Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.19 Cape Town 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/LDD.V19I1.2

Kenya's implementation of the Smuggling Protocol in response to the irregular movement of migrants from Ethiopia and Somalia

Noela BarasaI; Lovell FernandezII

INational Project Manager, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office in Eastern Africa

IIProfessor of Law and Co-director of the South African-German Centre for Transnational Criminal Justice, UWC

1 INTRODUCTION

The Horn of Africa continues to be engulfed in a crisis. Political transitions have taken place in the East and the Horn of Africa sub-region in the recent past. Human rights violations continue to occur in Somalia, Eritrea, South Sudan and Sudan. The above-mentioned regions are fraught with tension and are home to recurring cycles of conflict, primarily due to conflicting geopolitical and economic interests, as well as environmental factors that have led to frequent droughts and prolonged spells of famine.

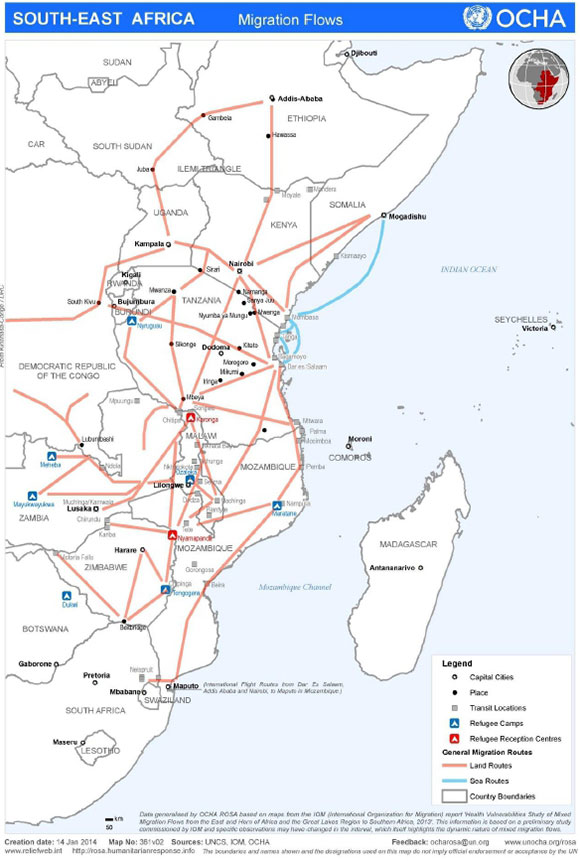

The southward movement of migrants from Ethiopia and Somalia to Kenya, as a transit or destination country, has assumed a multi-layered and multi-causal dimension over the last 20 years. Migrants who are part of this movement often have South Africa in mind as their final destination. The movement has evolved from one involving refugees and asylum seekers to one which, in the 21st century, has been typified as mixed migration. Mixed movements (flows) are, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), "[c]omplex migratory population movements that include refugees, asylum-seekers, economic migrants and other migrants, as opposed to migratory population movements that consist entirely of one category of migrants."1

The movement of Somalis and Ethiopians commenced in the mid-20th century, and was exacerbated by the fall of the Mengistu rule in Ethiopia, and the Siad Barre regime in Somalia, in 1991.2 Influxes are dependent on the prevailing social, political, and climatic conditions in the regions of Somalia and Ethiopia. In Somalia, the early 1990s were characterised by displacement as a result of civil war. In 1991, the fall of the Siad Barre regime resulted in anarchy and violence. Somalis began to troop to Kenya during this period when key resources were controlled by warlords.

In 1992 the registered Somali refugee population in Kenya had risen to 285 000, and by January 2015 it had reached 462 970,3 an increase attributed to insecurity and an acute drought in the Horn of Africa. In 2007 the border between Kenya and Somalia was officially closed.4 However, the 682 km of border is open and porous, allowing the undetected entry and exit of migrants.5 Reports abound of harassment by Kenyan police, extortion, arbitrary arrests and the detention of Somali asylum seekers, refugees and Ethiopian migrants.6 The migrants are arrested, detained and charged with being unlawfully present in Kenya. They are dealt with in summary criminal proceedings which involve a plea of guilty, punishable by a year's imprisonment in lieu of a fine and/or a repatriation order.

In Khali Abdiaziz Mohammud and Three Others v Republic,7the appellants had been charged with being unlawfully present in Kenya, in violation of section 13(2)(c) of the Immigration Act8, which has since been repealed. The Senior Resident Trial Magistrate rejected the pleas in mitigation and instead highlighted the fact that by unlawfully crossing the Kenyan border with Somalia at a time when the border was closed, the appellants had breached Kenyan peace, security and sovereignty and had posed a danger to Kenya. They were sentenced to serve one year in prison, after which they were to be repatriated. On appeal to the High Court of Kenya in Nairobi, the trial court judgment was set aside and the sentence was reduced to a fine of about US$ 135 or two months' imprisonment, but the repatriation order was upheld. The High Court, per Ojwang J, set aside the trial court judgment on the basis that the magistrate had erred in law and fact by failing to take account of the pleas in mitigation submitted by the appellants and the fact that they were first offenders. The court was highly critical of the harsh punishments imposed, pointing out that "that there is now a trenchant body of jurisprudence on sentencing, which carries a policy discouraging overkill in the imposition of prison terms, where the outcome of a prison term, far from inuring to the benefit of Kenya and Kenyans, merely dispenses vengeful penalty against aliens."9

However, in practice, a vicious cycle of recidivism ensues, with migrants re-attempting the journey after being deported.10 The use of smugglers decreases the risk of detection by police, but unofficial routes utilised consist of hazardous vast terrain and vast wildernesses, rendering the migrant susceptible to the whims of the smuggler.11Smugglers rarely take into consideration the basic survival necessities of migrants, such as, food, water and shelter, during the journey. In addition, smugglers may abuse the migrants physically, or abandon them in the course of the journey out of fear of being detected. The smuggling enterprise consists of a chain of people accountable to a boss, the chief smuggler. The latter, who is a key actor in the irregular movement of people, is often well-known to the community, the smuggled migrant, and/or the financier of the transaction. He is also known to the authorities, but nothing is done to bring him to book.12 This inaction is attributable to the allegedly corrupt public officials who collude with the smugglers in the smuggling enterprise. Moreover, the plight of the smuggled people is aggravated by the immigration officials' insistence on using the criminal justice process as a way of dealing with the smuggled migrants, while the profiteers and facilitators are left off the hook. Although difficult to estimate in scale, migrant smuggling has grown into a multimillion dollar enterprise, involving transnational organized criminal elements. It is against this background that the discussion now turns to the 2004 United Nations Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, commonly referred to as the Smuggling Protocol, which supplements the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC).

The international legal framework requires (a) the decriminalisation of the smuggled migrant, whose movement is facilitated by an organised criminal group; and (b) the criminalisation of facilitators and profiteers of the movement. The smuggling of migrants points to several phenomena, namely, the existence of criminal elements within the community; corruption among State officials and their complicity with other State and non-State actors; irregular movement of people; and the exploitation of a desperate population of migrants from the countries of origin.13

This article assesses Kenya's progress in the implementation of the Smuggling Protocol in relation to the influx of irregular migrants from Somalia and Ethiopia. It analyses some of the features of organised crime and the revised immigration law that was enacted after Kenya adopted a new constitution in 2010. The article also explores the deleterious effects of the smuggling of migrants on both the countries of origin and destination. Finally, it recommends measures to increase the protection of the growing number of migrants willing to make the hazardous journey south, from Ethiopia and Somalia.

2 TERMINOLOGY AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 2.1 Smuggling of migrants

The IOM has defined the smuggling of migrants as "the intentional organization or facilitation of the movement of persons across international borders, in violation of laws or regulations, for the purpose of financial or other gain to the smuggler". The internationally recognised definition is contained in Article 3(a) of the Smuggling Protocol, while illegal entry is defined in Article 3 (b). The definition raises two questions: First, who are the parties involved in the smuggling process? Secondly, can a person subjected to smuggling be described as a victim of a crime, or would it be more accurate to label such a person as a criminal?

A smuggler who is directly or indirectly involved in the smuggling of migrants is "an intermediary who moves a person by agreement with that person, in order to transport him/her in an unauthorized manner across an internationally recognized state border."14 The person aided by the smuggler to enter a country illegally is a smuggled migrant.15 Hazardous living conditions caused by unemployment and poverty, let alone natural disasters and wars, have resulted in an increased demand for the affected people to migrate. This heightened demand for migration far outstrips the number of ways in which people can cross international borders legally.16 The smuggler responds to the increased demand for migration by exploiting the vulnerabilities and precarious situation of migrants for profit.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) states that "a smuggled migrant is not considered to be a 'victim of migrant-smuggling', because, generally, a person consents to being smuggled."17 However, smuggled migrants have given horrific accounts of their ordeals during the smuggling process. They have complained about being crammed into small, windowless spaces, sometimes filled with faeces and vomit, deprived of food and water, and of having witnessed the corpses of their deceased companions being discarded into the sea or left in the wilds. Some have described how they have been assaulted physically and subjected to psychological abuse. In this regard, smuggled migrants can become victims of crime as a result of the smuggling process, and in some instances have been exploited by human traffickers.18

Ironically, smugglers operating in Ethiopia and Somalia invariably call themselves "travel agents" and do not necessarily consider their activities to be criminal. They view themselves as providers of a humanitarian service, assisting persecuted populations to escape to safety. Similarly, smuggled migrants do not view themselves as victims of a crime, despite the abuse they experience during, and as a result of, the smuggling process. Migrant smuggling has been described as a complex, ever-changing crime committed by various forms of criminal networks that are difficult to combat.19

2.2 Smuggling of migrants versus trafficking in persons

Smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons are distinct concepts although they overlap significantly. In some instances, what begins as a case of migrant smuggling ends with the smuggled migrant becoming a victim of trafficking. In practice, it has been difficult to distinguish between the two concepts. Trafficking in persons is defined comprehensively in Article 3(a) of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (Trafficking Protocol).20 The definition can be examined through its three constituent elements: the activity, the means and the purpose.

The activity involves the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a person. The means include the use of force, threat of force or coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power, abuse of a position of vulnerability, or giving or receiving of payments. The means used negate any consent that may have been given to the activity.21 The purpose is always exploitation, the various forms of which Article 3 (a) lists as including the exploitation of the prostitution of others, other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs. All three constituent elements must be present for the offence of trafficking to be committed.

For example, a young woman from Ethiopia is deceived about an employment opportunity at a hotel in Nairobi. When she arrives in the city she is directed to a household of ten where she works 18 hours a day as a domestic worker, with little or no pay. When she complains about her working conditions, she is threatened with arrest and deportation for being in the country illegally. In this scenario, all the constituent elements of trafficking in persons have been fulfilled. The young lady was recruited through deception and subjected to servitude. Furthermore, her co-operation is ensured through threats. The three elements constitute the actus reus of the offence.

The means mentioned above do not have to be proven where the victim of trafficking is a child.22 It suffices to prove that the activity took place for the purpose of exploitation. Trafficking in persons may be established as a strict liability offence. In jurisdictions that require mens rea as the subjective element of the offence, it must be proved that the perpetrator committed the material act with the intention to exploit the victim, and with knowledge of the unlawfulness of the conduct.23 The actual exploitation does not need to take place; it is sufficient to demonstrate that exploitation was intended.

2.3 Similarities and differences between smuggling and trafficking

Criminals may traffic and smuggle persons in the same movement, utilising similar routes and transportation methods.24 Smuggled migrants willingly submit themselves to the smuggling process. Trafficked victims, on the other hand, do not consent to being trafficked, and if they do, their consent is rendered meaningless by the deception of the trafficker. The key differences between smuggling and trafficking as described by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime are elaborated below.

2.3.1 Smuggling as a trans-national crime

The smuggling of migrants must involve an element of trans-national movement. The migrant must cross a legally recognised border in violation of the destination country's requirements for admission. The offence of trafficking, on the other hand, does not necessarily entail a transnational element; it is concerned with the intended exploitation of the victim.25Victims of trafficking may be bought from, and sold to, different traffickers and moved within the country or from one country to another through regular or irregular means.26

2.3.2 Consent

The trafficked migrant does not consent to the trafficking process and where he or she does, such consent is vitiated by the means set out in Article 3 (b) of the Trafficking Protocol. The smuggled migrant, on the other hand, actively seeks out the smuggler, and pays for his services to facilitate the irregular movement to the desired country of destination. The hazardous conditions that smuggled migrants face in some instances may, however, cause them to withdraw their consent during the journey.

2.3.3. Exploitation

The human trafficker and smuggler both engage in the illegal conduct for profit. The smuggler and the migrant enter into an agreement that ends upon illegal entry or crossing into the destination country. The consideration is a sum agreed upon by both parties, and the contractual relationship ends with the illegal entry into the country of destination. In contrast, the trafficker deceives his victims with the intention to exploit them. The victim does not consent to the intended exploitation and the relationship between the two parties may persist long after the beginning of the trafficking process. In practice, a smuggled migrant may end up a victim of trafficking, and this happens where the smuggler or a third party exploits the smuggled person's irregular status or vulnerable position for benefit.

2.4 Irregular migration

There is no clearly accepted universal definition of irregular migration. The IOM defines it as "movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries".27 Both human trafficking and smuggling occur within the rubric of irregular migration. An irregular migrant is "a person who, owing to unauthorized entry, breach of a condition of entry, or the expiry of his or her visa, lacks legal status in a transit or host country".28

2.5 Mixed migration

The IOM defines mixed flows as "complex migratory population movements that include refugees, asylum-seekers, economic migrants and other migrants, as opposed to migratory population movements that consist entirely of one category of migrants".29The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) describes mixed migration as "people travelling in an irregular manner along similar routes, using similar means of travel but for different reasons".30 Victims of trafficking are sometimes part of this movement. Human smuggling is at the centre of mixed migration movements and is aided by corruption during the border crossing process.31 The challenge in dealing with mixed migration movements is to identify migrants with a legitimate claim to asylum and to provide appropriate assistance to other migrants who are similarly vulnerable but fall outside the purview of refugee protection.

2.6 Refugees and asylum seekers

A refugee is defined in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.32 An asylum seeker is a person who is awaiting status determination for refugee protection. Towards the end of the 20th century the movement of refugees and asylum seekers has been characterised as forced migration. The IOM defines forced migration as "a migratory movement in which a level of coercion exists, including threats to life and livelihood whether arising from natural or manmade causes."33 Forced migrants include groups that do not fit within the legally defined limits of a refugee, such as, people displaced by natural disasters and those who have not yet crossed an internationally recognised border.

2.7 Organised crime and transnational organised crime

Organised crime has so far eluded a universally accepted definition. Article 2(a) of the UNTOC defines an organized criminal group as a "structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with this Convention, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit". The UNTOC definition, like the one proposed by Interpol and the European Commission, does not consider the loosely structured and fluid nature of most organised crime syndicates. Smuggling networks in East Africa, for example, have loose formations which constantly change, depending on the desired criminal objective.

3 HISTORY OF THE SOUTHWARD MOVEMENT OF SOMALIS AND ETHIOPIANS

Since the 1970s, the Horn of Africa, which comprises Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Sudan, has been known internationally as a region whence refugees emanate. Involuntary movements have been attributed to political, economic and environmental factors. In some instances, governments have also been accused of manipulating irregular population movements to achieve selfish political gains.

3.1 Somalia

In 1967, the last democratic election held in the Republic of Somalia resulted in the formation of a de facto one-party state. Public dissatisfaction with the unfolding events led to the assassination of President Abdirashid Shermake and the staging of a bloodless coup in 1969. Siad Bare, previously commander of the army, became the President. The state took on a socialist orientation, and in 1977, following a renewed attempt at Pan-Somalism, Somalia attacked Ethiopia. The conflict, in which Somalia was defeated, spawned the first movement of Ogaden refugees fleeing from Ethiopia to Somalia.34

Clan polarisation, endemic war, famine, starvation, and growing inequality in contravention of the Somali egalitarian ideal led to the collapse of the state in January 1991. An estimated one million Somalis moved to surrounding countries and overseas destinations. Mohamed Farah Aided, who took over from the military coup of Siad Barre, died in Mogadishu in 1996, succumbing to wounds sustained during fighting in the capital.

Today, the anarchy and polarisation that have characterised the post-independent state of Somalia more or less persists, making Somalia the second most fragile state in the world.35 Numerous attempts have been made to re-establish social and political cohesion. A failed United Nations peacekeeping mission, backed by United States marines, was withdrawn in 1995. A fourteenth attempt to establish a central system of government resulted in the election of Abdullahi Yusuf as President in 2004. Yusuf's government was inaugurated in Kenya.

The transitional government met for the first time in Baidoa, Somalia, in 2006. Successive years were characterised by heavy fighting between the transitional government and Islamists, wrestling for control of Mogadishu. This state of affairs was aggravated by periodic spells of severe drought, resulting in a deepening humanitarian crisis. In 2011 alone, 164 375 Somalis fled to Kenya and 101 333 to Ethiopia.36 Some countries deported them back to Somalia despite the risks they would face.37 An African peace keeping mission, backed by the United Nations, arrived in Mogadishu in December 2007. At the end of 2008, President Yusuf resigned, following a vote of no confidence in his government, and he was replaced by the moderate Sheikh Sharif, who was elected by Parliament.

Towards the end of 2011, and going into 2012, an African Union army supported the government's forces to wrestle major cities from the al Qaeda linked Islamist group, al Shabaab. In August 2012, the first parliament in more than 20 years was sworn in in Mogadishu, and Hassan Sheik Mahmoud was elected President. This was the first democratically elected government in Somalia since 1967.38

The Somali community is primarily pastoralist in nature, with an agriculturally based economy. Migration is prevalent within the community in search for work and study opportunities in neighbouring countries and further afield. This has been the case since the 1920s, however, recent movement has been attributed to the poor state of human security. The fall of the Siad Barre regime, followed by the humanitarian crisis caused by the civil war and famine during the repressive years of warlord Farah Mohamed Aideed's guerrilla insurgency, resulted in the mass movement of people from Somalia. The more affluent Somalis moved to North America, Europe and the Gulf States, with the lesser privileged going to Kenya and surrounding countries in East Africa.39 Conflict, poverty, drought, and food security have escalated the movement in recent years.

3.2 Ethiopia

Ethiopia, with a population of 90 million, is the second most populous country in Sub-Saharan Africa.40 Over the last decade the country has experienced strong economic growth, averaging 10.9 per cent per year from 2005 to 2013.41 The economic boom has helped to alleviate the incidence of poverty and has contributed to making it possible for Ethiopia to achieve significant progress towards reaching the Millennium Development Goals with regard to reducing child mortality, achieving gender equality, combatting HIV/AIDS and malaria, and aspiring towards universal primary education.42However, the World Bank still ranks Ethiopia as one of the poorest countries in the world, with between 20 and 30 per cent of the population living in extreme poverty.43The urban unemployment rate is estimated at 17, 5 per cent.44

Ethiopia was traditionally ruled by emperors until the fall of Haile Selassie in 1974. The country then came under the socialist rule of the Derg regime. During this time civil liberties were repressed and movement outside Ethiopia was restricted. The regime, subsequently led by Haile Miriam Mengistu, was overthrown in 1991 by a coalition consisting of different ethnic groups, the Ethiopians People Liberation Front (EPLF). The flow of Ethiopians in earnest started in 1991 but has increased in recent years.45

Between 1991 and 2000 Ethiopia separated from Eritrea, adopted a constitution, conducted the country's first elections and signed a peace agreement with Eritrea to end a bitter conflict.46 The country also suffered catastrophic famines in the mid-1970s through to the 1980s. In earlier times, migration was primarily dictated by political persecution and conflict. Recently, economic reasons have dictated the movement.47Amongst the rural youth, migration is driven by the desire for education, which opens new opportunities for personal betterment elsewhere, beyond the rural areas.48 Studies have shown that Ethiopian migrants typically spend one to three years in a neighbouring country, such as Kenya, before migrating west.49 The growth of an economically active population, coupled with conflict, environmental degradation, and economic decline, have increased labour and forced migration from Ethiopia to countries within the East African Region and beyond.

4 SITUATION OF SMUGGLED MIGRANTS IN KENYA

Kenya hosts the largest population of Somali refugees, and is a well-documented regional hub for the smuggling of migrants and acquisition of false documentation.50Prison facilities in Moyale, Isiolo and Marsabit are reportedly overcrowded because of the large number of migrant arrests. Refugee protection and assistance is co-ordinated jointly by the UNHCR and the Kenya Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA).

Until recently, migrant smuggling within the organised crime context had not been defined by Kenyan law. In 2011, the Kenya Citizenship Act was enacted and it mirrors the definition in the Smuggling Protocol. Policy makers, civil society and the media often refer to the smuggling and trafficking of migrants interchangeably, failing to recognise the mutual exclusivity of the terms. In practice, however, a clear dichotomy between the two terms is easily blurred, with smuggling scenarios exhibiting elements of trafficking and vice-versa. The exact number of persons smuggled from Somalia and Ethiopia into Kenya is unknown due to the clandestine nature of the movement. A provincial police officer in Kenya's Mombasa county estimates that about 140 trafficked people or smuggled migrants are arrested every week, which brings the annual total to about 7 280 arrests.51 An immigration officer reported that between 70 and 100 irregular migrants are deported every month.52 The Kenyan media frequently report on stranded Ethiopians in remote areas, or those harboured in various locations in Nairobi. Migrants who have served their sentences for being unlawfully present in Kenya are not deported immediately, but may continue to languish in Kenyan prisons for some time awaiting repatriation assistance.53 The paucity of data makes it difficult to estimate the number of people smuggled, which number would ordinarily be taken into consideration in crafting an appropriate response.

4.1 Smuggling of migrants within the organised crime context in East Africa

Smuggling networks in the Horn and East Africa have an informal structure. An IOM report on the movement of migrants from Somalia and Ethiopia to Kenya and further south has compared the facilitators' modus operandi to that of courier service providers, with slight variations.54 The networks consist of opportunistic individuals, in contrast to the hierarchical structure of large organised crime syndicates operating in the West.

Taxi, bus, and lorry drivers, as well as bush guides and those who enter into contracts with and accompany migrants on irregular crossings, are all considered smugglers because they derive benefit from the movement. The typical smuggler is an 18- to 40-year-old male of Ethiopian or Somali origin.55 An Ethiopian woman based outside Nairobi, and known by immigration officials, has also gained notoriety for being part of the smuggling ring.56

The IOM study found that the linchpin managers in the smuggling chain are Somalis who are situated in major East African cities and at key transit points, such as, ports, refugee camps or border areas. The managers work with the chief smugglers. Typically, they sub-contract transportation, bush guide or facilitator services to local pools of opportunistic criminals. The smuggling managers, who are stationed along the smuggling route, play a key role in the smuggling chain and are paid by the chief smuggler, who is the principal linchpin, to move a group of people from one point to another. The chief smuggler is not necessarily based in the same city.

The managers are very flexible. They work independently, and offer their services to local and chief smugglers across the border. Somali smugglers generally work with fellow clansmen throughout the network, and four Ethiopian brothers were identified as having spread themselves out along the southern route, defending each other's interests and ensuring control of their network.57 Immigration and police officers interviewed in IOM's study revealed that the smuggling manager's mobile phone is his main tool of trade, as it contains a list of local transporters, compromised government officials, managers and chief smugglers in other locations.

The IOM study compared the human smuggling model in East Africa with the one in Mexico, which has been described as the "supermarket" model. Comparatively speaking, both models are relatively low cost, have high failure rates at border crossings, are characterised by repeated attempts, are run by multiple actors who act independently or are loosely affiliated to one another, and do not have a strong hierarchy or a violent organisational discipline. Their business is based on the capitalistic ideal of maximising profit, and they compete fiercely with each other.

The smugglers are aware that they are operating unlawfully, and in most instances are willing to face the consequences. Where a bribe does not suffice, they will most likely pay a modest fine or face deportation. Smuggled migrants are driven to Nairobi in lorries fitted with fake bottoms, and they pay between US$600 and US$700 for the transportation of two undocumented migrants to Nairobi.58 A self-confessed Somali smuggler interviewed at a prison in Mombasa said that Somalis are always on the run to safety, with Kenya being one of their primary destinations.59 He said that he charges US$120 per migrant smuggled and carries up to 120 migrants per trip when business is booming. The smuggler owns a boat that brings migrants to the shores of Kenya's Mombasa County.

The large Ethiopian and Somali diaspora pay a large portion of the smuggling expenses through the hawala system. Hawala is an informal, parallel, international money transfer system based on trust. A simple scenario involves A in London contacting a hawala dealer (called a hawaladar) X to transfer money to his cousin B in Mogadishu. X receives the money to be transferred to B and contacts Y, another hawaladar in Mogadishu to give the money to B. B may have to provide a password before the money is released to him by Y. Transmitted funds do not necessarily cross international borders physically. X and Y may be in business together or linked via a wider network and they will not keep individual transaction records but rather their records will reflect the balances of what is owed between the hawaladars. The advantage of the hawala transfer system is that the recipient does not have to prove his identity by showing an identity document, which many rural communities across the Horn of Africa lack. The sender remains anonymous, which is beneficial for both those who overstay their visa time limits, and people in irregular situations, such as irregular immigrants in search of employment. The hawala system is fast and cheap, involving no more than a telephone call between hawala dealers. Furthermore, transfers to recipients take place in urban vicinities as well as in the remotest, rural locations. Hawala does not leave a paper trail connecting smugglers to the criminal enterprise.

Nairobi is a key location for the receipt of smuggling fees and is the Kenyan headquarters of the hawala system.60 The Somalis are financed predominantly by the diaspora, while a significant number of Ethiopians are funded with the proceeds from the sale of private family assets. Characteristic among both communities is that the decision to leave home is taken collectively, because it is viewed as an economic investment by relatives and clan members.61 Mobile cash transfers are effected through the Western Union money transfer system and through Mpesa, a mobile phone cash transfer system popularly used in the East African region.

4.2 Modalities of the movement

Migrant smuggling from Ethiopia and Somalia generally occurs as mixed migration movements. The migrants within these movements comprise refugees, asylum seekers, economic migrants, unaccompanied and separated children, and in some instances, victims of trafficking. While some of the migrants are destined for Kenya, many of them use Kenya as a rest stop while their documents are processed and arrangements are made to re-finance their onward journey.62 Smuggled migrants from Addis Ababa in Ethiopia are in contact with major smuggling organisers in Nairobi.63 Research and press reports have noted that most of the migrants have South Africa in mind as their final destination.

The movement is organised by smugglers in violation of the laws of both transit and destination countries. Young, rural, Ethiopian men are actively targeted by smugglers, who entice them with a better life elsewhere.64 The smugglers themselves are efficient, as Long and Crisp point out: "Smugglers run well-organized, dynamic operations that involve a constantly changing network of collaborators, including recruitment agents, truck drivers and transporters, boat owners, providers of forged and stolen documents, border guards, immigration and refugee officials, members of the police and military".65

Up to 50 Somali smuggling groups are estimated to control the irregular migratory route to Southern Africa.66 Alleged corrupt and complicit public officials appear to be driving the smuggling of migrants, exacerbating the situation.67 Public officials, particularly in the North Eastern Province of Kenya bordering Somalia, have been implicated in corruption as a result of the intermediary role they play between government offices and migrants in transit.68 A Kenyan police officer interviewed for the IOM study stated that the extent of public officials' collusion with smugglers implies that they play an integral part in the illegal and abusive enterprise.69 On the Somali side of the Kenya-Somali border, at Dobley, a network of smugglers offers young men a more attractive option than the Daadab refugee camp.70

Most Somalis do not have a recognised valid passport to facilitate regular travel. Instead, they travel by boat from Mogadishu and Kismayo to Mombasa, Kenya.71 Vessels from Kismayo bring dried fish and human cargo to the old ports in Mombasa, Kilifi and Lamu, and to the unregulated ports along the north coast. Migrants are transported in small, overloaded boats exposed to the elements. To travel from Mombasa, they often wait long periods for promised transport or a guide. Some are transported to Shimoni, from where they are transported to Tanzania by boat, en-route to South Africa. Bribes smooth things over with the authorities at Shimoni. Immigration officers claim they are ill-equipped to intercept the movement along the 110km coastline from Likoni to Vanga, which has an estimated 176 illegal entry points.

Brokers assist in the smuggling of Somalis directly from Mogadishu to Nairobi, or via Nairobi to South Africa. They enter Kenya by four-wheel drive vehicles or lorry, via Dhobley, close to Kenya's Liboi border with Somalia. The migrants who opt for this passage have a legitimate claim to asylum. They are granted prima facie refugee status in Kenya, and use the services of smugglers as the only means of obtaining protection. Mass movements resulting from generalised violence diminish the capabilities of authorities to conduct individualised refugee status determination processes. As a result, and because of valid reasons for fleeing, mass population displacements may be granted prima facie status by host governments. The largest community of Somalis in Kenya, after Dadaab refugee camp, resides in Eastleigh, in Nairobi, which has an unsurprisingly large network of smugglers and their agents.

Despite the existence of a bilateral agreement between Kenya and Ethiopia in terms of which the citizens of each country have freedom of movement and the right to carry on trade in the territory of the other, Ethiopians travelling by bus, truck, or on foot, are required to pay bribes to Moyale border immigration officers through brokers, regardless of the status of their documentation.72 The bribe is between US$250 and US$450 for a travel stamp. The profits from this activity are shared among government officials in Moyale and with the provincial headquarters in Garissa. There are Ethiopian migrants who travel through the bush to avoid paying the corrupt passage fee. On being intercepted, they are heavily extorted. Smuggled migrants are also required to pay bribes at road blocks on the journey to Nairobi.

Ethiopians travel from Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, by road, through the Moyale border in Kenya, to Nairobi, and may proceed to the Mombasa or Namanga borders with Tanzania for their onward journey south. Moyale is a major nexus for smuggling and 60 per cent of the town's income is said to be derived from the business. As noted in the East Africa Standard:

Ethiopians get into Kenya through Moyale, Dukana and Forolle in North Horr, Bute in Wajir North and Takaba in Mandera West. However, most of them connect to Isiolo from Moyale using cattle trucks passing through Merti to avoid arrest. This is a big business and it is very difficult to fight the cartels, some that operate in Ethiopia and South Africa. But we are liaising with the Immigration Department to see how we can beat them.73

In December 2010, the town of Isiolo recorded more than 300 arrests of Ethiopian and Somali migrants. Stricter surveillance in Garissa has made smugglers turn to the Isiolo route to prevent detection.

Mandera, the farthest corner in North Eastern Kenya, is a gateway for many Somalis coming through Kenya. Similar accounts of bribery, extortion and complicity of public officials in the smuggling of migrants through Mandera abound. A tribal chief interviewed in the IOM study confirmed that human trafficking is a big business in Mandera, to the extent that its interception could trigger a clan war.74 Persistent terrorist attacks in the Northern frontier in the last couple of years have, however, increased surveillance and security in those regions as well as corrupt practices. In addition, the Kenya Defence Forces have been deployed to border areas to reinforce security.

4.3 Linking the causal factors to the movement

The most obvious reason for Somalis leaving their country is violence brought about by the political situation. In 2011, increased fighting between government forces and two Islamist groups, Hisbul Islam and al Shabaab, coupled with a crippling drought situation, gave rise to an unprecedented movement of Somalis from the south and central region into Kenya and surrounding countries.

Somalis also move to escape personal persecution as a result of their political affiliation, clan membership and gender. Their departure is also prompted by their desire to evade forced conscription, and the search for basic commodities such as, food, medical services, healthcare and more viable livelihoods.75 The 2009 research report commissioned by the IOM revealed that war and insecurity was the number one reason for the exodus from Somalia, followed by unemployment and poverty.76 The situation in 2015 remains largely unchanged.

Even though Ethiopia has not experienced Somalia's level of violence, political oppression and economic stagnation have impelled a mass exodus from the southern part of the country. The Oromo people in the south and south east of the country have felt the unwelcome winds of political oppression and economic marginalisation, driving them to leave the country.77 Avoiding recruitment, and desertion from the army have also pressed many young men to leave Ethiopia.

However, at the centre of these departures remains the search for a better life, spurred by the perceived prosperity of neighbours whose sons have already moved away.78 In the IOM report, over half of the respondents stated that they had left their homes because of unemployment.79 Respondents also cited the pursuit of greener pastures due to poverty, insecurity and war.

4.4 Deleterious effects on the countries of origin and destination

Migrant smuggling indicates the existence of corrupt networks consisting of government officials and private citizens involved in bribery and extortion. The issue is much more broadly linked to issues of good governance, state transparency and accountability.80 Migrant smuggling is a profitable, illicit business whose proceeds are untaxed and may be used to fund other criminal activities. The hawala system has been found to be used to transmit most of the illicit proceeds from smuggling activities, thus ensuring that there is no paper trail. Hundreds of migrants continue to die of suffocation and other abuses during the perilous journey. The youth, a valuable human resource for any country, are being wasted in the case of Somalia and Ethiopia. Recently, irregular movement within the Horn of Africa and the surrounding region has sparked renewed fears that terrorist elements are taking advantage of a lax border security environment to launch deadly attacks in Kenya and promote an extremist ideology among the youth.

4.5 East Africa's and Horn of Africa's response to the smuggling of migrants

The East African Community (EAC) Common Market Protocol signed by the respective countries' heads of state entered into force on 1 July 2010. This Protocol envisages free movement among citizens in the East African region. The EAC is exploring prospects of South Sudan joining the Community, and Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia and Somalia have recently also expressed their interest in joining it. Integrating a displacement framework into the EAC free movement regime may contribute to enhancing migration management in the region.

The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Regional Consultative Process (RCP) on Migration held its first meeting in 2010 and subsequent meetings in 2012 and 2013 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The IGAD-RCP was established in 2009 to facilitate regional dialogue on migration issues among IGAD Member States, and seeks to promote the 2006 African Union (AU) Migration Policy Framework. The Framework provides policy guidance on various thematic issues including irregular migration, forced displacement and the human rights of migrants. Both Ethiopia and Somalia are IGAD Member States and part of the RCP.

In 2010 a Regional Conference on the theme Refugee Protection and International Migration: Mixed Movements and Irregular Migration from the East and Horn of Africa to Southern Africa, was held to encourage constructive discussion among states and other stakeholders on the problem regarding the mixed movement of people southwards. Participants from Ethiopia and Somalia were among the attendees. The conference discussed migrants' rights, enhanced legal migration alternatives and border migration. An action plan was adopted, addressing legislation, capacity building, outreach, cooperation, data collection and operations. A Joint Commission Meeting for Technical Co-operation between Kenya and Tanzania agreed to enhance co-operation to control smugglers and to curb irregular migration.81

The IOM has also established a Regional Committee on Mixed Migration for the Horn of Africa and Yemen to facilitate the co-ordination of government actions in addressing cross-border movements. The Committee held its fourth meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, at the end of October 2014. Representatives from Somalia and Kenya were present. There may be a need to consolidate the above initiatives into a coherent regional policy, guided by the AU Migration Policy Framework, towards enhanced efficacy in addressing irregular movement, and enhancing protection for migrants in the Horn of Africa and surrounding region.

5 INTERNATIONAL LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK ON MIGRANT SMUGGLING

A legislative response to the smuggling of migrants should encompass prevention, protection, prosecution and co-operation, all of which will be discussed below. Such a response needs to be guided by human rights standards as well as by refugee and humanitarian law. The primary international legal instruments and customary law principles propagating these tenets are discussed below insofar as they relate to the treatment of smuggled migrants.

The Smuggling Protocol, which supplements the UNTOC, aims to decriminalise the smuggled migrant and to criminalise the financiers and profiteers of the smuggling process. The UNTOC, on the other hand, broadly addresses trafficking of women and children, the smuggling of migrants, and the manufacture of, and traffic, in illicit firearms.82 The UNTOC seeks to promote co-operation and prevention, and to combat transnational organised crime. 83 These objectives are aimed at addressing conduct criminalised pursuant to its Article 3. The criminalised conduct includes: participation in an organised criminal group; laundering of the proceeds of crime; corruption; obstruction of justice; and serious crime. Article 2 of the UNTOC defines a serious crime as an offence which carries a penalty of four or more years' imprisonment. The criminalised conduct must be of a transnational nature, and must involve an organised criminal group.84 The criminalised conduct under the UNTOC is implicit in the smuggling of migrants.

The Smuggling Protocol should be read together with the UNTOC.85 In this regard, ratification of the Protocol is conditional upon the accession of a state party to the UNTOC.86 The Smuggling Protocol was necessitated by the call for a comprehensive instrument to address the smuggling of migrants in the light of the involvement of increasingly organised groups. Its purposes are: to prevent and combat the smuggling of persons; to protect the rights of migrants; to promote cooperation and information exchange; and to address the root causes of smuggling.87

The Smuggling Protocol has been criticised for placing little emphasis on responding to the root causes of smuggling. It alludes to root causes in its Preamble and Article 15 (3), which addresses development programmes and co-operation.88 The Smuggling Protocol has also been described as a law enforcement instrument, as opposed to a human rights instrument. Despite its focus on prosecution and criminalisation of the various facets of smuggling, the UNODC adopts the position that the Smuggling Protocol's provisions mandate the protection of smuggled migrants. Indeed, the Preamble to the Protocol and its Articles 2, 4, 14(1), 14 (2), 16 and 19 provide for the protection of smuggled migrants.89 Thus, UNODC encourages countries to adopt a human rights-based approach when implementing the Protocol.90

5.1 Prevention

States parties to the UNTOC are advised to adopt appropriate legislative and administrative measures to prevent transnational organised crime.91 Part III of the Protocol provides for prevention, co-operation and other measures. The measures should address public awareness, enhanced border control, documentation integrity, and development programmes. The ideal preventative starting point would be to eliminate the main "push" factor, which is the violent political turmoil prevalent in Somalia. This may not be immediately achievable. A more realistic goal is to combat corruption amongst some Kenyan immigration officials and police who facilitate unlawful entry of persons into the country. The fight against corruption should embrace measures ranging over rigorous screening procedures for recruiting public officials, anti-corruption training for key functionaries, inspections and audits, whistleblowing, and prompt investigation and prosecution of alleged incidence of corruption.92Furthermore, Kenyan criminal justice authorities need to make use of the anti-money laundering and prevention of organised crime laws to target the proceeds of economic crime. Public prosecutors need to target especially the ill-gotten assets derived from migrant smuggling. A concrete way of doing this is to resort to civil asset recovery procedures, which do not require the presence of the accused in court and where the standard of proof required for a court order to be issued is less than that required to secure a criminal conviction. This means that the proceeds of the crime may be attached without a criminal conviction. Hitting the criminal in the pocket, where it hurts most, is a strong deterrent and preventive measure.

5.1.1 Public awareness

Public awareness is aimed at addressing the existence, causes, gravity and threat of transnational organised crime.93 It is envisaged that such measures will deter migrants from submitting themselves to the smuggling process. Effective public awareness requires substantial funding, which is rarely made readily available by the governments of Kenya, Somalia or Ethiopia. The efficacy of awareness raising campaigns is also difficult to gauge, particularly where it targets vulnerable populations that lack alternatives.

5.1.2 Border control measures

Article 11 of the Smuggling Protocol requires states to enhance border protection measures to prevent and detect smuggling. The Kenya-Somalia and Kenya-Ethiopia borders are both long and porous. In order to curb irregular migration, the Kenyan Immigration Department has introduced a mobile truck unit to police the Kenya-Somalia border better.

5.1.3 Document integrity

The travel documents should be of such quality as not to be easily misused, altered, or duplicated.94 The Smuggling Protocol recommends the prohibition of commercial carriers from engaging in migrant smuggling. Carriers are responsible for confirming the integrity of travel documentation and must be punished if passengers contravene entry requirements. In extreme situations states may withdraw the carrier's licence. States need to deny entry to, or withdraw the visas of, persons implicated in smuggling of migrants. States parties are required to clarify questions on document integrity without delay in suspected cases of smuggling.95

In practice, the smuggling of persons from the Horn of Africa to South Africa does not rely on travel documentation, and there is less use of commercial carriers because of the high risk of detection.

5.1.4 Development programmes

The socioeconomic circumstances of the countries of origin, namely Ethiopia and Somalia, constitute a major push factor for migrants. Article 15 (3) of the Smuggling Protocol requires states parties to implement appropriate development programmes to address the root causes of irregular migration. Improving the socioeconomic circumstances of migrants would eradicate a major push factor. However, where such measures are implemented, they are unlikely to yield results immediately. Cooperation, both financial and technical, is indispensable for actualising such development programmes.

5.2 Protection and assistance

5.2.1 Witness protection

Smuggled migrants are privy to valuable information pertaining to the smuggling process. They are likely to be aware of the persons involved, the routes utilised and the corrupt officials and non-state actors who facilitate the movement. As a result, they can be subject to reprisals by their smugglers, especially if they co-operate with law enforcement agencies, as envisaged under Article 26 of the UNTOC. Articles 24 and 25 of the UNTOC provide for the protection of victims and witnesses and Articles 16(2) and (3) provide for the protection of smuggled migrants from violence, and assistance where their lives are at risk.

5.2.1 Human rights

Smuggled migrants are human beings first. Appropriate measures should be put in place by states parties to the Smuggling Protocol for the protection of, and assistance to, smuggled migrants. Their fundamental rights and freedoms are guaranteed in the preamble to the Protocol, which reiterates the right to life, and the right not to be subjected to torture, or inhumane or degrading treatment.96 Detention, Kenya's most common way of dealing with smuggled migrants should be a last resort.97 Where detained, migrants should be allowed to have access to their respective countries' consular services.98 Women and children are vulnerable to sexual and physical abuse during the smuggling process. The Smuggling Protocol recommends that states parties make special provision for giving assistance to this vulnerable group. Provision is also made with regard to entry onto vessels on the high seas. The integrity of and the lives, and cargo, aboard the vessel must be preserved.99

5.2.2 Assisted voluntary return

Ideally, the return of smuggled migrants should be voluntary, but this is mostly untenable because there are minimal legal channels to normalise their stay in Kenya, and the Smuggling Protocol does not compel states parties to facilitate their return. In the case of returning migrants, states parties must verify the nationality of smuggled persons and issue them with documents to facilitate their return.100 States must ensure that return takes place in an orderly and dignified way. The Smuggling Protocol contains minimum standards, and states parties should facilitate the humane return of smuggled migrants through negotiated bilateral agreements.

5.2.3 Refugees and asylum seekers

Refugees and asylum seekers benefit from international protection pursuant to the 1951 Refugee Convention, its 1967 Protocol, and the now customary law principle of non-refoulement.101In recognition of their right to international protection refugees and asylum seekers are excluded from the provisions of the Smuggling Protocol.102 They should not be discriminated against for being part of the mixed migration movement.

6 PROSECUTION AND LAW ENFORCEMENT

The UNTOC requires the criminalisation of organised criminal activity, money laundering, corruption and obstruction of justice in order to promote uniformity in the laws of states parties and to enhance cross border co-operation.103 Migrant smuggling is a predicate offence for the crimes of money laundering and terrorism, which means it is an offence, the proceeds of which could be used to commit the crime of money laundering or to finance terrorism. Corruption, on the other hand, facilitates smuggling. Furthermore, it obstructs the administration of justice, thus undermining efforts to prosecute smugglers.104 Offences aimed at criminalising the smuggling of migrants at the domestic level may be established independently of the involvement of an organised criminal group. Criminal, civil or administrative liability, including monetary sanctions, should be imposed for both natural and legal persons.105 An effective response to the smuggling of migrants requires co-operation among law enforcement agencies across states parties.106

The Smuggling Protocol criminalises the smuggling of migrants.107 It provides for the prevention of smuggling, protection of smuggled migrants and cooperation among states parties. The smuggled migrant should not be criminalised for being part of the smuggling conduct.108 However, countries maintain their sovereign right to prosecute irregular entry.

6.1 Offences and the elements of the crime

Article 6 of the Smuggling Protocol criminalises the following: smuggling of migrants; production of a fraudulent travel or identity documents; procurement, provision, or possession of a fraudulent travel or identity document; and the enabling of illegal residency. Liability for the offences must extend to attempts, accomplices, as well as to organisers and persons giving directions. Aggravating circumstances should apply for all the listed offences where circumstances endanger the life and safety of migrants or entail inhuman or degrading treatment, including the exploitation of migrants.

The UNODC has suggested additional offences under Article 6 as long as they conform to the legal system of a states party.109 Two considerations should be borne in mind by the appropriate prosecution authorities before instituting a prosecution on the basis of the suggested offences. First, the state should be able to prove the offence and not merely burden the accused with the charge. Secondly, care must be taken not to deviate too far from the primary offence.

The prosecutor must prove that the accused facilitated or assisted in the smuggling and that this was done for profit. The mental element consists, therefore, in the intention to obtain a financial or material benefit.110 The material elements of the offence are that there is a financial or material benefit accruing to the accused; and that the accused procured the illegal entry or stay, which involves the voluntary crossing of a border into a state of which the person is neither a national nor a permanent resident.111 Persons who deal with migrants other than for profit should not be held liable for the offence of migrant smuggling.

7 JURISDICTION

States parties are required to enact laws that will facilitate the prosecution of perpetrators present on their territory who have committed any of the offences listed under the UNTOC. Where parallel investigations are being conducted by one or two states parties, Article 15 (5) requires the competent authorities of those states parties to co-ordinate their investigative efforts.

8 INTERNATIONAL REGIONAL COOPERATION

The UNTOC is an instrument of co-operation. It seeks to promote uniformity among states parties in combating the offences that it creates, and Article 27 provides for cooperation among law enforcement authorities. Co-operation is envisaged in the confiscation of the proceeds of crime, extradition with or without an extradition treaty, transfer of sentenced persons, and mutual legal assistance.112 States parties are required to co-operate with developing countries and countries with transitional economies in order to enhance their financial, material and technical capacity to combat transnational organised crime.113

Part II, Article 7, of the Smuggling Protocol addresses the smuggling of migrants by sea, and provides for co-operation among states parties to prevent and suppress the smuggling of migrants pursuant to the international law of the sea. States parties with common borders, or through which the migrant smuggling routes pass, are encouraged to share information to achieve the Smuggling Protocol's aims. Information exchanged may include information relating to routes, carriers, and the identity and modalities of organised criminal groups. The exchange of information can also include legislative practices and technical information to assist law enforcement authorities to address migrant smuggling. A state party can classify information shared as confidential. Article 11(6) requires states parties to consider the establishment and maintenance of direct channels of communication among border control agencies.

The Smuggling Protocol envisages co-operation in training immigration officers to prevent and combat the smuggling of migrants;114 to promote the humane treatment of migrants; to improve detection mechanisms and intelligence gathering on the modalities of the crime; to enhance fraudulent identity document detection; and to improve the security and quality of travel documents. A critical omission is capacity building in the identification of smuggled migrants, despite such recommendation during negotiations.115 The importance of identifying smuggled migrants is elaborated below. States parties are required to consider entering into bilateral, regional, and operational agreements as means of enhancing the provisions of the Smuggling Protocol.116

8.1 Shortcomings of the Protocol

Before evaluating Kenya's' implementation of the Smuggling Protocol, it is important to highlight some of the instrument's shortcomings.117 First, the Protocol is an international co-operation agreement that addresses the organised context of smuggling, as opposed to a human rights treaty advocating for the rights of smuggled migrants. The protection mechanisms, especially as they relate to children, are insufficient. Mechanisms to identify smuggled migrants are not elaborated, and assisted return for smuggled migrants is not guaranteed by the state party of which they are nationals.

Lack of mechanisms to identify smuggled migrants, such as, the absence of procedures to identify fraudulent travel or identity documents, the lack of X-ray scanners and surveillance cameras, and laxity in developing risk profiles of smugglers and smuggled persons, are obviously problematic for numerous reasons. First, the state party which has custody of the smuggled migrants is unable to elicit important information from the migrant on the intricacies of the criminal activity. Secondly, the UNTOC creates weightier obligations with regard to the protection of victims of trafficking than the Smuggling Protocol does for smuggled migrants. It can be argued that it would be more advantageous for a state party to classify a victim of trafficking as a smuggled migrant, as a means of evading the necessary protection and assistance modalities required for trafficked migrants.

The Smuggling Protocol also fails to recognise the distinction and practical overlap between trafficked and smuggled persons.118 Smuggled migrants can, and often do, morph into victims of trafficking. The UNTOC categorises trafficked persons as victims while the status of smuggled migrants is not defined so clearly. Article 5 of the Smuggling Protocol recommends that smuggled migrants should not be criminalised merely for being part of the smuggling conduct. However, Article 6 (4) of the Protocol, allows states parties to prosecute migrants for contravening legally established entry requirements. Hitherto, states parties have concentrated on prosecuting smuggled migrants. Some states parties assist migrants based on their consent to co-operate with the law enforcement authorities. The lack of co-operation results in prosecution for illegal entry, while cooperation allows for exemption from prosecution. Articles 5 and 6 (4) may prejudice the smuggled migrant's position by requiring them to co-operate with law enforcement or face prosecution for illegal entry.

On a positive note, Article 19 excludes refugees and asylum seekers from the provisions of the Smuggling Protocol. This category of migrants has to rely frequently on smugglers for their conveyance to safety.

9 KENYAN NATIONAL LAWS ON MIGRANT SMUGGLING

The presence of smuggled migrants within a country in large numbers causes unease within governments and among citizens. Governments look to their compromised national security systems, while citizens grumble that migrants take their jobs and opportunities to do business. The primary concern for any government and citizen should be that the infiltration of smuggled migrants into the country is indicative of the proliferation of organised criminal elements.

Ideally, migrant smuggling should not be addressed under national immigration laws. The Smuggling Protocol addresses migrant smuggling occurring within an organised criminal context. An individual migrant who deliberately avoids immigration procedures and who crosses into Kenya from Ethiopia on his own is not subject to the Smuggling Protocol, but may be liable for illegal entry under Kenya's immigration laws.

Efforts to assess Kenya's implementation of the Smuggling Protocol must consider domestic measures put in place to give effect to the UNTOC. Consequentially, Kenya's legal arrangements for the treatment of smuggled migrants will be assessed in association with the immigration laws, which at present contain the bulk of the regulations governing migrant smuggling.

9.1. Kenya's procedural and legislative response

Until the present day, the modus operandi adopted to address the smuggling of migrants has been of a summary nature. Migrants intercepted during the smuggling process are arraigned before subordinate courts by immigration officers vested with prosecutorial powers. They are then charged with being "unlawfully present" in Kenya. The accused invariably plead guilty to the offence and are fined or sentenced to not more than 12 months' imprisonment in lieu of a fine. This sentence is accompanied by a repatriation order which comes into effect once the prison sentence has been served. The Kenyan Penal Code, read together with the Immigration Act (now repealed), provides the impetus for the repatriation order.119 The relevant provision states that where a person is convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment for a period not exceeding twelve months, a court may order that the person be removed from Kenya, immediately or on completion of any sentence of imprisonment.

The Kenyan police have been criticised for their obsession with arresting arriving Somalis and charging them or threatening to charge them with being present in Kenya unlawfully.120 Threats by police are aimed at extorting bribes from the migrants. Police stationed in the vicinity of the Liboi border area extort money from thousands of Somali asylum seekers who cross the border in vehicles with the help of smugglers.121

In the unreported case of R v Hussein Galgalo and two others122, the accused persons of Somali origin were charged with being in Kenya unlawfully, in violation of section 13 (2) of the Immigration Act (now repealed). They were found guilty and subsequently sentenced to six months' imprisonment, after which they were subject to repatriation. A judicial review of the decision set aside the conviction on the ground that the plea was administered improperly, apart from the fact that the accused persons were not provided with an interpreter during the trial. This case is illustrative of the treatment meted out to smuggled migrants in Kenya when they are intercepted by law enforcement officials.

Until the recent enactment of the Kenya Immigration and Citizenship Act,123 law enforcement officials were in a quandary as to the appropriate offences with which to charge the facilitators and profiteers of human smuggling. Currently, the treatment of smuggled migrants is still reminiscent of the now repealed, archaic 1967 Immigration Act. In the Mohamed Sirajesh Mohamed case,124 the accused, a Somali national, was found without travel documents after the public transport vehicle in which he found himself, was intercepted at a road block about 60 kilometres from Nairobi. The accused was charged in the Senior Resident Magistrates' Court at Kajiado on 7 November 2011 with offences under sections 53 (1) and (2) of the Citizenship Act. He pleaded guilty and on this plea was liable to a fine of Kenyan Shillings ( Kshs) 200 000 or 12 months imprisonment in lieu of the fine. The court issued an additional order that he be repatriated. As a result of the intervention of the UNHCR, acting through a legal aid organisation, Kituo cha Sheria, the repatriation order was substituted by an order that Mohamed be handed over to the UNHCR as a person of concern.

9.2 Laws against organised crime

9.2.1 Prevention of Organised Crimes Act of 2010

The Prevention of Organised Crimes Act is a national law aimed at the prevention and punishment of organised crime and the recovery of the proceeds of organised crime.125It came into force on 23 November 2010 and domesticates the UNTOC. The Act criminalises organised criminal activities and the obstruction of justice. It also provides for the tracing, confiscation, seizure and forfeiture of property. This law mirrors the UNTOC in defining an organised criminal group. However, under the Act, a serious crime is any offence punishable by a prison term of at least six months, pursuant to the Laws of Kenya, as opposed to the four years' imprisonment that qualify an offence as a serious crime under the UNTOC.126

An additional proviso to the serious crime definition under the Prevention of Organised Crimes Act 6 of 2010 is dual criminality. Where criminal conduct committed in a foreign jurisdiction is also criminalised under the Laws of Kenya, such conduct constitutes a serious crime. A serious crime under Section 2 of the Act is a felony. However, Chapter 63 of the Penal Code classifies an offence punishable by six months imprisonment or less as a misdemeanour. This creates a conflict.

According to the Act, participation in an organised criminal activity is proscribed. The penalty is imprisonment for a term not exceeding 15 years , or a fine not exceeding Kshs 5 million, (approximately US$59 600) or both. A person is deemed to engage in organised criminal activity where such a person: is a member of an organised criminal group; recruits members; acts in concert with other persons in committing a serious offence for profit; uses his or her membership to direct the commission of a serious offence; or threatens violence or retaliation in connection with the organised criminal group, amongst other activities.127

The Prevention of Organised Crimes Act was enacted to stem the increase in the incidence of kidnapping and the extortion of ransoms and drug trafficking, the criminal activities of the al Qaeda linked terrorist group al Shabaab, and to combat the criminal activities of the outlawed Mungiki sect, which is a banned ethnic organisation.128 The provisions of section 3, read together with section 4, can be used to address the smuggling of migrants. Similarities between offences in the Act and Article 6 of the Smuggling Protocol include: aggravated circumstances resulting from organised criminal activity; membership of an organised criminal group; conduct related to document fraud; retaliation or violence against smuggled migrants; and attempting or aiding and abetting any of the above offences.

In determining whether someone is a member of an organised criminal group, the court needs to consider the person's own admission, the reasonable circumstances pointing to membership, visible affiliation with an organised criminal group, and receipt of financial or material benefit from such group.129

The ambit of the Prevention of Organised Crimes Act is narrower than that of the UNTOC, which it seeks to domesticate. The Act does not provide for the protection of victims, as proposed during debate after the Bill's second reading.130 The law's connection with trafficking in persons as an organised crime was recognised, but no similar correlation was drawn with regard to the smuggling of migrants. During the debate, it was further noted that the provisions of the UNTOC were not adequately addressed by the debated draft. The draft was nevertheless more or less passed in that form. As such, it leaves gaps in crafting an appropriate response to the progressively sophisticated mechanisms and modalities of organised crime, including the smuggling of migrants, which it does not consider directly.131

9.2.2 Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2009

The Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act (the Proceeds of Crime Act) was enacted in 2009 to criminalise money laundering. The Act provides for the combating of the crime as well as the identification, tracing, freezing, seizure and confiscation of the proceeds of crime.132 The Act makes all crimes predicate offences.133 During the second reading of the Bill, the Minster for Finance highlighted smuggling and prostitution rings as examples of offences where large amounts of illegal proceeds are generated and laundered to enable criminals to enjoy their ill-gotten gains.134 In this regard, where a smuggling related offence is committed under the Prevention of Organised Crimes Act, then it follows that the proceeds of this offence, where they are disguised or there is an attempt to disguise them, should fall under the Proceeds of Crime Act. Section 2 defines proceeds of crime as any property or economic advantage realised in connection with an offence, including property that is converted or transformed successfully, as well as economic gains realised from that property from the time the offence was committed.

Sections 3, 4 and 7 of the Proceeds of Crime Act establish the offence of money laundering. Money laundering occurs where a person knowingly deals with the proceeds of crime in order to conceal their nature, source, location, disposition movement or ownership; enables another person who commits an offence to avoid prosecution; removes or diminishes any property realized from the commission of an offence; knowingly acquires, uses, or has possession of property that constitutes the whole or part of the proceeds of an offence; and transmits and receives a monetary instrument with the intention of committing an offence.135

Penalties are provided in section 16. Natural persons are liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years, and/or a fine not exceeding Kshs 5 million. Where the value of the property laundered exceeds the value of the fine, the amount of the fine shall be commensurate with the value of the property. In the case of corporate bodies, they shall be liable to a fine not exceeding Kshs 25 million or the value of the property laundered, whichever is higher.

The Proceeds of Crime Act is not without controversy. It is linked to the International Money Laundering Abetment and Anti-Terrorism Financing Act of 2001, Act 3 of the dreaded American US Patriot Act, which contains radical measures to combat the financing of terrorism.136During debate, the Bill was criticised for being contextually misplaced in a country whose economy is primarily cash-based, with little data or consumer protection safeguards.137

9.1.3 Mutual Legal Assistance Act 2011

The Mutual Legal Assistance Act of 2011 governs situations in which a relevant agreement for mutual legal assistance exists, as well as where it does not. It does not preclude agreements or arrangements in respect of cooperation between Kenya, other States and international entities on legal assistance, and allows broader assistance than may be provided for in an agreement.138 Specific requests for assistance directed to Kenya may relate to the examination and attendance of witnesses, service of documents, provision or production of records, and lending of exhibits, among others.139 Broadly speaking, it may constitute a basis for co-operation in information gathering and investigation of the transnational organized movement of migrants from the Horn of Africa and beyond.

10 IMMIGRATION AND PENAL LAWS

10.1 The Citizenship and Immigration Act of 2011

Section 2 of the Citizenship Act mirrors the Smuggling Protocol definition of migrant smuggling, except that migrant smuggling under the Citizenship Act applies to both illegal entry and exit. Trafficking in persons is also defined in section 2 of the Citizenship Act by way of cross-referencing the Counter Trafficking in Persons Act of 2010, which largely adopted the definition in the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons. According to the Citizenship Act, a smuggled migrant is a victim of a crime. Internationally, the smuggled migrant is not recognised as a victim because he/she consents to being smuggled. However, the harsh realities of the smuggling process often leave the migrant a victim of one crime or another. The Citizenship Act exempts smuggled migrants who are employed irregularly in Kenya from prosecution, provided that they are willing to assist in the prosecution of the smuggler.140

In addition to defining the offence of migrant smuggling, the Citizenship Act defines other related organised criminal offences. It makes provision for the punishment of carriers engaged in the smuggling of migrants, as recommended by the Smuggling Protocol. However, the smuggled migrant is not exempted from criminal prosecution as required by the Smuggling Protocol. Numerous document-related offences, including harbouring and interfering with the duties of an immigration officer, either through misrepresentation or exerting undue influence, are enumerated in the Citizenship Act. Many of the offences can be used to prosecute smugglers. The Citizenship Act recognises the right of entry of refugees and asylum seekers, and provides for holding facilities for persons of concern to immigration officers. Such facilities can provide temporary shelter and access to basic amenities for smuggled migrants who have suffered abuse during their journey.

The Citizenship Act represents the first attempt by the Kenyan legislature to encapsulate the offence of migrant smuggling. However, it is not recommended as an international best practice to include smuggling and related offences in domestic immigration law. The offence of smuggling should be dealt with separately under the organised crime framework of a state party.

The possible complicity of immigration and law enforcement officers, which occurs in many cases of smuggling, is not directly considered in the Citizenship Act. In sum, the Citizenship Act does not provide adequately for the protection of smuggled migrants, the prevention of smuggling, or co-operation among relevant actors and states, which is essential in combating and addressing the smuggling of migrants. However, all the statutes discussed above can be utilised by law enforcement authorities to prosecute various facets of the smuggling offence.

11 RECOMMENDATIONS

The tide of migration from the Horn of Africa southwards is not diminishing. It is likely to continue, mutating into more sophisticated methods aimed at preventing detection. Additionally, opportunistic criminals will continue to scuffle for the spoils of the irregular movement of people across borders. An isolated response by Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya would be too narrow and simplistic for such a complex migratory phenomenon. However, given the centrality of Kenya to the migrant movement, a coalition of interventions by these three countries may actually hold the key to stemming the movement southwards. At the very least, a co-ordinated response to the three countries may succeed in sealing corruption loopholes, or harnessing some sort of economic gain from the movement for the countries involved.

11.1 Prevention