Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.19 Cape Town 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/LDD.V19I1.9

The Investor-State Dispute Resolution Forum under the SADC Protocol on Finance and Investment: Challenges and opportunities for effective harmonisation

Lawrence NgobeniI, *; Babatunde FagbayiboII

IDoctoral candidate, College of Law, University of South Africa

IISenior Lecturer, Department of Public, Constitutional and International Law, College of Law, University of South Africa

1 INTRODUCTION

Regional integration measures are largely seen as a vehicle for development. The African regional integration project has been in existence for decades, with the African Union (AU) seen as the primary driver of continental integration. Together with seven other sub-regional institutions,1 the Southern African Development Community (SADC) is regarded as a "building block" of regional integration in Africa. The expectation is that these eight regional economic communities (RECs) will eventually harmonise all their structures and policies under the banner of the AU, and then achieve continental integration in Africa. 2

It is in this context that the SADC has put in place a number of policies and structures aimed at deepening integration in the region. An example of this is the SADC Protocol on Finance and Investment (FIP), which requires Member States to harmonise their investment policies, laws and practices with the objective of creating a SADC investment zone.3 The FIP was signed on 18 August 2006, and came into effect on 16 April 2010.4 An issue which arises is the level of progress that has been made by SADC Member States towards the harmonisation of their policies, laws, and practices, especially as they relate to the resolution of investor-State disputes in accordance with the FIP.5 At present, there are major differences between the investment policies, laws and practices of SADC Member States. A case in point is the Investor-State Dispute Resolution Forum. In this regard, the FIP provides that investors must be given access to local courts, as well as access to international arbitration after the exhaustion of local remedies.6 Furthermore, in 2012, the SADC introduced the Model Bilateral Investment Treaty Template (Model BIT) with a view to further foster the harmonisation of investment laws and practice at BIT level. However, the FIP and the Model BIT differ significantly with regards inter alia to their provisions for the resolution of investor-state disputes, with major implications for harmonisation.7 Probably due to this and other reasons, the FIP is in the process of being amended.8 Currently, while a few States are compliant with the FIP, in terms of investor-State dispute resolution, the investment policies and laws of other Member States remain in conflict with the FIP.9 Furthermore, South Africa is moving away from international arbitration.10 Some States such as Lesotho, are working on new investment policies, and others, such as Namibia, are revising existing policies. Mauritius and South Africa have completed their policy reviews.

The thrust of this article is consideration of the feasibility of the effective harmonisation of investment laws and policies in the SADC region, particularly within the context of the Investor-State Dispute Resolution Forum. In other words, is the creation of a SADC investment zone possible considering the factors on the ground? In order to address this, the article looks at some of the amendments that should be made to the FIP, the extent of alignment between the FIP, the Model BIT and national investment codes, and the level of political will necessary for such harmonisation.

The article begins with an overview of the FIP and Model BIT frameworks. It then provides an outline of the current State practice in the SADC in terms of the Investor-State Dispute Resolution Forum. It concludes by looking at some of the politico-legal measures that should be adopted in order to ensure the effective harmonisation of investment laws and policies in the SADC.

2 THE FIP AND THE MODEL BIT: AN OVERVIEW

2.1 The FIP

The FIP is a subsidiary instrument formed under the auspices of the SADC Treaty.11 The objective of the FIP is to "foster harmonisation of the financial and investment policies of the State Parties in order to make them consistent with objectives of SADC and ensure that any changes to financial and investment policies in one State Party do not necessitate undesirable adjustments in other State Parties". 12

One of the ways in which the FIP seeks to achieve this objective is by creating a favourable investment environment within the SADC, with the aim of attracting and promoting investment.13 The FIP thus fosters the creation of a SADC investment zone with a common Regional Investment Policy Framework.14 Towards this end, Article 19 of Annex 1 of the FIP anticipates that Member States' investment policies, laws and practices shall converge into a single investment regime applicable across the anticipated SADC investment zone.15 This implies that the presently divergent state policies, laws and practices must gradually change so as to converge into a single regional regime agreed to by Member States.16 The Baseline Summary describes the harmonisation process as follows:

Focus shifts from individual Member States to the region. Agreement is reached on harmonised standards, systems and policies. Through domestic adoption of these, individual domestic frameworks start to look and function the same. At the end of this phase, all domestic frameworks are harmonised to a regional standard. 17

Articles 27 and 28 of Annex 1 of the FIP are central to this article, as they deal with the resolution of investor-State disputes in the SADC. Article 27 of Annex 1 provides that States must provide investors with a right of access to the courts for the resolution of investment-related grievances.18 Article 28 of Annex 1 provides that in the event of an investor-State dispute not being resolved amicably, and after the exhaustion of local remedies, the dispute shall be resolved by arbitration under either of International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) or the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) if one of the parties so elects.19 In this regard, it appears from reports that UNCITRAL arbitration has been brought against Lesotho by Swissbourgh Diamond Mines (Pty) Ltd, in a matter which has unsuccessfully spanned the courts of Lesotho, South Africa and the SADC Tribunal since 1991.20

2.2 The Model BIT

Article 28 of the Model BIT provides for the resolution of disputes between States, relating to the Model BIT. More specifically, it provides that a State may bring ICSID or UNCITRAL arbitration proceedings against a host State on behalf of its national who suffered loss as a result of the actions of the host State.21 Article 29 of the Model BIT is the provision that deals with the resolution of investor-State disputes. It provides the pre-conditions for arbitration,22 as well as details of the arbitration forum and arbitration rules.23 Although both the FIP and the Model BIT deal with the resolution of investor-State disputes, they differ in some fundamental respects, as shown below.

First, in terms of Article 28 of the Model BIT, a SADC State can bring arbitration proceedings against another SADC state on behalf of an investor who is its national, while the FIP does not provide for this.24

Secondly, unlike the FIP, the Model BIT does not make investor-state international arbitration a mandatory provision in a BIT.25 It acknowledges that some states, such as South Africa, may not wish to utilise international arbitration. This point is further buttressed by State practice in the region. As investment codes show, the majority of SADC States do not prefer international arbitration, since only a third of SADC states provide for international arbitration.26

Thirdly, unlike the FIP, Article 29(6) of the Model BIT provides for regional and other arbitration forums in addition to ICSID and UNCITRAL arbitration. The provision for additional forums is commendable, given that not all SADC States are Members of the ICSID Convention, which in turn makes ICSID arbitration unavailable to investors from non-ICSID Member States.27

Fourthly, unlike the FIP, Article 29(4)(d) of the Model BIT introduces the defence of prescription of claims after a period of three years from

[T]he date on which the Investor first acquired, or should have first acquired, knowledge of the breach alleged in the Notice of Arbitration and knowledge that the Investor has incurred loss or damage, or one year from the conclusion of the request for local remedies initiated in the domestic courts.

Prescription is a welcome provision, because it ensures that disputes between parties do not remain hanging perpetually.28

Fifthly, unlike the FIP, Article 29(4)(b)(1)(i) of the Model BIT introduces the requirement than an investor must first exhaust administrative remedies, followed by local remedies in the host State. Furthermore, where local remedies are commenced, an investor may only commence arbitration proceedings where "...a resolution has not been reached within a reasonable period of time from its submission to a local court of the Host State." It is submitted that this provision is potentially problematic, mainly because there is nothing in the Model BIT to indicate a reasonable period for the conclusion of litigation. The delay in the conclusion of litigation in some SADC Member States remains a worrying concern. For example, according to the American Department of State Investment Climate Statement, it takes about four years for an investment matter to be finalised in Angolan courts.29 The Statement reports in this regard

The Angolan justice system is slow, arduous, and not always impartial. Legal fees are high, and most businesses avoid taking commercial disputes to court. The World Bank's Doing Business in 2014 survey ranks Angola at 187 out of 189 on contract enforcement, and estimates that commercial contract enforcement, measured by time elapsed between filing a complaint and receiving restitution, takes an average of 1,296 days, at an average cost of 44.4 per cent of the claim.30

On Zambia, the Statement observes: "The Zambian judicial system has a mixed record in upholding the sanctity of contracts. The judicial process is lengthy and inefficient. Many magistrates lack experience in commercial matters." 31 The Statement expresses a similar view regarding Mozambique

Recourse to the judicial system in Mozambique can present many obstacles for potential investors. Generally, the Mozambican judicial system is largely ineffective in resolving commercial disputes and certain cases consume a large amount of time and resources. Instead, most disputes among Mozambican parties are either settled privately or not at all, and there are no discernible patterns to resolution of investment disputes. 32

These points highlight the imperativeness of stipulating a timeframe for the conclusion of local proceedings, which is more objective and can easily be determined from the language of a provision.33 In addition, they highlight the challenges of corruption, delays in finalising cases, high litigation costs, inefficiency and lack of political independence. It is submitted that these challenges will need to be addressed in order to secure investor confidence, especially in the event that international arbitration is removed from the FIP, because local courts will then be the only forum for the resolution of investor-State disputes.34

Sixthly, unlike the FIP, Article 29(4)(c) of the Model BIT introduces a "fork-in-the road" provision. This implies that once an investor chooses a forum to resolve a dispute, he or she may not, thereafter, approach another forum for the resolution of the same dispute.35

Seventhly, unlike the FIP, Articles 28(12) and 29(17)(b) of the Model BIT provide that arbitration hearings are to be open to the public, and may be broadcast live via the internet.36

Eighthly, Articles 28(10) and 29(17)(a) of the Model BIT provide that a State Party to an investor-state dispute shall upon receipt of a notice of intention to arbitrate, the notice of arbitration and subsequent pleadings, make these publicly available. Again this is commendable, as it increases public access to proceedings and in turn, enhances transparency.

Finally, Article 29(3) of the Model BIT provides that a State may, upon receipt of a notice from an investor that it wishes to commence arbitration proceedings, propose mediation.

3 AN OUTLINE OF INVESTOR-STATE DISPUTE RESOLUTION FORUMS IN SADC MEMBER STATES

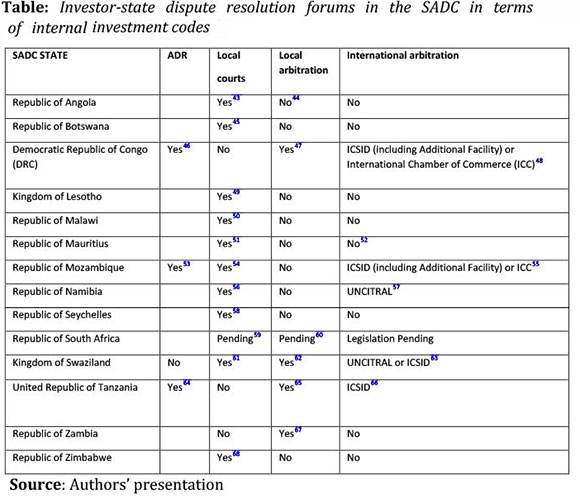

In the international arena, States are required to settle disputes by peaceful means.37Within the SADC region, States are also required to resolve disputes by peaceful means.38 As shown above, the FIP and the Model BIT provide for the settlement of investor-State disputes through alternative dispute resolution methods,39 arbitration40and the courts of a host State.41 The Table below provides a summary of the forums for investor-State dispute resolution in SADC States. It is based on the investment laws and constitutions applicable to general economic sectors in the various states.42

The following observations can be deduced from the tabulated summary above.

(a) Only a few States provide for preventative alternative dispute resolution in their investment codes.

(b) Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe provide for the resolution of investor-State disputes before local courts.69 Of these states, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Zimbabwe do not provide for any other forum as an option.

(c) Only the DRC, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, and Swaziland provide for international arbitration in their investment codes. Of these five States, the DRC, Namibia, and Swaziland provide consent to international arbitration in advance. Although Mozambique and Tanzania provide for international arbitration, the granting of consent to arbitration is delayed until a dispute arises, and the consent, if finally given, must be mutual.70 All the five States which provide for international arbitration provide for ICSID arbitration. Only the DRC and Mozambique provide for ICSID arbitration under the Additional Facility Rules.71 Only Namibia and Swaziland provide for UNCITRAL arbitration. Only the DRC and Mozambique provide for ICC arbitration.

(d) Angola, the DRC, Swaziland, Tanzania, and Zambia provide for local arbitration.72 Of these States, Zambia provides local arbitration to the exclusion of local courts and international arbitration.73 Angola and Zambia provide for local arbitration to the exclusion of international arbitration, while the DRC, Tanzania, and Swaziland provide for local arbitration as well as the option of international arbitration.

It is clear from the above that State practice, as seen in investment codes, is far from compliant with the FIP, especially with regard to international arbitration. This thus raises the following questions, which States are better placed to answer for themselves: Why do so few States provide for international arbitration in their codes, while they provide for it in their BITS?74 Are the States providing for international arbitration because they favour foreign investors over local investors?75 Is it a burden for States to provide for international arbitration? If so, what are the underlining factors? If international arbitration is burdensome, will States rid themselves of compliance with this requirement by removing mandatory international arbitration from the FIP? Or will they retain it for the benefit of all investors in the SADC? This is a policy decision to be taken by both States and the SADC. Suffice it to note that effective harmonisation can play an important role in eliminating these inconsistencies, and thus provide a more conducive environment for trade and investment. The feasibility of effective harmonisation is addressed below.

4 CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS OF EFFECTIVE HARMONISATION OF INVESTMENT LAWS, POLICIES AND PRACTICES IN THE SADC

There are a number of challenges affecting the feasibility of effective harmonisation of investment laws and policies in the SADC.76The first challenge is whether the FIP must provide for international arbitration or not.77 Secondly, there are possible challenges caused by the fact that some SADC States are also members of other regional economic bodies. This may cause a conflict if the measures which are to be embodied in the FIP conflict with those of another regional body.78 Thirdly, there the possibility of competition for investments among states, a situation that may make agreement on a single SADC-wide investment regime impossible.79 As the Baseline Regional Report notes

In fact, evidence from interviews suggests that investment competition among member states remains high, and so there has been difficulty in gaining consensus on a regional investment policy framework. Member states will be reluctant to harmonise where this impacts their ability to compete and where it is not in the national interest to do so.80

Fourthly, the fact that the FIP does not have timelines for its implementation could also hinder its effective realisation.81 And finally, a critical issue is the lack of political will on the part of Member States to bring about an effective articulation and implementation of harmonisation of standards and rules. Against this background, this section considers both the normative and political measures that are imperative for ensuring the effective harmonisation of investor-state dispute resolution in the SADC.

4.1 Normative measures

In view of aligning the provisions of the FIP, the Model BIT and States' investment codes, it is important to consider the following proposed measures.

The first proposed measure is that the alternative dispute resolution provisions of Article 29(4)(a) of the Model BIT be incorporated into the FIP.82 Based on the decisions in Stati & others v Republic of Kazakhstan,83 Kilic v Tukmenistan,84 and Tulip Real Estate v Republic of Turkey,85should it be necessary to retain in the FIP a cooling-off period or other pre-condition to arbitration, such provision should be carefully worded in clear and unequivocal language.

Secondly, the exhaustion of local remedies provisions of Article 29(4)(b) of the Model BIT in this regard should be incorporated into the FIP. In this respect, it is important to include a timeframe for an investor to await a verdict from a court after commencement of litigation.86 The exhaustion of local remedies is an established rule of international law, and such provision is, therefore, not controversial.87

Thirdly, the transparency provisions in Articles 28(12) and 29(17) of the Model BIT should be incorporated in the FIP. 88 This point speaks to the standard of fairness and openness of adjudicative proceedings, and is in accordance with international standards.89

Fourthly, if States wish to manage treaty shopping,90 Article 26 of the Model BIT should be incorporated into the FIP.91 The use of shell companies can be avoided by phrasing the definition of "an investor" to exclude investors who do not have substantive or substantial activities in their home State.92 If the FIP, BITs and investment codes have the same investor-state dispute resolution and substantive provisions (such as, "Most Favoured Nation" and "Fair and Equitable Treatment" clauses), the incentive for treaty shopping should be reduced.93

Fifthly, Article 27 of the FIP should be retained as it provides an investor with a fair right of access to the courts of a host State.94 The Article complies with Article 4(c) of the SADC Treaty, which requires Member States to conform to the principles of human rights, democracy and the rule of law.95 The concept of the rule of law entails access to the courts and the right to be heard.96 In turn, the right to be heard encompasses the right to a fair hearing before a person is deprived of an interest, right or legitimate expectation.97 Therefore, a decision or even a law which violates this rule is ultra vires and amounts to a denial of justice.98 Denial of justice may violate the fair and equitable treatment standard, thereby exposing a State to claims for breach thereof.99

With regard to the "prior notice" requirement, it must be noted that recent decisions have ruled that the provisions must be invoked before a dispute arises between the parties: prior notice must have been given before the dispute arose that the investor will be denied benefits. This provision is also contained in Article 17 of the USA Model BIT, Article 18 of the Canada Model BIT, Article 17 of the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) and Article 1113 of the NAFTA (which are similar to Article 26 of the Model BIT). For recent cases on this issue see Anatolie Stati v Republic of Kazakhstan SCC Arbitration (case 116/2010) Award of 19 December 2013 at 162 para 745; and Liman Caspian Oil BV v Republic of Kazakhstan (ICSID Case No. 07/14) Award of 22 June 2010 at 60 paras 224 -225. Both cases dealt with Article 17 of the ECT.

Sixthly, it is suggested that the provisions of Article 29(4)(d) of the Model BIT regarding prescription of claims be incorporated into the FIP.

Seventhly, the inclusion of Article 28(3)(a) of the Model BIT in the FIP should be considered.100 This novel provision enables a home state to intervene on behalf of an investor against a host State, and will benefit investors who may not have the financial resources to arbitrate against a host state.

Eighthly, it is suggested that the SADC should take a policy stance as to whether the FIP must provide for arbitration or not. If it is decided that the FIP must provide for arbitration, then the next consideration is whether to provide for international and/or local arbitration or not. The next consideration is whether States must provide consent to arbitration in advance,101 or make the decision to grant or refuse consent when a dispute arises.102 The former approach, where a State consents to arbitration in advance, suits an investor, because it gives an investor a guarantee that arbitration will take place if the investor wants it. On the other hand, it does not suit a State which does not want arbitration, or is unsure which arbitration policy to adopt, or which may in the near future not want it.

The second approach is suitable for States that prefer the flexibility of using arbitration when they so wish, without being bound to do so all the time. Due to its noncommittal nature, this approach may suit States which do not prefer arbitration (especially international arbitration), because it gives a State the flexibility to decide when to arbitrate and when not to. The approach also suits States which are undecided on the issue, since they do not have to make a final commitment to international arbitration immediately, but rather they can decide on a case by case basis. This proposal allows States to provide for arbitration, without committing to making it happen in the future. This flexible approach may be best suited in the SADC context, assuming that not all States are in favour of international arbitration, or that some States may be unsure what position to adopt towards international arbitration.103

In the event that a decision to provide for international arbitration is made, it is recommended that provision be made for the use of the ICSID Additional Facility, as this will enable investors from non-ICSID States, such as South Africa, to access ICSID arbitration if the host State is an ICSID Member State.104 This will also reduce the prospect of treaty shopping. On this point, it is also recommended that UNCITRAL arbitration be retained as an option to ICSID arbitration, as is currently the position.105

Finally, in the event that international arbitration is removed from the FIP by the deletion of article 28, then the local courts of member should ideally be placed in such a position that those investors who cannot access international arbitration via BITS or investment agreements will have confidence in them. This may entail inter alia addressing the challenges raised by the American Department of State as indicated above.

4.2 Political measures

The socio-political context of the promotion of investment in the SADC is an important factor. Beyond the normative issues, the success or otherwise of the FIP will largely depend on the willingness of Member States to provide the right political environment for its operations. Some of these measures are discussed below.

Firstly, there is the need to commit to principles of good governance and democracy. Although six SADC Member States feature in the top ten best governed countries in Africa according to the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG),106 a number of concerns about the levels of democratic governance in the region still remain. As indicated above, there are issues regarding judicial independence and transparency in some Member States, such as, Angola, Mozambique and Zambia.

According to the Freedom House Report (2014), four SADC Member States are regarded as "not free"107 and six are regarded as "partly free".108 Political instability, fraudulent elections, conflicts, and violation of human rights are some of the key problems. These issues are capable of undercutting the impact of the FIP in promoting trade and investment in the region. In this regard, it is imperative that the SADC promote adherence to democratic values and principles in the region. As Mapuva and Muyengwa-Mapuva rightly point out, democracy is important for the attainment of integration, and that lack of democracy negatively affects integration efforts.109 This will require serious commitment to the SADC and AU guidelines and normative standards on democratic governance, and the sanctioning of errant Member States.

Secondly, there is the need to establish a dedicated SADC or State level "investment ombud" or other office dedicated to facilitate the effective implementation of the resolution of investment dispute issues.110 Such unit should be tasked with ensuring compliance with the standards set out in national investment codes or the amended FIP, and to also report on the progress of implementation and challenges thereto. It could, for example, be composed of civil society representatives, retired judges, academics, and lawyers, with the mandate of resolving disputes (with or without an appeal or review mechanism) as well as of advising States or the SADC on how best to enhance the standards of investor-state dispute resolution measures. The establishment of this office will go a long way to not only adding substance to the goal of an effective harmonisation framework, but also enhancing the SADC institutional processes.

Thirdly, there is the need for stronger synergy among the critical stakeholders -the SADC, Member States and civil society. Such collaboration should be aimed at creating awareness on the imperative of the FIP, and also encouraging adherence to the salient provisions on investor-State dispute resolution in Member States. This will require engagement with the business community, especially by the incorporation of these standards into legal and business training and practice. In addition, there is the important need to work closely with the legal fraternity in the SADC Member States on issues relating to awareness of, and alignment of national legal practice with, FIP measures.

Lastly, SADC institutions must be properly aligned to deliver on integration. A critical point in this respect is that the SADC Summit, which is composed of heads of state and government, has too much power over all other institutions.111 Writing in the context of the beleaguered SADC Tribunal, Saurombe observes

Evidence from the dissolution of the SADC Tribunal clearly shows that SADC institutions are not independent of the influence of Member States. Furthermore, key institutions within the organisation should work in harmony and exercise their powers in a manner that reflects the common agenda of the regional body. The SADC Summit is clearly playing a bullying role on the institutions which report to it.112

Such concentration of powers in one body is clearly antithetical to the development of regional integration processes. It is, therefore, essential that the SADC Summit find ways of devolving powers to other organs of the organisation. In the context of the FIP, the body should endow the SADC Secretariat with the requisite competences to formulate and implement guidelines for the attainment of the FIP. This includes the establishment of the "ombud" suggested above.

5 CONCLUSION

Until such time that States adjust their investment laws, policies and practices to be in accordance with the FIP or other SADC level instrument or policy, different and varying regimes for the resolution of investment disputes will remain. The first will be regulated by the Member States' investment codes. The second will be regulated by BITs entered into by the States. The third will be in terms of investor-State agreements. The fourth will be regulated by the FIP at SADC level. These arrays of option available to an investor do not bode well for harmonisation, because they defeat the objective of having a single, SADC wide investment regime. First, this may lead to treaty shopping.113Second, local investors may be worse off with respect to the Investor-State Dispute Resolution Forum, especially in situations where investment codes provide for dispute resolution in local courts only, while BITs provide for international arbitration and also provide more rights for investors. This in turn may also lead to local investors using treaty shopping as a means of suitably positioning themselves. Considering that States need both local and foreign investments, the rationale for discriminating against local investors is hardly justifiable.

This article has considered some of the underlying issues on the feasibility of effective harmonisation of investment laws and policies in the SADC. The different approaches of Member States to investor-state dispute resolution remain a major concern, which can be better addressed through some normative and political interventions. The article suggested a number of amendments to the FIP and the need for Member States to demonstrate the requisite political will for creating a favourable climate for the resolution of investor-state disputes. As raised by the American Department of State, some local courts of the SADC Member States face various challenges which may affect their efficiency and attractiveness to investors. Such challenges should be addressed to win investor confidence.

Overall and in conclusion, the road to the creation of a single investment regime for the SADC will not be an easy one. States have and can meet the challenges discussed above, only if they invest the right amount of political will and commitment.

* A version of this article was first presented at the BRICS Regional Integration Workshop, organised by the College of Law, University of South Africa, from 9 - 10 September 2014, at Zambezi, Pretoria. This article is also based on a doctoral study being undertaken by Lawrence Ngobeni.

1 These are: The Community of Sahel-Sahara States (CEN-CAD); The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA); East African Community (EAC); Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS); Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS); Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD); Arab Maghreb Union (UMA). For more information see, for example, http://www.uneca.org/oria/pages/african-union-au-regional-economic-communities-recs-africa and http://www.au.int/en/, and select the "REC's" link (accessed 26 August 2014).

2 See Article 3(l) of the African Union Constitutive Act.

3 Art 19 Annex 1 FIP. The FIP is available at http://www.sadc.int/documents-publications/show/1009 (accessed 10 August 2014).

4 See http://www.sadc.int/documents-publications/show/1009 (accessed 10 August 2014). The delay in the coming into effect of the FIP was due to the slow pace of the ratification by Member States. Article 29 of the FIP requires ratification by two-thirds of all Member States.

5 The investor-state dispute resolution measures which are the focus of this article relate to the preconditions to be met prior to commencement of arbitration or litigation, as well as the forum for the resolution of the dispute. These are dealt with under Article 27 and 28 of the FIP, and Articles 28 and 29 of the SADC Model Bilateral Investment Treaty Template. Available at http://www.iisd.org/itn/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/sadc-model-bit-template-final.pdf (accessed 10 August 2014).

6 Art 27 and 28 Annex 1 FIP.

7 The differences are outlined in Section 2.2 below.

8 We requested details of the amendments from the SADC but were advised that the details are confidential at this stage. Therefore, we can only speculate on what aspects of investor-state dispute resolution may be amended.

9 See the discussion in Section 3 below.

10 See for example "Bilateral investment treaty policy review: Government Position Paper." Available at http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/docs/090626trade-bi-lateralpolicy.pdf (accessed 4 September 2014). As a result of this policy, the Promotion and Protection of Investment Bill, of 1 November 2013, does not provide for international arbitration of investoe-State disputes. For a recent version of the Bill see http://www.thedti.gov.za/business_regulation/bills/Investment2015.pdf (accessed 22 December 2015).

11 The FIP was formed in terms of Articles 21 and 22 of the SADC Treaty. For a copy of the SADC Treaty see http://www.sadc.int/documents-publications/sadc-treaty/ (accessed 12 August 2014).

12 Art 2(1) Annex 1 FIP. Emphasis added.

13 Art 2(2)(a) Annex 1 FIP. The other ways of achieving this objective are listed in Articles 2(2)(c)-(n) of the FIP. Annex 1 of the FIP deals with the harmonisation of the investment regime in SADC, and is the focus of this article.

14 See the report "Striving for Regional Integration: Baseline Study on the Implementation of the SADC Protocol on Finance and Investment" (Baseline Summary) at 4. Available at http://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2012-en-implementation-sadc-finance-investment.pdf (accessed 2 September 2014). This report is a summary of the main study, "Protocol on Finance and Investment Baseline Study: Regional Report August 2011" ("Baseline Regional Report"). Available at http://www.finmark.org.za/wp-content/uploads/pubs/SADC-FIP-Baseline-Study-Regional-Summary-Report-Final-5-August-20113.pdf (accessed 2 September 2014).

15 See also Baseline Summary at 4, Table 1, in the section where Article 19 is referred to.

16 The Baseline Summary states that the Regional Investment Policy Framework will be drafted by Member States (at 4 Table 1). This is also supported by the first objective of the FIP, which in terms of Article 2(1) is to "... foster harmonisation of the financial and investment policies of the State Parties in order to make them consistent with objectives of SADC..."

17 Baseline Summary at 3.

18 Art 27 Annex 1 FIP. This Article uses the term "grievance", not "dispute".

19 Art 28 Annex 1 FIP.

20 See http://www.italaw.com/cases/2256 (accessed 20 September 2014). Details of this matter are not available, partly because this being an UNCITRAL ad hoc arbitration, there is often a veil of secrecy around the proceedings, in addition to it not being known where the proceedings are opened. The amount being claimed in the last proceedings before the SADC Tribunal was R1.3 billion (SADC Tribunal Case No SADC (T) 04/2009). The proceedings were aborted due to the suspension of the SADC Tribunal. See Rupel C "SADC environmental law and the promotion of sustainable development" (2012) 2 SADC Law Journal at 268. [ Links ] For the last judgment issued by the South African Supreme Court of Appeal, and which gives a detailed presentation of the history of the case see http://www.justice.gov.za/sca/judgments%5Csca_2007/sca07-109.pdf (accessed 20 September 2014). The case is reported as Van Zyl and others v Government of Republic of South Africa and Others [2007] SCA 109 (RSA).

21 Arts 28(3)(a), 28(5) and 28(9) Model BIT.

22 Art 29(4) Model BIT.

23 Arts 29(5) - 29(20) Model BIT.

24 Art 28(3)(a) Model BIT.

25 See Special Note to Article 29 which states "The Drafting Committee was of the view that the preferred option is not to include investor-State dispute settlement. Several States are opting out or looking at opting out of investor-State mechanisms, including Australia, South Africa and others. However, if a State does decide to negotiate and include this, the text below provides comprehensive guidance for this purpose".

26 See Section 3 below.

27 For example Angola and South Africa are not members of the ICSID Convention.

28 For a recent decision which applied prescription based on Article 1116(2) of the NAFTA treaty, which also provides for prescription of claims after expiry of three years, see Apotex Inc. v. The Government of the United States of America (UNCITRAL), Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, 14 June 2013 at 99 para 300 -110 para 335. Article 1117(2) of the NAFTA Treaty. Available at https://www.nafta-sec-alena.org/Default.aspx?tabid=97&language=en-US), Article 26(1) of the USA Model BIT 2012. Available at http://www.ustr.gov/sites/default/files/BIT%20text%20for%20ACIEP%20Meeting.pdf (accessed 5 August 2014)), and Articles 23(2) and 26(1)(b) and 26(2)(c) of the Canada Model BIT 2004. Available at http://italaw.com/documents/Canadian2004-FIPA-model-en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2014)) also provide for prescription of claims after three years.

29 The USA Department of State Investment Climate Statement 2014 on Angola at 4. Available at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/228974.pdf (accessed 4 September 2014). Reports for other SADC States are available at http://www.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/2014/index.htm (accessed 4 September 2014).

30 Angola Investment Climate Statement 2014 at 4. Available at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/228974.pdf (accessed 4 September 2014).

31 Zambia Investment Climate Statement 2013 at 1. Available at http://www.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/2013/204763.htm (accessed 4 September 2014).

32 Mozambique Investment Climate Statement 2014 at 7. Available at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/227422.pdf (accessed 4 September 2014).

33 The use of clear language in a treaty is important, as it assists in the interpretation of a treaty in the event of a dispute. In terms of Art 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969 "(a) A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose".

34 Of course those investors who are covered by applicable BITS between their home States and the host State may still be access international arbitration via the BITS. Similarly, investors who are covered by investment agreements with host States may be able to access international arbitration via the investment agreements.

35 Arts 1121(1)(b) and 1121(2)(b) of the NAFTA, Art 26(2) of the USA Model BIT, and Art 26)(1)(e) of the Canada Model BIT contain similar provisions.

36 However, unlike Article 28(12), Article 29(17)(b) of the Model BIT does not specifically state that proceedings may be broadcast live. This literally means that State-State arbitrations can be broadcast live, while investor-state arbitrations cannot be broadcast live. It is doubted whether this is the real intent of the drafters of the Model BIT. The provisions to open arbitration hearings to the public and to broadcast hearings are also contained in Article 6 of the UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency in Investor-State Arbitrations of 2014.

37 Art 2(3) United Nations Charter. With regard to the settlement of investment disputes see for example UNCTAD "Dispute settlement course 2.2 selecting the appropriate forum" 2003. Available at http://unctad.org/en/docs/edmmisc232add1_en.pdf. Accessed 30 August 2014), and see also the overview of the UNCTAD course available at http://unctad.org/en/docs/edmmisc232overview_en.pdf (accessed 30 August 2014).

38 Art 4(e) SADC Treaty. In terms of the Treaty SADC Member States are also required to observe human rights and the rule of law (Art 4(d)); the sovereignty of other States (Art 4(a); solidarity, peace and security (Art 4(b); and equity, balance and mutual benefit (Art 4(d). Art 24 of the FIP provides that member states shall ".use their best endeavours, through co-operation and consultation, to achieve consensus in the interpretation, application and implementation of this Protocol".

39 Art 28(1) Annex 1 FIP; Art 29(1) Model BIT. For an introduction to alternative dispute resolution see UNCTAD "Investor-States disputes: prevention and alternatives to arbitration" 2010, available at http://unctad.org/en/docs/diaeia200911_en.pdf (accessed 30 August 2014). See also the sequel to this publication available at http://unctad.org/en/docs/webdiaeia20108_en.pdf (accessed 30 August 2014). For factors which lend momentum to alternative dispute resolution versus arbitration see UNCTAD IIA issues Note No. 2 June 2013 "Reform of investor-State dispute settlement: in search of a roadmap." Available at http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdiaepcb2013d4_en.pdf (accessed 30 August 2014).

40 Art 28 Annex 1 FIP; Art 28 and 29 Model BIT. For an introduction to investor-State arbitration see UNCTAD "Dispute settlement 5.1: international commercial arbitration" 2005, available at http://unctad.org/en/Docs/edmmisc232add38_en.pdf (accessed 30 August 2014). For recent arbitration statistics see UNCTAD IIA Issues Note No 1 April 2014. Available at http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdiaepcb2014d3_en.pdf (accessed 30 August 2014). For ICSID arbitration statistics see https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=ICSIDDocRH&actionVal=CaseLoadStatistics (accessed 30 August 2014).

41 Art 28(1) and (2) FIP; Art 28 and 29 Model BIT.

42 Some SADC States are parties to BITS which have investor-State dispute resolution provisions. Treaties are not taken into consideration in this article because their provisions are not available to all investors, as intended by the SADC FIP. They are only available to nationals of the member States to the treaty. Madagascar is not included in this article as it has just emerged from the suspension of its SADC membership.

43 S 16(1) Basic Law for Private Investment No 20/11 of 20 May 2011. In addition, the rights an investor, stemming from a treaty or an investor-state agreement, may also be asserted (s 16(5)).

44 Angola has recently passed a new investment law in the second half of 2015, of which an English version is not yet available. This law is therefore not considered here as it came into being after this article was finalised.

45 Art 8(1)(b)(ii) Constitution of the Republic of Botswana of 1966 as amended to 2002.

46 Art 38 Investment Code No 004/2002 of 21 February 2002 (English non-official version).

47 Art 37 Investment Code.

48 Art 38 Investment Code.

49 Art 17(2) Constitution of Lesotho of 1993 as amended to 2001.

50 Art 46 Constitution of the Republic of Malawi of 1994 as amended to 2010.

51 Ss 8(1)(c)(ii) and 17 Constitution of the Republic of Mauritius of 1968 as amended.

52 The International Arbitration Act 2008 as amended with effect from 1 June enables and regulates international arbitration in Mauritius. It does not however give an investor a right to international arbitration.

53 Ss 25(1)-25(2) Law on Investment No 3/93 of 24 June 1993.

54 S 25(2) Law on Investment.

55 S 25(2) Law on Investment.

56 S 13(4) Foreign Investment Act No 27 of 1990 as amended to 1993.

57 Ss 13(1)-(2) Foreign Investment Act.

58 Art 26(3)(e) Constitution of the Republic of Seychelles of 1993 as amended to 1996. In terms of Section 5(3) Seychelles Investment Act 31 of 2010, an investor may access such forum as is indicated by law or an investor-state agreement.

59 The Promotion and Protection of Investment Bill, 2013 (published in the Government Gazette, Vol. 581, No 36995 on 01 November 2013) is still going through the parliamentary process. Its provisions are therefore not included here.

60 The Arbitration Act 42 of 1965 provides for local arbitration of disputes. It does not however give an investor a right to arbitration.

61 S 21(a) of the Swaziland Investment Promotion Act 1 of 1998.

62 S 21(b) of the Swaziland Investment Promotion Act.

63 S 21(c)-(d) of the Swaziland Investment Promotion Act.

64 S 23(1) Tanzania Investment Act No 26 of 1997.

65 S 23(2)(a) Tanzania Investment Act.

66 S 23(2)(b) Tanzania Investment Act.

67 S 21 Zambia Development Agency Act No 11 of 2006. The Act in question is the Arbitration Act 19 of 2000. In terms of s 5(2)(a) and (b) of the Arbitration Act, a provision in a law (such as section 21 of the Zambia Development Agency Act in this case) which provides for a dispute to be referred to arbitration, amounts to an arbitration agreement, and parties to the dispute who invoke the arbitration provision are deemed to be parties to the arbitration agreement.

68 Ss 71 and 72 Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe of 2013 provide for an investor to approach the court regarding compensation for expropriation. However section 72(3) prevents a court from adjudicating on a dispute regarding compensation for expropriation of agricultural land (only compensation for improvements can be challenged).

69 Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe.

70 Mozambique and Tanzania. In Mauritius, despite having established the Mauritius International Arbitration Centre, neither the Mauritius Investment Protection Act 2000 as amended nor the Constitution of 1968 as amended provide for international arbitration.

71 This helps investors from non-ICSID States such as, Angola and South Africa, as they can access Additional Facility arbitration despite their home States not being members (Art 2(a) ICSID Additional Facility Rules 2006. Available at https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/StaticFiles/facility/AFR_English-final.pdf (accessed 10 August 2014).

72 Angola, DRC, Swaziland, Tanzania, and Zambia.

73 S 21 Zambia Development Agency Act. However, an investor can resort to applicable BITS or an investment agreement.

74 For example, the Mauritius-South Africa BIT. Available at http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/Download/TreatyFile/1991 (accessed 15 August 2014), provides for international arbitration, but the investment codes of these States do not provide for it.

75 It must be noted that BITs contain more than provisions for international arbitration. They also give foreign investors rights which are often not found in investment codes, such as the rights to free and equitable treatment, fair administration treatment, most favoured nation treatment, and full protection and security (see for example Articles 4, 5 and 9 SADC Model BIT).

76 See also Baseline Summary at 11. For a detailed analysis on the general challenges facing SADC, see Mapuva J & Muyengwa-Mapuva L "The SADC regional bloc: what prospects for regional integration?" (2014) 18 Law, Democracy & Development 22 at 35; [ Links ] Saurombe A "Regional integration agenda for SADC "caught in the winds of change" problems and prospects" (2009) 4 (2) Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology 100; [ Links ] Saurombe A "The role of SADC institutions in implementing SADC treaty provisions dealing with regional integration" (2012) 15 (2) Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal 453; [ Links ] Saurombe A "The European Union as a model for regional integration in the Southern African Development Community: a selective institutional comparative analysis" (2013) 17 Law, Democracy & Development 457. [ Links ]

77 There are basically two forums, being litigation and arbitration. Litigation is non-controversial from a state's point of view because a State will readily agree to it. SADC State practice shows that states provide more for litigation than for international arbitration.

78 See for example Baseline Summary at 11.

79 See for example Baseline Regional Report at 54 where it is said "In fact, evidence from interviews suggests that investment competition among member states remains high, and so there has been difficulty in gaining consensus on a regional investment policy framework. Member states will be reluctant to harmonise where this impacts their ability to compete and where it is not in the national interest to do so".

80 Baseline Summary at 54.

81 Baseline Summary at 11.

82 The provision states "An Investor may submit a claim to arbitration pursuant to this Agreement, provided that: (a) six months have elapsed since the Notice of Intent was filed with the State Party and no solution has been reached".

83 Anatolie Stati & others v The Republic of Kazakhstan SCC Arbitration (Case 116/2010) Award of 19 December 2013. This decision contrasts directly with, Tulip Real Estate Investment and Development Netherlands B.V. v Republic of Turkey ICSID Case No. 11/28 Decision on Bifurcated Jurisdictional Issue, and Award of 10 March 2014.

84 Kilic Insaat Ithalat Ihracat Sanayi Ve Ticaret Anonim Sirketi v Turkmenistan ICSID Case No. ARB 10/1 Award of 2 July 2013 at 73 para 6.3.12 - 74 para 6.3.15.

85 Tulip Real Estate Investment and Development Netherlands B.V. v Republic of Turkey ICSID Case No. 11/28 Decision on Bifurcated Jurisdictional Issue at 35 para 135.

86 This provision states "An Investor may submit a claim to arbitration pursuant to this Agreement, provided that: (a) .... (b) the Investor or Investment, as appropriate, (i) has first submitted a claim before the domestic courts of the Host State for the purpose of pursuing local remedies, after the exhaustion of any administrative remedies, relating to the measure underlying the claim under this Agreement, and a resolution has not been reached within a reasonable period of time from its submission to a local court of the Host State; or (ii) the Investor demonstrates to a tribunal established under this Agreement that there are no reasonably available legal remedies capable of providing effective remedies of the dispute concerning the underlying measure, or the legal remedies provide no reasonable possibility of such remedies in a reasonable period of time."

87 Even Article 26 of the ICSID Convention allows a State to make the exhaustion of local remedies a precondition for its consent to arbitration.

88 Art 28|(12) and 29(17) FIP.

89 See for example Article 6 of the UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency in Investor-State Arbitrations of 2014.

90 Treaty shopping is a practice whereby an investor selects a State wherein it has no economic activities as its State of incorporation. The purpose of this selection is to benefit from the BIT(s) which the selected State has with the State (s) wherein the investor intends to do business. The recent case of Yukos Universal Limited (Isle of Man) v The Russian Federation Interim Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility of 30 November 2009 PCA Case No AA 227 shows that a tribunal will not disqualify treaty-shopping if such practice is not prohibited by the relevant treaty.

91 Article 26(2) of the Model BIT states "Subject to prior notification and consultation with the other State Party, a State Party may at any time deny the benefits of this Agreement to an investor of another Party that is an enterprise of such Party and to investments of such investors if investors of a non-Party own or control the enterprise and the enterprise has no substantial business activities in the territory of the Party under whose law it is constituted or organised".

92 See Model BIT at 11 and 14.

93 But this submission does not ignore the fact that an investment code can be easily amended, unlike a BIT. Legislation can be amended at any time in accordance with the requisite parliamentary procedures, while a treaty requires the consent of both States to amend. Even if a treaty is terminated, its provisions may remain in force for years (see for example Article 12(3) of the South Africa Zimbabwe BIT which has a survival period of 20 years). Therefore a BIT provides a more stable regime than an investment code since it is not easily altered.

94 This provision states "State Parties shall ensure that investors have the right of access to the courts, judicial and administrative tribunals, and other authorities competent under the laws of the Host State for redress of their grievances in relation to any matter concerning any investment including judicial review of measures relating to expropriation or nationalisation and determination of compensation in the event of expropriation or nationalisation".

95 Mike Campbell Pvt Ltd & 78 others v Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe SADC (T) Case No 2/2007 Main judgment at 26.

96 Mike Campbell case at 26.

97 Mike Campbell case at 35.

98 Mike Campbell case at 35-37.

99 For a recent case see Franck Charles Arif v the Republic of Moldova (ICSID ARB No 11/23) Award of 8 April 2013.

100 This Article states that: "Subject to the provisions of paragraph 28.4, a State Party may submit a claim to arbitration seeking damages for an alleged breach of this Agreement on behalf of an Investor or Investment..."

101 Examples of advance consent provisions in regional treaties with advance consent are Article 26(3)(a) of the ECT, and Article 1122(1) of the NAFTA Treaty.

102 This is the approach adopted by Mozambique and Tanzania in their investment codes. See Table 1 in Section 3 above.

103 State practice as seen in investment codes may lend support to this view.

104 Article 2 of the Additional Facility Rules 2006. The Rules are available at https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/StaticFiles/facility/AFR_English-final.pdf (accessed 30 august 2014).

105 This is because UNCITRAL arbitration is available to investors of all nationalities, since only consent and not treaty membership is required for UNCITRAL arbitration (see Article 1 of the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules 2010).

106 They are Mauritius (1), Botswana (2), Seychelles (4), South Africa (5), Namibia (6) and Lesotho (10). See http://www.moibrahimfoundation.org/iiag/ (accessed 2 September 2014).

107 These are Angola, Zimbabwe, the DRC, and Swaziland. See http://www.freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/MapofFreedom2014.pdf (accessed 20 September 2014).

108 These are Malawi, Madagascar, Mozambique, Zambia, Seychelles and Tanzania.

109 Mapuva & Muyengwa-Mapuva (2014) at 36.

110 For an example of an investment ombud, see http://www.i-ombudsman.or.kr/eng/etc/site.jsp (accessed 4 September 2014).

111 See for example Saurombe (2013) at 465.

112 Saurombe (2012) at 476.

113 See Model BIT at 13, under commentary regarding "investor". The recent Yukos case shows that nationals of a State can incorporate entities abroad, and then use them to conduct business in the home State. In the event of a dispute with the home state, they then sue their home State, but in the name of their "foreign" entities. The Model BIT proposes that this practice be prohibited, and that shell companies must have substantial or substantive business operations in the State of incorporation (see the Model BIT for the definition of an "investor" at p11, commentary at 14, and Article 26(2)).