Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The African Journal of Information and Communication

On-line version ISSN 2077-7213

Print version ISSN 2077-7205

AJIC vol.20 Johannesburg 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.23962/10539/23576

ARTICLES

Development of a communication strategy to reduce violence against children in South Africa: A social-ecological approach

Mark EdbergI; Hina ShaikhII; Rajiv N RimalIII; Rayana RassoolIV; Mpumelelo MthembuV

IAssociate Professor, Center Director, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

IIDirector of Program Management and Research Operations, Center for Social Well-Being and Development, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

IIIProfessor and Chair, Department of Prevention and Community Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

IVCommunication for Development Specialist, UNICEF South Africa, Pretoria

VManaging Director, Gosiame Research and Marketing, Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

Research on violence against children, though extensive, has not been effectively deployed for the development and tailoring of communication efforts aimed at specific national, local and cultural contexts within which such violence occurs. This article presents a staged, multi-sectoral communication strategy to reduce the incidence of violence against children in South Africa. Drawing on formative data collected through a literature review, key informant interviews, focus groups, and a stakeholder review meeting, the research team, in collaboration with UNICEF South Africa, formulated a communication strategy aimed at combatting violence against children. The data analysis and strategy development within a social-ecological framework sought to identify factors at multiple levels that contribute to violence against children in the South African context. The communication strategy is designed to achieve positive social and behaviour change outcomes in South Africa with respect to the treatment of children, and also to provide an approach as well as specific elements that are potentially replicable to some extent in other countries.

Keywords: violence against children, behaviour change, prevention, South Africa, communication strategy, social-ecological approach

1. The scope of violence against children and gaps in communication approaches to address the issue

Violence against children is a multifaceted problem and globally widespread (UNICEF, 2014). At the same time, the accumulation of research and practice in public health communication has a great deal to contribute in preventing such violence, though it has not yet been applied in any significant way to this issue. Hence, relatively little is known about effective communication approaches for designing, implementing, and evaluating campaigns to address a problem that is at once ubiquitous, hard to define, and often hidden. Our working assumption in this article is that a communication framework can serve as a valuable tool for change in large audiences, as well as for future research. Based on the development of a communication-for-development (C4D) strategy for UNICEF to reduce violence against children in South Africa, we present a communication framework that, we hope, can be adapted for application both in South Africa and in analogous settings. Communication-for-development refers to a broad term employed by United Nations agencies to describe a social process aimed at promoting dialogue within communities and between communities and policymakers, to facilitate the achievement of human development goals (UNDP, 2011).

Violence against children as a global problem

Violence against children manifests in different forms, including physical violence (fatal and non-fatal), sexual violence, exploitation, violent discipline/corporal punishment, emotional violence, neglect and negligent treatment, and bullying, both physical and psychological (UNICEF, 2014; WHO, 2012; Pinheiro, 2006). In 2012, approximately one in five homicide victims worldwide were children and adolescents under the age of 20 (UNICEF, 2014). Moreover, violence against children is commonplace, and it intersects with other factors, including disabilities, ethnicity and gender (UNICEF, 2014; UN, 2014). The problem occurs in numerous settings ranging from the home, schools, work places, communities, institutional care sites, juvenile justice systems, and via the Internet in the form of cyber-bullying (UNICEF, 2014). Social and cultural norms and beliefs, religious imperatives, socioeconomic status, non-existent or weak legislative and enforcement frameworks, and underreporting are all contributing factors (Pinheiro, 2006; Landers, 2013). Children are also subjected to violence in trafficking, armed conflict (including the exploitation of children by gangs and opposition movements), and by harmful, sometimes fatal, practices such as female genital cutting and child marriage (UN ECOSOC, 2008).

United Nations efforts

In cooperation with host countries, UNICEF has been at the forefront of worldwide efforts to develop and implement a range of approaches to child protection. These efforts, including communication interventions, are grounded in a human rights foundation, based on the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and are tied to the following elements: (1) strengthening national protection systems; (2) supporting social change; and (3) promoting child protection in conflict and natural disasters. Crosscutting areas include (1) evidence-building and knowledge management; and (2) convening and catalysing agents of change (UN ECOSOC, 2008).

Other global and UN agencies also have taken on this issue. The prevention of violence against children, particularly gender-based violence, was included in multiple efforts to meet the 2000-2015 Millennium Development Goals (Fehling, Nelson, & Venkatapuram, 2013). The seminal 2002 UN World Health Organisation (WHO) report on violence and health concluded that violence against children and women is a global priority, and called for a public health, science-based approach to complement criminal justice and human rights responses (WHO, 2002). Further, the 2006 UN World Report on Violence against Children called on governments to prioritise prevention and allocate sufficient resources to address risk factors and underlying causes (Pinheiro, 2006). WHO continues to advocate for a public health-based, preventive approach to child maltreatment (WHO, 2013). Finally, in pursuit of the global targets set out in the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, UNICEF promulgated An Agenda for #EVERYChild 2015 in which the first item calls for an end to violence against children (UNICEF, 2015).

Existing research insufficient

A brief summary of relevant research literature is useful as a point of reference, with a caveat that the literature often conflates communication and other types of violence-prevention interventions. Important for the strategy discussed in this article, key factors hindering the effectiveness of interventions to prevent violence against children, including communication efforts, have been knowledge gaps and the implementation of approaches that are not well-tailored for the intended audience or that lack a sufficient evidence base. Additionally, data suggest there is insufficient dialogue in low- and middle-income country settings between work in early child development and work in violence prevention - dialogue that could help harmonise efforts to address these two intersecting phenomena and balance the current predominance of such research and evidence from high-income countries (UBS Optimus Foundation & WHO, 2013).

Few evidence-based communication or community-based efforts to change the social norms that support violence against children exist, and fewer still are sufficiently tailored to a particular country or community context (UBS Optimus Foundation & WHO, 2013; Fulu, Kerr-Wilson, & Lang, 2014). In fact, a large majority (90%) of studies on violence prevention, early child development, and parenting interventions have been published in high-income countries, specifically, the United States and Canada (Knerr, Gardner, & Cluver, 2011; UBS Optimus Foundation & WHO, 2013). Moreover, a review of a sample of UNICEF country programs showed that data on violence against children are also hampered by "differences in terminology, variations in cultural/social interpretations, and the validity, representativeness and coverage of data, including baseline data which is often absent" (Landers, 2013, pp. 23-24). In short, there is a weak and fragmented evidence base on this important topic (Landis, Williamson, Fry, & Stark, 2013; Bott, 2014).

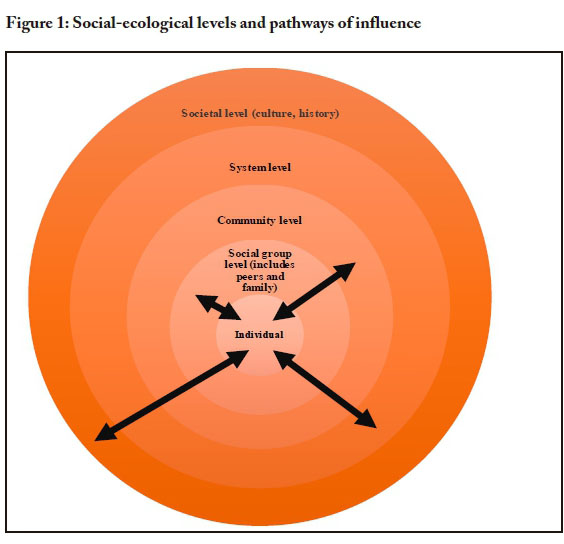

In addition to the lack of reliable and representative data, evaluations of intervention effectiveness are often flawed and do not even measure decreases in violence as an outcome (Fulu, Kerr-Wilson, & Lang, 2014). Within the spectrum of possible intervention points, programming focused on prevention derives from a stronger evidence base (Bott, 2014). Recent research has recommended that a public health, social-ecological approach through the life cycle be incorporated in developing, monitoring and evaluating efforts to prevent violence against children (Chan, 2013; Fegert & Stötzel, 2016; Sood, 2015; UBS Optimus Foundation & WHO, 2013; Van Niekerk & Makoae, 2014). A social-ecological approach means to identify and address contributing factors that extend beyond the individual, through multiple levels including family, community, and the broader socio-cultural context, drawing on Bronfenbrenner's ecological model of human development (1979) and subsequent public health applications (Stokols, 1992, 1996; see also USCDC, n.d.). Using a social-ecological approach through the life cycle refers to the identification of the multi-level contexts salient at different life stages, and their incorporation in program design and evaluation (see, for example, Edberg et al., 2011).

The UNICEF-sponsored effort to address violence against children in South Africa

This article describes an effort to utilise formative research in the development of a tailored, multi-component, phased strategy as a guide for a UNICEF and government of South Africa collaborative campaign, using a C4D intervention, to reduce violence against children. Working with UNICEF, the research team conducted a literature review, formative qualitative research, and stakeholder meetings as a foundation for the strategy. The aim was to understand the forms and contexts in which South African children face violence, and to identify specific approaches, channels, and messages - both informational and persuasive - that would be suitable for both national and local communication interventions.

The formative research was oriented around a social-ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Knerr, Gardner, & Cluver, 2011; Stokols, 1992; 1996), in order to identify specific contributing factors at multiple levels that could be included in a communication strategy (Burton, 2012). It was understood during this process that aspects of broader contributing factors in South Africa could be implicated, including the impact of poverty, enduring impacts of apartheid, existing social and cultural norms and practices, the role of social institutions, legal and policy frameworks (and their implementation), and the allocation of resources (UBS Optimus Foundation & WHO, 2013).

The social-ecological framework we used employs two major dimensions: (1) levels of influence, moving from the individual out to broader societal factors; and (2) pathways of influence, linking factors at one level to those in another, both as a means of understanding causality and of guiding the change process advocated through the communication strategy. Thus, for example, system-level factors - e.g., the lack of capacity and training among child and family serving agencies to address violence victims - have an influence on individual decisions to report violence against children and to seek treatment. As described later in this article, one campaign focus (through a media advocacy component) could therefore be directed to improving these systems, with the assumption that doing so would contribute to changes in individual decisions. Or, if exposure to, and normalisation of violence is a factor that contributes to behavioral norms at the societal, community, family and peer levels, then the campaign should include multiple components at different levels seeking to break the pattern of normalisation.

Figure 1 (next page) illustrates this approach.

The overall research question guiding the effort was as follows: What kind of C4D strategy would be most effective in combatting violence against children in the South African context, and how would such a strategy be empirically and theoretically grounded?

2. Methods

The proposed communication strategy was developed through an intensive, collaborative research process that included the following steps:

-

An extensive literature review that included use of general online search tools, consultation of significant research reports provided by UNICEF and key research institutions (e.g., the University of Cape Town Children's Institute), and specific database searches (e.g., LexisNexis, Google Scholar, PsychINFO, JSTOR, Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, AnthroSource);

-

Meetings and discussions with UNICEF South Africa topical experts;

-

Semi-structured interviews with identified local key informants (referred to in this article as expert respondents) to elicit information that would help to understand and inform knowledge gaps in the literature and prioritise those with respect to project relevance;

-

Conduct of four focus group sessions (total n=33) with samples of parents, youth, teachers, and social service practitioners, to gain information on general attitudes, beliefs and experiences concerning the issue of violence against children in South Africa, and feedback on ideas for the communication strategy; and

-

A stakeholder meeting in Pretoria, South Africa, that included representatives from media, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), service providers who work with victimised children, government ministries, and UNICEF.

Topical experts and key informants were drawn from the following domains/sectors: experts in child development from South African universities; treatment providers for children who are victims of violence; representatives from South African NGOs that conduct relevant communication efforts; broadcast media organisations; the Department of Social Development; and local NGOs advocating for child rights.

A partner organisation in South Africa specialising in qualitative research conducted the focus group discussions. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling strategy (Bernard, 2011), working through existing contact networks from our research partner and UNICEF. Collected data were transcribed and then analysed for key themes using QSR International NVivo, qualitative data analysis software for researchers. (A listing of key informant interviews and focus groups is at the conclusion of the References section below.)

Research findings were compiled and used to inform the development of a sequenced communication strategy and its theoretical justification. Relevant stakeholders in South Africa reviewed the draft strategy prior to its finalisation.

3. Findings from the literature review and formative research

Context of child violence in South Africa

Data reviewed in this section are drawn from the literature reviewed and pertinent data collected from the qualitative research, including the key informant interviews and focus groups as a means of triangulation.

Violence against children should be viewed in the context of the broader environment of violence in South Africa. In 2015, based on 2010-2012 data, South Africa was said to have the second-highest rate of gun-related deaths in the world, at 9.4 per 100,000 (BusinessTech, 2015). South Africa also ranks high in rates of interpersonal violence and violence against women (DSD, DWCPD, & UNICEF, 2012). Reliable, comprehensive data specifically on violence against children are, however, difficult to come by, thereby hampering a full understanding of the extent of the problem (UNICEF, 2014). In general, violence involving adolescents (typically meaning children between ages 10 to 19) is often connected to community violence and crime, whereas violence against younger children, age five and under, most typically occurs in the context of family (UCT, n.d.).

There is no one source of comprehensive data; however, multiple sources attest to the widespread nature of violence against children. By one report, 827 children were murdered in South Africa in 2012-13, and 21,575 children were assaulted (Gould, 2014). At the 52 Thuthuzela Care Centres that provide "one-stop" services to victims of sexual assault and rape, for fiscal year 2013-2014, a total of 30,706 matters were reported, of which 2,769 pertained to trafficking, domestic violence or matters governed by the Children's Act of 2005, and the overwhelming balance concerned sexual offences (Department ofJustice and Constitutional Development, 2014). The South African Medical Research Council, in an examination of child homicide rates by age, found that the highest risk of death for girls was in the 0-4 age group with a rate of 8.3 per 100,000, while the highest risk of death for boys was in the adolescent 15-17 age group with an alarming rate of 21.7 per 100,000 (Mathews, Abrahams, Jewkes, Martin, & Lombard, 2012). In the 0-4 age group, there was only a 0.7 difference in the homicide rates for girls and boys; however, the overall male child homicide rate was almost double that of the female child homicide rate because of the substantial mortality rate of male adolescents (Mathews et al., 2012).

Child violence in South Africa occurs in multiple settings (Mathews, Jamieson, Lake & Smith, 2014, p. 43; Proudlock, 2014, p. 173). A pilot child death review conducted by the University of Cape Town found that of the children and babies who died in 2009, 44 % were killed in connection with violence (Nicolson, 2015). Corporal punishment appears to be relatively widespread in South Africa, even in schools where it is against the law (Van der Merwe, Dawes, & Ward, 2012). Some sources have indicated that corporal punishment is more prevalent in rural and poorer provinces or areas, with a high degree of continued use found in KwaZulu-Natal Province (Burton & Leoschut, 2013). Traditional practices involving violence against children, such as virginity testing, also appear to be more prevalent in rural than urban areas (Curran & Bonthuys, 2004; UCT, n.d.). Additionally, the World Bank and other sources have identified bullying and cyber-bullying as problems among South African children (Burton, 2012). Supporting the latter assessment, youth in one of the focus group discussions for our research expressed a considerable amount of concern over cyber-bullying, including harassment via the social media platform Instagram. There is also violence directed to specific categories of children, including the disabled, children from immigrant families, street children, and those with HIV/AIDS, as well as evidence of discrimination and violence, in Southern and East Africa, against children with albinism (The African Child Policy Forum, 2014).

Children are victimised not only by adults but also by their peers. One expert respondent from a treatment setting, interviewed during our research, estimated that as many as 40% of her clients were affected by peer violence. Children as young as age 5, she said, are perpetrators as well as victims. Peer-on-peer violence, according to another NGO expert respondent, also includes sexual abuse. Data show that peer violence in schools ranges from threats of violence and assaults to sexual assaults and robbery (Burton, 2012). A study conducted by South Africa's Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation concluded that peers are significant perpetrators of homicide and rape, with the 15-34 age group comprising 9 out of 12 (75%) of suspects for victims ages 14 and younger, and 42% of rapes committed against children under age 12 (Graham, Bruce, & Perold, 2010). Thus because child violence includes both perpetration and victimisation, against what appears to be a backdrop of normalised violence, a third expert NGO respondent said that there is a shift in thinking, from a conceptualisation of "violence against children" to the notion of "violence in childhood", which is seen as a more adequate description of the situation.

A social ecology of causal factors for violence against children in South Africa

Following the social-ecological approach outlined earlier, we understand violence against children in South Africa as the outcome of multiple, interacting factors. While we cannot detail all the formative evidence herein, the literature review and the qualitative formative research support a general understanding that, at the broader, distal levels, factors include gender norms and the continuing impacts of apartheid on violent behavioural patterns through, among other means, the cultural normalisation of violence (from high exposure), and socioeconomic inequity linked to family fragmentation (Edberg, Shaikh, Thurman, & Rimal, 2015).

At the more proximal levels, the data from the literature and formative research point to substance abuse; community-violence exposure and victimisation; difficult family circumstances and partner violence; school violence (including peer-to-peer violence, in-person or virtual); vulnerability of specific population subgroups including infants, HIV/AIDS orphans, and immigrants; traditional practices such as bride-stealing, virginity testing and circumcision; common cultural practices regarding discipline of children; a lack of capacity by social, health and police services to provide adequate prevention and intervention; and low levels of awareness and trust in these services (Edberg et al., 2015).

Normalisation at multiple levels

One expert respondent described the underlying atmosphere of normalised violence as follows: "People learn violence as a language; it's so ingrained that even before they learn to speak, they learn violence." A youth focus group participant underscored this description, saying that violence "is the only world we know." In a statement issued by the University of Cape Town, a development policy expert was quoted as saying:

Due to the normalisation of violence in South Africa's past, there is now a widespread tolerance of it. So we need to work very hard to break this cycle. This requires an attitude that preventing violence is everyone's business: government, civil society, religious and traditional leaders, communities, caregivers, children, the media... all have a positive role to play in saying no to violence against children. (UCT, 2014, p. 3)

Youth respondents even talked about the normalisation of cyberbullying. The youth who are not bullied "are not taking it serious because it is like you are being desensitised of the whole thing because we [are] growing up watching bullies on TV and everything else so it becomes normal to you." Yet another youth said, "it starts social [social media] and goes to physical."

Causal links between social-ecological levels

Links can be drawn between the distal and proximal levels of causation. Respondents in focus group discussions with social workers and parents, for example, pointed to family breakdown and poverty, and their association with substance abuse and family violence, as a syndrome correlated with violence against children, particularly neglect and lack of protection. For instance, one respondent noted, "[Violence] is also linked to the social economic conditions in South Africa as a whole. Because socially the family structures are really destroyed in our country." This was echoed by another respondent stating, "Yes, [family structures are] almost non-existent." Economic factors also play a role, as a third respondent expressed, "[M]ost of the parents are not working. In the morning they go to drink. Sit in there drinking the whole day. They don't care about the children. And they [are] angry and frustrated and the first person that is suffering are the children when they get home." There also was a link made to a general breakdown in cultural values, including a change from collective to more individualistic relationships.

Moreover, at the family level, the normalisation of violence is embedded in traditional childrearing practices. In some contexts, parents and teachers do not see corporal punishment as constituting abuse. According to one service-provider focus group respondent, "Children need to be disciplined but because not all parent[s] know the difference between discipline and abuse[,] we should teach parents that there are other ways to discipline your children. You know, let them stand in a corner, you know. Withhold certain treats." Physical discipline is customary in certain South African contexts, and to move towards changing this practice, parent respondents suggested that allowing parents who practice corporal punishment to get more exposure to the practices of parents who do not use such punishment, along with exposure to positive messages, would be useful. Some parent respondents also cited the usefulness of support from other community members when, for example, there are many single-parent households in a community. At the same time, there were concerns expressed about the potential for loss of authority over children in the absence of the sanction of corporal punishment.

At the government level, there is a substantial body of law that protects and promotes child rights. Despite this strong legal foundation, there are multiple barriers through lower social-ecological levels, including the community and family levels, with respect to implementation. Enforcement remains weak across national and provincial government departments, with respect to both prevention of violence against children and adequate response to incidents of such violence (Proudlock, 2014). Moreover, the social context is complex; child abuse cases may entail complicity by families, the police and other services (Richter & Dawes, 2008).

South African C4D efforts to address violence against children

South Africa has a rich media environment, and government, private and non-profit media organisations have been involved in initiatives to address interpersonal violence and raise public awareness of the negative impacts of violence, including violence against children. Government-sponsored efforts include the annual 16 Days of Activism for No Violence against Women and Children campaign; Child Protection Week, hosted by the Department of Social Development (DSD) since 1998; and participation in the UN's UNiTE to End Violence against Women campaign (DSD, DWCPD, & UNICEF, 2012). The South African Integrated National Programme of Action Addressing Violence against Women and Children (2013-2018) includes, as a key objective, a call to "prevent violence from occurring through a sustained strategy for transforming attitudes, practices and behaviours" (DSD, 2014, p. 25).

A number of NGOs in South Africa have implemented public communication campaigns to address violence against both children and women. Perhaps the most notable and widely recognised efforts are those conducted by the Soul City Institute for Social Justice (Soul City Institute), based in Johannesburg. Soul City employs an "edutainment" or "infotainment" approach, harnessing popular culture and communication via mass media in an effort to bring about social change through entertainment delivery modes. Soul City activities have included dramatic soap-opera style ("soapie") TV series, radio programmes, and accompanying print materials, including a series focusing on alcohol and violence (Phuza Wise); the Kwanda ("to grow") reality TV show focused on community mobilisation and improvement; and the Soul Buddyz television and multimedia series aimed at promoting health and well-being among children aged 8-12.

Resources Aimed at the Prevention of Child Abuse (RAPCAN) is a South African NGO engaged in activities to help address violence against children, including some communication interventions directed at parents, educators and communities, and some advocacy to end corporal punishment. Another South African NGO, Sonke Gender Justice, focuses on HIV/AIDS issues and sexual and reproductive health rights, and has implemented advocacy campaigns aimed at promoting child rights, including community mobilisation and media campaigns in partnership with Promundo to increase men's involvement in nonviolent parenting (Sonke Gender Justice, n.d.). The loveLife NGO primarily addresses HIV prevention among youth, and tis work intersects with child violence issues because of its focus on broader social determinants of risk. Research shows, for example, that childhood sexual and physical abuse contributes to later, HIV-transmission-causing sexual risk behaviour and victimisation through early sexual initiation, unprotected sex, and use of alcohol and drugs during sexual activity (Richter et al., 2014). The loveLife programme's initiatives have included peer educator programmes, media campaigns, local community dialogues, and a Cyber Y programme for youth that combines computer literacy training with information about healthy sexuality and lifestyle choices.

There is not yet a sufficient body of evidence assessing the effectiveness of specific C4D initiatives in preventing and responding to violence against children in South Africa. For example, reports summarising two of the primary public awareness activities, DSD's Child Protection Week and the 16 Days of Activism for No Violence against Women and Children campaign, do not include any measurement or evaluation of effectiveness (Van Niekerk & Makoae, 2014). And according to the South African Child Gauge 2014, "statistics on reported violence against children have not reduced substantially in the past two decades" (Van Niekerk & Makoae, 2014, p. 38).

While not extensive, there have been some evaluations of the effectiveness of Soul City's C4D efforts, with evidence found of positive attitude change regarding the acceptability of violence (Soul City Institute, n.d., 2011). Soul City deploys a variety of measurement methods, including quantitative baseline and follow-up surveys, and some qualitative data (Soul City Institute, 2016). An evaluation of a Soul City intervention to address domestic violence found a 14 % increase in agreement with a statement that no woman deserves to be beaten, and the same percentage increase in awareness about a national helpline connecting Soul City audiences to assistance for domestic violence (Hillis et al., 2015; Usdin, Scheepers, Goldstein, & Japhet, 2005). The intervention also correlated with a shift in attitudes, showing a 10% increase in respondents disagreeing that domestic violence was a private affair (Usdin et al., 2005). Soul City evaluations assessing some of its multimedia programs that include youth as a target audience show increases in HIV/AIDS knowledge and condom use among youth (Soul City Institute, 2016). There is also some evidence of impact among youth of loveLife programmes (Peltzer & Chirinda, 2014). In addition, outside South Africa, there is evidence that communication programmes have decreased the acceptability of violence against intimate partners and children (Promundo, 2012).

It bears noting that some of Soul City's evaluation documents appear to be incomplete. For example, a 2007 evaluation report on a health promotion intervention involving multimedia components cited a nationally representative sample of approximately 1,500 people interviewed over three consecutive years; however,outcome measurement and reporting focused only on a one-year sample (Soul City Institute, 2007).

4. Social-ecological analysis underlying the communications strategy to address violence against children

Theoretical basis

The formative research identified both broad, distal contributing factors (e.g., behavioural legacy of apartheid), as well as more proximal factors at the levels of institutions, communities, families, and individuals, that contribute to violence against children in South Africa. The broader factors identified tend to be historically and societally embedded and thus likely slow to change, while some of the proximal factors would likely be conducive to shorter-term change. Accordingly, we, along with the rest of the research team, concluded that a communication effort would need to operate at multiple levels (i.e., follow a social-ecological approach), and be staged (i.e., progress through several stages and target population levels) to be effective and optimise the best combination of campaign components.

It should also be noted that the formative data suggested the need for stages even at the highly proximal, individual-factor level. For example, a parent might receive or hear information regarding the use of non-violent disciplinary practices. Yet if parents perceive these practices to be normative (in part due to cultural traditions, in part because of the general normalisation of violence as documented in the formative research), the information would likely need to be strengthened by follow-up (i.e., staged) components employing social support and modeling from other parents to translate the information into action.

Multiple social and behaviour change theories support a staged communication strategy. As an overall framework, we drew on the premise of the trans-theoretical model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983; Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2002) that behaviour change is a staged process, not a single event. Implied is the idea that addressing readiness to change must be included as part of in the behaviour change process, and that messages and strategies need to be tailored to a succession of change stages and their differing requirements. Second is diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers, 1995), which characterises the adoption of a new behaviour or technology as occurring through stages within a diffusion context that includes the social and cultural environment, and can be facilitated via change agents. Third is social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986; 2001), focusing on the person-environment interaction as a mechanism for change, in which individual change is facilitated by behavioural models, skill-building, social support, and positive reinforcement from one's social environment, leading to greater behavioural self-efficacy. Linked to this is social support theory (House, 1981; Berkman & Glass, 2000), focusing on the importance of several types of social support to reinforce behaviour change.

Fifth is a set of communications-related theories, in particular social marketing/ branding theory and media advocacy theory. Social marketing/branding theory (Evans et al., 2011; Hecht & Lee, 2008; Kotler, Roberto & Lee, 2002) likens the adoption of behaviour to adoption or purchase of a product. The marketing task involves linking the behaviour to desirable attributes that would enhance its attractiveness, such that the behaviour represents those attributes, as in a "brand". Media advocacy theory (Dorfman & Krasnow, 2014; Wallack, 1994) focuses on the use of media techniques for agenda-setting and public policy change. Finally, we drew on cultural theory (summarised in Edberg, 2013, as it pertains to health), which emphasises the embedded nature of behaviour, such that a behaviour cannot be considered or addressed outside the socio-cultural context that gives it meaning and value, and that in turn contributes to constraints and facilitators concerning specific behavioural options.

Based on the data collection and analysis, we have outlined below a framework and approach for a staged communication strategy. Each phase of the strategy draws on descriptive and causal data based on the formative research, and is linked to one or more of the theoretical perspectives outlined herein, depending upon the message content and target audience(s) for that phase. For example, the broad media campaign provided in phase one is intended to introduce and frame a coherent message about violence against children. For this purpose, branding theory is pertinent, as the goal is to establish a unified identity for the campaign. In phase three, on the other hand, the goal is to provide social support and models to facilitate individual behaviour change; thus social support theory and social cognitive theory are relevant in structuring the communication activities in that phase. And, in keeping with a social-ecological approach, the communication strategy assumes that the environment for behaviour change - specifically in this case, the social, legal and health service infrastructure, as well as political commitment - must also evolve in order to facilitate successful actions by individuals and groups.

Objectives implemented through a staged process

It is our view that a communications campaign addressing violence against children for South Africa as a whole cannot effectively target, as its primary end, broad distal factors such as the legacy of apartheid and continuing economic inequality, because these factors underlie multiple phenomena and could therefore obscure the clarity of the intended behavioural change goal. This is not to say, however, that these factors are not significant, and it is part of the central problematic addressed in this communication strategy to target the normalisation of violence and the behavioural implications of that normalisation that are consequences of that legacy. This is a key theme underlying sample campaign activities at multiple levels described below. Beyond that, the strategy seeks to identify motivators of change, facilitators of change, as well as facilitators of sustainable change, and to integrate these into a coordinated programme of action.

The overall behavioural goal is to reduce the incidence of violence against children. A communication campaign, however, constitutes only part of the process of reaching that goal, and must be integrated with a comprehensive undertaking that includes the implementation of adequate policies and regulations, law enforcement, prevention programming, and treatment services. Thus, the overall goal is to influence knowledge, attitudes, practices, and the supportive environment so that violence against children is not viewed as normal, but as harmful and antithetical to personal aspirations in a changing South Africa progressing beyond the legacy of apartheid as a broad background motivation, and to motivate and persuade multiple audiences in a movement to change behaviour over time through a series of coordinated stages addressing more proximal factors.

Specific campaign objectives are based on promoting behaviour change as a staged process (per our theoretical framework), in which members of the target populations: (1) first become more aware of violence against children and its negative consequences, and understand personal efficacy in avoiding the proscribed behaviour; (2) then come to value and associate a reduction in violence against children with personal and South African progress (the brand); 3) are then motivated and socially supported by the linking of the behaviour change to a social movement that is a positive alternative from which they are more likely to experience valued outcomes; (4) are individually supported through instruction messages, modeling and positive reinforcement regarding how to change the risky behaviour; and (5) are then further supported in maintaining the positive behaviour over time by improvement in the service infrastructure.

Our formative data were used to identify not only causal factors, but also communication channels, themes, messages and activity types were used to develop the strategy. Communication activities under the strategy would be conducted as needed in English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Sotho, and Xhosa, and - for community radio and community action teams - the language(s) appropriate to the specific audience.

5. Results of the analysis: A phased communication strategy to address violence against children at multiple social-ecological levels

Figure 2 (next page) illustrates the overall flow from causal factors to themes/ messages, communications channels, and target audiences, and then to campaign activities.

Based on our analysis, the following represents an example of a hypothetical, staged C4D campaign that could be implemented via a collaborative engagement by UNICEF and the South African government, and at a community level, to empower NGOs, schools, and private businesses or organisations, and sustain campaign initiatives. The campaign description provided is an overview, with objectives, target audiences, key themes and messages, communications channels, activities, and potential evaluation approaches for each phase. Importantly, it is designed to address contributing factors at the multiple social-ecological levels described thus far, in a coordinated sequence.

Phase one: Establishing a campaign brand and addressing societal-level factors

The intent of a first campaign phase (estimated duration of one and a half years) is to address the normalisation of violence, a key causal factor in the social-ecological spectrum outlined thus far, and to introduce an agenda that reframes violence through a branding process. Moreover, normalisation of violence permeates multiple levels, and is broadly associated with South Africa's past. Thus a reframing effort through branding would seek to link the reduction of violence against children to future aspirations. As part of that objective, the first phase needs to increase awareness that violence against children is harmful and antithetical to individuals, families, schools and communities in a changing South Africa. Three aims follow from this objective: (1) clarify the definition of violence so that target populations understand what is at issue; (2) brand the reduction of violence against children as aspirational, empowering, and forward thinking; and (3) frame the reduction of violence against children as a social movement in order to facilitate collective action by multiple groups. Target audiences are the general population, including youth, parents, educators, and community leaders because the objective is to address a broad societal-level theme.

This phase includes an important definitional element that supports the ability of individuals, particularly in a family context, to recognise violent behavior. The definitional aspect of this phase could employ communication strategies that include the presentation of scenarios depicting violence against children with taglines such as "This is not love. This is violence." A tagline with this message would be an attempt to address, as documented in the formative research, the normalisation in South Africa of violent discipline and its consideration as a time-honored method to regulate children's behaviour. This family-level message should be linked to the broader social context, as a foundational theme tying a reduction of violence against children to a new South Africa, intended to impart a positive and aspirational "brand identity" to reducing violence, instead of a critical or negative tone (a point emphasised by stakeholders). Importantly, this theme would best be positioned as the goal of a "movement" - a social action form that is familiar and popular in South Africa, according to stakeholders who provided feedback on the proposed strategy -and as a goal that requires collective action. The theme would seek to position youth, parents, and community leaders as agents of change.

Because broader themes are involved that do not target a specific demographic or community, we concluded that the objectives of phase one would be best accomplished through a coordinated mass media campaign together with social mobilisation. As the kickoff and "agenda-setting" phase, we consider it important that this phase engage all possible communications channels, including: (1) major media, through public service announcements (PSAs) linked to highly popular television programming, including Soul City's "infotainment" initiatives and in collaboration with national media organisations; (2) social media, via platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat; (3) community radio in each province; (4) public events, specifically, the global 16 Days of Activism for No Violence against Women and Children campaign and National Child Protection Week, both led by the South African government; (5) youth action, through song competitions, creative arts, the formation of change agent teams or working with existing teams (e.g., loveLife peer educator teams), and social media; and (6) print materials, such as billboards, bumper stickers or posters with the theme/slogan, and textiles, such as t-shirts, hats, rubber bracelets and reusable bags.

Sample activities to implement this phase include: (1) coordinating the launch of the overall campaign with media and events, which could include a large launch day music concert with celebrity appearances; (2) incorporating this theme in the DSD-sponsored 16 Days of Activism and National Child Protection Week annual campaign; (3) developing radio segments or PSAs that can be adapted and translated by community radio stations; (4) holding a contest among high schools, technical schools, and colleges to develop a campaign logo; (5) holding a contest to develop theme music with the winner recording at a major studio with a known musical artist (e.g., Mafikizolo, Mi Casa, Miss Lira, Zahara); (6) with respect to community mobilisation, providing materials and training to new or existing teams or groups; and (7) launching a national, celebrity-driven social media campaign with designated hashtags. Recent successful examples include #62milliongirls and #ALSicebucketchallenge.

Phase two: Initiating individual change

While phase one focuses on awareness, motivation and ideational change regarding violence against children, phase two moves the change process forward by linking these changes to actions. Thus the overall phase two objective is to provide specific message instruction concerning alternatives to the use of violence, per the change mechanisms from social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001, 1986) and diffusion of innovations (Rogers, 1995), and to address gaps in personal knowledge and self-efficacy identified through our conduct of formative research. Following the theoretical logic and formative input, the authors determined that phase two objectives would best be accomplished through a continuation of the mass media messages combined with targeted and culturally tailored media outputs (e.g., soapies, community radio, community theatre, print materials, and community action teams) that help people learn how to implement behaviour change in their real-world situations. Phase two activities are directed to parents, teachers, and youth.

Supported by social cognitive and diffusion of innovations theories, the focus of messages in this second phase is on social models, skills and confidence building. For parents, this part of the campaign includes models for how to encourage and maintain good behaviour in children without use of violence, and alternatives for handling family conflicts without violence. Similarly, teachers will see behavioural models of non-violent classroom control. For youth, the messages may be more complex. To mitigate bullying, youth will see models of how to intervene safely, as seen, for example, in programs like Breakthrough's Bell Bajao! (meaning "ring the bell" in Hindi) multimedia campaign in India (Silliman, n.d.). For youth, the strategy is to present examples of how to earn respect, and to have influence in their communities and schools without violence.

This phase would be implemented (over an estimated time of 18-months) through multiple channels, in collaboration with local NGOs, social services and health care providers, and high school or college theater/social justice programs, such as the Drama for Life programme at University of the Witwatersrand. Service providers such as the Teddy Bear Clinic may have existing parent training materials that could be employed to disseminate specific information on the prevention of violence against children. Sample activities in this phase could include: (1) developing and broadcasting content-appropriate soapies; (2) collaborating with national and community radio to participate in coordinated, tailored programming; (3) engaging youth through social media to promote and disseminate specific messages about how to reduce violence against children, and engaging performing arts and theater groups for the same purpose; (4) developing street theater productions to model solutions and raise awareness (e.g., City at Peace model in the United States); and (5) developing an action plan and materials with guidance on violence against children behaviour change for community action teams, and for distribution via social services and health care providers. The PSAs with the primary campaign theme would be maintained for continuing reinforcement.

Phase three: Engage social support systems

Phase two focused on the dissemination of models and guides for individual behaviour change supported by broad campaign themes. However, for individuals to actually make changes in behaviour, additional social facilitators are often necessary. Thus the objective of the third phase is to facilitate adoption of the behaviour change through the engagement of social support, using group and social mobilisation strategies. Following social support theory change mechanisms (House, 1981; Berkman & Glass, 2000), the authors, with stakeholder input, determined that this objective is most effectively accomplished through the use of community action teams, support from community leaders, youth peer action, teacher training, teacher support networks, and parent groups. Target audiences include parents, teachers, youth, traditional and faith leaders. Phase three is proposed to last one year, overlapping with the last six months of phase two.

The focus of messages in this phase is on social reinforcement for behaviour change. For example, parents' motivation to change would be strengthened by support from other parents and traditional or faith leaders, reinforcing the message that behaviour change garners approval, and that there are social support systems that can provide advice on how to implement and maintain change. In an interpersonal, concrete way, this also can help reinforce the reduction of violence as normative. Teachers will benefit from support as well, coming from other teachers and educational administrators. Behaviour change among youth is facilitated by support from adults in their social and family networks and from peers, though it has been well documented that social support has to be engaged carefully with adolescents (Reininger, Perez, Aguirre Flores, Chen, & Rahbar, 2012), as it can have both positive and negative effects.

Sample activities and communication channels to implement this phase include: (1) developing and broadcasting of new soapies focusing on social support themes, and radio programming (regional, community radio) that, for example, features a school that changes its approach to discipline, the way in which its teachers are supported by their colleagues and school administrators, and the positive outcomes that result; (2) organising community-based activities and support groups for parents hosted by faith organisations, civic organisations, and social services; (3) working with local and national journalists to foreground the issue on the national agenda, through special editions and op-ed features that highlight resources available for parents, youth, and others; (4) generating social media activities with the purpose of building social support for behaviour change; and (5) continued distribution of print materials (behaviour change guidance) through social services and health care providers as a means of reinforcement. For youth, the interpersonal activities could be organised through school clubs, civic organisations, and sports and arts activities. For teachers, such activities could be organised through teachers unions or at school or district levels. Again, PSAs with the primary campaign theme would be continued for ongoing reinforcement.

Phase four: Facilitate sustained change

The key objective of the fourth phase (estimated implementation of one year overlapping with the last six months of phase three) is to facilitate maintenance of the behaviour change by advocating for resources and services through, for example, law enforcement, social services, school-based services, and youth gang interventions. Maintenance is typically the last stage of change processes outlined, for example, in the trans-theoretical model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983; Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2002). The authors, with stakeholders' review in South Africa, concluded that the fourth objective is best accomplished through media advocacy (Dorfman & Krasnow, 2014; Wallack, 1994), youth action, and community-level engagement, and that it will require the long-term allocation of resources. Key target audiences are the media, policy leaders and decision-makers.

The focus of messages in this phase is advocacy for increased attention and resources allotted to the kinds of services that are necessary to support and sustain behaviour changes made by individuals. These services include child protection, family counseling, and law enforcement. The messages should center on the idea that movement forward cannot take place without everyone on board (a theme underscored in stakeholder input), and that policies are not enough without the capacity to carry them out.

Sample activities and channels to implement this phase include: (1) developing and publishing opinion pieces for broadcast and print media; (2) supporting radio programming that highlights capacity and resource needs; (3) engaging social media to create demand for better services and awareness of the service gaps; (4) mobilising community and youth groups to stage events and speak before policymaking bodies and individual stakeholders to advocate for and influence relevant policymaking; and (5) continuing television PSAs carrying the primary campaign theme, at selected intervals for reinforcement.

Campaign outcomes and impacts: Outline of monitoring and evaluation

In general, monitoring and evaluation would entail collaboration with a university or research institution (e.g., the University of Cape Town's Children's Institute) for the conduct of a baseline survey (national sample) prior to the campaign, in order to assess: (1) how violence against children is defined; (2) self-reported behaviour; (3) level of intent to change violence against children; (4) level of concern about violence against children; (5) awareness of or involvement with any community mobilisation activities; and (6) individual as well as collective efficacy with respect to changing cultural norms and perceptions that support violence against children. Once the campaign is initiated, follow-up surveys, with measures of campaign activity exposure, would be implemented at six months and one year, followed by two additional one-year follow-ups. The goal of follow-up data collection would be to evaluate change in these same dimensions, moderated by measures of campaign reach - the degree to which messages and activities were received by/involved participation of target audience members.

In each phase, monitoring would focus on assessment of reach; for example, the recording of activities implemented and programs aired, and tracking, by phase, the number of participants in activities as well as materials (e.g., posters, op-ed pieces) distributed or published. If possible, focus groups should be conducted with a sample of parents, youth, teachers, and practitioners to obtain more extensive information on adoption of the theme, attitude and behaviour change, and on barriers and facilitators of change.

6. Conclusions and practical implications

The proposed communication strategy is an attempt to develop a grounded and theory-based plan for engaging in a phased behaviour change promotion effort, using multiple communication channels tailored to a national and local context. It is also an attempt to develop a strategy with a social-ecological orientation, in which the factors influencing behaviour change are understood to occur, and interact, at multiple levels, from the individual out to the social environment.

Our research began with the premise that mediated communication campaigns aimed at addressing social/health problems, such as the societal problem of violence against children, are often not optimally tailored to the complex of factors facilitating violence in the local or regional setting, are not tied to a theory-informed model of change, and are not comprehensively evaluated. In the hypothetical strategy outlined above, we have made a concerted effort to develop a coherent approach that includes these often-missing elements, while at the same time being mindful of resource constraints. It is our hope that the strategy provides a model that can help to fill gaps in existing practice with respect to reducing violence against children.

Implementation and replication

The strategy is oriented to a South African context. However, the basic framework, process, and at least some of the content, may have relevance for the development of campaigns in other countries. Key replicable elements of the strategy could include the staged process, the logic behind that process, and the theoretical justification. In terms of content, replicable elements could include the general strategy of branding a reduction of violence as a focus of national progress, the movement from awareness and motivation to specific social support mechanisms for effecting behaviour change, and the targeting of factors within the social environment (e.g., access to and quality of services, training, implementation of protective legal frameworks that may already be in place) that need to change in order to facilitate individual and institutional change.

Limitations and key features of the proposed strategy

It is a limitation of the work presented here that, because of the time and resources available to conduct the formative research and develop a strategy, we were not able to address all necessary issues. We collected data regarding normative definitions of violence, and we included in the communication strategy elements that are intended to promote change in the prevalence of attitudes accepting harsh physical discipline of children (at home and at school), as well as norms for masculinity in the South African context that foster violence. The strategy seeks to address awareness gaps about the negative outcomes that can occur by these attitudes and practices. Similarly, we sought to address prevalent attitudes and expectations about the "normality" of community violence to which children are exposed, as perpetrators and victims. The normalisation of violence was one of the themes that arose frequently in our formative research, often linked to disruptions in family structure and the legacy of apartheid.

In connecting the various campaign activities to the theme of a South Africa moving beyond that legacy, we also addressed, to some degree, normative definitions regarding a "good child" - the teleology of childrearing. The communication campaign outlined herein takes on that issue by disseminating, through campaign branding, new expectations and norms regarding the level of violence acceptable for children within a changing South Africa. For example, in a township historically plagued by community and family violence, we heard from respondents that violence was understood as the means to power and access to resources. Thus, raising a child who understands that role of violence and can function accordingly might have been viewed as maintaining a positive behavior. In this campaign, we aim to alter this by linking personal and societal progress to a change in that kind of belief and associated childrearing goals, so that an attitudinal or behavioral effect is achieved because such change is perceived as a valued outcome.

However, because of resource and time constraints, we were not able to address some of the other aspects of violence against children specific to the South African context that did arise in the formative research. Our suggested campaign does not, for example, address violence against migrant children, against children who are victims of HIV/AIDS (directly, or as orphans), against disabled children, or against children with certain physical conditions such as albinism. We did also not include campaign components addressing certain gender-based violence practices, such as virginity testing. These issues could perhaps best be addressed by focused campaigns rather than the broader effort proposed in this article.

References

Bandura, A. (1986). Socialfoundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.L1 [ Links ]

Berkman, L. F., & Glass, T. (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In L. F. Berkman, & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social epidemiology (pp. 137-173). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bernard, H. R. (2011). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed.). Lanham, MD: Altamira Press. [ Links ]

Bott, S. (2013). From research to action: Advancing prevention and response to violence against children:Report on the Global Violence against Children Meeting. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/SwazilandGlobalVACMeetingReport.pdf

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Burton, P. (2012). Country assessment on youth violence, policy and programmes in South Africa. Washington, DC: Social Development Department, World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2012/06/16461732/country-assessment-youth-violence-policy-programmes-south-africa [ Links ]

Burton, P., & Leoschut, L. (2013). School violence in South Africa: Results of the 2012 national school violence study. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cjcp.org.za/uploads/2/7/8/4/27845461/monograph12-school-violence-in-south-africa.pdf [ Links ]

BusinessTech. (2015, June 22). South Africa is the second worst country in the world for gun deaths. Retrieved from http://businesstech.co.za/news/government/91284/south-africa-is-the-second-worstcountry-for-gun-deaths-in-the-world/

Chan, M. (2013). Linking child survival and child development for health, equity, and sustainable development. The Lancet, 381(9877), 1514-1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60944-7 [ Links ]

Curran, E., & Bonthuys, E. (2004). Customary law and domestic violence in rural South African communities. Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Retrieved from http://www.csvr.org.za/wits/papers/papclaw.htm [ Links ]

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development. (2014, December 8). Keynote address by the Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, the Hon. John Jeffery, MP, at 4th African Conference on Sexual and Gender Based Violence. Retrieved from http://www.jusuce.gov.za/rnspeeches/2014/20141208GenderSummit.htm l#sthash.c4ClyFl8.dpuf

Department of Social Development (DSD). (2014). South African integrated programme of action addressing violence against women and children (2013-2018). Pretoria. Retrieved from http://www.dsd.gov.za

DSD, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities (DWCPD), & UNICEF. (2012). Violence against children in South Africa. Pretoria. Retrieved from http://www.cjcp.org.za/uploads/2/7/8/4/27845461/vacfinalsummarylowres.pdf

Dorfman, L., & Krasnow, I. D. (2014). Public health and media advocacy. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 293-306. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182503 [ Links ]

Edberg, M., Shaikh, H., Thurman, S., & Rimal, R. (2015). Background literature on violence against children in South Africa: Foundationfor aphased communications for development (C4D) strategy. Washington, DC: Center for Social Well-Being and Development, for UNICEF South Africa. [ Links ]

Edberg, M. (2013). Essentials of health, culture and diversity: Understanding people, reducing disparities. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. [ Links ]

Edberg, M., Chambers, C., & Shaw, D. (2011). The situation analysis of children and women in Belize 2011: An ecological review. Government of Belize and UNICEF Belize. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/sitan/files/SitAn_Belize_July_2011.pdf

Evans, W. D., Longfield, K., Shekhar, N., Rabemanatsoa, A., Snider, J., & Reerink, I. (2011). Social marketing and condom promotion in Madagascar: A case study in brand equity research. In R. Obregon, & S. Waisboard (Eds.), The handbook of global health communication (pp. 330-347). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Fegert, J., & Stötzel, M. (2016). Child protection: A universal concern and a permanent challenge in the field of child and adolescent mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0106-7 [ Links ]

Fehling, M., Nelson, B. D., & Venkatapuram, S. (2013). Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: A literature review. Global Public Health, 8(10), 1109-1122. https://doi.org /10.1080/17441692.2013.845676 [ Links ]

Fulu, E., Kerr-Wilson, A., & Lang, J. (2014). What works to prevent violence against women and girls? Evidence review of interventions to prevent violence against women and girls. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/337615/evidence-review-interventions-F.pdf

Gould, C. (2014, September 17). Comment: Why is crime and violence so high in South Africa? Retrieved from https://africacheck.org/2014/09/17/comment-why-is-crime-and-violence-so-high-in-south-africa-2/

Graham, L., Bruce, D., & Perold, H. (2010). Ending the age of marginal majority - an exploration of strategies to overcome youth exclusion, vulnerability and violence in Southern Africa. Retrieved from http://www.southernafricatrust.org/docs/YouthviolencecivicengagementSADC2010-Full.pdf

Hecht, M. L., & Lee, J. K. (2008). Branding through cultural grounding: The Keepin' it REAL curriculum. In W.D. Evans, & G. Hastings (Eds.), Public health branding: Applying marketing for social change (pp. 161-179). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hillis, S. D., Mercy, J. A., Saul, J., Gleckel, J., Abad, N., & Kress, H. (2015). THRIVES: A global technical package to prevent violence against children. Atlanta: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [ Links ]

House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Knerr, W., Gardner, F., & Cluver, L. (2011). Parenting and the prevention of child maltreatment in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of interventions and a discussion of prevention of the risks of future violent behaviour among boys. Pretoria: Sexual Violence Research Initiative, Medical Research Council. Retrieved from http://www.svri.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2016-04-13/parenting.pdf [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Roberto, N., & Lee, N. (2002). Social marketing: Improving the quality of life (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Landers, C. (2013). Preventing and responding to violence, abuse, and neglect in early childhood - a technical background document. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/protection/files/Report_on_preventing_and_responding_to _violence_in_early_childhood_2013_Cassie_Landers.pdf

Landis, D., Williamson, K., Fry, D., & Stark, L. (2013). Measuring violence against children in humanitarian settings: A scoping exercise of methods and tools. New York and London: Child Protection in Crisis (CPC) Network and Save the Children UK. [ Links ]

Mathews, S., Abrahams, N., Jewkes, R., Martin, L. J., & Lombard, C. (2012). Child homicide patterns in South Africa: Is there a link to child abuse? South African Medical Research Council Research Brief. Retrieved from http://www.mrc.ac.za/policybriefs/_childhomicide.pdf

Mathews, S., Jamieson, L., Lake, L. & Smith, C. (Eds.). (2014). South African child gauge 2014. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. Retrieved from http://www.ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/general/gauge2014/ChildGauge2014.pdf

Nicolson, G. (2015, July 13). Analysis: The gruesome truth about child deaths in South Africa. Daily Maverick. Retrieved from http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2015-07-13-analysis-the-gruesome-truth-about-child-deaths-in-south-africa/#.Vawx9mC3nar

Peltzer, K., & Chirinda, W. (2014). Access to opportunities and the Lovelife programme among youth in South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa 23(1), 77-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2013.10820596 [ Links ]

Pinheiro, P. S. (2006). World report on violence against children. Geneva: UNICEF. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/lac/fulltex%283%29.pdf [ Links ]

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390-395. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.51.3.390 [ Links ]

Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., & Evers, K. E. (2002). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), Health behavior and health education (3rd ed.). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Promundo. (2012). Engaging men to prevent gender-based violence: A multi-country intervention and impact evaluation study. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://promundoglobal.org/resources/engaging-men-to-prevent-gender-based-violence-a-multi-country-intervention-and-impact-evaluation-study/

Proudlock, P. (Ed.) (2014). South Africa's progress in realising children's rights: A law review. Cape Town: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, and Save the Children South Africa. Retrieved from http://ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/researchreports/2014/Realisingchildrensrightsl awreview2014.pdf [ Links ]

Reininger, B. M., Perez, A., Aguirre Flores, M. I., Chen, Z., & Rahbar, M. H. (2012). Perceptions of social support, empowerment, and youth risk behaviors. Journal of Primary Prevention, 33(1): 33-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-012-0260-5 [ Links ]

Richter, L. M., & Dawes, A. R. L. (2008). Child abuse in South Africa: Rights and wrongs. Child Abuse Review, 17, 79-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1004 [ Links ]

Richter, L., Komárek, A., Desmond, C., Celentano, D., Morin, S., Sweat, M., ... Coates, T. (2014). Reported physical and sexual abuse in childhood and adult HIV risk behaviour in three African countries: Findings from Project Accept (HPTN-043). AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 381-389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0439-7 [ Links ]

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Silliman, J. (n.d.). Breakthrough's Bell Bajao! A campaign to bring domestic violence to a halt. Retrieved from http://www.breakthrough.tv

Sonke Gender Justice. (n.d.). Children's rights and positive parenting (CRPP)portfolio. Retrieved from http://www.genderjustice.org.za

Sood, S. (2015). Violence against children (VAC) - a systematic review of C4D approaches. Retrieved from https://www.nationalacademies.org

Soul City Institute. (n.d.). Soul Buddyz series. Retrieved from http://www.soulcity.org.za/research/evaluations/series/soul-buddyz-series

Soul City Institute. (2007). A summary report of the research by Markdata October 2007 - HIV / AIDS impacts of Soul City Series 7. Retrieved from http://www.soulcity.org.za/research/evaluations/series/soul-city/soul-city-its-real-evaluation-report-2007/evaluation-report-2007

Soul City Institute. (2011). Kwanda report 2011. Retrieved from http://www.soulcity.org.za/research/evaluations/kwanda/Kwanda%20Report.pdf/view

Soul City Institute. (2016). Evaluations of the different Soul City programmes. Retrieved from http://www.soulcity.org.za/research/evaluations

Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and maintaining healthy environments - toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist, 47(1), 6-22. https://doi.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.47.L6 [ Links ]

Stokols, D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10, 282-298. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282 [ Links ]

The African Child Policy Forum. (2014). The African report on violence against children. Addis Ababa. Retrieved from http://srsg.violenceagainstchildren.org/sites/default/files/publications_final/africanreportonvac/africanreportonviolenceagainstchildren2014.pdf

UBS Optimus Foundation & World Health Organisation (WHO). (2013). ECD+ workshop preceding the WHO's 6th milestones in the global campaign for violence prevention meeting. Retrieved from http://www.who.int

UNICEF. (n.d.). MODULE 1: Understanding the social ecological model (SEM) and communication for development (C4D). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org

UNICEF. (2014). Hidden in plain sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/publications/index74865.html

UNICEF. (2015). A post-2015 world fit for children. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/agenda2030/files/P2015issuebriefset.pdf

University of Cape Town (UCT). (n.d.). Towards a more comprehensive understanding of the direct and indirect determinants of violence against children in South Africa with a view to enhancing violence prevention: Critical literature review. Unpublished manuscript. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

UCT. (2014). Preventing violence against children: Break the intergenerational cycle. Press release. Retrieved from https://www.uct.ac.za/usr/press/2014/Preventing%20violence%20agai nst%20children.pdf

UN. (2014). The road to dignity by 2030: Ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/reports/SGSynthesisRepor RoadtoDignityby2030.pdf

UN Development Programme (UNDP). (2011). Communication for development - strengthening the effectiveness of the United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/democratic-governance/civicengagement/c4d-effectivenessofun.html

UN Economic and Social Council (UN ECOSOC). (2008). UNICEF child protection strategy. E/ICEF/2008/5/Rev.1. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/protection/CP_Strategy_English(1).pdf

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USCDC). (n.d.). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html

Usdin, S., Scheepers, E., Goldstein, S., & Japhet, G. (2005). Achieving social change on gender-based violence: A report on the impact evaluation of Soul City's fourth series. Social Science & Medicine, 61(11), 2434-2445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.035 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, A., Dawes, A., & Ward, C. (2012). The development of youth violence: An ecological understanding. In C. Ward, A. Van der Merwe, & A. Dawes (Eds.), Youth violence: Sources and solutions in South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, J. M., & Makoae, M. (2014). The prevention of violence against children: Creating a common understanding. In S. Mathews, L. Jamieson, L. Lake, & C. Smith, (Eds.). South African child gauge 2014 (pp. 35-42). Cape Town: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282769760_The_prevention_o f_violence_against_children [ Links ]

Wallack,L.(1994).Media advocacy:A strategy for empowering people and communities.Journal of Public Health, 15(4), 420-436. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819602300303 [ Links ]

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2002). World report on violence and health: Summary. Geneva. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/summary_en.pdf

WHO. (2012). Sexual violence - understanding and addressing violence against women. Information Sheet WHO/RHR/12.37. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/rhr12_37/en

WHO. (2013). European report on preventing child maltreatment. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0019/217018/European-Report-on-Preventing-Child-Maltreatment.pdf_?ua=1

Key informant interviews (conducted via Skype or telephone)

Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention interviewee, Cape Town, 20 August 2015 Childline South Africa interviewee, Durban, 26 August 2015

Child Rights and Positive Parenting Portfolio and MenCare Global Fatherhood Campaign interviewee, Sonke Gender Justice, Johannesburg, 24 August 2015

Children's Radio Foundation interviewee, Cape Town, 31 July 2015

Directorate of Social Cohesion and Gender Equity in Education interviewee, Department of Basic Education, Pretoria, 13 August 2015

Psychology Department interviewee, University of Cape Town, 27 August 2015 Radio 2000 interviewee, Johannesburg, 4 August 2015

Soul City Institute for Health and Development Communication interviewee, Johannesburg, 17 August 2015

Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children interviewee, Johannesburg, 5 August 2015

Focus group discussions (recruited via convenience sampling). All focus groups conducted at the facilities of JDI Research in Johannesburg

Parents focus group, 31 August 2015

Practitioners focus group (e.g., police officers, social workers, NGO personnel), 1 September 2015