Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The African Journal of Information and Communication

On-line version ISSN 2077-7213

Print version ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.22 Johannesburg 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/10539/26173

ARTICLE

Evolution of Africa's Intellectual Property Treaty Ratification Landscape

Jeremy de BeerI; Jeremiah BaarbéII; Caroline B. NcubeIII

IProfessor, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa; and Senior Research Associate, Intellectual Property Unit, University of Cape Town

IIFellow, New and Emerging Researchers Group, Open African Innovation Research (Open AIR) network, University of Ottawa

IIIProfessor, Department of Commercial Law, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Intellectual property (IP) policy is an important contributor to economic growth and human development. However, international commitments harmonised in IP treaties often exist in tension with local needs for flexibility. This article tracks the adoption of IP treaties in Africa over a 131-year span, from 1884 to 2015, through breaking it down into four periods demarcated by points in time coinciding with key events in African and international IP law: the periods 1884-1935, 1936-1965, 1966-1995, and 1996-2015. The article explores relevant historical and legal aspects of each of these four periods, in order to assess and contextualise the evolutions of the IP treaty landscape on the continent. The findings show that treaties now saturate the IP policy space throughout the continent, limiting the ability to locally tailor approaches to knowledge governance.

Keywords: international law, Africa, intellectual property (IP), treaty ratification, development, data visualisation, WIPO, WTO, trade, harmonisation

1. Introduction

Innovation policy is important for economic growth and human development (Muchie, 2016, p. 26). Countries across Africa are, therefore, developing policy to encourage innovation (Adesida, Karuri-Sebina & Resende-Santos, 2016). Measures that address intellectual property (IP) in a locally relevant way are integral to the broader innovation landscape.

IP policy is complex and controversial because it seeks to balance protection of, and access to, knowledge. Policy that leads to either an absence, or overabundance, of proprietary IP rights may discourage innovation (Heller & Eisenberg, 1998, p. 698). Domestic policymakers may look to research showing that strict IP protection economically advantages developed countries while disadvantaging developing countries (Forero-Pineda, 2006; Schneider, 2005). Similarly, they may be presented with research supporting a contrary view (Gathii, 2016). Evidence-based IP policymaking is, therefore, often a fraught exercise (De Beer, 2016).

The international dimensions of IP are as complex, and often in fact more complex, than domestic aspects. Because IP protects valuable intangibles, these resources move easily across borders. Accordingly, international treaties set out minimum standards for IP protections. There is tension between international harmonisation (on the belief that it promotes predictability and, thus, foreign direct investment and international trade) versus national flexibility (to eliminate trade barriers, and to ensure national governments are able to develop policies that respond to local needs).

National governments on the African continent are increasingly constrained by international IP law when seeking to tailor their approaches to localised knowledge governance priorities. At the same time, there have in recent years been significant continental and regional developments in Africa with respect to IP norm-setting (Ncube, 2016). Meanwhile, the confluence of IP policy with trade policy has generated an additional layer of complexity to the already-wide array of international negotiations (De Beer, 2013).

There is research evidence showing that the pressures exerted by the international harmonisation agenda has resulted in "IP socialisation", resulting in ostensibly context-inappropriate IP norms frequently being adopted in developing countries (Morin, Daley, & Gold, 2011). Research is also emerging that generates recommendations of appropriate strategic directions for African policymakers to take in pursuit of African-context-appropriate IP norms and deeper continent-wide economic integration (Ncube, Schonwetter, De Beer & Oguamanam, 2017). The ability to implement such recommendations is, however, constrained to some extent by the powerful global IP governance schemata.

In this article, we describe the results of a study in which we mapped a 130-year history of influence by the international IP treaty landscape on governance of, protection of, and access to, knowledge in Africa. We begin by describing our data collection and visualisation methods, used to interrogate the history and extent of African countries' binding to the global IP regime.

Our findings and analysis are organised into four distinct periods of treaty-making history. The demarcations from one period to another are not bright lines reflecting sudden transformations. Rather, we identified these broad and general phases in the proliferation of IP treaties in Africa by combining quantitative insights from our dataset together with multi-disciplinary literature on the political and economic development of Africa during the modern era of multilateral IP norm-making.

With respect to the period 1885 and 1935, we describe how IP treaties were instruments of colonialism. Between 1936 and 1965, we observe how treaties were maintained in a neo-colonial response to independence. Then, we find the period from 1966 to 1995 characterised by attempts to limit the influence of African countries on global IP policy. Finally, in the "African rising" phase from 1996 to 2015, we see increasing focus on innovation policy as the frame within which African national, regional and continental IP policies must sit.

2. Methods

We engaged in four overlapping activities for our data collection, analysis and presentation:

-

identification of international IP treaties;

-

gathering, processing and validating of treaty data and treaty ratification data;

-

development of an interactive map showing ratifications; and

-

quantitative and qualitative data analysis. 1

Identification of international IP treaties

We began by identifying relevant international treaties and agreements. A review of WIPO's website and other resources (Frankel & Gervais, 2016; UNECA, 2016; WIPO, n.d.) provided a list of 34 instruments that met the following criteria for inclusion:

-

the instrument is multilateral;

-

the list of parties to the instrument includes at least one African country; and

-

the instrument binds signatories to take measures in respect of:

o copyrights;

o patents;

o trademarks;

o trade secrets;

o traditional knowledge;

o bio-diversity; and/or

o genetic resources.

We did not include multilateral trade agreements or economic partnerships, apart from the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS), which is Annex 1C of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation (WTO). While other trade and economic partnership agreements and partnerships are highly relevant to the international IP landscape governing knowledge in Africa, mapping their proliferation and analysing their implications would require different methods and data sources. That work remains to be done.

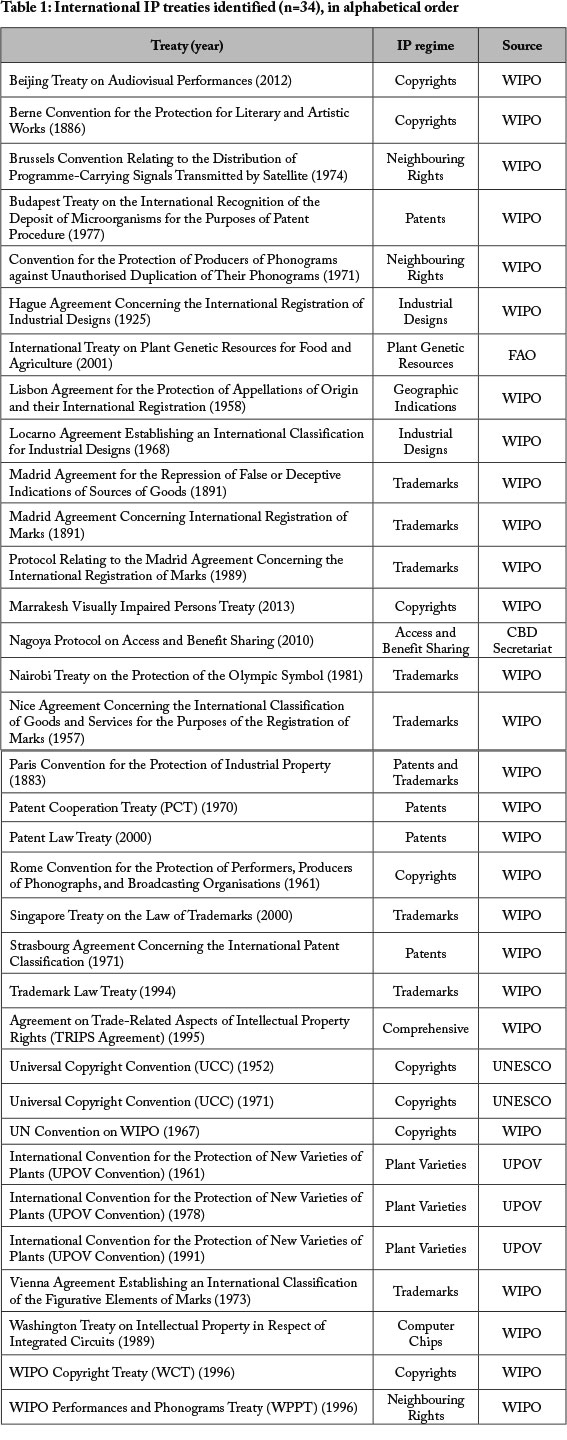

The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) administers 26 treaties, all of which met the criteria for inclusion in the study, listed among the items in Table 1 below (WIPO, n.d.). WIPO curates records of four additional treaties by making them available on its WIPO Lex database: TRIPS (pursuant to a cooperation agreement between WIPO and the WTO), the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources, and the Universal Copyright Convention (UCC), which are also included in Table 1. The Beijing Treaty on Audiovisual Performances, and the Washington Treaty on Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits, are not yet in force, and therefore excluded from our analysis.

We accessed information pertaining to the other three agreements in Table 1- the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (IT PGRFA), and the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV)-on their respective websites (CBD, n.d., IT PGRFA, n.d., UPOV, n.d.). Only publicly available records, published online, were used in this study. These agreements are not all dedicated "IP" instruments in the sense that the WIPO-administered treaties and the TRIPS Agreement are. Rather, they contain provisions that are pertinent to IP protection and have been included in this study due to their significance.

Gathering, processing and validating treaty and treaty ratification data

Treaties administered by WIPO include a "Contracting Parties" section containing a table listing parties to the treaty, as well as the date of signature, filling of legal instrument used to ratify the treaty, and entry into force, amongst other details. Similar tables were available for the Nagoya Protocol, which is administered by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources, administered through the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). From these online tables we scraped the raw data for each treaty and their accompanying acts into an Excel database. Data from each treaty and act were deposited in a separate sheet in the database. Because tables were not available online for the three UPOV treaties (1961, 1978, 1991), we constructed the data manually from the list of convention notifications.

In summary, we were able to gather data on:

-

ratifications of 34 IP treaties

-

IP ratification behaviour in respect of the 34 treaties by 54 African countries over a 131-year period, from 1884 to 2015

-

a total of 485 ratifications by the 54 countries

We then cleaned and processed the data. After ensuring all entries were represented in machine-readable formats, we began by identifying and isolating the entries for African countries and then compiled the data into a series of aggregated tables for use in the study. Because WIPO reports which of its Member States have acceded to, or ratified, the treaties that it administers, only those states listed by WIPO or other administering organisations were included in the study. We loaded a polished, user-friendly version of the database, entitled "Status of IP Treaties in Africa", to Airtable. com, a cloud database provider, so that the database can be used as an open source resource by other researchers and the general public (Baarbé & De Beer, 2016).

Development of interactive map showing ratifications

In order to visualise African countries' ratification of international IP treaties in temporal and spatial terms, we developed an interactive web map application (Baarbé, 2016; baarbeh, n.d.). The application superimposes a vector circle over each African country, representing the number of treaties ratified by that country. The larger the circle, the greater number of treaties the country has ratified. A slider changes the display in five-year increments ranging from 1885 to 2015, allowing users to view the history of IP treaty ratification across a 130-year period. We used JavaScript, the Leaflet.js data-mapping library, and Mapbox to develop the web application (Leaflet, n.d.; Mapbox.com, n.d.). We sourced latitudinal and longitudinal data from Google's Open Dataset Canonical Concepts repository (Google Developers, n.d.). The application is based on Donohue, Sack and Roth's time-series mapping tutorial (Donohue, Sack & Roth, 2013).

Quantitative and qualitative analysis

Quantitatively, the extracted descriptive statistics showed the status of treaty ratifications across the continent, identifying which national IP contexts were offering more or fewer opportunities for localised IP policy innovation. (MS Excel was used to calculate common statistical descriptors.) Qualitatively, the interactive map revealed the 130-year history of IP treaty adoption in Africa, providing contrasts between colonial/neo-colonial legacies of the international IP system and more recent, post-colonial attempts to engender developmental approaches to knowledge governance.

This research also potentially lays the groundwork for future analyses using inferential statistics to investigate longitudinal relationships between IP treaty adoption and metrics such as the Human Development Index, the Global Innovation Index, and national gross domestic product (GDP).

3. Findings and discussion

Ratifications between 1884 and 2015

As explained above our database tracks the years-beginning in 1884, when Tunisia ratified the Paris Agreement-on which 54 African countries ratified 34 international IP treaties across a 131-year time span, up to the end of 2015. During this time, the total number of ratifications grew to 485. Table 2 shows the evolution of the ratifications in tabular form, with cumulative African ratification totals at four moments in time:

-

1935

-

1965

-

1995

-

2015

Ratification dates were used because they represent the date on which legal obligations take effect. For TRIPS, because countries did not have to ratify it, its in-force date of 1995 was used as a measure of legal obligation on a country. Although TRIPS came into force in 1995, a series of transition periods in the Agreement exempted some countries from complying with its provisions. For instance, Article 66.1 gave least developed countries (LDCs) a 10-year compliance transition period, starting 1 January 1996, which exempted them from compliance with TRIPS provisions except for Article 3 (national treatment), Article 4 (most-favoured-nation (MFN) treatment), and Article 5 (precedence of WIPO procedures). This transition period was later extended for a further seven and a half years (until 1 July 2013), and thereafter for a further eight years (until 1 July 2021, or earlier should the LDC become a developing country).

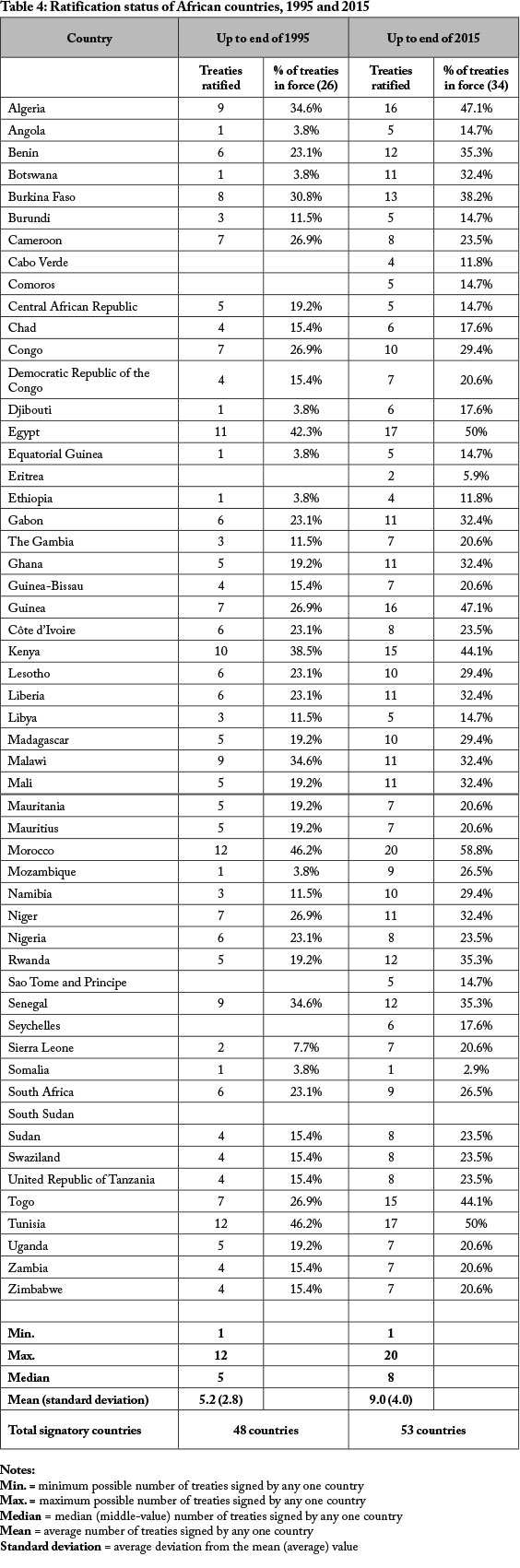

Table 3 (on pp. 64-65) presents the cumulative number of treaties ratified by each of 54 African countries, on or before 1935 and 1965. Table 4 (on pp. 66-67) presents the same information for 1995, and 2015. Both tables also display the relative adoption of treaties as a percentage of all IP treaties in force and available to be ratified at that time. And together the tables also provide-for each of the four years of study: 1935, 1965, 1995 and 2015-the minimum and maximum possible number of treaties signed by any one country, and the median, mean (average) and standard deviation for the number of treaties signed by the signatory countries.

Africa's colonial IP regime up to 1935

In October 1935, Italy, under Mussolini, invaded Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), marking the end of the "Scramble for Africa" and the "golden age of colonialism" (Mazrui & Wondji, 1993 p. 58; Shillington, 1989, p. 301). Economies across Africa were struggling to emerge from global recession. Italy's invasion of Ethiopia challenged international diplomacy, as the League of Nations was powerless to prevent aggression between two of its Member States.

Fifty years earlier, at the beginning of the "Scramble", the colonial powers of Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Spain formed an international (yet decidedly Eurocentric) IP union. The Paris Convention (1883) protected industrial property, including patents; the Berne Convention (1886) protected the copyright of authors and publishers; and the Madrid Agreements (1891) protected trademarks and the counterfeiting of goods. Later, the Hague Agreement (1925) protected industrial designs. These treaties were designed to extend the national IP policies of the colonial powers to as many markets as possible, with no substantive input from the colonised countries into the content of these treaties.

European powers agreed to carve up the continent of Africa at the Berlin West Africa Conference (1884-85), with the goal of controlling African markets (Shillington, 1989, pp. 301-05). IP treaties were, accordingly, used as instruments of colonial control of creative and industrial markets, in service to European rights-holders (Peukert, 2016, p. 40). For example, prior to 1886, authors in the colonies of the British Empire had to first publish their works in the United Kingdom in order to acquire copyright that would be valid in their home countries (Peukert, 2016, p. 41). Other colonial powers were more explicit in their discrimination. German legislation expressly prevented "eingeborne" ("natives") from holding rights to IP (Peukert, 2016, p. 41).

By 1935, according to WIPO, only three African countries (Morocco, South Africa, and Tunisia) had ratified international IP treaties. Morocco had ratified all of the five treaties in force at the time. South Africa had ratified one treaty. Tunisia, had ratified four treaties, three of which it was a negotiating party to: the Berne Convention, the Hague Agreement and the Madrid Agreement (Indications of Sources of Goods).

The Moroccan and Tunisian ratifications were effected through the colonial power, France, under which they fell. For example, a French law professor represented Tunisia in Berne, while French diplomats represented Tunisia in Madrid and The Hague (Peukert, 2016, p. 440). Figure 1 provides a graphical representation, as extracted from the aforementioned interactive web map application.

Not represented in Figure 1 (or earlier in Table 3) are the African colonies which were made subject to international IP treaties through the decisions of their colonial masters. Article 19 of the Berne Convention (1886) expressly gives "[c]ountries acceding to the present Convention [...] the right to accede thereto at any time for their Colonies." A similar provision was added to the Paris Convention, the Hague Agreement and the Madrid Agreements during the London Revision Conference in 1934 (Bodenhusen, 1969, p. 18). All colonial powers used these provisions during this period to unilaterally declare that treaty obligations extended to their colonies. However, we have not been able to include these data points in our dataset because these declarations are not readily available on any website we located. For example, WIPO notes under "Details" that France's ratification of Berne included colonies but does not specify which colonies, or when the treaty obligations took effect.

The period 1936 to 1965: IP's shift from colonial to post-colonial tool

In September 1940 Italian forces invaded Egypt, escalating confrontation on the African front of the Second World War. Throughout the war, French and British colonies provided troops and resources that were essential to the Allied war effort. After the war, rising African nationalism and Europe's reduced capacity to maintain control over the colonies led to a movement for independence across the continent (Shillington, 1989, p. 374). By 1965, 38 African countries had achieved independence (Shillington, 1989, pp. 373-406).

During this period of decolonisation, the Bureaux Internationaux Réunis pour la Protection de la Propriété Intellectuelle (BIRPI), the precursor to WIPO, worried that newly independent African countries would abandon the international IP regime. By this time it was widely recognised that developing countries benefited from relaxed IP protections. Additionally, the international IP regime maintains a Western paradigm of creativity and ownership that does not reflect African realities.

In March 1960, BIRPI sent a letter to newly independent African countries suggesting that they formally declare continued adherence to the international IP regime, for the sake of "legal security" (Peukert, 2016, p. 51). Around this time, a number of transnational organisations held seminars in Africa, promoting robust IP protections as essential for economic prosperity (Peukert, 2016, pp. 52-53). As a result, most newly independent countries declared membership in the international IP regime shortly after gaining independence.

Commentators point out that these attempts to stabilise international IP law were a form of neo-colonialism (Lazar, 1969; Peukert, 2016, p. 51; Rahmatian, 2009). Treaty membership imposed the same legal obligations as under colonial control, guaranteeing foreign ownership rights. At the same time, newly formed countries were prevented from developing IP policy to address local needs, including providing access to knowledge for education or protecting indigenous knowledge. Some of the countries were persuaded or pressured into adopting minimum standards which were not appropriate or even required of them, i.e., standards they were not, as least-developed countries, required to adopt (Deere, 2008a; Deere 2008b, pp. 241242). During the colonial era, tangible property rights had been the primary legal mechanism used to maintain foreign economic control; now, with decolonisation diluting some of the primacy of tangible property rights as economic control mechanisms, intangible IP rights began to come to the fore (Rahmatian, 2009, p. 42).

By 1965, 27 countries, roughly half of the continent, had ratified one or more international treaties, typically the Paris Convention (1883) and/or the Berne Convention (1886). On average, these 27 countries had ratified 1.8 treaties, with a median of 1 treaty. The number of African members in Paris grew to 22 countries, while African membership in Berne grew to 13 countries.

The number of multilateral IP treaties also grew during this period to include the Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonographs, and Broadcasting Organisations (1961), ratified by Congo and Niger. The Universal Copyright Convention (UCC) (1952) also gained traction in Africa, ratified by Ghana, Liberia, Malawi, and Nigeria.

The period 1966 to 1995: Limiting African influence: Stockholm, WIPO and TRIPS

In the summer of 1967, BIRPI member nations met in Stockholm for one of the last rounds of revisions to Paris and Berne. During the negotiations, developing countries, having finally received a voice at the table began to express their concerns. As a result, a less stringent "Protocol Regarding Developing Countries" was negotiated into Berne, which included a shorter copyright term and compulsory licensing (A compulsory licence is a non-voluntary licence, granted upon application, in specified circumstances to facilitate access to technology where the right-holder has refused to grant a licence. This enables developing countries to access technology which would otherwise not be available to them).2 Of the 13 African signatories to Berne at the time, 11 countries declared their intention to follow the Protocol.3

Many European countries did not approve of the Protocol, and at the next revision conference in Paris (1971), major revisions were made to create a global IP regime and close loopholes used by developing countries (Peukert, 2016, p. 54). These revisions aligned the more permissive UCC with Berne and implemented a more complicated and restrictive developing country protocol. However, few countries implemented this revised protocol. Some scholars have shown that the limited utility of this protocol was to some extent due to its complexity and certain unworkable provisions (Strba, 2012).

The 1967 Stockholm conference brought another significant change to the international IP treaty landscape, in the form of establishment of WIPO. WIPO took over from BIRPI in 1970 as the custodian of the Berne and Paris conventions and related IP treaties (Frankel & Gervais, 2016, p. 6). In 1974, WIPO became part of the United Nations. Prior to this, it was an intergovernmental organisation. By 1995, the 1967 UN Convention on WIPO (the treaty establishing WIPO) had achieved the highest level of adoption of any treaty at the time in Africa, with 43 member countries. The Paris Convention had the second highest adoption rate in Africa by 1995, with 39 ratifying counties, while the Berne Convention had 35 African adopting countries.

The period before TRIPS (which came into effect on 1 January 1995) saw the number of IP treaties increase. African countries ratified 13 new treaties in this period, for a total of 26 treaties in force by the end of 1995. Most of these new treaties addressed details of the industrial property and copyright regimes that were not specified in Paris or Berne. Other treaties broke ground on new areas of IP, including plant breeder's rights in the UPOV Convention (1961, 1971), and the Nairobi Treaty on the Protection of the Olympic Symbol (1981).

It is important to note that African countries had limited involvement with the initial negotiations for these 13 new treaties. On average, fewer than eight African countries participated in the forming each of these treaties. Significantly, of these participating countries, few chose to be signatories. Fewer than three African countries, on average, signed the treaties on ratification. African countries were most represented at the diplomatic conferences for the 1981 Nairobi Treaty (18 participants, eight signatories), the 1989 Washington Treaty (16 participants, four signatories), and the 1972 Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) (15 participants, six signatories). African countries were least represented at the 1978 and 1991 UPOV conferences (one participant, one signatory), the 1977 Budapest Treaty (two participants, one signatory), and the 1989 Madrid Protocol (three participants, three signatories). Notably, the aforementioned Nairobi Treaty (which had relatively strong African participation, with 18 participants and eight signatories) is among the least important for African economic and cultural development because it addresses a single specific issue: the use of the Olympic symbol. And the aforementioned Washington Treaty (16 African participants, four signatories) is not yet in force despite being formed in 1989. African countries were, thus, most-represented in the negotiations that mattered least.

Despite these challenges, the international IP regime continued to expand across the continent. By 1995, 48 African countries had ratified one or more treaties, with half of these countries having ratified five or more treaties. On average, African countries were bound by just over five treaties. The average country varied from the mean by (i.e., the standard deviation was) almost three treaties, indicating relatively large differences in treaty adoption. The five core instruments that had been signed by the majority of African countries by the end of 1995 were: Paris, Berne, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), the UN Convention on WIPO, and TRIPS.

The key IP treaty development in this period up to the end of 1995 is TRIPS. After the creation of WIPO in 1967, the developing world had become more vocal on IP issues. WIPO's structure had given developing countries a greater voice, making it harder for Western countries to implement their IP agenda. The developed world thus sought new strategies to limit developing-world influence. Developed nations brought IP into the realm of international trade, where their pre-eminence gave them greater influence, leading to the negotiation of the TRIPS Agreement as part of the creation of the WTO.

Negotiated during the establishment of the WTO, TRIPS is the most comprehensive and important IP treaty to date (Deere, 2009; Frankel & Gervais, 2016, p. 29). It includes and extends the previous IP regime under the Paris and Berne Conventions. Because the TRIPS Agreement was included as Annex 1С in the Marrakesh Agreement that founded the WTO, countries that wished to participate in global trade were required to adopt TRIPS. The Marrakesh Agreement was signed in 1994, and in 1995 it had legal effect in 33 African countries.

The TRIPS Agreement includes an enforcement mechanism, allowing infringing states to face trade sanctions before a WTO tribunal. The Agreement faced a crisis shortly after enactment, because its provisions compelled developing nations to purchase expensive HIV/AIDS treatments from Western patent-holders. In 1995, UNAIDS estimated that 4,039,000 people in Africa were living with HIV, with 181,200 deaths recorded on the continent in that year alone (UNAIDS, n.d.a, n.d.b). Millions of Africans died for lack of access to affordable anti-retroviral drugs in late 1990s, and it was only in 2001, via the WTO Doha Declaration, that it was made clear TRIPS did not prevent countries from taking measures to protect public health.

Specifically, the Doha Declaration's paragraph 6 mandated that a solution be found for countries with limited pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity which curtailed the benefits that they could garner from the use of compulsory licences. After the Declaration, in August 2003, the WTO adopted a decision on the Implementation of paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and public health (known as the "2003 Waiver"). Pursuant to a 2005 WTO Decision, the waiver has since been converted into an amendment to the TRIPS Agreement, as of 23 January 2017, after two-thirds of WTO Member States had accepted it. These accepting states included the following 16 African states: Botswana, Central African Republic, Congo, Cote d'Ivoire, Egypt, Gabon, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia. The amendment applies to those countries who accepted it, as of that date. Other WTO Member States have until 31 December 2019 to accept it and will remain subject to the waiver until then. However, the solution offered by the Declaration and amendment has proven cumbersome. For example, it requires that both the exporting and importing countries have to issue compulsory licences and advise the TRIPS Council of the import and export. Due to its complexity and laborious nature it has only been used once, by Rwanda and Canada (Abbott & Reichman, 2007; Andemariam, 2007; Ncube, 2018, pp. 686-687; Outtersen, 2010).

The period up to 1995 also saw the virtual completion of the African independence project. The Cold War came to an end in the period 1989-92, and this new geopolitical reality led to the spread of democracy and increasingly diverse participation in the global economy. Namibia gained independence in 1990, and Eritrea in 1993, and apartheid in South Africa came to an end in 1994. The only new African country that has come into being since the early 1990s is South Sudan, which gained independence from Sudan in 2011.

The period 1996 to 2015: Africa rising

Rapid and sustained economic growth in Africa over the past two decades has led some commentators to proclaim that Africa is "rising" (Economist, 2011). Other observers, however, warn that while there is indeed growth (Fosu, 2015), the Africa rising narrative fails to recognise the lack of structural change ( Jerven, 2015) with African economies still largely reliant on exporting resources and importing finished products (Taylor, 2014). Innovative responses to these structural challenges range from scaling up traditional textile products to MPESA, Kenya's mobile money transfer system (Adewopo et al., 2014; Mworia, 2016).

Also in this context, there is increased international focus on access- and benefit-sharing of genetic resources, with which Africa is richly endowed. This focus led to the adoption of the 2010 Nagoya Protocol, a supplementary agreement to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Protocol provides mechanisms to protect, ensure local community control of, and fairly reward use of, traditional knowledge (TK), acknowledging its roles in sustainable development, including responses to climate change.

While research is revealing how many African innovators are taking a collaborative approach to IP (De Beer et al., 2014), IP treaties continue to saturate the continent. Earlier in this article, in Table 4, we saw the high rates of subscription by African countries, in 2015, to most international IP treaties.

By 2015, all African countries except for South Sudan were party to one or more treaties. On average, African countries were bound by nine treaties, with a standard range of between five and 14 treaties. Half of all countries had signed eight or more treaties, with Morocco having signed the highest number: 20 treaties. Morocco was also involved in negotiation of the controversial Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), a separate agreement which has not come into force (and which was thus was not covered in our dataset). Most African countries are now covered by TRIPS. Of the 10 countries that are not members, all but four have ratified the Berne and Paris Conventions. Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and South Sudan are the only countries not bound to these foundational IP norm-making instruments.

At the same time, some new approaches towards treaty relations have emerged since the early 2000s-most notably via the aforementioned Doha Round of WTO TRIPS talks. Several important issues surfaced at these talks even though they were never completed. As stated above, one of the successful outcomes was the WTO Doha Declaration of2001 was intended to allow developing countries to more easily gain access to generic versions of patented anti-retroviral medicines to treat the AIDS epidemic (Love, 2011). The leadership of African states in the adoption of the Doha Declaration, beginning with Zimbabwe's call for a special TRIPS Council session on access to medicines, is well-documented (Odell & Sell, 2001 p. 85). In addition, within WIPO, African states' contribution to the adoption of the 2005 WIPO Development Agenda is also well-chronicled (Kongolo, 2013a). However, as previously noted, only 16 African countries have accepted the 2005 WTO Decision that culminated in the TRIPS Amendment which came into force in 2017. In view of the African continent's significant contribution to the initial impetus to adopt the Doha Declaration, the low uptake raises the question of why this impetus has not been reflected in the uptake of the 2005 Decision. Part of the answer to this conundrum is that the waiver solution has proven notoriously laborious and frustrating for developing countries, resulting in its minimal usage as noted above.

4. Conclusion: Opportunities for innovation

Consideration of the 131-year history of IP treaty adoption across Africa, from 1884 and 2015, provides insights into colonial, neo-colonial, independence-era and "Africa rising" patterns of African countries' engagements with the international IP system. The developed world continues, to a great extent, to impose IP norms that benefit rich-country rights-holders, while limiting African participation in negotiating new treaties. As a result, most international IP instruments do not reflect or support the realities in many African countries.

But despite the saturation of the African continent by rich-world-driven IP treaties, opportunities still exist for innovation by African lawmakers and policymakers. Although international norms are largely set by TRIPS, African countries vary considerably in their membership in a number of other relevant treaties. Additionally, implementation and enforcement, on the ground, vary from country to country. Made-in-Africa approaches to IP lawmaking and policymaking can undoubtedly produce benefits in terms of more inclusive innovation and, in turn, more inclusive and sustainable technological and economic development.

Our database potentially provides the beginnings of a tool through which we, and other interested researchers, can seek to use inferential statistics to examine potential relationships between nations' membership in certain IP treaties and: measures of human development; measures of innovation; and metrics of economic growth. Also, we used treaty ratifications as a proxy for the legal status of IP laws within each country. WIPO collates comprehensive and up-to-date information on each Member States' IP laws, thus providing potential for rich, qualitative legal assessments of nation laws and their degree of response to local realities.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out under the auspices of the Open African Innovation Research (Open AIR) network, with financial support from Open AIR, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), and the UK Department for International Development (DFID). This work is also based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa. Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the authors and the funders do not accept any liability in this regard. This article draws on the contents of a 2017 Open AIR Working Paper (De Beer, Baarbé & Ncube, 2017) by the same authors.

References

Dataset

Baarbé, J. (2016). Status of IP treaties in Africa, to 2015 [Interactive map] https://doi.org/10.23962/10539/2619

Baarbé, J., & De Beer, J. (2016). Status of IP treaties in Africa. [Database]. https://doi.org/10.23962/10539/2619

baarbeh. (2016). SoT-InteractiveMap. [Source code]. https://doi.org/10.23962/10539/2619

International legal instruments

Arrangement de la Haye Concernant le Dépot International des Dessins ou Modèles Industriels (Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs) 6 November 1925. Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/treaties/text.jsp?file_id=280732

Arrangement de Madrid Concernant la Répression des Fausses Indications de Provenance sur les Marchandises (Madrid Agreement Concerning International Registration of Marks) 14 April 1891. Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/treaties/text.jsp?file_id=281783

Convention de Berne pour la Protection des CEuvres Littéraires et Artistiques (Berne Convention Concerning the Creation of an International Union for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works) 9 September 1886. Retrieved from http://keionline.org/sites/default/files/1886_Berne_Convention.pdf

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), 1992.

International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, 2001. Retrieved from http://www.planttreaty.org

International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, Records of the Geneva Diplomatic Conference on the Revision of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, 1978 (UPOV 1981).

International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, Records of the Diplomatic Conference for the Revision of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, 1991 (UPOV 1992).

Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilisation to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS)), 2010

Protocol Regarding Developing Countries, Berne Convention for Protection of Artistic and Literary Works, as revised at Stockholm, 14 July 1967. Retrieved from www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=12801

Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties 6 November 1996, 1946 UNTS 3.

World Intellectual Property Organisation, Records of the Budapest Diplomatic Conference for the Conclusion of a Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure, 1977.

World Intellectual Property Organisation, Records of the Diplomatic Conference for the Conclusion of a Protocol Relating to the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks, 1989 (1991).

World Intellectual Property Organisation, Records of the Diplomatic Conference for the Conclusion of a Treaty on the Protection of Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits, 1989.

World Intellectual Property Organisation, Records of the Nairobi Diplomatic Conference for the Adoption of a Treaty on the Protection of the Olympic Symbol, 1981.

World Intellectual Property Organisation, Records of the Washington Diplomatic Conference on the Patent Cooperation Treaty, 1970 (1972).

World Trade Organisation, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), Annex 1C of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation, 1995.

World Trade Organisation, Ministerial Declaration on the TRIPS agreement and Public Health (held in Doha on 9-14 November, 2001), WT/MIN(01)/DEC/2, 4th Sess.

World Trade Organisation, Amendment of the TRIPS Agreement, Decision of 6 December 2005, WT/L/641, 8 December 2005.

World Trade Organisation, Implementation of paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health Decision of the General Council of 30 August 2003.

World Trade Organisation, Extension of the Transition Period under Article 66.1 for Least- Developed Country Members Decision of the Council for TRIPS of 29 November 2005, IP/C/40 30 November 2005.

World Trade Organisation, Extension of the Transition Period Under Article 66.1 for Least Developed Country Members Decision of the Council for TRIPS of 11 June 2013, IP/C/64 12 June 2013.

Secondary literature

Abbott, F. M., & Reichman, J. (2007). The Doha Round's public health legacy: Strategies for the production and diffusion of patented medicines under the amended TRIPS provisions. Journal of International Economic Law 10(4), 921-987. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgm040 [ Links ]

Adesida, O., Karuri-Sebina, G., & Resende-Santos, J. (Eds.). (2016). Innovation Africa: Emerging hubs of excellence. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing. [ Links ]

Adewopo, A., Chuma-Okoro, H., & Oyewunmi, A. (2014). A consideration of communal trademarks for Nigerian leather and textile products. In J. De Beer, C. Armstrong, C. Oguamanam, & T. Schonwetter (Eds), Innovation and intellectual property: Collaborative dynamics in Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Andemariam, S. W. (2007). The cleft-stick between anti-retroviral drug patents and HIV/ AIDS victims: An in-depth analysis of the WTO's TRIPS Article 31 bis amendment proposal of 6 December 2005. Intellectual Property Quarterly 4, 414-466. [ Links ]

Bodenhusen, G. H. C. (1969). Guide to the application of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property as Revised at Stockholm in 1967. Berne: Bureaux Internationaux Réunis pour la Protection de la Propriété Intellectuelle (BIRPI). [ Links ]

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). (n.d.). Parties to the Nagoya Protocol. Retrieved from http://www.cbd.int/abs/nagoya-protocol/signatories/default.shtml

De Beer, J. (2013). Applying best practice principles to international intellectual property lawmaking. IIC - International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law 44(8), 884-901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-013-0133-3 [ Links ]

De Beer, J. (2016). Evidence-based intellectual property policymaking: A review of methods and conclusions. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 19(5-6), 150-177. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12069 [ Links ]

De Beer, J., Baarbé, J., & Ncube, C. (2017). The intellectual property treaty landscape in Africa, 1885 to 2015. Open AIR Working Paper 4. University of Cape Town and University of Ottawa: Open African Innovation Research (Open AIR).

De Beer, J., Oguamanam, C. & Schonwetter, T. (2014). Innovation, intellectual property and development narratives in Africa. In J. De Beer, C. Armstrong, C. Oguamanam, & T. Schonwetter (Eds), Innovation and intellectual property: Collaborative dynamics in Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Deere, C. (2008a). The politics of intellectual property reform in developing countries: The relevance of the World Intellectual Property Organisation. In N. W. Netanel (Ed.), The development agenda: Global intellectual property and developing countries (pp. 111-133). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195342109.003.0005 [ Links ]

Deere, C. (2008b). The TRIPS agreement and the global politics of intellectual property reform in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Donohue, R. G., Sack, C. M., & Roth, R. E. (2013). Time Series Proportional Symbol Maps with Leaflet and jQuery. Retrieved from http://www.cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/view/cp76-donohue-et-al/1307

Economist. (2011, December 3). The hopeful continent: Africa rising. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/21541015

Forero-Pineda, C. (2006). The impact of stronger intellectual property rights on science and technology in developing countries. Research Policy, 35(6), 808-824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.04.003 [ Links ]

Fosu, A. K. (2015). Growth, inequality and poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recent progress in a global context. Oxford Development Studies 43(1), 44-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2014.964195 [ Links ]

Frankel, S., & Gervais, D. J. (2016). Advanced introduction to international intellectual property. Glos, UK: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783470501 [ Links ]

Gathii, J. T. (2016). Strength in intellectual property protection and foreign direct investment flows in least developed countries. Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law, 44, 499-554. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/gjicl/vol44/iss3/3 [ Links ]

Google Developers. (n.d.). Countries.csv. Canonical Concepts dataset repository. Retrieved from https://developers.google.com/public-data/docs/canonical/countries csv

Heller, M. A. & Eisenberg, R. S. (1998). Can patents deter innovation? The anticommons in biomedical research. Science, 280(5364), 698-701. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.280.5364.698 [ Links ]

International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). Convention notifications. Retrieved from http://www.upov.int/upovlex/en/notifications.jsp

Jerven, M. (2015). Africa: Why economists get it wrong. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Kongolo, T. (2013a). African contributions in shaping the worldwide intellectual property system. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315566009 [ Links ]

Kongolo, T. (2013b). Historical developments of industrial property laws in Africa. The WIPO Journal, 5(1), 105-117. [ Links ]

Kongolo, T. (2014). Historical evolution of copyright legislation in Africa. The WIPO Journal, 5(2), 163-175. [ Links ]

Lazar, A. H. (1969). Developing countries and authors' rights in international copyright. Copyright Law Symposium, 19. [ Links ]

Leaflet. (n.d.). An open-source Java script library for mobile friendly interactive maps. Retrieved from https://leafletjs.com

Lessig, L. (2004). Free culture: How big media uses technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity. New York: Penguin Press. [ Links ]

Love, J. (2011, September 16). What the 2001 Doha Declaration changed. Knowledge Ecology International. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.keionline.org/node/1267

Mapbox. (n.d.). Mapbox studio. Retrieved from http://www.mapbox.com/mapbox-studio

Mazrui, A. A., & Wondji, C. (Eds.). (1993). General history of Africa Volume VIII: Africa since 1935. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Muchie, M. (2016). Towards a unified theory of pan-African innovation systems and integrated development. In O. Adesida, G. Karuri-Sebina, & J. Resende-Santos (Eds.), Innovation Africa: Emerging hubs of excellence. Bingley, UK: Emerald. [ Links ]

Mworia, W. M. (2016). Mobile technology innovation ecosystem in Kenya. In O. Adesida, G. Karuri-Sebina, & J. Resende-Santos (Eds.), Innovation Africa: Emerging hubs of excellence. Bingley, UK: Emerald. [ Links ]

Ncube, C. B. (2016). Intellectual property policy, law and administration in Africa: Exploring continental and sub-regional co-operation. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315743714 [ Links ]

Ncube, C. B. (2018). Three centuries and counting: The emergence and development of intellectual property law in Africa. In R. C. Dreyfuss, & J. Pila (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of intellectual property law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ncube, C. B., Schonwetter, T., De Beer, J., & Oguamanam, C. (2017). Intellectual property rights and innovation: Assessing regional integration in Africa VIII. Open AIR Working Paper 5. University of Cape Town and University of Ottawa: Open African Innovation Research (Open AIR). Retrieved from http://openair.africa/2017/05/05/intellectual-property-rights-and-innovation-assessing-regional-integration-in-africa-aria-viii/

Odell, J. S., & Sell, S. K. (2006). Reframing the issue: The WTO coalition on intellectual property and public health, 2001. In S. J. Odell (Ed.), Negotiating trade: Developing countries in the WTO and NAFTA. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511491610.003 [ Links ]

Okediji, R. L. (2003). The international relations of intellectual property: Narratives of developing country participation in the global intellectual property system. Singapore Journal of International & Comparative Law, 7, 315-385. [ Links ]

Outterson, K. (2010). Disease-based limitations on compulsory licenses under Articles 31 and 31bis. In C. Correa, (Ed.), Research handbook on the protection of intellectual property under WTO Rules. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Peukert, A. (2016). The colonial legacy of the international copyright system. In U. Röchenthaler, & D. Mamadou (Eds.), Copyright Africa: How intellectual property, media and markets transform immaterial goods. Canon Pyon, UK: Sean Kingston Publishing. [ Links ]

Rahmatian, A. (2009). Neo-colonial aspects of global intellectual property protection. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 12(1), 40-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1796.2008.00349.x [ Links ]

Schneider, P. H. (2005). International trade, economic growth and intellectual property rights: A panel data study of developed and developing countries. Journal Development Economics 78(2), 529-547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.09.001 [ Links ]

Shillington, K. (1989). History of Africa. New York: St. Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Strba, S. I. (2012). International copyright law and access to education in developing countries: Exploring multilateral legal and quasi-legal solutions. Leiden, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004235403 [ Links ]

Taylor, I. (2014). Is Africa rising? (2014). The Brown Journal of World Affairs 21(1). [ Links ]

UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). (2016). Innovation, competitiveness, and regional integration: Assessing regional integration in Africa VII. Addis Ababa.

UNAIDS. (n.d.a). People living with HIV (all ages). Retrieved from http://aidsinfo.unaids.

UNAIDS. (n.d.b). AIDS-related deaths (all ages). Retrieved from http://aidsinfo.unaids.org

World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). (n.d.a). WIPO-administered Treaties. Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/

World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). (n.d.b). WIPO-administered Treaties, Contracting Parties > Berne Convention. Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ShowResults.jsp?lang=en&treaty id=15

World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). (n.d.c). WIPO-administered Treaties, Contracting Parties > Berne Convention > Stockholm Act (1967). Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ActResults.jsp?act id=23

1 Dataset available at https://doi.org/10.23962/10539/2619

2 See Protocol Regarding Developing Countries, Berne Convention for Protection of Artistic and Literary Works, as revised at Stockholm, 14 July 1967: http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=12801

3 See World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) (n.d.c).