Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907

Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.18 Cape Town 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v18i1.4

Driving corporate social responsibility through Black economic empowerment

Henk Kloppers

Senior Lecturer, North-West University (Potchefstroom campus)

1 INTRODUCTION

Motivated by the imperative to redress the imbalances caused by economic exclusion, government has taken remedial measures and established a framework aimed at empowering Black1 South Africans.2 Government's commitment to empowering previously disadvantaged South Africans and achieving socio-economic transformation is underlined by its enactment of the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act3 which is aimed at advancing social and economic justice.4 This Act represents an attempt by government to achieve substantive equality5 by placing black people in a position to fully participate in all spheres of society in order to develop their full human potential. The Act strives towards transforming society through the dismantling of economic inequality and is widely regarded as the preeminent vehicle for the redistribution of wealth in post-apartheid South Africa. It further represents an attempt to address the disadvantages and vulnerability caused by apartheid and consequently has a clear remedial nature.6

The need to address the economic imbalances brought about by apartheid was aptly described in Viking Pony Africa Pumps (Pty) Ltd t/a Tricom Africa v Hidro-Tech Systems (Pty) Ltd and another7 where Justice Mogoeng stated:

One of the most vicious and degrading effects of racial discrimination in South Africa was the economic exclusion and exploitation of black people. Whether the origins of racism are to be found in the eighteenth and nineteenth century frontiers or in the subsequent development of industrial capitalism, the fact remains that our history excluded black people from access to productive economic assets.

This statement re-affirms the position as set out in the Preamble to the BEE Act which states that under apartheid race was used to control access to, and ownership of, South Africa's productive resources. Based on this statement, it is evident that Black economic empowerment (BEE) forms an essential part of redressing the legacy of apartheid, bringing about social redress and addressing economic inequality.

Through the BEE framework, provision is made to address the economic needs of a section of society that has been severely disadvantaged by past government policies. As the economic needs are progressively addressed, greater access for instance, to education and housing, would become available.8 Without the envisaged economic resources which would follow Black economic empowerment, "self-realisation for the individual and the group remains a hollow concept".9 Such a failure in turn would pressure the government to see to the progressive realisation of the socio-economic rights included in the Bill of Rights.

The introduction of the notion of broad-based black economic empowerment signalled a distinct policy shift away from the much narrower approach followed before the enactment of the Act, which focussed predominantly on the deracialisation of business ownership and control as opposed to issues such as enterprise development or socio-economic development.10 The outpouring of critique11 against the narrow approach, with its limited focus on ownership and control, compelled the government to repackage Black economic empowerment in such a manner as to be seen not only as a project of equity redistribution but also as an intervention aimed at improving the socio-economic position of Black South Africans.12

Against this background this article submits that, within the South African context, BEE is a useful tool for upliftment and that it has ties to the corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement. Furthermore that in some instances BEE can, to some extent, be regarded as an adapted version of CSR. This article will identify elements in the BEE Generic Scorecard which could be linked to the general notion of CSR to illustrate that, although the government has not taken any explicit steps to support CSR, implicit support exists through the BEE framework. This article commences with a brief explanation of key concepts, such as, BEE and CSR, whereafter the BEE Generic Scorecard is discussed. Based on the discussion of the Scorecard, four elements are identified as having CSR content. These elements will be discussed individually and the article will conclude with some recommendations regarding the proposed way forward.

2 KEY DEFINITION

2.1 Defining "Black economic empowerment"

According to section 2 of the BEE Act, broad-based Black economic empowerment will be achieved through the promotion of economic transformation in order to enable the meaningful participation of Black people in the economy; a substantial change in the racial composition of ownership and management structures; the promotion of investment programmes leading to meaningful participation in order to achieve sustainable development; and the empowerment of communities by enabling access in areas, such as, skills development and access to land.13 One of the ways in which the economic transformation is envisaged is through programmes of skills training and skills development. With its nuanced focus on transformation, it is important to establish how "Black economic empowerment" is defined. Section 1 of the Act defines "broad-based black economic empowerment"14 as:

[T]he economic empowerment of all black people, including women, workers, youth, people with disabilities and people living in rural areas through diverse but integrated socio-economic strategies that include but are not limited to -

(a) increasing the number of black people that manage, own and control enterprises and productive assets;

(b) facilitating ownership, and management of enterprises and productive assets by communities, workers, cooperatives and other collective enterprises;

(c) human resource and skills development;

(d) achieving equitable representation in all occupational categories and levels in the workforce;

(e) preferential procurement;15 and

(f) investment in enterprises that are owned or managed by black people.16

From the above definition it is clear that BEE is not only concerned with increasing the levels of Black ownership but also includes the general upliftment of previously disadvantaged individuals and communities, inter alia, through human resource and skills development and socio-economic development. Based on the elements of this definition, a Generic Scorecard has been created to measure the level of compliance in terms of the BEE Act and the Codes of Good Practice on Black Economic Empowerment.

2.2 Defining "Black people"

The definition of "Black people" is central to understanding BEE, which is specifically aimed at empowering black persons through BEE transactions and BEE initiatives.17

Section 1 of the BEE Act defines "black people" as "Africans, Coloureds and Indians".18 The Codes of Good Practice on Black Economic Empowerment19 further define "black people" as

[N]atural persons who are citizens of the Republic of South Africa by birth or descent; or are citizens of the Republic of South Africa by naturalisation; (a) occurring before the commencement date of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act of 1993; or (b) occurring after the commencement date of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act of 1993, but who, without the Apartheid policy would have qualified for naturalisation before then.

It is important to note that the beneficiaries of the envisaged empowerment are "black persons" as per the definition provided by the BEE Act and the General Code, as opposed to other legislation, such as, the Skills Development Act and the Employment Equity Act, which refer to "historically disadvantaged South Africans" - a wider concept which includes white women as a group as well as persons with disabilities.20

2.3 Defining "corporate social responsibility"

Any attempt to define "CSR" should in the first instance recognise that the definition can differ from society to society and can be influenced by factors, such as, culture and belief. This variability contributes to the inability to formulate a single universally accepted definition.21 The South African position serves as an excellent example. Local businesses are not totally comfortable with the use of the term "CSR" possibly as a result of a negative perception of the notion of 'responsibility' and prefer the term "corporate social investment" (CSI). However, a good case can be made for the view that CSR and CSI do not have the same meaning and that one is a consequence of the other -due to an acceptance of social responsibility, social investments are made. Furthermore, it appears as if the legislator is not comfortable with the use of the term CSR either, and has preferred to use terms, such as, "CSI" or "socio-economic development" (SED).

However, regardless of a particular history or culture, it is impossible, even within the context of a particular country, to define "CSR" to such an extent that it would be applicable in each instance. As a result "CSR" should rather be used as an umbrella term to indicate that businesses have a responsibility towards the societies within which they operate and that this responsibility needs to be managed. For the purposes of this article "CSR" will thus be defined in broad terms, and the definition provided by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) in its Guidance on social responsibility22 will be used as a useful point of departure. In terms of this guidance, social responsibility is defined as the

[R]esponsibility of an organization for the impacts of its decisions and activities on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behaviour that contribute to sustainable development, health and the welfare of society; takes into account the expectations of stakeholders; is in compliance with applicable law and consistent with international norms of behaviour; and is integrated throughout the organization and practised in its relationships.

Before the link between CSR and BEE and the Generic Scorecard can be discussed, it is necessary to briefly reflect on the drivers of CSR.

3 DRIVERS OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

CSR drivers refer to those incentives or pressures directed at businesses to improve their socially responsible practices. A variety of drivers exists and the drivers discussed in this paragraph are not necessarily applicable to every business. Mazurkiewicz23 distinguishes between three types of drivers: economic drivers, social drivers, and political drivers. Economic drivers include company image/reputation; competitive advantage and competitiveness; pressure from consumers and pressure from investors. Social drivers are pressure from NGOs; the need to be licensed to operate; and pressure from local communities. Political drivers refer to legal and regulatory drivers and political pressure. Drivers of CSR could include shareholder or investor activism; reporting requirements requiring businesses to voluntarily or involuntarily report on a variety of issues such as social, economic and environmental issues; peer or civil society pressures; consumerism; and government pressures.24 For purposes of this article government pressure is identified as the driving force.

Many businesses engage in CSR initiatives in order to avoid governmental regulations. As soon as regulations are put in place a business's ability to manoeuvre is restricted and the business is forced to comply with the regulations together with the added costs of compliance. Governments are in a situation where they can promote CSR as an indirect form of regulation.25 The Commission of the European Union26 has identified the important contribution that CSR initiatives can make in reaching public policy objectives. These objectives include investment in skills development, the better utilisation of natural resources, and poverty reduction.27

In the national context, government to some extent has played a role in thrusting CSR onto the corporate agenda and creating an enabling environment.28 This was done mainly through legislative measures such as the BEE Act, the Generic Scorecard and the BEE Sector Charters, such as, the Mining Charter and the Financial Sector Charter, which include CSR (or CSI or SED) as an element of the BEE scorecards.29

4 THE GENERIC SCORECARD

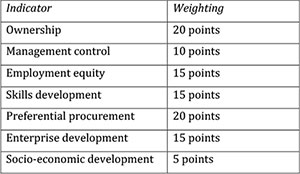

In order to assess the extent to which businesses comply with the BEE measures, section 9(1) of the BEE Act authorises the Minister of Trade and Industry to issue Codes of Good Practice to promote the purpose of the Act, which Codes may include indicators used to measure the rate of compliance together with the weighting to be attached to the indicators.30 The indicators and the weight attached to each indicator were finalised in the General Codes.31 The indicators used to measure compliance are set out in a Generic Scorecard and include, amongst other factors, ownership,32 management control,33 employment equity, skills development, preferential procurement, enterprise development and socio-economic development initiatives. Each of these indicators is afforded an individual weighting as set out below:

Based on the overall levels of compliance with these indicators, a measured entity34 receives a particular BEE status and a subsequent BEE recognition level. The recognition level is used to indicate, as a percentage, the level of recognition which a business will receive in its dealings with the State or other businesses. The recognition level is determined by the number of points that a business scores on the Generic Scorecard.35 A level one contributor is a business which received more than 100 points on the Scorecard and has a BEE recognition level of 135%, while a level eight contributor scored at least 30 but fewer than 40 on the Generic Scorecard and has a corresponding BEE recognition level of 10%.36

The BEE status of a business will in certain instances be used as a determining criterion for the issuing of licences (such as mining licences), concessions or other forms of authorisation.37 The BEE status also plays an important role where State-owned businesses are sold or where the private sector enters into partnerships with the State. A contract between the State and a private business would in all likelihood be awarded to a level four contractor38 rather than, for instance, to a level six contractor.39

The use of a business' level of BEE compliance as a determining criterion is confirmed in section 10 of the Act. This section confirms the legal status of the General Code and other Codes of Good Practice issued in terms of the BEE Act. Section 10 is clear that when determining qualification criteria for the issuing of licences, concessions or other authorisations in terms of any law, or when developing criteria for partnerships between the public and private sectors, every organ of state and public entity must take into account and, in so far as it is reasonably possible, apply the General Code. In other words, in transactions between the State and the private sector, compliance with the BEE Act should be viewed as mandatory, since non-compliance will effectively disqualify the private sector partner from entering into a contract with the State partner. In transactions between two private sector partners, however, compliance remains voluntary, and non-compliance is not a criminal offence. Non-compliance is merely a risk which a business must manage.

Although the generic scorecard makes provision for the allocation of only 5% of the total number of points to socio-economic development (which, due to its nature, is in this context understood to be explicit CSR initiatives), the following sections will examine a number of the other performance indicators which relate to CSR and could also be regarded as being CSR related or having CSR characteristics. The reason for including the indicators which are not labelled as being explicit CSR indicators is to be found in the definition of CSR. The definition of "CSR" provided in the ISO 26000 Guidance on social responsibility is regarded as the most encompassing and internationally accepted one. A business's social responsibility lies, inter alia, in its contribution to sustainable development, including the welfare of society. Having regard to this definition, the following sections will discuss the performance indicators which contribute to sustainable development and the welfare of society.40

5 LINKING CSR TO BEE: CSR AND THE GENERAL CODE

5.1 Introduction

The BEE framework has raised awareness about corporate social obligations and established a platform from which businesses can launch their CSR initiatives and contribute to sustainable development.41 The CSR platform established in the BEE framework consists of four elements which have a distinct developmental aim and which contribute to sustainable development. These elements are skills development, preferential procurement, enterprise development and socio-economic development. The skills development element measures the degree to which employers develop the competencies of Black employees through skills development initiatives. The preferential procurement element assesses the purchase patterns of a business with reference to procurement from other businesses with strong BEE recognition levels. Enterprise development focuses on initiatives undertaken by a business to develop other businesses and assist such businesses to become sustainable. The final element, socio-economic development, measures the extent to which a business contributes to the socio-economic development of Black people. An overview of each of these elements, as contained in the Generic Scorecard of the General Code, follows.42

5.2 Skills development

Skills development and business education lie at the core of the notion of empowerment - the higher the skill level of the national workforce, the greater the benefit would be not only to the economy but also to the beneficiaries of Black economic empowerment. A skilled workforce is a central element of sustainable economic and social development and is essential to achieving global economic competitiveness. Achieving a skilled workforce should consequently be included as a distinct aim in any programme aimed at empowering previously disadvantaged South Africans.43 The first indicator that addresses issues which directly contribute to sustainable development and the welfare of society and which can accordingly be labelled as CSR - related is the indicator dealing with skills development contained in Code 400 of the General Code.44 This Code provides clarity on how the skills development element on the BEE Scorecard will be measured. Besides providing the Scorecard for measuring the skills development element of the Generic Scorecard, the Code also defines the key measurement principles associated with this element.

Before making any skills development contributions, a business needs to be familiar with the definition of "skills development." Once it has an understanding of how "skills development" is defined, a business must establish which contributions will be recognised as qualifying as skills development expenditure. Finally, a business needs to identify the contribution target in order to receive the maximum number of points allocated to the skills development element.

As was previously stated, the weighting allocated to the skills development element of the Generic Scorecard is 15 points (or 15%). The skills development Scorecard makes provision for two sub-categories addressing skills development expenditure. Nine points are allocated to skills development through learning programme investment on any programme specified in the Learning Programmes Matrix,45 and six points are allocated to contributions through learnerships. The first category is subdivided into two further categories. The first measures skills development expenditure on programmes specified in the Learning Programme Matrix for Black employees as a percentage of the leviable amount46 using the Adjusted Recognition for Gender,47 while the second measures the number of Black employees participating in learnerships of Categories B, C and D Programmes as a percentage of the total employees.48

Businesses may be scored in terms of the skills development Scorecard only if they have complied with the requirements of the Skills Development Act and the Skills Development Levies Act and have been registered with an applicable SETA, have a Workplace Skills Plan in place, and have implemented programmes targeting the development of priority skills,49 especially for Black employees.50

One of the criteria laid down to assess a business's level of compliance with the requirements set for skills development is the amount spent on priority skills for Black employees. The focus on priority skills is a confirmation of government's commitment to ensure that skills development is not limited to peripheral skills but is extended to skills which would enable employees to become active in the mainstream economy.51 A business will be measured by the amount it spends on skills development over and above the amount levied in terms of the Skills Development Levies Act.52 Should any of the employees on which money is spent be Black women, the business will receive an Adjusted Recognition for Gender. This supports the government's commitment to the upliftment of women in particular.

In quantifying the amount spent on skills development not only are the direct training costs, such as, costs of trainers and training materials, taken into consideration, but also indirect costs, such as, accommodation and travel costs. In order to improve the rate of literacy amongst employees, the Code states that any skills development expenditure on an Adult Based Education and Training (ABET) programme is recognisable as a multiple of 1.25 of the value spent.53

The criteria laid down for measuring the level of compliance with the element of skills development, however, do have serious shortcomings. The most important shortfall in this Code is the fact that reference is made only to employees. Should a business as part of its CSR agenda assist in the development of the skills of members of one of its stakeholders (other than employees), like a local community,54 it would invariably not receive any recognition in respect of the skills development element of the overall Scorecard, despite the time, money and effort spent. The business, however, would be "rewarded" for its efforts in respect of the socio-economic development element of the Scorecard. This part of the Scorecard regrettably provides for only 5 of the allocated 100 points that a business can score, while the skills development of employees provides for 15 of the possible 100 points.55

This is not to argue that the skills development of employees is in any way less important than the development of the skills of a local community. Regardless of the fact that businesses do not score as many points on the BEE Scorecard for their "traditional" CSR efforts as they do for employee skills development, they should continue to assist in the upliftment of those who are not their employees.

The aim of the skills development element is to improve the level of skill of the national workforce, and as such it is focussed internally on the business. However, businesses do not operate in a vacuum but are part of a larger economy. In this regard businesses are procuring goods and services from preferred suppliers in a supply chain in order to continue doing business. The following section will provide an overview of the preferential procurement element in the Generic Scorecard - the element which assesses the level of procurement from preferred suppliers.

5.3 Preferential procurement

The preferential procurement indicator measures the extent to which a measuring entity has purchased goods or services from suppliers with a high BEE procurement recognition level.56 The idea behind preferential procurement is to encourage businesses to procure only from suppliers who are in compliance with the BEE guidelines. In this regard, the voluntary nature of BEE compliance in the private sector might undergo a change and become mandatory. Although BEE in the private sector is voluntary, the purchasing patterns of a business can influence another business to comply with BEE, thus resulting in it becoming mandatory. BEE becomes mandatory to the extent that if a business chooses not to comply, it would not be an attractive supplier to other businesses and would accordingly lose business, to its detriment.

From a CSR perspective, the value of preferential procurement lies in the contribution which is made to businesses with a recognised BEE status. The ultimate aim of preferential procurement is to enable Black South Africans to become meaningful participants in the national economy. This contributes to sustainable development and the welfare of society at large, which in turn is in line with the international definition of CSR. Preferential procurement is also an important guidance measure to be employed by businesses when determining their stakeholders since suppliers are regarded as important stakeholders in all businesses.57 Through its preferential procurement practices a business demonstrates that it is acting with social responsibility and acknowledges the fact that its business decisions (such as its purchasing patterns) have an impact on society.58 Preferential procurement can potentially become an important mechanism which businesses can use to meet their CSR obligations.

A measured business will be scored on the basis of the procurement recognition level of its suppliers. Code 500 of the General Code provides the preferential procurement Scorecard, which accounts for 20% of the overall points against which a business is measured in terms of the Generic Scorecard. The importance of this element is emphasised by the fact that it, together with the ownership element, carries the highest weighting in terms of the Scorecard.

One of the main reasons for the inclusion of preferential procurement in the Generic Scorecard is to encourage businesses to make their procurements from Black -owned suppliers (or suppliers with a high BEE status) in order to assist these suppliers to meaningfully participate in the economy. The value of this element lies in what is referred to as "the trickledown effect." Since organs of State and public entities are, by law, required to comply with the provisions of the BEE Act, the trickledown effect will best be described in this context. Organs of State and public entities are required to procure from suppliers with an acceptable BEE status. Should the business from which procurement may be done (also referred to as a first-tier supplier) not have an acceptable BEE status, the organ of State or public entity will not procure from that business and it, together with all the businesses in its supply chain, will be eliminated from the list of suppliers to the State entity. The level of BEE compliance of first-tier suppliers is dependent inter alia on its procurement from downstream or second-tier suppliers. As a result of this, every business will pressurise its downstream suppliers to comply with the requirements of the Generic Scorecard in order to ensure that the first-tier supplier has a high score with regard to the preferential procurement element.59

The preferential procurement Scorecard allocates 12 weighting points to BEE procurement spent on all suppliers, based on the BEE procurement recognition levels as a percentage of total procurement expenditure. In order to receive all of the points available, a business is required to initially spend at least 50% of its total procurement expenditure on goods or services purchased from suppliers with a high BEE rating. A further 3 points are allocated to BEE procurement spent on qualifying small enterprises or exempted micro-enterprises, based on the applicable BEE procurement recognition levels as a percentage of total measured procurement spent.60 The final criteria on the Scorecard measure the BEE procurement spent on suppliers who are 50% black owned61 (3 points) and suppliers that are 30% Black women owned62 (2 points), as a percentage of total measured procurement expenditure.

The following expenditure is to be included in the total measured procurement spent: cost of sales, operational expenditure, capital expenditure, pension and medical aid contributions, and empowerment related expenditure (which excludes contributions recognised as being part of enterprise development or socio-economic development contributions). Expenditures, such as, taxes, salaries, wages and remuneration or any amount payable to an employee in terms of a service agreement, are also excluded from the total measured procurement spent.63

Whereas preferential procurement measures the extent to which enterprises buy goods or services from suppliers with strong BEE recognition levels, the enterprise development element evaluates the initiatives that the business takes which are aimed at assisting and accelerating the development and sustainability of other businesses. The following section will discuss the enterprise development element of BEE.

5.4 Enterprise development

The broad aim of enterprise development is to encourage social investment as well as to stimulate Black businesses, and as a result this element is one of the key CSR related initiatives in the BEE framework. It directly encourages Black entrepreneurs to participate in the economy in order to stimulate economic growth. Both the preferential procurement element and the enterprise development element have an outward focus, whereas the primary focus is on businesses in the supply/value chain or those with the ability to enter the value chain. Jack64 states in this regard:

Encouraging the support of enterprise development through preferential procurement stimulates reciprocal needs between the investor and the beneficiary and will ultimately lead to sustainable development of Black business. The enterprise development element encourages investment in Black business, while preferential procurement supports sustainability through ongoing procurement from the developed enterprise.

This statement aptly describes the relatedness between the two elements and provides support for the argument that businesses have an important role to play in the development and transformation of the private sector. Enterprise development as an element is aimed at getting Black entrepreneurs to become economically active and to participate in the economy. In this regard enterprise development can be considered as a manifestation of CSI, where a business makes a strategic investment in a potential future supplier. For example, if an agricultural company, such as, Senwes or Suidwes, which specialises in the grain industry in the North-West Province, wants to make a strategic investment which would contribute to enterprise development, becoming involved in the land reform programme with potential emerging Black farmers would be an ideal starting point. Through its knowledge and expertise the business could assist land reform beneficiaries who wished to become involve in commercial farming, thus contributing to enterprise development and broadening its potential future supply of produce. Agri-businesses such as the major agricultural companies are strategically well positioned to provide massive inputs into enterprise development, which in turn could prove to be the answer that everyone is looking for in directing the land reform programme towards a successful outcome.

The enterprise development element of the Generic Scorecard accounts for 15% of the total points available. The criterion used to determine the level of compliance in terms of this element is the average annual value of all enterprise development contributions65 and sector specific programmes made by the business as a percentage of the target of 3% of net profits after tax.66 According to Code 600 of the General Code, enterprise development contributions consist of

[M]onetary or non-monetary, recoverable or non-recoverable contributions actually initiated and implemented in favour of beneficiary entities by a Measured Entity with the specific objective of assisting or accelerating the development, sustainability and ultimate financial and operational independence of that beneficiary. This is commonly accomplished through the expansion of those beneficiaries' financial and/or operational capacity.67

From the above definition it is clear that enterprise development has a very strong, nuanced focus on sustainable development, which is in line with the working definition of CSR adopted throughout this article. In this regard enterprise development can be seen as a manifestation of the practical implementation of social responsibility. Enterprise development to be regarded not only as a crucial instrument of development, but also as a prime contributor to achieve the overall aim of BEE through the empowerment of previously disadvantaged South Africans.

Although the definition of enterprise development refers to contributions actually initiated and implemented in favour of beneficiary entities, paragraph 3.2.9 of Code 600 recognises the cost of providing training or mentoring to beneficiary communities as a qualifying enterprise development cost. This paragraph contains the only reference to beneficiary communities in the Code and the question should be raised whether the reference to communities in this regard was intentional or not. Strictly speaking, the provision of training or mentoring to communities falls within the ambit of socio-economic development, which is addressed in Code 700 of the General Code, an element with the lowest weighting of all of the elements of the Generic Scorecard. But if the legislator intended to include contributions to communities under enterprise development, businesses are in the position where they can provide training or mentoring to communities and achieve a higher score under this element than would be possible under the socio-economic development element.

Examples of enterprise development contributions include grant contributions68 to beneficiary entities; investments in, or loans69 made to, or credit facilities made available to, beneficiary entities; the provision of training or mentoring to beneficiary entities enabling the beneficiary entities to increase their operational or financial capacity; or providing training or mentoring to beneficiary communities.70

Before a business decides on enterprise development contributions it is of the utmost importance that it identifies its targeted beneficiaries through a process of stakeholder mapping and stakeholder engagement. Once the beneficiaries are identified, their needs should be identified through a process of inclusive stakeholder dialogue. The needs of the beneficiaries should be identified through a consultative process instead of the business prescribing to them what it perceives their needs to be. When the beneficiaries and their needs have been identified, the parties should come to an agreement regarding the terms and objectives of the proposed development initiatives. This agreement could take the form of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the parties in terms of which the responsibilities of each party are spelled out together with a predetermined exit strategy allowing partners to exit from the agreement in certain instances, as well as the indicators and criteria to be used in order to measure the success of the collaboration.

The effect of enterprise development is that it would lead to an improvement in the socio-economic position of the targeted beneficiaries. However, included in the Generic Scorecard is the socio-economic development element, which could be viewed as a "catch-all" element as a result of its broadly stated aim. The following section will discuss this final element and refer to the possible overlap between the elements of enterprise development and socio-economic development.

5.5 Socio-economic development

It is accepted that CSR has become a fundamental part of the corporate mandate and that the role of the private sector in transformation and development is ever increasing. As a result of the intensified focus on CSR, the Generic Scorecard has included socioeconomic development as ("SED") one of the criteria against which a business' overall BEE compliance is measured. From a CSR perspective this measuring element represents the most important step towards entrenching CSR in a legal framework. The inclusion of the SED element is a re-affirmation of government's attempt to promote sustainable access to the economy, and as such the initiative is a welcome step toward empowering previously disadvantaged Black persons.

Code 700 identifies SED contributions as those contributions which have actually been initiated and implemented in favour of beneficiaries "with the specific objective of facilitating access to the economy for those beneficiaries".71 This formulation is much wider than the one provided in Schedule 1 (which provides a list of definitions) and it is argued that in measuring a business's level of compliance with the compliance target, this wider formulation should be followed. This wider formulation is in line with the objectives of the BEE Act to promote economic transformation which would result in the meaningful participation of Black people in the economy and to empower local communities through access to economic activities, land and skills.72 If at least 75% of the SED contributions are to the direct benefit of Black people, the full value of the contributions will be recognisable. If less that 75% if the contributions are to the direct Benefit of black people, the value of the contribution made, multiplied by the percentage of direct Black benefit, is recognisable.73

The SED contributions of a business are measured in terms of the SED Scorecard included in Code 700 of the General Code, which uses the average annual value of all SED contributions of the business as a percentage of the compliance target of 1% of net profits after tax. Five weighting points are allocated to the SED Scorecard, making this element the element with the lowest weighting of all the elements. Schedule 1 of the General Code defines "approved social-economic development contributions" as:

[M]onetary or non-monetary contributions carried out for the benefit of any projects approved for this purpose by any organ of state or sector including without limitation: (a) projects focussing on environmental conservation, awareness, education and waste management; and (b) projects targeting infrastructural development, enterprise creation or reconstruction in underdeveloped areas; rural communities or geographic areas identified in the government's integrated sustainable rural development or urban renewal programmes.

In the preceding discussion of the enterprise development element of the Generic Scorecard, it was noted that the provision of training and mentoring to beneficiary communities was a recognisable enterprise development contribution. From the definition of SED contributions in Schedule 1 of the General Code it is evident that these two elements overlap further. In terms of Schedule 1, contributions toward projects which target enterprise creation or reconstruction in certain identified areas74 will qualify as SED contributions, while they appear to be contributions which are aimed at enterprise development and which should be measured in terms of the enterprise development element.

To add further confusion to the distinction between the elements it is noted that the non-exhaustive list of SED contributions, for example, refers to grants made to the beneficiaries of SED contributions (which, as noted in the preceding paragraph, include contributions which could clearly be classified as being enterprise development contributions), as well as developmental capital advanced to the beneficiaries, both of which are also identified as being enterprise development contributions.75 The confusion is further increased by the fact that paragraph 3.2.9 of Code 600 and paragraph 3.2.6 of Code 700 are almost exact replicas of each other except for some minor semantic differences.76 It is recommended that this situation be addressed in future amendments of the Code.

SED contributions could also refer to those contributions made to programmes which are aimed at the development of women, youth, people with disabilities and people living in rural areas, as well as those programmes which provide support for healthcare and HIV/Aids. It could further include support for education programmes and programmes focussing on community training (including skills development for unemployed persons and adult basic education and training) or support arts, cultural or sporting development.77

6 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Despite the fact that BEE has produced limited structural change in the lives of the majority of South Africans, BEE initiatives still represent one of the most crucial vehicles whereby the private sector can give expression to its CSR objectives. BEE remains decisive for transforming South Africa into a more just and equitable society.78 Although the Generic Scorecard allocates only 5 out of a possible 100 points to socio-economic development contributions, thus possibly indicating that this element is of lesser importance in terms of the Scorecard, this article has, in accordance with the ISO 26000 definition of CSR, been able to show that various other elements included in the Generic Scorecard can be categorised as being manifestations of a business's social responsibility. If implemented in the spirit of BEE, the elements of skills development, preferential procurement and enterprise development all contribute to sustainable development, including the welfare of society, which is contained in the definition of a business's social responsibility.

However, it is evident that due to its voluntary nature these "softer" issues have been neglected and that the BEE Act has to date failed to achieve its objectives of empowerment. A possible solution to the problem could lie in a change in the application and enforceability of the BEE Act and the General Code. With regard to the private sector, it is recommended that the elements of ownership and management and control retain their voluntary nature, implying that businesses have the choice whether they want to comply with the guidelines or not. This would allay investor fears that established businesses might suddenly change their ownership and management structures merely to comply with requirements which could threaten their sustainability.

On the other hand, it is recommended that the CSR elements (skills development, preferential procurement, enterprise development and socio-economic development) be grouped together in a separate CSR Scorecard and that compliance be made mandatory. The problem which may arise in case of a mandatory framework is how to monitor compliance and censure non-compliance. Given the current situation in some State departments, it is suggested that the South African Revenue Service (as the administrator of the tax system) is the most qualified branch of government to be tasked with ensuring compliance. It is proposed that businesses be encouraged to comply through the use of tax incentives. Businesses with a high level of compliance, for instance, could be taxed at a lower rate than businesses with the same taxable income but with a lower level of compliance. Alternatively, the rate at which CSR expenditure is allowed as expenditure actually incurred in the production of income can be increased or decreased depending on the rate of compliance. It is proposed that the level of compliance or non-compliance be "rewarded" in terms of the sliding scale principle where, for instance, a business with a 100% compliance rate will be able to multiply its CSR expenditure with a factor of 1.5 or businesses with a compliance rate of only 50% will be able to deduct only a fraction of the total qualifying expenditure (for example the actual expenditure multiplied by a factor of 0.5). Unfortunately the obvious shortcoming of this approach is that businesses that decide not to comply at all will still not be penalised. An alternative could be that the rate at which a business is taxed is increased or decreased depending on its level of compliance. If, for example, two businesses have the same taxable income and one is compliant and the other non-compliant, the non-compliant business will be taxed at a higher rate than the compliant one. This will encourage non-compliant businesses to comply in order to be taxed at a lower rate.

With a mandatory focus on these elements the objectives of the BEE Act stand a greater chance of being achieved, since the focus is much wider and the range of beneficiaries is much wider, contrary to the current state of BEE transactions, which simply focus on equity. The focus of the CSR elements is on the genuine empowerment of marginalised South Africans. CSR has the ability to attract black entrepreneurs, to develop the levels of skill and education in communities, to assist in creating more awareness regarding health issues, and to create value down a business's supply chain. However, in order for these elements to achieve these ambitious goals it is essential that effective institutional structures exist which would provide assistance to businesses in their efforts to contribute to empowerment.

With reference to preferential procurement, it is important for businesses to know what the BEE (CSR) status of potential suppliers is, in order to guide their decision of whether or not to procure from a supplier. This can be achieved only if the BEE (CSR) status of potential suppliers has been established and externally verified by an accredited rating agency. Unfortunately, many current ratings have not been provided by accredited rating agencies, a fact which poses a serious threat to the legitimacy of the process.79 If a business procures from a supplier whose BEE (CSR) status has not been verified, it is in danger of losing points on the scorecard, which in turn would affect its BEE (CSR) rating. It is proposed that the Department of Trade and Industry create a national rating register containing businesses' ratings. Businesses could then consult this national database in order to confirm a prospective supplier's current rating. In order to alleviate the administrative burden which this might place on businesses, it is recommended that businesses be required to be rated at least once every two years. In the periods between ratings, businesses will retain their rating until the next rating.80

The elements of enterprise development and socio-economic development have a nuanced developmental focus, with a particular focus on the development of communities. It is recommended that the weighting allocated to elements focussing on community development should be increased in order to encourage businesses to become involved with their local communities. This approach would also be in line with the stakeholder theory of CSR, where communities are identified as the stakeholders of a business because they are directly or indirectly affected by its actions and decisions. Since both the elements of enterprise development and socio-economic development address community development, it is proposed that community development be removed from enterprise development and that an additional element which focuses exclusively on community development be included in the CSR Scorecard.

1 See par 2 for an explanation of the term "Black". It should be noted that the content of this discussion reflects the legal position as at 1 October 2013.

2 The BEE framework is directly aimed at addressing issues related to economic redistribution and wealth creation (Van Rensburg J The Constitutional framework for broad-based Black economic empowerment (Unpublished LLD thesis University of the Free State (2010)) at 121. [ Links ]

3 Act 53 of 2003 ("the BEE Act").

4 This Act was introduced in terms of the mandate provided in the Constitution to promulgate legislation which promotes conditions of equality and eradicates the legacy of the past.

5 Albertyn C "Substantive equality and transformation in South Africa" (2007) 23 SAJHR 253-276 at 253 suggests that "the idea of substantive equality contemplates both social and economic change and is capable of addressing diverse forms of inequality that arise from a multiplicity of social and economic causes, [ Links ]" and notes that substantive equality can be achieved only through the dismantling of systemic inequalities, the eradication of poverty and disadvantage (economic equality) and the affirmation of human identity and capabilities (social equality) (at 257). For detailed discussion of substantive equality within the South African dispensation, see volume 25 of the 2009 edition of SAJHR.

6 Albertyn C "Equality" in Cheadle H, Davis D & Haysom B South African constitutional law: The Bill of Rights (2010) at 4:6. [ Links ] Ponte S, Roberts S & Van Sittert L "Black Economic Empowerment, business and the state in South Africa" (2007) 38 Development and Change 933 - 957 at 936 argue that BEE fits well within the developmental state with its primary objective of empowering Black South Africans. [ Links ]

7 2011 (1) SA 327 (CC) at 329.

8 However, the inverse is also true. The less economically empowered an individual is, the more likely it is that the individual would have access to housing or healthcare services (as envisaged by ss 26 and 27 of the Constitution).

9 Van Rensburg (2010) at 123-124.

10 For a more detailed discussion of the distinction between BEE in narrow and broad terms, see Glaser D "Should an egalitarian support Black economic empowerment?" (2007) 34 Politikon 105 - 123 at 106-114; [ Links ] and Southall R "Black economic empowerment and corporate capital" in Danial J, Southall R & Lutchman J (eds) State of the Nation: South Africa 2004-2005 (2005) at 456-457. [ Links ]

11 For a discussion of the critique not only of narrow BEE but also of its broader application, see Kloppers H Improving land reform through CSR: A legal framework analysis (Unpublished LLD thesis North-West University (2012)) at 254-266. [ Links ]

12 For a more detailed discussion of the evolution of BEE from its narrower application in the earliest instruments, such as, the Freedom Charter to its broader application, see Jack V The complete guide (2007) at 1-61; Gqubule D "The true meaning of BEE" in Gqubule D Making mistakes, righting wrongs -insights into Black Economic Empowerment (2006) at 1-39; [ Links ] Ponte S, Roberts S & Van Sittert L To BEE or Not to BEE? (2006) at 9-32; [ Links ] Ponte, Roberts & Van Sittert (2007) at 933-957; and Southall R The logic of Black economic empowerment (2006) at 1-22. [ Links ]

13 This approach is contrary to the narrow approach to BEE which primarily focuses on changes in equity and management.

14 For the purposes of this article reference to BEE will refer to broad-based BEE as opposed to the previous notion of narrow BEE. The "Draft BEE Amendment Act" proposes changes to the existing definition of broad-based black economic empowerment as included in s 1 of the BEE Act. In terms of the proposed change, BEE refers to the "sustainable economic empowerment of all black people, [including] in particular women..." It is likely that the proposed amendment is aimed at reinforcing the notion that BEE should be sustainable and be able to make a continuous contribution to empowering Black people.

15 S1(c)(e) of the Draft BEE Amendment Act proposes that the scope of preferential procurement should be broadened to include the promotion of local content procurement.

16 In terms of the Generic BEE Scorecard which is discussed in the following sections, this aspect can also be labelled as "Enterprise development".

17 The Draft BEE Amendment Act defines a BEE transaction as "any transaction, practice, scheme or other initiative which affects, or may affect, the B-BBEE compliance of any person". Although some literature refers to B-BBEE, an acronym which refers to broad-based black economic empowerment, this research will simply refer to black economic empowerment (BEE).

18 The Draft BEE Amendment Act proposes a substitution for the existing definition of black people (as opposed to "black persons"). According to the Draft Act "black people" is a generic term which refers to Africans, Coloureds, and Indians "who are citizens of the Republic of South Africa by birth or descent or who became citizens of the Republic of South Africa by naturalisation - (a) before 27 April 1994; or (b) on or after 27 April 1994 and who have been entitled to acquire citizenship by naturalisation prior to that date but were precluded from doing so by Apartheid policies" (italics added to emphasise the proposed substitution). In an unreported Transvaal High Court case of Chinese Association of South Africa & others v The Minister of Labour & others (case no 59251/2007), the definition of "black people" was extended to include South African Chinese people, who now fall within the definition of black people as referred to in the General Code. The proposed amendment will bring the definition in line with the Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998. However, it is interesting to note that the definition of "black people" in the 2013 Codes of Good Practice (Notice 1019, GG 36928 of 11 October 2013) does not make any reference to the inclusion of South African Chinese people.

19 GN 112, GG 29617 of 9 February 2007 ("the General Code").

20 Although the definition of "black people" in the Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998 is the same as the definition included in the BEE Act, the Employment Equity Act attempts to redress the disadvantages in employment experienced by designated groups, a term which includes white women and (white) people with disabilities. The Skills Development Act 97 of 1998 (an Act aimed at developing the skills of the South African workforce) does not provide a definition of black people, but instead also refers to "designated groups", which term carries the same meaning as the definition in the Employment Equity Act. For a discussion of the beneficiaries of BEE, see Jack (2007) at 46-61 and Kloppers E & Kloppers H "Skills development as part of CSR: A South African perspective" in Hooker J, Hupke J & Madsen P (eds) Controversies in international corporate responsibility (2007) at 422.

21 Blowfield M & Frynas JG "Setting new agendas: critical perspectives on Corporate Social Responsibility in the developing world" (2005) 81 International Affairs 499-513 at 502: "This vagueness restricts CSR's usefulness both as an analytical tool and as a guide for decision-makers."

22 ISO 26000 Guidance on social responsibility (2010) at 3.

23 Mazurkiewicz P "Corporate environmental responsibility: Is a common CSR framework possible?" 2004 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTDEVCOMMENG/Resources/csrframework.pdf.

24 For a full discussion on the drivers of CSR, see Kloppers (2012) at 186-194.

25 Vogel D The Market for Virtue: The potential and limits of corporate social responsibility (2005) at 11.

26 European Commission Implementing the partnership for growth and jobs: Making Europe a pole of excellence on corporate social responsibility COM(2006) 136 (2006) at 4.

27 Other public policy objectives that CSR initiatives can assist in reaching include more integrated labour markets, higher levels of social inclusion, and improvements in public health resulting from businesses becoming involved in providing consumers with nutritional advice on food products, for instance (EC COM(2006) 136 (2006) at 4).

28 For a discussion of the role of government in creating a CSR-enabling environment, see Kloppers H "Creating a CSR-enabling environment: The role of Government" (2013) 28 Southern African Public Law at 121-145.

29 De Wet remarked: "The charter process laid the groundwork for new laws and regulations which have served to entrench CSI as a formal part of the corporate sector's contribution to broad-based transformation." See De Wet H (ed) The CSI Handbook 12th ed (2009) at 5.

30 Ss 9(1)(c) and (d) of the BEE Act.

31 On 9 February 2007 the final Codes of Good Practice on Black Economic Empowerment were gazetted (GN 112, GG 29617 of 9 February 2007. At the end of 2005 the Minister of Trade and Industry issued the Draft Code of Good Practice but for the purposes of this research the focus will be on the final version of the General Code, except to the extent that it is necessary to refer to the Draft Code. As will become evident from the discussion of the content of the General Code, a number of notable differences occur between the content of the two documents, especially with reference to the CSR contents thereof.

32 According to the Department of Trade and Industry Code of Good Practice on BEE of 2004 "the DTI General Code" at 23), ownership in terms of the Scorecard is divided into voting rights (which refer to exercisable voting rights, which are voting rights attached to an equity instrument owned by or held for a participant (DTI General Code at 93)) and economic interest (which refers to a claim against a business representing a return on ownership of the business and which is similar in nature to a dividend right (DTI General Code at 89).

33 This indicator allocates points based on the number of exercisable voting rights of Black board members, the number of Black executive directors, the number of Black senior top management and the number of Black other top management (DTI General Code at 46).

34 The General Code refers to measured entities as opposed to businesses or enterprises. Since the focus of this research is on the measured entities from the private sector, the rest of the sections will refer to businesses as opposed to measured entities. Any reference to "business" will imply a measured entity, unless otherwise stated.

35 Kloppers H & Du Plessis W "Corporate Social Responsibility, legislative reforms and mining in South Africa" (2008) 26 Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 91-119 at 99.

36 DTI General Code at 11. It is noteworthy that in terms of the Generic Scorecard, a business can score a maximum of 102 points, with the ownership element being the only one on the current scorecard that makes provision for bonus points.

37 S 10(a) of the BEE Act.

38 A business with a 100% BEE recognition level, and scoring at least 66 but fewer than 75 points on the Generic Scorecard.

39 A business with an 80% BEE recognition level, and scoring at least 45 but fewer than 55 points on the Generic Scorecard. Shneiderman D "Promoting equality, black economic empowerment, and the future of investment rules" (2009) 25 SAJHR 246-279 at 255 notes that companies who perform on their scorecards might be "rewarded" for their compliance through the use of government procurement where the potential buying power of the government is used as an incentive for those wishing to do business with the government.

40 ISO 26000 Guidance (2010) at 3. Although the validity of the elements of the Scorecard might be questioned, a discussion of such validity falls outside the scope of this article.

41 According to Hamann R, Khagram S & Rohan S "South Africa's charter approach to post-apartheid economic transformation: Collaborative governance or hardball bargaining?" (2008) 34 Journal of Southern African Studies 21-37 at 27 "it is apparent that BEE ... overlaps considerably with CSR-related issues". The authors further note that "[m]any South Africans see BEE as a prerequisite for, and true manifestation of, CSR, with widespread social benefits." De Wet (2009) at 16 notes that through the BEE framework, CSR "has become an explicit strategic priority for many large companies."

42 It should be noted that very little academic literature has been published on the subject of BEE, and even less addressing any of the specific elements of the Generic Scorecard. As a result, the content of the following paragraphs is largely dependent on the content of the original source, viz, the General Code.

43 For a discussion of the importance of skills development in sustainability, see McGrath S & Akojee S "Vocational education and training for sustainability in South Africa: The role of public and private provision" (2009) 29 International Journal of Educational Development at 149-156.

44 For a discussion of the skills development element, see Jack (2007) at 272-293.

45 The Learning Programme in Matrix is a matrix which provides guidance on the various categories of skills development programmes in which a business can get involved, in order to ensure that its expenditure on skills development will be recognised for the purposes of the skills development Scorecard.

46 "Leviable amount" in this context bears the same meaning that it has in the Skills Development Levies Act 9 of 1999. S 3(4) of the Skills Development Levies Act defines it as follows: "the leviable amount means the total amount of remuneration, paid or payable, or deemed to be paid or payable, by an employer to its employees during any month, as determined in accordance with the provisions of the Fourth Schedule to the Income Tax Act for the purposes of determining the employer's liability for any employees' tax in terms of that Schedule, whether or not such employer is liable to deduct or withhold such employees' tax".

47 The General Code does not provide any definition for "Adjusted Recognition for Gender", but from the formula provided for calculating the "Adjusted Recognition for Gender" it can be assumed that the greater the number of Black women in employment, the greater the corresponding weighting points in terms of the skills development Scorecard would be.

48 Although the category addressing learnerships in the skills development Scorecard does not provide an indication of which Categories B, C and D Programmes it is referring to, it can be assumed that reference is being made to the Learning Programme Matrix.

49 The General Code defines "priority skills" as "Core, Critical and Scare Skills as well as any skills specifically identified: a) in a Sector Skills plan issued by the Department of Labour ... and b) by the Joint Initiative for Priority Skills Acquisition (JIPSA) established as part of the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative - South Africa (ASGISA)" (DTI General Code 91). The code defines "core skills" as those skills that are value-adding activities in line with a business' core business or those within the production or operational component of the businesses' value chain. "Critical skills" are those skills determined by the relevant sector SETA which are regarded as critical for the defined sector. It should be noted that although the terms "core" and "critical skills" are included in the General Code, they are not used as measurement indicators as in the draft Codes, and the question arises why the distinction is made if they are not used as measurement indicators.

50 DTI General Code at 55.

51 Jack (2007) at 277.

52 Act 9 of 1999.

53 DTI General Code at 56. For example, if a business spends R10 000 on training in terms of an ABET programme, the amount recognised as skills development expenditure would be R12 500. For an example of the practical application of the skills development Scorecard, see Scholtz W & Van Wyk C "BEE service" (2010) at 5:6-5:7.

54 Skills development expenditure on persons other than employees would be in line with the CSR principle of community investment as identified in Pitts C Corporate Social Responsibility (2009) at 91.

55 Kloppers & Kloppers (2007) at 422-423.

56 Preferential procurement in this regard should not be confused with preferential procurement in terms of the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act 5 of 2000, which establishes a framework for the implementation of a procurement policy as contemplated in s 217(2) of the Constitution.

57 Identifying stakeholders is one of the seven legal principles identified by the ISO 26000 Guidance (2010) at 12, and one of the legal principles of CSR according to Kerr M, Janda R, & Pitts C (ed) (2009) at 91.

58 For an example of the practical application of the preferential procurement scorecard, see Scholtz W & Van Wyk C BEE Service (2010) at 6:6-6:7.

59 For a schematic illustration of the trickledown effect, see Jack (2007) at 299.

60 In order to receive the full tally of points, the business must spend at least 10% of its annual procurement expenditure on these enterprises (DTI General Code at 60).

61 "50% black-owned" refers to an entity in which "black people hold more than 50% of the exercisable voting rights as determined under Code series 100; (b) black people hold more than 50% of the economic interest as determined under Code series 100 and (c) has earned all the points for Net Value under statement 100" (DTI General Code at 90).

62 "30% black women owned" refers to an entity in which "(d) black women hold more than 30% of the exercisable voting rights as determined under Code series 100; (e) black women hold more than 30% of the economic interest as determined under Code series 100 and (f) has earned all the points for Net Value under statement 100" (DTI General Code at 91).

63 For further reference to expenditure which is included and excluded from the measurement, see Jack (2007) at 310-315.

64 Jack (2007) at 320.

65 Enterprise development contributions are defined as "monetary or non-monetary contributions carried out for the following beneficiaries with the objective of contributing to the development, sustainability and financial and operational independence of those beneficiaries: (a) Category A Enterprise Development Contributions involves Enterprise Development Contributions to Exempted Micro-Enterprises or Qualifying Small Enterprises which are 50% black owned or black women owned; (b) Category B Enterprise Development Contributions involves Enterprise Development Contributions to any other Entity that is 50% black owned or black women owned; or 25% black owned or black women owned with a BEE status of between Level One and Level Six" (DTI General Code at 89).

66 Code 600 of the General Code (DTI General Code at 66).

67 DTI General Code at 67. Emphasis added. The reference to "contributions actually initiated and implemented" has a noticeable link to the general deduction formulae contained in s 11(a) of the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962. S 11(a) provides an indication of which expenses a taxpayer is allowed to deduct from his/her gross income in order to determine his/her normal tax liability. S 11(a) makes provision for the deduction of "expenditure and losses actually incurred in the production of the income" (emphasis added) which seems to be reflected by the reference to "actually initiated and implemented". In line with s 11(a), "actually initiated" implies that as long as the liability to make the contribution has been incurred, the contribution will be recognised as a qualifying contribution. However, reference in Code 600 is further made to "actually initiated and implemented" (emphasis added), which might give rise to the argument that the mere liability to incur the expenditure is not sufficient - "something more", referring to implementation, is required. It appears as if it is required that the contribution has actually been made, which is contrary to the approach in the general deduction formula, where actual payment is not a requirement.

68 In terms of the Benefit Factor Matrix contained in Code 600 of the General Code, a business will be able to claim the value of the full grant amount as an enterprise development contribution. However, when the business incurs overhead costs in support of enterprise development only 80% of the verifiable cost will be included in the calculation of the qualifying contributions (DTI General Code at 70).

69 The full outstanding amount of interest free loans with no security required, supporting enterprise development, will be included in the calculation of the qualifying contributions (DTI General Code at 70).

70 These contributions are contributions which are made in the form of human resource capacity. Contributions made toward providing training or mentoring to beneficiary communities will be measured by quantifying the cost of the time (excluding travel time) spent by employees in carrying out the activities. The cost of time must be justifiable and should be based on the seniority and expertise of the person providing the training or mentoring (DTI General Code at 68). For an example of the practical application of the enterprise development scorecard, see Scholtz & Van Wyk (2010) at 7:5-7:6.

71 DTI General Code at 74.

72 Ss 2(a) and (f) of the BEE Act.

73 DTI General Code at 74.

74 Such as, underdeveloped areas and rural communities or geographic areas identified in the government's integrated sustainable rural development or urban renewal programmes.

75 The absence of astute legal drafting is further evident in par 3.2.4.8 of Code 700. This paragraph identifies the provision of training or mentoring to beneficiary communities which would empower them to increase their financial capacity as an SED contribution, subject to para 3.2.5.1 of the same Code. Unfortunately the Code does not contain a par 3.2.5.1. In the same vein, par 3.2.4.9 refers to a non-existing par 3.2.5.2.

76 Para 3.2.9 of Code 600 states that "providing training or mentoring to beneficiary communities by a business (Such contributions are measurable by quantifying the cost of time (excluding travel or commuting time) spent by staff or management of the business in carrying out such initiatives. A clear justification, commensurate with the seniority and the expertise of the trainer or mentor, must support any claim for time costs incurred)" is a recognisable enterprise development contribution, while par 3.2.5 of Code 700 states that "providing training or mentoring to beneficiary communities by a Measured Entity (Such contributions are measurable by quantifying the cost of time (excluding travel or commuting time) spent by staff or management of the business in carrying out such initiatives. A clear justification must support any claim for time costs incurred, commensurate with the seniority and the expertise of the trainer or mentor" is a recognisable SED contribution (emphasis added to stress the mere semantic distinction in the two paragraphs). For an example of the practical application of the socio-economic development Scorecard, see Scholtz & Van Wyk (2010) at 8:4-8:5.

77 DTI General Code at 92.

78 Wolmarans H & Sartorius K "Corporate Social Responsibility: The financial impact of black economic transactions in South Africa" (2009) 12 SAJEMS 180-193 at 189 and Heese K "Black economic empowerment in South Africa: A case study of non-inclusive stakeholder engagement" (2003) 12 Journal of Corporate Citizenship 93-101 at 100. Schneiderman (2009) at 262-270 also argues that BEE might be in contravention of various international investment rules.

79 The uncertainty regarding BEE rating has been addressed through legislative intervention. From 1 April 2011 BEE status certificates can only be issued by Verification Agencies accredited by the South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) or registered auditors approved by the Independent Regulatory Board of Auditors (IRBA) in accordance with the approval granted by the Department of Trade and Industry (Notice 1140, GG 33900 of 31 December 2010).

80 The current position is that the Verification Certificate recording the weighting points achieved in terms of the Scorecard, are valid for a period of only 12 months from date of issue (s 9(2)(c) of Notice 1140, GG 33900 of 31 December 2010).