whether or not to spread health-related rumours online, and the authors discover that people who are "epistemologically naïve" are more likely than "epistemologically robust" people to share health-related misinformation online. For Chua and Banerjee (2017), epistemologically naïve people are those who believe that knowledge is relatively rigid and easily attainable. Conversely, as noted by Chua and Banerjee (2017), people who believe that knowledge is largely fuzzy and requires significant effort to obtain are epistemologically robust. The foregoing would suggest that epistemologically naïve people are more likely to receive (and share) fake news uncritically, while the epistemologically robust will more easily identify (and not share) fake news.

Chakrabarti et al.'s (2018) study in five cities in Kenya and Nigeria identified two main categories of motivations for sharing fake news. First, individuals share fake news due to their desire to be seen as "in the know" socially, with such sharing viewed as a path to gaining social currency. Second, a sense of civic duty leads some users of social media to share warnings of, and to inform others of news received on, an imminent danger-irrespective of whether the sharer thinks the news is reliable or not. Chakrabarti et al. (2018) found an assumption among sharers that it is preferable to tell people widely just in case the information could benefit them, on the grounds that if the information about a supposed imminent danger turns out to be false, no substantial harm will be caused. However, if the information turns out to be accurate, it can have significant practical advantages for many.

The aforementioned study by Madrid-Morales et al. (2021) looked at motivations for sharing misinformation online among university students in six African countries. The study found two key motivations among this demographic. First, participants share out of a sense of civic duty, where they feel they have to warn others of inherent dangers. Second, they share misinformation for the fun of it, in order to elicit laughter or humour. Another study, by Wasserman and Madrid-Morales (2019), establishes a link between lack of trust in the news media and the sharing of fake news. In a survey of 1,847 Kenyans, Nigerians, and South Africans, a significant relationship was found between high levels of perceived exposure to misinformation and low levels of media trust. This corresponds with similar findings elsewhere (see Chadwick and Vaccari (2019) in the British context) that suggest that the widespread sharing of false news may signify a growing cynicism towards the accuracy of news in general. In their study conducted in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Miami, Wagner and Boczkowski (2019) found that a general mistrust and scepticism regarding the veracity of the news ecosystem as a whole is linked to the consumption and sharing of fake news.

In parts of Africa, cultural influences, including the long-standing importance of informal sources of information such as gossip, rumour, and satire (Madrid-Morales et al., 2021; Nyamnjoh, 2005) can often play a role in the tendency for social media users sharing fake news. In addition to these cultural influences in the African context, the long history of untrustworthy news media on the continent, and of muzzled media environments controlled by the state or socioeconomic elites, has given rise to strong alternative channels of information on which fake news can thrive (Wasserman & Madrid-Morales, 2019). A study by Tully (2021) of how Kenyans experience misinformation found that the participants' consumption and sharing of misinformation is determined by their personal interest in a particular topic, the extent to which it trends within their social networks, and the perceived importance of the information.

The motivations for sharing information, including false information on social media, can also be psychological or emotional. Drawing from data from cross-sectional surveys in the US, Petersen et al. (2023) argue that psychological motivations underpin the sharing of hostile political rumours, a form of false news, as participants in their study felt a personal burden to challenge the political system as a whole and to mobilise receivers of such messaging against a particular political setting. Dafonte-Gómez's (2018) study finds that some sharing practices are motivated by affective connections and emotions because of the heightened emotion they feel while interacting with viral news on social media.

Furthermore, other scholars have found that the social identity of the audience is a factor that can influence their sharing of information on social media. Bigman et al. (2019), in their online survey of 150 college students of black, white, and "other" races/ethnicities in the US, found that race influences how young social media users selectively expose themselves to news on social media. Black students, more so than the students of other races/ethnicities, reported seeing and posting race-related content on social media. Bigman et al. (2019) also found an orientation towards civic participation or civic purpose as a motivation for sharing information on social media.

Other studies have found that the main motivation for fake news production and dissemination is commercial (Hirst, 2017; Marwick & Lewis, 2017), with creation and dissemination of misinformation used to boost traffic to an online site and increase advertising revenue (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). This phenomenon was witnessed during the 2016 US elections when a group of teenagers in Macedonia created fake news for economic gain. Sharing pro-Trump content, even when it contained falsehoods, generated online traffic that helped them to make money through advertisements (Marwick & Lewis, 2017).

While the above review shows that there have been numerous studies of audiences' reception of, and motivations for sharing, fake news, few studies in African settings have focused on how people in certain narrow demographics receive, and decide whether to share, such information. This study fills this research gap, in the Nigerian context, with a focus on the consumption and sharing behaviours of university-educated individuals in two urban settings.

3. Research design

This study adopted a qualitative approach, using focus groups with 60 individuals (all of whom were university graduates) aged 25 and above living in Umuahia and Lagos-two metropolitan cities in the south-eastern and south-western parts of Nigeria, respectively. The decision to focus on these two cities was based on their socioeconomic significance. Umuahia is one of the major commercial hubs of Nigeria's South East Region, and Lagos is the largest hub for the corporate and entrepreneurial sector in Nigeria. Both cities are thus strategically positioned and have residents drawn from various parts of the country.

Focus group discussion was chosen as an appropriate data collection method because it suits research that seeks to explore complex issues and to collect in-depth data at minimal cost (Brennen, 2012; Carey, 1994). A total of ten focus groups were conducted-five in each city-between August and October 2020. Each consisted of six participants. The study participants were gathered through a snowball technique where initial reliable contacts generated further contacts. Seven of the 10 focus groups had a 50:50 gender ratio (three males and three females) and the gender ratios of the other three groups were 40:60 for the males and females, respectively.

Each focus group lasted for approximately 90 minutes, and explored participants' reception of, and motivations for sharing (or not sharing), fake news on COVID-19 issues (see Appendix for the focus group discussion protocol). The focus group discussions explored questions such as: how media users would define fake news on COVID-19; how they identified false stories on COVID-19 when they saw them; the forms of media they saw as most likely to carry false or accurate information on COVID-19; and their views on how the media reported the pandemic.

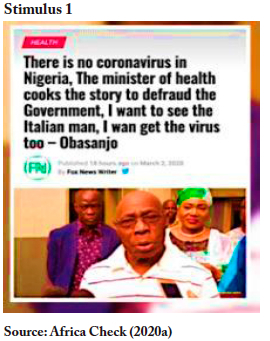

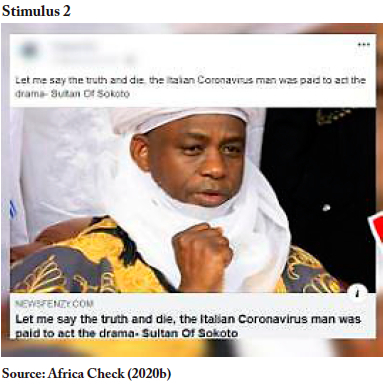

Participants were also asked what their reactions would be if they saw certain instances of fake news on their social media timelines; whether they would share such stories; and their motivations for sharing or not sharing. To elicit detailed responses, participants in each focus group were presented with four stimuli. The stimuli were screenshots of online news headlines and lead paragraphs on COVID-19 identified as fake by Africa Check, an independent fact-checking organisation, headquartered in Johannesburg (Cox, 2013). The participants were not informed beforehand that the stimuli had been confirmed as fake news by Africa Check. This was to allow them to make sense of the stimuli on their own. The four stimuli are presented in the Appendix. Stimulus 1 showed a fake news item where former Nigerian president, Olusegun Obasanjo was quoted as saying that there was no COVID-19 in Nigeria (Africa Check, 2020a). Stimulus 2 showed a fake news item where the Sultan of Sokoto argued that the first case of COVID-19 in Nigeria (an Italian national) was faked by an actor (Africa Check, 2020b). Stimulus 3 showed a fake news item where garlic was presented as a cure for COVID-19 (Africa Check, 2020c). In Stimulus 4, a false record of COVID-19 cases in Nigeria was presented (Africa Check, 2020d).

The researcher who organised the focus groups (Ononiwu), or a research assistant trained for this purpose, mediated and audio-recorded each discussion session. Participants were given consent forms and information sheets before each of the focus group meetings commenced, and they were given the opportunity to ask questions about their involvement in the study. Before participants agreed to participate, and signed the consent forms, they were informed about the study's objective and significance, as well as the methodology and how the qualitative data would be used.

The qualitative data from the 10 focus groups was transcribed word-for-word and analysed thematically. Before the thematic coding, we listened to each audio recording and double-checked the transcripts for accuracy. We also took note of the responses' frequency, context, and specificity. Within each focus group, this method allowed for the identification of patterns, themes, and contradictions. In addition, quotations that best reflected the primary topics were chosen as part of the data analysis below. Two academic colleagues read the data independently and recognised themes that were similar to the ones we identified, ensuring the study's validity. We limited access to the data and provided secure data storage to guarantee confidentiality.

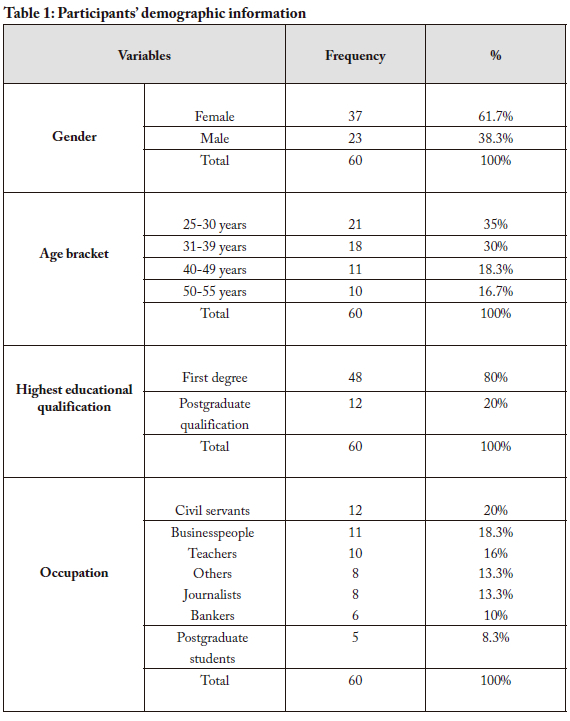

In addition to taking part in a focus group discussion, each participant was requested to indicate their gender, age, highest educational qualification, and occupation (as summarised in Table 1).

4. Findings and analysis

In this section, the results of the analysis of the qualitative data are discussed under two broad themes:

• reception of fake news on COVID-19; and

• motivations for sharing, or not sharing, fake news on COVID-19.

Reception of fake news on COVID-19

Participants in eight of the 10 focus groups claimed that they knew news was likely to be fake when it was going viral on social media and it was dramatic, exaggerated, and illogical when juxtaposed with well-known events. In the words of a participant in one of the Lagos focus groups:

If it is circulating widely on social media, then it is likely to be fake news. Fake news on COVID-19 has elements that make it appealing and therefore likely to spread quickly. Fake news is sensational. It is also exaggerated. How can someone tell you that 1,000 persons are infected with the virus but when you look around, you cannot find anyone you know who has the virus? (male businessperson, age 44, Lagos).

According to another Lagos participant:

We all know that the number of persons peddled online is far more than the actual number infected by the virus. COVID-19 does not affect us here as much as it affects people from other countries, especially in the West. The figures we see online are from fake news. Where is this 472 confirmed cases coming from [referring to Stimulus 4]? (male civil servant, age 41, Lagos).

Participants in six of the 10 focus groups (two in Lagos, four in Umuahia) saw social media as a natural home for fake news on COVID-19, saying that most COVID-19 information that was disseminated virally on WhatsApp and Facebook was fake. In the words of one of the Umuahia participants:

News {items] on WhatsApp and Facebook are the major culprits. You can hardly see information on these platforms that is not fake. Credible news channels seldom use these platforms effectively. What people do is pick information from somewhere, modify it and spread [it] mostly on Facebook to attract more engagement for their social media pages (female teacher, age 33, Umuahia).

According to one of the Lagos participants:

Fake news on COVID-19, as spread on social media, is designed to draw enormous public attention. This is why it spreads every quickly. It is like gossip, it is exciting. For instance, when it was alleged that cow urine could cure COVID-19, you can tell it is fake. Cow urine? Does it make common sense? Then look at this one that says garlic cures COVID-19 [referring to Stimulus 3]. It is unsubstantiated. People who post these things just want to cause a stir (male banker, age 30, Lagos).

The foregoing responses point to the widely held view among the respondents that there was a great deal of deliberateness in the development and posting of COVID-related fake news-deliberateness that has also been identified by Gelfert (2018).

Participants in six of the focus groups (four in Lagos, two in Umuahia) stated that fake news on COVID-19 was often identifiable through its use of information that was contrary to what had been presented by media entities that the participants described as credible, such as BBC and CNN, or contrary to information provided by health bodies such as the WHO:

Fake news on COVID-19 always presents what is different from what reputable organisations like WHO says (female businessperson, age 25, Lagos).

It presents information contrary to what the reliable news outlets are presenting. When I talk about reliable news outlets, I am talking about BBC and CNN (male civil servant, age 30, Umuahia).

If a particular news [item] is showing something different from what you saw somewhere, then there is something suspicious about it. This is quite different from when a news source tries to get another angle of the same story. What I mean here is that fake news is outrageously different from what other [more credible] sources are saying (male civil servant, age 38, Umuahia).

Health organisations such as the World Health Organisation and the NCDC [Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention] are giving us the factual figures. Credible news organisations are relying on NCDC for factual information, especially figures on the number of new cases and discharged people. However, fake news does not present these facts. You see all sorts of figures [from non-credible sources] (male postgraduate student, age 31, Lagos).

Two of the focus group participants in Lagos identified the following additional elements that helped them to distinguish between fake and credible COVID-related news:

There are a lot of spelling and grammatical errors in fake news about the virus. Those that write this fake news are not professional journalists. Their intention is to create things that can spread quickly on social media, so they come up with all sorts of things [...]. The news is usually scattered. [...] There is little or no editing. This is quite different from what you would expect from an established media outlet (male postgraduate student, age 29, Lagos).

It is easy to spot. Fake news on COVID-19 is sometimes written haphazardly. You cannot trace it to any source. The writers are usually unknown. You know when you read the newspaper, you can see the name and contact address of the person that wrote a particular story. But this is not the case in fake news. You just see the story with no name, no byline. You cannot do that in ethical journalism. It is not our standard. Fake news also lacks accuracy. The content is really questionable. Look at this [referring to Stimulus 2]. I do not think the Sultan can say something like that. He cannot use words like "let me say the truth and die" (female journalist, age 54, Lagos).

At the same time, some participants in one of the focus groups in Umuahia were of the view that it was not possible to draw a line between fake news and factual news on COVID-19:

Every news basically looks the same to me. There is no way to know which one is fake, unless there is some other thing you know behind what is presented in the news or on a personal level. It is a difficult one. News na news ["all news is the same"] (female businessperson, age 50, Umuahia).

I do not even know. I cannot tell which one is fake and which one is not. All sorts of things are just flying around (male civil servant, age 31, Umuahia).

You cannot tell the real one from the fake one. For me, everything is fake (female civil servant, age 40, Umuahia).

Distrust of the Nigerian news ecosystem

Participants in two focus groups (one in Lagos, one in Umuahia) spoke of a lack of trust in the Nigerian news ecosystem, whether on social media platforms or on the platforms of Nigerian media outlets. When asked which type of media was more likely to carry factual news about COVID, a participant in Lagos said:

I cannot really say as far as Nigeria is concerned because everything here is fake. If you really want something factual, you can rely on international media (female civil servant, age 40, Lagos).

In the words of another participant:

There are a lot of manipulations everywhere. The Nigerian media is filled with manipulated stories with different motives and interests (female banker, age 30, Umuahia).

One participant pointed particularly at the government-owned media as the major source of fake news on COVID-19:

I think it is government-owned media. I do not really trust them. They are working for the government and come up with a lot of things to suit the government's agenda (male banker, age 30, Umuahia).

According to another participant:

For me, I really don't think any of this news [is] true. There is something manipulated in all of them. This is how I feel. I think even the ones coming from the government are manipulated for one purpose or the other. Some things are not said exactly the way they are by the government and other stakeholders (female banker, age 30, Lagos).

These sentiments resonate with the findings of other studies on general distrust of, and cynicism towards, all forms of news media (Chadwick & Vaccari, 2019; Madrid-Morales et al., 2021; Wagner & Boczkowski, 2019; Wasserman & Madrid-Morales, 2019), with such cynicism found, in some cases, to make people more likely to spread misinformation.

COVID-19 denialism

The participants in one of the focus groups in Umuahia expressed doubts about the seriousness-and in some cases even the existence-of the virus:

Most of the news [items] in this country on COVID-19 are fake because they seem to present the virus as very serious. Personally, I do not feel the virus is very serious in this part of the world. We all know that it does not kill an African man. I think the government is just giving figures about cases of infection and death just to get money from international organisations (male civil servant, age 31, Umuahia).

I think most news on COVID-19 is fake because I know that the virus does not exist. In the first years of HIV, I saw HIV patients with my eyes. It is real when you see someone that has it. But for COVID-19, as far as Nigeria is concerned, it is all fake (female civil servant, age 40, Umuahia).

Motivations for sharing, or not sharing, fake news on COVID-19

Desire to warn of the dangers of fake news

Participants in three of the focus groups (two in Umuahia, one in Lagos) spoke of sharing fake news but at the same time making people aware that it was fake, thus seeking to perform a public service. In the words of a Lagos participant:

Yes I would share with a caption explaining the dangers of fake news on COVID-19 and air my views about the situation from the point of knowledge about the facts (female dentist, age 50, Lagos).

An Umuahia participant who identified as a journalist explained his actions in this way:

I share fake news as background to my own factual information on the dangers of COVID-19 and how people can take precaution. Since I am really interested in making people aware of the possible dangers of the virus, then I have to attach something factual just like I said earlier. Sharing the fake news as it is cannot create awareness on the possible dangers of the virus without attaching some reliable information before sharing. For instance, when there was a fake news that chloroquine could cure the virus, I shared the news and added some facts as caption. I then concluded by encouraging people to present themselves to health facilities each time they noticed corona symptoms (male journalist, age 41, Umuahia).

These findings appear to add nuance to the findings of Chakrabarti et al. (2018) on sharing information based on a sense of civic duty. Chakrabarti et al. (2018) found that a sense of civic duty led some users of social media to share warnings of imminent danger regardless of their sense of the veracity (or not) of the warnings. However, in the present study, the participants who engaged in "fact addition" to make an item appropriate for sharing were practising a much more active, sophisticated, and ethical approach to civic duty.

Concern, or desire to generate awareness

Another stated motivation for sharing was general concern about the virus. For example, one Umuahia participant stated that she shared or retweeted news on COVID-19, without being concerned whether the news was fake or not, because of her concern about the virus:

I think I share some of these items because the situation worries me. The daily increase in the number of cases and deaths really makes me worried. Generally, I am interested in what is going on, so I just share. Besides, like I said before, every news basically looks the same to me, so I share whatever that is of interest to me (female businessperson, age 50, Umuahia).

For another participant, in one of the Lagos focus groups, it was acceptable to share any COVID-19 news that seemed to be somewhat accurate, and not necessarily fully accurate, because, he felt, even partially accurate information could be helpful in generating awareness of the need to take precautions:

I may share if I feel it is true to an extent. At least for people to know what is going on and know how to take care of themselves. It is better people just take precaution so if the news is about taking precaution generally, even if it is not 100%, I may consider sharing (male model, age 36, Lagos).

This quotation and the one preceding it both resonate quite directly with the findings of Chakrabarti et al. (2018) on many individuals' tendency to share danger warnings with no, or limited, concern about the veracity of the warnings.

Commercial gain

Two participants in one of the Lagos focus groups, both bloggers, said that they intentionally shared fake news when they felt it could result in commercial gain. This echoes the findings on the commercial motivation for disseminating fake news as outlined in Hirst (2017) and Marwick and Lewis (2017). Referring to the four stimulus fake news items (see Appendix) presented during the focus group discussion, one of the two participants who shared fake news, and who identified the four stimulus items as all being fake, said:

I aggressively share such stories to get readership for my blog. People will find it interesting so I share. I would share to get traffic for my blog and social media account. That's one of the things I do for a living, so I have to sustain my blogs (female entrepreneur/blogger, age 25, Lagos).

While referring to Stimulus 1, which he identified as fake news, the other Lagos participant who mentioned a commercial motivation stated as follows:

I am blogger. I focus on anything that can bring engagement. I want more, views, comments, shares, and likes. I want more subscriptions, and you know that people are attracted to things that look odd. The more engagement I have, the more money I get. People want things that are catchy and interesting (male blogger, age 25, Lagos).

Unwilling to share, due to health risks

Several participants were determined not to share fake news on COVID-19. This sentiment was reflected in these words from one of the Lagos participants who identified as a journalist:

I won't share once I feel it is fake. Anything that is not true is not likely to be of health benefit to anybody. COVID-19 is a serious health issue that we cannot afford to joke with (male journalist, age 41, Lagos).

5. Conclusions

This study explored how university-educated Nigerians in two urban centres responded to COVID-related social media fake news, and the extent to which they shared such news. Participants' sense-making practices with regard to fake news on COVID-19 were relatively varied. However, the majority of the participants shared similar impressions and perspectives on the features and spread of false information about the viral disease. Social media virality was widely viewed as synonymous with fake news, due to the dramatic, exaggerated, and sometimes illogical nature of such information, especially when placed alongside other well-known factual events. Perhaps due to their level of education, many participants demonstrated a notable level of literacy in identifying fake news. This seems to suggest that university-educated Nigerians, much like the university students in six African countries in the study conducted by Madrid-Morales et al. (2021), demonstrate some behaviours that point to their competence in dealing with false information or questionable content.

Many participants identified social media as being a natural and frequent carrier of fake news, while at the same time many also had low levels of trust in the information provided by the legacy Nigerian news media, especially government-owned platforms. This finding resonates with other studies that have found widespread distrust of the entire media ecosystem.

The motivations for sharing or not sharing fake news on COVID-19 were wide-ranging and quite nuanced. Motivations for sharing news known to be potentially fake, or at least partially fake, included a sense of concern about the pandemic and/ or a desire to create awareness of the dangers of the virus. Two respondents, both bloggers, said that they shared news that they knew was fake when they felt that the sharing would result in commercial gain. Other respondents spoke of sharing news known to be fake but adding information pointing to the fact that it was fake, so as to warn people about the dangers of fake news. It may be concluded that the individuals who felt compelled to share fake news about COVID-19 (either for commercial gain or in order to warn people of the dangers) were acting with a level of intentionality similar to that shown by people who create the fake news in the first place. Finally, some participants refused to share COVID-19 news under any circumstances. For this group of individuals, the belief that spreading false information about COVID-19 would have actual or potential negative effects on the public prevailed over any potential motivation for sharing.

The findings from this study add nuance to understanding the actions of epistemologically robust people, as examined in the research by Chua and Banerjee (2017). As detailed earlier in this article, Chua and Banerjee (2017) studied the impact of epistemic belief on sharing, or not sharing, health rumours (i.e., potential misinformation), finding that epistemologically robust people were less likely than epistemologically naïve people to share online health rumours. However, findings from the present study suggest that epistemologically robust people can display a wide range of behaviours in respect of fake news or potential fake news. For example, some of the participants who showed signs of being epistemologically robust-i.e., they understood that verifiable knowledge can be difficult to acquire-were willing to share potentially fake (or partially fake) news, because of their concern about the virus or because of a belief that sharing even unreliable information could help to make people more vigilant.

This study was not without limitations. We focused on only two Nigerian cities, on only one news topic (COVID-19), and only on participants with university degrees, which means that the sense-making and sharing behaviour with regard to fake news of a significant proportion of Nigerians was not explored. Future research into the reception of, and motivations for sharing or not sharing, fake news in Nigeria could focus on different demographics, in different locales, and on different news topics.

References

Adegoke, Y., & BBC Africa Eye. (2018). Like. Share. Kill: Nigerian police say false information on Facebook is killing people, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/nigeria_fake_news

Africa Check. (2020a). No evidence Obasanjo said there was no coronavirus in Nigeria. https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/meta-programme-fact-checks/no-evidence-obasanjo-said-there-was-no-coronavirus-nigeria

Africa Check. (2020b). No, Sultan of Sokoto didn't say Nigeria's first Covid-19 case was faked.https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/meta-programme-fact-checks/no-sultan-sokoto-didnt-say-nigerias-first-covid-19-case-was-faked

Africa Check. (2020c). No, garlic doesn't cure coronavirus. Get Covid-19 facts only from experts.https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/meta-programme-fact-checks/no-garlic-doesnt-cure-coronavirus-get-covid-19-facts-only

Africa Check. (2020d). Screenshot of Lassa fever cases, not Covid-19 numbers in Nigeria. https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/meta-programme-fact-checks/no-screenshot-lassa-fever-cases-not-covid-19-numbers-nigeria

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211-236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211 [ Links ]

Allgaier, A., & Svalastog, A. N. (2015). The communication aspects of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Western Africa - do we need to counter one, two, or many epidemics? Croatian Medical Journal, 56(5), 496-499. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2015.56.496 [ Links ]

Anderson, P. (2019, May 21). Tackling fake news: The case of Nigeria. Italian Institute for International Political Studies. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/tackling-fake-news-case-nigeria-23151

Aquino, F., Donzelli, G., De Franco, E., Privitera, G., Lopalco, P. L., & Carducci, A. (2017). The web and public confidence in MMR vaccination in Italy. Vaccine, 35(35, Pt B), 4494-4498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.029 [ Links ]

Bigman, C. A., Smith, M. A, Williamson, L. D., Planey, A. M., & Smith, S. M. (2019). Selective sharing on social media: Examining the effects of disparate racial impact frames on intentions to retransmit news stories among US college students. New Media & Society, 21(11/12), 2691-2709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819856574 [ Links ]

Brennen, B. S. (2012). Qualitative research methods for media studies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203086490

Carey, M. A. (1994). The group effect in focus groups: Planning, implementing and interpreting focus group research. In J. Morse (Ed.), Critical issues in qualitative research (pp. 225-241). SAGE.

Chakrabarti, S., Rooney, W. C., & Kweon, M. (2018). Verification, duty, credibility:Fake news and ordinary citizens in Kenya and Nigeria. BBC. https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/bbc-fake-news-research-paper-nigeria-kenya.pdf

Chadwick, A., & Vaccari, C. (2019). News sharing on UK social media: Misinformation, disinformation, and correction. Online Civic Culture Centre, Loughborough University.

Choy, M., & Chong, M. (2018). Seeing through misinformation: A framework for identifying online fake news. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1804.03508

Chua, A. Y. K., & Banerjee, S. (2017). To share or not to share: The role of epistemic belief in online health rumors. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 108, 36-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.08.010 [ Links ]

Cox, P. (2013). Fledgling website brings fact checking to South Africa. VOA News. https://www.voanews.com/a/fledgling-webiste-brings-fact-checking-to-south-africa/1725136.html

Dafonte-Gómez, A. (2018). The key elements of viral advertising: From motivation to emotion in the most shared videos. Comunicar Journal, 43. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-20 [ Links ]

Gelfert, A. (2018). Fake news: A definition. Informal Logic, 38(1), 84-117. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v38i1.5068 [ Links ]

Hirst, M. (2017). Towards a political economy of fake news. The Political Economy of Communication, 5(2), 82-94. [ Links ]

Lara-Navarra, P., Falciani, H., Sánchez-Pérez, E. A., & Ferrer-Sapena, A. (2020). Information management in healthcare and environment: Towards an automatic system for fake news detection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1066, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031066 [ Links ]

Lilleker, D. (2018). Politics in a post-truth era. International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 14(3), 277-282. [ Links ]

Madrid-Morales, D., Wasserman, H., Gondwe, G., Ndlovu, K., Sikanku, E., Tully, M., Umejei, E., & Uzuegbunam, C. (2021). Motivations for sharing misinformation: A comparative study in six Sub-Saharan African countries. International Journal of Communication, 15, 1200-1219. [ Links ]

Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/library/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/

Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2005). Africa's media, democracy, and the politics of belonging. Zed Books.

Ogwezzy-Ndisika, A. O., Amakoh, K. O., Ajibade, O., Lawal, T. O., & Faustino, B. A. (2023). Fake news and general elections in Nigeria: Fighting the canary in a digital coal mine. In U. S. Akpan (Ed.), Nigerian media industries in the era of globalization (pp. 61-72). Rowman & Littlefield.

Petersen, M. B., Osmundsen, M., & Arceneaux, K. (2023). The "need for chaos" and motivations to share hostile political rumors. American Political Science Review, FirstView, pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001447

Sandikci, O. (1998). Images of women in advertising: A critical-cultural perspective. In B. G. Englis & A. Olofsson (Eds.), E - European Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 3 (pp. 76-81). Association for Consumer Research.

Soltaninejad, K. (2020). Methanol mass poisoning outbreak: A consequence of COVID-19 pandemic and misleading messages on social media. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 11(3), 148-150. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijoem.2020.1983 [ Links ]

Tully, M. (2021). Everyday news use and misinformation in Kenya. Digital Journalism, 10(1), 109-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1912625 [ Links ]

Uwalaka, T. (2022). "Abba Kyari did not die of coronavirus": Social media and fake news during a global pandemic in Nigeria. Media International Australia, online pre-print. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X221101216

Uzuegbunam, C. E. (2020). A critical analysis of transgressive user-generated images and memes and their portrayal of dominant political discourses during Nigeria's 2015 general elections. In M. Ndlela & W. Mano (Eds.), Social media and elections in Africa, Volume 2 (pp. 223-243). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32682-1_12

Wagner, M. C., & Boczkowski, P. J. (2019). The reception of fake news: The interpretations and practices that shape the consumption of perceived misinformation. Digital Journalism, 7(3), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1653208 [ Links ]

Wang, Y., McKee, M., Torbica, A., & Stuckler, D. (2019). Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Social Science & Medicine, 240, 112552, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.10167j.socscimed.2019.112552 [ Links ]

Wardle, C. (2019). Understanding information disorder. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/understanding-information-disorder

Wasserman, H., & Madrid-Morales, D. (2019). An exploratory study of "fake news" and media trust in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. African Journalism Studies, 40(1), 107-123. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2019.1627230 [ Links ]

Welcome, M. O. (2011). The Nigerian health care system: Need for integrating adequate medical intelligence and surveillance systems. Journal of Pharmacy and Bioallied Sciences, 3(4), 470-478. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.90100 " [ Links ]

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to research assistants Janet Chijiuba, Ebube Nwigwe, and Nneamaka Daniella Okereke for their assistance with the facilitation of the focus groups.

Appendix: Focus group discussion protocol

Date..................................................

Location..................................................

Team member...............................................

Note taker.........................................................

Observer.......................................................

Duration of discussion............................................

Start..................................................................

End...................................................................

INTRODUCTIONS

First, I'd like to ask each of you to introduce yourself. A basic introduction should be enough. What is your name? Where are you from? What are you studying or doing for a living?

RECEPTION OF FAKE NEWS ON COVID-19

How do you know news on COVID-19 is fake when you see it?

How do you know news on COVID-19 is factual or true when you see it?

Which type of media is more likely to carry fake news on COVID-19?

Which type of media is more likely to carry factual news on COVID-19?

What can you say about how Nigerian media reported news on COVID-19 during COVID-19?

Which news media do you really on for news on COVID-19?

STIMULI #1-4: Motivations for sharing fake news on COVID-19

Next, I'd like you to have a look at these social media posts [show each stimulus on a large screen or mobile device].

Questions (for each stimulus)

What would be your first reaction if you saw this on your Twitter or Facebook timeline?

Has anybody you know, maybe a friend or a relative, ever shared with you content similar to this? What did you do?

Would you consider sharing this post? Why or why not?

Prompts for additional reasons [use if these reasons haven't been mentioned]

Do you feel that putting this up on Facebook or Twitter would get you more likes or retweets? Why do you think this would be the case? [motivation: social currency / social media recognition]

Would you share these to make people aware of possible dangers? Even if you thought it wasn't true? [motivation: civic duty]

Does anybody here feel that they have a moral obligation or that it is their right to share this kind of information? [motivation: obligation, right]

How many of you would check with a more established news source before sharing? How often do you do this?

Do your friends or relatives share news on coronavirus? Do you ask them not to do it? Can you recall sharing a story on COVID-19 that you later found out was not fully accurate?

Why did you share it?

Did something happen after you shared it? For example, did you eventually take it down or did you leave it? Why did you take it down / why did you leave it? Did someone correct you, or ask you to take it down?

Has anyone deliberately shared news that you knew was completely made up? If yes, why did you share it?

OPTIONAL

How much of a problem do you think misinformation and fake news on COVID-19 are? What do you usually do when somebody shares news on COVID-19 that you know is made up? What is your reaction?

How often do you use fact-checking websites? Do you know any that are reliable?

WRAP-UP

[This last section is meant to provide a quick summary of the discussion, to make sure participants agree with the key takeaways identified by the discussion leader. These questions should help people raise additional points they were unable to make during the discussion.]

Possible questions:

Today you have covered the following topics [provide a 3-to-5-point summary of the discussion] Do you feel this is an adequate summary?

Have we missed anything? Would you like to add one last thing?

Thank you all for your time. As explained before we started, today's discussion was aimed at gathering qualitative data for a study which explores the reception, and motivations for sharing, fake news on COVID-19. If somebody wants to know about the findings, please let me know and we'll be happy to share them with you.

With this we have come to the end of this focus group discussion. Thank you all for participating.