Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.19 Cape Town 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v19i1.6

The unresolved ethnic question in Uganda's district councils

Douglas Karekona SingizaI; Jaap De VisserII

IPhD, (Public Law), Head of Legal Research, Registry of Planning and Development, (Judiciary of Uganda)

IIProfessor of Law and Director, Dullah Omar Institute (University of the Western Cape)

1 INTRODUCTION

The Constitution of Uganda of 1995 (the Constitution) recognises 65 indigenous communities in Uganda.1 It aspires to integrate all the people of Uganda by directing that "[e]verything shall be done to promote a culture of cooperation, understanding, appreciation, tolerance and respect for each other's customs, traditions and beliefs".2 The Constitution posits five fundamental rights that are particularly relevant to our discussion. These are: equality and freedom from discrimination; respect for human dignity and protection from inhuman treatment; the protection of freedom of conscience and religion; the protection of minorities; and the right to culture and similar rights.3

Decentralisation to local government is often associated with two important drivers, namely, deepening democracy and pursuing development.4 In Uganda, a decentralisation agenda was pursued in order to achieve sustainable levels of development, improve the country's democratic governance, sustain political stability, and promote diversity.5 This article focuses on Uganda's quest to use decentralisation to promote the accommodation of diversity. It is a critical goal as the neglect or even suppression of diversity, be it ethnic, cultural or religious, can be linked to poverty, political despondency, alienation, and civil strife. It may even result in ethnic groups directly challenging the legitimacy of the state.6

This article examines the legal and constitutional framework for the election of district councils in Uganda because the design and practice of elections in Uganda has an impact on Uganda's ability to follow through on the promise of respecting and encouraging diversity through decentralisation. The article concludes that the law and practice surrounding the election of district councils reveal the political exclusion of ethnic minorities. It is argued that this is contrary to the stated policy objectives of decentralisation in Uganda and only serves to further promote the political dominance of the ruling party.

2 VALUE OF LOCAL DEMOCRACY

Elections are a means by which peoples' needs are gauged. They also manifest the ability of citizens to hold their leaders to account. It can be safely argued that a developmental path cannot be pursued effectively without democracy. There is little doubt that decentralisation to locally elected governments has great potential to deepen democracy for the benefit of development. In addition, local representative democracy may also play a key role in the development of political pluralism and the promotion of diversity. It is argued that political pluralism is better facilitated in a decentralised system of government than in a centralised form of government. First, the increased number of elected offices creates space for greater political participation by minority groups. Where a group feels politically alienated at the national level, pursuing political claims at the local level becomes a logical option.7 Secondly, a decentralised system of government creates smaller orders of government which makes for greater accessibility; electoral participation is less cumbersome than participating at the national level.8 This is particularly important as a large number of people (in most cases minority and vulnerable groups) who would ordinarily be potential candidates are easily disqualified for national election on the basis of onerous electoral rules and high electoral thresholds. Thirdly, local democracy has great potential to promote cooperation and respect across the political spectrum. By its very design, local representative democracy is likely to produce different results in different jurisdictions, resulting in political diversification. Yet, after elections, local political leaders, irrespective of their political or ethnic inclinations, must work together under the broad umbrella of the nation State and in the pursuit of service delivery and development. In that sense, multiparty democracy can be learned through practising local democracy. The Constitution of Uganda, with its elaborate provisions on decentralisation and local democracy, is very much alive to this democratic potential.

2.1 Importance of inclusiveness in the design and practice of local democracy

Reynolds identifies six considerations that are crucial in the design of the electoral system in fragmented societies.9 It is argued that these considerations are particularly relevant for the enquiry undertaken in this article, namely, the assessment of the electoral system for local government in Uganda. The six considerations relate to: (a) representativeness; (b) accessibility; (c) reconciliation; (d) accountability; (e) inclusive political mobilisation; and (f) stability of government.

2.1.1 Represen ta tiven ess

The local government electoral system should fairly represent the consent of local communities. This better promotes local political legitimacy than an electoral system that is exclusionary and factional.10 The electoral system must be capable of offering organisations that subscribe to divergent political views a fair chance to compete for power and voice. It is argued that a local government's electoral design must make every effort to be as inclusive as possible of the various sectors of the population. Particular attention should be paid to marginalised groups, such as, women, youth, disabled persons, and indigenous communities.11 This is critical to avoid the "tyranny of the majority" which can have a stultifying effect on democracy, particularly at a local level.

2.1.2 Accessibility

The electoral system should be accessible to candidates as well as voters. The requirements for participating in the elections as a candidate should not be unduly restrictive and the electoral system should be designed in a manner that makes local citizens feel that their votes count.12

2.1.3 Reconciliation

In countries emerging from a history of political conflict, the electoral system for local government can play a role in promoting reconciliation and avoiding confrontational politics at the local level.13 It is difficult to predict what type of electoral system this requires. However, an electoral system that includes elements of proportional representation may function as a conflict regulating mechanism that contributes to fostering peace and democracy in post-conflict states.14 Indeed, as observed by Nohlen, Krennerch and Bernhard, "...majority representation in segmented societies runs the risk not only of exaggerating ethnic conflicts, but also of sharpening ethno (sic) regional polarization".15 In countries like Namibia and South Africa, where the electoral system was part of the negotiations towards independence, proportional representation was considered as necessary for national integration and consensus building.16

2.1.4 Accountability

The electoral system also influences how local communities can keep their councillors and councils accountable.17 Accountability mechanisms, facilitated by the electoral design, are critical to address underperformance and corruption.18 It is argued that local accountability is more likely to take root if a local government electoral system facilitates political competition between multiple alternatives.

2.1.5 Inclusive political mobilisation

The ultimate aim of any electoral system should be to guarantee the free expression of the will of the voters and translate that expression into a legitimate governance structure.19 It is thus argued that the electoral system should not exclude any person or organisation from participating in elections as a voter or a candidate, on the basis of ethnic origin or religious affiliation. As this article will highlight, this must be balanced against the argument that political mobilisation, based on broad local or national interests, better promotes reconciliation than political mobilisation around ethnic, religious or geographical enclaves.20 Ethnic interests are better catered for when political mobilisation is inclusive and wide rather than narrow and parochial. For instance, where a country's electoral system only produces victories for one dominant social group, the interest of other, subservient social groups may be ignored without any political risks.

2.1.6 Stability of government

The electoral system for local government should also promote stability by ensuring that local governments are empowered to govern and take decisions.21 This means that the electoral system should enable the formation of strong stable local governments with capacity to initiate and follow through on policies and laws. Such a government presupposes the ability of an electoral system to create majority local governments. As Omara-Otunnu explains, the reality of democracy is that 'it can operate successfully only in a climate of tolerance and flexibility in which the inherent diversity of society is accepted and given reasonable latitude.'22 The next section of this article focuses on the issue of ethnic diversity in Uganda before an assessment of Uganda's electoral system for district councils commences.

3 ETHNIC DIVERSITY IN UGANDA

The last available official census report in Uganda was for the census conducted in 2002. The report indicated a population of 23,841,300.23 The provisional results of the 2014 census report indicate that Uganda has a population of approximately 35 million people (an increase of 31.882% since 2002).24

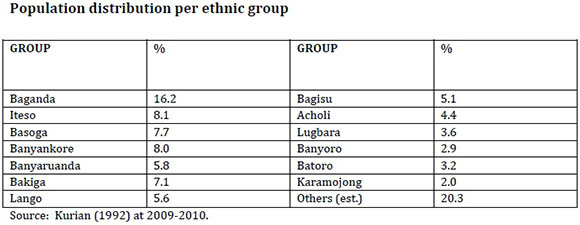

Kurian gives the percentage distribution of population per ethnic group for 13 ethnic groups in Uganda. There also is a category for 'others'. According to Kurian, 20.3% of Uganda's total population is categorised as 'others'.25 The assumption is that those categorised as 'others' do not fit into the mainstream or dominant ethnic groups of Uganda. Using the 2014 provisional population census results together with Kurian's study, it can be that out of the 35000000 people in Uganda, 7105000 (20.3 per cent of the total population) belong to the non-dominant ethnic groups (minority), while the remaining 27895000 (79.7 per cent of the total population) belong to the dominant ethnic groups (majority).

There are no legal definitions of the terms "majority ethnic groups" or "minority ethnic groups." However, the 2002 population census results, like all the previous population census results, use the terms "major ethnic groups" and "others." In the absence of any legal definition of the two terms, the national population census results are a good guide.

Over the last two decades, Uganda has experienced relative stability,26 with the civil war in the northern parts of the country being the obvious and tragic exception. 27During that period, there also appeared to have been very few incidents of overt ethnic tension. It seems, however, that anger and frustration are growing, particularly in the southern parts of the country.28 From 2001 to 2010, there have been an unprecedented number of protests against the incumbent government.29 A key example is the clash between the supporters of the Buganda Kingdom and the military and police in 2010, which led to injuries and loss of life.30 Inter-ethnic land-related tensions also appear to be on the increase, as evidenced by incidents, such as, the land wrangles between the Basongola pastoralists and the Bakonjo cultivators in the Kasese district, on the one hand,31 and the Bakiga (the 'bafuruki') and the Banyoro in the Kibale district, on the other32. This anger and frustration may be related to an increase in corruption related incidents, political violence and political intolerance.33 All of these have fomented a subtle but growing resistance against the incumbent government. This article discusses the connection between these manifestations of growing resistance against the incumbent government and certain fundamental flaws in the institutional design of local government, particularly the legal prohibition on the use of a candidates' ethnic identity in the political processes. It is also arguable that the legal framework that seems to target a candidate's ethnic identity is linked to the ruling party's discouragement of genuine political mobilisation that may threaten its grip on State power.

4 TRANSITION FROM THE MOVEMENT POLITICAL SYSTEM TO MULTIPARTY DEMOCRACY

4.1 Introduction of the Movement Political System

In order to understand the relevance of the legal prohibition on ethnic identity in politics, it is useful to trace the history of multiparty democracy in Uganda, going back to the assumption of power by the National Resistance Movement/Army (NRM/A) in 1986. The NRM/A removed General Lutwa's military junta, and the solemn promise to Ugandans was that the change would not be "a mere change of guards, but a fundamental change".34 Onyango-Obbo explains the historical and political context of the events preceding the NRM government thus: "Uganda was broken, bloodied by war, poor, and its citizens exhausted by marauding military goons when Museveni took power. They [Ugandans] were willing to support NRM as long as it didn't take the country back to the nightmarish past. And they were willing to be forgiving of any crime that was not as worse as Amin's or Obote II's."35 This view is supported by Rubongoya who links the political dominance of the ruling NRM to the political vacuum that had been created by the long spell of the collapse of the post-independence State. Accordingly, the devolution of State power to district councils, as one of the State reform measures adopted by the NRM in the 1990s became a necessary "institutional bridge" that aided the ruling party to restore legitimate rule in the country as it consolidated itself into power.36 Immediately after the overthrow of the military government, the NRM government legalised itself by proclamation, while at the same time suspending all political party activities.37 A consensus seemed to emerge that a sustainable democratic future required a broad-based form of government that was inclusive and democratic. The ground was therefore prepared for the establishment of the "non-party political system" that was later entrenched in the Constitution.38

The promulgation of the Constitution was preceded by the work of the Odoki Commission whose mandate it was to gather the views of the people and make recommendations to the Constituent Assembly (CA).39 One of the many issues on which the Odoki Commission needed to pronounce was whether the new dispensation should allow for political parties to compete in local government elections. According to the Odoki Commission, there was no consensus amongst the members of the public as to whether local government elections should be open to political party competition.40Drawing on the history of multiparty politics in the 1960s and later in 1980, the Odoki Commission explained that much of the political instability could be attributed to particular political parties, such as the Uganda People's Congress (UPC).41 Treading carefully, the Odoki Commission recommended that under a multiparty system local governments should offer a platform for all political parties. However, it was also recommended that, until the introduction of multi-party politics, local government elections should be organised according to the non-party political system, given the relative peace and unity that had obtained in many local communities.42 Ultimately, what was introduced in the Constitution was a system called the Movement Political System.

4.2 The constitutional limitation on political pluralism before the amendment

The Constitution prohibited political parties from engaging in any political activities, and specifically prohibited political parties from sponsoring candidates in national or local elections from carrying out any activities that would "interfere with the Movement Political System".43 There was arguably very little distinction between the government of the day and the Movement Political System. Thus, the structures of the Movement Political System were for all intents and purposes a "rival" and not a "shadow" government. Makara argues that "...although the NRM (until 2005) had claimed to be a movement and not a one-party state, it did operate like the latter".44 Omara-Otunnu explains that the NRM's "hegemonic control of the population ...proved to be incompatible with the needed conditions of democracy."45 The discussion bellow examines the status of local democracy in Uganda after the re-introduction of multiparty politics, and the role of ethnicity in Uganda's district councils.

The absence of a strong middle class is the most common argument against multiparty politics in Uganda's system of local government.46 Writers on the topic, including President Yoweri Museveni, are of the view that independence political parties were formed largely around "tribes" and religion as common rallying features. He argues that the tribal nature of most post-independence political parties narrowed the ideological and philosophical foundations of political pluralism to petty ethnic identities. Thus, ethnic interests rather than national or class interests endangered the post-independence economic and social transformation of the country.47 Unlike the developed countries that have industrialists and workers, Ugandan society would be incapable of harnessing the advantages of political pluralism on account of the absence of class consciousness. This is a result of the fact that Ugandan society is characterised by the pre-industrial ideology of the peasantry class.48 The real fear was that, instead of bringing healthy political competition, political pluralism would result in ethnic tensions.49 In a country with no advanced political economy to sustain multiparty democracy, the spectre arose of political parties freezing ethnicity and ultimately threatening the nation State.50 The above views find support in Barro's study which uses elections as a measure of electoral rights to explain the essential determinants of democracy in competitive politics.51 According to Barro, in the absence of a strong middle class, differences in attributes, such as, ethnicity, language, and culture, negatively affected a country's quality of democracy. He argues that "there is some indication that more ethnically diverse countries are less likely to sustain democracy", on account that they are prone to factional politics. However, he acknowledges the role of ethnic diversity in mitigating political inequities in a democracy.52 Many of Uganda's parties at the time indeed bore the imprint of specific tribal and/or religious groups. For example, the UPC was dominated by non-Buganda/Anglican Christians. The Democratic Party (DP) was dominated by Baganda/Catholics, while the Conservative Party (CP) was dominated by Buganda Kingdom monarchists.53

It is conceded that Uganda's "tribalised" post-independence political parties as well as the divisive socio-economic power relations struggles, in part account for the country's violent history. The fractionalised political groups based on petty ethnic interests not only undermined the very foundation for political pluralism in Uganda but also seemed to threaten Uganda as a nation State.54

4.3 Introduction of multiparty democracy

As a result of persistent pressure on the government, multiparty politics was reintroduced ten years after the Constitution was promulgated. The pressure came from different stakeholders, such as academics, civil society, religious groups and political parties, but also from the international donor community. The Movement Political System was changed to the Multiparty Political System.

This reform commenced with a constitutional amendment55 which catered, amongst other things, for the extension of the Presidential term limits, a political move described as the "purification of the Movement".56 The amended Constitution, in its current form, now provides for two main political systems, namely, the non-party political system (or the Movement Political System) and the pluralistic political system (or the Multiparty Political System).57 The choice is left to the voters who may express their preference in an election or a referendum. Parliament may also change the political system by majority vote. However, the decision must be supported by a resolution of the majority of councillors in every district council.58 At least 50 per cent of the district councils in the whole country must support such a resolution.59 Following the 2005 constitutional amendment, the Multiparty Political System was adopted.60 The Constitution does place an important limitation on the Multiparty Political System by warning political parties to be of a "national character" and not based on "sex, ethnicity, religion or other sectional division".61

4.4 Statutory mechanisms to support the Multi-party Political System

The Multiparty Political System is further regulated by statute law. The Political Parties and Organisations Act of 2005 (PPOA) determines a framework for the establishment and operation of political parties.62 A political party or organisation that wishes to engage in political activities (which may include sponsoring candidates for national or local elections) must register.63 The Electoral Commission is mandated to oversee the registration of political parties64 and also has the authority to refuse to register an aspirant political party.65 It oversees the winding up66 and/or deregistration67 of political parties. The PPOA reiterates the provisions of Article 71(1) (b) of the Constitution by prohibiting the formation of political parties "based on sex, race, colour, or ethnic origin, tribe, creed or religions or other similar division".68 Further, it prohibits the use of words, slogans or symbols which might arouse any of the above divisions.69Under the PPOA, a political party which violates section 5 thereof not only risks the disqualification of its candidates but also the imposition of a fine not exceeding 72 currency points and/or imprisonment not exceeding three years.70 In addition, violation of the above provision may result in the rejection of a political party's application for registration as a political party or organisation, in addition to the possibility of it being wound up and/or deregistered.71

In other words, Parliament, under the mandate of the Constitution, prohibits the expression of ethnic, religious or cultural differences and thus further entrenches this as a feature of the plural political system. This principle is also followed through in local government. Local government elections are regulated, in the main, by the Local Governments Act (LGA).72 This Act, too, prohibits the use of any colours or symbols that have tribal or religious affiliation or "any other sectarian connotation" as a basis for one's candidature for election or in support of ones campaign.73 Under the LGA, individual candidates who violate this provision not only put their candidature at risk but also risk the imposition of a fine not exceeding 10 currency points and/or t imprisonment not exceeding two years.74 In other words, the government of Uganda did not want the re-introduction of multiparty politics to open the door for ethnic mobilisation. In fact, it imposed an outright ban on party political campaigning around ethnic, religious or cultural matters. It is argued that the regulation of political parties that targets a person's ethnic identity defies the theory stated in part 2.1 above that calls for an electoral system that is representative, accessible and capable of fostering an inclusive political mobilisation.

5 THE NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT'S POLITICAL DOMINATION AND UNEASY RELATIONSHIOP WITH ETHNIC DIVERSITY

5.1 Introduction

The discussion below briefly examines recent election outcomes in order to show the overwhelming majorities of the NRM in both national and local council elections, on the one hand, and steadily dwindling voter interest, on the other. The discussion also shows a disjuncture between the ethnic composition of the country and the representation of the various ethnic groups in the district councils.

5.2 NRM hegemony in national and local elections

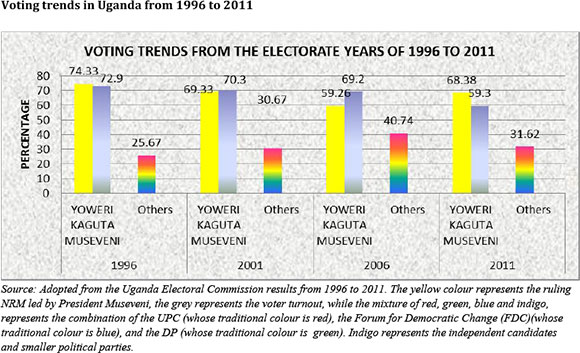

The Table below shows the Presidential election results between 1996 and 2011, indicating landslide victories for the NRM in all four elections. The Table also shows that voter interest has been on the decline with voter turnout in the 2011 elections being slightly lower than 59.6 per cent compared to an average of 70 per cent voter turnout in the 2001 and 2006 elections. It is also noted that between 1996 and 2011 the President's share of the votes declined from 75 per cent to 68 per cent.75

The picture in local government is very much, the same with the NRM winning the overwhelming majority of district council seats. For example, as of 2005, only three district councils out of 70 were controlled by opposition leaning chairpersons, while in the 2006 local government elections, only 15 out of 84 district council chairperson seats were won by opposition parties despite the fact that the ruling party's share of the national vote had statistically declined.76 In the 2011 local government elections, 85 out of a total of 112 district council seats were won by the ruling party, while the remaining seats were shared between the opposition parties and independent candidates.77 It is also argued here that an electoral system that encourages one political party to dominate the political space is incapable of fostering reconciliation and accountability, as argued in part 2.1 above.

The desire of the ruling party to dominate both the national and local elections may also be illustrated by the central government's decision to centralise the administration of Kampala City. Since the commencement of decentralisation, Kampala City has been part of the local government system, and treated as having the status of a district. Its five divisions were considered sub-counties. Before 2005, Kampala City formed part of the local government structures and was known as Kampala City Council (KCC). It was regulated in the main by the LGA, with structures and powers similar to those of any other district council. The elected political leader of KCC was the City Mayor, while the administrative head was known as the City Town Clerk.78 With the amendment of the Constitution in 2005 and the adoption of the Kampala Capital City Act 2010 (KCCA), the administration of Kampala, designated as the Capital City, was revested in the central government.79 The Constitution now vests powers in Parliament to determine the boundaries of the Kampala City Council Authority80 and parliament is also empowered to determine its administration and development.81 Whereas administrative efficiency might have been the reason for the re-centralisation of the Kampala City, given the evidence of its past mismanagement,82 the evidence of political undercurrents leading to the change of status is too overwhelming to ignore.

Since 1996 the opposition has won the majority of the elective seats of Kampala City. In fact, in the last local council election of 2006, the ruling party managed to win only one in five council seats, representing 20 per cent of all the seats.83 In the 2011 national and local council elections, the Lord Mayor's seat was won by the opposition party with 64 per cent of the votes cast. However, the ruling party won the majority of the city council seats.84 The decision by the central government to legally take over the control of Kampala City is mainly explained by political reasons rather than the desire to improve the management of the city.85 According to the President, Kampala voters had hanged themselves by voting for Mr Lukwago and other opposition leaning politicians. The President explained that by re-centralising the city administration he had "cut them off from the ropes" (sic).86 It is argued that the ruling party's inability to politically control the city in the past is explained in part by the numerical strength of the Baganda ethnic group as a voting bloc within the city.

The controversy surrounding the removal of the Lord Mayor of the Kampala City Council Authority from office is evidence of the highly charged political context/animosity between the central government and the elected political leaders of Kampala City.87 In 2013, the Minister for Kampala Capital City Authority appointed a Tribunal chaired by a High Court judge to investigate the allegation against the Lord Mayor of abuse of office and incompetency. The Tribunal found the Lord Mayor guilty on eight of the 12 impeachable offences.88 The Lord Mayor was subsequently "impeached"89 and his seat declared vacant.90 The Tribunal's report, the decision to impeach the Lord Mayor, and the declaration by the Attorney General, the Executive Director (ED) and the Minister, that the Lord Mayor's seat was vacant have been challenged in the High Court.91 Given the strict nature of the sub judice rule in Uganda, no further comments are made on the matter.92 It is further argued that an electoral system that does not protect the political autonomy of office bearers in a local democracy not only defies the core definition of local democracy as discussed in part 2 above but is also incapable of creating stable governments as argued in part 2.1. It also blurs local democracy as inflexible and intolerant.

The history of devolution in Uganda lies at the heart of the explanation of this hegemony. As explained above, the NRM/A effectively banned political parties and their activities upon capturing State power in 1986. It was in this environment of severely restricted political party activities that the process of devolution of powers to district councils commenced.93 The suspension of political party activities helped the ruling party to dominate the political space at both the national and local council levels. Under the non-party political system from 1986 to 2005, local governments were mechanisms of the central government hegemony.94 This continued after the introduction of the multiparty system. Districts that supported the ruling party were afforded higher levels of political autonomy than districts that showed support for opposition parties.95Lambright argues: "Popular and elite support for the ruling party directly influences councils' ability to effectively translate policy into outputs and to respond to the needs of their constituents".96 This indicates that when it comes to local elections, support for a political party that is in opposition to the national government produces no political dividends. The political space at both national and local levels is thus dominated by the ruling party and the interest in elections seems to be dwindling slowly.97 Two important developments in the local government sector connect this dominance to the NRM's uneasy relationship with ethnic diversity.

The first development is the early move to neutralise ethnicity by depoliticising traditional leadership. Right from the onset of the decentralisation programme, the central government chose to exclude traditional and cultural leaders from it. In fact, the Odoki Commission recommended not to involve traditional leaders and their institutions in national and district council politics, and rather confined traditional leaders to "purely cultural and developmental roles."98 Article 246 (2) (e) of the Constitution provides that "a person shall not, while remaining a traditional leader or cultural leader, join or participate in partisan politics". In the African context, culture and ethnicity are almost always intertwined and the prohibition of traditional leaders' participation in politics was thus an early move to legally and politically neutralise ethnicity.99 The second development suggests that the central government engaged with ethnicity but arguably for the sake of political expediency. From the inception of the decentralisation programme in 199 3,100 the central government unilaterally created many districts.101 There are now 122 districts in Uganda.102 The aim of the creation of many additional districts was, in part, to weaken strong ethnic groups. An economically stronger and/or more populous district can compete politically with the central government better than an economically weaker or less populous one. In fairness, the consideration of culture and ethnicity in the drawing of local government boundaries is not uncommon and may enable communities to participate in local politics with which they can identify.103 However, the evidence of the creation of ethnic based districts by the central government in Uganda seems to be diametrically opposed to its official decentralisation policy framework which aimed to exorcise ethnicity altogether.

As Omara-Otunnu laments, the NRM's quest to dominate the political space using ethnicity as a wild card merely created new forms of "ethnic chauvinism" that significantly threaten the promise of democracy.104

5.3 Representation of minorities on district councils

As indicated earlier, 20.3 per cent of Uganda's population belong to minority ethnic groups, with 79.7 per cent belonging to the majority ethnic groups. However, the composition of district councils across the country seems to bear no semblance to these demographic realities as the examples below indicate.

The Election Commission's local government election results 2011 indicates that there was not a single councillor from the Batwa ethnic group in the Kabale and Kisolo district councils, districts that are inhabited by the Batwa ethnic group. In fact, in a recent report, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) expressed concern about the absence of the Batwa, as a special interest group, in the Kabale and Kisolo district councils. It concluded that, given the dominance of other ethnic groups, it is unlikely that the Batwa people will ever have a chance to be elected even at the lowest local council level.105 The Ik in the Kaabong district, in the Karamoja region (a predominantly Karamanjong speaking district), is another example. The Ik people, with a population of about 11,272 in 2002 (with an estimated 31.882 per cent increase by 2014), are represented by only two Ik speaking councillors (one male and one female) in the Kaabong district council. The two councillors in fact represent Kamion sub-county, an area populated by the Ik people. The Nubians are a further example. The Nubians are mainly found in Bombo Town, Luwero district, and Arua district. They have a strong Islamic culture.106 According to the 2002 Uganda Population Census Results, the Nubians had a population of 37,000 people in 2002 (with an estimated 31.882 per cent increase in 2014).107 The Arua district council (with a population of 413,100 people in 2002 and estimated to increase by 31.882 per cent in 2014)108 and the Luwero district council (with an estimated population of 336,600 people in 2002 and estimated to increase by 31.882 per cent in 2014),109 have no Nubian speaking councillor. The last example is that of the Basongora people. The Basongora (estimated to be about 11,000 with an estimated increase of 31.882 per cent in 2014),110 are mainly a pastoral community found in Kasese, a district dominated by the Bakonjo ethnic group (which is estimated to consist of 533,000 people and estimated to increase by 31.882 per cent in 2014).111 Of the 51 district councillors in the Kasese district council, only one is Musongora speaking.112

The underrepresentation of minority ethnic groups in the leadership of district councils is even starker: not a single district council is headed by a chairperson from any of the minority ethnic groups. Again the principle stated in part 2.1.1 above that calls for a representative local democracy is defied.

6 ASSESSING UGANDA'S TREATMENT OF ETHNIC DIVERSITY IN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AS A MEANS OF THE NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT'S DOMINANCE

Most States in Africa are amalgamations of various ethnic nationalities, fused together at the time of colonisation and given "legitimacy" at independence. Often ethnic groups were suppressed immediately after independence from their colonial masters.113 The question that arises here is: how can different ethnic groups share power when some of them may be both numerically and economically stronger than others?

Accommodation of ethnicity in the process of devolution of powers is often rejected. National development interests are feared to become subordinate to ethnic or regional autonomous governance and identity demands.114 In this respect, ethnicity is viewed as a retrogressive notion, and undesirable in the process of attaining development goals.115 Strong autonomous lower orders of government, so the argument goes, exacerbate ethnic tensions and national disintegration.116 In devolution, ethnic groups may find the platform to question the legitimacy and existence of the nation State.117 In addition, the use of decentralisation to accommodate ethnicity may backfire as it could very well create "artificial majorities" in specific regional or local communities. This creates "minorities within minorities" and sets the scene for the new "majority" to discriminate against those who become minorities within local governments.118

It is argued that the above arguments are less tenable with regard to decentralisation to local government than they are with regard to decentralisation to regional or state governments. Accommodating ethnic interests through decentralisation to lower orders of government is unlikely to threaten nation State identity.119 It is rather an incentive for political stability.120

In Uganda, the provisions of the Constitution, the PPOA and the LGA consider the slightest expression of ethnic or cultural belonging as an impediment to an honest political engagement during local government elections. However, there is no reason why the framing of local electoral issues through the prism of local level tribal or ethnic concerns is in and of itself anathema to local democracy, and deserving of criminal and electoral censure.

The argument that ethnic diversity negatively affects district council performance and breeds conflict within district areas can be disputed. Lambright finds that "ethnic or linguistic diversity does not systematically explain differences in the performance of Uganda's district councils".121 Rather, he finds that apparent evidence of ethnic conflicts in some districts could be attributed to "local populations about indigeneity rather than simply the level of ethnic diversity".122

Certain ethnic groups, such as the Baganda, have their own cultural anthems and emblems. To label the use of ethnic or religious symbols as "sectarian and divisive" and, essentially, criminal, seems antithetical to the very spirit of local government democracy and the promotion of inclusiveness. In Uganda, ethnicity is manifested primarily in an ethnic group's attachment to land, culture and religious rites. The limitation of the expression of ethnicity in district council politics implies that ethnic minorities are not able to assert their land, cultural and religious rights at local level. There may very well be a correlation between the above phenomenon and the increasing incidence of land evictions of ethnic minorities, usually referred to as "peasants" by landlords from the dominant ethnic groups, and the resultant land related violence in the country.123

At the very least, the complete absence of minority groups, such as, the Batwa, the Ik or the Nubians, from representation in district councils suggests that minorities are dealt a bad hand by the electoral framework with its outright ban on the expression of ethnic, cultural or religious ideas. It is argued that this obstructs the realisation of the promise of the Constitution. This blanket prohibition should be reconsidered. The fact that it is virtually unimaginable that a Mutwa, an Ik, a Nubian or a Musongora will ever be elected as a chairperson of any district council in Uganda is problematic. Continued feelings of exclusion on the part of minority groups, whether defined on the basis of gender, age, disability or ethnicity, do not contribute to the building of a lasting solution for Uganda's developmental challenges, and it is suggested that government and political parties in Uganda should pay specific attention to bringing minority ethnic groups into the political mainstream. The continuous exclusion of the ethnic minorities in district councils only serves to reinforce the ruling party's political dominance in the country.

* This article was written while I was an LLD student at the University of the Western Cape. The authors are grateful to the Ford Foundation, Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and the National Research Foundation for making this research possible, and to Professor Israel Leeman for his helpful comments on an earlier draft.

1 Art 10(a) read together with the Third Schedule.

2 See the Constitution, the National Objectives of Directive Principles of State Policy No 3.

3 See generally the Constitution, Chap Four.

4 Decentralisation has also been associated with pressure to restructure as a precondition for financial assistance from developed countries and the World Bank. The World Bank study on Uganda's district management (Washington DC: World Bank 1992) at 2 focused on the Structural Adjustment Programme as a means for macro-economic management of the national economy, which operated on the assumption that the country's public sector was too large, and required an enabling environment for a market economy. The Study recommended that the decentralisation programme in Uganda had to focus on supporting macro-economic reform in order to ensure management efficiency, popular participation at the local level, and improved financial performance through increased revenue generation and rational expenditure decisions. See also Makara S Decentralisation and urban governance in Uganda University of the Witwatersrand (2009). [ Links ]

5 Lambright G Decentralization in Uganda: explaining successes and failures in local governance (Boulder: First Forum Press/Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc 2011) at 19. [ Links ]

6 See generally Mamdani M Citizen and subject: contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism (Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press 1996). [ Links ]

7 Kymlicka W "The global diffusion of multiculturalism: trends, causes and consequences" Paper presented at International Conference on Leadership, Education and Multicultuaralism in Armed Forces, La Paz, Bolivia (2004) at 27. [ Links ]

8 Golooba-Mutebi F "Local councils as political and service delivery organs: limits to transformations" in Nakanyike M et al (eds) Transformations in Uganda (Kampala: Makerere Institute of Social Research Cuny Centre 2002) at 23.

9 Reynolds A Electoral systems and democratization in Southern Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1999) at 91-92.

10 Reynolds (1999) at 92.

11 Markku S "Good governance in the electoral process" in Schmidt H-O et al (eds) Human rights and good governance: building bridges (The Hague/ London/New York: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 2002) at 209. [ Links ]

12 Reynolds (1999) at 92.

13 Reynolds (1999) at 92.

14 Murray C "Recognition without empowerment: minorities in a democratic South Africa" (2007) 5 IJCL 699 at 709. [ Links ]

15 Nohlen D Krennerch M & Thibaut B "Elections and electoral systems in Africa" in Nohlen D, Krennerch M & Thibaut B (eds) Elections in Africa: a data handbook Oxford: Oxford University Press (1999) at 18. [ Links ]

16 Nohlen, Krennerch & Thibaut (1999) at 18.

17 Reynolds A (1999) at 92.

18 Markku (2002) at 217.

19 Markku (2002) at 223.

20 Reynolds (1999) at 92.

21 Reynolds (1999) at 92.

22 Omara-Otunnu A "The struggle for democracy in Uganda" (1992) 30 The Journal of Modern African Studies 443 at 444. [ Links ]

23 Bahemuka S et al (eds) The 2002 Uganda population and housing census, population dynamics (Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2006) at 8. [ Links ] As a practice, population census exercises in Uganda are conducted every 10 years. The 2014 population census should have been conducted in 2012. However, due to financial and budgetary constraints, the exercise was delayed for two years. Even then, only provisional results have been provided. It is noted that the provisional results do not indicate the breakdown of the total population to ethnic groups.

24 See Government of Uganda (GOU) National population and housing census provisional results (Kampala: National Bureau of Statistics 2014) at 1.

25 Kurian G T (ed) Encyclopedia of the Third World 4 vol III, (New York: Facts on File 1992) at 2009-2010. [ Links ]

26 Siegle J & O'Mahony P "Assessing the merits of decentralization as a conflict mitigation strategy" paper prepared for USAID's Office of Democracy and Governance (2006) at 47.

27 The northern part of the country, in political terms, is predominantly Luo speaking, although it has ethnic groups of the Acholi and the Lango speaking peoples. In geographical terms, however, the northern part of the country also includes parts of the West Nile Region. From 1986-2009, the northern region witnessed one of the most horrific civil conflicts in Uganda that involved Uganda government forces, (formerly National Resistance Army (NRA), now the Uganda People's Defence Forces (UPDF) and the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) under Joseph Kony. The war, although fought mainly in the Acholi region, equally affected the entire northern region. For details on the northern Uganda conflict, see generally Dolan (2009).

28 See "Deaths in Uganda forest protest" BBC News available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6548107.stm, (accessed 6 April 2007); "Uganda MPs angry at forest plan" available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6478829.stm (accessed 6 September 2007); United States of America report on Uganda at http://www.scribd.com/doc/30655494/Clinton-Report-42710#about, ( accessed 4 May 2010); "Chogm debate flops again" The Daily Monitor available at http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/917286/-/wymahm/-/index.html (accessed 14 May 2010). See also Esrom William Alenyo v The Electoral Commission & another Court of Appeal Election Petit Appeal No. 9 of 2007; Kirunda Kivejinja Ali v Katuntu Abdu Court of Appeal Election Petit Appeal No 24 of 2006.

29 "Museveni an obstacle to democracy" The Independent available at http://www.independent.co.ug/index.php/cover-story/cover-story/82-cover-story/2824-museveni-an-obstacle-to-democracy- (accessed 29 April 2010).

30 "The riots were not about Kabaka Mutebi and Kayunga" The New Vision available at http://www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/20/695436 (accessed 25 September 2009).

31 See "Land wrangles between Kasese Basongola and Bakonzo Resumes" Weinformers available at http://www.weinformers.net/2011/06/02/land-wrangles-between-kasese-basongola-and-bakonzo-resumes/ (accessed 2 June 2011).

32 See Lambright (2011) at 28. The term a 'mufuruki' (or plural form the 'bafuruki'), is a derogatory one that refers to the "non-indigeneity" of a given people in an area of Uganda.

33 See United States of America report on Uganda available at

http://www.scribd.com/doc/30655494/Clinton-Report-42710#about (accessed 4 May 2010); "Chogm debate flops again" The Daily Monitor available at http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/917286/-/wymahm/-/index.html (accessed 14 May 2010). See also "Uganda public order bill is 'blow to political debate'" The BBC available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-23587166 (accessed 7 July 2013).

34 President Museveni's speech on February 1986 cited in Kanyeihamba G Constitutional and political history of Uganda: from 1994 to the present (Kampala: Centenary Publishing House 2002) at 200-238.

35 Onyango-Obbo, C 'Kony has survived for 25 years by stealing Museveni's secrets' http://www.monitor.co.ug/OpEd/OpEdColumnists/CharlesOnyangoObbo/Kony+has+survived+for+25+years +by+stealing+Museveni+s+secrets/-/878504/1411184/-/7nm435z/-/index.html (accessed 8 July 2013).

36 Rubongoya J Regime hegemony in Museveni's Uganda: Pax Musevenica (London: Palgrave Macmillan 2007) at 1-16. [ Links ]

37 See Legal Notice No1 of 1986.

38 The Constitution, art 70.

39 See Uganda Constitutional Commission Statute 5 of 1988 ss, 4 & 5.

40 GOU (Ministry of Local Government) (MOLG) Decentralization: the policy and its philosophy (Kampala: Ministry of Local Government/Decentralization Secretariat 1993) at 518.

41 Museveni Y What is Africa's problem? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2000) at 7. [ Links ]

42 GOU Odoki Constitution Commission Report (Entebbe: Government Printer 1993) at 519.

43 The Constitution art 269; see Lambright (2011) at 28.

44 Makara (2009) at 64.

45 Omara-Otunnu (1992) at 462.

46 Oloka-Onyango J "'Decentralisation without human rights?' Local governance and access to justice in post-Movement Uganda" Human Rights and Peace Centre (HURIPEC) Working Paper (2007) at 12.

47 Museveni (2000) at 15.

48 Oloka-Onyango (2007) at 25.

49 Smith D Good governance and development (New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2007) at 113. [ Links ] See Art 12 (1) of the Constitution. See also "MPs oppose autonomy for minority tribes" The New Vision available at http://www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/13/699607 (accessed 30 October, 2009).

50 GOU Odoki Constitution Commission Report (Entebbe: Government Printer 1993) at 51. See also Uganda v Commissioner of Prisons Ex Parte Matovu 1966 EA 514. Mr Matovu, a chief in the Buganda Kingdom government, had mobilised his subjects not to pay taxes to the central government thereby challenging the legitimacy of the nation state.

51 Barro (1999) at 168.

52 Barro (1999) at 172.

53 Kanyeihamba (2002) at 71.

54 Odonga O Museveni's long march from guerrilla to statesman (Kampala: Fountain Publishers 1998) at 59. [ Links ] See Buczek A The paradox of US military aid: a case study of Uganda and the LRA: (Masters dissertation, International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague 2012), [ Links ] who characterises Uganda's ethnic identity questions as both "tribal" and "regional". Thus in terms of "tribal" identity, the Baganda, as the dominant ethnic subgroup, are juxtaposed to the rest of the ethnic groups in the country. The author further distinguishes the southern Uganda Bantu groups ("southerners") from the northern Uganda Nilotics groups ("northerners". See also Omara-Otunnu (1992) at 445.

55 See generally the Constitution (Amendment) Act 11 of 2005.

56 Oloka-Onyango (2007) at 24. The removal of Presidential term limits in 2005 essentially allowed President Museveni, in power since 1986, to seek another term or further terms in office after serving two constitutional terms from the time the 1995 Constitution was promulgated. In fact he had then served five terms since 1986. Rubongoya (2007) at 27-28 argues that by 2001 the NRM had suffered from regime survival, a phenomenon that replaced its historical legitimacy of purpose, and became internally more divisive and factionalised.

57 See the Constitution as amended, arts 69-71.

58 See the Constitution as amended, arts 74 (2).

59 See the Constitution, art 74 (1).

60 See generally the Constitution (Amendment) Act.

61 The Constitution of Uganda of 1995 art 71 (1) (a) provides:

"A political party in the multiparty political system shall conform to the following principles:

a () every political party shall have a national character;

b () membership of a political party shall not be based on sex, ethnicity, religion or other sectional division;

The Political Parties and Organisations Act, s 5 (4) provides:

"... a political party or organisation shall not be taken to be of a national character unless it has in its membership at least 50 representatives from each of at least two thirds of all districts of Uganda and from each region of Uganda".

62 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 3.

63 The Constitution art 72(2).

64 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 3 (1).

65 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 7 (5) (a).

66 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 21 (1) states:

"Where a political party or organisation does not comply with any of the provisions of this Act, the Electoral Commission may by (sic) writing require compliance; and if the political party or organisation persists in non-compliance, the Electoral Commission may apply to the High Court for an order winding up the political party or organisation".

The term "winding up" has its roots in company law and refers to the process whereby a company's legal existence is brought to an end.

67 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 21 (2) provides: "In any case, a political party or organisation convicted-

a () of an offence under section 14; or

b () of any other offence under this Act more than three times, The (sic) Electoral Commission shall apply to the High Court for an order to deregister the political party or organisation and the High Court shall make such orders as may be just for the disposition of the property, assets, rights and liabilities of the political party or organisation".

68 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 5 (a).

69 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 5 (b).

70 Political Parties and Organisations Act s 5 (3). Under the Penal Code Act, s 42A it is an offence to publicly express ethnically aligned sentiments.

71 Political Parties and Organisations Act ss 7 (5) (a), 21(1) and 21(2).

72 See Local Governments Act 1997 Cap 243 as amended.

73 Local Governments Act s 125(2).

74 Local Governments Act s 125(4).

75 See Uganda Electoral Commission, available at http://www.ec.or.ug/eresults.php. In May 1996, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni obtained 74.33%, Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere 23.61% and Muhammad Kibirige Mayanja 2.06%. There was a 72.9% voter turnout. In the 2001 March elections, Yoweri Kaguta Musevi obtained 69.33%, Kiiza Besigye 27.82%, Aggrey Owor 1.41%, Muhammad Kibirige Mayanja 1%, Francis Bwengye 0.31%, and Karuhanga Chapaa 0.14%. The voter turnout was 70.3%. Both the 1996 and 2011 elections were held under the One Party Political System. In 2006, a year after the introduction of political pluralism, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni (NRM) received 59.26%, Kiiza Besigye of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) 37.39%, John Ssebana Kizito of the (DP) 1.58%, Abed Bwanika (Independent) 0.95%, and Miria Obote (UPC) 0.82%. The voter turnout was 69.2%. In 2011, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni (NRM) received 68.38%, Kiiza Besigye (FDC) 26.01%, Norbert Mao (DP) 1.86%, Olala Otunu (UPC) 1.58%, Betty Kamya of the Uganda Federal Alliance (UFA) 0.66%, Abed Bwanika of the People's Development Party (PDP) 0.65%, Jaberi Bidandi Ssali of the People's Progressive Party (PPP) 0.44%, and Samuel Lubega (Independent) 0.41%. The voter turnout was 59.3%.

76 Lambright (2011) at 28.

77 See the GOU Uganda Electoral Commission, district council elections (Kampala: 2011). It is noted that some of the independent candidates lean towards the ruling party.

78 It is to be noted that before the centralisation of district senior managers in 2005, the Town Clerk was appointed by the Kampala City Service Commission. Although Kampala City is mainly cosmopolitan, it is dominated by the Baganda ethnic group. In fact the "deposed" Lord Mayor of Kampala City is a Muganda.

79 Article 5(4) of the Constitution. See also Constitution (Amendment) Act 2005. See further the KCCA, whose long title states:

"An Act to provide, in accordance with article 5 of the Constitution, for Kampala as the capital city of Uganda; to provide for the administration of Kampala by the Central Government; to provide for the territorial boundary of Kampala; to provide for the development of Kampala City; to establish the Kampala Capital City Authority as the governing body of the city ; to provide for the composition and election of members of the Authority; to provide for the removal of members from the Authority; to provide for the functions and powers of the Authority; to provide for the election and removal of the Lord Mayor and the Deputy Lord Mayor; to provide for the appointment, powers and functions of an executive director or and deputy executive director of the Authority; to provide for lower urban councils under the Authority; to provide for the devolution by the Authority of functions and services; to provide for a Metropolitan Physical Planning Authority for Kampala and the adjacent districts; to provide for the power of the Minister to veto decisions of the Authority in certain circumstances and for related matters".

80 Article 5(5) of the Constitution.

81 Article 5(46) of the Constitution.

82 Makara (2009) at 9.

83 Oloka-Onyango (2007) at 39.

84 See generally the 2011 Uganda Elections Results.

85 See Oloka-Onyango (2007) at 37 who argues: "The more telling reason was political; Kampala has for a long time been a hotbed of political opposition; by recentralizing control over its administration, it was hoped that the political problem could be handled. While no bill has yet been presented to Parliament, the draft which is circulating takes away the remaining vestiges of autonomy originally enjoyed by the Capital city and places it under the thumb of the President."

86 Kafeero D "Museveni tells off Lukwago in city tour" The Daily Monitor available at http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Museveni-tells-off-Lukwago-in-city-tour/-/688334/2284166/-/mtmwia/-/index (accessed 18 April 2014).

87 See Lukwago Elias & 3 others v the Attorney General and Another 2013 Miscellaneous Cause n°362 of 2013 Civil Division of the High Court of Uganda, see also Lukwago Elias and 3 Others v Attorney-General and another 2013 Miscellaneous Application No 445 of 2013 Civil Division of the High Court of Uganda, where the Judge stayed the Authority's councillors' meeting that purported to impeach the Lord Mayor. The alleged meeting was in fact chaired by the Minister of Kampala City Authority. The Court order was openly defied by the Minister, hence the extensive litigation on the matter.

88 GOU Report of the KCCA Tribunal, constituted to investigate allegations against the Lord Mayor of Kampala Capital City Authority pursuant to a petition of councillors of the Kampala Capital City Authority 2013 ().

89 Masereka "Drama as Lukwago is impeached" The Red Paper, available at http://www.redpepper.co.ug/lukwago-impeached (accessed 20 February 3014).

90 "Lukwago returns to court to fight tribunal report" The Observer available at http://www.observer.ug/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=29608:lukwago-returns-to-court-to-fight-tribunal-report&catid=34:news&Itemid=114 (accessed 9 April 2014).

91 Okanya A "Court to hear Lukwago petition on tribunal today" The New Vision, available at http://www.newvision.co.ug/mobile/Detail.aspx?NewsID=644110&CatID=1 (accessed 30 February 2014).

92 The sub judice rule is an old English common law rule that bars discussion of court cases before their determination. In Uganda this rule is still strictly enforced.

93 Oloka-Onyango (2007) at 11.

94 Makara (2009) at 64.

95 Lambright (2011) at 139-144.

96 Lambright (2011) at 140-141 (emphasis in original text).

97 See for instance, Tusasirwe B "Enforcing civil and political rights in a decentralized system of governance" Human Rights and Peace Centre (HURIPEC) Working Paper (2007) at 36 who discusses the voters' cynicism regarding the country's electoral process.

98 GOU Odoki Constitution Commission (1993) at 549.

99 The Constitution art 245(2)(e), on which basis the LGA, s 116(2) (3) and the Institution of Traditional or Cultural Leaders Act s 13(1) are enacted, bars traditional and cultural leaders from local government politics. The LGA s 116(2) (3) provides: "A person shall not be elected a local government councillor if that person... is a traditional or cultural leader as defined in article 246(6) of the Constitution." The Institution of Traditional or Cultural Leaders Act s 13 (a) (2) provide that any traditional or cultural leader that joins or participates in partisan politics must abdicate his position not less than 90 days before nomination day.

100 See Uganda Government (MOLG) Decentralisation: The Policy and its Philosophy. Kampala: Ministry of Local Government/Decentralization Secretariat (1993).

101 See generally GOU Decentralisation (2006); Singiza D & De Visser J 'Chewing more than one can swallow: the creation of new districts in Uganda (2011) 15 Law Democracy and Development 19-36.

102 The Daily Monitor 21 July 2009.

103 Singiza & De Visser (2011) at 23-24.

104 Omara-Otunnu (1992) at 463.

105 African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights ACHPR & ILO The overview report of the research project of the International labour Organisation and the African Commission of Human and Peoples' Rights on the constitutional and legislative protection of the rights of indigenous peoples in 24 African countries (Geneva: Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria 2009) at 45.

106 Singiza & De Visser (2011) at 27-27.

107 See GOU National population and housing census (2014).

108 GOU National population and housing census (2014).

109 GOU National population and housing census (2014).

110 GOU National population and housing census (2014).

111 GOU National population and housing census (2014).

112 Telephone interview with Mr. Amos Isimbwa of the Minority Rights Group International, Basongora community representative (Uganda) on 19 August 2013.

113 Kanyeihamba (2002) at 1; Museveni (2000) at 34-35.

114 Giles H, Coupland J & Coupland N "Accommodation theory: communication, context, and consequence" In Howard G, Coupland J & Coupland N Contexts of accommodation (New York: Cambridge University Press 1991) at 418-419. [ Links ]

115 Howard-Hassmann R "The full-belly thesis: should economic rights take priority over civil and political rights? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa" (1983) 5 HRQ 467. [ Links ]

116 Gwartney J & Wagner R "Public choice and constitutional order" in Bayart J-F (ed) The state in Africa: the politics of the belly (London: Longman Group (United Kingdom) 1993) at 41-59. [ Links ]

117 Erk J & Anderson LM et al (eds) The paradox of federalism: does self-rule accommodate or exacerbate ethnic divisions? (New York: Routledge 2010) at 37. [ Links ]

118 Smith (2007) at 113.

119 Siegle & O'Mahony (2006) at 49.

120 Siegle & O'Mahony (2006) at 49; Stauffer T & Topperwien N "Federalism, federal states and decentralization" in Stauffer T, Fleiner L & Topperwien N (eds) Federalism and multiethnic states: the case of Switzerland (Basel, Geneva, Munich: Helbing &Lichtenhahn (2000) at 48. [ Links ]

121 Lambright (2011) at 89.

122 Lambright (2011) at 89.

123 Muzaale F 'Museveni surrenders land disputes in Kayunga to law' The Daily Monitor available at http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Museveni-surrenders-land-disputes-in-Kayunga-to-law/-/688334/2051368/-/nrc9h0/-/index.html (accessed 30 November 2013).