Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The African Journal of Information and Communication

On-line version ISSN 2077-7213

Print version ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.30 Johannesburg 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/ajic.i30.13910

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Roles played by Nigerian YouTube micro-celebrities during the COVID-19 pandemic

Aje-Ori Agbese

Associate Professor, Department of Communication, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Edinburg, Texas; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4783-9113

ABSTRACT

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Nigerian social media micro-celebrities were prominent players in the dissemination of information. This study examines the roles that one group of Nigerian micro-celebrities, YouTube video bloggers (vloggers)-also known as "YouTubers"-played during the pandemic. The research analysed the contents of COVID-19-themed videos that 15 popular Nigerian YouTubers posted on their channels between 29 February and 5 August 2020. The study was guided by the two-step flow of communication theory, in terms of which information first flows from mass media to opinion leaders, who then, in the second step, share the information with their audiences. The study found that all 15 YouTubers played positive roles as opinion leaders-by providing health and safety information on COVID-19, challenging myths, and educating audiences through entertainment. Only two of the YouTubers studied were found to have shared some information that misinformed their audiences about the virus and how to fight it. The study therefore concluded that Nigerian YouTubers, as opinion leaders, can be important allies to governments and organisations when health crises arise in the country.

Keywords: COVID-19, communication, social media, micro-celebrities, YouTubers, opinion leaders, two-step flow of communication theory, Nigeria

1. Introduction

In times of crisis, social media channels are often the "initial source of information" when news breaks (Wohn & Bowe, 2016, p. 1). For example, when the Zika and Ebola pandemics started, YouTube saw a "tremendous surge in viewer traffic" (Bora et al., 2018, p. 321). Those who rush to social media in times of crisis do so believing that the information posted there is valid and trustworthy (Cuomo et al., 2020). This high level of trust that most social media users have in the information they receive through these channels makes it necessary to explore the roles that influential social media, led by their most prominent users, can have during a pandemic.

Such exploration is acutely necessary because social media spread large quantities of both false and true information (Tangwa & Munung, 2020). Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that false information spreads "significantly farther, faster, deeper and more broadly than truth" on social media (Vosoughi et al., 2018, p. 2). It has been found, for instance, that during the Zika epidemic from 2015 to 2016, misleading posts on Facebook were more popular than accurate ones (Bora et al., 2018). Within weeks of the outbreak of COVID-19, fearmongering, misinformation, and conspiracy theories regarding the virus were rife on social media (Depoux et al., 2020). Accordingly, social media can escalate public fear and undermine public health efforts because they have enormous influence on their audiences' actions, beliefs, and interests (Mookadam et al., 2019). Therefore, social media's influence during the COVID-19 pandemic requires close examination, especially because lockdowns increased the amount of time that people spent on social media.

A prominent element of social media's influence is its micro-celebrities- users who have achieved celebrity status through social media (Senft, 2008; Kostygina et al., 2020). Unlike traditional celebrities who achieve their fame through traditional media (e.g., movies, music, or television), micro-celebrities' fame comes from self-produced content and providing direct and frequent intimate access to their lives (Seo & Hyun, 2018). They reach many people quickly because followers are instantly notified about new posts. The more followers that a micro-celebrity has, the greater their influence (Chung & Cho, 2017).

For example, research has determined that popular micro-celebrities have considerable influence on their followers' choices and decisions (Abidin, 2015). Kirkpatrick et al. (2018) found that micro-celebrities' product recommendations yielded 11 times more profit than other forms of advertising. Schouten et al. (2020) found that people trusted micro-celebrities more than traditional celebrities when choosing celebrity-endorsed products. Therefore, companies regularly use micro-celebrities in their marketing. Popular micro-celebrities also receive sponsorships and are paid for product endorsements or using products on their channels. However, there is a paucity of research on micro-celebrities' roles beyond advertising and marketing (Kostygina et al., 2020).

Accordingly, this study examined the roles played by micro-celebrities in a health context. Specifically, the research examined the roles that popular Nigerian YouTube video bloggers (vloggers)-also known as "YouTubers"-played during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country, between 29 February and 5 August 2020. The study focused on YouTubers because YouTube is "an important vehicle for sharing and disseminating timely health-related information, both in its function as a repository of videos and as a social networking interface where users can interact and socialize" (Madathill et al., 2015, p. 174). When COVID-19 caused global lockdowns, millions of people turned to YouTube to satisfy their need for quarantine information, self-care information, and entertainment (YouTube, 2020a). YouTube is also an important source because popular YouTubers develop relationships with their viewers and influence them (Senft, 2008).

Another reason for this study's focus on Nigerian YouTubers is the prominence of Nigeria's celebrity culture. In 2019, it was estimated that 62% of Nigerians were online and highly active on social media; that about 53% of Nigerian internet users visited YouTube daily; and that many were content creators (Udodiong, 2019). Some Nigerian YouTubers, such as Mark Angel, Dimma Umeh, and Taaooma Akpaogi, were found to have become celebrities and achieved global fame (Oludimu, 2019).

The research analysed the contents of 56 COVID-19-themed videos posted by 15 popular Nigerian YouTubers. The analysis of the findings was guided by the two-step flow of communication theory, in terms of which information first flows from mass media to opinion leaders, and then, in the second step, from the opinion leaders to their audiences.

2. Literature review

Understanding micro-celebrity on YouTube

The YouTube video-sharing platform, launched in 2005, is currently used by approximately 2.5 billion people worldwide (Kemp, 2022). Its popularity lies in "its user-generated content, which includes tutorials, reviews, reactions, pranks, confessionals, and much more" (Miller, 2017, p. 3). YouTubers, described by Jerslev (2016, p.5233) as "video bloggers (vloggers) who regularly post videos on their personal YouTube channels", speak directly to audiences on niche subjects through the camera, and broadcast from private environments such as kitchens, living rooms, and bedrooms.

According to Jerslev (2016, p. 5238), being a YouTuber requires "continuous and multiple uploads of performances of a private self" and the use of "access, immediacy, and instantaneity" to build intimacy. This means that, unlike traditional celebrities who guard their privacy and separate their private and public lives, YouTubers blur that boundary and give audiences constant access to their private lives (Marwick, 2015). In addition, while glamour and extraordinariness characterise traditional celebrities, ordinariness, closeness, and equality characterise YouTubers. YouTubers must also quickly respond to comments, sometimes in a video, to maintain a positive relationship with their followers (Song, 2018).

In this micro-celebrity world, the number of likes, comments, shares, and subscribers that a YouTuber gains determines their success. Consequently, successful YouTubers can become influential figures whom people consult for information, entertainment, and recommendations (Abidin, 2015). For example, Sobande (2017) found that Black women in Britain relied on popular natural hair YouTubers for hair tips and product recommendations. Coates et al. (2020) found that children who watched their favorite YouTubers eating unhealthy snacks increasingly ate unhealthy snacks.

Research suggests that a YouTuber's credibility is tied to their perceived authenticity and closeness (Jerslev, 2016). Authenticity can be tied to a perception that a YouTuber is real and free from corporate control (Salyer & Weiss, 2020). According to Baker and Rojek (2019), authenticity is a valuable tool on YouTube because the platform's identity as an uncommercialised do-it-yourself space where ordinary people can freely express themselves requires genuineness. Therefore, audiences expect authenticity and honesty from YouTubers.

YouTubers can express authenticity in several ways. These include saying and showing that they are accessible, spontaneous, ordinary, and always themselves. They can also document real issues, share intimate information, and suggest that they and their audiences are alike (Jerslev, 2016). Furthermore, YouTubers can build authenticity through intimate conversations. Salyer and Weiss (2019) and Tolbert and Drogos (2019) found that people regarded their favourite YouTubers as friends when the YouTubers were perceived as authentic. And it was found that such YouTubers were particularly influential among their subscribers.

However, Marwick and boyd (2011, p. 124) point out that authenticity does not have a universal definition because what people regard as authentic depends on "the person doing the judging". Therefore, a YouTuber must find a balance between "personal authenticity and audience expectations" in order to appeal to, gain, and maintain subscribers (Marwick & boyd, 2011, p. 127). YouTubers can quickly lose followers when they are seen as inauthentic for any reason (Baker & Rojek, 2019).

Another important trait of successful YouTubers is closeness. According to Salyer and Weiss (2020), closeness means audiences feel connected to a YouTuber. Similar to how they build authenticity, YouTubers can create an "impression of connectedness" by providing continuous updates on their lives, being relatable, and seeking input from their viewers (Jerslev, 2016, p. 5241). Lifestyle YouTubers, for example, build closeness "by presenting themselves as friends and equals" (Baker & Rojek, 2019, p. 4).

A disadvantage of closeness, however, is that it can create "parasocial" relationships- in which audience members feel a false sense of connection or intimacy with the YouTuber-that make the audience members highly susceptible to doing what a YouTuber asks (Tolbert & Drogos, 2019). Social media "are especially potent in establishing parasocial relationships of trust and intimacy" because they are structured and presented as "a direct exchange between equals" (Baker & Rojek, 2019, p. 9). Niu et al. (2021) found that this parasocial structure was particularly strong for YouTube audiences during COVID-19 lockdowns because YouTubers met people's need for human connection.

In addition to authenticity and closeness, research suggests YouTubers are influential when they are perceived as relatable (in appearance and in the information that they provide), inspiring, sincere, attractive, informal, experienced yet ordinary (imperfect), and sharing similar demographic characteristics with subscribers (Djafarova & Trofimenko, 2019; Smith, 2017). YouTube audiences' choices of whom to watch or follow are also contextual, because people choose channels based on what they need at a particular moment (Marwick & boyd, 2011).

Popular YouTubers' extensive reach and influence make them potentially important sources of leadership roles in certain situations (Senft, 2008). For example, rates of loneliness and depression increased in the United States during COVID-19-related lockdowns (Rosenberg et al., 2021). Consequently, US YouTubers participated in social media's #StayHome #WithMe (SHWM) movement, helping people to cope and connect with others by posting entertaining and comforting content that reduced people's stress and diverted their attention from pandemic-related stressors (Niu et al., 2021). Sofian (2020) found that five popular Indonesian YouTubers raised public awareness about COVID-19 to counter false information when the Indonesian government did not.

Theoretical framework

This study applied Katz and Lazarsfeld's (1955) theory of a two-step flow of communication to the contemporary social media context. This theory holds that information first flows from the media to opinion leaders and then, in the second step, to a less involved public. Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955) argued that opinion leaders were casual but influential acquaintances, friends, and family who could shape their peers' attitudes and behaviours through interpersonal, face-to-face communication. They were also well-connected, strongly exposed to media, and associated with bringing new innovations to the community. For Hameed and Sawicka (2017), opinion leaders are people "who have a greater-than-average share of influence within their community" (2017, p. 36).

However, Bennett and Manheim (2006, p. 215) challenge the relevance of Katz and Lazarsfeld's conception of communication flow in the contemporary context, arguing that "the combination of social isolation, communication channel fragmentation, and message targeting technologies have produced a very different information recipient" from the 1950s. They argue that people are now less likely to congregate in groups to receive information, and that social media have made face-to-face communication less prevalent, creating a one-step flow of information (without opinion leaders).

However, many authors still see the relevance of two-step conceptions. Starbird and Palen (2012) argue that rather than removing opinion leaders, social media have provided new opportunities for opinion leaders to exert their influence-thus maintaining the existence of a two-step flow of information. Winter and Neubaum (2016) point to the power of social media in the hands of opinion leaders, stating that such media provide "an ideal venue for influencing others" (2016, p. 2). Schafer and Taddicken's (2015) study on German internet users identifies pockets of opinion leaders and a framework resembling Katz and Lazarsfeld's conception of two-step communication flow.

Bergstrom and Jervelycke Belfrage (2018) found that opinion leaders on social media are those who bring attention to, and add context to, certain news items, and thus people perceive them as crucial news providers. Hansen et al. (2011, p. 23) find that bloggers are influential opinion leaders because they can "build audiences that rival pre-digital media and challenge more established information providers." Turcotte et al. (2015) find that people increasingly trust news outlets that opinion leaders endorse on social media. News-sharing, whereby people share "information that is already available elsewhere" and make it "personally relevant to their social network", also suggests a two-step flow of communication (Oeldorf-Hirsch & Sundar, 2015, p. 241). In another study, Velasquez (2012) discovers that expertise cues from popular social media figures generate the greatest feedback in only public discussions. Zimmermann et al. (2020) find that YouTubers who cite sources gain greater perceived credibility.

At the same time, there is evidence that opinion leaders on social media can "amplify the effects of disinformation" when they do not verify information or simply echo what others have said (Dubois et al., 2020, p. 8). In the Nigerian context, social media influencers have been found to share conspiracy theories and misinformation to grow audiences (Hassan, 2020).

This study was grounded in the assumption that conceptions of a two-step flow of communication are still relevant today, and focused on the following research questions:

• What types of content did Nigerian YouTubers create and share concerning COVID-19 during the pandemic?

• What role(s) did Nigerian YouTubers play during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria?

• To what extent did Nigerian YouTubers provide false or misleading information on COVID-19?

3. Research design

To find Nigerian YouTubers' videos on COVID-19, a search for "Nigerian YouTubers" (key term) was conducted on YouTube. This produced 1,020 people, whose number of subscribers ranged from just seven to over 6 million.

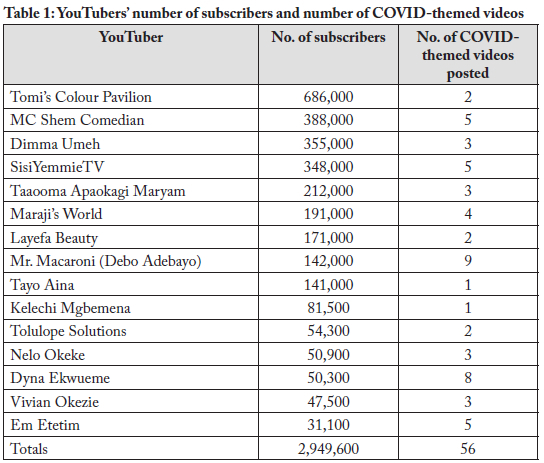

To be included in the study, a YouTuber had to: be a Nigerian in Nigeria (YouTubers indicate their nationality and locations in their profiles); be an individual (not a duo or group); have at least 30,000 subscribers; and have posted content on COVID-19. These criteria produced 15 people. Combined, the 15 YouTubers selected for the study had, as of 7 August 2020, more than 2.9 million subscribers and over 360 million views (see Table 1).

These 15 individuals' YouTube channels were then searched for videos they had posted on COVID-19 between 29 February 2020 (when Nigeria's first COVID-19 case was announced) and 5 August 2020. Altogether, 56 COVID-19-themed videos were found (see Table 1). The least viewed of these videos had, as of 7 August 2020, been watched 2,775 times, and the most viewed had been watched 1.2 million times.

Following the identification of COVID-19 videos, each video was reviewed twice and evaluated qualitatively, with a focus on the roles being played by the YouTubers.

4. Findings

The YouTubers'characteristics and styles

The 15 YouTubers all lived in three large Nigerian cities: 12 in Lagos, two in Port Harcourt, and one in Abuja. The YouTubers comprised three males (MC Shem, Tayo Aina, and Mr. Macaroni) and 12 females. In terms of content, four of the channels- those of two of the males (MC Shem and Mr. Macaroni) and two of the females (Maraji and Taaooma)-consisted primarily of comedy. Male YouTuber Tayo Aina's channel focused on travel and real estate; female YouTuber Tomi focused on lifestyle and natural health remedies, and female YouTuber SisiYemmie's channel focused on food and lifestyle. The other five channels, all run by females, were focused on lifestyle and beauty.

It was found that the YouTubers employed several authenticity and closeness techniques to build intimacy, including (in the case of the females) showing their faces without makeup, speaking directly to viewers as if they were friends and family, including family and friends in videos, and sharing private information.

The YouTubers also built intimacy through their locations, shooting their videos in personal spaces such as cars, bedrooms, kitchens, and living rooms. In several cases, the YouTubers recorded themselves while they engaged in an activity, such as running an errand, attending a party, visiting a hair salon, or speaking to friends.

The female YouTubers were found to be more likely than the males to use closeness techniques to connect with their audiences, including intimate conversations and using emotions to build closeness; crying when discussing personal problems in their relationships or health; frequent updates for viewers; and encouragement of feedback. One YouTuber, Ekwueme, identified her subscribers as "Dynamites" as a means to build closeness.

Four YouTubers (males MC Shem and Mr. Macaroni, and females Maraji and Taaooma) played fictional characters as part of their aforementioned emphasis on comedy. These characters also tended to use memorable catchphrases to build familiarity (Mr. Macaroni's "you are doing well", for example). MC Shem and Mr. Macaroni never switched out of their fictitious characters, while Maraji and Taaoma did, infrequently, post videos on their personal lives.

The YouTubers'roles

The qualitative analysis of the roles played by the 15 YouTubers across the 56 videos identified three main themes: (1) YouTubers as information providers, (2) YouTubers as myth-busters, and (3) YouTubers as entertainers.

YouTubers as information providers

The YouTubers informed audiences on coronavirus and its impact. The lifestyle YouTubers acted like reporters and provided perspective on what was happening. In a variety of ways, they shared news and discussed the lockdowns, coping strategies, stocking up on necessities, hygiene, masks, and COVID-19 symptoms. One way was through promotions, which they used to introduce new innovations to Nigerians. For example, while giving viewers coping tips in the "spirit of quarantine", Ekwueme (2020a) promoted Naija Lyfe, an entertainment app, and encouraged people to use it while staying at home. Macaroni, during his live shows, promoted VBank, a digital banking service for receiving or sending money-because people could not go to the bank.

The YouTubers also participated in news sharing. Five YouTubers shared information from CNN, Al Jazeera, the Los Angeles Times, Ghanaian YouTuber Wode Maya, and Twitter. Umeh's (2020) 19 April video entitled "Can we talk about this???!!!" used news screenshots from CNN, Al Jazeera, and the Los Angeles Times to highlight and contextualise the maltreatment of Black Africans in China because of the coronavirus. She discussed how upset she was that the pandemic had taken a racist turn that blamed Africans in China for COVID-19. She wanted more people talking about it because "It makes no sense. It hurts too much, and just makes you question so many things" (Umeh, 2020). CNN also played in the background in four people's videos, and Shem incorporated CNN in three skits. Interestingly, only Ekwueme cited a local media source, Instablog Naija. However, she did this to counter some information the site provided on Rivers State's lockdown (she lives there). This suggests she used her position as a YouTuber to challenge media discourse by sharing her arguments and position. Health sources also appeared in the videos, including a medical doctor in Macaroni's #Luckdownmillionaire, the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), UNICEF, and the World Health Organisation.

Another way in which the YouTubers shared information was by documenting what they were doing. The lifestyle YouTubers, in particular, showed themselves social distancing, wearing masks, and using hand sanitiser when they went out. They described how unusual it was to see their typically busy cities looking quiet and empty. Several YouTubers also highlighted some challenges that the pandemic and lockdown created in Nigeria. These challenges included loneliness, people not wearing masks or social distancing because of conspiracy theories, panic buying, and robberies. In a video entitled "Lagos lockdown/A day in my life/Social distancing???", SisiYemmie painted a dire picture of Lagos and its lockdown's effect on people's access to food. She called Lagos' lockdown "pointless" because people moved freely from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. but were required to stay home from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. (SisiYemmieTV, 2020). She questioned the logic in letting people go out at all. "Are we going to say, Coro, wherever you dey [are], behave yourself, to avoid catching the virus?" she asked (SisiYemmieTV, 2020).

Etetim also shared the difficulty that organisations faced in enforcing social distancing rules. In a video entitled "What life under quarantine in Nigeria really looked like", posted on 26 June, she showed a bank where people crowded the doors without masks and were not social distancing (Etetim, 2020). Although she showed a place where people followed health guidelines, she said that, overall, Nigerians were not taking coronavirus seriously "because the number of deaths isn't so alarming" (Etetim, 2020). She concluded: "Nigeria is not really a place where people are very open to being careful or listening to what people are saying" (Etetim, 2020).

In an 18-minute self-described "rant" entitled "Nigerians are wicked", Ekwueme (2020b) also discussed several coronavirus-related issues. She talked about Nigerians exploiting the pandemic in Rivers State. For example, although the State Governor announced a lockdown starting at 6 p.m. on 26 March, police closed the state's borders early, before 10 a.m., and started charging people 1,000 to 2,000 Naira (approx. USD2.5 to USD5) to enter the state. She also pointed to the fact that the cost of food and essential commodities had soared, stating that the cost of vegetables rose sharply on 26 March, resulting in panic buying and hoarding.

Ekwueme then talked about the challenge of staying home without the kind of support that people in the United States, Canada, and several other countries received from their governments. Requiring Nigerians to stay at home daily without food or financial aid was especially difficult for those who relied on daily incomes and had no savings. Ekwueme (2020b) said: "As citizens, we are entitled to salaries every month at least until this thing is done and dusted." She said that hunger would otherwise undermine the lockdown's purpose because unless people had money and food at home while isolating, they would go out "to fend for themselves. Lockdown won't happen in Nigeria. It will never happen if you're not providing the essentials for the people" (Ekwueme, 2020b). She added that, unlike other leaders who addressed their citizens about the pandemic at least once a day, Nigeria's President Muhammadu Buhari was "nowhere to be found", because he had not addressed the country. She described the government as "paralyzed", with "no clue whatsoever" on the pandemic (Ekwueme, 2020b). Coincidental^, Buhari addressed Nigeria on 29 March 2020. Ekwueme's rant video generated 618 comments, with many supporting her opinions and observations.

In a video skit entitled "My mother has corona virus (COVID-19)", Shem highlighted how Nigerians were maltreating and shunning those with coronavirus-like symptoms, such as sneezing and coughing, without proof of a positive test. Ekwueme (2020b) said the fear of discrimination probably dissuaded people from getting tested when they had COVID-like symptoms, and this would negatively affect the government's efforts.

The YouTubers also discussed personal issues related to the pandemic and how they were coping. They said that they had learned new skills, decluttered closets, bonded with family, exercised, and cooked. Aina said that he found it difficult to create, and felt unmotivated and lonely. Etetim shared these sentiments. She said that she first viewed the lockdown as "a mini-vacay. A break the world needed" that would last a week (Etetim, 2020). Aside from highlighting challenges, two YouTubers provided information to help people too. For those who did not want to go shopping, Umeh and Okeke shared WhatsApp numbers that people in Lagos and Port Harcourt could use for home-delivered groceries or curbside shopping at grocery stores, which were innovations in Nigeria too.

However, the only prevention and safety behaviours that the YouTubers emphasised were using hand sanitiser, wearing masks, no touching or hugging, isolating, and taking vitamin C. Fourteen YouTubers did not address covering your face when you sneezed or coughed, cleaning and disinfecting surfaces, and how long people should wash their hands for with soap. Overall, the videos under this theme confirmed Bergstrõm and Jervelycke Belfrage's (2018) finding that social media leaders can bring attention to news that others missed and can also add context.

YouTubers as myth-busters

The second observed role involved busting COVID-19 myths. The YouTubers tackled several myths, including the myths that spreading onions around the house would kill the virus; that COVID-19 was like Ebola and would be eradicated quickly; that Uber Eats, TikTok, and Disney+ created COVID-19; and that Christians and people who ate starchy foods could not contract the virus. They countered the myths with facts and satire. To prove that Black people could get COVID-19 because the first case in Nigeria was an Italian man, Tomi showed Idris Elba's announcement of his positive COVID-19 test. Ekwueme also addressed the myth that COVID-19 only affected wealthy people. She said the myth was common because test kits were not widely available and only prominent people's deaths were announced on the news and social media. As a medical doctor's wife, she emphasised that anyone could get it. Surprisingly, none of the YouTubers addressed the popular Nigerian conspiracy that blamed mobile 5G networks for COVID-19 (Adebayo, 2020; Wonodi et al, 2022).

YouTubers as entertainers

Finally, the YouTubers provided entertainment through comedy skits. Here, the YouTubers showed Nigerians' ability to find a "comic dimension" in any issue (Afolayan, 2013, p.164). As Nigerians also view social media as a "laughing space" where they can still highlight societal issues, it was not surprising that these videos were the most viewed (123,237 to 1.2 million) (Yékú, 2016, p. 249). These numbers matched Niu et al.'s (2021) finding that people turned to YouTube for entertainment and distraction during the pandemic. Johnston's (2017) finding that comedy can increase viewership and engagement is also supported. The lifestyle YouTubers also employed comedic strategies such as blundering to make their videos fun. A popular strategy that the comedy YouTubers used was satire, which refers to using humour, ridicule, or exaggeration to expose and criticise people's depravities.

For example, Taaooma depicted a coronavirus-fighting soldier in a music video she posted on 18 April that probed Nigerians' resistance to compliance unless the government used force. In another skit, Macaroni (2020) satirically presented loneliness, robbery, fraud, and hunger as the "many children of coronavirus" in Nigeria because the government did not provide palliatives or prepare Nigerians. He also called COVID-19 the "hunger virus" (Macaroni, 2020). These were jabs at the economic and security problems that the pandemic created or heightened in Nigeria.

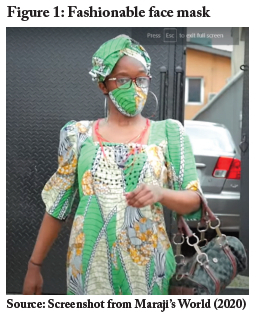

In two videos, Maraji also used satire. In a 28 March video, she satirically exposed the types of people (conspiracy theorists, newscasters, panicky, calm, indifferent, serious, and church lawbreakers) that the pandemic created. For example, the conspiracy theorists believed the virus was "planned work" and an "economic strategy" to raise prices and make money (Maraji's World, 2020). The church lawbreakers violated lockdown regulations and went to church because "coronavirus cannot hold us down. We are children of God. What will affect others cannot affect us" (Maraji's World, 2020). Her second video, entitled "Wearing masks in a pandemic", highlighted Nigerians' adaptability. The video started with frightening music and images of Chinese people wearing masks, and then switched to an upbeat Nigerian song that played in a fashion show where Maraji showed how Nigerians had made masks a fashion statement. Maraji sashayed out of the house in different clothes, for men and women of different ages, with matching face masks (Figure 1).

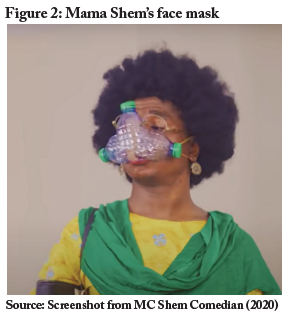

Shem also ridiculed the things that people used for masks in a skit entitled "Face mask". In it, his mother made a face mask using plastic bottles (Figure 2). The skit exposed and poked fun at Nigerians who used anything, including soap dishes, for face masks, an issue that memes also highlighted, and addressed the lack of information on correct face masks in Nigeria (Dynel, 2020).

False or misleading information

To control misinformation, YouTube started using an automated system on 16 March 2020 to flag and remove misleading COVD-19 content (YouTube, 2020b). However, the system also removed safe COVID-19 videos and caused self-censorship on YouTube. To avoid getting flagged or removed, four of the YouTubers studied said that they could not say the word "coronavirus" and instead used the words "virus", "corona", or other nicknames such as "Coro", "rona", and "rororo". Three of the YouTubers spelt "coronavirus" as "corona virus" in video titles. But this self-censorship did not stop two YouTubers from sharing misleading information.

Tomi's vlog on 19 March 2020, entitled "Is This a Cure for Corona Virus? Find Out" promoted a COVID-19 cure. She shared a hairdryer method that she said cured COVID-19 patients in a London hospital. The method involved putting a hairdryer on cool and blowing air around the face. She cited "reliable sources in London" and said the hairdryer method "has been helping a few patients get out of this" (Tomi's Colour, 2020). She said that she could not reveal the hospital or her sources for safety reasons and asked viewers to trust that the information was credible. However, the information that Tomi provided on the hairdryer method echoed a viral video that Facebook and YouTube removed in March 2020 for being false (Dunlop, 2020).

Ekwueme (2020b) also shared unsubstantiated information. She said poor Nigerians were "denied testing" and test kits were not available to the poor in Nigeria (Ekwueme, 2020b). However, she provided no sources to support the information. Ekwueme and Tomi's comments confirmed Dubois et al.'s (2020) finding that micro-celebrities can strengthen disinformation when they simply echo sentiments or do not verify information.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Guided by the two-step flow of communication theory, this study sought to examine the roles that 15 Nigerian YouTubers played during the COVID-19 pandemic and to fill the gap on Nigerian micro-celebrity research. The findings revealed that Nigerian YouTubers can be important sources of information. During the pandemic, they provided information, raised awareness, entertained, challenged myths, and acted as opinion leaders online. These YouTubers also participated in the #stayathome movement that encouraged people to remain indoors during lockdown.

This suggests that YouTubers played positive roles during the pandemic through social media. Several of this study's findings also matched previous studies on YouTubers. Like Western YouTubers, Nigerian YouTubers, particularly women, use authenticity and closeness to engage and interact with audiences (Miller, 2017; Salyer & Weiss, 2019). However, contrary to Jerslev's (2016) definition of a YouTuber as a vlogger, the data characterised Nigerian YouTubers as more than vloggers. A Nigerian YouTuber is more likely to be a content creator who can also attract an audience through fictional characters.

According to Marwick (2015), micro-celebrities sometimes adopt fake identities to hide their real identities in order to address the impossibility of maintaining a single identity and/or to target different audiences. This may explain why Nigerian YouTubers play fictional characters and combine content types. Therefore, anyone studying YouTubers must define them in ways that capture the unique characteristics and conditions that match their context.

This study also confirmed previous findings that opinion leaders exist in newer media (Choi, 2014). As opinion leaders, the 15 YouTubers understood that people would look to them for information, perspective, and entertainment during the lockdown. Therefore, they created content to meet those needs. They also interpreted and channelled information from news sources to their audiences through vlogs, comedic skits and more, opined on social issues, offered corrections without lecturing through comedy, shared innovations, and encouraged viewers to share their experiences and thoughts in the comments section. This supported Niu et al.'s (2021) finding that YouTubers helped people to cope and illustrated how YouTubers can lead public discussions on relevant issues in Nigeria (Grzywinska & Borden, 2012). The feedback that they generated from users could produce invaluable public perspective on social issues in Nigeria. As news sharers, they confirmed that news flows from the media to opinion leaders, who then share it with their followers (Oeldorf-Hirsch & Sundar, 2015).

However, two individuals shared false information, which confirmed Wonodi et al.'s (2022) finding that Nigerian social media was rife with falsehoods on COVID-19. Tomi's cure video was particularly risky because her channel, which had the most subscribers among the 15 YouTubers studied, shares natural health do-it-yourself remedies, which many Nigerians prefer over pharmaceuticals (Alabi et al., 2021). During the pandemic, 60% of Nigerians said that herbal medicine could successfully treat COVID-19, and 80% believed that they could not contract COVID-19 because they used herbal medicine diligently (Alabi et al., 2021).

Therefore, when YouTubers mislead their audiences they can negatively impact the medical advice and choices that people receive or make (Olapegba et al., 2020). When YouTubers do not verify information or rush to share what they find, they can become echo chambers for fake sources and can put people's lives at risk. Consequently, YouTubers must research and confirm the information and sources that they receive before sharing it.

Overall, despite using a small sample, the study found important information on Nigerian YouTubers. If another health crisis occurs in Nigeria, the Nigerian government and health organisations will benefit from including micro-celebrities in health campaigns to reach and educate people. Future studies could examine Nigerian YouTubers' influence from the audience's perspective. Studies could also include analysis of the content of the YouTube comments section, so as to better gauge audience engagement with the videos and messages.

References

Abidin, C. (2015). Communicative intimacies: Influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada: Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, 8, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.7264/N3MW2FFG [ Links ]

Adebayo, B. (2020, May 19). UK regulator sanctions Nigerian Christian channel over 5G conspiracy theory claims. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/19/africa/ofcorn-sanctions-5g-conspiracy-theory-intl/index.html

Afolayan, A. (2013). Hilarity and the Nigerian condition. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 6(5), 156-174. [ Links ]

Alabi, G.O., Dada, S. O., Adebodun, S. A., & Obi, O.C. (2021). Knowledge of COVID-19 and perception of Nigerians towards the use of herbal medicine in its treatment. Nigerian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 17(2), 157-166. https://doi.org/10.4314/njpr.v17i2.2 [ Links ]

Alexander, J. (2020, March 4). YouTube is demonetizing videos about coronavirus, and creators are mad. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/4/21164553/youtube-coronavirus-demonetization-sensitive-subjects-advertising-guidelines-revenue

Baker, S. A., & Rojek, C. (2019). The Belle Gibson scandal: The rise of lifestyle gurus as micro-celebrities in low-trust societies. Journal of Sociology, 56(3), 388-404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319846188 [ Links ]

Bennett, W. L., & Manheim, J. B. (2006). The one-step flow of communication. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 608(1), 213-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206292266 [ Links ]

Bergstrom, A. & Jervelycke Belfrage, M. (2018). News in social media: Incidental consumption and the role of opinion leaders. Digital Journalism, 6(5), 583-598. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1423625 [ Links ]

Bora, K., Das, D., Barman, B., & Borah, P. (2018). Are internet videos useful sources of information during global public health emergencies? A case study of YouTube videos during the 2015-16 Zika virus pandemic. Pathogens and Global Health, 112(6), 320-328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604 [ Links ]

Choi, S. (2014). The two-step flow of communication in Twitter-based public forums. Social Science Computer Review, 33(6), 696-711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314556599 [ Links ]

Chung, S., & Cho, H. (2017). Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychology & Marketing, 34(4), 481495. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21001 [ Links ]

Coates, A. E., Hardman, C. A., Halford, J. C. G., Christiansen, P., & Boyland, E. J. (2020). "It's just addictive people that make addictive videos": Children's understanding of and attitudes towards influencer marketing of food and beverages by YouTube video bloggers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 449, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020449 [ Links ]

Cuomo, M. T., Tortora, D., Giodano, A., Festa, G., Metallo. G., & Martinelli, E. (2020). User-generated content in the era of digital well-being: A netnographic analysis in a healthcare marketing context. Psychology & Marketing, 37, 578-587. [ Links ]

Depoux, A., Martin, S., Karafillakis, E., Preet, R., Wilder-Smith, A., & Larson, H. (2020). The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(3), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa031 [ Links ]

Djafarova, E., & Trofimenko, O. (2019). Instafamous - credibility and self-presentation of micro-celebrities on social media. Information, Communication & Society, 22(10), 1432-1446. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1438491 [ Links ]

Dubois, E., Minaeian, S., Paquet-Labelle, A., & Beaudry, S. (2020). Who to trust on social media: How opinion leaders and seekers avoid disinformation and echo chambers. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120913993 [ Links ]

Dunlop. W. G. (2020, March 19). Hot air from saunas, hair dryers won't prevent or treat COVID-19. AFP Fact Check. https://factcheck.afp.com/hot-air-saunas-hair-dryers-wont-prevent-or-treat-covid-19.

Dynel,M.(2020).COVID-19 memes going viral:On the multiple multimodal voices behind face masks. Discourse & Society, 32(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926520970385 [ Links ]

Ekwueme, D. (2020a, April 5). Self-isolating in my lonely marriage. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6WiElLEJHs

Ekwueme, D. (2020b, March 29). Nigerians are wicked. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BebgbpMV10I

Etetim, E. (2020, June 26). What life under quarantine in Nigeria really looked like. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2Hx70ZzQT4

Grzywinska, I., & Borden, J. (2012). The impact of social media on traditional media agenda setting theory: The case study of Occupy Wall Street movement in USA.

In B. Dobek-Ostrowska, B. Lodzki, & W. Wanta (Eds.), Agenda setting old and new problems in the old and new media (pp. 133-155). University of Wroclaw Press.

Hameed, T., & Sawicka, B. (2017). The importance of opinion leaders in agricultural extension. World Scientific News, 76, 35-41. [ Links ]

Hansen, D. L., Smith, M. A., & Schneiderman, B. (2011). Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: Insights from a connected world. Morgan Kaufmann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-382229-1.00002-3

Hassan, I. (2020, March 27). COVID-19: The dual threat of a virus and a fake news epidemic. Premium Times. https://opinion.premiumtimesng.com/2020/03/27/covid-19-the-dual-threat-of-a-virus-and-a-fake-news-epidemic-by-idayat-hassan/?utmsource=headtopics&utm_medium=news&utm_campaign=2020-03-27

Jerslev, A. (2016). In the time of the microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. F., Worth, A., & Brookover, D. (2019). Families facing the opioid crisis: Content and frame analysis of YouTube videos. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 27(2), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480719832507 [ Links ]

Johnston, J. (2017). Subscribing to sex edutainment: Sex education, online video and YouTube star. Television and New Media, 18(1), 76-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476416644977 [ Links ]

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Free Press.

Kemp, S. (2022, August 15). YouTube statistics and trends. Datareportal. https://datareportal.com/essential-youtube-stats

Keyton, J. (2011). Communication research: Asking questions, finding answers (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Kirkpatrick, N., Pederson J., & White, D. (2018). Sport business and marketing collaboration in higher education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 22, 7-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2017.11.002 [ Links ]

Kostygina, G., Tran, H., Binns, S., Szczypka, G., Emery, S., Vallone, D., & Hair, E. (2020). Boosting health campaign reach and engagement through use of social media influencers and memes. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2056305120912475 [ Links ]

Madathill, K. C., Rivera-Rodriguez, A. J., Greenstein, J. S., & Gramopadhye, A. K. (2015). Healthcare information on YouTube: A systematic review. Health Information Journal, 21(3), 173-194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458213512220 [ Links ]

Maraji's World. (2020, March 28). Different types of people now [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRXUlFjIm00

Marwick, A. E. (2015). You may know me from YouTube: (Micro-)celebrities in social media. In P. D. Marshall & S. Redmond (Eds.), A companion to celebrity (pp. 194-212). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118475089.ch18

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313 [ Links ]

MC Shem Comedian. (2020, May 22). Face mask [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwFKqLj8D8g

Miller, B. (2017). YouTube as educator: A content analysis of issues, themes and educational value of transgender-created online videos. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117716271 [ Links ]

Mookadam, F., Oz, M., Siddiq, T. J., Almader-Douglas, D., Crupain, M., & Khan, M. S. (2019). Impact of unauthorized celebrity endorsements on cardiovascular healthcare. Future Cardiology, 15(6), 387-390. https://doi.org/10.2217/fca-2019-0020 [ Links ]

Mr. Macaroni. (2020, April 19). Wahala in the society [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HyiEeUmMkTA.

Niu, S., Bartolome, A., Mai, C., & Ha, N. (2021). #StayHome #WithMe: How do YouTubers help with COVID-19 loneliness? In CHI '21: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15). https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445397

Oeldorf-Hirsch, A., & Sundar, S. S. (2015). Posting, commenting, and tagging: Effects of sharing news stories on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 240-249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.024 [ Links ]

Olapegba, P. O., Ayandele, O., Kolawole, S. O., Oguntayo, R., Gandi, J. C., Dangiwa, A. L., Ottu, I. F. A., & Iorfa, S. K. (2020). A preliminary assessment of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge and perceptions in Nigeria. medRxiv pre-print. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.11.20061408

Oludimu, T. O. (2019, March 27). Professional Nigerian YouTubers have to look outside YouTube to make money. Techpoint Africa. https://techpoint.africa/2019/03/27/ways-nigerian-youtubers-make-money/

Rosenberg, M., Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Kianersi, S., Fu, T., & Herbenick, D. (2021). Depression and loneliness during April 2020 COVID-19 restrictions in the United States, and their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56, 1221-1232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-02002-8 [ Links ]

Salyer, A. M., & Weiss, J. K. (2020). Real close friends: The effects of perceived relationships with YouTube microcelebrities on compliance. The Popular Culture Studies Journal, 8(1), 139-156. [ Links ]

Schäfer, M. S., & Taddicken, M. (2015). Mediatized opinion leaders: New patterns of opinion leadership in new media environments? International Journal of Communication, 9, 960-981. [ Links ]

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258-281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898 [ Links ]

Seo, M., & Hyun, K. D. (2018). The effects of following celebrities' lives via SNSs on life satisfaction: The palliative function of system justification and the moderating role of materialism. New Media & Society, 20(9), 3479-3497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817750002 [ Links ]

Senft, T. M. (2008). Camgirls: Celebrity and community in the age of social networks. Peter Lang. SisiYemmieTV. (2020, May 2). Lagos lockdown/A day in my life/Social distancing??? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qIr1bSgs2s

Smith, D. R. (2017). The tragedy of self in digitised popular culture: The existential consequences of digital fame on YouTube. Qualitative Research, 17(6), 699-714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117700709 [ Links ]

Sobande, F. (2017). Watching me watching you: Black women in Britain on YouTube. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(6), 655-671. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549417733001 [ Links ]

Sofian, F. A. (2020). YouTubers creativity in creating public awareness of COVID-19 in Indonesia: A YouTube content analysis. In 2020 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech) (pp. 881-886). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIMTech50083.2020.9211149

Song, H. (2018). The making of microcelebrity: AfreecaTV and the younger generation in neoliberal South Korea. Social Media + Society, 4(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118814906 [ Links ]

Starbird, K., & Palen, L. (2012). (How) will the revolution be retweeted? Information diffusion and the 2011 Egyptian uprising. In S. Poltrock, C. Simone, J. Grudin, G. Mark, & J. Riedl (Eds.), Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 7-16). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2145204.2145212

Tangwa, G. B., & Munung, N. S. (2020). COVID-19: Africa's relation with epidemics and some imperative ethics considerations of the moment. Research Ethics, 16((3-4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016120937391 [ Links ]

Tolbert, A. N., & Drogos, K. L. (2019). Tweens' wishful identification and parasocial relationships with YouTubers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02781 [ Links ]

Tomi's Colour Pavilion. (2020, March 19). Is this a cure for corona virus? Find out [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8gfCwr5eTI

Toromade, S. (2020, March 20). Timeline of coronavirus cases in Nigeria. Pulse. https://www.pulse.ng/news/local/coronavirus-timeline-and-profile-of-cases-in-nigeria/k9p6lbk

Turcotte, J., York, C., Irving, J., Scholl, R. M., & Pingree, R. J. (2015). News recommendations from social media opinion leaders: Effects on media trust and information seeking. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(5), 520-535. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12127 [ Links ]

Udodiong, I. (2019, February 8). Here is how Nigerians are using the internet in 2019. Pulse. https://www.pulse.ng/bi/tech/how-nigerians-are-using-the-internet-in-2019/kz097rg

Umeh, D. (2020, April 19). Can we talk about this???!!! [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GQ00RvYilNc.

Uzuegbunam, C. E. (2017). Between media celebrities and the youth: Exploring the impact the of emerging celebrity culture on the lifestyle of young Nigerians. Mgbakoigba: Journal of African Studies, 6(2), 130-141. [ Links ]

Velasquez, A. (2012). Social media and online political discussion: The effect of cues and informational cascades on participation in online political communities. New Media & Society, 14, 1286-1303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812445877 [ Links ]

Vosoughi, S., Roy, A., & Aral, D. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559 [ Links ]

Wegener, C., Prommer, E., & Linke, C. (2020). Gender representations on YouTube: The exclusion of female diversity. M/CJournal, 23(6). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2728 [ Links ]

Winter, S., & Neubaum, G. (2016). Examining characteristics of opinion leaders on social media: A motivational approach. Social Media + Society, 2(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116665858 [ Links ]

Wohn, D. Y., & Bowe, B. J. (2016). Micro agenda setters: The effect of social media on young adults' exposure to and attitude toward news. Social Media + Society, 2(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115626750 [ Links ]

Wonodi, C., Obi-Jeff, C., Adewumi, F., Keluo-Udeke, C., Gur-Aire, R., Krubiner, C., Jaffe, E. F., Bamiduro, T., Karron, R., & Faden, R. (2022). Conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19 in Nigeria: Implications for vaccine demand generation communications. Vaccine, 40, 2114-2121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.005 [ Links ]

Yeku, J. (2016). Akpos don come again: Nigerian cyberpop hero as trickster. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 28(3), 245-261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2015.1069735 [ Links ]

YouTube. (2020a, March 16). Protecting our extended workforce and community. https://blog.youtube/news-and-events/protecting-our-extended-workforce-and

YouTube. (2020b, June 25). YouTube during COVID-19. https://youtube.com/trends/articles/what-it-means-to-stayhome-on-youtube

Zimmermann, D., Noll, C., Grafter, L., Hugger, K., Braun, L. M., Nowak, T., & Kaspar, K. (2020). Influencers on YouTube: A quantitative study on young people's use and perception of videos about political and societal topics. Current Psychology, 41, 68086824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01164-7 [ Links ]

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr Matthew Heinz for invaluable feedback during the writing of this article.