Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Law, Democracy and Development

versão On-line ISSN 2077-4907

versão impressa ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.18 Cape Town 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v18i1.10

The Amended Government Procurement Agreement: Challenges and opportunities for South Africa

Umakrishnan Kollamparambil*

Associate Professor, University of the Witwatersrand

1 INTRODUCTION

General government procurement (including for defence) accounts for 20 per cent and 15 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and non-OECD countries, respectively.1 Despite liberalisation of trade under the General Agreement on Tarrifs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO), government procurement largely continues to have high levels of home-bias. This is primarily so because a multiplicity of objectives drive government procurement. Considerations of government procurement as a policy instrument very often override cost-effectiveness as the primary consideration in determining it. For example, government procurement is commonly used as a policy tool for developing target sections of populations, industry, regions etc. In addition, according to Keynesian arguments, government procurement is the key instrument for fiscal policy intervention to kick-start a slowing economy. These multiple objectives create complexity because there are usually trade-offs involved between them in that attaining one is usually at the cost of the another.

The plurilateral Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) is an attempt to liberalise government procurement necessitated by the fact that it has been exempted from the rules of National Treatment, Non-discrimination and Most Favoured Nation (MFN) under both the GATT and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Attempts made during the Singapore Round to include discussion of transparency in government procurement under the multilateral ambit of the WTO discussions in the Doha Round had to be abandoned following the stalemate there. It is for this reason that the plurilateral Government Procurement Agreement, (the amended GPA (AGPA)) signed in March 2012 by 42 countries is being hailed as the single largest success under the WTO since the start of Doha Round of discussions. The members at present are mostly from the European Union and other developed countries. However, developing countries, like China, are currently at advanced stages of negotiation to become parties to the GPA. There are 22 other countries that have taken on observer status at the GPA, simply to observe the workings of the Agreement closely with no commitments/obligations. South Africa is neither a party to the AGPA nor does it have observer status.

It is in this context that this article analyses the challenges and opportunities for South Africa in joining the AGPA. The purpose of the article is to determine how best South Africa can balance its multiple objectives of government procurement through an analysis of its existing procurement framework and the implications of the Agreement. While at first glance the argument that immediate adherence to the provisions of the Agreement will have the effect of negating the aim of the redistribution of wealth as national firms may not yet be able to compete internationally, may seem valid, it will be contended that the AGPA can be used to the benefit of South Africa provided membership thereof is correctly negotiated. The benefits in doing so can bring about savings to the economy through reduced corruption and better value for money in government procurement which can be more effectively used for undertaking sustainable interventions in the economy, bearing in mind the ultimate objectives of better redistribution and faster development of South Africa's population. In order to achieve this, it is recommended that South Africa should move towards accession to the AGPA to ensure that corruption is limited by international monitoring and competition, but that this should be a calibrated process initiated through multiple reservations to the Agreement and amended over time.

The structure of the article is as follows: section 2 introduces the nature and the characteristics and issues relating to government procurement. This is followed in Section 3 by a review of South Africa's procurement policy and issues relating thereto. Section 4 traces the history of the GPA and examines its major clauses. An analysis of the implications of the AGPA for South Africa is undertaken in section 5. The way forward for South Africa is charted in section 6. Section 7 contains the conclusions.

2 CHARACTERISTICS OF GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT

The two main characteristics of government procurement markets that differentiate them from other goods/services markets are their low contestability and prevalence of the principle-agent problem. This section discusses how low contestability and the principal-agent problem in government procurement markets necessitate strict monitoring and regulation and further highlights the difficulties relating to effective regulation, and monitoring that have led to a situation of high levels of corruption in government contracts.

The "home bias" or protection of government procurement markets against foreign competition is driven partially by the view that the nation's money must be spent on the nation. Although seemingly a narrow stance, this position is not without economic logic, at least in the shortrun. Following Keynesian argument, the effectiveness of a money multiplier is greatest if there is no leakage of fiscal expenditure outside the domestic economy. The New Trade theorists2 as well as the 'new' New Trade theorists3 would adopt a similar view of protection by arguing that, given imperfect competition and increasing economies of scale, it is sensible to offer protection to firms in their infancy to allow them to grow and become capable to compete internationally.

On the other hand, the Neo-classical trade theorists would oppose the argument saying that by following a policy of protectionism, the government ends up paying more and hence has to limit its purchases or incur higher fiscal deficits.4 The general equilibrium analysis conclusions are that the abnormal profits enjoyed by firms in industries with "home bias" in turn leads to misallocation of resources and drives up factor prices making other sectors of the economy uncompetitive as well. This is countered by the argument that the abnormal profits enjoyed in the short run through a ban on imports are competed away by new domestic entrants provided there are no policy or natural entry barriers.5

According to the theory of contestable markets, potential competition as well as actual competition will influence market performance, and the freedom of firm entry and exit, price flexibility, and equal access of competitors are likely to offer improvements over the rigid regulatory practices of the past.6 Although this cannot be interpreted, in the absence of perfect competition, as a message that policy intervention in market processes is unnecessary in a contestable market, in principle, in the absence of contestability the cost of regulation is higher.7

Despite these arguments for liberalisation in government procurement markets, the low contestability in government procurement is evident from the high levels of "home bias" observed even in the most liberalised economies. Even in countries where the trade to GDP ratio is very high, 90 per cent or more of all procurement contracts are estimated to be allocated to domestic firms8. The import share of government procurement for seven OECD countries is estimated to be systematically lower to that of the private sector and is indicative of "home bias" in government purchases.9

The instruments used to enforce the "home bias" that is observed in most countries have been: (a) an outright ban on foreign suppliers; (b)cost discrimination against foreign suppliers by imposing import tariffs or additional conditions to be satisfied to participate in the procurement process; or (c) price margins in favour of local suppliers.10 The first two instruments invariably lead to government procuring at higher costs, while the price margins if implemented correctly can lead to a good mix of competitive prices as well as "home bias."11

The second characteristic of government procurement relates to the principal -agent problem. The problem exists in that the agent, the procurement committee/officer, colludes with a bidder and does not act in the best interest of the country and its people. This problem is usually encountered in businesses by putting in place the right incentives for the agent to align his interests with those of the principal. However, given the multiplicity of objectives of government procurement, it is difficult to measure the performance of an agent for the purpose of structuring the incentive. The other option is to monitor the actions of the agent closely. Given the high levels of information asymmetry due to the distance between the principal and the agent, the costs involved in instituting effective monitoring are high and its effectiveness is low.

As pointed out by the UNCTAD secretariat, "the ideal level of competition for public contracts is not always realized in practice for reasons that may relate to (i) the regulatory framework for public procurement; (ii) market characteristics; (iii) collusive behaviour of bidders; and (iv) further factors."12 This has led to high levels of corruption in government procurement, and it is safe to say that although the degree of corruption might differ between countries corruption itself can be said to be universal.13

3 GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA

This section is divided into two parts. First, an examination of some data relating to government procurement, and secondly, an analysis of the policy framework in South Africa highlighting some of its important shortcomings and the fallout therefrom.

3.1 Recent trends and composition

Being a non-GPA country, procurement data for South Africa are very hard to come by. Total general government procurement is estimated by using the methodology adopted by Shingal.14 Using South African Reserve Bank data, General Government Purchases (GGP) are estimated as follows:

GGP= General government final consumption + General government fixed investment -General government wages and salaries- General government subsidies- General government current and capital transfer payments

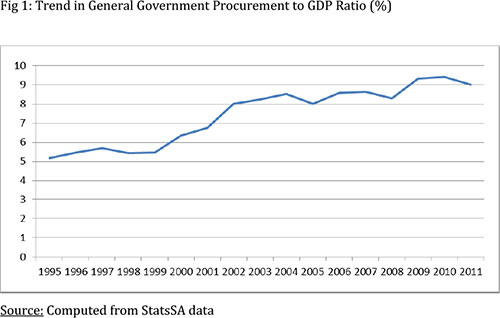

The estimate for 2011 indicates that the government procurement of South Africa accounts for R267 billion or 9 per cent of its GDP. This ratio estimated over time indicates that government procurement has been steadily increasing from a level of 5.2 per cent in 2005 (Fig 1). However, it continues to be much lower than the ratio of developed countries.

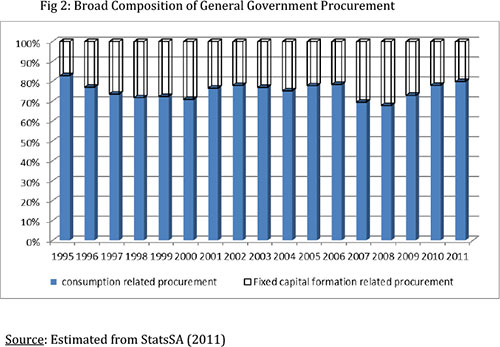

Looking at the composition of government procurement, the bulk of the expenditure can be classified as final consumption expenditure, but fixed investments are still significant at over 20 per cent (Fig. 2). This has remained more or less consistent over the period of analysis except for the spike in fixed investments in the years preceding the 2010 FIFA World Cup hosted by South Africa. During these years the government had intervened in a big way in infrastructural development, resulting in the share of fixed investments going up to over 30 per cent of total government procurement.

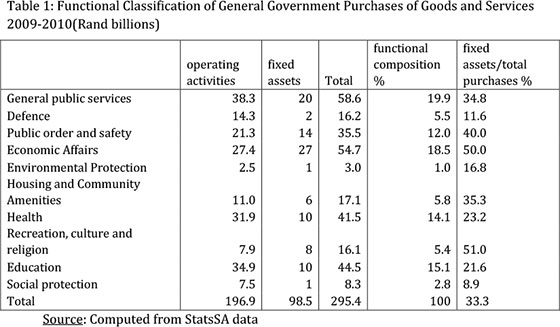

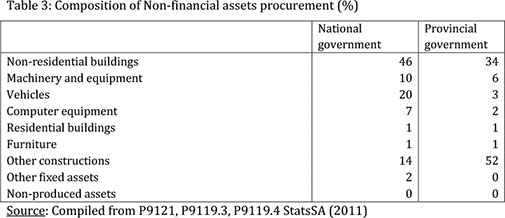

The functional classification15 of government procurement in South Africa indicates that 70 per cent of the total is accounted for by general public services, economic affairs, education and health related purposes (Table 1). The procurement expenses of the National government and the nine provincial governments indicate that the outlays of the provincial governments are almost double that of the national government (Table 2). The Table does not contain information on the allocations to municipalities, higher education institutions and extra budgetary accounts and funds. The share of non-financial fixed assets to total procurement is higher for provincial governments as compared to national government (Table 2). The composition of non-financial assets procurement indicates construction activities to be the single largest item, accounting for 86 per cent and 60 per cent for provincial governments and national government, respectively (Table 3).

3.2 POLICY FRAMEWORK AND SHORTCOMINGS

Although the ratio of government procurement to GDP of South Africa is low compared to that of developed countries, the relevance of government procurement as a policy instrument in South Africa is underlined by the fact that it finds mention in its Constitution. The South African Constitution stresses five tenets of public procurement: fairness, transparency, equity, cost-effectiveness and competitiveness.17 The multiplicity of the requirements with regard to government procurement is clear; however, the relationship between them is not because of the evident trade-offs between these tenets. There is however an emphasis in the Constitution on the need to correct the inequality of South African society and for the use of government procurement as a policy tool in this direction.18

Section 9(2) of the Constitution dictates that "to promote the achievement of equality, legislative and other measures designed to protect and advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken." With regard to procurement specifically, section 217(2) provides for the protection or advancement of persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination.

As required by section 217(2) of the Constitution, a framework for preferential procurement was set up in the form of the Preferential Public Procurement Framework19 (PPPFA). In terms of the PPPFA, a points system20 for procurement was introduced to provide support to the historically disadvantaged individuals (HDIs)21 of society. Over and above the awarding of preference points in favour of HDls, the following activities may be regarded as a contribution towards achieving the goals of the Reconstruction and Development Programme22:

a) The promotion of South African owned enterprises;

b) The promotion of export orientated production to create jobs;

c) The promotion of SMMES;

d) The creation of new jobs or the intensification of labour absorption;

e) The promotion of enterprises located in a specific province for work to be done or services to be rendered in that province;

f) The promotion of enterprises located in a specific region for work to be done or services to be rendered in that region;

g) The promotion of enterprises located in a specific municipal area for work to be done or services to be rendered in that municipal area;

h) The promotion of enterprises located in rural areas:

i) The empowerment of the work force by standardising the level of skill and knowledge of workers;

j) The development of human resources, including by assisting in tertiary and other advanced training programmes, in line with key indicators such as percentage of wage bill spent on education and training and improvement of management skills; and

k) The upliftment of communities through, but not limited to, housing, transport, schools, infrastructure donations, and charity organisations.

While the guidelines relating to the PPPFA cover issues, such as, outsourcing and local content estimation, even to the detail of which exchange rate is to be used to convert the import content of goods, their implementation are not without issues. Although the evaluation of a tender contract must be objective and a contract should be awarded to the tenderer who achieves the highest score,23 a contract may be awarded to a tenderer that did not score the highest total number of points if additional objective criteria to those contained in section 2(1)(d) justify the award to another tenderer.24 These criteria, which are additional to the preferential procurement criteria, are neither defined in the PPPFA nor its Procurement Regulations but must be "clearly specified in the invitation to submit a tender."25 Furthermore, in certain instances, contracts may be awarded without taking into account the preferential procurement policy framework if it is in the national security interest, the likely tenderers are international suppliers, or it is in the public interest.26 Should an organ of state wish to exempt itself from any or all of the provisions of the PPPFA, consent must be obtained from the Minister of Finance.

Other weak links in the system are the Bid Evaluation Committee and the Adjudication Committee. There is nothing in the law that makes it illegal for either politicians or government officials and their family members to submit tenders provided that they are not part of these Committees. However, the Auditor-General's Reports27 indicate that the number of beneficiaries of government contracts is disproportionality high at every level of government indicating rampant conflict of interest in decision making. This together with loopholes that exist, such as, the exceptions to PPPFA clauses and the clause that allows a contract to be awarded to a tenderer that did not score the highest total number of points if "objective criteria"28 in addition to "specific goals"29 justify the award to another tenderer.

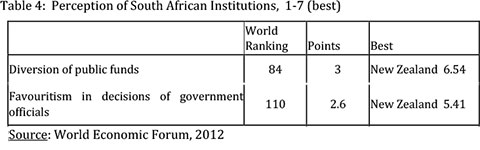

This has led to widespread favouritism and corruption in the decision making system. This has emerged during court cases and investigations. The scale of it is captured by various international organisations, such as, Transparency International and the World Economic Forum. According to Transparency International, South Africa ranks 84 on the world's Corruption Perception Index. The World Economic Forum also scores South Africa dismally in relation to other countries with regard to favouritism in decision making and diversion of public funds (Table 4).

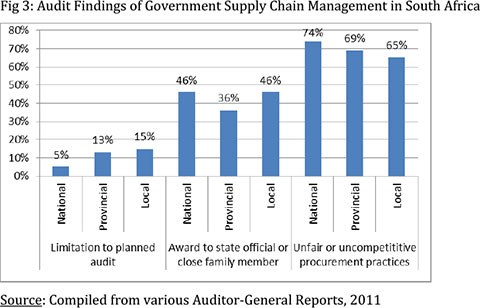

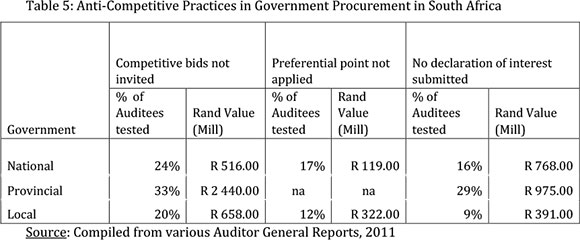

The Report by the Auditor-General of South Africa has highlighted widespread malpractices in the supply chain management of government (Fig 3). The high proportion of contracts awarded to government officials or their close family members and other forms of uncompetitive practices at every level of government, raise a red flag. Some of these unfair or uncompetitive practices are further unpacked in Table 5.

Of greater concern is that the amounts presented in Table 5 are from a very small sample, and that the figure for the total government procurement is likely to be more than three times greater. The other issues relating to the current preferential procurement practices in South Africa are the lack of information and transparency. Moreover, there is no dedicated mechanism to challenge an award of a contract or any dispute settlement mechanism for government procurement. This makes it difficult for competitors to query or monitor unfair practices facilitating corruption.

This method of targetted procurement basically acts in fact as a restriction on open competition and hence leads to monopolistic practices. Restricted competition also increases the possibility of bid rigging, where competitors collude in fixing tenders.

It might be rotation bid, or an agreement to outsource part of the contract, or even an outright payment settlement. Evidence of such activities in South Africa which were identified and prosecuted by the Competition Commission is listed in the OECD Report.30 These include supplies of pharmaceuticals to public hospitals, buyers of scrap metal from Transnet (then Spoornet), suppliers of concrete infrastructural products to municipalities, etc. The Report, however, also points to a large degree of corporate leniency in this regard as well.

Lastly, there is no study to indicate or evaluate how well targetted procurement has served society in general. The effectiveness of it as a tool to bring about equity in society has not yet been evaluated in full measure.31 The Country Procurement Assessment Report on South Africa by the World Bank in (2003)32 lists in detail the shortcomings of the procurement process in South Africa and highlights the lack of significant quantitative data on the cost and outcome of the preferential system.

In the absence of a detailed impact evaluation, conclusions based on trends in measures in regard to inequality indicate that the PPPFA has not led to a reduction in inequality. In fact the Gini coefficient which stood at 57.8 in 2000 went up to 63.1 in 2009 (World Bank)33 indicating that inequality in South African society has increased despite the implementation of the PPPFA.

Studies indicate that 80% of SMEs fail during their first year and 60% of the survivors fail in their second year. 34 According to Luiz35 government procurement is too complicated, inflexible and inadequate for SMEs and while there is no denying the relevance of supporting SMMEs for employment generation and growth in South Africa, the indications are that the full potential is not being achieved under the PPPFA mandate.

It is in this context of crony capitalism and lack of evidence of reduction in inequality the question whether South Africa can benefit from GPA membership. The next section details the evolution of the GPA and its important clauses.

4 EVOLUTION OF THE GPA AND KEY CLAUSES

Hailed as the biggest victory for liberalisation within the WTO since the start of the Doha negotiations, the AGPA was formally adopted on 30 March 2012. Although within the framework of the WTO, the AGPA is a plurilateral agreement administered by the Committee on Public Procurement, currently with 42 WTO members, and nine other WTO member countries negotiating their entry into the Agreement.

The need for a separate agreement on government procurement was necessitated by the fact that although the National Treatment and Non-discrimination treatment obligations exist under the GATT, government procurement is explicitly excluded from these obligations (Article III.8 of the GATT). Likewise, the GATS exempts government procurement in respect of market access, MFN and National Treatment (Article XIII.1). Little progress has been made in including government procurement under the multilateral ambit since the Singapore Round, which tried to develop an agreement on transparency in procurement activity, and the Fourth Ministerial Conference at Doha in 2001, which aimed for negotiations on procurement to begin after the Fifth Ministerial Conference at Cancun. However, strong opposition on procurement and other issues from many member countries, led to the Fifth Ministerial meeting at Cancun ending without any decision. Furthermore, as part of the General Council Agreement reached to put the general negotiations back on track, it was decided in 2004 that no further negotiation would take place on transparency in government procurement during the Doha Round discussions.

Given this background, a plurilateral agreement on government procurement is seen as a major step forward in liberalising government procurement. The origins of the GPA can be traced to the first plurilateral agreement on government procurement known as the Tokyo Round Procurement Code (Code), negotiated in 1979 and entered into force on 1 January 1981 with 12 members, to bring about transparency and non-discrimination in government purchases. The purpose was to open up government procurement of goods to international competition by ensuring that parties do not protect domestic products or suppliers, or discriminate against foreign products or suppliers (Article II of the Code). This was a very restricted agreement, applying only to central government procurement and only to goods and not services and, having a relatively higher financial threshold at SDR150000. Although very narrow, the Code continues to be the basis of the present AGPA. The Code included a clause for transparency aimed at detection of violation of the basic tenets of MFN and Non-discrimination policies. It also laid down procedural obligations on rules of technical specification, advertising of information on procurement, selection based on pre-disclosed criteria, and provision of information with regards to the successful bid to other contending suppliers on request. These continue to be the basis of the AGPA.

Further negotiations at the Uruguay Round (concluded in 1994) led to the Revised GPA (URGPA) which took effect on 1 January 1996. According to estimates, this achieved a ten-fold expansion of coverage by, among other things, extending coverage to services (including construction services) procurement.36 Equally importantly, this extended international competition in government procurement to include national and local government entities (at the sub-central level, for example, states, provinces, departments and prefectures), as well as procurement by public utilities. The 1994 URGPA took a watershed step forward by introducing in Article XX an independent review body where suppliers could challenge both procurement procedures as well as decisions.

Article XX sets out minimum standards concerning the nature of the review body and the procedure for hearing the challenge, and also requires certain specified remedies to be available, namely interim measures, damages (though these may be limited to costs) and correction of violations'.37 In addition, it introduced the application of the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding to bid challenges.

A review of the URGPA was initiated as early as 1997 based on Article XXIV.7 of the URGPA requiring regular negotiations among the Parties for continued improvement of the Agreement by simplifying it, extending its coverage, eliminating the remaining discriminatory measures applied by Parties, and addressing issues arising from the use of information technology in procurement.

Continuing negotiations post-1996 have now culminated in the amended GPA (AGPA) which came into effect in March 2012. The most important feature of this Agreement (with its 44 members) is the inclusion of fighting corruption and conflict of interest as a specific purpose and objective. In the earlier versions, fighting corruption was consider to be a by-product that would be achieved through increased transparency and competition. The AGPA is a further improvement in that it has modernised procedures (in keeping with developments in IT providing for e-bid submissions, etc), and simplified (in terms of data submission requirements) and included greater flexibility for developing countries. It continues to have the provisions for Special and Differential (S&D) treatment for developing countries to negotiate offsets at the time of accession or soon thereafter. These however are to be transitory measures whose duration has again to be negotiated.

Although the AGPA does not contain a remarkable departure from the earlier text and maintains on the basic tenets of non-discrimination and transparency, it has considerably simplified and enhanced flexibility. Moroever it has, very importantly, recognised the value of the GPA and the resulting transparency not just in achieving value for public money through competitive processes but by explicitly recognising the objective of fighting corruption. The Preamble states:

Recognizing the importance of transparent measures regarding government procurement, of carrying out procurements in a transparent and impartial manner and of avoiding conflicts of interest and corrupt practices, in accordance with applicable international instruments, such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption.

Furthermore, Article IV.4 (Conduct) reinforces the need for transparency in procurement so that it avoids conflicts of interest (Article IV.4b) and prevents corrupt practices (Article IV.4c). In order to achieve this, Articles VI and VII state the procedural rules to ensure transparency for procurement through tender laws, with respect to technical specifications, advertising and information dissemination regarding forthcoming tenders, tender scrutiny and valuation criteria, time limits, negotiations with suppliers, etc. Directed/limited tendering is allowed only in exceptional circumstances while the multi-use list of approved suppliers approach is acceptable as long as information on how to get on the list is made publicly available.

The other critical components of the AGPA relate to offsets, domestic review procedures, provisions regarding dispute settlement and future works programme. Article IV.6 of the AGPA prohibits the enforcement of offsets by a Party (including its procuring entities) in the qualification, selection, and evaluation of tenders as well as in the award of contracts for covered procurement. However, very importantly, the AGPA (Article V) recognises the need for S&D treatment to be accorded to developing countries in keeping with their development, financial and trade needs. It makes allowance for developing countries to negotiate at the time of accession the conditions for the use of offsets (or within 3 or 5 years of accession for delayed applications by a developing or least developed country, respectively, as per Article V.4). However, the offsets allowed are transitory and the developing country must list in its Annex 7 to Appendix I the agreed implementation period, the specific obligation subject to the implementation period and any interim obligation with which it has agreed to comply during the implementation period (Article V.5). Provisions for regular review have been buil-in, with Article V.10 stipulating that the Committee shall review the operation and effectiveness of this Article every five years.

The AGPA (Article XVIII "Domestic Review Procedures") stipulates that each Party shall establish or designate at least one impartial judicial or administrative authority (subject to judicial review) that is independent of its procuring entities to receive and review a challenge by a supplier arising in the context of a covered procurement in a timely, effective, transparent and non-discriminatory manner that is not prejudicial to the supplier's participation in ongoing or future procurement. Moreover, each Party must adopt and maintain procedures for corrective action or compensation for the loss or damages suffered. In addition to domestic review procedures, Article XX ("Consultations and Dispute Settlement") affords each Party recourse to the provisions of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (with the exception of paragraph 3 of Article 22 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding) with respect to any matter affecting the operation of the AGPA.

The AGPA has added to market access coverage by including new procurement entities, reducing the negative list, and lowering the procurement threshold to SDR 130,000. The AGPA is set to increase its relevance, with countries like China in advanced stages of negotiation to accede to the Agreement.

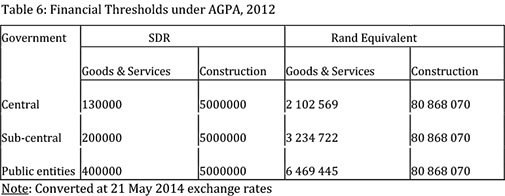

Table 6 on financial thresholds indicates the average thresholds according to categories. It is evident that the thresholds are relatively high. Contracts under these values can continue to be reserved for targetted procurement.

While the AGPA in its current form can be improved by bringing development aid within its ambit, and increasing clarity on disadvantaged groups, etc., it is an evolving institution. The future works programme under Article XXII.7 makes commitments for continued discussions among the Parties to improve the AGPA, by reducing discriminatory measures and extending its coverage. More specifically, the path forward is charted in Article XXII.8 "through the adoption of work programmes on the treatment of SME's; collection and dissemination of statistical data; the treatment of sustainable procurement; exclusions and restrictions in Parties' Annexes; and safety standards in international procurement." Herein lies the uncertainty regarding the future for developing countries. While the agenda for discussions includes a framework for the treatment of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), it also includes more controversial items, such as, sustainable procurement and safety standards in international procurement, with which developing countries have had issues within the broader WTO round of discussions.

5 IMPLICATIONS FOR SOUTH AFRICA

An analysis of the implications of the AGPA for South Africa indicates that there are costs as well as benefits to becoming a AGPA member. GPA membership would result in contestability of government procurement markets and the resulting increased competition would ensure better value for money in government procurement. This in turn would mean the possibility of either procuring more for the same amount, or re-allocation of government funds for developmental intervention, or simply lower fiscal deficits. The emphasis on transparency and the explicit mention of reduction of corruption as an important objective of the AGPA will result in better governance and a reduction in crony capitalism with all its evils. The impact of market contestability and transparency is not to be neglected as estimates show that the implementation of the AGPA in the European Union led to a saving of 30 per cent.38

Liberalisation of markets results in increased trade and liberalisation of government procurement is also likely to result in increased trade. This therefore implies that the countries must have the necessary infrastructure to handle the increase in trade. The strength of South Africa primarily lies in its good infrastructure which is equipped to handle an increase in trade volumes as a result of the liberalisation of government procurement. The Logistics Performance Index of 3.46 for South Africa is comparable to that of developed countries.39

Liberalisation, however, is not a guarantee for competitive practices. There is increasing evidence of international bid rigging and monopolistic practices in public procurement.40 These threats emanate from unfair trade practices like dumping and cartel behaviour through bid rigging and collusive pricing. In order to get the benefit of liberalisation, it is important that policies and agencies equipped to identify and deal with uncompetitive practices are strong. The anti-monopoly policy and Competition Commission of South Africa are worthy of mention in this regard. The World Economic Forum41 ranks South Africa sixth in the world for effectiveness of its anti-monopoly policy. The Competition Commission of South Africa has a reputation as a world-class agency and has won the 2011 award for "Agency of the Year in Asia-Pacific, Middle East & Africa."42 There is, however, the need for co-operation between the anti-trust agencies of different countries to counter international cartels. This need cannot be emphasised enough and this is an area where work needs to progress faster. It is important for an international framework to be developed for co-operation between the anti-trust agencies of various countries in countering this behaviour.

The above discussion does not imply, however, that South Africa is prepared to fully liberalise its markets. It is important for South Africa to take advantage of the provisions of S&D treatment for developing countries in the form of transitory offsets to develop its industry, regions, and sections of society. The AGPA provides for financial limits below which the Members are not compelled to invite international price competition (Table 6) and this will restrict competition to Small, Medium and Micro-Enterprises (SMMEs) and protect the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) firms.

While S&D treatment for developing countries would allow South Africa to exclude from the AGPA clauses of liberalisation sectors that it feels need to be temporarily protected before they can be opened up for competition, these offsets have to be negotiated at the time of accession to the GPA. This in turn requires an in-depth understanding of the procurement market of South Africa. Research in the area of South African procurement markets is at a very nascent stage and further work is critical to make informed decisions. Disaggregate data on procurement is necessary for this. Recognising this need, the National Treasury has initiated the process of compiling a database on government tenders from national departments, provincial governments and Municipal bodies.

There are also additional cost implications to becoming AGPA compliant. The AGPA requires that its Member countries establish an independent oversight agency and a dispute settlement system. While these are critical aspects of ensuring fair practices, the additional cost burden that this would entail also needs to be taken into account. In addition, the AGPA allows for the Member countries to take up the cause of firms at the WTO Dispute Settlement Board (DSB). A very real threat to smaller economies like South Africa is the cost of litigation at the DSB. This is the more so because, unlike in domestic courts where costs can be awarded to the successful party, at that DSB there is no provision for such an award.

Cost issues aside, the largest threat for South Africa in becoming a party to the AGPA primarily arises from its low labour productivity and Total Factor Productivity.43 The low comparative advantage in manufacture44 has contributed to the fear that South African industry can be adversely affected by international competition. This is further compounded by the fact that other developing countries, like China, who are more competitive in low-value manufacturing are at an advanced stage of becoming GPA members. However, the financial thresholds of contracts below which the parties to the AGPA are not compelled to invite international price competition, provide some protection from international competition. These limits of ZAR2.1 million at national government level and ZAR3.2 million at sub-central level are sufficiently high to ensure protection for SMME firms. Moreover, the government can negotiate the exclusion of critical labour intensive sectors from the AGPA to buy time for nurturing them to face competition in the long run.

A similar threat can be perceived in relation to government procurement as a development instrument. However, as explained above, preferential procurement can very much continue at below the financial threshold and beyond the exemption list. Moreover, the money saved on procurement above the threshold can be better utilised for targetted development of sections of society and industry sectors. Studies have indicated that the scale of the contestable market estimated after the exclusions generally comes to between 10-30% of total government procurement.45 Estimated on these lines, the contestable procurement market in the case of South Africa is likely to be limited to 1-3% of GDP.

The concern for economists, of government expenditure as a fiscal policy tool can be eased by following in the footsteps of the US its "Buy American" stimulus package: USD700 billion stimulus package came with the "Buy American" clause especially for iron and steel. This has set a precedent for protectionist measures in times of economic crisis for other countries to follow. These measures could be made WTO compatible but are likely to create serious trade friction with trading partners.46

Lastly, developing countries have to actively participate in making sure that future negotiations do not turn the Agreement against them especially by invoking safety procedure and sustainability clauses.

6 WAY FORWARD

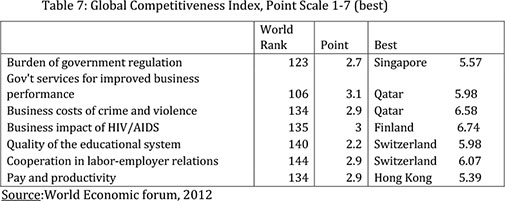

The analysis in the previous section has identified the two major emerging concerns as: (1) how can South African firms become more competitive, and; (2) how to develop an alternate and more effective procurement policy as a development tool to benefit HDIs and SMMEs. It can be argued that a firm cannot survive purely on government contracts and also that creating such dependency is not a viable proposition for the longterm sustainability of the firm. It is important to identify the reasons for the low competiveness and to take redressive measures to improve the business environment. Some of the reasons for the low competitiveness of South Africa are highlighted in Table 7.

It is obvious that the way forward in the long-term is for the government to address the fundamental issues rather than provide protection against international competition.

This will result in all-round welfare enhancement. In the interim, the government must make use of the offsets allowed under the AGPA to provide time to attain competitiveness by restricting the AGPA to sectors with low intra-industry trade. This will ensure that the AGPA does not create additional competition for sectors which are already under competitive pressure.47 Furthermore, it is in the interest of South Africa to identify labour intensive sectors for transitory exemption from the AGPA and also to put in place offsets in the form of price margins in favour of domestic firms to give the firms time to become competitive. The long-term goal of the government should be to address the structural issues and policy burdens (Table 7) that makes South African industry less competitive.

The issue of procurement policy as a development tool is a sensitive one. However, in the interest of formulating a more efficient policy for equitable development, it is essential to make an assessment of the effectiveness of the preferential procurement policy based on BBBEE. The preferential procurement policy in its current form can continue under the AGPA for contracts below the value of R2.1million and R 3.2million for goods and services in respect of national government and provincial governments respectively, so there is no reason to consider GPA as a threat to the development of HDIs or SMMEs. Instead of creating government dependency, policy should be providing with support to thrive in the economic environment through better access to finance, skills, technology, marketing and information. Given the right support through public procurement, the SMMEs can be made to be competitive and active in export markets in the long-term.48

The savings in procurement expenditure as a result of the opening up to competition of high value contracts will ensure that government can engage in more direct intervention programmes. This will benefit larger numbers of the population rather than create an elite business class at the cost of efficiency. This is likely to bring about a reduction in inequality in a more effective manner.

The conclusions emerging from the analysis is that South Africa should move towards accession to the AGPA to ensure that corruption is limited by international monitoring and competition, but that this should be a progressive and calibrated process initiated through multiple reservations to the Agreement and which are amended over time.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This article analysed the characteristics of the AGPA and the preferential procurement policy of South Africa. The conclusion reached is that government procurement is likely to result in corruption because of limited contestability and principal-agent problems.

Increased transparency and contestability are the only means to ensure better utilisation of taxpayers' money. However, an economic rationale cannot completely override social objectives and it is important to ensure that government procurement is used as a policy tool to promote local industry and poor sections of society. The clauses of the AGPA must be fully exploited to ensure that domestic industry is given the time and encouragement to become competitive internationally.

In order to ensure this, it is best that competition is phased in by stages. The first step would be for South Africa to assume observer status at the GPA, which entail no commitments, and provides an opportunity to understand and master the workings of the agreement. This has to be accompanied by increased research to obtain a better understanding of the South African public government procurement market, the competitiveness of South African firms, and the costs of compliance with the AGPA. The next phase would be to enter into negotiations regarding the threshold, sectors and offsets that would be in the national interest. The third stage would be to become a party to the AGPA with limited access provision and to use the transitory period for offsets to attain competitiveness. Stage four would be attained when South African firms can compete internationally and procurement practices are optimised.

* The author is grateful to the Mandela Institute and the School of Economic and Business Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand and; the World Trade Institute for facilitating this article. The author would like to thank Michael Power for the stimulating discussions during the conceptualisation stages of this article.

1 Audet D "Government procurement: A synthesis report" (2002) 2(3) OECD Journal on Budgeting 149. [ Links ]

2 Krugman P "Increasing returns, monopolistic competition, and international trade" (1979) 9 Journal of International Economics 469; [ Links ] Helpman E "International trade in the presence of product differentiation, economies of scale, and monopolistic competition: A Chamberlin-Heckscher-Ohlin approach" (1981) 11 Journal of International Economics 305. [ Links ]

3 Melitz J M "The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity" (2003) 71 Econometrica 1695; [ Links ] Antras P & Helpman E "Global sourcing" (2004) 112 Journal of Political Economy 552. [ Links ]

4 Schooner S L & Yukins CR "Public procurement: Focus on people, value for money and systemic integrity, not protectionism" in Baldwin R & Evenett S (eds), The collapse of global trade, murky protectionism, and the crisis: Recommendations for the G-20, (VoxEU.org eBooks 2009) at 87-92. [ Links ]

5 Evenett S & Hoekman B "Government procurement: Market access, transparency, and multilateral trade rules"(2005) 21(1) European Journal of Political Economy 163. [ Links ]

6 Martin S The theory of contestable markets (2000). Available at http://www.krannert.purdue.edu/faculty/smartin/aie2/contestbk.pdf (accessed 21 May 2014).

7 Baumol J W & Willig R D "Contestability: Developments since the book" (1986)38 Oxford Economic papers, New Series; Supplement: Strategic Behaviour and Industrial Competition at 9. [ Links ]

8 Evenett J S & Hoekman B International disciplines on government procurement: A review of economic Analyses and their Implications (2004). Available at https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/export/.../Simon_Evenett/22321.pdf (accessed 21 May 2014). [ Links ]

9 Trionfetti F "Discriminatory public procurement and international trade" (2000) 23 World Economy 57.

10 See Evenett & Hoekman (2005) at 163.

11 McAfee RP & McMillan J "Government procurement and international trade" (1989) 26 Journal of International Economics 291. [ Links ]

12 UNCTAD Competition Policy and Public Procurement : Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Competition Law and Policy, 12th Session, Note by the UNCTAD secretariat, (Geneva: UNCTAD 2012) at 3. [ Links ]

13 Bardhan PK "Corruption and development: A review of issues" (1997) 35 Journal of Economic Literature 1320; [ Links ] Rose-Ackerman S Corruption and government: Causes, consequences and reform (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999). [ Links ]

14 Shingal A Estimating market access in non-GPA countries: A suggested methodology, World Trade Institute Working Paper No 2012/06 (2012). Available at http://www.wti.org/fileadmin/user_upload/nccr-trade.ch/wp6/publications/wp2012_6%20SHINGAL%20Estimating%20market%20acces2.pdf (accessed 21 May 2014). [ Links ]

15 The functional classification of cash payments measures the purposes for which transactions are undertaken.

16 Source: Estimated from P9121, P9119.3, P9119.4 StatsSA (2011) Rest includes municipalities, higher education institutions and extra budgetary accounts and funds. GF code 22+611.

17 Pauw JC & Wolvaardt JS "Multi-criteria decision analysis in public procurement- a plan from the South" (2009) 28 (1) Politeia 66. [ Links ]

18 Bolton P "Government procurement as a policy tool in South Africa" (2006) 6 (3) Journal of Public Procurement 193. [ Links ]

19 Act 5 of 2000.

20 At present this entails that all tenders over R30000 must be subject to the points system, with contracts up to R1million using the 80/20 system and contracts above 1million using the 90/10system. This means that contract is awarded to the tenderer obtaining highest points where the 20 points in first category and 10 points in the second category are provided on the basis of the broad-based Black economic empowerment status of the firm.

21 According to the Preferential Procurement Regulations 2001, a HDI is defined as meaning: "a South African citizen who, due to the apartheid policy that had been in place, had no franchise in national elections prior to the introduction of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1983 (Act 110 of 1983) or the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1993 (Act 200of 1993); and/or who is a female; and/or who has a disability, provided that a person who obtained South African citizenship on or after the coming into effect of the interim Constitution, is deemed not to be an HDI."

22 Government Gazette No. 16085 of 23 November 1994.

23 Preferencial Procurement Regulations 4(2) and 6(5).

24 Section 2(1)(f) of the PPPFA.

25 Section 2(1)(e) of the PPPFA.

26 Section 3of the PPPFA.

27 Office of the Audit-General of South Africa, General report on national audit outcomes 2010-11 (2012). Available at http://www.agsa.co.za/Reports%20Documents/AGSA%20NATIONAL%20CONS%20OUTCOMES%202011_1to80.pdf (accessed 10 September 2012).

28 The meaning of "objective criteria" has been the subject of many court cases. The primary issue has been the meaning to be afforded to the phrase 'objective criteria in addition to those contemplated in PPPFA paragraphs (d) and (e)'. In the absence of any widely accepted definition of "objective criteria" it is submitted that the courts will determine these on a casuistic basis. The jury is therefore still out on the meaning of "objective criteria."

29 PPPFA para 2 (1)(d) provides:

'(d) specific goals may include- (i) contracting with persons, or categories of persons, historically disadvantaged by unfair discrimination on the basis of race, gender or disability; (ii) implementing the programmes of the Reconstruction and Development Programme as published in the Government Gazette No 16085 dated 23 November 1994; (e) Any specific goal for which a point may be awarded, must be clearly specified in the invitation to tender.'

30 OECD Collusion and Corruption in Public Procurement, Global Forum on Competition (2010) at 350. Available at http://www.oecd.org/competition/cartels/46235884.pdf [accessed 5 August 2012]

31 ILO Targeted procurement in the Republic of South Africa: An independent assessment (April 2002). Available at http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_policy/---invest/documents/publication/wcms_asist_8369.pdf (accessed 5 August 2012).

32 World Bank South Africa- Country procurement assessment report: Refining the public procurement system (2003 World Bank Report No. 25751). Available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2003/02/2259443/south-africa-country-procurement-assessment-report-refining-public-procurement-system-vol-2-2-main-text (accessed 5 August 2012).

33 World Bank World development indicators: Electronic database (2012). Available at http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators [accessed 5 August 2012]

34 Ntshona S Access to markets, unpacking opportunities for SMMEs (Presentation at the Conference on SME Africa 2012, 17-18 October 2012, Johannesburg).

35 Luiz J "Small business development, entrepreneurship and expanding the business sector in a developing economy: The case of South Africa" (2003)18 (2) Journal of Applied Business Research 53.

36 WTO General overview of WTO Work on Government Procurement (2012). Available at http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/gproc_e/overview_e.htm (accessed 21 May 2014).

37 Arrowsmith S & Anderson R (eds) The WTO regime on government procurement: Challenge and reform, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2011) at 18.

38 Nooteboom E The Opening of Government Procurement in the EU and in a Global Context (Presentation given at LIMA, 14 October 2010 by Head International Dimension of Public Procurement, European Commission, file at http://www.osce.gob.pe/consucode/userfiles/image/III%20-%20Erik%20Nooteboom%20-%20Comision%20Europea.pdf (accessed 10 Septermber 2012).

39 See World Bank, above n 31, at 13.

40 Heimler A "Cartel in Public Procurement" 2012, Journal of Competition Law and Economics, at 1. doi:10.1093/joclec/nhs028.

41 World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness report 2012-13 2012.(File found at http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2012-13.pdf (accessed 5 August 2012).

42 Global Competition Review. Available at http://www.globalcompetitionreview.com/news/article/29705/gcr-2011-award-winners-announced/2011 (accessed 5 August 2012).

43 Edwards L & Golub S "South African productivity and capital accumulation in manufacturing: An international comparative" (2003)71 (4) South African Journal of Economics 659.

44 Fourie J "Travel service exports as comparative advantage in South Africa" (2011)14 (2) South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 210.

45 See Shingal (2012) at 5.

46 Burns N & Price J The global economic Crisis (Washington D.C.: The Aspen Institute 2010) at 24.

47 Kim DH "Intra-industry trade and protectionism: the case of the buy national policy" (2010)143 Public Choice 49.

48 ITC SME and export-led growth: Are there roles for public procurement programmes? A practical guide for assessing and developing public procurement programmes to Assist SMEs (2003). Available at http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/gproc_e/wkshop_tanz_jan03/itcdemo3_e.pdf (accessed 5 September 2012).