Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.26 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2077-4907/2022/ldd.v26.12

ARTICLES

Different cities, different property-tax-rate regimes: Is it fair in an open and democratic society?

Fanie Van ZylI; Carika FritzII

IProfessor, Department of Mercantile Law, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Research Fellow, African Tax Institute, University of Pretoria, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8512-7734

IIAssociate Professor, School of Law, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3995-6646

ABSTRACT

Differentiation does not automatically mean that a person's right to equality has been infringed on. Thus, the mere fact that taxpayers are subject to different property tax rates in South Africa depending on the municipality in which the property falls does not necessarily result in an infringement of section 9 of the Constitution: a specific analysis is required in order to determine the constitutionality thereof. In this article, we examine whether the different rates applicable to properties based on where the property is situated are constitutionally sound vis-à-vis the right to equality. In order to do so, we compare the property tax rates and rebates that apply in respect of residential property in the capital cities of the nine provinces in South Africa. The first part of the article considers the general approach adopted by the courts in establishing whether section 9 of the Constitution has been violated. The second part discusses the legislative framework of property tax, after which the equality enquiry is conducted on the differentiation that occurs in regard to property situated in different municipalities. Lastly, we offer some recommendations in our closing remarks.

Keywords: Equality; property tax; unfair discrimination; tax rates; geographical location

1 INTRODUCTION

Section 9 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution) provides for the right to equality, with subsection 9(1) specifically declaring that "[e]veryone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law". However, in order to afford "the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms", as envisaged in subsection 9(2) of the Constitution, equality cannot simply mean that everyone should be treated identically.2 Rather, "things that are alike should be treated alike, while things that are unalike should be treated unalike in proportion to their unalikeness".3 As such, the right to equality is concerned with substantive equality,4 which necessitates establishing the impact of a specific differentiation on a case-by-case basis.5

From this and other relevant case law,6 it is clear that differentiation does not automatically mean that a person's right to equality has been infringed on. Thus, the mere fact that taxpayers are subject to different property tax rates in South Africa depending on the municipality in which the property falls does not necessarily result in an infringement of section 9 of the Constitution: a specific analysis is required in order to determine the constitutionality thereof.

2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVE, METHODOLOGY AND LIMITATIONS

This article seeks to determine whether the different rates applicable to properties based on where the property is situated are constitutionally sound vis-à-vis the right to equality. For this purpose, we first analyse documents and evaluate the courts' approach in interpreting the right to equality. Thereafter, we apply this approach to the situation where different rates on property are applied in South Africa dependent on the municipality where the property is located. The research method adopted is a critical textual analysis both of provisions in the Constitution and other relevant legislation and of reported cases, published articles, and relevant textbooks.

This article has three parts. To examine whether the application of differing rates to properties depending on their location is an unreasonable and unjustifiable limitation on the right to equality, the first part considers the general approach adopted by the courts in establishing whether section 9 of the Constitution has been violated and how this approach was reflected in a revenue-related matter in City Council of Pretoria v Walker.7 While the concept of "the right to equality" has, since the judgement in City Council of Pretoria v Walker, undergone scrutiny by the South African courts,8 the judgement in this case remains the only one where the right to equality has been considered in the context of fiscal matters; as such, the constitutional enquiry in this article draws mainly on the principles laid out in the Walker case. The second part of this article discusses the legislative framework of property tax, after which the equality enquiry is conducted on the differentiation that occurs when property is situated in different municipalities. Lastly, we offer some recommendations in our closing remarks.

This article does not consider in detail whether the different rates that apply in a municipality in relation to various categories9 of property would pass muster in constitutional scrutiny as regards the right to equality in section 9 of the Constitution. Also, this article does not consider section 9(4) of the Constitution, given that the latter relates to unfair discrimination between persons and is consequently not relevant to the purposes of this article.

3 RIGHT TO EQUALITY

3.1 Equality enquiry

Harksen v Lane established the test, comprising two legs, to determine whether section 9 of the Constitution has been violated. As differentiation is central to an equity investigation,10 both legs require that there be differentiation. The first leg stipulates that where the differentiation lacks a legitimate and rational government purpose - for instance, where it is irrational or arbitrary - then the right to equality is violated.11 The test for rationality has been described as follows:

Rationality review is concerned with the evaluation of a relationship between means and ends: the relationship, connection or link (as it is variously referred to) between the means employed to achieve a particular purpose on the one hand, and the purpose or end itself on the other. The aim of the evaluation of the relationship is not to determine whether some means will achieve the purpose better than others but only whether the means employed are rationally related to the purpose for which the power was conferred.12

Even if there is a legitimate and rational government purpose associated with the differentiation, the right to equality could still be infringed in terms of the second leg. This second leg considers whether the differentiation constitutes discrimination. As section 9(3) prohibits unfair discrimination, and not merely discrimination, this second leg requires one first to identify whether there is discrimination and then to determine whether the identified discrimination is unfair.13

For differentiation to constitute discrimination, it must either be on one of the grounds listed in section 9(3) of the Constitution or on an analogous ground. Accordingly, if the basis for differentiation is "race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth", it would be discrimination on a listed ground. In such an instance, a presumption of unfairness applies.14 If the basis for discrimination is not one of the grounds listed in section 9(3) of the Constitution, it would still be discrimination if the effect of the differentiation is to "[treat] persons differently in a way which impairs their fundamental dignity as human beings".15 An impairment of human dignity occurs through the act of not recognising an individual's equal worth as a human being, regardless of the individual differences.16 In Khosa v Minister of Social Development, the court ruled that the augmentation of an existing disadvantage such as poverty constitutes disregard for equal concern and respect.17 Maseka and Chasakara argue that equality is absent when a material disadvantage is present.18 After establishing that discrimination based on equality is present, the complainant must then prove that this discrimination is unfair.

Unfairness relates to the impact of the discrimination on the complainant and persons who are similarly situated.19 To establish the impact of the discrimination, one must consider if the complainant has been disadvantaged in the past, if the discrimination is based on a listed ground, the overall purpose of the discriminatory practice, and whether the complainant's dignity has been impaired.20 Although the court in Harksen v Lane established the "dignity" test as an objective test, an enquiry into the impairment of the dignity of a person is rather subjective and must be considered on a case-by-case basis. We argue that the enquiry does not end with the personal circumstances of the person whose rights are impaired: the ripple-effect that the discrimination has on persons dependent on the person whose rights are impaired should also be considered.

The following example illustrates our argument. The municipality imposes penalties and interest on property taxes in arrears on A's account because A's property is situated in an affluent neighbourhood. In the case of B, no penalties or interest are imposed because B's property is situated in a slum. A's property is a business that provides employment to three people. The three employees are the breadwinners of their families. The interest and penalties have the result that A must lay off at least two employees. In contrast, B lives alone, employs no one, and nobody is dependent on B's income.

Albertyn argues that employment status, financial hardship, poverty and geographical location all fall under the ambit of human dignity.21 Goldswain supports this view, and adds that it resonates with the principles of ubuntu.22 Accordingly, the ripple-effect of the additional penalties and interest imposed on A affects the human dignity of persons dependent on A's financial well-being. It thus can be argued that the differentiation between A and B affects the human dignity of human beings and potentially results in unfair discrimination.

The ripple-effect of taxes, tax penalties and interest on unpaid taxes was considered in Nondabula v Commissioner SARS, although not in the context of unfair discrimination.23In this case, the court considered the suspension of the "pay-now-argue-later" principle, taking into account the ripple-effect that the principle has on persons dependent on the taxpayer for their livelihoods.24 Of course, in the context of unfair discrimination, our courts have not considered the ripple-effect, as we explain above. However, Maseka and Chasakara's precept - that where a material disadvantage is present, equality is absent - holds true that where differentiation results in a material disadvantage to persons dependent on the person being differentiated against, a situation which could aggravate a pre-existing disadvantage such as poverty,25 equality is absent.

It is important to remember that once it has been established either that the differentiation does not have a legitimate and rational government purpose (as per the first leg of the section 9 enquiry) or that the discrimination is unfair (as per the second leg of the enquiry), section 36 of the Constitution still has to be considered. Only if it is established that the infringement of section 9 is unreasonable and unjustifiable in an open and democratic society26 would a limiting provision be unconstitutional.

Nonetheless, the question arises that if differentiation occurs without a legitimate and rational government purpose or constitutes unfair discrimination, how could it be reasonable and justifiable in terms of section 36? In this respect, Albertyn recognises that the section 9 enquiry and the section 36 justification may overlap.27 However, she explains that section 9 and section 36 require different considerations.28 The section 9 enquiry involves ameliorating social and economic disadvantages and ensuring that the state treats people equally and with respect.29 In turn, section 36's fairness is measured by applying a proportionality standard where the questions of available resources, administrative capacity, and the existence of less invasive means to reach the objective are considered.30 Despite the different considerations that come to the fore when dealing with section 9 and section 36, the court has, to date, not found any unfair discrimination to be justified in terms of section 36 of the Constitution.31

3.2 Equality enquiry and revenue matters

Although the interpretation of the right to equality in relation to taxes levied at national level and the imposition of municipal property rates is yet to be decided in a reported case, the matter of City Council of Pretoria v Walker provides guidance, as it relates to service levies owed to a city council. In this case, the City Council differentiated between Atteridgeville and Mamelodi, on the one hand, and "old Pretoria", on the other. Atteridgeville and Mamelodi are occupied predominantly by persons perceived to have been disadvantaged by the former apartheid system;32 in contrast, old Pretoria is occupied predominantly by persons perceived as having benefitted from that system.33Importantly, while the issues giving rise to the dispute occurred during the Interim Constitution, the court ruled that, as the provisions in respect of equality in the Interim Constitution and the Constitution are not materially different, the matter was considered in respect of the (final) Constitution.34

The first point of differentiation was that water and electricity levies were imposed in old Pretoria based on consumption, which was measured by installed meters, whilst in Atteridgeville and Mamelodi it was levied at a flat rate per household.35 According to the respondent, the different rates resulted in the residents of old Pretoria subsidising the other areas.36 The second point of differentiation related to selective enforcement, as only the outstanding levies of the old Pretoria residents were enforced.37

Dealing with the first point of differentiation, the court determined that the use of different rates was connected to a legitimate and rational government purpose.38Atteridgeville and Mamelodi did not previously have meters to measure water and electricity consumption, whereas old Pretoria did; as such, the different ways in which water and electricity usage were measured were temporary and intended to ensure continuous services by the City Council until these areas all have the same infrastructure and resources.39

With the first leg of the section 9 enquiry disposed of, the court considered whether the different rates could constitute unfair discrimination. The court highlighted that this leg of section 9 requires one to consider not only whether there is direct discrimination but also what the consequences of the differentiation are.40 The court held that due to apartheid, issues of race and geography were "inextricably linked" and, as such, it rejected Sachs J's view in his minority judgement that this differentiation "was based on 'objectively determinable characteristics of different geographical areas, and not race'".41 Accordingly, treating persons differently based on their geographical location constituted indirect discrimination in this case, as the geographical areas were occupied predominantly by white people in old Pretoria and by other races in Atteridgeville and Mamelodi.42

As the court held the different rates to be discriminatory on the (indirect) basis of race, it had to consider whether the discrimination was unfair. In this regard, the court considered the factors identified in Harksen v Lane. First, it stipulated that, from an economic perspective, the complainant, as a white person, had not been previously disadvantaged;43 in addition, Walker did not aver that he was unable to pay outstanding levies. However, the court recognised that, from a political perspective, the complainant is in a vulnerable position, as he is part of a racial minority.44 Secondly, considering the nature and the purpose of the discriminatory practice, the court held that the Council was obliged to ensure the effective collection of the levies.45 As a temporary measure, the flat-rate system, used previously, was relied on until meters were installed in Atteridgeville and Mamelodi.46 It would have been irrational to extend the flat rate to old Pretoria until the meters were installed in Atteridgeville and Mamelodi, as the court considered the flat-rate measure to be "a crude method of recovering charges" in that it calculates average consumption and does not reflect individual consumption.47 Walker also did not offer an alternative method to calculate levies in the absence of meters. Thus, the court held that the respondent failed to present evidence that he had been adversely affected by the different methods used to ascertain the levies.48 Moreover, the differentiation was as a result of a legitimate and rational government purpose.49

Based on the aforementioned, the court concluded that the respondent's dignity was not impaired.50 As a result, the discrimination was not unfair and, therefore, did not infringe on the respondent's right to equality.51 Consequently, it was not necessary to consider section 36 of the Constitution in this matter. In respect of the enforcement of debt, the court ruled that the City Council's selective enforcement of debts of defaulting residents by way of secretive meetings by Council officials was not based on a rational and coherent policy.52 Consequently, this selective enforcement practice infringed on the right to equality.53 As this practice was not in terms of "law of general application",54 it could not be limited in terms of section 36 of the Constitution.55 Accordingly, the selective enforcement practice was unconstitutional.56

4 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK OF PROPERTY TAX

In the main, taxes in South Africa are levied at national level.57 Apart from funding from national government and consumer charges for service delivery (water and electricity consumption), in accordance with the principle of fiscal decentralisation,58municipalities are empowered to levy and collect taxes at municipal level, inter alia, in the form of property taxes. In the South African context, "property tax" denotes the rates levied on immovable property59 and provides an autonomous source of revenue for municipalities.60 Municipalities are authorised to impose these rates primarily for services delivered (directly or indirectly) by the municipality and, secondarily, for the realisation of socio-economic rights through the provision of service delivery.61However, this levying power is not unfettered, as it is not permitted to be unreasonably and materially detrimental to national economic policies and the mobility of goods, services, capital or labour and economic actions across municipal borders.62

Furthermore, this power must be exercised in line with the adopted rates policy.63 The adopted rates policy refers to a policy that a municipality council must implement64 and which sets out how it levies rates in terms of the Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004 (MPRA). This policy must ensure, inter alia, that persons liable for these rates are treated equally and establish criteria for levies applicable to different categories of property, such as residential, agricultural, industrial and commercial properties.65Generally, the differentiation in the taxing of the various types of properties is rational. In accordance with the MPRA, municipalities across South Africa provide a value reduction of properties for property-tax purposes.66 In addition, indigent property holders, persons dependent on grants or pensions, and the temporarily unemployed may apply for specific rebates. These applications are dealt with on a case-by-case basis. Conversely, commercial and industrial property is, generally, taxed at a higher rate. This can be justified on the grounds that commercial and industrial property makes a large footprint in certain areas and results in higher maintenance costs to the municipality. For example, industrial property usually requires greater water and sewerage infrastructure, railway infrastructure, and wider roads and bridges able to carry large trucks and heavy loads. Yet Bird and Slack argue that, as market value is used to distribute the tax burden fairly, there should be no differentiation between residential property, on the one hand, and industrial or commercial property, on the other.67

That said, Bird, Slack and Tassonyi note that residential properties require services that non-residential properties do not; as a result, residential and non-residential properties must be taxed differently.68 For example, residential properties require recreational parks, hospitals, entertainment, and city beautification. These factors may contribute to the argument that residential properties must be taxed at a higher rate than non-residential properties. Yet commercial and industrial property owners can shift the burden of property tax to consumers by factoring it into the cost of production; in addition, property tax on commercial and industrial property is tax-deductible for income-tax purposes69 - as such, some of the tax is shifted back to national level. Bird and Slack therefore correctly opine that property taxes may be viewed as either equitable and efficient ways of raising revenue, or as regressive and undesirable forms of public finance.70 Whether the flavour is to one's taste depends in large part on one's assumptions, on how the taxes are designed and applied, and on the environment in which the taxes are implemented.71

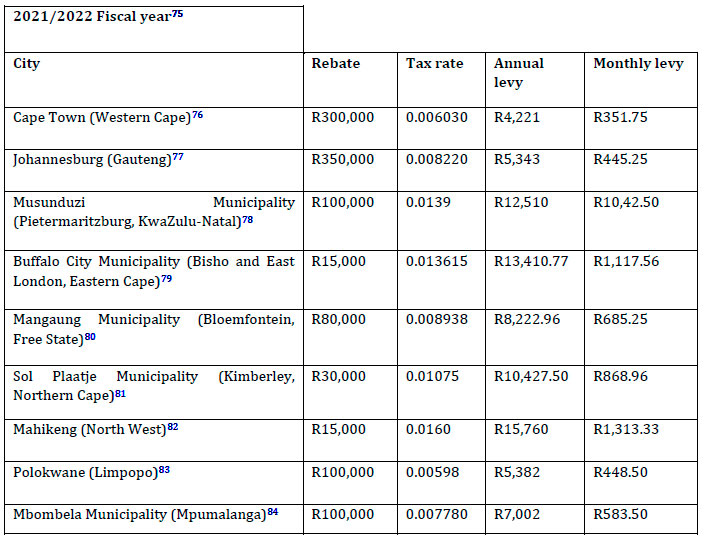

In essence, municipalities have rather broad discretionary powers to levy property tax as long as it complies with the legislative framework discussed above. The effect of these discretionary powers is that the same type of property, for instance residential property, will be subject to different rates depending on the municipality in which the property is located. As argued above, Albertyn points out correctly that a differentiation based on geographical location may affect the human dignity of that person. Such a differentiation may result in an unfair discrimination.72 For the purpose of this study, we highlight the property taxes of a residential property73 with a market value of ZAR 1 million74 in the capital city of each province for the 2021/2022 fiscal year.

In the examples above, the rebates in respect of residential property include the statutory minimum rebate of R15,000 as imposed by the MPRA. While the policy documents that regulate the respective municipalities' property taxes are aligned with the statutory structure of the MPRA, the actual rebates and tax rates of the cities differ significantly.

5 RIGHT TO EQUALITY AND DIFFERENTIAL PROPERTY TAX RATES

To determine whether the different rates applicable to properties based on where they are situated are constitutionally sound vis-à-vis the right to equality, the equality-enquiry test as stipulated in Harksen v Lane is applied below. Accordingly, this section begins by considering the first leg of the enquiry, that is, legitimate and rational government purpose associated with differentiation, and, thereafter, the second leg of the enquiry, that is, unfair discrimination.

5.1 Is there a legitimate and rational government purpose associated with the differentiation?

In general, the purpose of imposing property tax is to fund the expenses that the municipality85 incurs in relation to delivering services86 to the property owners in its territory. Thus, property tax is primarily a source of revenue for municipalities in order to facilitate service delivery.87 As such, property tax rates are determined annually in accordance with budgetary needs.88 Apart from financing public expenditure, taxation, in general, is used to accomplish other objectives. One such objective is the redistribution of resources (by way of realising socio-economic rights), which is vital in South Africa,89 a country with a severely unequal distribution of income, as is apparent from its Gini index of 63 established in 2014.90 While national taxes are best suited for the redistribution of resources, some redistribution takes place at municipal level. This is achieved through the municipality's indigent persons' policies by way of free basic water and electricity and additional property tax rebates.91

As Franzsen indicates, equality is not concerned with taxpayers having the same tax liability or the same tax rate.92 Consequently, Murphy remarks that a differentiation in tax rates may very well lead to fiscal equality.93 This resonates with one of the canons of taxation: the equity principle.94 The equity principle is underpinned by the taxpayer's ability to pay the tax as well as the proportion to which the taxpayer benefits from state service delivery.95 In relation to the first underpinning, people with the same ability to pay should be treated similarly by paying the same amount of tax (horizontal equity),96while people with different economic conditions should be treated differently (vertical equity).97 A natural outflow of taxing according to a person's ability to pay is ensuring an equal distribution of wealth.

Based on this principle, a property that is valued more should attract a higher property-tax liability, so that municipalities can assist in realising the socio-economic rights of their residents.98 However, that does not necessarily mean that higher-value properties that attract higher property taxes get superior service delivery. 99 Moreover, this taxing method relies on the assumption that a person who owns a higher-value property has an income matching that property value. Accordingly, as owners of higher-value properties pay more than owners of lower-value properties, it is clear that property tax accords with taxing according to the taxpayer's perceived ability to pay.

However, the current property tax framework goes beyond the "higher property value attracts higher taxes" method of taxation. The different municipalities in South Africa establish different rates applicable to properties.100 For example, the table above indicates that a property of ZAR 1 million in Cape Town is taxed at a lower rate than a property of ZAR 1 million in Mahikeng. Thus, there is differentiation based on where the property is situated. From City Council of Pretoria v Walker, it is evident that taxing persons differently based on their geographical location should be regarded with circumspection, as it may constitute indirect discrimination.

Property values in different cities differ significantly.101 It is well known that property in Cape Town is valued much higher than in other inland cities.102 For example, a property in Cape Town valued at R1 million is likely to be in the lower spectrum of properties, while a property valued at R1 million in Polokwane is considered to be in the middle to upper spectrum.103 Therefore, cities such as Cape Town can set lower rates because properties are, generally, valued much higher in Cape Town.

However, whilst this is a factor to consider, the circumstances of property owners cannot be ignored when determining the value threshold and tax rates. For instance, in Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality, disabled persons are awarded a percentage rebate on a sliding scale in accordance with their gross income.104 Some property-tax diehards will argue that this amounts to a mixing of income-tax and property-tax principles. Nonetheless, some data show a correlation between rising income levels and reliance on property taxes.105 Ali et al. acknowledge that it is a particular problem for developing countries when the income-earning capacity of property owners is ignored.106 Of course, a revenue-neutral response to higher property values is to reduce the tax rates.107 This is the case in Cape Town, where the lower tax rate should, in principle, equalise the tax burden on high-value properties.

The average income in Johannesburg is much higher than any other city in South Africa,108 and, as such, a higher property tax rate in Johannesburg may be justified. Yet the current property tax rates and rebate that apply in Johannesburg make living in Johannesburg more affordable than in East London or Pietermaritzburg.109 Statistically, the Eastern Cape province has the highest poverty and unemployment rate in South Africa, followed by the Northern Cape.110 The Western Cape and Gauteng are the richest provinces based on per capita income and unemployment.111 Yet property taxes in East London and Kimberley are much higher than in Johannesburg and Cape Town.112 Is there indeed a rational and legitimate government purpose that warrants the high property taxes in East London and Kimberley?

Again, it must be emphasised that the basis for property tax is, essentially, property values. The taxpayer's income should, in principle, not play a decisive role. As we indicated above, however, the ability to pay, at least in South Africa, plays some role in different municipalities' rebate regime. Franzsen and McCluskey support a regime where the ability to pay plays an indirect113 role in setting property tax rates, exemptions, and rebates.114

Bahl et al. point out correctly that horizontal equity and fairness of property taxes can be questioned.115 Municipalities may be best equipped to determine the property-tax rates, thresholds and rebates in their respective municipalities by taking into account the overall tax base in the municipality.116 Generally, there appears to be a legitimate purpose for different property taxes depending on where property is situated. However, considering the misalignment between the different municipalities, as set out above, the rationality of the effect of the different treatment is not so clear. Importantly, Bird and Slack opine that property tax must not result in a distortionary impact on location or land use.117 This is because such differentiation affects location decisions, economic decisions and decisions about the activities to undertake.118 For example, a low property tax in one region may result in that region becoming more densely populated than others.119

This results in greater strain on infrastructure that further impacts on the city's budget requirements. Cities such as Cape Town and Durban attract industries because of their easy access to distribution routes. Mahikeng and Kimberley, in our view, although connected to major roads and rail networks, are not as conveniently located as Cape Town and Durban. A higher property tax in Mahikeng and Kimberley may result in the distortionary impact on location that Bird and Slack warn against.

Yet Bird and Slack highlight that a differentiation in property tax rates is not a deciding factor in determining inequality.120 This is so because in cities where property values are generally higher, a lower tax rate applies, whereas in cities where property values are generally low, a higher tax rate applies.121 This should, in principle, translate into similar effective tax rates in different cities, and essentially, remove any perceived differentiation. The autonomy of a municipality to determine the rates in accordance with property values in that municipality should, essentially, satisfy both the horizontal and vertical equity of the tax system.122 Of course, this argument holds true only where high-property-value cities apply a low rate and low-property-value cities apply a higher rate. Moreover, for this argument to hold true, valuation of property must be done regularly, fairly, and transparently.123

5.2 Does the differentiation amount to unfair discrimination?

Despite our view above that the right to equality is infringed in terms of the first leg, for completeness we also consider the second leg of the equality enquiry. As indicated earlier, this leg requires one to first determine whether the specific differentiation constitutes discrimination before considering whether the discrimination is unfair. Differentiation based on where people stay is not a ground directly listed in section 9(3) of the Constitution. Nonetheless, as transpired in City Council of Pretoria v Walker, race and geographic location can be "inextricably linked". Thus, differentiation based on location does not necessarily fall outside the scope of section 9(3).

As stated earlier, in order to provide service delivery and realise socio-economic rights, municipalities need money. Cities where the demand for socio-economic rights and service delivery is high require more funding than others. In addition, a lack of infrastructure adds to the financial needs of a city. Ahmad et al. opine that it is essential for local governments to set the tax rate to ensure a correspondence between the tax rate and the services provided.124 Accordingly, higher tax rates in some cities can be justified as a means to achieve a rational and legitimate government purpose, that is, expanding service delivery to previously disadvantaged areas.

So, for example, the 100 per cent rebate on rural residential property in the Sol Plaatje Municipality can be justified on the basis that these properties are not connected to the municipal electricity, water and sewerage infrastructure. Similarly, in the Eastern Cape, employed persons who own property valued higher than R15,001 subsidise the large number of unemployed persons125 and owners of properties valued at less than R15,000. In other words, because the Eastern and Northern Cape are stricken by high unemployment and poverty rates,126 those members of society who can afford paying property taxes must pay more taxes as a form of distribution of wealth. This is in line with the equity principle set out above. Yet this argument does not hold, for example, in the case of Pietermaritzburg. However, it can be argued that the R100,000 value threshold in this city serves a similar purpose in keeping to the equity principle. Importantly, the autonomy of municipalities to set rates, thresholds, rebates and exemptions can foster arbitrariness.127 The MPRA in the main requires that municipalities determine rates transparently.

As we canvass some legitimate reasons for the geographical differentiation above, for purposes of this article one would, in accordance with the principles laid out in City Council of Pretoria v Walker, need to establish an inextricable link between the various municipalities and race before it is possible to conclude that there is (indirect) discrimination based on race. In this respect, the Sol Plaatje Municipality has a relatively high property-tax rate, in spite of the fact that the majority of its residents, 61.2 per cent, classified themselves as black in the 2011 census.128 Equally, in the City of Johannesburg, 76.4 per cent classified themselves as black.129 Nonetheless, the City of Johannesburg has a relatively low property-tax rate. It is submitted that further comparisons between race and the property-tax rate would lead to the same result as with the comparison of Sol Plaatje Municipality and City of Johannesburg - no apparent link. This shows that the property-tax rate is determined not in relation to the race of the majority in that municipality but in relation the value of property in the municipality and the infrastructure. Thus, an inextricable link is not as straightforward to establish in relation to property tax as it was in City Council of Pretoria v Walker. This means that the different property rates do not constitute (indirect) discrimination on the grounds of race.

Even though the different rates amongst municipalities are not seen as discrimination that differentiates based on race, if the differentiation has the effect of treating persons differently in a manner that impedes their dignity, it will still amount to discrimination. Here, as argued earlier, we suggest that the ripple-effect of the discrimination on persons dependent on the person who is subject to the differentiation be considered. When a person is paying more in property taxes simply because of the market value, which is dependent on where the property is situated, it could have an impact on, for instance, the number of people she employs (domestic workers and gardeners), which, in turn, could have an impact on the unemployed persons' dignity by, for example, aggravating poverty. Although property tax is, in principle, concerned with property values and not the person or taxpayer, the taxpayer (property owner) is considered when the rates are determined. For example, indigent taxpayers in some cities qualify for additional rebates.

Thus, in our view a case could be made that there is discrimination that affects persons' dignity. However, it might be more difficult to prove this than relying on the first leg of the enquiry and showing that there is no legitimate and rational purpose for the different property rates. This is so because the ripple-effect theory has not been considered in the South African courts in the constitutional context. Even where such an argument succeeds, it should then be established whether the infringement of section 9 of the Constitution is reasonable and justifiable by considering section 36 of the same.

5.3 Section 36 of the Constitution

From the outset, it must be noted that the existing jurisprudence on the interpretation and application of the section 36 limitation clause is limited. The courts spend the bulk of the analysis on the rights allegedly infringed on, while a discussion of the limitation clause is generally brief and confined to a few paragraphs.130 The limitations clause is generally applied with caution.131 The limitations clause gives rise to a two-stage enquiry.132 The first stage considers whether a right has been infringed on. This requires an investigation into the right's limitations and whether the law or action complained against crosses those limits.133 In the current discussion, we have established that a property owner's right to equality is prima facie infringed on by the different property-rates regimes that apply in the different cities. In other words, the right to equality is infringed on based on geographical location. The empowering rates structures of the different municipalities infringe on the right to equality.

Once it has been found that a right has been infringed on, the second stage, which concerns a justification of the limitation, begins.134 In the second stage, two basic requirements must be met. First, the limitation must be in terms of a law of general application, and, secondly, the limitation must be justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom.135 The requirement of a law of general application entails that the limitation must be in terms of law, albeit common law or statutory law,136 and the law must not apply to specific groups of persons only or apply arbitrarily.137 Thus, similarly situated persons should be treated the same.138Furthermore, the limiting law should be accessible and precise.139 Although the respective property-rates regulations apply only to a specific group of persons (property owners), all property owners are subject to property rates that are publicly available and clearly specified. Therefore, these policies constitute law of general application.

Turning to the second requirement, in S v Makwanyane140 Chaskalson explains that a justifiable limitation translates to a series of tests. This includes determining the importance of the limitation in an open democratic society; the nature of the right infringed; the extent and success of the limitation in reaching the objectives of an open and democratic society; and whether the objectives can be achieved by way of a less restrictive means.141 These tests are not a check-list exercise but rather a balancing act142 where the rights of the individual must be weighed against the purpose of the limitation (public policy) and there must exist a valid, rational, and legitimate reason why the values of the limitation outweigh the values of the rights infringed.143Importantly, the criteria of what would be "reasonable and justifiable" differ according to the circumstances in which it is applied.144 Iles points out that the factors listed in section 36 are not a closed list and that other factors may also be considered.145 A consideration of the factors now follows.

In relation to the first factor, the nature of the right, one must consider the particular importance of the right in the constitutional framework.146 As South Africa has a history deeply rooted in racial and class inequality, the right to equality is paramount in ensuring a more substantively equal society.147 The importance of equality in the context of the constitutional framework is highlighted by the fact that achieving equality is one of the founding values of the Constitution.148 From this it is clear that it would be difficult to justify an infringement of this right. When considering the second factor, the limitation must serve a purpose that most people regard as compellingly important.149It must be determined if the purpose or importance of the limitation is consistent with a set of values against which to measure the purpose.150 Then, in terms of the set of values, it must be determined if the purpose of the limitation is sufficiently important or compelling to justify the limitation of a constitutional right.151

In the current study, the rights of a person not be discriminated against because of his or her geographical location must be weighed against the municipality's constitutional duty to obtain funding to provide service delivery and realise the socio-economic rights of the broader community. As we have pointed out above, because of high unemployment and poverty rates and lack of infrastructure, some municipalities require much more funding than others to deliver services and realise the socioeconomic rights of the broader community. As municipal budgets are made up of different items, no data exist that directly link the revenue from property taxes and service delivery or the realisation of socio-economic rights within a particular municipal area. Accordingly, it cannot be determined with accuracy whether the objective -service delivery and the realisation of socio-economic rights - is achieved successfully as a result of the property taxes alone.

The enquiry into the nature and extent of the limitation is a proportionality analysis which entails that the more severe the infringement, the more compelling the purpose must be.152 One must question whether the harm is in proportion to the benefit.153Although the nature and the extent of the limitation on the right should be scrutinised, as opposed to the extent of the limitation on the person whose rights are infringed on,154 we argue that the ripple-effect of the unfair discrimination should be considered. Thus, in order to determine the impact of the limiting provisions, the broader impact should be considered when municipals rates cause unfair discrimination. The section 36(1)(d) factor is closely related to the nature and extent of the limitation, as it deals with the relationship between the limitation and its purpose. Currie and De Waal indicate that, essentially, it means that there should be a good reason for the infringement. As a result, the limitation should serve the purpose it is designed to serve.155 Although municipalities impose property rates for service delivery and realising socio-economic rights,156 which are good reasons, the fact that it is done at different rates does not aid this purpose. This is because, as we have shown, no rational connection can be drawn between the rates per municipality, on the one hand, and the services required and the need to realise socio-economic rights, on the other.

In regard to the last enquiry, it must be determined if any less restrictive method of achieving the overwhelming purpose exists.157 If the same purpose can be achieved by another means which is less invasive or limiting, the limiting law or action is not reasonable and justifiable.158 However, when the court considers the "less restrictive means", it must not obliterate the range of choice to the legislature.159 The court must be careful not to dictate the method to the legislator.160 In the current discussion, it can be argued that a less restrictive method of achieving the objectives is to adopt a unified national property tax rate system so as to ensure that the same category of property of the same value will be subject to the same rebates and the same tax rates in every municipality in South Africa.

While this would remove discrimination based on geographical location, it ignores the fact that the financial outlook of every municipality is different. In Cape Town and Johannesburg, the number of persons who can afford property taxes is much higher than in East London and Kimberley. As the tax base in East London and Kimberley is much smaller, a national uniform tax rate would impact significantly on the revenue of East London and Kimberley. This would result in these two cities being unable to realise socio-economic rights or provide service delivery. Accordingly, other streams of revenue must be considered for them. In these cities, additional funding from the national budget may be required. But this would result again in differentiation when the residents of these geographical areas are subject to additional local taxes to make up for the loss in property taxes created by a national rate system.

For example, at the time of writing, Johannesburg follows a value-base rate for refuse removal. This means that a property owner of a property valued at R5 million pays much more for the refuse removal of a single wheelie bin than a property owner whose property is valued at R1 million. During 2021, the City of Tshwane introduced a compulsory city network charge for being connected to the water grid. This network charge is levied regardless of water consumption. Water consumption exceeding 10kl per month is billed separately. These additional local taxes put a severe strain on the ratepayers' budget.

In addition, for property tax, market value is used to distribute the tax burden. The market values differ significantly in the various geographical areas, as we have pointed out above. As such, a uniform tax rate determined at national level would result in further geographical differentiation. This is because the higher market value in more affluent cities such as Cape Town and Johannesburg would result in these properties attracting a much higher tax burden. This differentiation then results in inequality. Moreover, drawing on the ripple-effect theory that we introduce in this article, this inequality would probably aggravate the poverty of the persons who are dependent on the financial well-being of the ratepayer. Yet Bird and Slack mention that the differentiation caused by the current dispensation is a natural outflow of property tax, the effect of which is of a much smaller magnitude than the impact of property values on capital gains tax and potentially income tax (where rental income is higher for high-value properties).161 Accordingly, a uniform national property rate would not be less restrictive than the perceived discrimination under the existing system of different rates in different geographical areas; rather, it would exacerbate the differentiation.

6 CONCLUSION

Since the promulgation of the Municipal Property Rates Act, municipalities across South Africa adopted property rates policies that are aligned with the requirements of the Act. This is a significant step towards the equitable treatment of property owners in respect of property taxes. However, municipalities still have discretion, based on their budgetary needs, to implement their own rebate and rates system. This results in discrimination based on the geographical location of the property. While the grounds for justification of the differentiation appear reasonable and legitimate, the question that emerges is whether discrimination on the ground of geographical location is at all necessary 26 years into democracy. There is still a huge divide between rich and poor in South Africa. A large number of people still cannot exercise their socio-economic rights. All the cities considered in this research share in this conundrum. Yet specific geographical areas such as the Northern and Eastern Cape seem to host larger concentrations of poor people. Therefore, in cases where municipalities in areas where poverty is more prevalent impose higher property taxes to fund the realisation of socioeconomic rights, the discrimination based on geographical location is not unfair per se. However, this is a dispensation that cannot continue in perpetuity.

Location-based differentiation in property tax is not unique to South Africa. Although it has its drawbacks, the alternative to it that we considered is a uniform rate set at national level - which presents significant problems. First, it interferes with the local government's autonomy to implement a tax regime suitable for that city's needs. This is likely to fall afoul of section 229 of the Constitution which provides for the autonomy of municipal fiscal powers and functions. Secondly, a national uniform rate will likely be either too high or too low for a large number of municipalities. Thirdly, where the uniform rate is set too low, it impacts on the allocation of revenue and will affect municipal budgets negatively. This is probably contrary to sections 214 and 215 of the Constitution. Fourth, the implementation of a uniform rate requires that all the properties in the country must be appraised in a single period. This will be impossible to achieve because there simply are not enough suitably qualified appraisers in the country.162

Fifth, it is unlikely that the national government will review and revise the rates and the valuations regularly. It is well-known that a static tax rate is the downfall of any tax system, including that of property taxes.163 Sixth, a uniform rate affects the decentralisation purpose of property tax and potentially eradicates the accountability of local government. Lastly, the magnitude of the impact of the differentiation caused by a uniform rate is likely to surpass that of different rates based on location.164 For example, the impact on the property owner in Cape Town, where a R1 million property is in the lower spectrum of property values, is much more compared to the owner in Polokwane, where the R1 million property is in the middle to upper spectrum of values.

All things considered, the current dispensation is perhaps less the villain than what our research, at times, portrays. Although we find that the different rates discriminate against persons based on location and that the discrimination is unfair, the alternative of a uniform rate does not remove the perceived discrimination. As the alternative provides no workable solution, we believe that until a workable, less restrictive alternative can be found, the current dispensation can be justified under section 36 of the Constitution.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

The first author conceptualised the article and wrote the part on the legislative framework of property tax, whilst the second wrote the part on the right to equality. Both authors contributed equally to the remainder of the article.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bird RM & Slack E International handbook on land and property taxation Cheltenham: Edward Elgar (2004) [ Links ]

Bird RM, Slack E & Tassonyi A A tale of two taxes: Property reform in Ontario Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2012) [ Links ]

Bird RM & Vaillancourt F (eds) Fiscal decentralisation in developing countries Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1999) [ Links ]

Currie I & De Waal J The Bill of Rights handbook 6th ed Cape Town: Juta (2013) [ Links ]

Davis DM, Cheadle H & Hayson N Fundamental rights in the Constitution: Commentary and cases Cape Town: Juta (1997) [ Links ]

Franzsen R & McCluskey W (eds) Property tax in Africa: Status challenges and prospects Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2017) [ Links ]

Ingram GK & Hong YH Fiscal decentralisation and land policies Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2008) [ Links ]

Meyerson D Rights limited Cape Town: Juta (1997) [ Links ]

Mubangizi J & O'Shea A The protection of human rights in South Africa: A legal and practical guide 2nd ed Cape Town: Juta (2013) [ Links ]

Sieg H Urban economics Princeton: Princeton University Press (2020) [ Links ]

Smith A An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations Vol. 2 London: W Strahan & T Cadell (1776) [ Links ]

Stiglitz JE & Rosengard JK Economics of the public sector 4th ed New York City: WW Norton (2015) [ Links ]

Williams DW & Morse G Davies principles of tax law 4th ed London: Sweet & Maxwell (2000) [ Links ]

Chapters in books

Albertyn C "Equality" in Cheadle MH, Davis DM & Haysom NRL South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights South Africa: LexisNexis (2019)

Albertyn C "Equality" in Cheadle MH, Davis DM & Haysom, NRL South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights South Africa: LexisNexis (2021)

Albertyn C & Goldblatt B "Equality" in Woolman S, Bishop M & Brickhill J (eds) Constitutional law of South Africa 2nd ed Cape Town: Juta (2013)

Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M "Whither the property tax: New perspectives on a fiscal mainstay" in Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M (eds) Challenging the conventional wisdom on the property tax Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2010)

Cheadle H "Limitation of rights" in Cheadle H, Davis DM & Haysom NRL South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights South Africa: LexisNexis (2022)

Murphy J "The constitutional review of taxation" in Jooste R (ed) Revenue law Cape Town: Juta (1995)

Muthitacharoen A & Zodrow GR "The efficiency cost of local property tax" in Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M Challenging the conventional wisdom on the property tax Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2010)

Sheffrin SM "Fairness and market value property taxation" in Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M (eds) Challenging the conventional wisdom on the property tax Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2010)

Woolman S & Botha H "Limitations" in Woolman S et al. (eds) Constitutional law of South Africa 2nd ed Cape Town: Juta (2015)

Youngman JM "Tax on land and buildings" in Thuronyi V Tax law design and drafting Vol. 1 Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (1996)

Zolt EM "Revenue design and taxation" in Moreno-Dodson B and Wodon Q (eds) Public finance for poverty reduction: Concepts and case studies from Africa and Latin America volume 1 Washington, DC: World Bank (2007)

Journal articles

Ahmad E, Brosio G & Pöschl C "Local property taxation and benefits in developing countries: Overcoming political resistance?" 2014 Asia Research Centre Working Paper 1-34

Currie I "Balancing and the limitation of rights in the South African Constitution" (2010) 25(2) Southern African Public Law 408-422

Franzsen RCD "Some questions about the introduction of a land tax in rural areas" (1999) 11(2) South African Mercantile Law Journal 259-267

Franzsen RCD "Property tax: Alive and well and levied in South Africa" (1996) 8(3) SA Mercantile Law Journal 348-365

Goldswain G "Are some taxpayers treated more equally than others? A theoretical analysis to determine the ambit of the constitutional right to equality in South African tax law" (2011) 15(2) Southern African Business Review 1-25

Iles K "A fresh look at limitations: Unpacking section 36" (2007) 23 SAJHR 68-92

Maseka N & Chasakara R "Fishing for equality in marine spatial planning" 2018 JOLGA 52-77

Rautenbach IM "Riglyne om die reg op gelykheid toe te pas" 2012 (9) 2 LitNet Akademies 229-265

Westen P "The empty idea of equality" (1982) 95(3) Harvard Law Review 537-596

Constitutions

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Legislation

Income Tax Act 58 of 1962

Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Case law

Ab v Minister of Social Development 2017 (3) SA 570 (CC)

Chief Lesapo v North West Agricultural Bank 2000 (1) SA 409 (CC)

City Council of Pretoria v Walker 1998 (3) BCLR 257 (CC)

De Lange v Smuts NO 1998 (3) SA 785 (CC)

Democratic Alliance v Minister of Home Affairs and others (48418/2018) [2021] ZAGPPHC 500 (6 August 2021)

De Reuck v Director of Public Prosecutions 2004 (1) SA 406 (CC)

Freedom of Religion South Africa v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and others (Global Initiative to end all Corporal Punishment of Children and others as amici curiae) 2019 (11) BCLR 1321 (CC)

Government of the Republic of South Africa and others v Grootboom and others 2001 (1) SA 46

Harksen v Lane 1997 (11) BCLR 1489 (CC)

Hoffman v South African Airways 2000 (11) BCLR 1211 (CC)

Investigating Directorate: Serious Economic Offences v Hyundai Motor Distributors (Pty) Ltd 2001 (1) SA 545 (CC)

Islamic Unity Convention v Independent Broadcasting Authority 2002 (4) SA 294 (CC)

J v National Director of Public Prosecutions and another (Childline South Africa and Others as Amici Curiae) 2014 (7) BCLR 764 (CC)

Jaftha vSchoeman 2005 (2) SA 140 (CC)

Johncom Media Investments Ltd v M and Others 2009 (8) BCLR 751 (CC)

Jordan and Others v State 2001 (6) SA 642 (CC)

Khosa v Minister of Social Development 2006 (6) SA 505 (CC)

Magajane v Chairperson, North West Gambling Board 2006 (5) SA 250 (CC)

Mail and Guardian Media Ltd and Others v Chipu NO and others 2013 (6) SA 367 (CC)

Manong and associates (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town 2009 (1) SA 644 (EqC)

MEC for Education Kwazulu-Natal v Pillay 2008 (1) SA 474 (CC)

Metcash Trading Ltd v Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service and another 2001 (1) SA) 1109 (CC)

Minister of Finance and another v Van Heerden 2004 (6) SA 121 (CC)

Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie 2006 (1) SA 524 (CC)

Mvumu v Minister of Transport 2011 (5) BCLR 488 (KH)

Naidoo v Minister of Safety and Security and another 2013 (3) SA 486 (LC)

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice 1998 (12) BCLR 1517 (CC)

Nondabula v Commissioner: SARS and another 2018 (3) SA 541 (ECM)

Premier Mpumalanga v Executive Committee of the Association of the Governing Bodies of State-aided Schools, Eastern Transvaal 1999 (2) SA 91 (CC)

President of the Republic of South Africa v Hugo 1997 (4) SA 1 (CC)

Prince v President, Cape Law Society 2002 (2) SA 794 (CC)

Prinsloo v Van der Linde 1997 (3) SA 1012 (CC)

Ramakatsa and Others v Magashule and Others 2013(2) BCLR 202 (CC)

Rates Action Group v City of Cape Town 2004 (12) BCLR 1328 (K)

S v Makwanyane 1995 (3) SA 391

S v Manamela 2000 3 SA 1 (CC)

S v Meaker 1998 (8) BCLR 1038 (W)

S v Zuma and others 1995 (4) SA BCLR 401 (CC)

Social Justice Coalition and others v Minister of Police and others 2019 (4) SA 82 (WCC)

South African Navy and Another v Tebeila Institute of Leadership, Education, Governance and Training [2021] 6 BLLR 555 (SCA)

Zuma v Democratic Alliance 2018 (1) SA 200 (SCA) 674 (CC)

Reports

Ali M, Fjeldstad O & Katera L "Property taxation in developing countries" (2017) 16(1) CMI Brief available at https://www.cmi.no/publications/6167-property-taxation-in-developing-countries (accessed 8 August 2022]

Bird RM & Zolt EM Introduction to tax policy design and development draft prepared for a course on practical issues of tax policy in developing countries Washington, DC: World Bank (2003) available at file:///C:/Users/A0066482/Downloads/Introduction_to_Tax_Policy_Design_and_De.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022]

Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality Property rates policy available at https://www.buffalocity.gov.za/CM/uploads/documents/6503075554036.pdf (accessed 31 January 2022)

City of Cape Town (2020/2021) Property rates (2019) available at https://www.capetown.gov.za/Family%20and%20home/residential-property-and-houses/property-valuations/property-rates (accessed 11 August 2022)

City of Johannesburg (2018/2019) Property rates policy (2018) available at https://www.joburg.org.za/services/Documents/rates%20and%20taxes/Rates%20Policy%202018-19.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

City of Johannesburg 2019/2020 Tariffs (2019) available at https://www.joburg.org.za/documents/Documents/TARIFFS/Tariffs/big%20%20tariff.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

eThekwini Municipality. Tariff tables 2019/2020 (2019) available at https://www.durban.gov.za/storage/Documents/Budget%20Reports/Tariffs/Tariff%20Tables%202019%20-%202020.pdf (accessed 11 August 2022)

Katz Commission of Inquiry into Taxation Third interim report (1995) Mahikeng Municipality 2019/2020 Tariffs (2019) available at https://www.mahikeng.gov.za/download/approved-tariff-schedule-2019-2020/?wpdmdl=12271&refresh=62f122be3381d1659970238 (accessed 8 August 2022)

Mangaung Municipality 2019/2020 Budget (2019) available athttp://www.mangaung.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Budget-MTREF-2017-18-2019-20.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

Mbombela Municipality 2019/2020 Budget (2019) available at https://www.mbombela.gov.za/final%2020192020%20%20detailed%20adjustments%20budget%20report.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

Nelson Mandela Bay Municipal Council 2019/2020 Budget (2019) available at https://www.nelsonmandelabay.gov.za/datarepository/documents/2019-20-budget-report.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

Nelson Mandela Bay Municipal Council Property rates policy (2021) available at https://www.nelsonmandelabay.gov.za/DataRepository/Documents/property-rates-policy-2021-22adopted Hc8Yi.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

Polokwane Municipality 2019/2020 Budget (2019) available at https://www.cdm.org.za/2019-2020-approved-budget/ (accessed 8 August 2022)

Sol Plaatjes Municipality 2019/2020 Budget (2019) available at http://www.solplaatje.org.za/CityManagement/Reporting/AdoptedBudget/Budget%202019-2020.pdf (accessed 8 August 2022)

Internet sources

"The average salaries in 10 major cities across South Africa" Businesstech (24 June 2019) available at https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/325219/the-average-salaries-in-10-major-cities-across-south-africa/ (accessed 8 June 2022) [ Links ]

Property24 "Property trends" (2022) available at www.property24.com/property-trends (accessed 8 June 2022) [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa Community survey (2016) available at http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed 8 April 2020) [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa "Statistics by place - City of Johannesburg" (2011(b)) available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/Ppageid=993&id=city-of-johannesburg-municipality (accessed 16 April 2020) [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa "Statistics by place - Sol Plaatjes" (2011(a)) available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/Ppageid=993&id=sol-plaatjie-municipalit (accessed 16 April 2020) [ Links ]

World Bank "GINI index- South Africa" (2019) available at https://bit.ly/2Vr3gqM (accessed 16 April 2020) [ Links ]

1 The authors thank Prof Riel Franzsen for his invaluable comments on the first draft of this article, which was presented online at the African Tax Research Network Annual Congress in September 2021.

2 President of the Republic of South Africa v Hugo 1997 (4) SA 1 (CC) at para 41.

3 Westen P "The empty idea of equality" (1982) 95(3) Harvard Law Review 537 at 543.

4 National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice 1998 (12) BCLR 1517 (CC) at para 72.

5 Hugo (1997) at para 41.

6 Harksen v Lane 1997 (11) BCLR 1489 (CC) at para 43.

7 City Council of Pretoria v Walker 1998 (3) BCLR 257 (CC).

8 See Minister of Finance and another v Van Heerden 2004 (6) SA 121 (CC); Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie 2006 (1) SA 524 (CC); Khosa v Minister of Social Development 2006 (6) SA 505 (CC); Ab v Minister of Social Development 2017 (3) SA 570 (CC); MEC for Education KwaZulu-Natal v Pillay 2008 (1) SA 474 (CC); Social Justice Coalition and others v Minister of Police and others 2019 (4) SA 82 (WCC); South African Navy and another v Tebeila Institute of Leadership, Education, Governance and Training [2021] 6 BLLR 555 (SCA); Government of the Republic of South Africa and others v Grootboom and others 2001 (1) SA 46; National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice and others; Jordan and others v State 2001 (6) SA 642 (CC); Naidoo v Minister of Safety and Security and Another 2013 (3) SA 486 (LC); Rates Action Group v City of Cape Town 2004 (12) BCLR 1328 (K); Manong and Associates (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town 2009 (1) SA 644 (EqC); Mvumu v Minister of Transport 2011 (5) BCLR 488 (KH).

9 For example commercial, agricultural, residential and conservation categories.

10 Harksen v Lane (1997) at para 53. See also Prinsloo v Van der Linde 1997 (3) SA 1012 (CC) at para 17.

11 Harksen v Lane (1997) at para 53.

12 Zuma v Democratic Alliance 2018 (1) SA 200 (SCA) 674 (CC).

13 Harksen v Lane (1997) at para 53.

14 Section 9(5) of the Constitution.

15 Prinsloo (1997) at para 31; see also Albertyn C & Goldblatt B "Equality" in Woolman S, Bishop M & Brickhill J (eds) Constitutional law of South Africa Cape Town: Juta 2 ed (RS 4 2013) 35-38; Rautenbach IM "Riglyne om die reg op gelykheid toe te pas" (2012) 9(2) LitNet Akademies 229 at 251.

16 Hugo (1997) at para 41; see also Prinsloo (1997) at para 41.

17 Khosa (2006) at paras 74, 76-77. See also Fourie (2006) at para 60.

18 Maseka N & Chasakara R "Fishing for equality in marine spatial planning" 2018 JOLGA 52 at 69.

19 Harksen v Lane (1997) at para 53.

20 Harksen v Lane (1997) at para 53.

21 See Albertyn C "Equality" in Cheadle MH, Davis DM & Haysom NRL (eds) South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights South Africa: LexisNexis (RS 29 2019). This argument appears in the 2019 version only.

22 Goldswain G "Are some taxpayers treated more equally than others? A theoretical analysis to determine the ambit of the constitutional right to equality in South African tax law" (2011) 15(2) Southern African Business Review 1 at 6-9.

23 Nondabula v Commissioner: SARS and Another 2018 (3) SA 541 (ECM).

24 Nondabula (2018) at para 25.

25 Khosa (2006) at paras 74, 76-77.

26 Section 36 of the Constitution.

27 See Albertyn C "Equality" in Cheadle MH, Davis DM & Haysom NRL (eds) South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights South Africa: LexisNexis (RS 31 2021) at 4-60.

28 See Albertyn (2021) at 4-60.

29 Albertyn (2021) at 4-60. See also Davis DM, Cheadle H & Hayson N Fundamental rights in the Constitution: Commentary and cases Cape Town: Juta (1997) at 201; Mubangizi J & O'Shea A The protection of Human Rights in South Africa: A legal and practical guide 2 ed Cape Town: Juta (2013) at 81.

30 Albertyn (2021) at 4-60.

31 Albertyn (2021) at 4-60.

32 Walker (1998) at para 4.

33 Walker (1998) at paras 5-6; 8-19.

34 Walker (1998) at para 12.

35 Walker (1998) at para 5.

36 Walker (1998) at para 6.

37 Walker (1998) at para 23.

38 Walker (1998) at paras 45-56.

39 Walker (1998) at para 27.

40 Walker (1998) at para 31.

41 Walker (1998) at para 33.

42 Walker (1998) at para 36.

43 Walker (1998) at paras 45-48.

44 Walker (1998) at paras 45-48.

45 Walker (1998) at para 49.

46 Walker (1998) at paras 50-51.

47 Walker (1998) at para 50.

48 Walker (1998) at para 65.

49 Walker (1998) at paras 49-67.

50 Walker (1998) at para 68.

51 Walker (1998) at para 68.

52 Walker (1998) at paras 69-81.

53 Walker (1998) at para 81.

54 See section 36(1) of the Constitution; Premier Mpumalanga v Executive Committee of the Association of the Governing Bodies of State-aided Schools, Eastern Transvaal 1999 (2) SA 91 (CC) in this regard.

55 Walker (1998) at para 82.

56 Walker (1998) at para 87.

57 Taxes levied at national level are income tax, turnover tax, dividends tax, capital gains tax, donations tax, value-added tax, transfer duty, estate duty, security transfer tax, customs and excise.

58 Fiscal decentralisation is the transfer of expenditure responsibilities and revenue assignment to lower levels of government. See in general, Ingram GK & Hong YH Fiscal decentralisation and land policies Cambridge:! Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2008); Bird RM & Vaillancourt F (eds) Fiscal decentralisation in developing countries Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1999).

59 Franzsen RCD "Some questions about the introduction of a land tax in rural areas" (1999) 11(2) South African Mercantile Law Journal 259 at 259.

60 See Youngman JM "Tax on land and buildings" in Thuronyi V Tax law design and drafting Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (1996) at 264-265.

61 Section 229(1)(a) of the Constitution; section 2 of the Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004 (MPRA).

62 Section 229(2)(a) of the Constitution; section 17 of MPRA.

63 Section 2 of MPRA.

64 Section 3(1) of MPRA.

65 Section 8(2) of MPRA. Commonly, land is zoned in different municipalities under different categories such as residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural and special zones. The zone category establishes or limits the owner's right of use of her property in accordance with the zone category. For example, a business may not be operated on land that has been zoned as residential and a factory may not be erected on land that has been zoned as agricultural.

66 This value reduction is commonly reflected in customer statements and respective policy documents as a rebate. As such, for ease of reference, we refer to the value reduction as a rebate.

67 Bird RM & Slack E International handbook on land and property taxation Cheltenham: Edward Elgar (2004) at chs 1-2.

68 Bird RM, Slack E & Tassonyi A tale of two taxes: Property reform in Ontario Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2012) at 2-3.

69 Property taxes comply with the requirements in terms of the general deduction formula set out in section 11(a) of the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962 read with section 23(g) of the Income Tax Act. Furthermore, section 23(d) of the Income Tax Act prohibits only the deduction of taxes levied in terms of the Income Tax Act. There are no provisions in the Income Tax Act that prohibit the deduction of property taxes where the expenditure of such property taxes complies with the general deduction formula laid out in section 11(a) read with section 23(g).

70 Bird & Slack (2004) at 1.

71 Ibid.

72 See in general Albertyn (2019).

73 We have pointed out already that the differentiation between property categories serves a legitimate purpose. As property taxes in respect of commercial property are tax-deductible for income tax purposes, a differentiation in rates for commercial properties in different cities is not prima facie unfair. Accordingly, the differentiation in rates for residential properties in different municipalities should be investigated.

74 The national average sales price of properties in South Africa from the third quarter in 2020 is ZAR 1 million. See Property24 "Property trends" (2022) available at www.property24.com/property-trends (accessed 8 June 2022).

75 In this table, the tax base is residential property of a value of ZAR 1 million.

76 City of Cape Town Property rates (2021/2022) (2021).

77 City of Johannesburg Property rates policy (2021/2022) (2021); City of Johannesburg Tariffs 2021/2022 (2021).

78 eThekwini Municipality Tariff tables2021/2022 (2021).

79 Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality Property rates policy; Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality Budget 2021/2022 (2021).

80 Mangaung Municipality Budget 2021/2022 (2021).

81 Industrial, commercial, and residential properties that are situated outside of the city metropole (in rural areas) and not connected to the municipal water, electricity and sewerage system are 100 per cent exempt from property taxes. See para 6(2)(3) of the Sol Plaatje Municipality Property Rates Policy read with the 2020/2021 budget.

82 Mahikeng Municipality Tariffs2021/2022 (2021).

83 Polokwane Municipality Budget2021/2022 (2021).

84 Mbombela Municipality Budget2021/2022 (2021).

85 Section 4(1)(c)(ii) of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000.

86 Section 229(1)(a) of the Constitution.

87 Bird & Slack (2004) at 5, 10. Bird & Slack note that in many developing countries the link between property tax and service delivery is suspect.

88 See Franzsen R & McCluskey W (eds) Property tax in Africa: Status challenges and prospects Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2017) at 83-84.

89 Katz Commission of Inquiry into Taxation Third interim report (1995) at para 7.1.4.

90 World Bank "GINI index - South Africa (2019)" available at https://bit.ly/2Vr3gqM (accessed 16 April 2020).

91 See the different rate structures of the municipalities considered in this research.

92 Franzsen RCD "Property tax: Alive and well and levied in South Africa" (1996) 8(3) SA Mercantile Law Journal 348 at 348.

93 Murphy J "The constitutional review of taxation" in Jooste R (ed) Revenue law Cape Town: Juta (1995) 89 at 95.

94 Smith A An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations Vol. 2 London: W Strahan & T Cadell (1776) book V part II.

95 Smith (1776) book V part II.

96 Williams DW & Morse G Davies principles of tax law 4 ed London: Sweet & Maxwell (2000) at 6; Bird RM & Zolt EM Introduction to tax policy design and development draft prepared for a course on practical issues of tax policy in developing countries Washington, DC: World Bank at 15-16; Zolt EM "Revenue design and taxation" in Moreno-Dodson B & Wodon Q (eds) Public finance for poverty reduction: Concepts and case studies from Africa and Latin America Washington, DC: World Bank (2007) at 63. See Zolt (2007) at 63 regarding the problems associated with horizontal equity.

97 Bird & Zolt (2003) at 15-16; Zolt (2007) at 63. See Stiglitz JE & Rosengard JK Economics of the public sector 4 ed New York City: WW Norton (2015) at 525 for problems associated with vertical equity.

98 See in general Sheffrin SM "Fairness and market value property taxation" in Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M Challenging the conventional wisdom on the property tax Columbia: Columbia University Press (2010).

99 Sheffrin (2010) at 248.

100 See the table above.

101 See Property24 Property trends (2022).

102 Ibid.

103 Ibid.

104 Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality Property rates policy available at https://bit.ly/3PXbOIt (accessed 31 January 2022).

105 See Bird & Slack (2004) at 9-10; see in general, Bahl R The property tax in developing countries: Where are we in 2002?Land Lines Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (2001).

106 Ali M, Fjeldstad O & Katera L "Property taxation in developing countries" (2017) 16(1) CMI Brief at 3.

107 Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M 'Whither the property tax: New perspectives on a fiscal mainstay" in Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M (eds) Challenging the conventional wisdom on the property tax Columbia: Columbia University Press (2010) at 6.

108 "The average salaries in 10 major cities across South Africa" Businesstech (24 June 2019) available at https://bit.ly/3be05P9 (accessed 8 June 2022).

109 See the rates table above.

110 Stats SA Community survey (2016) available at http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed 10 June 2022).

111 Ibid.

112 See rates table above.

113 Emphasis added.

114 See Franzsen & McCluskey (2017) at 85.

115 Bahl et al. (2010) at 5.

116 See Ahmad E, Brosio G & Poschl C "Local property taxation and benefits in developing countries: Overcoming political resistance?" 2014 Asia Research Centre Working Paper 65 at 1-4.

117 Bird & Slack (2004) at 15. See also Ali et al. (2017) at 3.

118 Bird & Slack (2004) at 26. See also Muthitacharoen A & Zodrow GR "The efficiency cost of local property tax" in Bahl R, Martinez-Vazquez J & Youngman M (eds) Challenging the conventional wisdom on the property tax (2010) at 15.

119 Ali et al. (2017) at 3.

120 Bird & Slack (2004) at 29-31.

121 Bird & Slack (2004) at 29-31.

122 See in general, Sheffrin (2010).

123 Sieg H Urban economics Princeton: Princeton University Press (2020) at 222-223, 229.

124 Ahmad et al. (2014) at 27.

125 Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality Property rates policy at 17.

126 Stats SA Community Survey (2016).

127 Ahmad et al. (2014) at 27.

128 Stats SA "Statistics by place - Sol Plaatjes" (2011) available at https://bit.ly/3BnO3NY (accessed 16 April 2020).

129 Stats SA "Statistics by place - City of Johannesburg" (2011) available at https://bit.ly/3PDViFH (accessed 16 April 2020).

130 See the general comments by Iles K "A fresh look at limitations: Unpacking section 36" (2007) 23 SAJHR 68 at 70.

131 Rautenbach (2012) at 238.

132 S v Zuma and others 1995 (4) SA BCLR 401 (CC) at 414.

133 Cheadle H "Limitation of rights" in Cheadle MH, Davis DM & Haysom NRL South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights South Africa: LexisNexis (RS 32 2022) at para 30.2.1.

134 Cheadle (2022) at para 30.2.1.

135 Section 36 of the Constitution. See, for example, Metcash Trading Ltd v Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service and another 2001 (1) SA) 1109 (CC) at paras 61-62, where the court ruled that the "pay-now-argue-later" rule in taxation has been adopted in many open and democratic societies.

136 De Reuck v Director of Public Prosecutions 2004 (1) SA 406 (CC) at para 46; Hoffman v South African Airways 2000 (11) BCLR 1211 (CC) at 41; Ramakatsa and Others v Magashule and Others 2013(2) BCLR 202 (CC) at 118.