Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.18 Cape Town 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v18i1.8

Before the camel's back is broken: How Malawi provides succour to employers by jettisoning the payment of a severance allowance and pension benefits at the same time

Mtendeweka Mhango

Associate Professor and Deputy Head, University of the Witwatersrand, School of Law, Johannesburg

1 INTRODUCTION

After the enactment of the Employment1 (the Employment Act), the legal position in Malawi was that an employee, who left the employment of the employer (for reasons other than his own resignation or misconduct) that had provided voluntary contractual pension benefits, was entitled to payment of both pension benefits and a severance allowance. The employer was liable for these payments. Hence, there was a double burden on the employers, who operated voluntary pension schemes for their employees, to statutorily pay severance allowances and contractually pay pension benefits upon the termination of employment.2 It is important to mention that prior to 2011 the provision of pension benefits was not mandatory in Malawi but voluntarily provided for by some employers in their employment contracts. Hence, I refer to voluntary contractual pension benefits to distinguish them from the current mandatory pension benefits entitlement under the Pension3 (the Pensions Act). There were numerous legal challenges by employers against this double financial burden, but the courts, including the Supreme Court of Appeal in Auction Holdings,4 consistently held that employees are entitled to be paid both a severance allowance and pension benefits upon termination of their employment by the employer, and that the employer is liable to pay these costs.5

This article discusses the problems surrounding the payment of a severance allowance and private pension benefits in Malawi. It starts by discussing the case law developments following the passage of the Employment Act and its subsequent amendments, which were repeatedly struck down by the courts. The article seeks to demonstrate the context which led to major pension and employment reforms in 2011 in the form of the Pension Act and the Employment Amendment6 (the Employment Amendment Act), which were concurrently enacted to specifically resolve the above problem. It examines the effects of these legislative reforms on Auction Holdings and later cases, and whether these legislative reforms undermined those judicial pronouncements.

The article argues that the legal position that prevailed after 2000, when the Employment Act was enacted, no longer exists following the enactment of the Pension Act and the Employment Amendment Act. Further, it argues that Auction Holdings and its preceding cases are no longer good law at least on one legal proposition because the Pension Act and Employment Amendment Act undermined some aspect of Auction Holdings.

2 THE GENESIS OF THE SEVERANCE ALLOWANCE IN MALAWI

In 2000, the legislature in Malawi enacted the Employment Act to regulate employment relations in the country. Among the aspects of employment relations that the Employment Act sought to regulate was an employee's entitlement to the payment of, among other things, a severance allowance following the termination of employment.

Generally, severance allowance is understood to be money that is paid by an employer to an employee who leaves the services of the employer for any reason other than just cause. Commentators and jurists describe severance as

[A] form of compensation for the termination of the employment relationship, for reasons other than the displaced employees' misconduct, primarily to alleviate the consequent need for economic readjustment but also to recompense him for certain losses attributable to the dismissal.7

Among the policy objectives of a severance allowance is "the necessity of developing new skills and the readjusting of the employee's life to altered circumstances and contribution to the maintenance of the good will of employees and the community generally."8 In the Malawian context, Chilumpha has poignantly explained that:

Severance allowance is compensation to an employee for the termination of his employment by the employer on grounds other than his misconduct, to facilitate his re-adjustment to the resulting loss of income. As this definition shows, once an employee is dismissed or his employment is otherwise brought to an end he is faced with immediate loss of income and benefits available to him. For that reason unless he is able to quickly get another job or stable source of income, he can easily descend into a very serious state of destitution. And the problem is compounded by the fact that there is no social security provision in this country. To minimise the impact of that problem, the Employment Act prescribes some minimum payment to an employee who loses his employment through unfair dismissal or such other causes as the death or insolvency of his employer. Consequently, the payment is a form of minimum social security provision.9

The relevant provision in the Employment Act which regulates severance allowances, is section 35. Prior to 2011, this section provided, in pertinent parts, as follows:

35.(1) On termination of contract, by mutual agreement with the employer or unilaterally by the employer, an employee shall be entitled to be paid by the employer, at the time of termination, a severance allowance to be calculated in accordance with the First Schedule.

(2) The Minister may, in consultation with organizations of employers and organizations of employees, by notice published in the Gazette, amend the First Schedule.

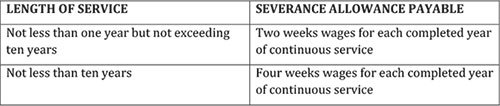

The First Schedule referred to in section 35, provided that a severance allowance shall be calculated as follows:

From its enactment, section 35 presented a major challenge to employers who operated voluntary pension schemes. The dilemma was that these employers had a double financial burden: to pay a severance allowance as well as pension benefits upon termination of an employees' employment. In most reported and unreported cases, the general defence advanced by employers against claims for a severance allowance was that a severance allowance was not payable where the employee was paid pension benefits for the same period of employment. As will be demonstrated later, the courts consistently rejected these and other related arguments in favour of the legal proposition that the employee was entitled to be paid both pension benefits and a severance allowance upon termination of employment. Due to the gravity of the dilemma faced by employers, the executive branch took some steps to resolve it.

3 EXECUTIVE ATTEMPTS TO ADDRESS THE SEVERANCE ALLOWANCE DILEMMA THROUGH SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION

Before discussing the cases that illustrate the problems surrounding the entitlement to and payment of a severance allowance, it is important to point out that on two occasions the executive branch attempted to resolve the problem by amending section 35 of the Employment Act. The first attempt was in January 2002. In that year, the Minister of Labour and Vocational Training revoked the First Schedule and replaced it with a new Schedule by the Employment Act (First Schedule) Amendment Order 2002 (Order of 2002). The Order of 2002 made two important changes to the existing regulation. First, it introduced a new formula for calculating a severance allowance.10 Secondly, it incorporated circumstances where no severance allowance would be payable, such as where an employee was entitled to pension, gratuity and other terminal benefits, which exceeded the severance allowance payable in terms of the new formula introduced by the Order of 2002.

Following the promulgation of the Order of 2002, the Minister of Labour and Vocational Training was challenged in Khawela.11 Before invalidating the Order of 2002, Judge Potani made a few preliminary observations. He noted that section 35(1) governs an employees' entitlement to a severance allowance while section 35 (2) governs the mechanism for calculating the severance allowance payable. Potani J also noted that "the power the Minister has is only to amend the formula or mechanism for calculating severance allowance."12 However, it was noted that the "effect of the Order of 2002 is to forfeit payment of severance allowance to employees who are entitled to payment of pension, gratuity or other terminal benefit."13 According to Potani J, "the Minister was not empowered to amend the conditions that would entitle one to payment of severance allowance because these were already provided for in subsection (1) of section 35." Turning to the specific problem at hand, Potani J reasoned that:

It appears the driving force behind the Minister's decision was to avoid a situation in which an employee whose contract has been terminated would get double payment, that is, pension or gratuity or other terminal benefits on the one hand and also severance pay on the other hand. The problem the Minister sought to address mainly comes about because the Employment Act in its entirety does not define severance pay. Thus, much as the Minister's intention might perfectly be right on economic and moral considerations, the decision made by the Minister exceeded the power conferred by the law. ... The Minister sought to do something which is morally and economically right through the back door. This is a Court of law not one of morality.14

In the end, Potani J held that "the Minister acted in excess of the powers conferred by section 35 of the Employment Act and indeed section 58(1) of the Constitution and thus the Order of 2002 is invalid and quashed".15 Before Potani J's ruling was delivered on 5 November 2004, the Minister of Labour and Vocation Training (with full knowledge of the impending ruling) promulgated another amendment to section 35 of the Employment Act by the Employment Act (First Schedule)(Amendment) Order 2004 (Order of 2004) on 3 February 2004. The Order of 2004 was declared invalid for the same reasons applicable to the Order of 2002.16

4 SEVERANCE ALLOWANCE JURISPRUDENCE

There are a number of cases that illustrate the extent of the problem of the double financial burden on employers and how it affected employees in Malawi. I discuss a few of these cases below.

4.1 The Thomson case

One of the first cases that dealt with the above problem was Thomson. In this case, the plaintiff was employed by the employer from 1970 to 2003. In late 2002, the plaintiff withdrew from membership of the pension scheme operated by the employer and was paid a withdrawal benefit of K649,519.97. The plaintiff sued the employer on the grounds that the employer refused or failed to pay him a severance allowance for the 30 years of continuous service he had rendered to the employer. The employer defended the case and argued that the plaintiff was not entitled to a severance allowance on the basis that he was paid pension benefits for the same period of employment, which exceeded the severance allowance that would have been paid to him. In other words, the employer's view was that the plaintiff was only entitled to the greater amount of either the pension benefits or the severance allowance.

In deciding whether the plaintiff was entitled to payment of a severance allowance, the Court in Thomson observed that both parties based their arguments on the Order of 2004, which it noted was invalidated in Khawela.17 Therefore, the Court reasoned that the position in law is that a severance allowance is still payable in the circumstance of this case, and that nothing stops a court from awarding a severance allowance. In addition, the Court reasoned that it was clear from the provisions of the Employment Act that the legislature has not said that a severance allowance would not be paid where an employee's pension benefits exceeded the severance allowance. As a result, the Court concluded that the plaintiff was entitled to a severance allowance.

4.2 The Mwalwanda case

Another important case that dealt with the issues of pension benefits and severance allowance is Mwalwanda v Stanbic Bank Limited.18 In this case, the plaintiff was employed by Stanbic Bank for 24 years. As a consequence of his employment, he became a member of Stanbic's pension scheme. Plaintiff went on early retirement, which in terms of the rules of the pension scheme, had to be approved by Stanbic Bank. At the time of this case, the plaintiff was receiving monthly pension benefits. A dispute arose when plaintiff demanded that he be paid his severance allowance under the Employment Act. Stanbic Bank denied that plaintiff was entitled to a severance allowance. The plaintiff commenced this action claiming severance allowance.

In defence, Stanbic Bank commenced an application to dispose of plaintiff's action on a point of law pursuant to Order 14A of the Rules of the Supreme Court, and sought the court's determination of a number of questions of which the most important were:

3. Whether the decision of Potani J in The State vs The Attorney General (Minister of Labour & Vocational Training ex parte Mary Khawela & Others) Misc Civil Cause No 7 of 2004 reverses all acts lawfully done under the Employment Act (First Schedule) (Amendment) Order 2002 during the 2 years it was in force?

4. Whether the defendant is liable to pay the plaintiff severance allowance which was not payable to the plaintiff in accordance with the provisions of the Employment Act (First Schedule) Amendment Order 2002 which was in force at the time the plaintiff's employment was terminated by way of early retirement at his instance?

...

6. Whether the provisions of the Employment Act No 6 of 2000 have retrospective application by conferring benefits on employees and creating new obligations for employees for the years when the said Act was not in force?

The parties agreed that the responses to these questions would dispose of the matter. The Court decided to deal with questions three and four together because both questions related to whether under the Employment Act there is a legal basis for the plaintiff to receive a severance allowance from Stanbic Bank. The Court reasoned that since the Order of 2002 was declared invalid in Khawela, it followed that whatever was done under it was of no legal effect regardless of how many times it was done. Additionally, the Court, citing the judgment in Press Produce Limited v AHB Enterprises,19 concluded that the answer to questions three and four must be decided in the affirmative.

Lastly, in relation to question six, whether the Employment Act has retrospective effect, the Court ruled that the legislative intent in the Employment Act was to make section 35 apply retrospectively. The Court's reasoning for this decision was borrowed from Japan International Cooperation Agency v Verity Jere20 where Nyirenda J reasoned that:

Section 35(1) in effect compels employers to recognize the commitment and valuable contribution which employees make to the work they do. Clearly the provision protects employees from being told to go with one month's pay after working for an employer for a considerable number of years. In the spirit of Section 31(1) of the Constitution, Section 35(1) of the Employment Act 2000 is meant to protect employees who have long served their masters and puts a stop to exploitation. It is in this spirit that in my judgment, Section 35(1) was meant to take on board all the committed employees and all that they have toiled for in the years past and present... the case for retrospective application of Section 35(1) is made clear by looking at the wording of Section 63(4) and 63(5) [Employment Act] which refers to past employment in using the expression an employee who has served on the compensation formulae. To this extent I am of the clear view that Section 35 of the Employment Act 2000 must operate retrospectively and reward those that have been faithful to their employers.

Based on the above, the court ruled that "as it stands at the moment I agree with the reasoning of Nyirenda J in Japan International Cooperation Agency vs Jere and his conclusion that section 35(1) has retrospective operation."21 The Court's decision in Mwalwanda v Stanbic Bank Limited was taken on appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court upheld the lower court's decision and said the following:

To hold that the First Schedule as amended by the Minister in 2004 was valid and applicable to the facts of this case would be tantamount to legitimizing a clear usurpation by the Minister of the powers of Parliament. That would also be a contravention of the principle of the rule of law. We agree that what the Minister did in both 2002 and 2004 concerning the amendment of the 1st Schedule, as null and void ab initio and the appellant cannot rely or derive and benefit from such invalid amendment.22

Following the Supreme Court's endorsement of the High Court decision it became clear that the dilemma concerning entitlement to and payment of a severance allowance had reached a highpoint.

5 THE HIGHPOINT OF THE SEVERANCE ALLOWANCE DILEMMA

The legal pronouncements reflected in the above cases were consistently applied in subsequent cases,23 and there are two highpoints in these legal developments concerning whether an employer is obligated to pay both pension benefits and a severance allowance. The first highpoint arose when the Supreme Court decided Auction Holdings in 2008. The second highpoint point occurred when the Pension Act and Employment Amendment Act were enacted in 2011. I will discuss these highpoints in turn.

5.1 Auction Holdings and its effects

In Auction Holdings, the appellant retrenched its employees and paid them either pension benefits or severance allowances. Each employee received whichever was the greater amount. The employees were not happy with the manner in which these benefits were calculated, and brought an action in the Industrial Relations Court (IRC) which ruled that "it was permissible for an employee to be paid which ever was higher between pension and severance allowance."24 The employees appealed to the High Court. The High Court, consistent with the ruling by Potani J in Khwawela held that the employees were entitled to be paid both severance allowances and pension benefits upon termination of their employment. The appellant appealed to the Supreme Court. Six grounds of appeal were raised, but for present purposes only two grounds will be dealt with.

The first ground of appeal was the issue of whether the ruling of Potani J in Khawela, which invalidated the Order of 2002, had retrospective effect. The appellant's contention was that the declaration of invalidity takes effect prospectively. The Supreme Court disagreed and ruled that the order of invalidity by Potani J had retrospective effect. The Court cited English authorities which consider any "enactment which has been declared invalid by a court on the ground that it was ultra vires, as nullity ab initio and of no effect."25 Additionally, the Supreme Court reasoned that English authorities were consistent with the position the Supreme Court took in Mwalwanda.

The second ground of appeal was an attempt by the appellant to defend the actions of the Minister in enacting Order of 2002. The Supreme Court dismissed the appellant's argument, and noted that the legality of Order of 2002 had been exhaustively and finally dealt with by High Courts and the Supreme Court. The Court affirmed Potani J's ruling and pointed out that a number of other High Court judges had no difficulty in agreeing with Potani J as well.

On the question of whether to pay both pension benefits and a severance allowance, the Supreme Court reasoned that it was trite law that "both pension, where it is separately provided in a private agreement, and severance allowance are payable upon the occurrence of certain events."26 The Supreme Court went further and reasoned that "section 35 of the Employment Act is only concerned with severance allowance and not pension or gratuity because the latter is a matter of private agreement between the employer and employee, whereas the former is a statutory imposition."27 To further explain the difference between pension and severance allowance, the Supreme Court cited with approval the reasoning in the case of Chimpeni where Kamwambe J stated:

The import from Section 35 (1) is that severance allowance is not negotiable, it is not necessarily contractual as it will exist whether or not it is included in the conditions of employment. It is a statutory entitlement, parties can choose to provide or not provide for pension or gratuity in their employment contract. This is why pension is a different animal from severance allowance.28

The decision in Auction Holdings was a highpoint because it definitely laid to rest the legal battles between employers and employees in Malawi over the question of whether or not an employer was obligated to pay both pension benefits and a severance allowance upon termination of employment. The decision in Auction Holdings confirmed that the employer was obligated to pay, and made it clear that it was not prepared to reverse its ruling on the matter. In other words, Auction Holdings confirmed that the dilemma faced by employers and employees was legally permissible. For most employees and employers the problem required a political solution.

Following Auction Holdings, a number of employers effected amendments to pension fund rules to make provision for the payment of a severance allowance using the employer's pension contributions.29 Most of these rule amendments granted the employer permission to apply its pension contributions to the fund to meet the severance allowance obligation in the event of termination of employment. Furthermore, these amendments provided that whenever the employer had a statutory liability to pay an employee, such employer could call on the pension fund to release the employer's pension contributions for account of that employee to meet the statutory liability. It was envisioned that the balance of the funds would be used towards the purchase of a pension annuity for the employee.

It is important to mention that the above rule amendments were adopted by employers as a last effort to alleviate the double financial burden faced by them in Malawi over the payment of a severance allowance. The legal theory behind these rule amendments was that since section 35 of the Employment Act was silent about the source of the severance allowance, it was deemed legally permissible to use the pension contributions by the employer to fund the severance allowance obligation. The effect of these rule amendments was that the employer would not face the double financial burden to pay both the pension benefits and the severance allowance.

In Mphande v FDH Bank30 (Mphande), the IRC had to consider whether these rule amendments were lawful. In that case the plaintiff was an employee, who after her employment was terminated, was entitled to both pension benefits and a severance allowance. The employer agreed to this entitlement. However, it used the employer's pension contribution to the fund to meet the severance obligation as per the rules of the pension fund described above. The IRC, citing Chimpeni and Auction Holdings, held that it was improper for an employer to discharge its severance allowance payment obligation from any pension fund contributions. The IRC reasoned that Chimpeni and Auction Holdings supported the view that "it would be wrong to deduct severance allowance for purposes of meeting some contractual obligations."31 The IRC further reasoned that "for an employer to put up a mechanism whereby they use pension contributions to satisfy the need of severance allowance is to flout the law by the back door."32 In the end, the employer was ordered not to utilise its pension contribution to meet the employee's severance allowance expectation. This case leads me into the discussion of the second tipping point.

5.2 The enactment of the Pension Act and Employment Amendment Act

In 2011, the legislature in Malawi passed the Pension Act and the Employment Amendment Act concurrently to specifically resolve the above problem. Unlike before, pension entitlement is now governed by the Pension Act, while severance allowance entitlement continues to be governed by the Employment Act as amended. Under these reforms, the circumstances under which a pension entitlement or a severance allowance is applicable are distinct. A severance allowance is no longer payable on the retirement or death or incapacitation of the employee as was previously the case.33 Instead, benefit entitlement arising from retirement, death or incapacitation is now governed by the Pension Act.34 a severance allowance is now only payable in specific instances as provided in section 2 of the Employment Act as amended, which reads as follows:

On the termination of a contract as a result of redundancy or retrenchment, or due to economic difficulties, technical, structural or operational requirements of the employer, or the unfair dismissal of an employee by the employer and not in any other circumstance, an employee shall be entitled to be paid by the employer, at the time of termination, a severance allowance to be calculated in accordance with Part I of the First Schedule.

Since the Pension Act and the Employment Amendment Act were passed concurrently to resolve, among other things, a specific dilemma, the two Acts are expected to be implemented together. The connection between the Pension Act and the Employment Act, as amended is made clear in section 91 of the Pension Act, which deals with the transitional arrangements. Section 91 provides, in pertinent part:

(1) Every employer shall recognize as part of an employee's pension dues, each employee's severance due entitlement accrued from the date of employment of that employee to the date of commencement of this Act.

(2) For employers not providing pension or gratuity prior to the date of commencement of this Act, the severance entitlement referred to in subsection (1) shall be calculated in accordance with the provisions of the Employment Act.

(3) For employers providing pension or gratuity prior to the date of commencement of this Act, the severance entitlement referred to in subsection (1) shall be calculated as having a value equal to the value of

(a) the severance entitlement calculated in accordance with the provisions of the Employment Act;

(b) less the sum of the accumulated employer pension contributions made or gratuity paid prior to the date of commencement of this Act and any growth on such contribution.

(4) The severance entitlement as calculated in subsection (2) and subsection (3) shall... be transferred into a pension fund of the employees choice within a period not exceeding eight years after the commencement of this Act.

To fully appreciate the significance of the connectedness of these reforms, it is critical to comprehend the objectives of and framework under the Pension Act. Section 4 of the Pension Act delineates its objectives, which are to:

(a) ensure that every employer to which this Act applies provides pension for every person employed by that employer;

(b) ensure that every employee in Malawi receives retirement and supplementary benefits as and when due;

(c) promote the safety, soundness and prudent management of pension funds that provide retirement and death benefits to members and beneficiaries; and

(d) foster agglomeration of national savings in support of economic growth and development of the country.

The Pension Act represents a major shift in the regulation of pension funds in Malawi. The primary purpose of the Pension Act is to ensure that an employer to which this Act applies provides a pension for every person employed by that employer. To achieve this policy objective, section 6 stipulates that:

(1) There is hereby established a contributory National Pension Scheme (in this Act otherwise referred to as the "National Pension Scheme") for the purpose of ensuring that every employee in Malawi receives pension and supplementary benefits on retirement.

(2) The National Pension Scheme shall comprise-

(a) a national pension fund to be established under this Act, by the Minister, by Order published In the Gazette; and

(b) other pension funds licensed under this Act.

(3) Every employer shall male provision for every person under this employment to be a member of the National Pension Scheme.

The above section should be read together with section 9, which provides as follows:

(1) Subject to section 10, every employer shall make provision for every person under his employment to be a member of the National Pension Scheme.

(2) The Minister responsible for labour and the Registrar, in consultation with the Minister, shall be responsible for ensuring compliance with this part.

(3) Any employer who, without reasonable excuse, fails to comply with this section, shall be liable to administrative penalties under the Financial Services Act, 2010.

Based on the above provisions, the employer is required to facilitate employees' membership of the national pension scheme. This requires that an employer must ensure that his employee becomes a member of either the national pension fund (which covers all civil servants) or any other registered pension fund.35 Further, as discussed in detail below, once an employee becomes a member of the national pension scheme, the Pension Act defines the minimum pension contributions that he and his employer must pay into the scheme. According to section 12(1), the employer and employee are required to contribute 10 and 5 per cent of the employee's salary, respectively, to the pension fund.

However, the Pension Act is not applicable to every employer or employee. Section 10 governs the scope of the Pension Act, and prescribes exemption requirements. It confers a discretion on the Minister of Finance, in consultation with the Minister of Labour and the Registrar of Financial Institutions (Registrar),36 to prescribe, by order in the Government Gazette, a salary threshold which will exempt an employer or employee from complying with the requirements of sections 9 and 15 of the Pension Act. Section 10 of the Pension Act has to be read together with section 6(3) of the Employment Amendment Act. The latter provision provides that "an employer whose employee's monthly salary is below ten thousand kwacha may be exempted from complying with the provisions of the Pension Act".37

In 2011, the Minister of Finance promulgated the Pension (Salary Threshold and Exemptions) Order 2011 (Pension Order 2011) pursuant to section 10 of the Pension Act.38 The Pension Order 2011 is significant because, first, it exempts certain employers from complying with certain provisions of the Pension Act. Section 3 of Pension Order 2011 stipulates that "an employer whose employees' monthly pension emoluments is ten thousand kwacha or less, shall be exempt from complying with the requirements of sections 9 and 15 of the Act." Secondly, Pension Order 2011 exempts a class or category of employees and employers from the Pension Act. Section 4 exempts seasonal workers,39 tenants,40 expatriates in possession of a temporary employment permit,41 members of parliament in their capacity as such, and domestic workers from complying with the provisions of the Pension Act.

While the objective of Pension Order 2011 is to determine the exemption of an employer and/or employee from the Pension Act, there are two important exceptions. The first exception is contained in section 10(2)(a) of the Pension Act, which provides that where an employer employs five employees or more, that employer must provide a pension for those employed regardless of whether their salaries fall below the prescribed salary threshold.

The second exception is contained in section 10(2)(b) of the Pension Act and provides that any employer, who has an existing pension scheme at the commencement of the Pension Act, will be required to ensure that every employee who was a member of such pension scheme continues to be a member regardless of the salary threshold. It is clear that these exceptions to Pension Order 2011 are designed to ensure that more employees in Malawi are covered by the pension legislation in accordance with the objectives of the Pension Act.42

One of the significant effects of the Pension Act and the Employment Amendment Act is that they resolved the pension benefits and severance allowance problem discussed above by overruling the Supreme Court decision in Auction Holdings. Employees are no longer entitled to both pension benefits and a severance allowance following the termination of employment, as was pronounced in that case. Legislation now governs the specific instances when an employee would be entitled to pension benefits or a severance allowance. Moreover, entitlement to pension benefits is no longer a matter of private agreement between the employer and employee, as ruled by the Supreme Court in Auction Holdings. Instead, both pension benefits and severance allowance entitlements are now governed by statute albeit in well defined circumstances.

6 CONCLUSION

The enactment of the Pension Act and Employment Amendment Act marked the end of the series of legal battles to resolve the double financial burden faced by employers in Malawi in relation to the payment of pension benefits and a severance allowance to employees. Following these reforms, Malawi was not only able to resolve the above problems, but address the widespread income insecurity on retirement faced by a majority of working Malawians.43 Presently, the legislation clearly prescribes the instances where the employee is entitled to either a severance allowance or pension benefits or both. As a general rule, employers no longer have the double financial burden, that prevailed between 2000 and 2011, to pay both pension benefits and a severance allowance. The challenge that remains in Malawi is now to ensure the full implementation of these pension and employment reforms.

1 Act 6 of 2000.

2 Chilumpha C Unfair dismissal: underlying principles and remedies (Limbe, Malawi: Commercial Law Centre 2007) at 453. [ Links ]

3 Act 6 of 2011.

4 Auction Holdings Ltd v Kabvala & others 2008 (48) MSCA Civil Appeal (Auction Holdings).

5 See The State v Attorney General ex-parte Khawela & others 2004 (Appeal No 7) (unreported) (Khawela), holding that the respondents were entitled to be paid both a severance allowance and pension benefits upon termination of their employment; Chimpeni & others v Chibuku Products 2002 (Civil Cause No. 3225), (unreported), agreeing with Khawela; Stanbic Bank Limited v Mwalwanda 2007 (18) MWHC 18 (Mwalwanda); E. K. Thomson v Leyland DAF (Malawi) Ltd 2004 (63) MWHC (Thomson); International Cooperation Agency v Verity Jere 2002 (Civil Appeal No 25 ) (unreported).

6 Act 27 of 2011.

7 Earthman JB "Illusory protection: The treatment of severance packages in business bankruptcies" (2002) 5 University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment Law 33 at 36; [ Links ] Adams v Jersey Central. Power & Light Co., 120 A.2d 737 (N.J. 1956) at 740.

8 Adams v Jersey Central Power & Light Co. 740-741; Owens v. Press Publishing Co., 120 A.2d 442, 445 (N.J. 1947); Guiliano v Cleo, Inc., 995 S.W.2d 88 (Tenn. 1999) at 97, opining that "the reason for severance pay is to offset the employee's monetary losses attributable to the dismissal from employment and to recompense the employee for any period of time when he or she is out of work".

9 Chilumpha (2007) at 453.

10 Mwalwanda at 3.

11 Khawela at 3.

12 Khawela at 18.

13 Khawela at 18.

14 Khawela at 18-19.

15 Khawela at 19.

16 Thomson at 3, where Kapanda J found that to the extent that the Order of 2004 repeats the invalid Order of 2002, and to the extent that it introduces matters that are ultra vires s 35 of the Employment Act, it (the Order of 2004) must also be invalid.

17 Khawela at 3.

18 Mwalwanda at 3.

19 Press Produce Limited v AHB Enterprises [1987] 12 (1) MLR.

20 Japan International Cooperation Agency v Verity Jere 2002 (Civil Appeal No 25 ).

21 Mwalwanda 2007 (18) MWHC at 3.

22 Mwalwanda v Stanbic Bank Limited MSCA Civil Appeal No 22 (2007).

23 Zamaere v SUCOMA Ltd 2001(IRCM Matter no 157); Kapolo v Securicor (Mw) Ltd 2001 (IRCM Matter no 152).

24 Auction Holdings at 2.

25 Auction Holdings at 5.

26 Auction Holdings at 13.

27 Auction Holdings at 13.

28 Auction Holdings at 14, citing Chimpeni & others v. Chibuku Products 2002 (Civil Cause No. 3225).

29 See, Mphande v FDH Ltd 2011 (5)MWIRC; Kalolokesya & another v Beit Cure International Hospital [2010] MIRC 23; and 'Court Thwarts Employers Stand On Pensions' 16 November 2011. Available at http://www.nyasatimes.com/2011/11/16/court-thwarts-employers-stand-on-pensions/ (accessed 18 October 2014).

30 Mphande v FDH Ltd 2011 (5) MWIRC.

31 Mphande at 7.

32 Mphande at 7.

33 See s 35 of the Employment Act.

34 Pension Act, ss 15, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 70, 71 and 72.

35 See s 6(2) of the Pension Act. According to a recent decision by the Registrar, all existing pension schemes are deemed registered under the Pension Act. See The Nation Press Release (15 August 2011) at 36. See also s 8 of the Taxation (Amendment) Bill No 2 of 2012 which provides that "any pension fund approved by the Commissioner of Taxes shall be deemed to have been registered under the Pension Act."

36 The Registrar was established under s 8 of the Financial Services Act 2010 with the primary objective to regulate and supervise the financial services industry, which includes pension funds.

37 Employment (Amendment) Act, First Schedule, Part II, para 3. See also ss 10 and 9 of the Pension Act.

38 GN 32 of 2011.

39 "Seasonal workers" means "employees whose work, because of its nature or because of factors peculiar to the industry in which it is performed, is available, at approximately the same time or times every year, for part or parts of the years" See s 2 of Pension Order 2011.

40 Tenant means an employee in terms of the Employment Act, "who enters the services of a landlord to grow a crop of the landlord or any other related services." See s 2 of Pension Order 2011.

41 "Expatriates" means "skilled professionals of foreign origin working in Malawi and holding a valid temporary employment permit issued by the relevant authorities in Malawi." See s 2 of Pension Order 2011.

42 See s 86(3) of the Pension Act, which exempts any employee, who from the date that Act became enforceable was entitled to pension benefits and has three or less years until retirement date, from complying with the Pension Act.

43 See Mhango M "Pension regulation in Malawi: defined benefit fund or defined contribution fund?" (2012) 17 (4) Pensions: An International Journal 270. [ Links ]