Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The African Journal of Information and Communication

On-line version ISSN 2077-7213

Print version ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.24 Johannesburg 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/10539/28661

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Assessing the Social Media Maturity of a Community Radio Station: The Case of Rhodes Music Radio in South Africa

Mudiwa A. GavazaI; Noel J. PearseII

IFreelance Business Writer and Radio Presenter; Graduate, Rhodes Business School, Rhodes University, Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6104-3886

IIProfessor, Rhodes Business School, Rhodes University, Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7583-984

ABSTRACT

Social media has become a major factor within the operations and functions of radio stations. This study used a social media maturity model (SMMM), developed from available literature, to assess the social media maturity of a South Africa community radio station, Rhodes Music Radio (RMR). The study found that RMR had a level 3 rating on a 5-level maturity scale, indicating that it was quite, but not yet fully, mature in its social media use. In addition to outlining the research and its findings, this article makes recommendations for how the station could increase the maturity of its social media use.

Keywords: social media, community radio, social media maturity model (SMMM), Rhodes Music Radio (RMR), Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa

1. Introduction

The aim of the research on which this article is based was to develop and implement a social media maturity model (SMMM) to assess a community radio station's use of social media. Rhodes Music Radio (RMR) is a non-profit community radio station based on the campus of Rhodes University in Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa (RMR, 2007). The station services the general Makhanda area, which, according to the World Population Review (2019), has a population in excess of 90,000. The station operates within a 50 km radius of its location in the town (RMR, 2015). RMR uses social media in a number of different ways. Social media are sources of news content for shows, a channel of communication for the station's listeners, a mode of internal communication for RMR staff, and a tool for marketing the brand of the station. Almost all operational departments at the station use social media in some way.

Community radio and social media

Jankowski (2003, p. 7) places community radio under a broader category of community media, which includes "a diverse range ofmediated forms of communication: electronic media such as radio and television, print media such as newspapers and magazines, and electronic network initiatives which embrace characteristics of both traditional print and electronic media". The uniqueness and contribution of community radio broadcasters is partly reflected in the values that they promote. Through a meta-analysis of the literature, Order (2015) identified these distinguishing values as access, diversity, alternative, independence, representation and participation. In addition, the content of community radio has unique features, which are valued by its listeners. Lewis (2000) has noted that, despite the growing preference for visual media, radio remains important in the personal lives of listeners. This may be explained by the unique offerings of radio in comparison to other media, such as: the appeal of radio music (MacFarland, 2016), the affinity of radio soap opera with storytelling traditions (Makoye, 2006), the growing popularity of radio talk shows (Owen, 2018), and the opportunity that radio provides to the audience to be the co-producers of radio (Hendy, 2013), or to be citizen journalists (Atton, 2003).

Community radio typically has communitarianism (Brevini, 2015), the facilitation of social inclusion (Correia, Vieira & Aparicio, 2019), or the development and maintenance of a local community identity (Scifo, 2015) as its primary purpose. Therefore, central to its raison d'etre is the building of a relationship between the station and the local community, particularly if community radio is viewed as a communication system rather than as a distribution system, allowing listeners not only to hear, but also to speak (Hendy, 2013). Community radio can also serve a number of other purposes, including community development (Wabwire, 2013), the promotion of democracy and citizen participation (Barlow, 1988; Mhagama, 2016) and the promotion of socio-cultural cohesion (Correia, Vieira & Aparicio, 2019; Rodríguez, 2005), but relationship-building remains a central characteristic.

Looking specifically at the South African context, the 1993 Independent Broadcasting Authority Act (IBA Act) made provision for three types of radio broadcasters, namely public, commercial and community services (RSA, 1993). Within a few years of the Act being promulgated, around 100 community radio stations had received operating licences (Sparks, 2009; Tacchi, 2003), and by 2007, 152 of South Africa's 191 licensed radio stations were classified as community services, reaching an estimated 6.5 million listeners (Da Costa, 2012). These radio stations were either serving a localised geographic community, or a community that had a common interest (Tacchi, 2003). (The IBA Act was repealed, and its provisions on community broadcasting replaced, by the Electronic Communications Act (ECA) of2005 (RSA, 2005).)

Subsequently, community radio in South Africa has been found to serve as an effective way to:

• raise awareness about health-related issues (Hlongwana, Zitha, Mabuza & Maharaj, 2011; Mawokomayi & Osunkunle, 2019; Medeossi, Stadler & Delany-Moretlwe, 2014).

• inform and empower women (Fombad & Jiyane, 2019; Oduaran & Nelson, 2019).

• build communities (Mawokomayi & Osunkunle, 2019; Tacchi, 2002).

• provide a vehicle for participatory communication amongst previously disenfranchised communities (Megwa, 2007; Olorunnisola, 2002).

• facilitate access for community members to information and communication technology (Megwa, 2007).

However, Sparks (2009) observes that there is some concern that the essence of community radio in South Africa has been eroded by financial pressures and the adoption by many stations of a more commercialised operating model. Observing international trends in emerging community radio, Da Costa (2012) cautions that there is a tendency for the original purpose of community radio to be eroded when funding sources and models change.

As social media has emerged, it has been increasingly integrated into the activities of radio, with journalists adopting social media as a tool of their trade (Jordaan, 2013). For example, Rooke and Odame (2013) found that community radio hosts in Canada were using blogs primarily to generate a larger audience base and to interact and connect with listeners. In community radio in South Africa, there has been an increasing but uneven use of social network sites, and even a negative correlation between the number of listeners and the number of followers on social media (Bosch, 2014). This anomaly is partly explained by the economic inequalities of South African society, with some of the larger radio stations targeting poorer communities that are unable to afford internet connectivity (Bosch, 2014). Nevertheless, social media provides an added dimension to the relationship that a radio station has with its local community, as it represents an additional tool with which to build these relationships through the two-way communication that it enables.

Furthermore, Bosch (2014) found that audiences already on social media tended to have greater access to, and participation in, community radio, with, for example, their messages being read on air. She also notes that the virtual and distributed nature of these networks is redefining the notion of a community, beyond geographic confines. In addition to building a relationship with their listener base, broadcasters cannot ignore the potential of social media to complement fundraising efforts (Rooke & Odame, 2013) and to generate an additional advertising revenue stream (Albarran & Moellinger, 2013; Lietsala & Sirkkunen, 2008). However, this places greater demands on broadcasters, who must continue to pay attention to the quality of their radio broadcasting as well as effectively integrate their use of social media.

Quality in radio

Radio stations derive their assessment of quality from three main dimensions (Ngcezula, 2008), namely: (1) content produced by the station, such as programming, jingles and music played; (2) the style and overall effectiveness of radio hosts and presenters; and (3) listenership, which determines, in part, the advertising revenue potential of the station.

In South Africa, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) is mandated by legislation to regulate "the telecommunications, broadcasting and postal industries in the public interest and ensure affordable services of a high quality for all South Africans" (ICASA, n.d.). ICASA fulfils several functions, including receiving and resolving complaints (ICASA, n.d.). Largely due to these regulatory requirements, the quality of radio programming receives a great deal of attention. A typical approach to monitoring the quality of programmes is for executive producers or management to conduct "snoop sessions", which involve listening to the station's content (Radio Talent, 2013). In addition, focus group discussions amongst shows' listeners are held to assess the quality of the on-air content from a listener's point of view (Freitas et al., 1998).

Media organisations are still trying to devise ways to integrate, fully and effectively, the use of social media into their operations (Alejandro, 2010). This is one reason why journalists and media organisations follow, or monitor, each other's activities online. They hope to identify best practices, or new ways of using these platforms (Harper, 2010). Despite some interest in the management of quality in radio, relatively little research has been done on quality management in media organisations. It is not surprising, then, that only a limited number of research studies have been conducted to investigate quality aspects of the use of social media, or online activity in radio. To date, research has focused on issues such as: accessing radio programming using online platforms (Evans & Smethers, 2001); using social media to grow radio listenership (Greer & Phipps, 2003); making radio more personal through social media (Lüders , 2008); investigating youth attitudes towards traditional media in the age of social media (Tapscott, 2009); exploring the place of traditional radio stations in the age of social media and online streaming services (e.g., Pandora, Apple Music and Spotify) (Winans, 2012); and determining how radio stations should be conducting themselves on social media (Resler, 2016).

2. Models for assessing organisational maturity and social media maturity

Operational excellence and organisational maturity

As one aspect of the quality process of an organisation, operational excellence can be described as the consistent and reliable execution of the business strategy (Wilson Perumal & Company, 2013). Organisational maturity is referred to when measuring the level of quality, and is defined by Torres (2014, p. 1) as "a measure of an organization's readiness and capability expressed through its people, processes, data and technologies and the consistent measurement practices that are in place". Models of organisational maturity have been developed, with their origins in the software industry (Wendler, 2012). These models are presented in the form of a matrix that is made up of five or six discrete and cumulative levels (or stages) of maturity, against which varies categories of performance are measured (Wendler, 2012).

While the publication of maturity models is still dominated by the software industry, there has been a rapid growth in the number of areas where maturity models are applied (Tarhan, Turetken & Reijers, 2016; Wendler, 2012) and the development of more generic models such as the business process orientation (BPO) maturity model (Tarhan et al., 2016). The BPO maturity model identifies five levels of maturity or quality, naming them as follows: ad hoc; defined; linked; integrated; and extended (Lockamy & McCormack, 2004). A second generic model, the capability maturity model (CMM) has been adapted from the BPO maturity model (Lockamy & McCormack, 2004, p. 276) and is a five-level generic maturity model used to assess an organisation's ability or capacity to deal with any type of proposed change (Perkins, 2012). According to Perkins (2012, p. 4), "CMM describes the behaviours, practices and processes of an organisation that enables them to reliably and sustainably produce required outcomes." The model adopts a multi-dimensional approach to assess an organisation's ability to adapt to a proposed change (Perkins, 2012). The basic premise of a third model-the organisational IT maturity (OITM) model- is that it specifically examines an organisation's ability to invest in, or implement, information technology solutions (Ragowsky, Licker & Gefen, 2012). This model has six levels, rather than the typical five, making use of a "level 0". These levels go from "ignorant" at level 0 to "aware" to "willing" to "trusting" to "accepting" and ultimately to "responsible" at level 5 (Ragowsky et al., 2012).

Organisational maturity models incorporating social media

The social organisation model (Campbell & Gray, 2014), developed by PMWorks in Australia, is used to assess the likelihood of success when incorporating social media into the operations of an organisation. The basic premise of the model is that the business must first understand the model of social organisation which prevails, before implementing social media, as a failure to do so may "hamper or possibly kill the successful uptake of social media within the organisation" (Campbell & Gray, 2014, p. 9). The five stages, or levels of the social organisation model are: (1) traditional: traditional hierarchical communication structure; (2) decentralised: no centre of power and influence; (3) hub and spoke: communication occurs with a common purpose; (4) dandelion: multiple hub and spoke networks working towards a common purpose or goal; and (5) honeycomb: fully integrated communication without hierarchical structure but with a common purpose (Campbell & Gray, 2014). The least favourable of the five levels is the first one-traditional-which hinders the adoption of social media and is focused on hierarchical communication, while in the fifth level-honeycomb-an organisation is fully adapted to social media (Campbell & Gray, 2014).

Social media maturity model (SMMM)

Organisations are increasingly using social media, in recognition of its strategic importance for marketing, communication and other purposes, and yet there is a paucity of research on social media management in organisations (Chung, Andreev, Benyoucef, Duane & O'Reilly, 2017; Duane & O'Reilly, 2016). PMWorks has put forward a social media maturity model that is focused specifically on the employees of an organisation and how much they are involved with social media in their lives, both personally and professionally (Campbell & Gray, 2014). Given its focus on employee use, the relevance of the work of Campbell and Gray (2014) to this study was recognised. The five levels are labelled and defined as follows (Campbell & Gray, 2014):

• Level 1: Ad hoc or absent: Some individuals are literate in social media and use it for their own personal purposes, mostly, or even exclusively, outside of work.

• Level 2: Isolated users connected: Some individuals use social media to connect with other workers within the organisation for work and/or social purposes. While nothing is officially organised, experimentation and use are tolerated within the organisation.

• Level 3: Emergent community: An application for social media is identified and implemented within a group or in a specific project. This may emerge from organic growth, or an executive sponsor (e.g., marketing), or to support communication efforts associated with a specific project.

• Level 4: Community: Organisation-wide models and tools are broadly deployed for managing social media content and platforms, and some metrics are implemented. Social media is used to support the management of cultural change at the corporate level.

• Level 5: Fully networked: All employees are connected to the organisational social network and have a recognised role. Social media values and practices are an embedded part of the culture, and individuals operate in multiple relationships across the organisation. The inclusion of metrics and determining the return on investment are an accepted part of the model. Social media is an accepted part of the change management tool set and/or marketing mix.

3. Development and application of an SMMM for community radio

It was decided that the organisational maturity of Rhodes Music Radio's use of social media should be rated using an adapted version of the Campbell and Gray (2014) SMMM, with the adaptations drawing on other models from the literature outlined above (Lockamy & McCormack, 2004; Perkins, 2012; Ragowsky et al., 2012).

Five-level scale

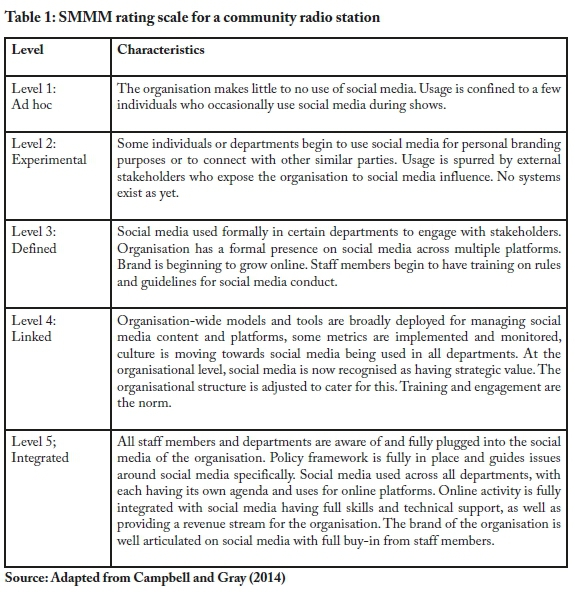

The adapted SMMM has a five-level scale, with 1 being the lowest level of maturity and 5 being the highest (Lockamy & McCormack, 2004; Ragowsky et al., 2012). Each level is matched with a general description of characteristics, as adapted from the Lockamy and McCormack (2004) BPO maturity model and the Campbell and Gray (2014) SMMM. The levels of these models differ somewhat. Lockamy and McCormack (2004) include an experimental level between Campbell and Gray's (2014) levels of ad hoc and defined. This level was included to provide a more granular distinction of levels at the lower end of maturity. Furthermore, Lockamy and McCormack's (2004) extended level, which describes multi-firm networks, was not included, given the interest in the maturity of social media use in a single entity, namely RMR. The levels, as outlined in Table 1 in ascending order of maturity from 1 to 5, are therefore: ad hoc; experimental; defined; linked; and integrated.

This SMMM uses model descriptions at each level to describe the general level of maturity (Campbell & Gray, 2014; Ragowsky et al., 2012). With these descriptions as a base, the SMMM uses more specific descriptions at each level of maturity for the specific factor to be investigated.

O rganisational spheres

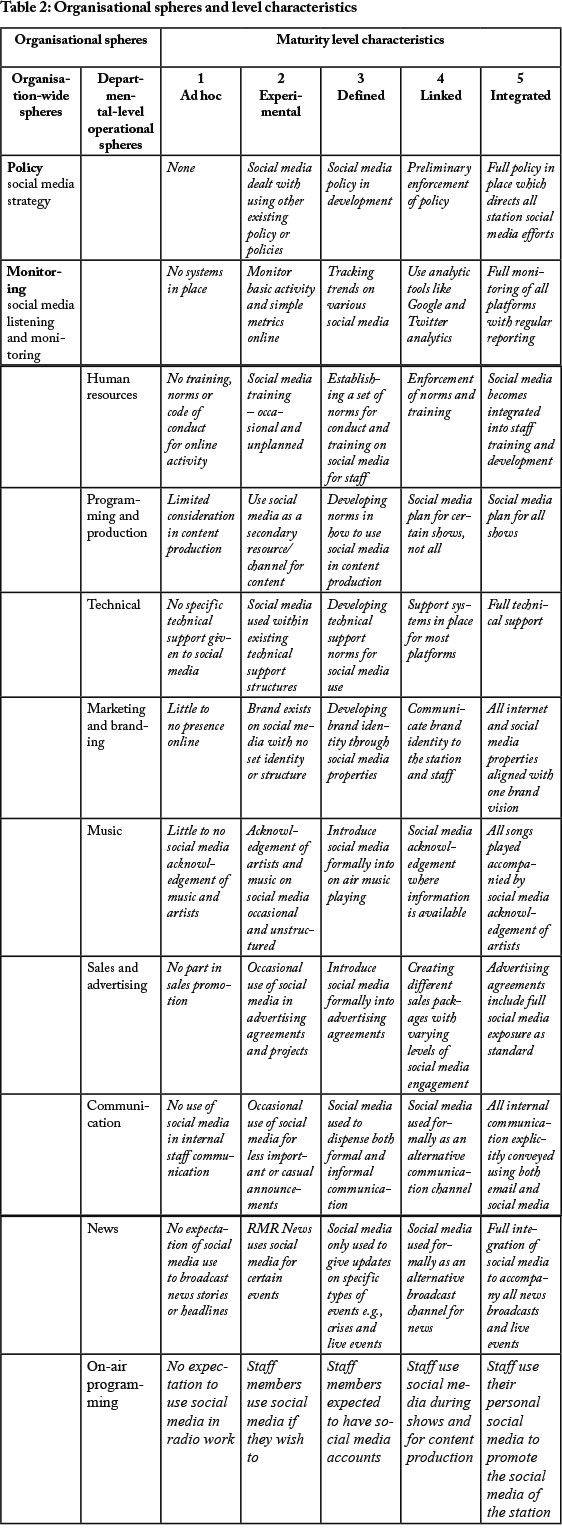

The organisational spheres chosen for application of the model were:

• organisation-wide spheres: (1) policy and (2) monitoring.

• all the RMR departmental operational spheres, namely: human resources, programming and production, technical, marketing and branding, music, sales and advertising, communication, news, and on-air programming.

Data collection

The model was applied to RMR using two sources of data, namely the RMR's "Operational Policy" document and 14 interviews with RMR staff, including: the station manager, all nine functional managers, and four presenters. All the interviews were conducted within a month and face-to-face, and-with the permission of the interviewees-were audio recorded. The sources of information for developing the SMMM were therefore RMR staff members, who were asked questions during the semi-structured interviews that were customised to their area of functioning. For the most part, the sources had an intimate knowledge of how their department was making use of social media, or of how their department's efforts were contributing to the overall organisation-wide social media use of the station.

Deductive thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998; Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to analyse the data. In accordance with the model, the assessment was focused on finding out which systems the station has in place to make effective use of social media-both generally and within individual departments, and at what level of maturity. For two organisation-wide spheres, as well as for each department, the data collected was summarised and compared to the SMMM rating scale descriptors as set out in Table 1, to reach a judgement on the level of maturity. In addition, based on the summaries, short descriptions of level characteristics were formulated. Table 2 summarises the SMMM's organisational spheres and maturity level characteristics.

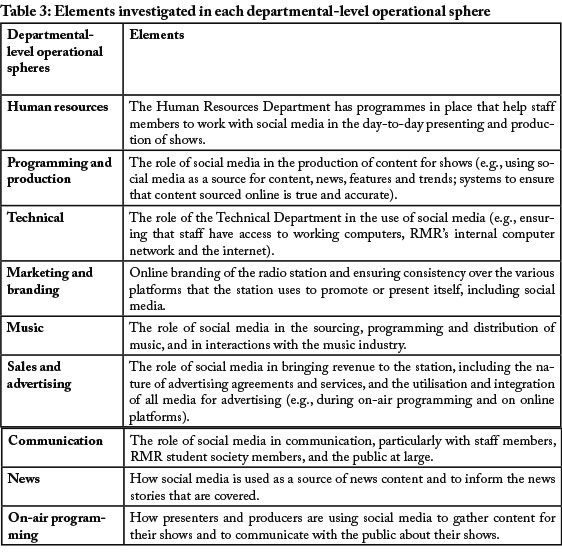

Table 3 lists the departments that constitute the operations of RMR and describes the elements with relevance to the SMMM that were investigated in each departmental sphere. After first assessing the social media maturity of each department, an aggregate maturity level for the whole organisation was then determined.

4. Findings

Organisation-wide spheres: policy and monitoring

It was found that RMR did not have a formal social media policy in place, but had other working documents that it used as guidelines. The main document used for the day-to-day running of the station was an Operational Policy document that was formulated in 2014. Regarding the use of social media at the station, the Operational Policy was used as a guideline for how staff should conduct themselves online, both professionally and personally. The policy indicated that staff members should not act in ways that bring the name of the station into disrepute or use language on air that is derogatory, for example. This policy originally applied to the general conduct of staff members at RMR, but had since applied to the conduct of staff members in their use of social media. A Social Media Policy was being developed at the time of the field research and still had to be finalised and implemented.

As a station, RMR was using Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. In terms of administration of the different social media accounts, the following portfolios had administrative access on behalf of the station: the Station Manager, the Deputy Station Manager, Communications, Marketing and Brands, and Social Media. When live events were posted, the content for the various accounts was verified by the Social Media Manager.

RMR was monitoring its performance on social media using the analytical tools made available by the different networks, and through feedback received by the station in the form of word-of-mouth and written comments. However, the station had no benchmarks in place to gauge the performance of social media posts, and no formal or systematic way of monitoring the social media activities of staff members to ascertain the quality and integration of social media use.

Departmental-level operational spheres

Human resources

Internally, staff members were expected to participate as much as possible on social media, in ways that helped to promote the station and its programming. However, staff had not received any formal training from RMR on social media use. No training was offered and no guidelines on responsible behaviour were available. Instead, staff had learnt through their own research and experience. Presenters followed national and local media organisations that always seemed to be up to date with what was happening nationally, and that updated their social media platforms frequently. Individuals with national profiles in radio were followed, as well as some with a local profile.

Programming and production

RMR considered social media to be a major source of content for its programming. The production team tended to rely on credible or established news outlets and media organisations to verify the content of stories sourced from social media, and the Production Manager controlled the type of content that was aired, by approving show content plans before shows went on air.

Presenters recognised that social media helped them to stay abreast of trends and the general state of society. One interviewee was of the view that the public's expectation was that presenters "should be informed about what is going on in the society, since they are the people who are a voice for the people." Another interviewee noted that listeners expected presenters to interact with them online when presenting their shows on radio. However, interviewees were of the view that listeners expected presenters to stay neutral on radio and in social media, since they were viewed as journalists. As one interviewee stated: "One needs to be unbiased and I find that my interactions on social media remain consistent whether I'm dealing on a personal or professional level."

Technical

The technical team was responsible for setting up equipment, including ensuring that computers are in working condition and that they can access the internet. While the technical team members were trained as sound technicians, with the expanding scope of their work, they had to develop expertise in the areas of IT, networking and engineering as well.

Marketing and branding

RMR used Twitter, Instagram and Facebook to communicate and market its brand. The station also derived some benefit for its brand through the personal social media accounts and networks of RMR staff. However, it was difficult to monitor how staff members carried the RMR brand online. The Marketing Manager said: "There are no systems in place to help maintain the values, mission and brand image of RMR. There is room for improvement when it comes to RMR's efforts to grow its brand using social media."

Music

RMR's Music Department engaged with the music industry using social media as a channel of communication. Formal communication with public relations companies promoting songs took place through email. Music submissions were mainly done using digital submissions or email, with the sending of physical CDs to the station "becoming less by the week". It was not possible for songs to be added to RMR's library from social media interaction, but when songs were play listed or added to the music library, this was acknowledged on Twitter.

Recording companies and artists tended to interact with RMR on their various social media platforms when their music was played on RMR. Twitter seems to be the music industry's preferred platform, because of its immediacy and the capability to gauge trends on this platform.

Sales and advertising

While potential advertisers were made aware of RMR's presence and engagement on social media through statistics and website links, the main channel for advertising was on-air advertising, and RMR did not charge for advertising on its social media, but offered it as an added benefit to advertisers. Therefore, the radio station did not generate any revenue directly from its social media platforms. Furthermore, competitions were used as a vehicle to get people to view RMR's social media platforms and thereby to view the advertising content placed there.

Communication

The Communications Manager highlighted that the official channel for internal communication for staff members was email, but recently this had been extended to the use of social media: a special Facebook group was established for staff. Email was still used for communication with the RMR Club. For external communications, RMR had established a social media presence and now had to work on increasing the level of interaction with its online platforms.

News

RMR used social media as a source of news and content. RMR recognised that social media can be a biased news source, but there were no formal systems in place at RMR to check the credibility of sources. However, the news team tried to fact check stories before reporting on them. RMR News operated as a broadcast news team with on-air bulletins being the only way in which RMR conveyed news to people. RMR did not publish news anywhere else.

Overall assessment

Table 4 provides a summary of the assessment of RMR's social media maturity. According to the model, the station was assessed as being at level 3 maturity overall in its social media use, with room for improvement. In Table 1, a level 3 maturity was described as "defined", meaning that social media was used formally in some departments. As set out in Table 4, three departments were found to be at level 3, and five at level 4, with only the Technical Department rated at level 2 (as skills related to social media support were still being developed in that department). Furthermore, the organisation had a formal presence across multiple social media platforms, and there was evidence to suggest that the station's brand was beginning to grow online. RMR had also begun tracking the trends in its social media presence. Furthermore, consistent with the level 3 descriptor, staff members were being trained in social media use, and there were rules and guidelines related to social media conduct, even though a formal policy on social media was still to be finalised.

5. Recommendations and future research

We now provide our recommendations for how RMR can increase its social maturity level, followed by recommendations for further research.

Technical skills

The department that required the most urgent attention was the Technical Department, to develop its members' capacity so that they could provide the required support for social media. This required creating a position responsible for computer-related technical support, and the recruitment of someone with the relevant skills to fill the post.

Internal capacity development

To develop capacity internally, the station needed to urgently finalise and endorse its Social Media Policy. Thereafter, RMR staff had to be trained on the policy and how to apply it properly in their work. Finally, once staff were informed of the Social Media Policy and formally trained in the use of social media, they had to be encouraged to become more involved in the social media of the station, by following the various RMR accounts and engaging with listeners and other staff members on these platforms.

Integration of social media into activities

Once internal social media capacity had been developed, the station needed to find ways to better integrate social media into its activities. First, it had to find ways to connect more frequently with the Rhodes University and Makhanda communities, as these two audiences formed the main listener base for the station's estimated 3,000 listeners. RMR also needed to find ways to convert its social media following into listeners of its broadcast programming. Marketing through live broadcast events that are also promoted through social media could be an effective means to achieve this. Furthermore, RMR could try using new social media platforms such as Snapchat and Google Plus, to complement its traditional Facebook, Twitter and Instagram platforms. These recommendations highlight the need for RMR to adopt a more strategic and integrated approach in its use of a combination of radio and social media, to provide a more holistic set of media to its audience.

Future research

The SMMM developed in this study seemed to be appropriate for assessing the social media maturity level of RMR and appeared to be practically useful in identifying areas for the station's potential improvement. However, the research was of limited scope given that it involved only one community radio station. It is therefore recommended that further research be undertaken with the same model at other community radio stations, to test the utility of the model in other contexts.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on research conducted by the lead author Gavaza for his MBA dissertation, which was completed under the supervision of the second author, Pearse. This article also draws on the contents of a paper presented by the authors at the World Media Economics and Management Conference, 6-9 May 2018, Cape Town.

References

Albarran, A. B., & Moellinger, T. (2013). Traditional media companies in the US and social media: What's the strategy? In M. Friedrichsen (Ed.), Handbook of social media management (pp. 9-24). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28897-5 2 [ Links ]

Alejandro, J. (2010). Journalism in the age of social media. Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Atton, C. (2003). What is alternative journalism? journalism, 4(3), 267-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849030043001 [ Links ]

Barlow, W. (1988). Community radio in the US: The struggle for a democratic medium. Media, Culture & Society, 10(1), 81-105. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344388010001006 [ Links ]

Bosch, T. (2014). Social media and community radio journalism in South Africa. Digital Journalism, 2(1), 29-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.850199 [ Links ]

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Brevini, B. (2015). Public service and community media. In The international encyclopedia of digital communication and society (1st ed.), (pp. 1-9). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118767771.wbiedcs045 [ Links ]

Campbell, C., & Gray, P. (2014). Social media for change management. St. Leonards, Australia: PMWorks. [ Links ]

Chung, A. Q Andreev, P., Benyoucef, M., Duane, A., & O'Reilly, P. (2017). Managing an organisation's social media presence: An empirical stages of growth model. International Journal of Information Management, 37(1), 1405-1417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.10.003 [ Links ]

Correia, R., Vieira, J., & Aparicio, M. (2019). Community radio stations sustainability model: An open-source solution. Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 17(1), 29-45. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.17.L291 [ Links ]

Da Costa, P. (2012). The growing pains of community radio in Africa: Emerging lessons towards sustainability. Nordicom Review, 33(Special Issue), 135-148. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2013-0031 [ Links ]

Duane, A., & O'Reilly, P. (2016). A stage model of social media adoption. Journal of Advances in Management Sciences & Information Systems, 2(2016), 77-93. https://doi.org/10.6000/2371-1647.2016.02.07 [ Links ]

Evans, C. L., & Smethers, J. S. (2001). Streaming into the future: A Delphi study of broadcasters' attitudes toward cyber radio stations. Journal of Radio Studies, 8(1), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506843jrs08014 [ Links ]

Fombad, M. C., & Jiyane, G. V. (2019). The role of community radios in information dissemination to rural women in South Africa. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(1), 47-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000616668960 [ Links ]

Freitas, H., Oliveira, M., Jenkins, M., & Popjoy, O. (1998). The focus group, a qualitative research method. ISRC Working Paper 010298. Information Systems Research Group, Merrick School of Business, University of Baltimore.

Gavaza, M. A. (2017). Assessing the organisational maturity level of Rhodes Music Radio with the introduction of social media. Master's Thesis, Rhodes University, Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa. [ Links ]

Greer, C., & Phipps, T. (2003). Noncommercial religious radio stations and the web. Journal of Radio Studies, 10(1), 17-32. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506843jrs10014 [ Links ]

Harper, R. A. (2010). The social media revolution: Exploring the impact on journalism and news media organizations. Inquiries Journal: Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities, 2(3), 1-4. [ Links ]

Hendy, D. (2013). Radio in the global age. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Hlongwana, K. W., Zitha, A., Mabuza, A. M., & Maharaj, R. (2011). Knowledge and practices towards malaria amongst residents of Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 3(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v3i1.257 [ Links ]

Independent Communication Authority of South Africa (ICASA). (n.d.). Our mandate [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.icasa.org.za/pages/our-mandate

Jankowski, N. (2003). Community media research: A quest for theoretically-grounded models. Javnost - The Public, 10(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2003.11008818 [ Links ]

Jordaan, M. (2013). Poke me, I'm a journalist: The impact of Facebook and Twitter on newsroom routines and cultures at two South African weeklies. Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies, 34(1), 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560054.2013.767421 [ Links ]

Lietsala, K., & Sirkkunen, E. (2008). Social media. Introduction to the tools and processes of participatory economy.Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press. [ Links ]

Lewis, P. M. (2000). Private passion, public neglect: The cultural status of radio. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 3(2), 160-167. https://doi.org/10.1177/136787790000300203 [ Links ]

Lewis, P. M., & Booth, J. (1989). The invisible medium: Public, commercial, and community radio. New York: Macmillan Education. [ Links ]

Lüders, M. (2008). Conceptualising personal media. New Media & Society, 10(5), 683-702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808094352 [ Links ]

Lockamy, A., & McCormack, A. L. K. (2004). The development of a supply chain management process maturity model using the concepts of business process orientation. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 9(4), 272-278. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540410550019 [ Links ]

MacFarland, D. T. (2016). Contemporary radio programming strategies. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315443522 [ Links ]

Mawokomayi, B., & Osunkunle, O. O. (2019). Listeners' perceptions of Forte FM's role in facilitating community development in Alice, South Africa, Critical Arts, 33(1), 88-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1631364 [ Links ]

Mhlanga, B. (2016). The return of the local: Community radio as dialogic and participatory. In A. Salawu & M. B. Chibita (Eds.), Indigenous language media, language politics and democracy in Africa (pp. 87-112). London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/97811375473095 [ Links ]

Makoye, H. F. (2006). Tale-telling tradition and popularity of radio soap opera in Tanzania: The case of Twende na Wakati. Utafiti Journal, 7(1), 91-99. [ Links ]

Medeossi, B. J., Stadler, J., & Delany-Moretlwe, S. (2014). 'I heard about this study on the radio': Using community radio to strengthen good participatory practice in HIV prevention trials. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 876-883. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-876 [ Links ]

Megwa, E. R. (2007). Community radio stations as community technology centers: An evaluation of the development impact of technological hybridization on stakeholder communities in South Africa. Journal of Radio Studies, 14(1), 49-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10955040701301847 [ Links ]

Mhagama, P. (2016). The importance of participation in development through community radio: A case study of Nkhotakota community radio station in Malawi. Critical Arts, 30(1), 45-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1164384 [ Links ]

Ngcezula, A. T. (2008). Developing a business model for a community radio station in Port Elizabeth: A case study. Master's thesis, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. [ Links ]

Oduaran, C. & Nelson, O. (2019). Community radio, women and family development issues in South Africa: An experiential study. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(7), 102-112. [ Links ]

Olorunnisola, A. A. (2002) Community radio: Participatory communication in post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Radio Studies, 9(1), 126-145. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506843jrs090111 [ Links ]

Order, S. (2015). Towards a contingency-based approach to value for community radio. Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 13(1-2), 121-138. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.13.1-2.1211 [ Links ]

Owen, D. (2018). Who's talking? Who's listening? The new politics of radio talk shows. In S. C. Craig (Ed.), Broken contract? Changing relationships between Americans and their government (pp. 127-146). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429502002-9 [ Links ]

Perkins, C. (2012). Organisational change management maturity. Unpublished report for the CMI White Paper. Sydney: Change Management Institute. [ Links ]

Radio Talent (2013). Walking on air: How to be a radio presenter: Volume 1 (media success). Los Gatos, CA: Smashwords. [ Links ]

Ragowsky, A., Licker, P. S., & Gefen, D. (2012). Organizational IT maturity (OITM): A measure of organizational readiness and effectiveness to obtain value from its information technology. Information Systems Management. 29(2), 148-160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2012.662104 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). (1993). Independent Broadcasting Authority Act (IBA Act), No. 153 of 1993. Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/za/za064en.pdf

RSA. (2005). Electronic Communications Act (ECA), No. 6 of2005. Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/za/za082en.pdf

Resler, S. (2016, June 10). Here's what your radio station should be sharing on social media. Jacobs Media Strategies [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jacobsmedia.com/heres-what-your-radio-station-should-be-sharing-on-social-media

Rhodes Music Radio (RMR). (2007). Constitution. Unpublished internal policy document. Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa: Rhodes Music Radio.

RMR. (2015). Rhodes Music Radio business model. Unpublished management strategy document. Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa: Rhodes Music Radio.

RMR. (2015). About us [Web page]. Retrieved from http://www.rhodesmusicradio.co.za/about-us/

Rodríguez, J. M. R. (2005). Indigenous radio stations in Mexico: A catalyst for social cohesion and cultural strength. Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 3(3), 155-169. https://doi.org/10.1386/rajo.3.3.155 1 [ Links ]

Rooke, B., & Odame, H. H. (2013). 'I have to blog a blog too?' Radio jocks and online blogging. Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 20(1), 35-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376529.2013.777342 [ Links ]

Scifo, S. (2015). Technology, empowerment and community radio. Revista Mídia e Cotidiano, 7(7), 84-111. https://doi.org/10.22409/ppgmc.v7i7.9754 [ Links ]

Sparks, C. (2009). South African media in transition. Journal of African Media Studies, 1(2), 195-220. https://doi.org/10.1386/jams.1.2.195/1 [ Links ]

Tacchi, J. (2002). Transforming the mediascape in South Africa: The continuing struggle to develop community radio. Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture and Policy, 103(1), 68-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0210300110 [ Links ]

Tacchi, J. (2003). Promise of citizens' media: Lessons from community radio in Australia and South Africa. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(22), 2183-2187. [ Links ]

Tapscott, D. (2009). Grown up digital: How the net generation is changing your world. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Tarhan, A., Turetken, O., & Reijers, H. A. (2016). Business process maturity models: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology, 75(2016), 122-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2016.01.010 [ Links ]

Torres, C. (2014, October 31). Understanding organizational maturity [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://blogs.vmware.com/management/author/torresc

Wabwire, J. (2013). The role of community radio in development of the rural poor. New Media and Mass Communication, 10, 40-47. [ Links ]

Wendler, R. (2012). The maturity of maturity model research: A systematic mapping study. Information and Software Technology, 54(12), 1317-1339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2012.07.007 [ Links ]

Wilson Perumal & Company (2013, May 10). A better definition of operational excellence [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.wilsonperumal.com/blog/a-better-definition-of-operational-excellence

Winans, S. (2012, April 11). Radio and social media [Blog post]. Social Media Sun. Retrieved from http://socialmediasun.com/radio-and-social-media

World Population Review (2019). Population of cities in South Africa [Web page]. Retrieved from http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/south-africa-population/cities