Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The African Journal of Information and Communication

On-line version ISSN 2077-7213

Print version ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.23 Johannesburg 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/10539/27536

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Asymmetry in South Africa's Regulation of Customer Data Protection: Unequal Treatment between Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) and Over-the-Top (OTT) Service Providers

Stanley Shanapinda

Research Fellow, Optus La Trobe Cyber Security Research Hub, La Trobe University, Melbourne; and Research Associate, LINK Centre, University of the Witwatersrand ( Wits), Johannesburg. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3961-2306

ABSTRACT

This article examines the asymmetry that currently exists in South Africa in the regulatory treatment of customer data usage by mobile network operators (MNOs) and over-the-top (OTT) service providers. MNOs and OTTs must receive customer "consent", in terms of the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act) and its Regulations, before sharing the customer's "personal information" with a third party. But MNOs have an additional requirement to meet, in terms of the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (RICA), which is not applicable to OTTs: a requirement whereby a customer must provide "written authorisation" to an MNO before the MNO can share "communication-related information which relates to the customer concerned" with a third party. In this article, I examine and analyse provisions of the POPI Act, POPI Act Regulations, RICA, other relevant legislation, court decisions, records of a Parliamentary hearing, the standard terms and conditions and privacy policies of two South African MNOs (Vodacom and MTN), and two international OTT service providers (Google and Facebook). Based on the analysis, I argue that the unequal regulatory treatment between the MNOs and OTTs, if allowed to persist, threatens to undermine the growth of key elements of South Africa's digital economy.

Keywords: data protection, South Africa, regulatory asymmetry, mobile network operators (MNOs), over-the-top (OTT) service providers, Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (RICA), Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act), digital economy, competition, personal information, privacy, consumer protection, compliance, enforcement, regulatory uncertainty

1. Introduction

The rise and rise of multinational content and communications service providers is evidence of the power of the digitally-enabled economy (Stoller, 2018). One feature of this digital economy is the erosion of mobile network operators' (MNOs') voice and SMS revenues due to their customers' increasing use of over-the-top (OTT) services such as WhatsApp (Facebook-owned), Google Hangouts, Skype (Microsoft-owned), and FaceTime (Apple-owned). These services are "over-the-top" in the sense that they operate via the internet, bypassing the MNOs' telecom platforms (BEREC, 2016). In South Africa, the two market-leading MNOs, Vodacom and MTN, have lobbied strongly, including at Parliament, for international OTT service providers to be regulated more heavily than they are at present, so as to make competition fairer between South African MNOs and the international OTTs (PMG, 2016).

When they were initially introduced, OTT services actually contributed to the bottom line of the MNOs. Customers used more mobile data when connecting to OTT services, and the MNOs were able to bill accordingly. But with mobile data becoming cheaper, this has led to reduced MNO data revenues, and when coupled with the decreased usage of traditional MNO SMS and voice services, this has begun to pose an increasing threat to the business models of the MNOs (see PMG, 2016; Stork et al., 2017). Accordingly, South Africa's MNOs are bundling OTT service offerings with their voice and SMS subscriber packages. The examples include the bundling of mobile money services, and zero-rated access to OTT web applications developed by the technology giants or their third-party associates (Stork, et al., 2017).

At the same time, South African MNOs are increasingly seeking to enter the realm of the digital economy that revolves around use of customer data, including use of customer personal information. For example, Vodacom's Vision 2020 strategy calls on it to develop deep insights about customer needs, wants, and behaviours, and to provide personalised service offerings, through the use of big data analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (Vodacom, 2017a, pp. 24, 28; 2018a; 2018b). A key Vodacom strategy is "[m]onetising mobile data" via its digital products and services (Vodacom 2017b, pp. 24-25). Vodacom aims to collaborate with third-party partners to deliver services relating to social media, music, gaming, and social data-sharing, supported by personalised offers. One such partnership is with Microsoft and its Azure cloud platform, allowing development, testing, management, and storing of mobile web apps (Microsoft, n.d.; Vodacom 2017b, p. 24).

To this end, in May 2018, Vodacom advertised the position of "Senior Specialist Information Security", an employee who would ensure that information security-related policies were drafted and reviewed periodically, and that Vodacom complied with local and international laws regarding information security and data privacy. On the same day, Vodacom advertised the position of "Senior Insights Manager", an employee who would research customers, profile them, and seek ways to monetise the findings (Vodacom, 2018c).

Competing MNO and OTT provider positions in Parliamentary hearings

Meanwhile, as they attempt to compete with international OTT service providers, South African MNOs contend with certain domestic regulatory requirements that the international OTT service providers do not face, including universal service and access regulations, tariff regulations, taxation, and-the focus of this article- heavier-touch regulation in respect of the sharing of customer data (PMG, 2016).

Leading South African MNOs Vodacom and MTN, made their objections to this apparently lighter-touch treatment of OTT service providers known in the 2016 hearing of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Telecommunications and Postal Services (PMG, 2016). They contended that OTT service providers were being granted an unfair advantage over legacy networks and services. They claimed the MNOs' regulatory burden was "excessive" and created competitive disadvantages for them compared to international OTT services (PMG, 2016). At the same 2016 Parliamentary hearing at which the South African MNOs complained of unfair treatment, representatives of international OTT service providers argued that MNOs and OTT service providers are in a symbiotic relationship, and that OTT service providers should not be burdened with the same "cumbersome" regulations that the South African MNOs carry. OTT service providers suggested that, instead, the "cumbersome and outdated regulation holding back the network operators" should be removed (PMG, 2016).

Stork, Esselaar, and Chair (2017) argue-broadly in line with one of the core arguments put forward by the international OTT service providers in the 2016 Parliamentary hearing-that although OTT services present a threat to domestic MNO voice and SMS revenues, they also present opportunities for the domestic MNOs (through, for example, zero-rating of OTT services) to gain market share. Other writers, meanwhile, share the MNOs' concern that MNOs are over-regulated in comparison to OTT service providers (Ganuza & Viecens, 2014; Jayakar & Park, 2014; Krämer & Wohlfarth, 2018; Peitz & Valletti, 2015; Sujata et al., 2015).

One of the complaints from the MNOs at the 2016 Parliamentary hearing was that OTT service providers sell on subscriber personal information that they collect while providing OTT services to South African MNO subscribers (PMG, 2016). However, international OTT service provider representatives at the hearing denied that they engaged in this practice. It is this matter-the treatment of customer personal data- that is at the heart of this article. Specifically, this article engages with the reality that, in the South African regulatory dispensation, domestic MNOs face more stringent requirements in their treatment of customer data than the requirements faced by the international OTTs.

Research outline

The focus of my research for this article was not on the full range of South African regulatory matters potentially affecting both MNOs and OTT service providers. Rather, my focus was on one regulatory element: the regulatory requirements regarding the treatment of customer data, and specifically the requirements that must be followed before an operator can share customer data with a third party.

My research focused on the data-sharing provisions of two South African statutes: the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication Related Information Act (RICA) of 2002 (hereafter "RICA", as amended by the Electronic Communications Act (ECA) of 2005 and the RICA Amendment Act of 2008); and the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act) of 2013 (hereafter "the POPI Act"). RICA has been in force since September 2005, while the POPI Act is not yet, at the time of finalising this article in June 2019, in force, and is expected to come into force in late 2019 or in 2020, with a 12-month grace period.

In addition to examining the provisions of these two South African Acts, I examined the POPI Act Regulations of 2018, other relevant South African laws, records from the proceedings of the aforementioned 2016 Parliamentary hearing on OTT regulation, the standard terms and conditions and privacy policies of two South African MNOs (Vodacom and MTN), and the standard terms and conditions and privacy policies of two international OTT service providers (Google and Facebook).

In the remainder of this article, I outline my findings from the above-listed primary documents, and I provide my argument, based on the findings, that: (1) there is clear regulatory asymmetry in South Africa, in respect of customer data protection regulation, between the treatment of domestic MNOs and international OTT service providers; and (2) this asymmetry potentially undermines the South African MNOs' ability to compete with OTT services and, more generally, to adapt to, and prosper in, fast-changing national and international digital economies. (At the same time, I am cognizant of, and in agreement with, arguments (see, for example, Krämer & Wohlfarth, 2018) that data protection regulation is necessary and that, when correctly calibrated, such regulation can be pro-competitive.

2. Data-sharing authorisation/consent provisions in RICA and the POPI Act RICA written authorisation requirement

In terms of South Africa's RICA of 2002 as amended, South African electronic communication service providers,1 including MNOs, are required to store "communication-related information" for law enforcement purposes (sects. 30(1)(b), 40(3)(b), 40(4)(a), 40(9), 40(10)). RICA defines communication-related information as:

[...] any information relating to an indirect communication which is available in the records of an electronic communication service provider, and includes switching, dialing or signalling information that identifies the origin, destination, termination, duration, and equipment used in respect, if each indirect communication generated or received by a customer or user of any equipment, facility or service provided by such an electronic communication service provider and, where applicable, the location of the user within the electronic communication system; [...] (RICA, sect. 1(1)).

In terms of RICA's sections 1, 39(1)(a), and 39(2), communication-related information includes internet protocol (IP) addresses; uniform resource locators (URLs); location information for mobile devices; international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) numbers (serial numbers of SIM cards); and international mobile equipment identity (IMEI) numbers (serial numbers on mobile devices) (see Shanapinda, 2016a; 2016b; Sutherland, 2017, p. 102). (A customer's communication-related information is hereafter referred to in this article as "RICA data").

Section 12 of RICA sets out restrictions on the sharing of RICA data:

Subject to this Act, no electronic communication service provider or employee of an electronic communication service provider may intentionally provide or attempt to provide any real-time or archived communication-related information to any person other than the customer of the electronic communication service provider concerned to whom such real-time or archived communication-related information relates. (RICA, sect. 12)

In section 14, RICA sets out an exception in terms of which RICA data can be shared with a third party:

Any electronic communication service provider may, upon the written authorisation given by his or her customer on each occasion, and subject to the conditions determined by the customer concerned, provide to any person specified by that customer, real-time or archived communication-related information which relates to the customer concerned. (RICA, sect. 14) (emphasis added)

In terms of RICA's written authorisation requirement, MNOs may not, without "written authorisation" from the customer, provide, or attempt to provide, any RICA data to any third party-except for provision to a law enforcement agency (sects. 12, 14, 42 and 43). In terms of section 14, the customer's written authorisation must be provided "on each occasion" of data-sharing, under "conditions determined by the customer", and in cases of sharing of information "which relates to the customer concerned." This RICA requirement that the customer provide written authorisation for third-party sharing of her or his RICA data is hereafter referred to in this article as the "RICA written authorisation requirement".

Of relevance to the matter of "written authorisation" are the provisions in sections 12 and 13(1) to 13(3) of South Africa's Electronic Communications and Transactions (ECT) Act of 2002. In terms of these provisions, an authorisation could be considered to be in writing, and signed, even if the written document or the written information is in the form of an electronic data message, such as an e-mail, provided that the information is accessible in a manner that is usable. Also of relevance is South Africa's Spring Forest Trading CC v Wilberry case of 2014, in which the Supreme Court of Appeal decided that e-mail communications can form legally binding agreements- when the contract is required to be in writing and the parties have agreed on the need for signatures but have not explicitly stated how the signatures must be executed. The implications of the ECT Act and the Spring Forest Trading CC v Wilberry decision are that customers of MNOs could potentially provide "written authorisation", via email, to have their data shared, without signing a hard-copy instruction. However, the standard terms and conditions of South African MNOs Vodacom and MTN, and their privacy policies, make no reference to this mode of obtaining a customer's written authorisation.

In the absence of written authorisation by the customer or a law enforcement requirement, RICA specifies that an electronic communication service provider (e.g., an MNO, for the purposes of this article) may not provide a customer's RICA data directly to any other entity apart from the customer. The "customer" is defined as:

[...] any person-

(a) to whom an electronic communication service provider provides an electronic communications service, including an employee of the electronic communication service provider or any person who receives or received such service as a gift, reward, favour, benefit or donation;

(b) who has entered into a contract with an electronic communication service provider for the provision of an electronic communications service, including a pre-paid electronic communications service; or

(c) where applicable-

(i) to whom an electronic communication service provider in the past has provided an electronic communications service; or

(ii) who has, in the past, entered into a contract with an electronic communication service provider for the provision of an electronic communications service, including a pre-paid electronic communications service;

[Definition of 'customer' substituted by s. 1 (b) of Act 48 of 2008.] (RICA, sect. 1(1))

These requirements in RICA do not apply to OTT service providers, because OTT service providers are not electronic communication service providers in terms of RICA and the ECA.

Meanwhile, there is convincing evidence that OTT service providers share the IP addresses, location information, IMSIs and IMEIs of South African customers with third parties (Binns et al., 2018; Dance, 2018; Facebook, 2018; Google, n.d.). During the aforementioned 2016 Parliamentary hearings, OTT service providers specified that they do not "sell" customer data to third parties. But the terms and conditions of Facebook and Google state that they "share" customer data, leaving unstated whether such sharing is in effect "selling". This lack of clarity is further complicated by the vagueness displayed by OTT service providers in respect of distinctions between what is personal data and what is anonymised data. Is it perhaps the case that personal data are not "sold" to third parties, while anonymised data are sold on? Is personal data anonymised and then "shared" but not "sold"? What precisely constitutes the "selling" of data? If a tech giant and a third party agree on a revenue-sharing arrangement, based on the development of a product reliant on the "exchange" of data (i.e., via use of neutral terms that do not specify "sale" of the data or that the data are "personal"), does that not still constitute sale of the data? My argument, for the purposes of this article, is that the data, whether arguably personal or not, is, in such exchanges, shared in a manner that results in a commercial arrangement, regardless of whether the data is directly or indirectly "sold"-because both parties benefit commercially in the end.

POPI Act consent requirement

The POPI Act of 2013, which is expected to come into force in late 2019 or 2020, aims, among other things, to level the competitive playing field in respect of data protection regulation in South Africa. Both the domestic MNOs and international OTTs will equally be subject to the provisions of the POPI Act when it comes into force. The Act states that two of its purposes are as follows:

(a) give effect to the constitutional right to privacy, by safeguarding personal information when processed by a responsible party, subject to justifiable limitations that are aimed at-

(i) balancing the right to privacy against other rights, particularly the right of access to information; and

(ii) protecting important interests, including the free flow of information within the Republic and across international borders;

(b) regulate the manner in which personal information may be processed, by establishing conditions, in harmony with international standards, that prescribe the minimum threshold requirements for the lawful processing of personal information; [...] (POPI Act, sect. 2(a)-(b))

The Preamble to the POPI Act states that it regulates the flow of information:

[...] consonant with the constitutional values of democracy and openness, the need for economic and social progress, within the framework of the information society, requires the removal of unnecessary impediments to the free flow of information, including personal information; [.] (POPI Act, Preamble)

Under the POPI Act, MNOs and OTT service providers are considered "responsible parties" in respect of their processing of "personal information", and "personal information" may only be collected and shared by "responsible parties" when "[...] necessary for pursuing the legitimate interests of the responsible party or of a third party to whom the information is supplied" (POPI Act, sect. 11(1)(f)).

A key test under the POPI Act in respect of sharing customer data-a test that must be applied by both MNOs and OTTs-is whether or not any given set of customer data constitutes "personal information" in terms of the Act. Only data that does not constitute "personal information" in terms of the Act can be "processed" without customer "consent" (with "processing" being a set of activities that includes "dissemination"). Sect. 1 of the POPI Act defines "personal information" as:

[...] information relating to an identifiable, living, natural person, and where it is applicable, an identifiable, existing juristic person, including, but not limited to-

(a) information relating to the race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, national, ethnic or social

origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, physical or mental health, well-being, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth of the person;

(b) information relating to the education or the medical, financial, criminal or employment history of the person;

(c) any identifying number, symbol, e-mail address, physical address, telephone number, location information, online identifier or other particular assignment to the person;

(d) the biometric information of the person;

(e) the personal opinions, views or preferences of the person;

(f) correspondence sent by the person that is implicitly or explicitly of a private or confidential nature or further correspondence that would reveal the contents of the original correspondence;

(g) the views or opinions of another individual about the person; and

(h) the name of the person if it appears with other personal information relating to the person or if the disclosure of the name itself would reveal information about the person; [...] (POPI Act, sect. 1)

As stated above, the Act prohibits the "processing", without customer "consent", of "personal information", with "processing" defined as:

[.] any operation or activity or any set of operations, whether or not by automatic means, concerning personal information, including-

(a) the collection, receipt, recording, organisation, collation, storage, updating or modification, retrieval, alteration, consultation or use;

(b) dissemination by means of transmission, distribution or making available in any other form; or

(c) merging, linking, as well as restriction, degradation, erasure or destruction of information; [.]. (POPI Act, sect. 1)

However, section 6 of the POPI Act states:

6. (1) This Act does not apply to the processing of personal information- [.]

(b) that has been de-identified to the extent that it cannot be re-identified again; [.]. (POPI Act, sect. 6(1)(b))

The effect of section 6(1)(b) is that "personal information" is no longer treated by the Act as "personal information" if it has been anonymised ("de-identified"). Thus, no consent is required to engage in "processing", including sharing, of such data. The "consent" that is required for sharing of "personal information" is defined in section 1 as:

[...] any voluntary, specific and informed expression of will in terms of which permission is given for the processing of personal information. (POPI Act, sect. 1)

This POPI Act requirement is hereafter referred to as the "POPI Act consent requirement".

Section 69 of the POPI Act deals with one specific type of data-sharing with third parties: processing for the purposes of "[d]irect marketing by means of unsolicited electronic communications". In terms of section 69(1), MNOs and OTT service providers, as "responsible parties" , must obtain the consent of the individual customer to collect and share the customer's personal information for direct marketing purposes by means of electronic communications such as email and when automated decisions are made about the individual:

69.(1) The processing of personal information of a data subject for the purpose of direct marketing by means of any form of electronic communication, including automatic calling machines, facsimile machines, SMSs or e-mail is prohibited unless the data subject-

(a) has given his, her or its consent to the processing; or

(b) is, subject to subsection (3), a customer of the responsible party.

In respect of data processing for direct marketing, the POPI Act Regulations of 2018 specify that a data subject (i.e., a customer) must provide "written" consent, via a form ("Form 4") provided in the Regulations, for processing of personal data for direct marketing. But instances of sharing of data with third parties for purposes other than direct marketing, the Regulations do not specify the form that the consent must take.

Regulatory asymmetry

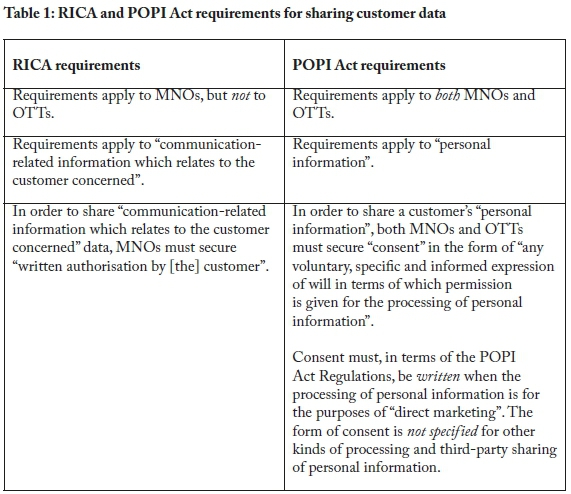

Table 1 summarises the contrasting requirements, under RICA and the POPI Act respectively, in respect of operators' sharing of customer data with third parties.

Under the POPI Act consent requirement, MNOs and OTT service providers have the same obligations. Meanwhile, MNOs are, at the same time, required to also comply with the RICA written authorisation requirement. Thus, when the POPI Act comes into force, MNOs will be required to comply with two tests, the RICA test and the POPI Act test, when sharing customer data with third parties. When the POPI Act comes into force, MNOs will be required to continue to obtain customer written authorisation in terms of RICA and to start to obtain customer consent in terms of the POPI Act. OTT service providers, meanwhile, will only need to start to comply with the POPI Act consent requirement. There is clear regulatory asymmetry here.

There is also the potentially significant difference, as seen in Table 1, between the two Acts' wordings in respect of what customer information is being dealt with, i.e., the potential difference between the phrases "communication-related information that relates to the customer concerned" and "personal information". Under RICA, the scope of customer data is apparently broad, covering many types of communication-related data-whether potentially personal information or not-as long as the data is "communication-related" and also "relates to the customer concerned". This is arguably a significantly higher hurdle to jump than the hurdle presented by the narrower "personal information" specification under the POPI Act. In other words, the MNOs are likely, in terms of RICA, to need to obtain authorisation for data-sharing with third parties in a broader range of cases than the cases in which OTTs and MNOs will be required to obtain consent in terms of the POPI Act.

The legal meaning of the POPI Act's "consent" and "personal information" provisions will almost certainly require interpretation by the courts, along with RICA's "written authorisation" and "communication-related information which relates to the customer concerned" provisions. And these provisions may also need to be legally interpreted in relation to each other, e.g., a judicial ruling is likely to be necessary to decide the extent to which the term "communication-related information that relates to the customer concerned" under RICA equates to "personal information" under the POPI Act. Where it is determined that the information to be shared with a third party does relate to the customer (in terms of RICA), the MNO would apparently be bound to obtain written authorisation from the customer. And where the same information is determined to be personal (in terms of the POPI Act), the MNO would apparently need to also obtain the consent of the customer-with that consent needing to be in writing if the data is to be used for direct marketing.

The OTTs must comply with one act, while the MNOs must comply with two, and, as demonstrated above, there is every reason to believe that the compliance realities will be different between the two Acts (see also Mayer et al., 2016; Shanapinda, 2016a; 2016b). This higher compliance threshold for MNOs than for OTT providers is clearly to the benefit of the OTTs. There will be, in effect, two "tests" at play here, outlined in two separate but complementary pieces of law, and it would seem to be inevitable that the two tests will, in many instances, produce two different outcomes-and therein lies the South African regulatory asymmetry between the treatment of MNOs and OTT service providers in respect of sharing of customer data with third parties.

Enforcement of the RICA and POPI Act provisions

It is also important to note that RICA does not provide for oversight to ensure that the written authorisation requirement is complied with prior to an operator sharing RICA data with a third party. Moreover, there is no enforcement mechanism in cases where data-sharing with a third party occurs without the required written authorisation (RICA, sect. 50(2)). This leaves customer privacy poorly protected under RICA. The POPI Act creates a body called the Information Regulator, mandated to educate on, monitor, and enforce compliance (sects. 39, 40). The Information Regulator will have the power to impose fines or imprisonment (sects. 107 and 109). Thus, in the future, when the POPI Act is in force, the Information Regulator will monitor and enforce POPI Act compliance equally for both MNOs and OTT service providers.

3. MNO and OTT data-sharing policies and practices

I found, through my primary document analysis, that the privacy policies and standard terms and conditions, of the leading South African MNOs (Vodacom, MTN), and of the leading OTT service providers (Facebook, Google), were materially similar. They all claim to obtain the consent of the customer before sharing customer data with third parties to, for instance,research, develop and deliver existing or new digital products and services (Facebook,n.d.; Google,n.d.; MTN,n.d.; Vodacom,n.d.a).The MNOs appear to have adopted similar terms and conditions to those of the OTT service providers. And a key similarity I was able to identify-a key similarity for the purposes of the focus of my research-was that the privacy policies of both the MNOs and the OTT service providers lacked any reference to a written authorisation requirement.

Google shares customer data with third parties, e.g., third parties identify and track user devices in the Google Play store's mobile ecosystem. The nature of the business of identifying, tracking, and sharing data about users and their devices is a transnational business (Binns, et al., 2018; Dance, 2018). The Vodacom and MTN privacy policies, as with the Facebook and Google policies, state that the operators disclose customer information to third parties. But the policies do not specify whether or not this information is disclosed based only on conditions set by the customer, and only to third parties specified by the customer-i.e, the practices required by the RICA written authorisation requirement (Vodacom, n.d.a; n.d.b; n.d.c; MTN, n.d.; Facebook; n.d.; Google, n.d.). Thus, it would appear that the RICA written authorisation requirement is not being fully met by existing MNO standard terms and conditions and privacy policies. This apparent lack of compliance with the RICA written authorisation requirement contradicts RICA's apparent anticipation of a scenario whereby there is a form of dialogue and consultation between customers and South African communication service providers, i.e., a situation where customers know their rights and are in a position to influence the terms of how their RICA data are shared, as opposed to having the terms dictated by the MNOs.

It was also noted above that RICA does not provide for any oversight or enforcement of its written authorisation requirement. According to the OTT service providers, South African customers could rely on protection under their local laws and court systems if seeking to challenge whether an OTT's data-sharing behaviour obeyed local laws (Facebook; n.d.; Google, n.d.). But in respect of OTT data-sharing behaviour, since only RICA (and not the POPI Act) is currently in effect-and since the RICA written authorisation requirement does not regulate OTT service providers-there is at present no clear legal protection for the South African customer in respect of sharing of its MNO data with third parties. Since the OTT service providers are not required to comply with the RICA written authorisation requirement, the standard terms and conditions of the OTT service providers would be difficult to challenge. The privacy policies of the OTT service providers are therefore essentially unregulated and unchecked at present in South Africa, allowing the OTT service providers to participate in third party data-sharing arrangements without any limits.

The longer the commencement of the POPI Act is delayed, the longer the OTTs' practices become entrenched and increasingly difficult to review. At present, and up until the POPI Act takes effect, the OTT service providers can be regarded as self-regulatory in respect of how they treat the data they collect from South African customers. And the OTT service providers can, on their own initiative, update their terms and conditions at any time (Facebook, n.d.; Google, n.d.).

An example of OTT service providers' resistance to the regulation of their data-handling practices was provided by Facebook's transfer of customer data out of Ireland in April 2018, in order to avoid having the data fall under the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force on 25 May 2018 (Hern, 2018).

4. RICA, the POPI Act, and regulation of the digital economy

RICA and the POPI Act outline legal requirements, and limitations, in respect of privacy, data protection, and data access for law enforcement. These laws seek to encourage competitive participation in the digital economy and, at the same time, to set restrictions on such participation.

The RICA written authorisation requirement imposes data protection regulations directly on private and public entities, thus potentially modifying, indirectly, the economic behaviour of these businesses. The aim is to ensure that digital services are created and delivered in a secure environment that respects privacy and allows legitimate businesses to function effectively and profitably. The RICA written authorisation requirement is a measure that potentially, indirectly, influences the economic behaviour of South African MNOs, potentially helping to achieve the public interest aims of: customer control over use of personal data; and the prevention of misuse of customer personal data.

As discussed above, it would appear that South African MNOs are at present not fully compliant with the RICA written authorisation requirement. It would appear that they are deploying digital products and services using RICA data and sharing the data with third parties, seeking to realise forward-looking digital economy strategies-with, it would seem, little regard for the RICA regulatory requirements, and/or with an absence of good faith effort towards ensuring minimal or material compliance. This may be because the compliance burden is too heavy to bear, or it may be a calculated business decision by MNOs to not comply and deal with allegations of non-compliance if and when they arise. Not moving ahead with digital strategies grounded in the sharing of customer data may be seen by MNOs as a business imperative, with, accordingly, the risks of RICA non-compliance seen as negligible given the absence, in RICA, of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. At present, it seems fair to say that RICA is allowing MNOs to use RICA data, originally collected for possible sharing for law enforcement purposes, for commercial purposes. The non-enforcement of the RICA written authorisation requirement appears to be allowing the MNOs to share the data about their customers with third parties, in an effort to more fully participate in the digital economy, without fear of penalties for misuse of the RICA data.

5. Potential future impacts of the asymmetric RICA written authorisation requirement

As long as RICA's written authorisation requirement remains in place for the sharing of customer data with third parties, there are several possible scenarios that could emerge-all potentially impacting the digital services ecosystem-and they are not mutually exclusive.

Continued MNO non-compliance

Not complying with the RICA written authorisation requirement enables MNOs to more realistically consider: developing their own OTT services; entering into partnerships with OTTs to deliver OTT services; entering into data-processing mergers and acquisitions; and commercially sharing RICA data with third parties able to process the data to research and develop innovative products and services. Non-compliance provides the MNOs with enhanced opportunities to diversify their businesses in the mobile ecosystem, to advance their participation in digital services and the digital economy, and to enter into revenue-sharing arrangements.

Consumer activism and corporate citizenship requirements

Despite the absence, in RICA, of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms for the written authorisation requirement, MNO non-compliance could nevertheless subject the MNOs to potential legal risks. A consumer association or privacy protection organisation could legally challenge MNOs under South Africa's Consumer Protection Act (CPA) of 2008. Under the CPA, the customer has the right to fair, just, and reasonable terms and conditions (sects. 48-52), and the customer is protected against improper trade practices and deceptive, misleading, unfair, or fraudulent conduct (sect. 3(1)(d)). Under the CPA, MNOs must act responsibly and inform customers of their rights (CPA, sect. 3(1)(a), (c)-(f)). The privacy policies and standard terms and conditions of the MNOs, in omitting references to the RICA written authorisation requirement, could be questionable in terms of the CPA. Consumer rights in this area could be enforced by the National Consumer Tribunal if complaints against the MNOs were to be lodged with the Tribunal (CPA, sects. 69, 71).

Additionally, under South Africa's King IV Code, in terms of which South African companies must act ethically and establish ethics committees, MNOs should in fact incorporate the RICA written authorisation requirement in their privacy policies, standard terms and conditions, and risk assessment and management policies (PwC, 2017, p. 30).

MNO compliance

Complying with the RICA written authorisation requirement would likely be extremely burdensome, both operationally and financially, for South African MNOs. Compliance could negatively impact MNOs' efforts to more fully partake in the digital economy, while OTT service providers would be able to continue to operationalise their data-sharing arrangements with complete freedom (until the POPI Act comes into force, and with relative freedom even under the POPI Act).

Increased MNO take-up of zero-rated OTT services

According to Stork et al. (2017) and Feasey (2015), South African MNOs may adopt the strategy of increasingly bundling zero-rated products from OTT service providers into their MNO offerings. Vodacom followed this approach by bundling a zero-rated music-streaming OTT offering into its packages-but found, however, that it was not able to effectively compete in the digital content space because of a lack of access to content at reasonable rates (Vodacom, 2017b, p. 23). This may have contributed to Vodacom's adoption of its aforementioned Vision 2020 push to more aggressively seek a leading place in the digital content ecosystem.

Regulatory uncertainty

Under the CPA, MNOs face regulatory uncertainty, as informed customers may rebel and lobby for regulatory action to protect their privacy and data usage rights. OTT service providers, meanwhile, have minimal concerns of this nature, as they are not subject to the RICA written authorisation requirement that makes MNOs vulnerable under the CPA. MNOs need regulatory certainty, just as OTT service providers do, in order to fully partake in the digital economy, i.e., in order to partake without fearing unpredictable regulatory interventions that affect their digital economy strategies.

6. Conclusion

As this study has shown, RICA's written authorisation requirement, which requires MNOs but not OTT service providers to get customer written authorisation before sharing data with third parties, creates a regulatory asymmetry. This asymmetry imposes an unfair regulatory burden on the MNOs as they face competition from OTT service providers and, more generally, seek to grow digital businesses not reliant on traditional voice and SMS offerings.

The MNOs appear, at present, to be disregarding the RICA written authorisation requirement-a course ofaction made possible by the absence, in RICA, of monitoring or enforcement mechanisms for the requirement, and by the absence, to date, of consumer complaints raised and submitted to the National Consumer Tribunal. The privacy policies of South Africa's two market-leading MNOs, Vodacom and MTN, do not make any reference to the RICA written authorisation requirement.

MNOs appear to be left with a dilemma, whereby they must choose either (1) to continue to disregard the RICA written authorisation requirement, and risk sanction, so as to push aggressively forward with digital propositions reliant on the sharing of customer data with third parties; or (2) to seek to comply with the RICA written authorisation requirement, so as to avoid the risk of sanction, and, accordingly, be less aggressive in the pursuit of new digital business models based on customer data-sharing.

Based on the findings and analysis produced by this study, it seems clear that the RICA written authorisation requirement needs to be harmonised with the POPI Act's lighter-touch consent requirement. Such harmonisation would: (1) reduce the severity of RICA's current asymmetric burden on MNOs in respect of the customer consent threshold for third-party-sharing of customer data; and (2) allow for the elimination of the asymmetry entirely when the POPI Act's consent requirement, which applies equally to both MNOs and OTT service providers, comes into effect in the near future. Once the POPI Act comes into force, consideration could then be given to removing the customer authorisation requirement entirely from RICA and making customer authorisation under RICA subject to the provisions of the POPI Act.

Acknowledgement

This article draws on content from the author's presentation at the 4th Annual Competition and Economic Regulation (ACER) Week Southern Africa conference in Johannesburg, 16-20 July 2018 (Shanapinda, 2018).

References

South African Acts and Regulations

Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008.

Electronic Communications and Transactions (ECT) Act 25 of 2002.

Electronic Communications Act (ECA) 36 of 2005.

Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act) 4 of 2013.

Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication Related Information Act (RICA) 70 of 2002.

Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication Related Information Amendment Act (RICA Amendment Act) 48 of 2008.

Information Regulator: Protection of Personal Information Act, 2013 (Act No. 4 of 2013): Regulations Relating to the Protection of Personal Information, 2018. Government Gazette, No. 42110, No. R. 1383, 14 December.

Other Sources

Binns, R., Lyngs, U., Van Kleek, M., Zhao, J., Libert, T., & Shadbolt, N. (2018). Third party tracking in the mobile ecosystem. In WebSci '18: 10th ACM Conference on Web Science, May 27-30, Amsterdam. New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3201064.3201089

Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC). (2016). Report on OTT services. Retrieved from https://berec.europa.eu/eng/documentregister/subjectmatter/berec/reports/5751-berec-report-on-ott-services

Dance G. J. X., Confessore N., & LaForgia, M. (2018, June 3). Facebook gave device makers deep access to data on users and friends. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/03/technology/facebook-device-partners-users-friends-data.html

European Union (EU). (2016). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016/679 (implementation date: 25 May 2018).

Feasey, R. (2015). Confusion, denial and anger: The response of the telecommunications industry to the challenge of the Internet. Telecommunications Policy, 39(6), 444-449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2014.08.007 [ Links ]

Facebook. (n.d.). Terms of service. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms/update

Ganuza, J. J., & Viecens, M. F. (2014). Over-the-top (OTT) content: Implications and best response strategies of traditional telecom operators. Evidence from Latin America. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 16(5), 59-69. https://doi.org/10.1108/info-05-2014-0022 [ Links ]

Google. (n.d.). Google privacy policy. Retrieved from https://policies.google.com/privacy

Hern, A. (2018, April 19). Facebook moves 1.5bn users out of reach of new European privacy law. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/apr/19/facebook-moves-15bn-users-out-of-reach-of-new-european-privacy-law

Jayakar, K., & Park, E.-A. (2014). Emerging frameworks for regulation of over-the-top services on mobile networks: An international comparison. Paper presented to TPRC Conference, 31 March. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2418792

Krämer, J., & Wohlfarth, M. (2018). Market power, regulatory convergence, and the role of data in digital markets. Telecommunications Policy, 42(2), 154-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2017.10.004 [ Links ]

Mayer, J., Mutchler, P., & Mitchell, J. C (2016). Evaluating the privacy properties of telephone metadata. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(20), 5536-5541. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1508081113 [ Links ]

Microsoft. (n.d.). Microsoft Azure. Retrieved from https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/services/app-service/

MTN (n.d.). Terms and conditions. Retrieved from https://www.mtn.co.za/Pages/Termsandconditions.aspx?pageID=26

Peitz, M., & Valletti,T. (2015). Reassessing competition concerns in electronic communications markets. Telecommunications Policy, 39(10), 896-912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2015.07.012 [ Links ]

Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMG). (2016) Over-the-Top (OTT) policy and regulatory options Meeting Summary. 26 January. Cape Town: Portfolio Committee on Telecommunications and Postal Services, Parliament of South Africa. Retrieved from https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/21942/

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2017). Governing structures and delegation - A comparison between King IV TM and King III. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/king-iv-comparison.pdf

Privacy Commissioner v Telstra Corporation Limited [2017] FCAFC 4

Shanapinda, S. (2016a). Retention and disclosure of location information and location identifiers. Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, 4(4), 251279. https://doi.org/10.18080/ajtde.v4n4.68 [ Links ]

Shanapinda, S. (2016b). The types of telecommunications device identification and location approximation metadata: Under Australia's warrantless mandatory metadata retention and disclosure laws. Communications Law Bulletin, 35(3), 17-19. [ Links ]

Shanapinda, S. (2018). OTT wars in South Africa: The privacy and cybersecurity regulatory asymmetry and how it complicates advancing the digital economy fairly - a theoretical perspective. Presentation to the 4th Annual Competition and Economic Regulation (ACER) week Southern Africa conference in Johannesburg, 16-20 July. Retrieved from https://www.competition.org.za/acer-conference-papers

Spring Forest Trading 599 CC v Wilberry (Pty) Ltd t/a Ecowash and Another (725/13) [2014] ZASCA 178; 2015 (2) SA 118 (SCA) (21 November 2014). Retrieved from http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZASCA/2014/178.pdf

Stoller, K. (2018, June 6). The world's largest tech companies 2018: Apple, Samsung take top spots again. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinstoller/201nu898/06/06/worlds-largest-tech-companies-2018-global-2000/#6354683c4de6

Stork, C., Esselaar, S., & Chair, C., (2017). OTT - threat or opportunity for African MNOs? Telecommunications Policy, 41(7-8), 600-616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2017.05.007 [ Links ]

Sujata, J., Sohag, S., Tanu, D., Chintan, D., Shubham, P., & Sumit, G. (2015). Impact of over the top (OTT) services on telecom service providers. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 8(S4), 145-160. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2015/v8iS4/62238 [ Links ]

Sutherland, E. (2017). Governance of cybersecurity - the case of South Africa. The African Journal of Information and Communication (AJIC), 20, 83-112. https://doi.org/10.23962/10539/23574 [ Links ]

Telstra Corporation Limited and Privacy Commissioner [2015] AATA 991 (18 December 2015) Vodacom. (2017a). Best technology. Retrieved from http://www.vodacom-reports.co.za/integrated-reports/ir-2017/best-technology.php

Vodacom. (2017b). Vodacom Group Limited integrated report for the year ended 31 March 2017. Retrieved from http://www.vodacom-reports.co.za/integrated-reports/ir-2017/pdf/full-integrated-hires.pdf

Vodacom. (2018a, April 18). Vodacom accelerates digital transformation with first-to-market launch of suite of Azure solutions. Press release. Retrieved from http://www.vodacom.com/news-article.php?articleID=4472

Vodacom. (2018b, May 10). Vodacom puts its partners in the driving seat of digital transformation. Press release. Retrieved from http://www.vodacom.com/news-article.php?articleID=4476

Vodacom (2018c). Senior specialist information security. Job advertisement. LinkedIn. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/jobs/view/686527109

Vodacom (2018d). Senior insights manager. Job advertisement. LinkedIn.

Vodacom. (n.d.a). Privacy policy. Retrieved from http://www.vodacom.co.za/vodacom/terms/privacy-policy

Vodacom. (n.d.b). Vodacom app store terms and conditions. Retrieved from https://myvodacom.secure.vodacom.co.za/vodacom/terms/vodacom-app-store-terms-and-conditions

Vodacom. (n.d.c). Groups. Retrieved from https://www.vodacombusiness.co.za/cs/groups/public/documents/document/azure-brochure.pdf

1 RICA's references, in the original 2002 Act, to ''telecommunication service provider'', "telecommunication service", and "telecommunication system", were amended, respectively, to ''electronic communication service provider'', "electronic communication service", and "electronic communication system", by section 97 of the Electronic Communications Act (ECA) 36 of 2005.