Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.44 no.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v44i1.2875

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Religion, morality, science - And the (?) story of Homo sapiens

Danie Veldsman

Department of Systematic and Historical Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

From the most recent and directive dimensions of the (?) story of Homo sapiens (Hs), presented as a very limited overview and in broad outlines from an anthropological perspective, the focus will ultimately fall on three key concepts: ecosystems, niche construction and wisdom. These concepts in my academic opinion represent for our pursuit and further exploration on morality and religion from evolutionary perspectives the most important anthropological clues and directives. Against the background of two remarks: firstly, on the contextual state of the present science-religion discourses in South Africa and secondly, on the fluid and messy nature of the relationship between science-religion in contemporary discourses, the (no, a) messy story of Homo sapiens is told, incorporating the most recent post-Darwinian developments within evolutionary theories, highlighting the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) and the all-important four dimensions of inheritance that are embodied in these very three concepts.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: Reflection on the stories of Homo sapiens within cultural anthropological, theological and philosophical contexts in order to highlight directives and implications for the relationship between morality and religion within contemporary science-religion discourses.

Keywords: science-religion discourses; story of Homo sapiens; ecosystems; niche construction; wisdom.

Introduction

Stating that the story of Homo sapiens (Hs). can be told, harbours implicitly an overambitious and misleading entitlement for various reasons. The singular 'story' should be replaced by the plural 'stories' and then immediately and explicitly qualified as tentative, incomplete and permeated by wide-ranging (informed) speculation. Neither does the story of Hs exist (and most probably never will) nor can we claim in telling the stories that they are immunised against the epistemological pathology of speculation! Unfortunately not. That, however, does not have to deter us from at least trying our disciplinary best to engage with our own and wide-ranging histories creatively and imaginatively from the ever-increasing and growing knowledge, data, research findings on Hs. These stories unfold fascinatingly and insightfully, providing us with astonishing dimensions and interpretative clues for making sense of being human - albeit with the unavoidable acknowledgement of their shortcomings. And it is an urgency and necessity of making sense of being human that is powerfully driven by the fact that we are the last hominid standing (we are the only one of the entire 7 million year hominin experiments that made it) - and that indeed makes us special and worth exploring in spite of these shortcomings. Worth exploring because as bipedal primates, we are also more, much more. But to value, appreciate and understand the 'more', we have to take account of our stories - and they are - according to the Spanish-American primatologist and biological anthropologist Agustin Fuentes - messy stories of sticks and bones, muscles and guts, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and our circular response system, of behaviour - but then not detached from our history, culture and power.

My exposition and pursuit of a story of Hs within the context of contemporary science-religion discourses has a very specific and limited function, namely to only provide a very broad and general framework, a platform light, a tentative starting point for this Special Collection on morality and religion from a historical context. The Special Collection has our Project on Morality (abbreviated as ProMores 2022) as scholarly background - a project in which we have set ourselves as an ultimate objective to address an enormous vacuum with regard to ethical or moral reflection within our society, deeply characterised by pluriversality. If then deeply characterised by pluriversality, the immediate challenge that presents itself is to find a starting point for the reflective journey for filling the identified vacuum. With the hermeneutical echo of two philosophers - one from more than 2500 years ago - and another from just less than 50 years ago, I will start on the landscape or body scape from where I find myself, that is, deeply historically socially embedded in the South African context. The hermeneutical echo from the two philosophers - namely the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu (also known as Loazi and Lao Tse) and the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur - who, respectively, said:

千里之行, 始於足下 (Lao Tzu)

Meaning: a journey of a thousand Chinese miles starts beneath one's feet - or commonly rephrased as: …. begins with a single step. (c.f. Laozi, Wikipedia)

And:

d'où parlez-vous? (Paul Ricoeur)

Meaning: Where do you speak from? Quoted by the Irish philosopher Richard Kearney (2010:xi), the well-known student of Ricoeur.

I, therefore. start my reflective journey in telling a story of Hs beneath my (our) own South African feet in the near shadow of the Cradle of Humankind1 as internationally renowned paleontological hotspot (just more than 50 km away from us here in Pretoria) and in the not so quite near proximity of the radio telescope MeerKAT (Karoo Array Telescope in the Northern Cape)2 as cosmological hotspot in reflecting on and addressing an unsettling anomaly.

The first step beneath my feet will be two brief remarks: firstly, on the present contextual state of science-religion discourses in South Africa and on the fluid and messy nature of the contemporary discourses. Secondly, my big upright step as bipedal primate will be a brief and limited overview on a story of Hs - a messy, a very messy story - focussing specifically on the most recent and directive dimensions of our anthropological story and the newest developments within evolutionary theories.

I as anthropos (Greek: 'upward gazer'),3 as Hs (Latin: 'wise person')1 take my first step 'to move' (Latin: emovere, etymologically emotion) towards the anthropological narrative, I would like to share a personal interjective remark before I continue. The year 2022 has not been good on a personal level for the broader contextual science-religion discourses in South Africa. It has been a year in South Africa in which two leading South African theologians who in their own respective ways have been influential international pioneers on religion-science discourses, passed away - Wentzel van Huyssteen in February 2022 and Klaus Nürnberger in July 2022. Three years earlier (2019), the founder and chairperson of the South African Science and Religion Forum (SASRF), Cornel du Toit from the Research Institute for Theology and Religion, Unisa also passed away. If, however, we move beyond the personal loss of colleagues to the broader South African landscape or body scape of science-religion discourses from a historical and societal perspective, it unfortunately presents a very sad - almost fatalistic - state of affairs for many reasons and on many levels. It is from this sad (societal) state of affairs that I would like to find an interpretative way forward - perhaps best captured in the very words of Wentzel and Klaus combined: 'To transversally put together, the best insights from science and religion for the credibility of the latter and the integrity of the former'. I first turn to our societal context of the science-religion discourses and then to a story of Hs.

Contemporary science-religion discourses: Context and nature

Context

Just more than seven years ago, the South African systematic theologians Ernst Conradie and Cornel du Toit published an article as part of a volume of Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science on science-religion discourses worldwide. They presented an overview of the South African story on science-religion and the present state of reflection. In their presented story, its messiness - for reasons of its own - is confirmed, but also the dire straits it founds itself in.5 They state:

In spite of the paleontological importance of Southern Africa, a liberal constitution, a secular state, much money spent on education and some excellent scientists, South Africa does not have a scientifically informed populace. (Conradie & Du Toit 2015:456)

Their negative judgement is deeply embedded and informed by the political-social scars of the preceding apartheids era, the present religious profile, educational standards and the role of forms of knowledge outside the various sciences. The latter, namely forms of knowledge, labelled as Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) are important for putting together and making sense of our contextual story, especially against the distrust and outspoken labelling of science as racist rest of the West.6 With the strong emphasis on IKS - in relation to the critique of the Western way of doing science - as a social and cultural expression of the quest for identity and participation in a still very inequitable society, and for all the reasons mentioned above, it can be said that a strong pursuit of establishing the sciences in all spheres of the South African society is but in her shaky infant shoes. At the same time, it is thinly scattered over a few societal, institutional and organisational spheres and platforms. There are a few outstanding exceptions - but they are indeed few. The pursuit of constructive science-theology discourses is therefore also extremely scarce and restricted within the present South African context - and it showed very clearly in the societal sensemaking of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.7 I turn to a few general and directive remarks on the so-called 'troubled relationship' between religion and the sciences.

Nature of relationship

The deeper lying and more wide-spread lurking problem of the so-called 'troubled relationship'8 between religion and the sciences in South Africa, presents itself on the public surface with two very different faces: a face of opposition, distrust, ignorance and at the very same time, a challenging (nonneutral) ethical face of agency. Both social-cultural presented 'faces' are worrying and unearthing, and therefore needs serious critical attention and constructive engagement.9 Both 'faces' need to be addressed in an interdisciplinary manner, self-critically and constructively in all of our discourses on what best could and should be for human flourishing, acknowledging at the same time that both religion and the sciences (and their technological faces) represent two of the most dominant and shaping cultural forces in societies all over the world and therefore also in the South African society.10

Most of the contemporary religion or theology-science discourses that find their different ways into the public domain and on various public platforms are messy, fragile or destructive and discouraging. However, there are fortunately various societal-tertiary circles (universities, seminaries, colleges, academic societies, institutions, governmental committees and departments, Bible schools of faith communities, media platforms with informed debates) in which constructive discourses on the relationship of religion science are taking place and nurtured. But what are the deeper lying reasons for the messiness of the dialogue? I would like to make use of a rule that applies in the world of sport, namely soccer and rugby and apply it in a metaphoric sense to the dialogue. A player is considered offside - in soccer - if the player receives the ball while being 'beyond' the second last opponent or - to name but one example of offside in rugby - if the opposing player (number 9) to the player that feeds the scrum goes past the ball on the other side of the scrum to play the ball before the ball has come out of the scrum. How does it then metaphorically apply to the sciences and religious or theological reflection?

Both parties involved - science and religion - stand very guilty in this regard. Both have contributed vastly to the current emotional messiness between the two. Both have often (methodologically) played offside by making statements or claims in the past that they were not in a position to make, or that their respective methodologies do not allow them to make. Let me explain. Theological reflection in Europe has been baptised since medieval times as the queen of sciences. From this self-understanding as queen of the sciences, it took the self-imposed liberty in making statements about the physical world, about our biological make-up, as if the Bible or for that matter, any other holy text is a scientific handbook for dealing with such matters, and as if we as believers are in a position to say what can - or not - be regarded as (true) knowledge of everything and anything.

Charity - and in this instance, attending to the distrust and ignorance towards the science as well as the ethical challenges - begins at (our South African) homes. It begins beneath our 'own feet' as first step to our journey ahead in ultimately addressing the stark and unsettling anomaly: morality is indispensable in tackling the serious global problems we are faced with today. But, at the same time, we seemed to have lost our grip on what morality is. Taking on this anomaly, is deeply motivated and directed by the words of the South African mathematician and one of the world's leading theorists in cosmology, George Ellis (2006:5), who said that '.. [T]he science and religion debate can be important in emphasising the full dimension of humanity and in particular the crucial role of value systems that cannot be derived from science alone. Thus, apart from its role in deepening the understanding of religious faith in important ways, it can be an important integrative factor helping all humanity in the way we see ourselves and the universe in which we live, affecting our quality of life in a crucial way. It helps us to be 'fully human'.' But let us turn to our evolutionary Hs story of becoming 'fully human'.

Our story: Messy, very messy

Our ancestors did not run hand in hand through the daisies for 2 million years. They had conflicts; they fought, and sometimes killed one another. But most of the time they worked together, innovated and made things, created societies and collaborated to solve the problems the world threw at them. (Fuentes 2017:285)

We are primates, and we are hominids - and all that comes with that - but we are the strangest primates and the strangest hominids. And - as stated earlier in the introductory paragraph - be that as it may: we are the last hominid standing (we are the only one of the entire 7 million year hominin experiment that made it) - and that indeed makes us special and worth exploring. Worth exploring because as bipedal primates we are also more, much more. But to value, appreciate and understand the 'more', we have to take account of our story - and it is a messy story of sticks and bones, muscles and guts, DNA and our circular response system of behaviour - but then not detached from our history, culture and power.11 Our story as being human and being special, comes from the interface of neurobiology with perceptions, the histories, the social experiences, the languages and the daily lives of people. It entails a vast spectrum of disciplines, such as our evolutionary biology, genetics, cultural anthropology, primatology, archaeology, ecology, philosophy - and also theology! And from these wide-ranging fields, we harvest the power of the sciences to explore the deepest and most perplexing questions facing human kind.

Being special as human beings? I am asking, not stating: because we are the strongest, the survival fittest? Or because we are endowed with language, imagination, the ability for symbolic behaviour or cooperation? Perhaps caring/empathy? The question on our uniqueness can be answered from many perspectives and presents us in the contemporary discourses with fascinating detail. Fascinating detail from - to name but a few - the foundational work of the Dutch primatologist and ethologist Frans de Waal12 on primate cognition (cooperation, altruism, fairness), the American evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson13 on multilevel selection and trait-group, the American developmental and comparative psychologist Michael Tomasello14 on the origins of social cognition, the South African theologian Wentzel Van Huyssteen15 on human uniqueness, the American philosopher Holmes Rolston III on environmental ethics and animal rights within science-religion discourses, the British-born American paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall on human evolution (human fossil record and ecology) - and many more!

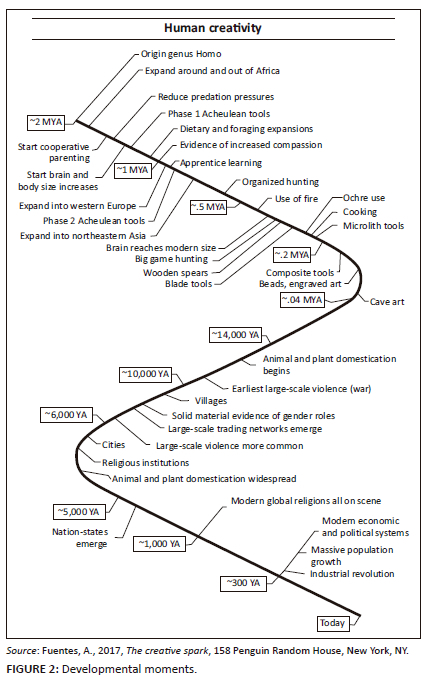

Figure 1 and Figure 2 at least give us some idea, some insightful guidelines and creative framework to the Hs timeline as well as evolutionary developments in broad outlines.

And with this timeline (Figure 1) comes fascinating developmental moments (demographic movements, on hunting and food, on sociality, animal and plant domestication, war and sexuality) (Figure 2).

As our specific and eventual aim is to trace and explore the stories of religion-morality emergence, I find the argumentative line of the Spanish-American cultural anthropologist Agustin Fuentes the most fruitful - not the most complete -for our further explorations. He takes as his evolutionary cue 'creativity' for the telling of a story of Hs and states:

Countless individuals' ability to think creatively is what led us to succeed as a species. And at the same time, the initial condition of any creative act is collaboration. (Fuentes 2017:2)

And:

The nature of humans' creative collaboration is multi-layered and varies widely. But one distinctively human capacity for shared intentionality coupled with our imagination is how we became who we are today. (Fuentes 2017:2)

Finally (in a rather long but beautiful quote), he states:

This cocktail of creativity and collaboration distinguishes our species - no other species has ever been able to do so well - and has propelled the development of our bodies, minds and cultures, both for good and bad. We are neither the nastiest species nor the nicest species. We are neither entirely untethered from our biological nature nor slavishly yoked to it. It's not our drive to reproduce, nor competition for mates, resources, or power, nor our propensity for caring for one another that has separated us from all other creatures. We are, first and foremost, the species singularly distinguished and shaped by creativity. This is the story of human evolution, of our past and current nature. (Fuentes 2017:2)

From our story of Hs, Fuentes argues (2017) that it is clear that we are not the species that is supremely good at being bad. Neither are we a species of super-cooperators, supremely good at being good. Nor is our nature shaped primarily by the happenstance of the environment we lived in and the challenges and opportunities they presented - that means, we are not a species that is still better adapted to traditional lives as hunter-gatherers than to modern mechanised, urbanised and tech-connected life. And lastly, our intelligence did not allow us to transcend the boundaries of biological evolution, to help rise above the pressures and limits of the natural environment and to mould the world to serve our purposes. All of these 'popular beliefs or convictions' are according to Fuentes (2017:4), gross simplifications and entertain some serious misunderstandings (although they have been instrumental in pushing our understanding of human nature forward).

For Fuentes (2017), the story of Hs is the epic tale of all epic tales. It is indeed the story of

… [A] group of highly vulnerable creatures - the favoured prey of a terrifying array of ferocious predators - who learnt better than any of their primate relatives to apply their ingenuity to devising ways of working together to survive; to invest their world with meaning and their lives with hope; and to reshape their world, thereby reshaping themselves. (p. 4)

Learnt better? Yes. To elude predators. To make and share stone tools. To make fire. To tell stories. To contend with shifts in climate. And at the heart of 'better' learning, we have the driving spirit of creative collaboration in order to deal with the challenges the world threw at them.

The basic story of Hs has changed dramatically over the last few decades. Recent discoveries and theoretical shifts in evolutionary theory and biology (e.g., how our environment and life experiences affect the functioning of our genes and bodies; new findings in the fossil record and ancient DNA) have brought about a changed basic story of humanity.

Fuentes (2017) again states:

A new synthesis demonstrates that humans acquired a distinctive set of neurological, physiological, and social skills that enabled us, starting from the earliest days, to work together and think together in order to purposefully cooperate. (p. 5)

And:

Acting in ways that benefitted the group, not just the individual or family, became increasingly common. This baseline of creative cooperation, the ability to get along, to help one another and have one another's back, and to think and communicate with one another with increasing prowess, transformed us into the beings that invented the technologies that supported large-scale societies and ultimately nations. This collaborative creativity also drove the development of religious belief and ethical systems and our production of masterful artwork. (p. 5)

To interpretatively capture the deep complexity of the developments and movements, Fuentes (2020) in an interview on 'This species moment' with Krista Tippett16 coins the term Holobiont. For him, it represents a basic concept that demonstrates in an extremely rigorous way, that organisms are, ourselves, things, cells that are made up of our own DNA and proteins and all of that - plus thousands, tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, of other organisms and their DNA, simultaneously. The insightful and very workable point that he makes is subsequently captured in the term ecosystems, that is, we are ourselves ecosystems. Fuentes elaborates, stating that the very functioning of neurobiological systems, of the hormones and enzymes circulating through arteries, guts and other organs, is tied to human social connections and relationships to others. And what is surprisingly new for him to work with, is that even things like the gut and like the gut biome is now described and taken as the 'second brain'! It means that over evolutionary time, the bodies, the structures of being human have adapted to and integrated themselves into the system where the social is everything. Fuentes (2020) refers in the interview to a great phrase by Tomasello: 'A fish is born expecting water; a human is born expecting culture'.

With the key concept of ecosystem, comes two other key concepts, namely of niche construction and wisdom within the latest developments on evolutionary processes (see Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (ESS) below). Reflection on these processes have moved away from simplistic, linear explanations of 'progress' or change via competition over time. No, our lead is to be taken from the ecosystem dynamics, entailing different processes of pushing, pulling, melding, shifting across the landscape - which according to Fuentes is rather messy. But within the messiness, we do not have a basic 'survival of the fittest' drive as has been popularised from Darwin onwards. No. For Fuentes, the whole competition on one end and cooperation on the other, represent a false dichotomy. For him, those things are not in opposition to one another but rather the fact that the best co-operators make the best competitors. Therefore, what has radically changed since Darwin?

In earlier articles (Veldsman 2020a, 2020d), I have extensively discussed the radical changes that have taken place as Darwin's original theory of evolution was formulated more than 160 years ago. The insightful evolvement is well captured in the ESS in which Darwin's theory is understood through a variety of lenses. But more importantly, it has been excitingly broadened. A broadening in which evolutionary theory has become much more than the inheritance of genes (cf. Veldsman 2020d:3-4). The most important implications that stems from EES are, as discussed earlier, the unmasking of 'the influential totalising discourses on the insistence of natural selection as a creative force as well as opened up new exciting interpretative anthropological horizons' (Veldsman 2020d:4). 'Becoming human' in Darwinian evolutionary terms entailed past fitness, potentials and survival mechanisms with natural and sexual selection as constitutive in change and adaptations for evolutionary success over a period as Van Huyssteen (2018:26) has showed convincingly. Precisely this totalising discourse has been radically revised and extensively broadened by scholars such as Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb (2005). They argue convincingly in Evolution in Four Dimensions that apart from genes, three other inheritance systems come into evolutionary play (cf. Veldsman 2020a:109ff, 2020d:4). Alongside the important genetic inheritance system, Jablonka and Lamb (cf. 2005:1-8) argue for three other inheritance systems that may also have causal roles in evolutionary change, namely epigenetic, behavioural and symbolic inheritance.17 From their emphasis, on more than simply genes as constitutive for evolutionary change, important implications flow for the broadening of traditional evolutionary theory (cf. Veldsman 2020d:4).

Evolution is now much more than simply the inheritance of genes. Behaviour and behavioural patterns are vehicles of the transmission of information and its transmission occurs through socially mediated learning (Veldsman 2020d:4). Language not only ensures symbolic inheritance but also the ability to engage in complex information transfer containing a high density of information (cf. Jablonka and Lamb 2005:193-231). The organisation, transferral and acquisition of information emerges as a special and distinct human trait (cf. Veldsman 2020d:4). And even more importantly, our distinctiveness for 'being human' finds characteristically expression in our ability to think and communicate through words and other types of symbols. Deeply embedded in the broadening of traditional evolutionary theory is niche construction (Veldsman 2020d:4). As convincingly argued by Fuentes (2016:13ff), it entails the insight that organisms are constructed in development, not simply programmed to develop by genes, and consequently do not evolve to fit into pre-existing environments but co-construct and co-evolve with their environments. The radical revision that comes from niche construction entails that the variation on which natural selection acts is not always random in origin or blind to function.18 As response to the conditions of life, a new heritable variation can arise (cf. Veldsman 2020d:4). The structure of our evolutionary landscapes is influenced by the ecological, technical and cultural niches that we as humans construct as Fuentes (2016:14) has showed eloquently.

For our reflection on morality and religion, the following important historical connection is to be noted especially with regard to religious imagination and the naturalness of religion: In the period from about 2.5 million to 12°000 years ago (the so-called Pleistocene period), we find a significant evolvement of increasing complexities regarding culture and social traditions, tool and manufacture, trade and the use of fire (Veldsman 2020d:4). Van Huyssteen (cf. 2018:28) adds in reference to Fuentes' article 'Human evolution, niche complexity and the emergence of a distinctively human imagination' to the evolvement of these increasing complexities enhanced infant survival, predator avoidance, increased habitat exploitation, and information transfer via material technologies. He insightfully summarises the implications:

All of these increasing complexities are tied directly to a rapidly evolving human cognition and social structure that require greater cooperative capabilities and coordination within human communities. Thinking of these developments as specific outcomes of a niche construction actually provides a mechanism, as well as a context, for the evolution of multifaceted response capabilities and coordination within communities. (Van Huyssteen 2018:28)

And:

(T)the emergence of language and a fully developed theory of mind with high levels of intentionality, empathy, moral awareness, symbolic thought, and social unity would be impossible without an extremely cooperative and mutually integrated social system in combination with enhanced cognitive and communicative capacities as our core adaptive niche. (Van Huyssteen 2018:29)

As convincingly argued by Fuentes and Van Huyssteen (cf. Veldsman 2020d:4), the key part of our evolutionary niches, and perhaps the best explanation for why our species succeeded and all other hominins went extinct, is a distinctively human imagination as intrinsic evolutionary force. What important insight can be deducted from the following concluding words of Van Huyssteen (2018) when he states:

Now existing in a landscape where the material and social elements have semiotic properties, and where communication and action can potentially be influenced by representations of both past and future behaviour, implies the possession of an imagination, and even something like hope, i.e., the expectation of future outcomes beyond the predictable?. (pp. 29-30)

The crucial important insight is the emphasis on a naturalness to human imagination and especially to religious imagination. It makes our engagement with the world in some ways truly distinct from any other animals (Veldsman 2020d:4).

Anthropological research also demonstrates that the deep ethnographic moment - how people actually are in the world - shapes the way they see, they perceive, they interact and those are evolutionarily relevant processes. And the important place and role of wisdom - from evolutionary perspectives, now a key concept - represent the capacity to learn, to understand and to experience, through perceptions and ways that facilitate different kinds of effectiveness and success in human lives. Therefore, becoming wise is not so much, necessarily, the accumulation of information, but it is how you engage information and how you use that with others and for others. Therefore, wisdom is this capacity to take knowledge and experience and do something with it and do something with it that offers the opportunity for change. Fuentes & Deanne-Drummond (2018a:1) neatly describes wisdom as 'the pattern (and ability) of successful complex decision-making in navigating social networks and dynamic niches in human communities'. It is suggested that much of the core development of human wisdom occurred with the evolutionary advent of symbolic thought and its correlated material evidence (Fuentes & Deane-Drummond 2018a:1).

Conclusion

From the three concepts within the EES that have been identified as constitutive markers of evolutionary developments, namely ecosystems, niche construction and wisdom, I turn to my fellow scholars to take the further steps on our ProMores 2022 journey. The re-telling of a story of Hs - as the last hominid standing - and taking on the task to put together the best insights from science and religion for the credibility of the latter and the integrity of the former in ultimately addressing that our ethical or moral concerns are to continue on and creatively explore that road of humanness that has made us special.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author's contributions

D.V. is the sole author of this article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and are the product of professional research. It does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institution, funder, agency, or that of the publisher. The author is responsible for this article's results, findings, and content.

References

African Union, 2015, Agenda 2063: The Africa we want, viewed 20 July 2022, from https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/3657-file-agenda2063_popular_version_en.pdf. [ Links ]

Conradie, E. & Du Toit, C., 2015, 'Knowledge, values, and beliefs in the South African context since 1948: An overview', Zygon 50, 455-479. https://doi.org/10.1111/zygo.12167 [ Links ]

Ellis, G., 2006, 'Why the science and religion dialogue matters', in F. Watts & K. Dutton (eds.), Why the science and religion dialogue matters: Voices from the international society for science and religion, Templeton Foundation Press, West Conshohocken, PA, pp. 3-26. [ Links ]

Fuentes, A., 2016, 'The extended evolutionary synthesis, ethnography, and the human niche. Toward an integrated anthropology', Current Anthropology 57(suppl. 13), s12-s26. https://doi.org/10.1086/685684 [ Links ]

Fuentes, A., 2017, The creative spark, Penguin Random House, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Fuentes, A., 2020, Interview on 'This species moment' with Krista Tippett, viewed 20 July 2022, from https://onbeing.org/programs/agustin-fuentes-this-species-moment. [ Links ]

Fuentes, A. & Deane-Drummond, C., 2018a, Evolution of wisdom: Major and minor keys, Center for Theology, Science, and Human Flourishing, University of Notre Dame. [ Links ]

Fuentes, A. & Deane-Drummond, 2018b, Introduction: Transdisciplinarity, evolution, and engaging wisdom, in Evolution of wisdom: Major and minor keys, Center for Theology, Science, and Human Flourishing, University of Notre Dame. [ Links ]

Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa, viewed 20 July 2022, from https://elifesciences.org/articles/09560. [ Links ]

Jablonka, E. & Lamb, M., 2005, Evolution in four dimensions: Genetic, epigenetic, behavioral, and symbolic variation in the history of life, IT Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Kearney, R., 2010, Anatheism, Colombia, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Kearney, R., 2021, Touch: Recovering our most vital sense, Columbia University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

'Laozi', Wikipedia, viewed 20 July 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laozi. [ Links ]

MeerKat, viewed 20 July 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MeerKAT. [ Links ]

Smithsonian's human origins program, viewed 20 July 2022, from https://humanorigins.si.edu/. [ Links ]

Southgate, C. (ed.), 2011, God, humanity and the cosmos: A textbook in religion and science. T&T Clark, Continuum. [ Links ]

Van Huyssteen, W., 2011, 'Foreword', in C. Southgate (ed.), God, humanity and the cosmos, T&T Clark, New York, NY, pp. xx-xxiv. [ Links ]

Van Huyssteen, W., 2018, 'Human origins and the emergence of a distinctively human imagination', in A. Fuentes & C. Deane-Drummond (eds.), Evolution of wisdom: Major and minor keys, Center for Theology, Science, and Human Flourishing, University of Notre Dame. [ Links ]

Veldsman, D.P., 2020a, 'From Harari to Harare: On mapping and theologically relating the Fourth Industrial revolution with human distinctiveness', in J.A. Van den Berg (ed.), Engaging the industrial revolution, SunPress, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Veldsman, D., 2020b, 'Science', in S.B. Agang (ed.), African public theology, Hippo Books, Langham, Carlisle, pp. 175-187. [ Links ]

Veldsman, D., 2020c, 'Coming face to face through narratives: evaluating from our evolutionary history the contemporary risk factors and their conceptualisation within a technologized society', Scriptura 119, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.7833/119-3-1770 [ Links ]

Veldsman, D., 2020d, 'From fides quarens intellectum to fides quarens sapientia: Revisiting and reformulating Anselmus' famous formulation within a contemporary theology-science perspective', Transilvania 9, 1-8. [ Links ]

Veldsman, D., 2021, 'Sanitation, vaccination and sanctification: A South African theological engagement with COVID-19', Dialog 2021, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/dial.12709 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Danie Veldsman

danie.veldsman@up.ac.za

Received: 17 Apr. 2023

Accepted: 17 Oct. 2023

Published: 18 Dec. 2023

Note: Special Collection: Morality in history.

1. The Cradle of Humankind is close to Krugersdorp, Gauteng. It was declared a World Heritage site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1999. It consists of a complex of limestone caves, called the Sterkfontein Caves. It is the site of the discovery of a 2.3-million-year-old fossil Australopithecus africanus (nicknamed 'Mrs. Ples'), found in 1947 by Robert Broom and John T. Robinson. The find helped corroborate the 1924 discovery of the juvenile Australopithecus africanus skull known as the 'Taung Child', by Raymond Dart, at Taung in the North West Province of South Africa. In close vicinity to the Sterkfontein caves, is the Rising Star Cave system. It contains the Dinaledi Chamber (chamber of stars), in which 15 fossil skeletons of an extinct species of hominin, provisionally named Homo naledi were discovered in October 2013. The latter represent the most extensive discovery of a single hominid species ever found in Africa. To read more about the fascinating story of the discovery and the work of the Wits paleoanthropologist Lee Berger, see: Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa, https://elifesciences.org/articles/09560

2. MeerKAT is the largest and most sensitive radio telescope in the world on MeerKAT and its impressive scientific significance, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MeerKAT.

3. See Richard Kearney (2021) on the interesting etymology of anthropos as 'upward gazer'.

4. The scientific labelling of Hs, that is 'wise person' is by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th-century work Systema Naturae.

5. In a more recent publication on 'Science' (2020) in African Public Theology, the South African systematic theologian Danie Veldsman also works from a very negative perspective on Africa with regard to the science-theology interaction. His exposition on science is structured with the concept of groaning: groaning for Africa, groaning with discernment and groaning together to act. The negativity stems from the contemporary situation in which most African countries are in many different ways deeply challenged over a vast spectrum of societal, economic and ecological groans, springing from numerous fountains ranging from the unearthing historical effects of colonisation to the present day intersectionality of bad and corrupt governance, economic injustices, environmental destruction (such as deforestation, soil erosion, desertification, wetland degradation, insect infestation) and unlimited power of external transnational corporations.

6. The importance of IKS, specifically for the South African context within the broader African context, necessitates a few elaborative remarks. In their discussion and appreciation of IKS, Conradie and Du Toit state that their choice to focus on IKS forms part of a broader initiative to recover African identity. It is to be recovered as the African identity has been tarnished and unearthed by various historical movements such as imperialism and colonialism but also by Africa's struggle with poverty and illiteracy. Perhaps the most important social-political reason for its tarnished identity is its relative unimportance in world events. Against this background, IKS must be seen and the story of Western science in Africa to be understood argue Conradie and Du Toit. IKS can be seen according to them as the body of knowledge available in a society. It consists of local and global, formal and informal dimensions of the societal body of knowledge. Importantly, the body of knowledge ultimately consists of a formal selection that is made from it. By means of the selected knowledge, members of the society are trained and equipped to participate in the society with the aim to contribute in a meaningful manner to their society. On this point, a crucial connection between IKS and Western science must be explored as the universality of science is often contrasted with local reception (see discussion thereof in Veldsman 2020b).

7. Some of the remarks during the pandemic period says it all: 'Vaccines are from the devil and God will destroy them all'; 'coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is but a bad flu'; 'No earthly president can tell us because of the pandemic not to gather as faith community on Sundays in the presence of our heavenly Father who is our shield and protection (Veldsman 2021:1ff); 'Science must fall - it's a racist rest of the West'. These are but a few opinions and remarks that have been emotionally raised on public platforms and social media in the South African society over the last 2 years on the worldwide raging pandemic and the valuation of the sciences on the African continent. Given the public outrage as critical responses to these voiced remarks and opinions, it can be said that they surely do not represent the viewpoints of the majority of South Africans. However, these negative remarks and opinions - with the very positive offshoot of the profiling of the crucial importance of the science-religion relationship - do reflect and represent a deeper lying lurking problem (especially in strongly religious circles) that is unfortunately more wide-spread.

8. For me, the most comprehensive and insightful discussion of the relationship between the sciences and religion and related issues can be found in God, Humanity and the Cosmos (2011) of which Christopher Southgate was the General Editor. Wentzel van Huyssteen (2011:xxiii) wrote the Foreword in which he laudably writes on the book: 'This book represents a strong and quite remarkable move beyond some of the ubiquitous generalities of the religion and science dialogue. It is the living proof that the theology and science conversation "works" if we contextualise it to specific issues in specific sciences and specific kind of theologies in specific religions. In this sense, this book will appeal to those of us with qualified postmodern sensibilities and goes beyond much of what is out there in the current literature. The student and teacher using this book will very soon learn the far-reaching educational impact of the fact that the evolving relationship between different sciences and any one religion will be different at any given time and will keep changing through history'.

9. The former, namely societal distrust and ignorance, relates to the importance and role of the sciences, and the influential significance of a constructive science-religion relationship for our well-being and for the flourishing of our communities. The latter, namely a challenging (nonneutral) ethical face, is the unqualified and uncritical convictions that all scientific interventions are simply and always unquestionably good, constructive and uplifting. That unfortunately is not the case. Especially the practical, everyday face of the sciences, namely technology with which we extensively engage on a daily basis and that reaches powerfully and directly into every cultural fibre of our being human, our communities and our societies (cf. African Union, 2015). This practical face of the sciences implies agency and has vast ethical implications with very often unforeseen and/or unintended destructive, unearthing and marginalising outcomes (cf. Veldsman 2020c).

10. To address the South African contemporary contextual presentation of the 'two faces' of distrust and/or ignorance and as ethical challenge is no easy task. The arduous task - embedded in complex entanglement - is woven together by a number of issues. At least three should be mentioned. (1) The two 'faces' are strongly pluriversally intertwined and are difficult to unravel - although each face do represent particular characteristics and problematic dimensions that are in need of painstaking discernment. It is therefore discernment that has to find its responsible ways in a society, deeply characterised by pluriversality. (2) Closely related to pluriversality that characterises our South African society is the outcry that the sciences are solely a product of Western modernity: a racist rest of the Modern West. To take the scientific knowledge on face value that is taught in our classrooms, lecture halls and pursued in our laboratories as solely a product of Western modernity stemming from Europe, is simply false. However, our scientific endeavours and their significance have to be 'decolonised', starting with understandings of the nature of the sciences and the teaching thereof. In the understanding and the teaching of the sciences, the misplaced viewpoints on the one hand and the academic arrogance, on the other hand, have both to be addressed. Addressed as conscious deconstruction of the unqualified conviction that Western rationality as it has found expression in the sciences is superior to any other expression of rationality, specifically non-European expressions of African rationalities. (3) There are clear stumbling blocks that hinders a constructive engagement between religious or theological reflection and the sciences. At least three important stumbling blocks are mistaken perspectives on the nature of scientific and religious or theological activities in relation to each other that can be identified. These mistaken perspectives - called 'all-too-familiar-clichés' by the British theologian John Polkinghorne and German theologian Michael Welker - entail the viewpoints that the sciences: (1) work only with facts, whereas theological reflection works only with feelings; (2) are objective, whereas theological reflection is subjective and (3) work only with things that can be seen, whereas theological reflection works only with unseen things. These identified stumbling blocks must be removed if we are to relate scientific and theological reflective activities with each other in a constructive manner. If not, then it only deepens the communicative gap of distrust and intensifies the emotional conflict between the two reflective fields.

11 . In what follows, I closely align myself with the work of the Spanish-American cultural anthropologist Agustin Fuentes. He has done work in primatology but specialises in biological and evolutionary anthropology, based most recently at Notre Dame and Princeton. He has delivered the prestigious Gifford Lectures (2018) and written and edited more than 20 books, mostly on human nature - from belief and creativity to race and wisdom. I find his work as scientist on the frontier of cultural anthropology refreshingly informative and creative.

12. Some of his most important and recent works: Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist (2022); Mama's Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us about Ourselves (2019); Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? (2016); The Age of Empathy: Nature's Lessons for a Kinder Society (2009); and Primates and Philosophers: How Morality Evolved (2006).

13. His most recent works are: The Neighbourhood Project: Using Evolution to Improve My City, One Block At A Time (2011); Pathological Altruism (2011) - as co-editor; Does Altruism Exist? Culture, Genes, and the Welfare of Others (2015); Complexity and Evolution: Toward a New Synthesis for Economics (2016); Evolution and Contextual Behavioral Science: An Integrated Framework for Understanding, Predicting, and Influencing Behavior (2018); This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution (2019); Prosocial: Using evolutionary science to build productive, equitable, and collaborative groups (2019); Darwin's Roadmap to the Curriculum: Evolutionary Studies in Higher Education (2019); A Life Informed by Evolution (2022).

14. Some of his most recent works: Why We Cooperate (2009); A Natural History of Human Thinking (2014); A Natural History of Human Morality (2016); Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny (2019); The Evolution of Agency: From Lizards to Humans (2022).

15. His three most influential works are Alone in the World? Human Uniqueness in Science and Theology (2006); The Shaping of Rationality: Toward Interdisciplinarity in Theology and Science (1999) and Duet or Duel? Theology and Science in a Postmodern World (1998).

16. The interview can be viewed at https://onbeing.org/programs/agustin-fuentes-this-species-moment.

17. Whereas genetic inheritance is the passing of genes, encoded in DNA, from one generation to the next, epigenetic inheritance affects aspects of systems in the body associated with development that can transfer from one generation to the next without having a specific root in the DNA. Furthermore, behavioural inheritance is the passing of behavioural actions and knowledge from one generation to the next, whereas symbolic inheritance is unique to humans and is the passing down of ideas, symbols and perceptions that influence the ways in which we live and use our bodies, which can potentially affect the transmission of biological information from one generation to the next (c.f. Fuentes 2017:6-7).

18. Fuentes (2017:10) neatly summarise niche construction as follow: 'Niche construction is the process of responding to the challenges and conflicts of the environment by reshaping the very pressures that the world places on (each of) us. A niche is the sum total of an organism's ways of being in the world - its ecology, its behaviour, and all the other aspects (and organisms) that make up its surroundings. In short, the niche is a combination of the ecology in which organisms lives and the way it makes a living'.