Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.24 Cape Town 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2077-4907/2020/ldd.v24.12

ARTICLES

Nativism in South African municipal indigent policies through a human rights lens

Oliver Fuo

Associate Professor, School of Undergraduate Studies, Faculty of Law, North - West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1442-8599

ABSTRACT

The dawn of constitutional democracy in South Africa triggered a new wave of immigration into the country. Foreign migrants post-1994 now make up about seven per cent of the country's population. The majority of the new intake are Africans pursuing economic opportunities, or refugees seeking asylum. The convergence of South African citizens and foreigners, especially in the country's major cities, generates competition over space and limited social welfare services which at times degenerates into conflicts with dire consequences. Some South African Ministers and local government leaders have resorted to a nativistic discourse to address competition over limited welfare services and to shield themselves for the failures of the State to achieve the large-scale egalitarian transformation envisaged by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. This article uses local government indigent policies to show how several South African municipalities use citizenship as a mandatory condition for accessing free basic services, and discusses how the institutionalised blanket exclusion of foreigners from accessing these services violates the obligation of non-discrimation which is protected in international and South African human rights law. Against the backdrop of the government's socio-economic rights obligations, this article argues that it is necessary for some municipal indigent policies to be amended to at least cater for the basic needs of indigent foreigners with a permanent residence permit and those with official refugee status in South Africa. It is argued that the blanket exclusion of these categories of destitute non-citizens without consideration of their immigration status fails to distinguish between those who have become part of South African society and have made their homes in the country and those who are in South Africa on a transient basis.

Keywords: Nativism, municipal indigent policies, free basic municipal services, socioeconomic rights, foreigners, permanent residents, refugees, South Africa.

1. INTRODUCTION*

The dawn of constitutional democracy in South Africa triggered a new wave of immigration into the country. Klaaren argues that "South Africa is a country made by the history of movement of people" and that this "history-making character of movement across formal borders shows no signs of lessening".1 Foreign migrants post-1994 now make up about 7,1per cent of the country's population.2 The majority of the new intake are Africans pursuing economic opportunities or refugees seeking asylum, and this population is concentrated in Gauteng Province due to its economic vibrancy.3Although the Province extends over only 1,5 per cent of the total land mass of the country, it contributes a third of South Africa's Gross Domestic Product (GDP).4 The City of Johannesburg remains the destination of choice for immigrants to the Gauteng region.5 The convergence of South African citizens and foreigners, especially in the country's major cities, generates competition over space and limited social welfare services. This competition coupled with low levels of economic growth, high levels of unemployment, and socio-economic inequality often lead to conflict and xenophobic attacks.6

South Africa has a law and policy framework that regulates immigration and generally protects the rights of immigrants.7 The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution) provides the overarching legal framework that protects the rights of immigrants in the country.8 The Constitution guarantees everyone a variety of socio-economic and civil and political rights, including the rights to human dignity, non-discrimination and just administrative action.9 In general, although these rights are not absolute,10 it has been argued that commitment to the values of constitutional supremacy and the rule of law theoretically shields foreigners from conduct that is contrary to the Constitution.11 In terms of legislation, the admission of foreigners to, their residence in, and their departure from, South Africa, are mainly regulated by the Immigration Act 13 of 2002.12 The preamble to the Immigration Act 13 of 2002 (Immigration Act) professes the need to establish a system of immigration control that "is performed within the highest applicable standards of human rights protection" and is one that prevents and counters xenophobia within both government and civil society.13 The preambular ideals, reiterated in the objectives of the Immigration Act14 , are in accordance with the constitutional commitment to protect a broad range of human rights.15

In terms of policy, the recently adopted White Paper on International Migration for South Africa (White Paper (2017)) acknowledges that it is neither desirable nor possible to stop or slow down international migration and that "international migration in general is beneficial if it is managed in a way that is efficient, secure and respectful of human rights".16 The 2030 vision for the policy is to embrace international migration for development while safeguarding South Africa's sovereignty, peace and security.17The White Paper (2017) identifies eight priority areas that require policy and strategic interventions in order to realise its vision.18 Based on a review of the legal framework, Ntlama and Landau conclude that South Africa's law offers basic protection to immigrants, irrespective of their legal status, against potential human rights abuses and unconstitutional conduct.19

Despite Ntlama and Landau's conclusion , there has recently been an increase in anti-foreigner sentiment in South Africa.20 Apart from general xenophobic attacks against foreigners in 2010 and 2016, some Ministers and local government leaders have resorted to a nativistic discourse to address competition over limited social services and to shield themselves for the failures of the State to achieve the large-scale egalitarian transformation envisaged by the Constitution.21 They argue that the influx of foreigners, especially from other African countries, limits the ability of the government to provide citizens with the welfare services envisaged by the Constitution.22 In 2017, the former Mayor of the City of Johannesburg, Herman Mashaba, for example, announced the City's housing policy direction to be to the following effect :

" I will do everything possible to provide accommodation. But the City of Johannesburg will only provide accommodation to South Africans. Foreigners, whether legal or illegal, are not the responsibility of the City. I run the Municipality. I don't run national government.... I will do everything possible to provide accommodation, but the City of Johannesburg will only provide accommodation for South Africans."23

Although the Mayor's Office was subsequently forced by a media outcry to change the above policy position, it is just one concrete example of anti-foreigner sentiment expressed in the form of a city's policy direction. In addition, the City of Johannesburg's free basic services policy ("Siyasizana")24 still requires indigent applicants to prove that they are South African citizens in order to access benefits.25

Apart from the above example, the Zulu King, Goodwill Zwelithini, has also been at the centre of several controversial statements accusing foreigners of contributing to poverty and unemployment in South Africa by taking the jobs of citizens.26 The King's last controversial statements were made in 2015 when he asked all foreigners to pack their bags and leave South Africa. He argued that it was unacceptable for citizens to be made to compete with people from other countries for the few economic opportunities available. A few days after the King's remarks, there was an outbreak of violence against foreigners in Durban which subsequently spread to Johannesburg. Seven people were killed and the King was blamed for inciting xenophobic attacks against foreigners through reckless statements.27 Although the King, like other traditional leaders in the country, has limited constitutional and legislative powers,28 he is a local leader that commands the loyalty of about 10 million Zulu people.

At the national level, the former Minister of Health, Aaron Motsoaledi, complained in 2018 that foreigners were burdening the country's health system, and urged South Africa to revisit its immigration policies to control the number of undocumented and illegal migrants in the country. The Minister asserted :

" The weight that foreign nationals are bringing to the country has got nothing to do with xenophobia...it's a reality. Our hospitals are full, we can't control them. When a woman is pregnant and about to deliver a baby you can't turn her away from the hospital and say you are a foreign national...And when they deliver a premature baby, you have got to keep them in hospital. When more and more come, you can't say that the hospital is full now go away.they have to be admitted, we have got no option - and when they get admitted in large numbers, they cause overcrowding, infection control starts failing."29

The statement by the Minister of Health could be seen as an attempt to deflect attention from the government's failure to fix a deteriorating public health system that generally continues to fail to meet the basic standards of care and patients' expectations.30

In a critical scholarly analysis of how nativist discourses have helped in shaping areas of exclusion in post-apartheid South African cities, Landau observes :

" The convergence of newly urbanised South Africans and non-nationals in an environment of resource scarcity, combined with economic and political transition, has placed a premium on the rights to residence, employment and social services. The criteria for exercising these rights - with restrictions enforced by state agents and new immigration legislation - have increasingly made full access to city resources and residences contingent on individuals' South African lineage. Pressure and efforts to exclude non-indigenous populations in the name of South African sovereignty and South Africans' rights and prosperity have led the government to declare a 'state of exception'. Under these conditions, efforts to alienate and 'liquidate' the cities' non-national populations are, with state sanction, taking place outside the normal rule of law."31

The findings of Landau summarised in the above extract are troubling given South Africa's constitutional human rights commitments. In addition, this appears to run against the assertion in the Constitution that "South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity."32

Against the above background, this article uses local government indigent policies to show how several South African municipalities use citizenship as a mandatory condition for accessing free basic services, and discusses how the institutionalised blanket exclusion of foreigners violates the duty of non-discrimation which is protected in the Constitution and international human rights law. Drawing from international human rights law and domestic socio-economic rights jurisprudence, this article argues that it is necessary for some municipal indigent policies to be amended to at least cater for the basic needs of certain categories of poor foreigners living in South Africa. This article begins, in part 2 below, by discussing the duty of non-discrimation in international and African regional socio-economic rights law with the aim of showing the extent to which it guides host countries in limiting the socio-economic rights of non-nationals. Part 3 discusses how the free basic services policies of South African municipalities generally fit into their constitutional socio-economic rights obligations. It also looks into the eligibility requirements for accessing free basic services in the indigent policies of a number of municipalities. Drawing from international law and domestic socio-economic rights jurisprudence, part 4 discusses why the current blanket exclusion of foreigners in some local indigent policies is contrary to the socio-economic rights obligations of municipalities. The article ends with a conclusion.

2. THE INTERNATIONAL LAW POSITION

Apart from its traditional role of regulating relations amongst States, international law also creates obligations that State Parties owe to individuals as human beings, including non-citizens.33 Although there are a myriad of international law instruments that protect the rights of immigrants,34 the focus here is mostly on the main instrument guaranteeing non-discrimination in the implementation of socio-economic rights - the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966 (ICESCR).35 The ICESCR obliges State Parties to ensure that the variety of socio-economic rights enunciated in the Covenant are enjoyed by everyone without any kind of discrimination, such as, national origin or any other status.36 This obligation is expressed and qualified by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)37 in General Comment 20 as follows:

" Differentiated treatment based on prohibited grounds will be viewed as discriminatory unless the justification for differentiation is reasonable and objective. This will include an assessment as to whether the aim and effects of the measures or omissions are legitimate, compatible with the nature of Covenant rights and solely for the purpose of promoting the general welfare in a democratic society. In addition, there must be a clear and reasonable relationship of the proportionality between the aim sought to be realised and the measures or omissions and their effects. A failure to remove differential treatment on the basis of a lack of available resources is not an objective and reasonable justification unless every effort has been made to use all resources that are at the State party's disposition in an effort to address and eliminate the discrimination, as a matter of priority.38 Under international law, a failure to act in good faith to comply with the obligation in article 2, paragraph 2, to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the Covenant will be exercised without discrimination amounts to a violation. Covenant rights can be violated through the direct action or omission by State parties, including through their institutions or agencies at the national and local levels."39

It follows that any limitation on the extent to which non-citizens enjoy access to socio-economic rights must be reasonable and objective and justified on the basis of the proportionality principle. Therefore, there are limited circumstances in which governments can legitimately permit differences in treatment between citizens and non-citizens or between groups of non-citizens, such as between permanent and temporary residence permit holders.40 Despite the margin of discretion enjoyed by governments in assessing whether and to what extent differences in otherwise similar situations justify different treatment, they must justify how such different treatment, based exclusively on nationality or legal status, is in accordance with the principle of non-discrimination.41

Despite the general obligation with respect to non-discrimination, Article 2(3) of the ICESCR provides that "[d]eveloping countries, with due regard to human rights and their national economy, may determine to what extent they would guarantee the economic rights recognised in the present Covenant to non-nationals".42 From the wording of Article 2(3) of the ICESCR and General Comment 20 of the CESCR, it is clear that the obligation with respect to non-discrimation in the realisation of socio-economic rights is not absolute. The standard of justification for excluding non-nationals from socio-economic rights programmes appears lower for developing countries. The exception created by Article 2(3) of the ICESCR for developing countries seems to be a flexible mechanism that seeks to take into account country variations. From the perspective of developing countries, it seems to recognise their socio-economic context where many governments struggle to extricate a significant proportion of their populations from extreme levels of poverty and hardship.43 Just like the ICESCR, the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights (1981) (African Charter) prohibits any discrimination in the enjoyment of guaranteed rights on the basis of national origin, for example.44 Any discrimination against individuals in their access to or enjoyment of socio-economic rights on any of the prohibited grounds is considered a violation of the African Charter.45 Discrimination in this context has been defined as any conduct or omission which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the equal access to and enjoyment of a socio-economic right.46

According to the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR), the obligation to protect the individual from discrimination in the enjoyment of access to socio-economic rights is immediate.47 It is important to note that the ACHPR does not identify the level of economic development in a country as a justifiable basis for discriminating against non-nationals in the provision of socio-economic rights. The ACHPR puts emphasis on the need for Member States to ensure that members of vulnerable and disadvantaged groups are catered for.48 This includes vulnerable non-nationals. This shows that the position adopted by the ACHPR is more generous compared to the exception granted in Article 2(3) of the ICESCR.

It is important to note that the exception to the princiciple of non-discrimation in international socio-economic rights jurisprudence adopted by the CESCR does not apply to refugees. The position of refugees is regulated by the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) (UN Refugees Convention) 49, as amended by the UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (1967).50 The 1967 UN Protocol gave the 1951 UN Refugees Convention universal coverage.51 Article 3 of the UN Refugees Convention guarantees the principle of non-discrimation and obliges Contracting States to apply the provisions of the Convention without discrimation as to race, religion or country of origin. This obligation is reiterated in several Articles in Chapter IV of the UN Refugees Convention dealing with welfare. For example, Article 20 dictates that where a rationing system exists for the distribution of welfare products that are in short supply, refugees should be accorded the same treatment as nationals.

In terms of Article 22 of the UN Refugees Convention, Contracting States are required to accord refugees the same treatment as that accorded to nationals with respect to elementary education. In addition, Article 23 of the UN Refugees Convention obliges Contracting States to accord refugees lawfully staying in their territories the same treatment with respect to public relief and assistance as accorded their nationals. These provisions show that the UN Refugees Convention provides very strong human rights protection to refugees in relation to welfare provision. The obligation with respect to non-discriminaton is equally protected in Article 5 of the African Union Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (1969) (AU Refugees Convention).52 South Africa acceded to the UN Refugees Convention and its 1967 Protocol on 12 January 1996, and ratified the AU Refugees Convention on 15 January 1996.

Apart from non-discrimination, the obligation of non-retrogression in the realisation of socio-economic rights is equally applicable to non-nationals.53 This obligation simply means that governments are prima facie considered to be in violation of their treaty obligations when they implement measures that reduce the enjoyment of socio-economic rights by individuals or peoples.54 The obligation on non-retrogression is not absolute and any retrogressive measures must always be justified in the light of the totality of the rights guaranteed and in the context of the full use of the maximum available resources.55 In assessing whether a State Party has violated the obligation of non-retrogression, it has to be considered whether: there is reasonable justification for the action; alternatives were comprehensively examined and those which were least restrictive of protected human rights were adopted; there was genuine participation of affected people in examining the proposed measures and alternatives; the measures were directly or indirectly discriminatory; the measures would have a sustained impact on the realisation of the protected right; the measures had an unreasonable impact on whether an individual or group was deprived of access to the minimum essential level of the protected right; and there was independent review of the measures at the national level.56 Although these factors are supposed to be taken into consideration in determining a violation of the obligation of non-retrogression, there is no requirement that the same weight should be placed on all relevant factors.

General Comment 20 of the CESCR stresses that Covenant rights can be violated through the direct action or omission by the institutions or agencies of State Parties at the national and local levels.57 This means that national and sub-national levels of government are generally obliged to comply with socio-economic rights obligations emanating from the ICESCR. Due to the ratification of the UN Refugees Convention, the AU Refugees Convention , and the African Charter in 1996 , as well as the ICESCR in 2015, there can be no doubt that South Africa is obliged to comply with its international and African regional socio-economic rights obligations. In South Africa, national government enjoys exclusive competence in negotiating and concluding international agreements.58 The same is true in the area of immigration control, which flows from the constitutional law principle that a matter not allocated under either Schedule 4 or Schedule 5 of the Constitution is a national competency.59 Due to these exclusive powers, national government is expected to take the lead in putting in place (framework) legislation and policies that ensure that the international human rights duty of non-discrimination in the enjoyment of socio-economic rights is protected in South Africa.60 As will become evident in the discussion in parts 3 and 4 below, this national framework already exists in South Africa - and in fact predates the ratification of key instruments, such as the ICESCR.

However, despite the exclusivity of national government's competence in respect of immigration control and the negotiation and ratification of international agreements, ratified international instruments are binding on the entire South African State. This means that all State institutions, including the local sphere of government (constituted by 257 municipalities) must comply with international law obligations. The need to join hands with national government in realising the commitments in the ICESCR, the UN Refugees Convention, the African Charter , and the AU Refugees Convention, is reinforced by the clarion constitutional injunction for all three spheres of government in South Africa (national, provincial and local) to "secure the well-being of the people of the Republic".61 As will become evident from the discussion below, all three spheres of government in South Africa are co-responsible for realising socio-economic rights.

3 OBLIGATION OF MUNICIPALITIES TO PROVIDE FREE BASIC SERVICES

As already indicated in the Introduction above, Chapter 2 of the South Africa Constitution (the Bill of Rights) guarantees a variety of socio-economic rights.62 The socio-economic rights entrenched in the Bill of Rights include the right of "everyone" to access: housing; healthcare services, including reproductive health care; sufficient food and water; and social security, including, if they are unable to support themselves and their dependents, appropriate social assistance.63 In addition, the Constitution also guarantees everyone the right to a healthy environment; the right not to be arbitrarily evicted from one's home; the right not to be refused emergency medical treatment; the right of citizens to access land; the socio-economic rights of children; the right to basic and further education; and the socio-economic rights of detained persons.64 Apart from explicitly guaranteed socio-economic rights, there is an implicit "public law" right of community residents to receive basic services, such as, electricity and sanitation services.65

It is now common knowledge that the socio-economic rights guaranteed by the Constitution impose legally binding duties on the State and that these are shared by the country's three spheres of government (national, provincial and local) and other organs of State, albeit in varying degrees.66 Local government, constituted by about 257 municipalities of varying sizes, is legally required in terms of the Constitution to contribute, together with national and provincial government, to the progressive realisation of constitutional socio-economic rights.67

The nature of the obligations imposed by constitutional socio-economic rights on the government of South Africa has been extensively interpreted especially by the Constitutional Court in a number of landmark cases.68 In terms of the entitlement of foreigners to receive welfare benefits emanating from constitutional socio-economic rights, the Constitutional Court's judgment in Khosa v Minister of Social Development, Mahlaule v Minister of Social Development 2004 (6) BCLR 569 (CC) (Khosa case (2004)) remains the leading authority. In this case the Court declared the exclusion of permanent residence permit holders from accessing social assistance benefits to be unconstitutional and in violation of their right of access to social assistance guaranteed in section 27(1)(c) of the Constitution.69 In the same vein, the Eastern Cape High Court equally delivered a ground-breaking judgment in December 2019 that affects the right to basic education for children that are non-South Africans. The Court ruled that children, irrespective of documentation or immigration status, have the right to free basic education based on the country's international human rights obligations and the principle of the best interests of the child guaranteed in the Constitution.70

Apart from obligations directly emanating from the Constitution, local government also derives socio-economic rights duties from national and provincial legislation and policies. This is so because national and provincial government have powers to regulate how municipalities execute their powers and functions by setting guidelines and minimum standards for the provision of social services.71

It is important to note that the provision of welfare services to those in dire need does not always emanate from obligation imposed by socio-economic rights legislation in South Africa. For example, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the President declared a state of disaster and a nationwide lockdown under the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (DMA) in March 2020. In order to cushion the shock of the lockdown on the poor, the President subsequenty announced several welfare relief measures. In this regard, on 21 April 2020 President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that a special COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant of R350 would be paid monthly to unemployed individuals who do not receive any form of social grant.72 In accordance with the DMA, the Minister of Social Development issued directions for the payment of the SRD grant.73Under those directions only South African citizens, permanent residents and refugees registered with the Department of Home Affairs were eligible for the SRD grant that would be paid for six month, until the end of October 2020. However, following a finding by the Pretoria High Court that the exclusion of asylum seakers and special permit holders was unconstitutional and invalid,74 the Minister made amendments to her directives in order to extend the SRD grant to these categories of foreigners whose permits or visas are valid or were valid on 15 March 2020 when the national lockdown was declared.75 Unfortunately, because the order of the Court could not be found by the author, it is difficult to comment on the reasoning of the Judge. Prior to this judgment, there were reports and complaints about the government's exclusion of vulnerable foreigners in the distribution of COVID-19 food relief packages.76 The order of the Court relating to the SRD grant will surely guide the government's future COVID-19 welfare relief measures.

The subsection that follows briefly discusses the nature of the powers and functions of local government in post-apartheid South Africa and its mandate to provide welfare services.

3.1. Post-apartheid local government

The adoption of the Constitution profoundly transformed the face and mandate of local government in South Africa. The Constitution established local government as a distinct sphere of government with a significant degree of legislative, executive and fiscal autonomy.77 Although interrelated to and interdependent with national and provincial government, local government is a distinct sphere of government with legislative and executive powers that are exercised through democratically elected municipal councils.78 Municipalities enjoy original legislative powers over a wide range of functional areas listed in Schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution.79 National and provincial governments are barred from compromising or impeding the ability or right of municipalities to exercise their constitutional powers or perform their functions.80The exercise of the original powers and functions of municipalities is only subject to constitutionalism, and constitutionally guaranteed powers can only be removed through an amendment of the Constitution.81 This marks a radical departure from the apartheid system of local government where municipalities were strongly controlled by national and provincial governments and their very existence could be terminated at any time by national and provincial legislatures.82

The autonomy of local government is not absolute. Local government is subject to national and provincial supervision (which includes the powers to regulate, monitor, support and intervene in local government affairs)83 and all three spheres of government must work together in a constitutional system of cooperative governance to secure the wellbeing of the people of South Africa.84 This requires that the three spheres cooperate with one another in mutual trust and good faith by - fostering friendly relations, assisting and supporting one another, consulting one another on matters of common interest, coordinating their actions and legislation with one another, and avoiding legal proceedings against one another.85

Futhermore, another important aspect of local government's transformation is its new constitutional mandate. Although service delivery still remains the cardinal function of municipalities, they now have an expanded constitutional mandate.86Municipalities are constitutionally mandated to promote democratic and accountable governance, provide services to communities in a sustainable manner, promote socioeconomic development, protect and promote a healthy environment, and facilitate the participation of local communities in local governance.87 In addition, as already indicated above, municipalities must contribute, together with other organs of State, towards the progressive realisation of constitutional socio-economic rights.88 This broad developmental mandate is captured in the notion of "developmental local government" which is defined in the 1998 White Paper on Local Government as:

" Developmental local government is local government committed to working with citizens and groups within the community to find sustainable ways to meet their social, economic and material needs and improve the quality of their lives . . In future, developmental local government must play a central role in representing our communities, protecting our human rights and meeting our basic needs. It must focus its efforts and resources on improving the quality of life of our communities, especially those members and groups within our communities that are most often marginalised or excluded, such as women, disabled people and very poor people."89

The core business of each municipality in terms of the new developmental mandate is therefore to meet the basic needs of poor and vulnerable members of their communities and to protect their fundamental rights. In order to bring their developmental mandate to fruition, municipalities are constitutionally obliged to structure and manage their administration, budgeting and planning processes in a manner that promotes socio-economic development and gives priority to the basic needs of communities.90 The obligation on municipalities to meet the basic needs of those living in poverty is further reinforced by the duties imposed by the National Framework for Municipal Indigent Policies 2006 (NIP).

3.2 The obligation to provide free basic services

Apart from the specific constitutional obligations imposed on local government to adopt and implement by-laws and other measures, such as, policies, plans and programmes to realise socio-economic rights, national legislation and policies often impose specific duties related to socio-economic rights on municipalities.91 National legislation and policy may specifically determine the quantity or quality of social goods that municipalities should provide to communities , or define minimum standards for the provision of social goods and services.92 The NIP is a good example in this regard.

The NIP was adopted by the national government in 2006 to replace existing fragmented policies dealing with the provision of free basic services to people living in poverty. The aim of the NIP is to ensure that indigents and indigent households in South Africa are provided a social safety net through the guarantee of access to an essential package of free basic services that will facilitate their healthy and productive engagement in society.93 The NIP is one of the measures adopted to give effect to constitutional socio-economic rights and provides a key platform "for upholding the notions of public good inherent in the Constitution".94 The NIP defines an indigent as anyone "lacking the necessities of life", seen as "goods and services . considered as necessities for an individual to survive".95 The NIP identifies sufficient water, basic sanitation, refuse removal in denser settlements, environmental health, basic energy, health care, housing, food and clothing, as relevant goods and services.96

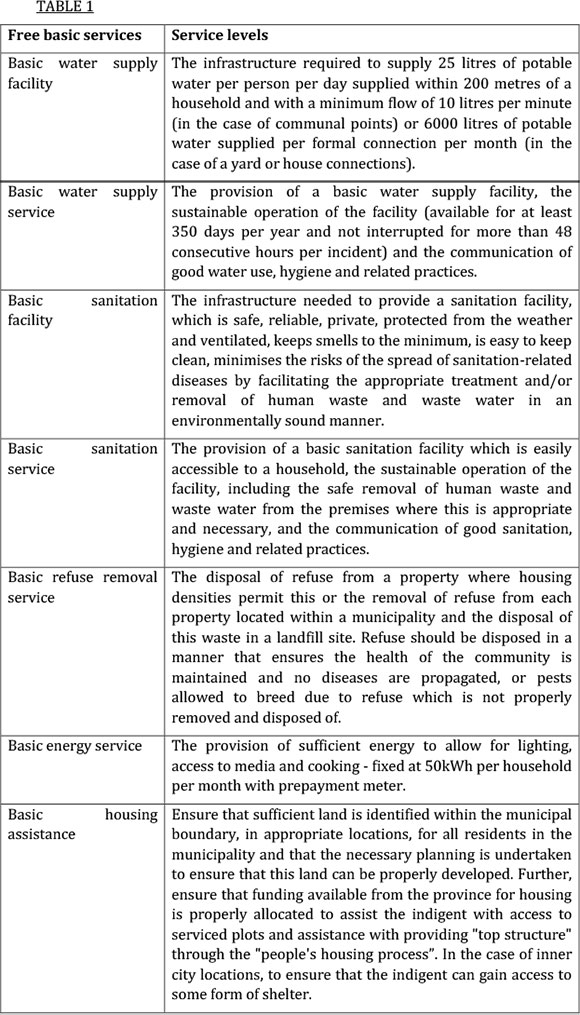

According to the NIP, anyone who does not have access to these goods and services is indigent.97 Due to the fact that some of the goods and services identified in the NIP are not within the areas of competence of local governments, it envisages that the role of municipalities should be focused on providing indigents and indigent households with water, sanitation, basic energy, refuse removal services and assistance in the housing process.98 The levels of free basic services which municipalities are obliged to provide to indigents in terms of the NIP are outlined in Table 1 below (NIP at 21-23):99

The NIP provides a framework which should be used by municipalities to develop and implement their own context specific indigent policies.100 Municipalities that have the necessary resources can provide higher levels and a wider range of free basic services.101 The NIP envisages that the provision of free basic services will be financed largely through three sources: cross-subsidisation where high income consumers of a particular service subsidise the consumption of the poor; revenue generated by municipalities through property rates and other tariffs; and from national equitable share allocations that are made to municipalities on an annual basis.102 There is a strong emphasis on the national equitable share allocation in order to support the financial sustainability of the free basic services programme.103 This takes into account the severe financial pressures faced by most municipalities and their general lack of the fiscal resources needed to deliver on their developmental mandate.104

Although the NIP requires municipalities to specifically target indigents and indigent households through a variety of options,105 it emphasises the need for inclusivity in the provision of free basic services. It stresses that, in line with the values in the Constitution, provision should "specifically exclude discrimination on the grounds of race, gender, disability or sexual orientation".106 It asserts that the duty of non-discrimination has significant implications in the design of municipal indigent programmes. First, "it must be accessible for all residents, implying that currently unregulated settlements (and those living in backyards) must be brought into the municipal system so that residents are not excluded from indigent support". Secondly, municipal indigent support "must not entrench discriminatory land and housing allocations, for example in the areas of traditional tenure where gender discrimination has been an issue".107 It is important to note that the NIP does not mention discrimination on the basis of nationality and this is understandable as this does not appear as a listed ground for non-discrimination in section 9(3) of the Constitution.108

The intention behind the NIP was to ensure that all indigents would have access to free basic services by 2012, including access to land for housing.109 Despite the ambitious timeframe, it is common knowledge that these goals have not been fully achieved in 2020. The levels of free basic services guaranteed in the NIP have been criticised as insufficient in addressing the needs of those living in poverty, and that this might reinforce poverty rather than alleviate it.110 Despite these weaknesses, the NIP is flexible as it encourages municipalities that have the resources to go beyond the range and levels of free basic services guaranteed at the national level.111 Regardless of the flexibility mechanism built into the NIP, a significant number of municipalities are unable to provide even basic services to communities. In early 2020, 40 municipalities across the country were placed under provincial administrations in terms of section 139 of the Constitution because of their inability to deliver on their core constitutional mandate.112 The dire state of affairs in some municipalities is attributed to high levels of corruption and financial mismanagement coupled with the unwillingness of customers to pay for municipal services.

The Auditor-General of South Africa's 2018-2019 Consolidated General Report on the Local Government Audit Outcomes shows that accountability for financial and performance management continues to worsen in most municipalities.113 The Report shows that although billions of rands are transferred to municipalities every year, no proper care is applied to manage and spend the limited fiscal resources diligently as prescribed by law. The lack of proper oversight and very weak accountability continue to expose public money to abuse. This cancerous shadow does have (and has had) an inimical effect on most municipalities' ability to provide the most basic of services to "anyone" living within their jurisdictions.

Notwithstanding the above , the author reviewed the indigent policies of 22 municipalities that appear in Table 2 below for purposes of this article. This evaluation was done by electronically obtaining and thereafter scrutinising the indigent policies of 22 municipalities that reflect the urban, semi-urban and rural matrix of municipalities in the country. However, it should be emphasised that these municipalities do not constitute representative "case studies".114 The reviewed indigent policies show different eligibility criteria as well as levels and range of free basic services as outlined in Table 2 below. It should be noted that in terms of Table 2, where the requirement is a South African Identity Document (SA ID), it means that both citizens and foreigners with a permanent residence permit who have obtained a SA ID are eligible and can apply. Where "N/A" ("no answer") is used, it means the relevant indigent policy is silent on the category of indigent foreigners. Where "Yes" appears in the "No discrimination" column it means that South Africans and all categories of foreigners within the jurisdiction of the municipality can apply for indigent benefits subject to defined income threshold requirements.

Table 2 above shows that while most municipalities are providing the minimum evels of free basic services prescribed in the NIP, some (such as, the City of Tshwane, Zity of Cape Town, eThekwini Metro, and Nelson Mandela Bay Metro) are going beyond îationally prescribed minimum levels and ranges.

What is critical to note for present purposes, is that ten of the 22 municipalities reviewed, prescribe citizenship as an eligibility requirement for accessing free basic services: Bitou Local Municipality;115 Beaufort West Municipality;116 City of Polokwane;117 Dipaleseng Local Municipality;118 Elias Motsoaledi Local Municipality;119Endumeni Local Municipality;120 Great Kei Local Municipality;121 Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality;122 Lesedi Local Municipality;123 Thabazimbi Local Municipality;124 and Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality.125 The indigent policies of eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality126 and Ekurhuleni City127 expressly provide that citizens and foreigners with permanent residence permits can apply for free basic services. In Amahlathi Municipality,128 Cederberg Local Municipality,129 Chris Hani District Municipality,130 the City of Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality,131 Emfuleni Local Municipality,132 and Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality,133 applicants are required to submit a valid SA ID. The requirement for a valid SA ID implies that, in these six municipalities, only citizens and "foreigners" who are permanent residents with a SA ID, can apply for free basic services. Foreigners with permanent residence certificates who have not yet obtained a SA ID may not be able to apply for these services. In Buffalo Metropolitan Municipality, applicants must be citizens or show that they have "recognised refugee status".134 From the indigent policy position in Buffalo Metropolitan Municipality,135 it is not clear whether foreigners permanently residing within its jurisdiction can receive free basic services.

In City of Matlosana,136 Dihlabeng Local Municipality,137 and Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality,138 all indigent households quality for the levels of free basic services prescribed in their indigent policies. In Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, all residential property with a value of R100 000 and less are automatically granted indigent assistance subject to certain verification processes. In Matlosane City, households with a combined household income of less than R7 500 qualify for indigent relief. There is no requirement for citizenship or a SA ID. In Dihlabeng Local Municipality, applicants should "be a resident of South Africa", within the municipality's jurisdiction, and the combined household income must not exceed two old-age grants (maximum of R3 760). The review of the indigent policies of these 22 municipalities reveals inconsistencies in qualifying criteria for accessing free basic services.

It is important to note that until 2017, the practice in the City of Johannesburg was to provide free basic water to all residents within its jurisdiction subject to a block-tariff system which ensured that consumers paid high rates on water once the free quantity had been used. This implies that indigent foreigners in the City received the levels of free basic services prescribed in the NIP. However, in a media statement in 2017, the City announced :

" It is the trend across our country's metros to no longer provide free basic water to all residents, but only to registered indigent residents, which is in line with the National Water Policy and recommended by National Treasury.

In line with our commitment to care for the poorest members of our society, we will continue to provide free basic water to residents on the City's indigent list. Depending on household income, our poorest residents will receive up to a maximum of 15 kilolitres of free water per household, per month in line with the CoJ [City of Johannesburg's] Extended Social Package Policy.

Given the scarcity of water in Johannesburg, the huge inequality in our City, domestic users who do not qualify as indigents will no longer receive the 6kl FBW and therefore see an increase of R42.84 per month to their water bill as a result of this change ...."139

With the recent requirement for citizenship, the above pronouncement means that non-nationals no longer qualify for access to free basic services in the City of Johannesburg. The Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI) has shown that the new approach adopted by the City has resulted in higher margins of exclusion with negative impacts on poor households.140

From the above discussion it appears that, amongst the municipalities reviewed, there are ten South African municipalities that have expressly made citizenship a mandatory requirement for accessing free basic services in their indigent policies; six have provisions which make poor foreigners with a permanent residence permit eligible for free basic services; one expressly makes provision for refugees with official status; and three make provision for all foreigners whose household income is below a defined threshold to appply. The paragraphs that follow show that the mandatory requirement for citizenship in indigent policies and the rollback policy position of the City of Johannesburg may be in violation of important socio-economic rights duties of local government emanating from the Constitution and international human rights law.

4 EVALUATING EXCLUSIONS IN LOCAL INDIGENT POLICIES AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS

4.1. The principle of non-retrogression

First, it is obvious that the decision of the City of Johannesburg in 2017 to curtail universal access to free basic water services was a retrogressive measure because it reduced enjoyment of the right to access sufficient water. Although the obligation on non-retrogression is not abosolute,141 SERI argues that the position adopted by the City of Johannesburg violates this duty because the City has not provided sufficient justification for its retrogression as required under international human rights law. As SERI argues, the "City is yet to provide a convincing financial argument for the withdrawal of the universal provision of FBW [Free Basic Water], given that the City's rising block tariff structure had always allowed it to remain financially viable".142 The argument made by SERI is tenable given that the press statement issued by the City in 2017 suggests that it merely followed an emerging trend in other cities.

4.2. Non-discrimination and the position of refugees in South Africa

The discussion above on international human rights law shows that countries that have ratified the UN Refugees Convention are bound to provide refugees with the same welfare benefits provided to their citizens. In terms of this instrument, the obligation on non-discrimination is absolute in relation to the distribution of welfare benefits. As indicated above, South Africa ratified the UN Refugees Convention in 1996 and it is bound by it. The Refugees Act 130 of 1998 gives effect to South Africa's international refugee obligations. In terms of section 27 of the Act, refugees with formal status in South Africa are entitled to the same socio-economic rights guaranteed in the Constitution to South African citizens, except for those rights that are expressly reserved for citizens. In terms of socio-economic rights, the only right reserved for South African citizens is the right of access to land on an equitable basis.143

This means that refugees and citizens have the same entitlement in terms of the right of access to water, social security and social assistance, health care, food, education, and basic municipal services, for example. It therefore follows that the exclusion of poor refugees from accessing free basic services in municipal indigent policies is illegal and stands to be corrected.

4.3. Non-discrimination and the position of South African "permanent" residents

As pointed out in the context of the discussion on international law above, the anti-discrimination obligation is not absolute.144 However, the argument substantiated in this subsection is that any blanket exclusion of foreigners from accessing free basic services amounts to unfair discrimination and a violation of the obligation of non-discrimation in the realisation of socio-economic rights. As already indicated, this international law obligation is guaranteed in the Constitution and the NIP albeit without reference to "nationality"or "national origin".145 Section 9(3) of the Constitution specifically provides: "The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth". Non-discrimation on the ground of national origin can be read in on the basis of the Constitutional Court's socio-economic rights jurisprudence in the groundbreaking Khosa case (2004),146 which predates the NIP.

In this case , litigation centred on the interpretation of the State's duties to provide social assistance in terms of section 27 of the Constitution147, and the constitutionality of certain provisions of the Social Assistance Act 59 of 1992. The applicants, originally Mozambicans, acquired permanent residence status in South Africa in 1991. They challenged the constitutionality of certain provisions of the Social Assistance Act which reserved old age grants, child support grants, and care dependency grants only for South African citizens.148 All the applicants were impoverished and would have qualified for social assistance under the Act but for the fact that they were not South African citizens. They instituted proceedings in the High Court challenging the constitutionality of the relevant provisions of the Act.149 The matter was ultimately settled in the Constitutional Court.

The majority judgment written by Justice Yvonne Mokgoro held that the denial of access to social grants to permanent residents who, but for their citizenship, would qualify for such assistance does not constitute a reasonable legislative measure as contemplated by section 27(2) of the Constitution. According to the Court, the exclusion of permanent residents from the scheme was likely to reduce them to supplicants, a situation which has a severe impact on their rights to human dignity and equality. The Court held that such exclusion amounted to unfair discrimination which cannot be justified under section 36 of the Constitution.150 The Court further held that the Constitution guarantees the right to social security to "everyone" , that by excluding permanent residents from the scheme for social security, the legislation limits their rights in a manner that affects their dignity and equality in material respects, and that sufficient reasons for such invasive treatment of the rights of permanent residents was not established.151 The Court rejected the argument that the State has an obligation towards its citizens first, and that preserving grants for citizens only provides an incentive for permanent residents to naturalise.152

The Court indicated that that this argument, commonly found in American jurisprudence, based on the social contract assumption that non-citizens are not entitled to the full benefits available to citizens , does not accord with the express legislative intention in the Immigration Act of 2002 which provides : "The holder of a permanent resident permit has all the rights, privileges and duties and obligations of a citizen, save for those . which a law or the Constitution expressly ascribes to citizenship".153 This requires that municipalities treat citizens and foreigners with permanent resident permits in the same manner when they give effect to the rights in the Bill of Rights, except where the Constitution or constitutionally compliant legislation provides otherwise.

The Court acknowledged that the concern raised about the possibility of non-citizens becoming a financial burden on the country is legitimate, and that there are compelling reasons why social assistance benefits should not be made available to all who are in South Africa irrespective of their immigration status.154 However, the Court reasoned that the blanket exclusion of destitute non-citizens without consideration of their immigration status failed to distinguish between those who have become part of South African society and have made their homes in the country and those who are in South Africa on a transient basis. According to the Court, the blanket exclusion also failed to "distinguish between those who are supported by sponsors who arranged their immigration and those who acquired permanent residence status without having sponsors to whom they could turn in case of need".155 The Court asserted that permanent residents reside in the country legally and have resided in the country for a considerable period of time, and like citizens, they have made South Africa their home. The Court reasoned that while permanent residents do not have the rights tied to citizenship, such as, political rights and the right to a South African passport, they are for all other purposes much in the same position as citizens. The Court observed that the homes of permanent residents, and in most cases of their families too, are in South Africa.156

In addition to the above reasoning, the Court dismissed, for lack of sufficient evidence, the argument that to include permanent residents in the social assistance scheme would impose an impermissible high financial burden on the State. The Court reasoned that, in any event, the cost of including permanent residents in the social assistance scheme will only be a small proportion of the total cost incurred by the State on a yearly basis.157 The Court found the relevant provisions of the Social Assistance Act unconstitutional and invalid158 , and in order to remedy the defects in the impugned provisions ordered the reading in of the words "or permanent resident" after "South African citizen" in the legislative provisions.159 The effect of this remedial order was to preserve the right to social security to South Africans while making it instantly available to permanent residents.

In effect, the jurisprudence from this judgment meant that citizens and permanent residents have the same socio-economic entitlements flowing from constitutional socio-economic rights. In brief, the decision of the Court was informed by the following factors: that the Bill of Rights enshrines the rights of "all people in our country", and in the absence of any indication that the section 27(1) right is to be restricted to citizens as in other provisions in the Bill of Rights, the word "everyone" in this section cannot be construed as referring only to "citizens";160 foreigners were a vulnerable minority without political clout and therefore deserving of protection; permanent residents already largely enjoy the same rights, duties and priviledges as citizens in terms of the Immigration Act of 2002; and citizenship was a personal attribute that was difficult to change.161

Although the minority judgment written by Justice Ngcobo (with Justice Madala concurring) approached the matter with a different methodology (an analytical framework based on the reasonableness and justification of the exclusion both in terms of sections 27 and 36 of the Constitution, they agreed with the majority judgment with respect to its findings on child grants and care dependency grants as well as the related orders made. However, in relation to old age grants, the minority judgment concluded that the citizenship requirement constituted a reasonable and justifiable limitation in terms of the Constitution.162

According to Justice Ngcobo, the limitation imposed on permanent residents by the impugned legislative provisions was neither absolute nor permanent because permanent residents become eligible for citizenship after a fixed period of time. A permanent resident was only required to reside in South Africa for a continuous period of five years to qualify for citizenship by naturalisation, and the government's policy was to encourage naturalisation.163 Justice Ngobo conceded that although the five year waiting period could prove harmful to permanent residents who are unable to provide for themselves, the same was equally true for South African citizens who had to wait for five years in order to attain the qualifying age for old age grants.164

Justice Ngcobo found that the State had made two convincing submissions for its policy choice. First, it is consistent with the principle that the State is obliged to cater for the needs of its citizens. The State had invested significant financial resources to combat extreme poverty amongst its citizens and its resources were insufficient to confront this challenge. As Justice Ngcobo put it : "The harsh reality is that there are simply insufficient resources available to cater for all the various persons who might enter its borders seeking assistance".165 Secondly, the minority judgment accepted the argument advanced by the government that its policy rationale was aimed at encouraging immigrants to be self-sufficient. Justice Ngcobo accepted the argument that immigrants within the borders of the country should not depend on public resources to meet their needs but rather on their own capabilities and the resources of their families and their sponsors. According to Justice Ngcobo, this policy position must be seen against the need to ensure that the availability of welfare benefits does not constitue an incentive for immigration to South Africa.166 According to Justice Ngcobo, the impugned provisions were reasonably related to a legitimate goal, and that there was a close relationship between the limitation and its purpose.167

Given the decision of the majority of the Constitutional Court in the Khosa case (2004), it seems that the mandatory requirement of citizenship in accessing free basic services in municipal indigent policies violates the obligation of non-discrimation. This requirement is unconstitutional to the extent that it excludes holders of a permanent residence permit from accessing free basic services, for example. A close reading of the judgment reveals that any institutionalised exclusion in South Africa of poor foreigners with permanent resident permits from accessing free basic services in terms of municipal indigent policies is unconstitutional and can neither be justified in terms of the internal limitation clauses inherent in implicated socio-economic rights or under section 36 of the Constitution. The majority judgment expressed the view that even if the government's exclusion of permament residents from social grants was measured in terms of section 36 and not section 27(2) of the Constitution, the policy and legislative provisions would have failed to pass constitutional scrutiny.168

Although the case was decided solely on the basis of the Constitution in 2004, the position adopted in the majority judgment is similar to that recently adopted by the ACHPR in its 2011 Principles and Guidelines on the implementation of socio-economic rights in the African Charter. The ACHPR requires State Parties to implement measures that will cater for the basic needs of vulnerable groups and peoples irrespective of their national origin.169 This standard seems higher than that set out in Article 2(3) of the ICESCR. Under Article 2(3) of the ICESCR, it appears as if it is easy for developing countries with serious socio-economic challenges, like South Africa, to completely exclude non-nationals from accessing free welfare services. The Court therefore appears to have adopted a very humane approach.

4.4. Non-discrimination and the position of non-nationals with a tenous link to South Africa

A major criticism of the current articulation of the non-discrimination obligation in international human rights law is that although it acknowledges that a distinction between citizens and non-citizens is tolerable especially in the developing country context, it does not provide a clear matrix which can be used in allocating benefits.170This difficulty comes across sharply in the Khosa case (2004) judgment. In that case, the Court started by indicating that it is generally necessary to differentiate between people and groups of people in society by classification in order for the State to be able to allocate rights, duties, privileges, and benefits, and to provide efficient and effective delivery of social services. However, the Court indicated that any classification must be reasonable in terms of section 27(2) of the Constitution. The Court observed :

" ... [T]he state has chosen to differentiate between citizens and non-citizens. That differentiation, if it is to pass constitutional muster, must not be arbitrary or irrational nor must it manifest a naked preference. There must be a rational connection between that differentiating law and the legitimate government purpose it is designed to achieve. A differentiating law or action which does not meet these standards will be in violation of sections 9(1) and 27(2) of the Constitution."171

The Court reasoned that while it may be reasonable to exclude non-citizens who have only a tenuous link with South Africa (such as, visitors and illegal immigrants), it is unreasonable to exclude permanent residents.172

The standard articulated by Justice Mokgoro above can be difficult to measure. This complexity is illustrated in the valid concerns raised by Justice Ngcobo about the distinction between permanent residents and other categories of foreigners living in South Africa:

" It is true that permanent residents enjoy a right to work in South Africa, the right to own houses, the obligation to pay taxes, and the responsibility to contribute to the economic growth of South Africa. But some of these privileges and duties also apply to another group of non-citizens - work permit holders. Just as permanent residents, work permit holders may establish a home in South Africa for their families; indeed, members of this group may well elect to become permanent residents. Both groups of non-citizens are under the Constitution entitled to socioeconomic rights. The crucial question is whether social security benefits should be made available to every person who is within our borders. In my view, the state has successfully advanced compelling reasons for limiting the benefits to citizens. The need to reduce the rising costs of operating social security systems, the need to prevent the availability of social security benefits from constituting an incentive for immigration and the need to encourage the immigrants to be self-sufficient."173

The above goes to the heart of the problems associated with the classification or differentiation of non-citizens. The reasoning of the majority of the Court that government could legitimately exclude other categories of foreigners who are in South Africa on a transient basis seems to be at odds with its own principle that programmes adopted to give effect to socio-economic rights cannot meet the reasonableness threshold if it ignores the needs of those in a desperate situation.174 This principle of the Court could suggest that even foreigners with a tenous link to South Africa who are exposed to desperate situations should receive assistance from the State, and that the nature of their benefits can be limited by available resources.175 This thinking is in accordance with the position adopted by the ACHPR which emphasises the need for State Parties to implement measures that specifically cater for the needs of members of vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.176 According to the Court's own interpretation, most of the socio-economic rights in the Constitution are guaranteed to "everyone" and not just citizens. The Court failed to advance reasons for the categorical exclusion of other categories of foreign nationals.177 Therefore, it is up to policymakers in the three spheres of government to decide on which category of foreigners temporary living in South Africa can access welfare services. This position respects the separation of powers doctrine.

5. CONCLUSION

The demise of apartheid in South Africa and the introduction of constitutional democracy ushered in a new wave of African immigrants into the country seeking asylum or lured by the prospects of a better life. Their presence, especially in the country's urban centres, creates competition with citizens over space and access to limited social services which often degenerates into open hostility and conflict wth dire consequences. Recently, some local government leaders have resorted to nativistic politics, blaming foreigners for many of the socio-economic woes currently faced by South Africans living in poverty.

Despite recent anti-foreigner sentiments, South Africa has a law and policy framework that provides basic human rights protection to non-nationals irrespective of their legal status in the country. A central feature of this framework is the guarantee of the right to non-discrimination in the enjoyment of a variety of socio-economic rights guaranteed in the Constitution. Although the duty of non-discrimination in realising socio-economic rights is equally guaranteed in the ICESCR, the UN Refugee Convention, and the African Charter, this article argues that the South African Constitutional Court in the Khosa case (2004) appears to have adopted a very humane constitutional value laden approach to interpreting the State's duty . The Court decided that although nationality does not appear as a listed ground for non-discrimination in the Constitution, indigent foreigners permanently resident in South Africa should be allowed access to social grants for the diverse reasons discussed in part 4.3 above. The Court held that excluding permanent residents could not be justified either in terms of the internal or external limitation clauses in the Constitution. In terms of the Court's jurisprudence, while policy-makers have the discretion to decide on which categories of foreigners temporarily living it South Africa can benefit from the State's welfare programmes, foreigners permanently living in South Africa have the same socioeconomic entitlements as citizens. It was further established that, with regard to refugees, national legislation exists that gives full effect to South Africa's international human rights commitments. As required by the UN Refugees Convention, the Refugees Act of 1998, read in conjunction with the Constitution, guarantees refugees the same socio-economic rights entitlements as South African citizens, except in relation to the right of access to land.

Despite exisiting constitutional and national legislative guarantees and the emanating jurisprudence, especially of the Constitutional Court in the Khosa judgment, the discussion in part 3.2 above shows that several municipalities still use citizenship as a precondition for accessing welfare services. In the City of Johannesburg, for example, such policy position seems to be informed by anti-foreigner sentiments publicly expressed in the media. On the strength of the Court's precedent in the Khosa case and South Africa's international human rights obligations, it is clear that a mandatory blanket exclusion of foreigners from accessing local indigent benefits violates the duty of non-discrimination on the part of municipalities to the extent that foreigners with permanent residence permits and refugees in their jurisdictions are excluded from accessing free basic services. Based on the above findings, it is argued that the relevant provisions of the indigent policies of the ten municipalities identified in part 3.2 above that prescribe citizenship as a mandatory condition for accessing free basic services are unconstitutional and invalid. They stand to be amended to ensure constitutional compliance and to allow indigent permanent resident permit holders and refugees to qualify for free basic services. It is further submitted that it is necessary for the indigent policies of the other municipalities listed in Table 2 above to be amended to expressly provide that permanent residents and refugees are eligible to receive free basic services. These amendments are important to ensure compliance with their socioeconomic rights obligations.

BIBIOGRAPHY

Books

Adam F Free basic electricity: a better life for all Johannesburg: Earthlife Africa (2010). [ Links ]

African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) Principles and guidelines on the implementation of economic, social and cultural rights in the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights Banjul: African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (2011). [ Links ]

Khan F (ed) Immigration law in South Africa Cape Town: Juta (2018). [ Links ]

Liebenberg S Socio-economic rights: adjudicating under a transformative constitution Claremont: Juta (2010). [ Links ]

Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI) Turning off the tap: discontinuing access to free basic water in the City of Johannesburg Johannesburg: Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (2018). [ Links ]

Steytler NC & De Visser J Local government law of South Africa Durban: LexisNexis (2007, 2014 update). [ Links ]

United Nations International migration report: 2017 New York: United Nations (2017). [ Links ]

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Meeting the challenges of unemployment and poverty in Africa Addis Ababa: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2005). [ Links ]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2010). [ Links ]

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) The economic, social and cultural rights of migrants in an irregular situation New York: United Nations (2014). [ Links ]

Chapters in books

Bronstein V "Legislative competence" in Woolman S & Bishop M (eds) Constitutional law of South Africa 2nd ed Cape Town: Juta (2002, 2014 update) 15-1. [ Links ]

De Visser J "Concurrent powers in South Africa" in Steytler N (ed) Concurrent powers in federal systems: meaning, making, managing Leiden: Brill (2017) 223. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004337572013 [ Links ]

Dugard J "Power to the people? A rights-based analysis of South Africa's electricity services" in McDonald DA (ed) Electric capitalism: recolonising Africa on the power grid London: Routledge (2016) 264. [ Links ]

Fuo O "Funding and good financial governance as imperatives for cities' pursuit of SDG 11" in Helmut A & Du Plessis A (eds) The globalisation of urban governance: legal perspectives on Sustainable Development Goal 11 London: Routledge (2019) 87. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351049269-5 [ Links ]

Khan F "Identifying migrants and the rights to which they are entitled" in Khan F (ed) Immigration law in South Africa Cape Town: Juta (2018) 17. [ Links ]

Klaaren J "Historical overview of migration regulation in South Africa" in Khan F (ed) Immigration law in South Africa Cape Town: Juta (2018) 23. [ Links ]

Mosdell T "Free basic services: the evolution and impact of free basic water policy in South Africa" in Pillay U, Tomlinson R & Du Toit J (eds) Democracy and delivery: urban policy in South Africa Cape Town: HSRC Press (2006) 283. [ Links ]

Moyo K "The jurisprudence of the South African Constitutional Court on socio-economic rights" in Foundation for Human Rights Socio-economic rights: progressive realisation? Johannesburg: Foundation for Human Rights (2016) 37. [ Links ]

Ntlama N "The South African Constitution and immigration law" in Khan F (ed) Immigration law n South Africa Cape Town: Juta (2018) 35. [ Links ]

Steytler N "Concurrency of powers: the zebra in the room" in Steytler N (ed) Concurrent powers in federal systems: meaning, making, managing Leiden: Brill (2017) 300. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004337572017 [ Links ]

Venter F "The challenges of cultural diversity for safe and sustainable cities" in Helmut A & Du Plessis A (eds) The globalisation of urban governance: legal perspectives on Sustainable Development Goal 11 London: Routledge (2019) 151. [ Links ]

Journal articles

Botha H "The rights of foreigners: dignity, citizenship and the right to have rights" (2013) 130(4) South African Law Journal 837. [ Links ]

De Visser J "Developmental local government in South Africa: institutional fault lines" (2009) 13 Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 7. https://doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i2.1005 [ Links ]

Fareed Z "Populism on the march: why the West is in trouble" (2016) 95 Foreign Affairs Review 9. [ Links ]

Fuo O "Constitutional basis for the enforcement of 'executive' policies that give effect to socio-economic rights in South Africa" (2013) 16 Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal 1. https://doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2013/v16i4a2381. [ Links ]

Fuo O "Local government indigent policies in the pursuit of social justice in South Africa through the lenses of Fraser" (2014) 25 Stellenbosch Law Review 187. [ Links ]

Fuo O "Role of courts in interpreting local government's environmental powers in South Africa" (2015) 18 Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/cjlg.v0i18.4840. [ Links ]

Fuo O "Intrusion into the autonomy of South African local government: advancing the minority judgment in the Merafong City case" (2017) 50 De Jure 324. https://doi.org/10.17159/2225-7160/2017/v50n2a7 [ Links ]

Gerring J "What is a case study and what is it good for?" (2004) 98(2) American Political Science Review 341. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404001182. [ Links ]

Hernandez-Truyol BE & Johns KA "Global rights, legal wrongs and local fixes: an internationa human rights critique of immigration and welfare reform" (1998) 71 Southern California Law Review 547. [ Links ]

Jansen van Rensburg L "The Khosa case - opening the door for the inclusion of all children in the child support grant?" (2005) 20 SA Public Law 102. [ Links ]

Klaaren J "Constitutional citizenship in South Africa" (2010) 8(1) International Journal of Constitutional Law 94. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mop033 [ Links ]

Landau L "Urbanisation, nativism and the rule of law in South Africa's 'forbidden' cities" (2005) 26 Third World Quarterly 1115. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590500235710. [ Links ]

Langa P "Transformative constitutionalism" (2006) 17 Stellenbosch Law Review 351. [ Links ]

Maphumulo W & Bhengu B "Challenges of quality improvement in the healthcare of South Africa post-apartheid: a critical review" (2019) 42(1) Curationis 1. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v42i1.1901. [ Links ]

McConnell C "Migration and xenophobia in South Africa" (2009) 1 Conflict Trends 34. [ Links ]

Motomura H "Federalism, international human rights, and immigration exceptionalism" (1999) 70 University of Colorado Law Review 1361. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni J "Africa for Africans or Africa for 'Natives' only? 'New nationalism' and nativism in Zimbabwe and South Africa" (2009) 44(1) Africa Spectrum 67. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203970904400105. [ Links ]

Pieterse M "What do we mean when we talk about transformative constitutionalism?" (2005) 20 SA Public Law 155. [ Links ]

Van Wynsberghe R & Khan S "Redefining case study" (2007) 6(2) International Journal of Qualitative Methods 80. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690700600208. [ Links ]

Legislation

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Immigration Act 13 of 2002.

Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998.

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000.

Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 41 of 2003.

Government documents

GN R517 in GG 43300 of 9 May 2020.

GN 727 in GG 43494 of 2 July 2020.

National Indigent Policy (2006).

White Paper on Local Government (1998).

White Paper on International Migration for South Africa (2017).

Treaties, conventions and other international documents

African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (1981).

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966).

OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (1969).

United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) "General Comment 20: Non-discrimination in economic, social and cultural rights (art 2, para 2, of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights)" (2 July 2009) UN Doc E/C.12/GC/20.

United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951). United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (1967).

Case law

Centre for Child Law & others v Minister of Basic Education & others [2020] 1 All SA 711 (ECG).

City of Cape Town v Robertson 2005 (2) SA 323 (CC).

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality v Blue Moonlight Properties 39 (Pty) Ltd 2012 (2) BCLR 150 (CC).

Fedsure Life Assurance v Greater Johannesburg Transitional Metropolitan Council 1999 (1) SA 374 (CC).

Government of the Republic of South Africa v Grootboom 2001 (1) SA 46 (CC). Joseph v City of Johannesburg 2010 (3) BCLR 212 (CC).

Khosa v Minister of Social Development, Mahlaule v Minister of Social Development 2004 (6) BCLR 569 (CC).

Lawyers for Human Rights v Minister of Home Affairs 2004 (4) SA 125 (CC).

Maccsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town 2012 (4) SA 181 (CC).

Mazibuko v City of Johannesburg 2010 (4) SA 1 (CC).