Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.24 Cape Town 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2077-4907/2020/ldd.v24.3

ARTICLES

An empirical analysis of class actions in South Africa

Theo Broodryk

Associate Professor, Department of Private Law, Faculty of Law, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2514-4951

ABSTRACT

As far as the author is aware, there has not been an empirical analysis of class actions in South Africa since the introduction of the mechanism by the interim Constitution of 1993 more than 25 years ago. There is no publicly available data which provides meaningful empirical insight into the operation of the South African class action. There is consequently much that we do not know about it. This article attempts to examine class actions over a period spanning more than 19 years. The purpose of the article will be to provide, through an analysis of case law, an empirical exposition of class actions instituted in South Africa using the criteria and methodology mentioned below. The study demonstrates that, although there have been only a limited number of certification judgments delivered to date, there has been rapid growth in the number of certification judgments delivered in the past five years. Most of these judgments are aimed at providing access to justice for poor and marginalised individuals. The data presented herein could place South Africa in the fortuitous position of being able to build a comprehensive data archive in which the class action is statistically dissected. Without comprehensive data concerning the operation of the class action, the available information will be insufficient from the perspective of providing adequate insight to enable its optimal development going forward.

Keywords: Class action; empirical data; access to justice; certification; opt-in; opt-out; bifurcation; settlement

1 INTRODUCTION

The lack of empirical data regarding the South African civil justice landscape is disconcerting. Unfortunately, not much has changed since Erasmus, in 1999, commented as follows:

"We do not, for example, know how many civil cases of a particular nature are instituted in a particular court in a given year; we do not know how many of such cases are determined at a trial and what the median time is for determination at a trial; we do not know what percentage of cases are settled and at what stage of the proceedings they are settled. We have no figures which would enable us to draw the distinction between so-called 'lawyers induced delay' and 'court induced delay'. We do not even know what the real cost of litigation in this country is - the only true indication of the real cost of litigation is the amount paid by the client to his own attorney and this has not been the subject of any comprehensive study. We do not know how we compare with other jurisdictions ... Where do we stand? The little information we do have is insufficient ." 1

The concern regarding the lack of data similarly applies to the operation of the South African class action within the civil justice system. There has, as far as the author is aware, never been an empirical analysis of class actions in South Africa since the introduction of the mechanism in the interim Constitution more than 25 years ago.2There is no publicly available data which provides meaningful empirical insight into the operation of class actions. There is consequently much that we do not know about the mechanism. For example, we do not know how many class actions are filed annually, what the certification rate is, what the settlement rate is, how much money changes hands in class action litigation every year, and so forth. The problem with the paucity of data is that it makes it very difficult to measure progress, to engage with problems , to make suggestions for reforms insofar as the continued development of the class action is concerned, and to measure the impact of such reforms. An intelligent and informed assessment regarding whether our class action mechanism functions optimally is simply not possible.

This article attempts to examine class actions over a period spanning more than 19 years. The purpose of the article will be to provide, through an analysis of case law, an empirical exposition of class actions instituted in South Africa using the criteria and methodology mentioned below. There are many aspects relating to the South African class action which this study does not cover.3 It does not purport to provide an exhaustive overview of class actions. Rather, it has as its purpose, within the framework set out herein, to provide an empirical and factual basis for the conduct of further research and analysis to benefit the continued development of the South African class action.

2 CRITERIA, PURPOSE AND METHODOLOGY

The legal research conducted for the purpose of this study sought to identify case law that meets the following criteria: cases where a South African superior court, sitting as a court of first instance, made a definitive pronouncement4 on whether a matter could proceed5 as a class action6 and where it is clear from the judgment that the applicant(s) intended to frame the matter as a class action. The research is limited to judgments handed down after judgment in Ngxuza and others v Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape and others 7(Ngxuza) was delivered.8Ngxuza was selected as the point of departure because this case formally introduced the notion of class action certification into South African law.9 De Vos comments as follows regarding the judgment of Froneman J in Ngxuza which was subsequently endorsed by the Supreme Court of Appeal:10

"Ngxuza paved the way for the development of our law to accommodate such proceedings. The judgment of Froneman J broke new ground by allowing a class action...even though there was no statute or court rule showing the way forward...An important aspect of the judgment is that Froneman J laid down the requirement that leave must be obtained from the court in order to proceed with a class action, which of course accords with the certification requirement embraced by most class action regimes."11

Appeals in respect of identified case law are reported upon in this article. However, appeals that were first heard before Ngxuza, but where the judgment on appeal was delivered after Ngxuza, are excluded .12The analysis will be conducted with a view to identify and record the following:

1. Cases where a South African superior court, sitting as a court of first instance, made a definitive pronouncement13 on whether a matter could proceed14 as a class action15 and where it is clear from the judgment or order that the applicant(s) intended to frame the matter as a class action.

2. With reference to the cases recorded in relation to 1 above:

a) The nature of the issues to which the cases relate.

b) The dates on which the matters were heard and/or judgments/orders were delivered.

c) The outcomes of the courts' pronouncements in respect of whether the cases could proceed as class actions.

d) The cases where, following the courts' pronouncements that they could proceed as class actions, they did so on an opt-in basis.

e) The cases where, following the courts' pronouncements that they could proceed as class actions, they did so on an opt-out basis.

f) The cases where, following the courts' pronouncements that they could proceed as class actions, they did so on a bifurcated16 basis.

g) The cases in which a superior court approved a class action settlement.

h) Reasons advanced in those cases where courts pronounced that they could not proceed as class actions.

i) The cases in respect of which judgments on appeal have been given in relation to the courts' pronouncements regarding whether a matter could proceed as a class action.

j) The cases that culminated in completed class action trials and, in respect of these cases, whether the applicants were successful.17

The above data will be analysed with a view to possibly drawing conclusions regarding the following issues:

1. The average number of class action certification judgments or orders given annually in South Africa.

2. Whether there has been an increase in the incidence of class actions.

3. If there has been an increase in the incidence of class actions, whether the increase has been gradual or sudden.

4. Whether the class action mechanism is more prone to being used in relation to certain types of issues.

5. What the prospects are that a South African superior court, sitting as a court of first instance, will find that a matter may proceed as a class action.

6. Where a court finds that a matter may proceed as a class action, whether the opt-in, opt-out or bifurcated class action regime is preferred.

7. What the prospects are of a court-approved settlement after a court finds that a matter may proceed as a class action.

8. Whether there are commonly advanced reasons for the decision of a court that a matter may not proceed as a class action.

9. What the prospects are of successfully appealing a decision of a court that a matter may not proceed as a class action.

10. What the prospects are of a class action being litigated to completion.

To conduct the research, the following electronic databases were used: LexisNexis (Lexis), Juta Law (Juta) and Saflii.18 The search methods, in respect of each database, are set out in more detail below.

In relation to Lexis, the "advanced cases search" option was utilised. The words "class action" were inserted in the "[c]ontaining this exact phrase" search option. The search covered the following law reports:

• All South African Law Reports

• Competition Law Reports

• Constitutional Law Reports

• Judgments Online

• Labour Law Reports

• Pension Law Reports

• South African Tax Cases Reports

The search produced 205 results.

In relation to Saflii, the "advanced search" option, using "autosearch", was used. The words "class action" were inserted in the "[t]his phrase" search option. All Saflii databases were included in the search, including the following:

• African Disability Rights Yearbook

• African Human Rights Law Journal

• African Law Review

• Competition Appeal Court

• Constitutional Court

• De Jure Law Journal

• De Rebus

• Electoral Court

• Equality Court

• Free State High Court, Bloemfontein

• High Courts - Eastern Cape

• High Courts - Gauteng

• High Courts - KwaZulu Natal

• Industrial Court

• Labour Appeal Court

• Labour Courts

• Land Claims Court

• Law, Democracy and Development Law Journal

• Law Reform Commission

• Limpopo High Courts

• Mpumalanga High Courts

• Northern Cape High Court, Kimberley

• North Gauteng High Court, Pretoria

• North West High Court, Mafikeng

• Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal

• South Gauteng High Court, Johannesburg

• Supreme Court of Appeal

• Tax Court

• Western Cape High Court

The search produced 157 results.

In relation to Juta, the "advanced law reports search" option was used. The words "class action" were inserted in both the headnote and flynote options. The search results covered Juta's entire Law Reports Series, namely:

• South African Law Reports

• South African Criminal Law Reports

• South African Appellate Division Reports

• South African Case Law

• Burrell's Intellectual Property Law Library

• Industrial Law Journal

• Juta's Unreported Judgments

The search produced 27 results. Thereafter, the same search was conducted having completed only the "headnote" option with the words "class action". The latter search produced 167 results.

The case index of the 2017 publication titled Class Action Litigation in South Africa19lists 148 South African cases.

In respect of the search results of the electronic law databases and the abovementioned publication's case index, 704 in total, each result was individually considered using the abovementioned criteria.

Ultimately, the search produced 15 results in the form of case law which meet the criteria and which form part of this study.20

3 DATA GATHERED

3.1 List of cases

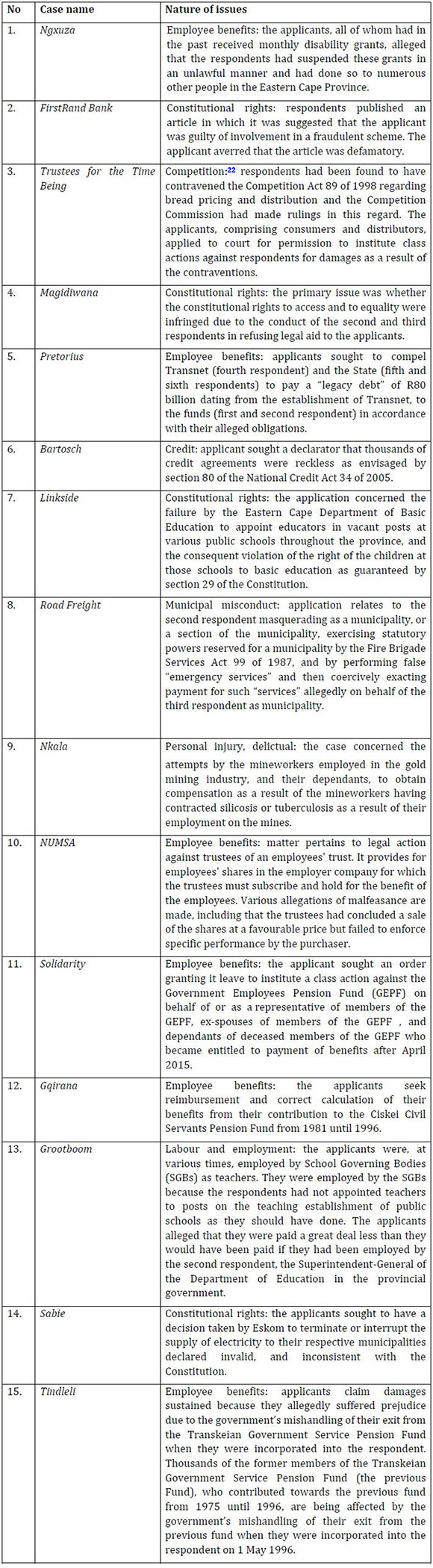

In total, 15 cases were identified where a South African superior court, sitting as a court of first instance, made a definitive pronouncement on whether the matter could proceed as a class action , and where it is clear from the judgment or order that the applicant(s) intended to frame the matter as a class action. These cases are listed in the Table below:

3.2 The nature of the disputes

The nature of the issues to which the cases relate, are listed in the Table below:

3.3 The dates on which matters heard and/or judgments delivered

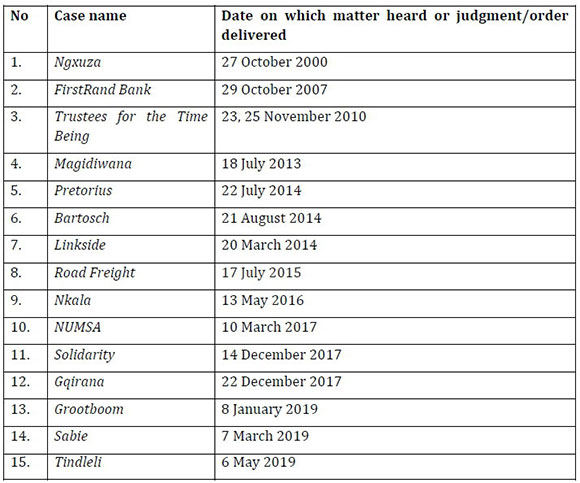

The dates on which the matters were heard and/or judgments/orders were delivered are listed in the Table below:

3.4 Outcomes of pronouncements

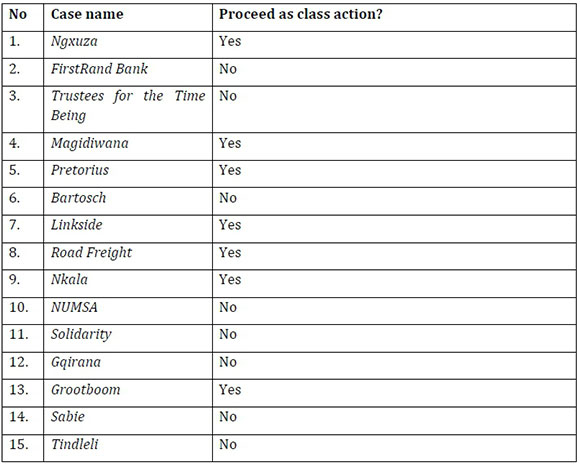

The outcomes of the courts' pronouncements in respect of whether the cases could proceed as class actions are contained in the Table below:

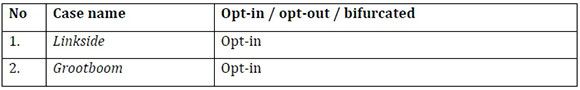

3.5 Opt-in cases

The Table below indicates those cases which, following the courts' pronouncements that they could proceed as class actions, proceeded on an opt-in basis:

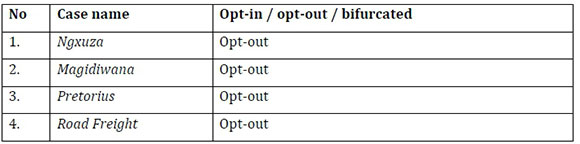

3.6 Opt-out cases

The Table below indicates those cases which, following the courts' pronouncements that they could proceed as class actions, proceeded on an opt-out basis:

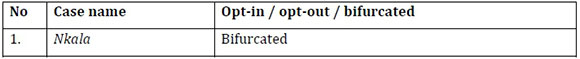

3.7 Bifurcated class actions

The Table below indicates the case which, following the court's pronouncement that it could proceed as a class action, proceeded on a bifurcated basis:

3.8 Court-approved class action settlements

The case in which a superior court approved a class action settlement is set out in the Table below:

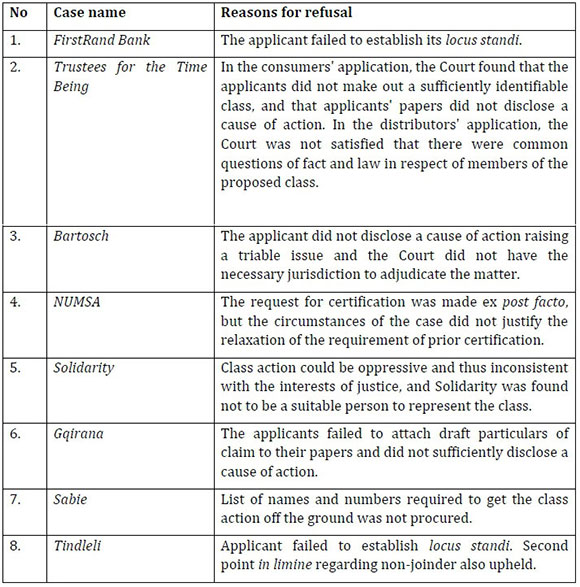

3.9 The reason(s) for refusal

The following Table indicates the primary reasons advanced by courts in those cases in which they pronounced that cases could not proceed as class actions:

3.10 Appeals

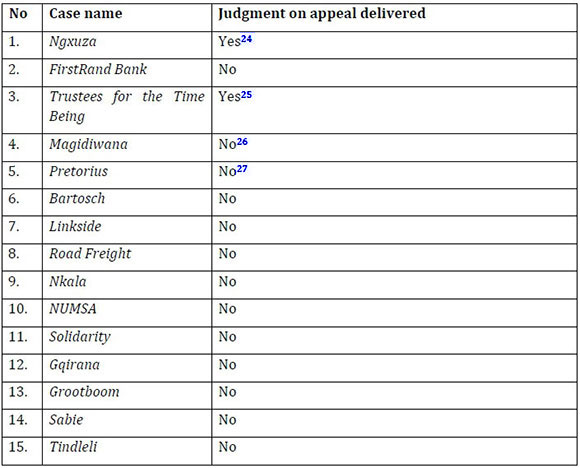

The Table below indicates the cases in respect of which judgments on appeal have been given in relation to the pronouncement on whether the matter could proceed as a class action:

3.11 Completed class action trials and success

The Table below indicates cases which, after the courts made pronouncements that they could proceed as class actions, culminated in completed class action trials, and whether the applicant(s) were successful:

4 ANALYSIS

4.1 Number of class actions and certification rate

It may be worth comparing the above data to the class action regimes of Ontario, Canada, and the United States. Apart from being regarded as the leaders in the field of class action litigation,30 their systems of civil procedure are also of common law origin and the adversary system of litigation is a characteristic of both of them. The basic principles that underlie these systems are similar.31 Both jurisdictions trace their origins to the unwritten practices of English Chancery. Today, however, class actions in these jurisdictions are largely creatures of statute and rule.32 The American class action is regulated by a comprehensive court rule that deals with class actions at a federal level.33

In Canada, the Ontario Class Proceedings Act of 1992, which is based largely on a comprehensive report delivered by the Ontario Law Reform Commission in 1982 and the recommendations contained therein, deals comprehensively with all aspects relating to class actions in Ontario.34 It provides for a general class action and regulates matters similar to those provided for in Rule 23 of the Federal Rules, but does so in much more detail. There are many similarities between these jurisdictions' class action mechanisms and the South African class action. The South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC) accordingly considered these jurisdictions in its Working Paper35and Report36 in which various recommendations related to the South African class action were made, including that the principles underlying class actions should be introduced by an Act of Parliament and the necessary procedures by rules of court.37The class action, as it was framed by the SALRC, was to a large degree modelled on the class action mechanisms in the above jurisdictions. Notwithstanding obvious differences between these jurisdictions, including socio-economic differences, it may accordingly be instructive to have regard to these jurisdictions for comparative purposes.

As mentioned, this article relates to judgments and orders handed down after 27 October 2000.38 The data indicates that there have only been 15 cases - less than one case per year over the course of more than 19 years - where a South African superior court made a definitive pronouncement39 on whether a matter could proceed as a class action and where it is clear from the judgment or order that the applicant(s) intended to frame the matter as a class action.

In the United States, with a population of approximately 330 000 00040 and where class actions have been authorised by courts for more than 50 years, approximately 12500 class actions are instituted annually.41 Data on the number of certifications in relation to the number of class action filings is, however, hard to come by and mostly outdated.42 Fitzpatrick states, more generally, that the data that currently exists on how the class action system in the United States operates, is limited.43

The position differs when compared to Ontario. It celebrated the 25th anniversary of its class action procedure in 2017 , ie 25 years after the 1966 birth of the modern US class action. It is worth bearing in mind that 2019 was the 25th anniversary of the introduction of South Africa's class action. In Ontario, however, approximately 1500 class actions were certified between 1993 and February 2018. Furthermore, in Ontario, more than 100 class actions are filed annually. Of all class actions filed per annum, more than 70 per cent are certified.44

There is no available data on the number of class actions instituted annually in South African superior courts.45 The author would nevertheless be surprised if there is any significant disparity between the number of class action certification applications and the number of certification judgments, irrespective of outcome, delivered annually. The latter data does, of course, form part of this study. The comparative data suggests that South Africa's class action is used rather infrequently when compared to foreign jurisdictions with comparable class action mechanisms, specifically Ontario and the United States. Numerous reasons could conceivably be advanced to explain the infrequent utilisation of the South African class action during the period concerned, including that the failure by the South African legislature to regulate the mechanism has resulted in it being viewed, and used, with caution. In this regard, most foreign jurisdictions with class action mechanisms regulate it by specially designed legislation or court rules.46 Locally, several scholars have called for specific class action legislation to be introduced in South Africa,47 which could ensure that the development of class action procedure does not depend entirely on our courts, and which could enable South Africa to follow in the footsteps of other countries with specific class action legislation.48At present, the development of the procedural framework within which the class action device operates is left entirely to our courts' discretion. Although they have performed commendably, this is an issue which merits further consideration and research.

It is interesting to note that, on average, 70 contested class actions in Ontario are certified annually, whereas in South Africa less than one certification judgment is delivered, on average, per annum, which includes judgments and orders where certification was refused. In fact, the data demonstrates that South African courts have, over the course of the past 19 years since the introduction of the certification requirement, only certified seven class actions. This means that, whereas the certification rate in Ontario is in excess of 70 per cent in South Africa approximately 0.37 per cent of class actions are certified annually.

The data further indicates that, in more than 50 per cent of cases where a South African superior court was requested to certify a class action, authorisation to proceed with class action proceedings was refused. The difference in certification success compared to Ontario where, as mentioned, more than two-thirds of class actions are certified annually, is significant. However, the fact that less than half of requests for certification of class action proceedings enjoy court authorisation, does not in itself justify a conclusion regarding whether the certification process functions appropriately. For example, the Law Commission of Ontario (LCO) has stated that the 73 per cent approval rate of contested certification motions could be interpreted to mean that the certification process favours plaintiffs and that reforms are necessary, or could be interpreted to mean that the certification approval rate proves that the current test is working appropriately. "Statistics alone, however, cannot answer the question of whether the certification test should be reformed. There is no simple or accepted statistical benchmark of what constitutes an appropriate certification rate."49

4.2 Increase in the incidence of class actions

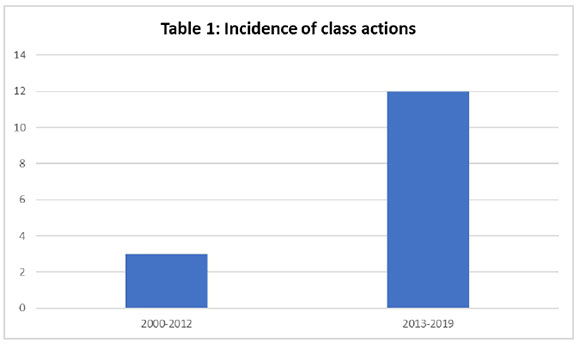

The data demonstrates that there were only three cases between 2000 and 2012 during which courts pronounced on whether class actions could proceed as such. However, as Table 150 below indicates, there were 12 such cases between 2013 and 2019.

Thus, if one compares the number of cases between 2001 and 2012 and the number of cases between 2013 and 2019, it becomes apparent that there was a significant (300 per cent) increase in the incidence of class actions from the first 13-year period to the next seven-year period. The data lends credence to the general perception that the South African class action landscape is a rapidly developing area of law.51 This increase is likely to be attributable, at least in part, to the legal certainty brought about by the judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeal in Children's Resource Centre Trust and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others52 (Children's Resource Centre Trust) insofar as class actions in South Africa are concerned.

In this judgment, which was delivered on 29 November 2012, the Court dealt with the circumstances when a class action may be instituted and the procedural requirements that must be satisfied before such proceedings may be instituted. It is also authority for the recognition of a class action outside the ambit of the Constitution.53Wallis JA also confirmed that the first procedural step prior to the issuing of summons is to apply to court to certify the process as a class action.54 He further laid down certification requirements which should guide a court in making its decision regarding the certification of a class action.55 Litigants and our courts are now presented with a clearer adjudicative framework within which the South African class action functions.

4.3 Types of issues

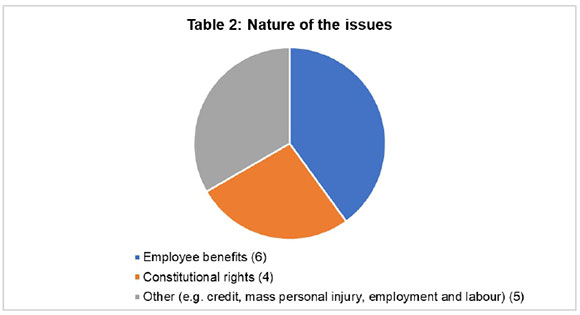

Table 2 below indicates the nature of the issues in respect of which the class action was sought to be used during the period covered by this article.

This article has categorised Nkala as a personal injury claim56 and Trustees for the Time Being as a competition claim.57 There have accordingly been no class action certification judgments handed down in respect of, for example, consumer, environmental, or securities or shareholder claims, and claims for loss of profit. According to the LCO, the approximately 1 500 class actions instituted in Ontario between 1993 and February 2018 covered a wide range of issues, including competition issues, consumer issues, employment and pension related claims, environmental claims, franchise issues, insurance, mass torts, privacy, professional negligence and product liability issues.58 The most frequent types of cases for which their class action is used are securities litigation (16%), followed by competition claims (15%) and product liability claims (15%).59 In the United States, statistics demonstrate that a variety of fields are covered by class action filings, but that the majority of class actions relate to securities and antitrust claims (approximately 30%), followed by labour and employment claims (approximately 15%), consumer claims (12%), employment benefits (10%), civil rights (10%), with the remainder comprising claims related to debt collection, antitrust, commercial and other issues.60

South Africa's class action has primarily been used in relation to employee benefit disputes (40%) and constitutional rights related disputes (27%). The data suggests that it has, to date, not really been used as a vehicle for litigating securities or shareholder claims, which is what the mechanism is mostly used for in the foreign jurisdictions referred to above. It is submitted that this serves to confirm that the primary purpose for which the mechanism is used in the South African context is to facilitate access to justice for vulnerable and marginalised individuals and to assist them to vindicate their rights, constitutional and otherwise.61

4.4 Opt-in, opt-out and bifurcation

The choice between the opt-in and opt-out class action regimes is a difficult one and has been subject to debate. Our courts have also not provided enough guidance on this issue. In opt-out class actions, individuals who fall within the class definition are automatically included in the class unless an individual affirmatively requests exclusion from the class. In other words, class members are provided with an opportunity to opt out if they do not wish to be part of the class action. Class members who do not opt out are bound by the outcome of the class action. Class members who choose to opt out are at liberty to pursue individual claims against the defendant.62

In an opt-in class action, individual class members who fall within the class definition must affirmatively request inclusion to form part of the class action. Class members who do not opt into the class action are not bound by its outcome and they will accordingly be at liberty to pursue individual claims against the defendant. Naturally, they will also forfeit the opportunity to share in the benefits obtained by the class in the event of a favourable judgment. Most foreign class actions operate on an opt-out basis, although the opt-in class action regime is utilised in a limited number of, primarily European, jurisdictions.63 The United States and Ontario subscribe to the opt-out class action regime for civil damages class actions.64

The data demonstrates a clear preference for certification of opt-out class actions. Close to two thirds of South African court-approved class actions were authorised to proceed as opt-out class actions. This is aligned with the trend in class action jurisdictions globally, as the opt-out class action regime is undoubtedly universally more popular than the opt-in class action regime.65 Only two out of seven court approved class actions were authorised on an opt-in basis and one class action was bifurcated into opt-out and opt-in phases.

The case in which a bifurcated approach was followed is Nkala, the first certified mass personal injury class action in South Africa. This is relevant because a personal injury class action presents unique challenges compared to other types of class actions, such as consumer class proceedings. In a personal injury class action, the extent of the injuries and the quantum of damages suffered by each member are individual issues and it may be necessary to determine those issues on an individual basis. To do so, the court may decide to sever the common issues from the individual issues for all class members in multiple stages of the same litigation, ie to bifurcate the procedure. According to Mulheron, the jurisdictions of Australia, Ontario and the United States all practise bifurcation or a similar form of splitting of the trial. It entails that the individual issues are resolved within the class action itself but in a phase of the litigation which is separate from the common issues trial.66

4.5 Settlement

The data demonstrates that, out of the seven judgments and orders in which court approval of the class action was given, there has only been one court approved settlement. The settlement relates to Nkala and is reported as Ex Parte Nkala.67

In the United States, according to Fitzpatrick, "[v]irtually all cases certified as class actions and not dismissed before trial end in settlement".68 Klement and Klonoff refer to a study of a representative sample of class actions from 2009 to 2013 in which the Israeli and US class action mechanisms were compared, where it was found that no cases ended in a final judgment on the merits, and only about one-third of the cases resulted in class-wide relief through settlement, which was below the national average for individual federal cases.69 It has further been found that, over a two year period in the United States, district court judges approved 688 class action settlements involving more than $33 billion.70 Federal court class settlements in 2006 and 2007 were found to average close to $55,000,000 while the median settlement was $51,000,000.71Compared to South Africa, the class action settlement industry in the United States is clearly thriving.

It is unsurprising that there has only be one court approved South African class action settlement. The first reason for it being unsurprising is the relatively recent judicial development of a more certain and comprehensive framework for the adjudication of class actions referred to above which has likely contributed to the recent increase in the incidence of class actions. Secondly, it was in the Nkala judgment that a court for the first time held that settlement agreements reached after certification are subject to court approval, otherwise they will be invalid.72 The latter judgment was only delivered on 13 May 2016.

4.6 Other observations

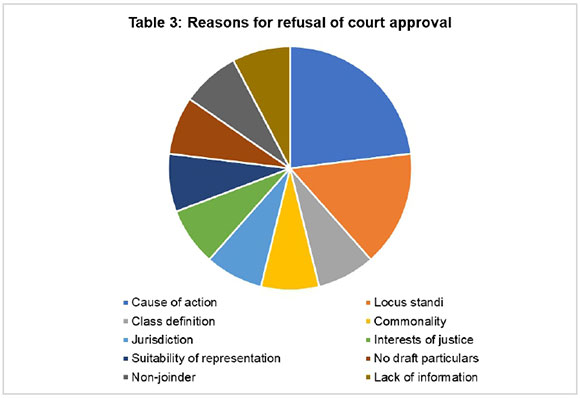

According to the collected data, in the eight cases where certification was refused, the primary reasons advanced for refusing to authorise class proceedings are a failure by the applicants to satisfy the court that there was a cause of action raising triable issues (23%) and a failure to prove that they possess the necessary locus standi (15%). The other reasons are indicated in the Table below:

The above grounds for refusing certification are aligned with the experiences of other jurisdictions with similar certification procedures. For example, the grounds typically advanced for refusing certification in Ontario vary between reasons related to the cause of action, whether there is an identifiable class, commonality, preferability,73and the existence of a representative plaintiff or defendant. The grounds mostly cited are lack of common issues, and failure to show that a class action is the preferable procedure.74

A further observation relates to the fact that only two judgments pertaining to the courts' decision whether to authorise class proceedings have resulted in judgments on appeal. On appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal, the judgment of Foreman J in Ngxuza was upheld.75 Two appeals emanated from the judgment in Trustees for the Time Being.

In Children's Resource Centre Trust,76the matter was referred back with leave given to supplement the papers to deal with the requirements for certification in class actions set out by the Supreme Court of Appeal in its judgment. In the second appeal, the Supreme Court of Appeal held that the applicants had not made out a case for an opt-in class action.77 The latter judgment was appealed to the Constitutional Court.78 In none of the appeals was a refusal to certify finding replaced by one authorising class proceedings.

The data further demonstrates that there have been two completed class action trials during the period covered by this article. In other words, less than 15 per cent of class actions in which a court was requested to authorise class action proceedings, culminated in a class action trial and was litigated to completion. It should also be noted that in one of these cases, Magidiwana, the primary reason for the matter culminating in completed trial proceedings was that the relief sought by the applicants and parts A and B of the notice of motion were of the same nature. The Court therefore only had to decide part A, which it did in the same judgment in which it confirmed certification of the class action. There was accordingly no lapse in time between the class action having been authorised and the subsequent class action trial, which meant that the scope to engage in class action settlement discussions was considerably less.

Finally, there are three interesting observations to make in relation to Linkside, which is the only other case which was litigated to completion. First, it is the first class action to be certified on an opt-in basis. Secondly, it is the only South African class action case in which certification was uncontested79 , and it is also the only class action successfully litigated to completion in which the applicants were successful.80

5 CONCLUSION

Class actions are likely to remain an important part of the South African civil justice system in future.81 The author has argued elsewhere that the importance of the mechanism in a South African context is underlined by its primary purpose , which is to facilitate the provision of access to justice.82 The mechanism is important "given the ravages of our past and the need for courts to act as vehicles for transformative social change".83 Our judges have therefore been encouraged to "embrace class actions as one of the tools available to litigants for placing disputes before them".84

However, De Vos warns that "judges will face a heavy task to develop this procedure to meet the exigencies of future events that trigger harm to large groups of people".85 It is submitted that, in developing the mechanism, our judges' task should be made easier by enabling them to have regard to available data to guide them in their decision making and to monitor its continued development. As mentioned, at present no such data exists. Hensler states as follows regarding the lack of available data concerning class actions in jurisdictions globally:

"Given the sharp and protracted controversy that has accompanied the introduction of class actions in virtually all jurisdictions, and the important concerns that have been raised about potential uses and abuses of collective litigation, one might expect that jurisdictions would be carefully tallying the frequency and circumstances in which class actions are filed and collecting systematic information about class action outcomes. Alas, that is not the case. To my knowledge, no jurisdiction publishes official statistics on the number of complaints filed in which plaintiffs seek to proceed collectively. No one knows how many class actions are filed annually in federal or state courts in the United States, much less the characteristics or outcomes of these cases."86

The South African class action can no longer be said to be embryotic. It has been part of the legal system for more than 25 years. However, as this article demonstrates, there have only been a limited number of certification judgments delivered to date. The data presented herein could accordingly place South Africa in the fortuitous position of being able to build a comprehensive data archive in which the class action is statistically dissected. Without comprehensive data concerning the operation of the mechanism, the available information will be insufficient in providing adequate insight to enable its optimal development going forward.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Du Plessis M, Oxenham J, Goodman I, Kelly L & Pudifin-Jones S (eds) Class action litigation in South Africa Claremont: Juta (2017). [ Links ]

Hodges C The reform of class and representative actions in European legal systems: a new framework for collective redress in Europe Oxford: Hart Publishing (2008). [ Links ]

Klonoff R H Class actions and other multi-party litigation in a nutshell 4th ed Minnesota: West Academic Publishing (2012). [ Links ]

Mulheron R The class action in common law legal systems : a comparative perspective . Oxford: Hart Publishing (2004). [ Links ]

Chapters in books

De Vos W "Conclusion" in Du Plessis M, Oxenham J, Goodman I, Kelly L & Pudifin-Jones S (eds) Class action litigation in South Africa Claremont: Juta (2017). [ Links ]

Martineau Y & Lang A "Canada" in Karlsgodt P G (ed) World class actions - a guide to group and representative actions around the globe Oxford: Oxford University Press (2012). [ Links ]

Unterhalter D & Coutsoudis A "Class actions and causes of action" in Du Plessis M, Oxenham J, Goodman I, Kelly L and Pudifin-Jones S (eds) Class action litigation in South Africa Claremont: Juta (2017). [ Links ]

Journal Articles

Bassett D L "The future of international class actions" (2011) 18 Sw J Int'lL 21. [ Links ]

Broodryk T "The South African class action vs group action as an appropriate procedural device" (2019) 1 Stell LR 6. https://doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a4506 [ Links ]

Broodryk T "The South African class action mechanism: comparing the opt-in regime to the opt-out regime" (2019) 22 PER / PELJ. https://doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a4506 [ Links ]

Cassim F & Sibanda O S "The Consumer Protection Act and the introduction of collective consumer redress through class actions" (2012) 75 THRHR 586. [ Links ]

De Vos W " 'N groepsgeding in Suid-Afrika" (1985) 3 TSAR 296. [ Links ]

De Vos W " 'N groepsgeding ('class action') as middel ter beskerming van verbruikersbelange" (1989) De Rebus 373. [ Links ]

De Vos W "Reflections on the introduction of a class action in South Africa" (1996) TSAR 639. [ Links ]

Erasmus H J "Civil procedural reform - modern trends" (1999) Stell L R 3. [ Links ]

Fitzpatrick B "An empirical study of class action settlements and their fee awards" (2010) 7:4 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2010.01196.x [ Links ]

Gericke E "Can class actions be instituted for breach of contract?" (2009) (2) THRHR 304. [ Links ]

Hensler D "From sea to shining sea: how and why class actions are spreading globally" (2017) Kansas Law Review 965. [ Links ]

Hurter E "Class action: failure to comply with guidelines by courts ruled fatal" (2010) 2 TSAR 409. [ Links ]

Hurter E "Some thoughts on current developments relating to class actions in South African law as viewed against leading foreign jurisdictions" (2006) 39(3) CILSA 485. [ Links ]

Hurter E "The class action in South Africa: quo vadis" (2008) 41(2) De Jure 293. [ Links ]

Klement A & Klonoff R "Class actions in the United States and Israel: a comparative approach" (2018) 19:1 Theoretical Inquiries in Law 151. https://doi.org/10.1515/til-2018-0006 [ Links ]

Marcin R B "Searching for the origin of class action" (1974) 23 Cath UL Rev 515. [ Links ]

Morabito V "Judicial supervision of individual settlements with class members in Australia, Canada and the United States" (2003) 38 Tex Int'l L J 663. [ Links ]

Legislation

Competition Act 89 of 1998.

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996.

Fire Brigade Services Act 99 of 1987.

Interim Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1993.

National Credit Act 34 of 2005.

Ontario Class Proceedings Act of 1992.

Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005.

Case law

Acton v Radebe NO 2014 JDR 1379 (WCC).

Bartosch v Standard Bank of South Africa Limited 2014 JDR 1687 (ECP).

Coetzee v Comitis and others 2001 (1) SA 1254 (C).

ECAAR SA & another v President of the RSA & others 2004 JDR 0593 (C).

E N and others v Government of RSA and others 2007 (1) BCLR 84 (D).

Ex parte Nkala 2019 JDR 0059 (GJ).

FirstRand Bank Ltd v Chaucer Publications (Pty) Ltd 2008 (2) All SA 544 (C).

Gqirana v Government Employees Pension Fund 2018 JDR 0199 (GP).

Grootboom v MEC: Department of Education, Eastern Cape Province 2019 JDR 0018 (ECG).

Highveldridge Residents Concerned Party v Highveldridge TLC and others 2003 (1) BCLR 72 (T).

Jenkins v Raymark Industries Inc 782 F 2d 468 (5th Cir 1986).

Lebowa Mineral Trust Beneficiaries Forum v President of the Republic of South Africa and others 2002 (1) BCLR 23 (T).

Linkside & others v Minister of Basic Education order (by agreement) by the High Court of South Africa, Eastern Cape Division, Grahamstown, dated 20 March 2014. Case number 3844/2013.

Linkside & others v Minister of Basic Education 2015 JDR 0032 (ECG).

Magidiwana and others v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (No 1) 2014 (1) All SA 61 (GNP).

Magidiwana and other injured and arrested persons v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (No 2) 2014 (1) All SA 76 (GNP).

Magidiwana and other injured and arrested persons and others v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (Black Lawyers Association as amicus curiae) 2013 (11) BCLR 1251 (CC).

Mazibuko and others v City of Johannesburg and others (Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions as amicus curiae) 2008 (4) All SA 471 (W).

McMullin v ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd (No 6) (1998) 84 FCR.

Mshengu and others v Msunduzi Local Municipality and others 2019 (4) All SA 469 (KZP).

Mukaddam and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others 2013(2) SA 254 (SCA).

Mukaddam v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (5) SA 89 (CC).

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa v Oosthuizen and others 2017 (6) SA 272 (GJ).

Ngxuza and others v Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape and others 2001 (2) SA 609 (E).

Nkala and others v Harmony Gold Mining Company Ltd and others (Treatment Action Campaign NPC and another as amici curiae) 2016 (3) All SA 233 (GJ).

Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape, and another v Ngxuza and others 2001 (4) SA 1184 (SCA).

Persons listed in Schedule "A" to the Particulars of Claim v Discovery Health (Pty) Ltd & others 2009 JDR 0087 (T).

Phumaphi v The African National Congress 2011 JDR 0401 (ECG).

Pretorius and another v Transnet Second Defined Benefit Fund and others 2014 (6) SA 77 (GP).

Pretorius and another v Transport Pension Fund and others 2018 (7) BCLR 838 (CC).

Rail Commuters Action Group and others v Transnet Ltd t/a Metrorail and others 2007 (1) All SA 279 (C).

Ramakatsa and others v Magashule and others 2013 (2) BCLR 202 (CC).

Road Freight Association v Chief Fire Officer Emakhazeni 2015 JDR 1802 (GP).

Sabie Chamber of Commerce and Tourism and others v Thaba Chweu Local Municipality and others; Resilient Properties Proprietary Limited and others v Eskom Holdings Soc Ltd and others (2295/2017, 83581/2017) 2019 ZAGPPHC 112 (7 March 2019).

Solidarity v Government Employees Pension Fund 2018 JDR 0312 (GP).

Stanford vJohns-Manville Sales Corp 923 F 2d 1142 (5th Cir 1991).

Tindleli and another v Government Employees Pension Fund 2019 JDR 0977 (GP).

Trustees for the Time Being of the Children's Resource Centre Trust & others v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Limited & others 2011 JDR 0498 (WCC).

Trustees for the Time Being of the Children's Resource Centre Trust v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd (Legal Resources Centre as amicus curiae) 2013 (1) All SA 648 (SCA).

Reports

South African Law Reform Commission The recognition of a class action in South African law Working Paper 57 Project 88 (1995). [ Links ]

South African Law Reform Commission The recognition of class actions and public interest actions in South African law Report Project 88 (1998). [ Links ]

Law Commission of Ontario Class actions: objectives, experiences and reforms: final report (2019). [ Links ]

Walker J Class proceedings in Canada - report for the 18th Congress of the International Academy of Comparative Law (2010). [ Links ]

Internet sources

South African judiciary 2018/2019 annual report available at https://www.judiciary.org.za/index.php/documents/judiciary-annual-reports (accessed 15 November 2019). [ Links ]

United States Census Bureau available at https://www.census.gov/popclock/ (accessed 16 November 2019). [ Links ]

Theses

De Vos W Verteenwoordiging van groepsbelange in die siviele proses (unpublished LLM dissertation, RAU, 1985). [ Links ]

1 Erasmus H J "Civil procedural reform - modern trends" (1999) Stell L R 1 at 18. According to the 2018/2019 South African Judiciary Annual Report, in relation to the "[p]erformance of the Superior Courts for the period April 2018 - March 2019" the "percentage of civil cases finalised by the High Court" amounted to 114 650 cases, out of a total of 145 127 cases. See South African Judiciary 2018/2019 Annual Report available at https://www.iudiciary.org.za/index.php/documents/iudiciary-annual-reports (accessed 15 November 2019).

2 Section 7(4)(b)(iv) of the Interim Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1993, the equivalent of s 38(c) of the final Constitution of the Republic of South Africa,1996.

3 For example, the article will not measure the distribution of class action proceeds to legal representatives vis- a- vis class members, the litigation funding regimes employed in the reported cases, the average time it takes between instituting class ac proceedings and the delivery of certification judgments or orders, the degree of judicial case management employed in certified class action proceedings, and so forth.

4 In the form of a written judgment or order.

5 Each judgment or order in respect of the cases which form part of this article contains one or more of the following words: 'certify', 'certification' and/or the words 'prior' and 'leave' in close proximity. These words are used in the context of determining whether to authorise the continued conduct of class action proceedings.

6 See the definition of 'class action' by Mulheron R The class action in common law legal systems: a comparative perspective Oxford: Hart Publishing (2004) at 3, quoted with approval in Trustees for the time being of the Children's Resource Centre Trust v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd (Legal Resources Centre as amicus curiae) 2013 (1) All SA 648 (SCA) at para 16: " A class action is a legal procedure which enables the claims (or parts of the claims) of a number of persons against the same defendant to be determined in the one suit. In a class action, one or more persons ('representative plaintiff) may sue on his or her own behalf and on behalf of a number of other persons ('the class') who have a claim to a remedy for the same or a similar alleged wrong to that alleged by the representative plaintiff, and who have claims that share questions of law or fact in common with those of the representative plaintiff ('common issues'). Only the representative plaintiff is a party to the action. The class members are not usually identified as individual parties but are merely described. The class members are bound by the outcome of the litigation on the common issues, whether favourable or adverse to the class, although they do not, for the most part, take any active part in that litigation."

7 2001 (2) SA 609 (E).

8 Judgment was handed down on 27 October 2000 and is included for the purpose of this article.

9 At 624-D-E, Froneman J held as follows: "But I also think that the possibility of unjustified litigation can be curtailed by making it a procedural requirement that leave must be sought from the High Court to proceed on a representative basis prior to actually embarking on that road. This Division does not at present have practice directions to that effect nor am I aware of any such directions in other Divisions, but it is certainly an issue that I hope will receive attention soon." Certification is now a formal procedural requirement: see FirstRand Bank Ltd v Chaucer Publications (Pty) Ltd 2008 (2) All SA 544 (C) at para 26 and Trustees for the time being of the Children's Resource Centre Trust and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others (Legal Resources Centre as amicus curiae) 2013 (3) BCLR 279 (SCA) at para 23.

10 See Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape, and another v Ngxuza and others 2001 (4) SA 1184 (SCA).

11 De Vos (2017) at 243.

12 This article reflects the position as at 15 November 2019.

13 In the form of a written judgment or order.

14 See fn 5 above.

15 See fn 6 above.

16 Where the damages suffered by class members have to be determined, it is generally necessary for individual evidence to be given by each class member. It may therefore be necessary to sever the common issues from the individual issues for all class members at multiple stages of the same litigation. This is typically referred to as bifurcation. According to Mulheron (2004) at 261, the jurisdictions of Australia, Ontario and the United States all practise bifurcation or a similar form of splitting of the trial. It entails that the individual issues are resolved within the class action itself but at a phase of the litigation which is separate from the common-issues trial. See, for example, McMullin v ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd (No 6) (1998) 84 FCR at 1-2, where judgment on liability was delivered, whereafter certain damages claims were heard and determined by judges and some were heard and determined by a judicial registrar. See also See Nkala and others v Harmony Gold Mining Company Ltd and others (Treatment Action Campaign NPC and another as amici curiae) 2016 (3) All SA 233 (GJ) at paras 116-125.

17 Success being measured on a conspectus of considerations, including the relief sought and the judgment delivered following trial proceedings.

18 The Southern African Legal Information Institute.

19 Du Plessis M, Oxenham J, Goodman I, Kelly L & Pudifin-Jones S (eds) Class action litigation in South Africa 2017.

20 It should be noted that there were several cases that were initially identified but, upon closer inspection, were excluded because they did not meet the criteria. In this regard, cases initially considered, but thereafter excluded include: Coetzee v Comitis and others 2001 (1) SA 1254 (C); Lebowa Mineral Trust Beneficiaries Forum v President of the Republic of South Africa and others 2002 (1) BCLR 23 (T); Highveldridge Residents Concerned Party v Highveldridge TLC and others 2003 (1) BCLR 72 (T); ECAAR SA & another v President of the RSA & others 2004 JDR 0593 (C); E N and others v Government of RSA and others 2007 (1) BCLR 84 (D); Rail Commuters Action Group and others v Transnet Ltd t/a Metrorail and others 2007 (1) All SA 279 (C); Mazibuko and others v City of Johannesburg and others (Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions as amicus curiae) 2008 (4) All SA 471 (W); Persons listed in Schedule "A" to the Particulars of Claim v Discovery Health (Pty) Ltd & others 2009 JDR 0087 (T); Phumaphi v The African National Congress 2011 JDR 0401 (ECG); Ramakatsa and others v Magashule and others 2013 (2) BCLR 202 (CC); Acton v Radebe NO 2014 JDR 1379 (WCC); Mshengu and others v Msunduzi Local Municipality and others 2019 (4) All SA 469 (KZP).

21 A copy of the order is on file with the author.

22 Unterhalter D & Coutsoudis A "Class actions and causes of action" in Du Plessis M, Oxenham J, Goodman I, Kelly L & Pudifin-Jones S (eds) (2017) 53.

23 Settlement reported at: Ex parte Nkala 2019 JDR 0059 (GJ).

24 Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape, and another v Ngxuza and others 2001 (4) SA 1184 (SCA).

25 Children's Resource Centre Trust and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (2) SA 213 (SCA); Mukaddam and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (2) SA 254 (SCA); Mukaddam v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (5) SA 89 (CC).

26 See, however, Magidiwana and Other Injured and Arrested Persons and others v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (Black Lawyers Association as amicus curiae) 2013 (11) BCLR 1251 (CC). See also Magidiwana and Other Injured and Arrested Persons v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (No 2) 2014 (1) All SA 76 (GNP).

27 See, however, Pretorius and another v Transport Pension Fund and others 2018 (7) BCLR 838 (CC).

28 Magidiwana and others v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (No 1) 2014 (1) All SA 61 (GNP), upheld in Magidiwana and Other Injured and Arrested Persons and others v President of the Republic of South Africa and others (Black Lawyers Association as amicus curiae) 2013 (11) BCLR 1251 (CC).

29 See Linkside & others v Minister of Basic Education 2015 JDR 0032 (ECG).

30 Bassett D L "The future of international class actions" (2011) 18 Sw J Int'l L 21 at 22-24.

31 De Vos W "'N groepsgeding in Suid-Afrika" (1985) 3 TSAR 296 at 304. Hurter E "Class action: failure to comply with guidelines by courts ruled fatal" (2010) 2 TSAR 409 at 413 states that the class action is effectively an American phenomenon and that other Anglo-American jurisdictions that have opted for formal class action devices have been influenced by the American class action. According to Hurter, it is clear that South African class action developments mirror this trend.

32 Marcin R B "Searching for the origin of class action" (1974) 23 Cath UL Rev 515 at 517.

33 Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 governs class actions in federal courts. Rule 23 makes provision for three categories of class actions: Rule 23(b)(1) provides for two types of so-called "prejudice" class actions; Rule 23(b)(2) provides for declaratory and injunctive relief; and Rule 23(b)(3) provides for the opt-out damages class action. The most important of these categories are class actions to obtain declaratory or injunctive relief and actions for damages. According to Klonoff R H Class actions and other multi-party litigation in a nutshell 4 ed Minnesota: West Academic Publishing (2012) at 75, most class actions are brought and certified under Rules 23(b)(2) and 23(b)(3). Rule 23(b)(1) is used less frequently. Further, according to Hodges C The reform of class and representative actions in European legal systems: a new framework for collective redress in Europe Oxford: Hart Publishing (2008) at 135, the majority of the rules that regulate class actions in America are based on an opt-out rather than an opt-in mechanism.

34 According to Martineau Y & Lang A "Canada" in Karlsgodt P G (ed) World class actions - a guide to group and representative actions around the globe (2012) 57, with the exception of the province of Quebec, which is a civil law jurisdiction, all Canadian provinces and territories are common law jurisdictions.

35 South African Law Commission The recognition of a class action in South African law Working Paper 57 Project 88 (1995). At the time it was known as the South African Law Commission. It became the South African Law Reform Commission in 2002.

36 The South African Law Reform Commission The recognition of class actions and public interest actions in South African law report Project 88 (1998).

37 The South African Law Reform Commission (1998) at para 5.6.5.

38 Until 15 November 2019. The article accordingly considers class actions over a period in excess of 19 years.

39 For the sake of convenience, this article will forthwith refer to "certify" and/or "certification", which reference includes those judgments where reference to the words "prior" and "leave", in close proximity to one another, were made.

40 United States Census Bureau available at https://www.census.gov/popclock/ (accessed 16 November 2019).

41 Klement A & Klonoff R "Class actions in the United States and Israel: a comparative approach" (2018) 19:1 Theoretical Inquiries in Law 151 at 152 & 189-190.

42 Klement & Klonoff (2018) at 191.

43 Fitzpatrick B "An empirical study of class action settlements and their fee awards" (2010) 7:4 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 811 at 812.

44 Law Commission of Ontario Class actions: objectives, experiences and reforms: final report (2019) at 5.

45 See fn 1 above.

46 Karlsgodt P G "United States" in Karlsgodt P G (ed) World class actions - a guide to group and representative actions around the globe (2012).

47 See inter alia De Vos W Verteenwoordiging van groepsbelange in die siviele proses (unpublished LLM dissertation, RAU , 1985); De Vos (1985) at 296; De Vos W "'N groepsgeding ('class action') as middel ter beskerming van verbruikersbelange" (1989) De Rebus 373 at 373; De Vos W "Reflections on the introduction of a class action in South Africa" (1996) TSAR 639 at 639; Hurter E "Some thoughts on current developments relating to class actions in South African law as viewed against leading foreign jurisdictions" (2006) 39(3) CILSA 485 at 485; E Hurter "The class action in South Africa: quo vadis" (2008) 41(2) De Jure 293 at 293; Gericke E "Can class actions be instituted for breach of contract?" (2009) (2) THRHR 304 at 304.

48 Cassim F & Sibanda O S "The Consumer Protection Act and the introduction of collective consumer redress through class actions" (2012) 75 THRHR 586 at 587-588.

49 Law Commission of Ontario (2019) at 7.

50 All graphs and charts in this article are the author's constructs.

51 Du Plessis M "Class action litigation in South Africa" in Du Plessis M, Oxenham J, Goodman I, Kelly L & Pudifin-Jones S (eds) (2017) 3.

52 Children's Resource Centre Trust and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (1) All SA 648 (SCA) (Childrens Resource Centre Trust).

53 Children's Resource Centre Trust at para 21.

54 Children's Resource Centre Trust at paras 23-25.

55 Children's Resource Centre Trust at para 2 6.

56 Unterhalter & Coutsoudis (2017) at 54.

57 Unterhalter & Coutsoudis (2017) at 53.

58 Law Commission of Ontario (2019) at 5.

59 Law Commission of Ontario (2019) at 15.

60 Klement & Klonoff (2018) at 152 & 190-191.

61 See Broodryk T "The South African class action vs group action as an appropriate procedural device" (2019) 1 Stell LR at 6-32, where the author states as follows regarding the importance of the class action mechanism to facilitate access to justice: " A central theme in this article has been the importance of access to justice, and how it could serve as the foundation for the incorporation of the class action into South African law. It is essentially against this background that a court should decide on the appropriateness of class proceedings as a means of adjudicating the claims of class members. Our courts' assessment should be aimed at establishing whether certification of a class action is necessary to achieve access to justice. This includes considering whether any possible barriers exist and whether certification is necessary to overcome such barriers."

62 See Broodryk T "The South African class action mechanism: comparing the opt-in regime to the opt-out regime" (2019) 22 PER / PELJ.

63 See also Morabito V "Judicial supervision of individual settlements with class members in Australia, Canada and the United States" (2003) 38 Tex Int'l L J 663 at 671. See also Hensler D "From sea to shining sea: how and why class actions are spreading globally" (2017) Kansas Law Review 965 at 970.

64 Section 9 of the Class Proceedings Act, 1992, S.O. 1992, c 6. See also Walker J Class proceedings in Canada - Report for the 18th Congress of the International Academy of Comparative Law (2010). See also Hensler (2017) at 974.

65 Hensler (2017) at 974.

66 Mulheron (2004) at 261. See also, for example, McMullin v ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd (No 6) (1998) 84 FCR 1, 2 where judgment on liability was delivered, whereafter certain damages claims were heard and determined by judges and some were heard and determined by a judicial registrar. Split trials have also been endorsed under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules in respect of mass torts: see Stanford v Johns-Manville Sales Corp 923 F 2d 1142 (5 Cir 1991); asbestos claims: Jenkins v Raymark Industries Inc 782 F 2d 468 (5 Cir 1986).

67 Ex Parte Nkala 2019 JDR 0059 (GJ).

68 Fitzpatrick (2010) at 812.

69 Klement & Klonoff (2018) at 192.

70 Fitzpatrick (2010) at 845.

71 Klement & Klonoff (2018) at 192.

72 Nkala v Harmony Gold Mining Company Limited 2016 3 All SA 233 (GJ) at para 39: "We hold that it is in any event correct that any settlement agreement reached after certification of the class action should be subject to the approval of the court and that it should only be valid once approved by the court. This is to ensure that the settlement reached is fair, reasonable, adequate and that it protects the interests of the class."

73 This criterion is comparable to the South African certification factor that the class action must be the appropriate mechanism to adjudicate the dispute. For a comparative analysis, see Broodryk (2019) at 6-32.

74 Law Commission of Ontario (2019) at 17.

75 Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape, and another v Ngxuza and others 2001 (4) SA 1184 (SCA).

76 2013 (2) SA 213 (SCA).

77 Mukaddam and others v Pioneer Food (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (2) SA 254 (SCA).

78 Mukaddam v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (5) SA 89 (CC). The Constitutional Court upheld the appeal and ordered that the "orders of the high court and the Supreme Court of Appeal are set aside and replaced with the following order: '(a) Should the applicant pursue certification in the high court, he is granted leave to supplement his papers within two months of this order, by delivering supplementary affidavits to which a draft set of particulars of claim will be attached, setting out his claim against the respondents. (b) The respondents may deliver answering affidavits within a month from the date of delivery of affidavits referred to in (a). (c) The applicant may deliver his reply, if any, within two weeks from the date he receives affidavits referred to in (b). (d) The costs of the application are reserved.'"

79 The certification order was made by agreement.

80 Linkside & others v Minister of Basic Education 2015 JDR 0032 (ECG).

81 De Vos (2017) at 245 & 251.

82 Broodryk (2019) at 24-28. See also The South African Law Commission (1998) at paras 1.3-1.4; and the South African Law Commission (1995) at para 5.28 where it is stated that "[t]he whole purpose of class actions is to facilitate access to justice for the man on the street". See also Permanent Secretary, Department of Welfare, Eastern Cape v Ngxuza 2001 (4) SA 1184 (SCA) at para 1 where Cameron JA states that "[t]he law is a scarce resource in South Africa. This case shows that justice is even harder to come by. It concerns the ways in which the poorest in our country are to be permitted access to both". In Mukaddam v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd 2013 (2) SA 254 (SCA) at para 11 it is stated that "[t]he justification for recognising class actions is that without that procedural device claimants will be denied access to the courts". In Mukaddam v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd 2013 (5) SA 89 (CC) at para 29 Jafta J stated that "[a]ccess to courts is fundamentally important to our democratic order. It is not only a cornerstone of the democratic architecture but also a vehicle through which the protection of the Constitution itself may be achieved".

83 Du Plessis (2017) at 13.

84 Mukaddam v Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd and others 2013 (5) SA 89 (CC) at para 61.

85 De Vos (2017) at 251.

86 Hensler (2017) at 985.