Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.20 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v20i1.9

ARTICLES

Formation of a government in Lesotho in the case of a hung parliament

Hoolo 'Nyane

Public Law Lecturer, National University of Lesotho, Lesotho

1 INTRODUCTION

Although the question of the formation of a government has generated a lot of interest amongst constitutional and political scholars elsewhere,1 in Lesotho it has never really been much of a constitutional controversy, at least practically, since independence. The main reason has been that due to the constituency based electoral system which the country has been using since independence,2 only one political party has always been able to garner a sufficient majority to form the government,3 and the leader thereof would easily be invited to form government without any controversy. The conventional principle governing formation of government has always been straightforward - that the King would invite the leader of the political party or coalition of parties that appears to command the majority in the National Assembly to form the government.4 Most of the time, the matter would have been easily decided by the election.5 The introduction of the mixed electoral system with a strong proportionality element6 did not only bring about a paradigm shift from a dominant party system to inclusive politics, but also a new phenomenon of inconclusive elections which produce hung parliaments. This consequently came with some uncertainties about the process of formation of government. The mixed electoral system was first used in Lesotho in the remedial election of 2002,7 but since the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) garnered a sufficient majority to continue with government,8 the process was still not much of a controversy. The same applied to the 2007 election when the country used the mixed model for the second time. Matters came to a head in 2012 when the system was used for the third time. The continuity of the LCD in power was broken by the indecisive electoral outcome. Parties were then forced into negotiating political coalitions to enable them to collect sufficient numbers to form a government.9 For the first time since independence, the conventional principles on formation of a government were put to real test. Section 87 of the Constitution of Lesotho which embodies the convention on the formation of government was less helpful. The situation of hung parliament recurred in the 2015 snap election. With the prospect of a hung parliament being the recurrent feature of politics in Lesotho due to the mixed electoral system,10 the purpose of this article is to extrapolate the constitutional conventions governing the formation of government in general, and during hung parliament in particular. The article also makes recommendations for reform on how the operation of these constitutional conventions could be strengthened in order to attain the full objects of constitutional democracy, and to avoid uncertainty and potential unrest. The analysis is based largely on British constitutional conventions relating to the formation of a government and how they have been reduced to writing in the Constitution of Lesotho.

2 GENERAL PRINCIPLES UNDERPINNING THE FORMATION OF A GOVERNMENT IN LESOTHO

The process of government formation in Lesotho is not an abstract political process detached from the general principles undergirding constitutional design in the country. It is, like all the precepts of this design, based on the three major linchpins of constitutional theory in Lesotho. As a largely British based constitutional prototype, the Constitution of Lesotho is democratic, parliamentary and monarchical.11 This trilogy does not only underpin the formation of a government in Lesotho but is also the basis of its operation. On the first principle of democracy, section 1(1) of the Constitution establishes Lesotho as a "sovereign democratic state". Section 2 further provides that the Constitution is the supreme law of the land. So the confluence of these two sections, read together, establishes the Kingdom as not only a democracy but a constitutional one. In accordance with the democracy principle, section 20 of the Constitution gives every citizen of Lesotho right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives and to vote or stand for election. The section establishes both representative12 and direct democracy. So the formation of government follows the democracy principle which is realized through the medium of parliament.13 As Jennings, writing about the British constitution, poignantly contends: "according to the pretty schematization of the textbooks, the member of parliament represents a majority of the electors; government is responsible to a majority of the House of Commons; and the government thus represents a majority of the electors."14

So there is a triangular relationship between the elector, the parliament and the resultant government. The principle applies with equal measure to the workings of the Constitution of Lesotho. Government in Lesotho is finally based on the broader will of the electorate expressed through the doctrine of representation in parliament. So, in essence no government in Lesotho can legally form if it offends this fundamental theoretical postulation.

The second rudimental aspect of constitutional theory in Lesotho is that government is parliamentary. While it is not the enterprise of parliament to govern, as that is the province of the Prime Minister and Cabinet,15 the Parliament in Lesotho provides the parental nexus to the executive. Under the Constitution, both the executive and legislature overlap in a manner somewhat inimical to separation of powers as practised in pure presidential systems. Members of the executive, both the Prime Minister and the entire Cabinet, are drawn from either of the two chambers of Parliament16 and remain as such.17 Each member of the executive is both a law maker and government minister. Therefore there is a fusion of both. In that way, Parliament is the linchpin of Lesotho's Constitution. As Grant opines about the British Parliament, "it is the principal democratic heart of the political system".18 So in terms of the Constitution, no government can form in Lesotho without Parliament. Parliament gives both life and parentage to government in Lesotho.

The third principle which is equally important in the trilogy is that despite it being exalted as democratic, the constitutional system in Lesotho is also monarchical. This doctrine of constitutional monarchism does not only subject the monarch to the postulates of the Constitution,19 but also retains the monarch as the centripetal institution of the design. Even during the process of the formation of a government, the monarch is still very key. The monarch in Lesotho is not only the indivisible head of the three branches of government -the executive,20 the legislature21 and the judicature22 - but is also the one who appoints the government. This is one area of the Lesotho Constitution where traditional conceptions of government neatly coincide with the received conceptions of constitutional monarchy.23 By British convention, it is the prerogative of the sovereign to appoint the government.24

3 THE CHOICE OF A PRIME MINISTER AND FORMATION OF A GOVERNMENT

The choice of Prime Minister in Lesotho is based on British convention25 which has since been legislated under section 87(2) of the Constitution of Lesotho. Upon the drafting of the independence constitution, not only in Lesotho, but across the whole of Commonwealth Africa and the Caribbean, one of the most nagging questions has been the translation of British constitutional conventions - unwritten as they are in origin - into written constitutions.26 The greatest challenge has been brought about by the temptation, at independence, to reduce the originally unwritten conventions into the written constitutions of the newly independent nations. This dilemma was underscored by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Adegbenro v Akintola,27wherein Lord Bryce opined that the British Constitution "works by a body of understandings which no writer can formulate". This notwithstanding, the independence Constitution of Lesotho codified the British conventions on the fundamental structure and functioning of government.28 The 1993 Constitution became just the mirror image of the independence constitution on the fundamental structures and functioning of government. This strong colonial content in the Constitution of Lesotho is not in keeping with the pattern of constitutions that emerged in Africa in the early 1990s.29These constitutions sought to be creative by placing primacy on liberal notions such as human rights, oversight institutions and separation of powers.

Despite the difference in historical evolutions of parliament in Britain and the colonial parliament in Lesotho, the country has tenaciously retained the British structure of government. Thus, it has become important that in order to properly understand the provisions of the Constitution of Lesotho, the nature of the conventions upon which they are based must also be properly understood. However, that does not negate the fact that the Constitution of Lesotho is written and that the meaning of its clauses must be realised. Where it departs from British convention, the principle of constitutional supremacy dictates that the written text of the Constitution shall prevail.

Government in Lesotho, starting with its formation, turns on the office of Prime Minister.30 However, because of the general principles extrapolated above, the choice of the Prime Minister is not directly from the electorate - voters in Lesotho do not elect the Prime Minister, at least not directly. It is the prerogative of the monarch. This is a conventional rule inherited from British constitutional history.31Although the position of Prime Minster came to be so central to the formation and functioning of government at Westminster, it is a fairly modern institution traceable merely to the 18th century. According to one British authority, "...it was brought out by the combination of a number of factors including royal confidence, preeminence among ministers, patronage as First Lord of the Treasury, and especially control of commons."32

The position became firmly consolidated in the latter part of the 19th century as a direct product of the ascendency of representative democracy and its corollaries like the development of the political party system. Thus, being the successor to the office of the First Lord of the Treasury, the position owes its origin and existence to the prerogative of the monarch. In Lesotho the position of Prime Minister is even newer having been introduced only in 1965 as part of the Westminster constitutional conceptions transplanted to Lesotho in the run-up to independence. The Constitution of Lesotho has only codified the British constitutional conventions on the question of the choice of Prime Minister as follows: "The King shall appoint as Prime Minister the member of the National Assembly who appears to Council of the State to be the leader of the political party or coalition of political parties that will command the support of a majority of the members of the National Assembly."33

What is notable is that the section has slightly changed from its original formulation at independence. The independence constitution did not have the requirement of the "advice of the Council of State" which arguably rendered it closer to the classic British royal prerogative. In fact , in terms of the independence constitution of Lesotho the power to appoint the Prime Minister was one of the many discretionary powers of the King.34 In terms of constitutional parlance, these were the powers of the King which he exercised "in accordance with his own deliberate judgment".35 These powers hardly exist under the current constitutional design - all the powers of the King are now subject to advice either from Prime Minister,36 Council of State37 or other government institution.38

Be that as it may, the general principle remains intact - the choice of the Prime Minster is the prerogative of the King not the Council of State or the National Assembly. The two are only procedural limitations on the discretion of the King to appoint the Prime Minster. Nevertheless, as a result of the ascendancy of constitutional monarchism and the development of the party system, the convention has consolidated at Westminster that governments hold office by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of the House.39 Section 87(2) of the Constitution of Lesotho is by and large based on this convention. The convention presents a democratic limitation on the King's prerogative to appoint the Prime Minister. In terms of this convention, the Prime Minster must at all material times command the confidence of the National Assembly. This is the golden rule of a parliamentary democracy irrespective of whether the election produces a clear majority for one party or a hung parliament.40

The use of the words "who appears" in section 87(2) has generated a lot of controversy. The concept has its origins at Westminster. What it actually means is that there is no vote that is necessary for the choice of Prime Minster. The fundamental principle is that the King remains the final arbiter in the continuum; however, the King's judgment can no longer be absolute as it used to be in history.41 In making his judgment the King is guided by the convention that the person he appoints should "appear" to him to enjoy the confidence of the House. Bogdanor captures this convention much more aptly, in that "the sovereign's responsibility is confined to that of appointing as Prime Minister the person who is most likely to enjoy the confidence of the Commons".42 This section has been a subject of judicial determination in the case of Ntsu Mokhehle v Molapo Qhobela and Others.43 In casu, Ntsu Mokhehle, who was the Prime Minister of Lesotho since 1993, and leader of the Basotho Congress Party (BCP) since its formation in the early 1950s, had fallen out of favour with his own executive committee which in turn organised a party conference to remove him as party leader. At the time it was not clear both to him and his executive committee, what his status as Prime Minister would be if he were to be removed as party leader. His own view was that being party leader is conditio sine quo non for the office of Prime Minister. The Court made a clear distinction between the two - it held that the Prime Minister is the creature of the National Assembly. Members of the National Assembly are empowered to vote for the Prime Minister and vote him out.44 The Court held:

It is clear from the above that in all the happenings in parliament, the BCP as a political unit does not feature prominently. Its members are recognised by the Constitution as individuals despite the use of the term political party in the Constitution as individuals in the Constitution... The party does not feature by law in the making or unmaking of the Prime Minister.45

The operation of this principle in Lesotho had been fairly straightforward until 2012 when the election for the first time produced no clear majority for a single party in Parliament. This rule has a double-pronged rationale - first, the King has to make sure that the person he appoints will form a stable and effective government.46Secondly, it accords with the principle of democracy which in a way has diluted the purity and absoluteness of the classic prerogatives of the King. So the government that is formed must resonate with the general will of the people as represented by Parliament. Jennings adroitly captures the democracy principle thus:

The extension of the franchise, the attainment of a large measure of freedom of speech, and the organisation of parties, have created the modern Constitution. The House of Commons and the Cabinet are the instruments of democracy. The prerogative of the Crown and, to a less degree, the powers of the aristocracy, have been subordinated to public opinion.47

This postulation arguably applies with equal measure to the constitutional design in Lesotho. Another limitation in the new design is that the King's power of making a judgment has shifted to the Council of State. The Council of State is the successor to the erstwhile Privy Council which was the advisory body to the King under the Lesotho 1966 Constitution. The primary purpose of the newfound Council of State is 'to assist the King in the discharge of his functions'.48 Mahao contends that the exercise of residual powers by the King is one area where the 1993 Constitution of Lesotho is not identical with the Westminster design. He contends that "whatever residual prerogative vests in the King in Lesotho under the constitution [it] can only be exercised on the advice of the Council of State".49 It therefore suggests that the King has no individual discretion under the 1993 Constitution.50 The major criticism against the Council of State is that its structure is not balanced - it favours the executive or the Prime Minister who is a member himself. The majority of its members are largely ex officio people who in one way or another are appointed by the Prime Minister in their various designations.51 In that sense, it can safely be argued that the introduction of the Council of State to the constitutional design of Lesotho served more to emasculate the powers of the King and shifted them more towards the Prime Minister.52

Thus, according to this new design, it is the Council of State that makes the de facto judgment on who should be appointed as the Prime Minister. The temptation of pushing this responsibility of making the judgment to the Speaker of the National Assembly offends the spirit of this constitutional convention. The current challenge to the constitutional design in Lesotho is that the Council of State, although it came to cushion the King from political decisions and their implications, would seem to have rendered the King entirely titular.

4 A HUNG PARLIAMENT AND THE PROCEDURAL ASPECTS OF GOVERNMENT FORMATION

The centrepiece of Lesotho's system of government as a Westminster design is that the government of the day must enjoy the confidence of the National Assembly.53 In Lesotho, members of parliament are elected at the general election for a maximum term of five years. Commonly, one party has a majority of seats in the National Assembly, and such party forms a government smoothly in terms of section 87 (2) of the Constitution. However, both the 2012 and 2015 general elections produced a result in which no party had a majority of members in the National Assembly. This is known as a "hung Parliament".54 The general principles of parliamentary democracy articulated above apply mutatis mutandis to the formation of a government irrespective of whether the parliament is "hung" or there is a clear majority for one party. As Bogdanor contends: "A hung parliament merely makes transparent the fundamental principle of parliamentary government, a principle which has often been covert since 1868: a government depends upon the confidence of Parliament."55

Section 87(2), which enshrines the golden rule of formation of a government, anticipates that a government in Lesotho can be formed by the leader of the political party or coalition of political parties that will command the support of a majority of the members of the National Assembly. Lesotho has no established experience and precedent with hung parliaments largely because of the constituency based electoral system that tends to invariably produce a single party majority in Parliament.56 The 2012 elections experience was the first, and was not handled with procedural clarity that developed the precedent that could be recommended for the succeeding situations of hung parliament. In 2012, after the declaration of the results, it became clear that the then Prime Minister, Pakalitha Mosisili, through his newly founded Democratic Congress (DC) only secured 40 per cent of both the total national vote and of the seats in the National Assembly.57 Immediately, the leaders of the All Basotho Convention (ABC), LCD and Basotho National Party (BNP) hurriedly went to a press conference to announce their intention to form a coalition government.58 They even wrote a letter to the King informing him about their intention. At the same time, the DC was busy still bargaining with other parties, including the ones that had gone public about their intention to form government. DC even threatened to form a minority government in case it did not succeed in putting together a majority coalition . At that time the 14th day period provided for by the Constitution59 between the election and the convening of new Parliament had not yet lapsed. The situation nearly turned ugly as there were even media threats to prospective members of parliament should they vote for one camp and not the other. That chaotic situation was resolved by the first meeting of parliament. In terms of the Constitution, the first business of Parliament is to elect the Speaker and Deputy Speaker.60 Thus, when the parties went to the first sitting of parliament, there was still a lot of uncertainty on how the alliances really stood. The provisional coalition of ABC, LCD and BNP had candidates for both the positions of Speaker and Deputy Speaker, and the DC also had its candidates. The outcome was that the ABC alliance won the vote for the Speaker.61 However, the number of votes was greater than the total number of the members of parliament of three coalescing parties,62 which suggested that there was support from the smaller political parties which had consolidated themselves into a third force styled "Bloc".63 It was after that vote that the DC effectively surrendered, and that was the time when the public and probably the Council of State got a sense of who would command the majority of the National Assembly.64 Tom Thabane, the leader of the ABC was therefore accordingly appointed and sworn in as the Prime Minister on 8 June 2012.65

The 2015 election gave the country a second opportunity to test these constitutional conventions as the election produced yet another hung parliament. Lesotho held parliamentary elections on 28 February 2015. The Independent Electoral Commission took four days to announce the final seat allocation. When the final seats allocation was announced on Wednesday 4 March 2015, it became apparent that there was no single party with clear majority in the National Assembly. Political parties started political negotiations for a coalition government. On Wednesday 4 March 2015, seven political parties announced their provisional agreement to form a coalition,66 and to appoint the former Prime Minister, Pakalitha Mosisili, in terms of section 87(2) of the Constitution as the incoming Prime Minister. Of the ten political parties that managed to get seats in the National Assembly, only three parties - the ABC, BNP and Reformed Congress of Lesotho (RCL) - were not part of the coalition.

While the outcome on the vote for the Speaker may give a sense of how alliances stand, together with the publicly announced coalitions, the process is still uncertain and at most risky. Election of the Speaker may not necessarily be a show confidence by the sponsoring political party or parties in the government or Prime Minister. The Speaker may have his own popularity different from that of the Prime Minister.67

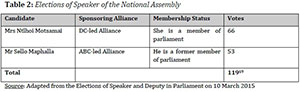

After the 2015 election, the total number of seats for all the seven coalescing political parties was 65 while the total number for the three parties68 in the minority coalition was 55. Ordinarily, it was expected that this is the structure of the vote for the elections of the Speaker. The Tables below show the structure of the votes for both the Speaker and the Deputy Speaker.

While it was already expected that the DC alliance as the majority coalition would win the vote, it would seem that the alliance got an additional vote. In terms of the coalition agreement the seven political parties have 65 votes. But as it appears from Table 1 above the coalition gained one more vote, and indeed the opposition coalition dropped one vote. This may mean that there is one member who just exercised his or her freedom as a member of parliament without any intention to defect. Another possibility could be that indeed the process of wooing members of parliament from one alliance to the other was not yet complete.

The election of the Deputy Speaker only confirms the results of the election of the Speaker. The DC-alliance seems to have gained one vote. It would seem that neither the express provisions of the Constitution nor constitutional practice can provide definite guidelines in Lesotho to the Council of State on how a government is formed in the case of a hung parliament. In that event, help could most appropriately be sought from British constitutional conventions on which the rule on the formation of a government is based. Even when the election has not been conclusive as to who clearly has the majority of the members, the fundamental principle that the government must be able to command the confidence of the National Assembly is still sacrosanct . The rationale for this principle is that in the absence of parliamentary confidence the resultant government lacks democratic legitimacy.70 Although Britain had its second hung parliament after the Second World War only in 2010,71 its ability to handle hung parliament situations is based on what are called "caretaker conventions".72 These conventions guide British constitutional practice from the dissolution of parliament until the formation of a new government.73 These conventions are generally accepted and applied in other Westminster designs, such as, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.74 One such convention, which is widely accepted, is that a caretaker government cannot resign. This is the convention by which parliamentary systems ensure that "the country is never left without a functioning executive".75 In Lesotho this convention is not so well-established. In 2012, Prime Minister Mosisili resigned before the first sitting of Parliament alleging that it is only a procedural formality.76 This left uncertainty in government. This was not only dangerous but also not in the interest of the country as he did not advise the King as to who should be invited to form a government when he resigned. The convention is even more important during a hung parliament than during clear majority situations because there is authority to the effect that the incumbent Prime Minister has a right to remain in office until his support is tested on the floor of the House.77 This is because the theory of Westminster parliamentary practice is that support or lack thereof for governments is determined "inside and not outside parliament".78 Another corollary to the convention is that the King may not dismiss a Prime Minister on the ground that he does not hold the confidence of parliament when parliament has not yet met to test it on the floor of the House. The Constitution of Lesotho has codified and slightly modified the convention. In terms of section 87(5)(b) of the Constitution, the King advised by the Council of State is entitled to dismiss a Prime Minster if after the general election, but even before the first meeting of the National Assembly, it appears that as a result of the election the sitting Prime Minister will no longer be able to command the confidence of the House.79It would seem that while the classic British convention gives the sitting Prime Minister an incumbency advantage of remaining in office until his confidence is tested on the floor of the house, the Constitution of Lesotho empowers the King to dismiss the Prime Minister even before the first meeting of the House. However it is critical to note that the section is couched in permissive language.80

In cases of a clear majority this section may be operationalised smoothly but in cases of a hung parliament the King must implement it with caution. Dismissal of a government is a highly partisan act which ordinarily conflicts with the convention that the King may not be seen to be partisan.81 While dismissal of a government is the longstanding prerogative of the King, it has latterly been hugely affected by the ascendancy of electoral democracy in terms which the power to dismiss government has largely shifted to the electorate or its representatives.82 In situations of a hung parliament the King is generally encouraged to exercise restraint. According to Brazier, during an inconclusive election "the guiding light should be political decisions politically arrived at".83 There is authority to the effect that where the political process fails to produce a way forward, the King's prerogative of dismissal and appointment of a Prime Minister may be necessary84. But the golden rule is not to draw the monarch into controversy or political negotiations.85 The best route, therefore, for the King is to leave the determination of who will command the majority in the House to the political negotiation process.

The Constitution of Lesotho does not have the timeline for the formation of a government after an election - only the time for the first meeting of Parliament is fixed.86 This process of negotiating the coalition may inordinately extend the caretaker period. However, it is important to note that, according to convention, caretaker periods are not healthy as government is expected to proceed with the policy status quo - the policy position that was in place when the outgoing government lost its parliamentary basis. This convention of limiting governments during caretaker periods is not widely and universally applied in all Westminster systems.87

Be that as it may, the principal question is whom and how should the King appoint under section 87 of the Constitution of Lesotho in situations of an inconclusive election. After the inconclusive election in 2010, Britain collated all its conventions relating to the formation and management of government into what is called the "Cabinet Manual".88 In situations of a hung parliament the Manual confirms the conventional view that where there is significant doubt following an election over the government's ability to command the confidence of the House of Commons, the nature of government formed will depend on "discussions between political parties and any resulting agreement".89

The Manual envisages fundamentally two ways in which a government may be formed out of the political bargaining resulting from an inconclusive election.90The first type which more closely resonates with section 87 of the Constitution of Lesotho, is through a formal coalition government. This is the arrangement by which parties agree to constitute a government comprising ministers from more than one political party, and they should conclusively command the majority of the House of Commons. This type was followed in Britain after an inconclusive election in 2010. The process resulted in the Conservative-Liberal coalition government.91 The process of negotiating coalitions becomes a generally open political process irrespective of the strength of political parties in terms of electoral outcomes. Similarly, this is the type that was followed in Lesotho after an inconclusive election in 2012. The only difference between Lesotho and Britain is that in Britain the party with the most votes in the House of Commons is the one which managed to put togeher and lead a coalition government. In Lesotho the person who was invited to form a government, Thomas Thabane, was from a party (ABC) which was the second strongest in the National Assembly.92 There does not seem to be any established convention to the effect that the party with the most seats in the House of Commons or National Assembly, as the case may be, has the first opportunity to form a government. What seems to be the corollary of confidence convention though, is that the King invites the person who will have the prospect of establishing a stable government.93

The second type of government that can result from the hung parliament is a single party, minority government. This is the arrangement where a party, normally the one with most seats in the House of Commons, is supported by other parties usually smaller parties through ad hoc agreements based on common interests.94 These agreements will assist government to survive a confidence testing parliamentary process in exchange for certain concessions to the other parties in respect of a political program. However, care must be taken when taking this route that government must at all material times enjoy the confidence of the House.

In 2012, the DC intimated its eagerness to try this avenue95 when the party realized that the provisional coalition of the ABC, LCD and BNP had taken the majority of the members of the National Assembly.96 However, the plan could not materialize. The constitutional challenge with this route that the DC wanted to take was that the other three political parties had already crunched a provisional agreement which prima facie managed to constitute the majority of the House. In that event, there is no way the DC would have been allowed to form a government when there was a majority in Parliament already. This second type works best when there is no other possible political agreement which is able to constitute the majority of the House.

In both types of negotiation, the process entirely depends on political dynamics. In 2010 in Britain the political negotiation was technically supported by the civil servants.97 In Lesotho the process was wholly private and political parties secured their own technical teams to negotiate and write up any coalition agreement. So, the process of negotiating a government out of a hung parliament is more of a political problem, than a constitutional one.98 As one British authority contends, a "hung parliament or even a succession of hung parliaments need not lead to a constitutional crisis".99

5 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It would seem that the fundamental principle that the government must at all material times enjoy the confidence of the National Assembly is applicable in Lesotho to both clear majority situations and situations of hung parliament. This convention is the bedrock of section 87 of the Constitution of Lesotho. Another important convention is that a government does not resign until someone who can command the majority of the National Assembly has been secured. It is the King's prerogative, which under the new Constitution of Lesotho is exercised with the advice of the Council of State, to appoint the Prime Minister. The Constitution states clearly that the electorate does not elect the Prime Minister. While this may be clearer under the circumstances of a clear majority, it may be tricky in the hung parliament situation. So it is prudent for the King not to be involved at early stage during political negotiations.

Be that as it may, it is apparent from the forgoing discussion that some reforms should be introduced to the process of formation of a government in Lesotho. Leaving it to broad British conventions creates a lot of uncertainty not only for the appointing authority, the monarch, but even the electorate. It always works best for the political system when the electorate knows with certainty the final outcome of the voting process. To that end, certain recommendations can be made regarding the development of the system. First, it may be important to clearly demarcate the caretaker period in Lesotho, and the restrictions placed on the government during this time. What is clear in terms of the constitution is that three months after dissolution of Parliament, there should be an election,100 and that 14 days after the announcement of the election results Parliament must convene.101As regards the timeline for the formation of a government and the restrictions on government during this time the Constitution is silent.

Secondly, proper codification of these conventions may be necessary. Lesotho has a written constitution so the first and supreme point of reference for the principles of government is the Constitution itself. So, reliance on unwritten constitutional conventions may lead to unnecessary conflict between political players. Thirdly, it is recommended that the Constitution should introduce an investiture vote for the Prime Minister. Leaving the determination of who shall become the Prime Minister to obscure political process creates unnecessary uncertainty that has potential to degenerate into conflict. An investiture vote is the process by which parliament after election sits to elect the Prime Minister.102 In this way Parliament is some sort of Electoral College to elect the Prime Minister on behalf of the electorate.103The vote should really be symbolic, just for purposes of certainty both for the electorate and the appointing authority. In the case of an inconclusive election, post-election coalition negotiations should precede the vote. Investiture vote will not only eliminate uncertainty in the process of formation of government but will also make the electorate indirectly elect the Prime Minister.

Other quasi-parliamentary systems, like Botswana and South Africa, have the investiture vote. In Botswana, the President is elected by the National Assembly; the President is not directly elected by the electorate.104 The Constitution of South Africa provides that at its first sitting after its election, 'and whenever necessary to fill a vacancy, the National Assembly must elect a woman or a man from amongst its members to be President'.105

1 See Boston J "Dynamics of government formation" in Miller R (ed) New Zealand government and politics, 5th ed (Melbourne: Oxford University Press 2010). [ Links ]

2 Matlosa K "The 2007 general election in Lesotho: managing the post-election conflict" (2008) 7(1) Journal of African Elections 20. [ Links ]

3 Constituency based electoral models, due to their inherent winner-takes-all feature, have a tendency to produce dominant party systems. See Currie I & De Waal J The new constitutional and administrative law (Cape Town: Juta 2001) at 133. [ Links ]

4 The trend of a dominant party system was only broken by the introduction of the mixed system in the 2002 general election.

5 See s 87(2) of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

6 See the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution Act No 4 of 2001.

7 The 2002 election is said to be remedial because it was following the disputed 1998 election. See Matlosa K "Conflict and conflict management: Lesotho's political crisis after the 1998 election" (1999) 5(1) Lesotho Social Science Review 163. [ Links ]

8 LCD got 79 constituency seats out of a 120 member House.

9 See the "Coalition Agreement between ABC, LCD and BNP" (2012).

10 Countries that use the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system invariably find themselves stuck with coalition politics. See Boston J "Government formation in New Zealand under MMP: theory and practice" (2011) 63 (1) Political Science 79. [ Links ]

11 Jennings I Cabinet Government (Cambridge; University Press 1969) 13.

12 For clarity on the virtues of the doctrine of representation see the decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa in Matatiele Municipality and Others v The President of the Republic of South Africa and Others 2006 (5) BCLR 622(CC).

13 To that extent, the Constitution of Lesotho can be said to be compliant with the continental and regional standards on democracy. See the African Charter on Democracy Elections and Governance adopted by the African Union on 30 January 2007.

14 Jennings (1969) 17.

15 See Phillips OH & P Jackson. Constitutional and administrative law 7th Ed (London: Sweet and Maxwell 1987). [ Links ]

16 See section 87(4) of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

17 S 87(7) of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

18 Grant M The UK Parliament (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2009) 6 the author says, [ Links ] quoting Bagehot, "cabinet is a combining committee - a hyphen which joins, a buckle which fastens the legislative part of the state to the executive part of the state. In its origin it belongs to the one and in its function it belongs to the other." However, Grant also observes that the de facto powers of parliament are limited by "majority government...".

19 On the general principles of constitutional monarchy, see Barker E British constitutional monarchy (London: COI (1958). [ Links ] See also Bogdanor V The monarchy and the constitution (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1955). [ Links ]

20 See s 86 of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

21 See s54 of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

22 See s120 of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

23 See Schapera I A handbook of Tswana law and custom (Frank Cass 1964). [ Links ]

24 In terms of s 87(1) of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993), this prerogative is subject to advice of the Council of State.

25 On the nature of constitutional conventions see Jaconnelli J "The nature of constitutional convention" (1999) 19(1) Legal Studies 24; [ Links ] Munro CR "Laws and conventions distinguished" (1975) 91 Law Quarterly Review 218. [ Links ]

26 Ghany HA "The evolution of the power of dissolution: the ambiguity of codifying Westminster conventions in the Commonwealth Caribbean" (1999) 5(1) The Journal of Legislative Studies 54. [ Links ]

27 1 9 6 3 AC 614. See also Adegbenro v Akintola & Another ("1963) 7(2) Journal of African Law 99.

28 The inherent nature of British constitutional conventions to the constitutional design was embedded by the proviso to section 76(2) of Lesotho's Independence Constitution of 1966 as follows: "Provided that, except in the cases specified in paragraphs (a), (f), (g), (h), (i) and (j) of this subsection (where he may have absolute discretion), King shall in the exercise of the said functions act, so far as may be, in accordance with constitutional conventions applicable to the exercise of similar functions by Her Majesty in the United Kingdom (emphasis added)."

29 Fombad CM "Constitutional reform and constitutionalism in Africa: reflections on some current challenges and future prospects" (2011) 59 Buffalo Law Review 1007. [ Links ]

30 It is interesting to note that the Constitution does not specifically provide for the functions of the Prime Minister.

31 See Barker (1958).

32 Phillips & Jackson (1987) 318.

33 See section 87(2) of the Constitution of Lesotho 1993.

34 See Palmer V & Poulter S The Legal System of Lesotho (Virginia:The Miechie Company 1972) at p 249.

35 Section 75 of the 1966 Constitution ((Schedule to Lesotho Independence Order No 1172 of 1966) provides that the King could "act in accordance with his own deliberate" in the performance of certain specified functions. Those were appointment of senators, dissolution of parliament, appointment of Prime Minister, dismissal of Prime Minister. The Constitution had the interesting proviso that "the King shall in the exercise of the said functions act, so far as may be, in accordance with any constitutional conventions to the exercise of a similar function by Her Majesty in the United Kingdom".

36 See for instance s 124 of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

37 See s 95 of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

38 For instance, the Judicial Service Commission. See s 132 of the Constitution of Lesotho.

39 Jennings (1969).

40 Bogdanor V "A hung parliament: a political problem, not a constitutional one" in Brazier A & Kalitowski S (eds) No overall control? The impact of a "hung parliament" on British politics (London: Hansard Society 2008) 19. [ Links ]

41 Under the independence constitution, the King used to have powers which he could exercise in accordance with his own deliberate judgement. These are the powers he could exercise without being advised by any authority under the constitution. They were in his absolute discretion subject only to the constitution. See s76(2) on independence constitution of 1966.

42 Bogdanor (2008) 20.

43 CIV/APN/75/97.

44 Sections 87(8) and 87(5) (a) of the Constitution of Lesotho (1993).

45 Ntsu Mkhehle v Molapo Qhobela & Others (1997) 17-18. Emphasis added.

46 Rasmussen J "Constitutional aspects of government formation in a hung parliament" (1997) Parliamentary Affairs 143. [ Links ]

47 Jennings (1969) 14.

48 See s 95 (1) of the 1993 Constitution.

49 Mahao NL "The constitution and the crisis monarchy in Lesotho" (1997) 10(1) Lesotho Law Journal 165 188. [ Links ]

50 Section 91(2) of the Constitution of Lesotho, 1993 provides: "Where the King is required by this Constitution to do any act in accordance with the advice of the Council of State and the Council of State is satisfied that the King has not done that act, the Council of State may inform the King that it is the intention of the Council of State to do that act after the expiration of a period to be specified by the Council of State, and if at the expiration of that period the King has not done that act, the Council of State may do that act themselves and shall, at the earliest opportunity thereafter, report the matter to Parliament; and any act so done by the Council of State shall be deemed to have been done by the King and to be his act".

51 Section 95(2) of the Constitution of Lesotho, 1993 provides for the composition of the Council of State thus: the Prime Minister; the Speaker of the National Assembly; two judges or former judges of the High Court or Court of Appeal who shall be appointed by the King on the advice of the Chief Justice; the Attorney-General; the Commander of the Defence Force; the Commissioner of Police; a Principal Chief who shall be nominated by the College of Chiefs; two members of the National Assembly appointed by the Speaker from among the members of the opposition party or parties; not more than three persons who shall be appointed by the King on the advice of the Prime Minister, by virtue of their special expertise, skill or experience; and a member of the legal profession in private practice who shall be nominated by the Law Society.

52 At independence, the King used to have deliberate powers whereby he could exercise pure discretion without any "advice". Section 75 of the 1966 Constitution (Schedule to Lesotho Independence Order No 1172 of 1966) states that the King could "act in accordance with his own deliberate judgement" in the performance of certain specified functions. Those were the appointment of senators, dissolution of Parliament, and appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister. The Constitution had the interesting proviso that ". the King shall in the exercise of the said functions act, so far as may be, in accordance with any constitutional conventions to the exercise of a similar function by Her Majesty in the United Kingdom".

53 Martin L & Stevenson R "Government formation in parliamentary democracies" (2001) 45(1) American Journal of Political Science 33. [ Links ]

54 Maer, L Hung Parliaments. House of Commons Library: Parliament and Constitution Centre, Standard Note: SN/PC/04951 (2010) 1.

55 Bogdanor (2008) 25.

56 Boston (2011) 80.

57 See 2012 election results available at www.iec.org.ls (accessed 30 December 2014).

58 See BBC, "Lesotho election: Tom Thabane's ABC to form coalition" 30 May 2012. Available at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa (accessed 20 January 2015).

59 Section 82(1)(b) of The Constitution provides: "...after Parliament has been dissolved, the time appointed for the meeting of the National Assembly shall not be later than fourteen days after the holding of a general election of members of the National Assembly and the time appointed for the meeting of the Senate shall be such time as may be convenient after nomination of one or more senators in accordance with section 55 of this Constitution".

60 See s 63(4) of the Constitution.

61 Lesotho News Agency (LENA) "Honourable Motanyane new Speaker of National Assembly" 6 June 2012 available at http://www.gov.ls/articles/2012/hon_motanyane_new_speaker.php (accessed on 20 January

2015).

62 The total number of seats for the three parties was 61 seats out the 120. Mr. Motanyane got 71 votes, beating another candidate for the position, Ms. Ntlhoi Motsamai, who got 49.

63 After the 26 May 2012 National Assembly Election, the ABC, LCD and BNP came together to form a government with 61 seats. The DC and Basotho Batho Democratic Party (BBDP) also came together to form the official opposition with 49 seats, while six parties - the Lesotho People's Congress (LPC), Lesotho Workers' Party (LWP), Marematlou Freedom Party (MFP), National Independent Party (NIP), Basotho Democratic National Party (BDNP) and Popular Front for Democracy (PFD) officially identified themselves as the "Bloc" with 10 seats.

64 The election of the Speaker became the apparent confirmation of how alliances stand in the National Assembly, and who would be able to command the majority of the House.

65 It is important to note that there was never any voting by the National Assembly. There is no voting that is necessary for the choice of the Prime Minister in Lesotho.

66 The seven political parties that announced a provisional coalition were the Democratic Congress (DC), Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD), Popular Front for Democracy, National Independence Party (NIP), Marematlou Freedom Party (MFP), Lesotho People's Congress (LPC) and Basotho Congress Party (BCP).

67 In the 2012 election for the Speaker of the National Assembly, the votes far outnumbered the seats of the provisional coalition of ABC, LCD and BNP.

68 The ABC, BNP and RCL.

69 The number is 119 as opposed to 120 because one member of the RCL, Dr Motloheloa Phooko was not in attendance. He finally relinquished his position in Parliament. It is still unknown, however, who from the opposition benches consistently voted with the government alliance in both the Speaker and Deputy Speaker elections.

70 Schleiter P & Belu V "The Challenge of Periods of Caretaker Government in the UK" (2014) Parliamentary Affairs 1. [ Links ]

71 Maer (2010).

72 Schleiter & Belu (2014).

73 Schleiter & Belu (2014).

74 See Boston J "Dynamics of government formation" in R, Miller (ed) New Zealand government and politics, 5th ed (Melbourne: Oxford University Press 2010). [ Links ]

75 Boston (2010) 455.

76 SABC News "Lesotho Prime Minister Mosisili resigns after poll loss" Wednesday 30 May 2012 available at http://www.sabc.co.za/news/ (accessed 15 March 2015).

77 Twomey A "The Governor-General's role in the formation of government in a hung parliament" Sydney Law School Research Paper No 10/85 (August 2010).

78 Twomey (2010) 3. See also Harris MC & Crawford J "The powers and authorities vested in him - the discretionary authority of state governors and the power of dissolution" (1969) 3(3) Adelaide Law Review 303. [ Links ]

79 Section 87(5) Provides:

"The King may, acting in accordance with the advice of the Council of State, remove the Prime Minister from office-

(a) if a resolution of no confidence in the Government of Lesotho is passed by the National Assembly and the Prime Minister does not within three days thereafter, either resign from his office or advise a dissolution of Parliament; or

(b) if at any time between the holding of a general election to the National Assembly and the date on which the Assembly first meets thereafter, the King considers that, in consequence of changes in the membership of the Assembly resulting from that election, the Prime Minister will no longer be the leader of the political party or coalition of political parties that will command the support of a majority of the members of the Assembly".

80 It is important to note that the section uses the word "may", not "shall". It therefore theoretically leaves some discretion to the King to make a determination. It is, however, ordinarily expected that the King may retain the Prime Minister who has lost the support of the majority of the members of the National Assembly.

81 Brazier R "Monarchy and the personal prerogatives - a personal response to Professor Blackburn" (2005) Public Law 45. [ Links ]

82 Rusmussen, J "Constitutional aspects of government formation in a hung parliament" (1987) 40(2) Parliamentary Affairs 139. [ Links ]

83 Brazier R Constitutional practice; the foundations of British government, 3rd (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1999) 37. [ Links ]

84 Hazell R & A Paun A Making minority government work; hung parliaments and the challenges for Westminster and Whitehall (London: Institute for Government 2009). [ Links ]

85 Hazell & Paun (2009).

86 See s 82(1((b) of the Constitution of Lesotho 1993.

87 Schleiter & Belu (2014).

88 United Kingdom Cabinet The Cabinet Manual; a guide to laws, conventions and rules on the operation of government (2011).

89 The Cabinet Manual (2011) 14.

90 The Cabinet Manual (2011) 14.

91 See the Conservative-Liberal Coalition Agreement styled "The Coalition: our programme for government" (2010) available at www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/news/coalition-documents (accessed 25 April 2015).

92 See Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) "Lesotho National Assembly Elections 26th May 2012" The party with most votes (40 per cent) was the DC.

93 Generally see Blackburn R "Monarchy and the Personal Prerogatives" (2004) Public Law 546; [ Links ] See also Brazier (2005).

94 See The Cabinet Manual (2011) 14-15.

95 'What is a constitutional minority government?" Sunday Express 2 June 2012.

96 The three parties had 61 of the 120 members of parliament.

97 Maer (2010).

98 Bogdanor "2008).

99 Bogdanor "2008).

100 Section 84(1) of the Constitution of Lesotho 1993.

101 Section 82 (1) (b) of the Constitution of Lesotho 1993.

102 Bergman T "Constitutional design and government formation: the expected consequences of negative parliamentarism" (1993) 16(4) Scandinavian Political Studies 282. [ Links ]

103 There is a view held by some members of the public to the effect that the Prime Minister must be elected directly by the electorate. See Development for Peace Education. Report on Community Voices on New Zealand Report (2014). The argument that the electorate must move closer to the election of Prime Minister has merit. However, the direct election of the Prime Minister will affect the fabric of the design as a parliamentary model. There are advantages in allowing the parliamentary nature of the system to evolve and develop incrementally. Even semi-parliamentary systems like South Africa and Botswana still retain the parliament as the epicenter of the political system.

104 See section 32 of the Constitution of Botswana 1966. For an analysis of the constitutional and political design in Botswana see Good K "Authoritarian liberalism: a defining characteristic of Botswana" (1996) 14(1) Journal of Contemporary African Studies 29. [ Links ]

105 See s 86 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996.