Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.41 no.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2029

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Reading Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) perspective

David T. Adamo

Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, Faculty of Human Science, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Psalm 90 stands at a critical juncture in the overall scheme of the Psalter. It is also the first Psalm of the small collection which constitutes Book IV of the Psalter. Psalm 90 can be regarded as one of the magisterial Psalms. Psalm 90 is unique in four ways: (1) Psalm 90 is the first Psalm of Book IV with new words after the unresolved ending of Book III; (2) it is the only Psalm with a superscription dedicated to Moses; (3) Psalm 90 is the most popular and attested text of the Bible according to archaeological facts; (4) the chapter is the theological heart of the Psalter with its emphasis on God's time and his reign. Unfortunately, however, many scholars have not paid much attention to how these Psalms are used as amulets, talismans, and medicine as attested by archaeological documents uncovered. The purpose of this article is to examine Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) context which has been supported by archaeological documents of Psalm 90 uncovered. Psalm 90 has been considered as a Psalm of protection, healing and success.

Intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary implications: 'Reading Psalm 90 in the African context' interprets Psalm 90 in the light of African culture. It deals with biblical studies, exegesis, African traditional religion, and African cultural practices using historical-critical and African biblical hermeneutical methodologies. The Euro-American way is challenged, and African biblical hermeneutics methodology presents a legitimate historical-critical methodology.

Keywords: Psalms; Old Testament; Yoruba; Africa.

Introduction

On Sunday 24 March 2019, during a preaching session, this author asked a congregation: Which is the most popular, most widely read, and most attested text of the Bible? The answers received were interesting. While some of them said Psalm 23, others said John 3:16. Others mentioned the Ten Commandments, Deuteronomy 6:4, and other passages. If the same question had been posed to readers of this article, perhaps they would have given the same answers as above. Kraus (2018:47-63) provided a survey of 'manifold and varied attestations of Psalm 90 by archaeological objects'. From this, one knows that Psalm 90 turns out to be the most popular, most widely read, and most attested biblical text. Though it may be a surprise to many people, Psalm 90 is the most frequently attested biblical text by archaeological objects (Kraus 2018:47-63). It has been confirmed that there are wall inscriptions, tomb chambers, medallions, rings, pendants, medals, wood tablets, sarcophagi, and papyri with either the complete text, or specific verses, or just the initial word(s) of Psalm 90 (Kraus 2018:47-63).1 Urbrock (1998) states:

Psalm 90 stands at a critical juncture in the overall scheme of the Psalter. It is the first Psalm of the small collection which constitutes Book IV of the Psalter. (pp. 26-29)

Psalm 90 is one of the magisterial compositions of the Psalms (Brueggemann 1984:110), and it is unique in four ways (Tanner 2014:685-696): (1) it is the first Psalm of Book IV with a new word after the unresolved ending of Book III; (2) it is the only Psalm with a superscription dedicated to Moses; (3) it is the most popular, most widely spread, and most attested text of the Bible according to archaeological facts, even though it is the shortest of Book IV (Kraus (2018:43-63); (4) it is the theological heart of the Psalter with its emphasis on God's time and reign.

What one calls the pivotal point of Psalm 90 is the goal of a heart of wisdom (v. 12). This is not referring to knowledge, skill, technique, or the capacity to control oneself, but the capacity to submit, relinquish, and acknowledge the decisive impingement of Yahweh on one's life. According to Beth N. Tanner (2014:695), the theme of Psalm 90 is that God is angry with the people for a long time.

The importance of writing this article is to demonstrate that Psalm 90, which is the most widely attested text of the Psalms and the Bible, has the greatest support for the use of the Bible in the African (Yoruba) context (Kraus 2018:1). The purpose of this article is to examine Psalm 90 critically and find out how it has supported the use of the Bible in African religious tradition. In other words, the writer wants to read and interpret Psalm 90 according to the African indigenous context.

African Biblical Hermeneutic methodology (Africentric) is used in this article. African Biblical Hermeneutics, or Africentric methodology is the rereading of the biblical texts with the African worldview or African culture and tradition. It is the bringing of African life interest into the interpretation of the biblical text and assigning it a dominant role in interpretation (Adamo 2015a:31-52). It can be called African cultural hermeneutics, or African transformational hermeneutics (Adamo 2015a:31-52; 2015b:1-13). Most of the time, this Africentric approach of the interpretation of the Psalter has not received adequate attention or is neglected not only by the Euro-American scholars, but also by the African scholars who are mostly trained in the Euro-American scholarship.

To achieve the above purpose, this article will discuss the contemporary Euro-American literary analysis of Psalm 90, the reading and interpreting of Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) context, and evidence of using Psalm 90 as talismans, charms, and medicine.

Translation of Psalm 90

A Prayer of Moses, the man of God.

1 Lord, you have been our dwelling place in all generations.

2 Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever you had formed the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God.

3 You turn us back to dust, and say, 'Turn back, you mortals'.

4 For a thousand years in your sight are like yesterday when it is past, or like a watch in the night.

5 You sweep them away; they are like a dream, like grass that is renewed in the morning;

6 in the morning it flourishes and is renewed; in the evening it fades and withers.

7 For we are consumed by your anger; by your wrath we are overwhelmed.

8 You have set our iniquities before you, our secret sins in the light of your countenance.

9 For all our days pass away under your wrath; our years come to an end like a sigh.

10 The days of our life are seventy years, or perhaps eighty, if we are strong; even then their span is only toil and trouble; they are soon gone, and we fly away.

11 Who considers the power of your anger? Your wrath is as great as the fear that is due you.

12 So teach us to count our days that we may gain a wise heart.

13 Turn, O Lord! How long? Have compassion on your servants!

14 Satisfy us in the morning with your steadfast love, so that we may rejoice and be glad all our days.

15 Make us glad as many days as you have afflicted us, and as many years as we have seen evil.

16 Let your work be manifest to your servants, and your glorious power to their children.

17 Let the favor of the Lord our God be upon us, and prosper for us the work of our hands - O prosper the work of our hands! (NRSV)

Contemporary western literary analysis of Psalm 90

According to Jens (1995), Psalm 90 is:

A puzzling text, contradictory and dark, hopeful and somber, merciless, and gentle. A song of dying and a word of life - a Psalm marred equally by fear and trust, of terrible death and tender friendliness, lament and praise, wrathful judgment and hymnic eulogy. (p. 177)

The composition of Psalm 90 is written for a specific occasion (prayer) in the life of the Hebrew community. It is also written in the apocalyptic context as a prayer for knowing 'the divine secret of how long the tribulation will last' (Clifford 2000:60). Even though it was originally a prayer for knowing the divine secret of the end of the punishment, it is certain that when this Psalm became part of Israel's hymns and a standard part of its temple liturgy, it was prayed and sung as a community lament and prayer to express the plea that God would establish Israel and end its tribulation (Boring 2001:121).

Psalm 90 is considered a theological prayer addressed to God in the second person (Boring 2001:111-118). This Psalm has also been read as 'a wisdom reflection, a wisdom prayer, or a wisdom lament over the past' (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:417). The psalmist confesses the brevity and littleness of human life which is the general biblical perspective on humanity. The main theology of Psalm 90 is that of the brevity and smallness, frailty, the guilt of humankind, and the grace and mercy of Yahweh from generation to generation (Boring 2001:111-118). Scholars have said that there is no petition against enemies in Psalm 90 (Boring 2001:111-118).

Psalm 90 takes a crucial place in the entire Psalter and is the theological heart of the Psalter (McCann Jr 1993:155). It is the only book that is attributed to Moses, the man of God. Moses became a paradigm for Israel's and humanity's (McCann Jr 1993:155).

According to Tanner (2014:595-696), Psalm 90 has four stanzas and it starts with praise and the reason why God should repent and change the current situation. The following are the stanzas:

-

Praise of the eternal God (vv. 1-2)

-

Remember how short human life is (vv. 3-6)

-

God's great anger (vv. 7-12)

-

A relationship restored (vv. 13-17)

However, according to Clifford (2003:6), Psalm 90 has three parts instead of the four suggested by Tanner:

-

Eternal God versus short-lived humans (vv. 1-6)

-

Divine wrath without limit of time (vv. 7-12)

-

Prayer for restoration (vv. 13-17)

Brueggemann and Bellinger Jr (2014:391) see two main parts in the structure of Psalm 90, namely Divine permanence and human frailty (v. 12), and the petition (vv. 13-17).

According to Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:418), Psalm 90 has an artistic structure. The vocabulary used in Psalm 90:11-12 betrays the wisdom character of the Psalm. The words יראה ,ידעִ are used in combination with the divine name יהוה in verse 11 (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:418). Other wisdom vocabularies that appear in Psalm 90 is לבב and חכמה (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:418). This wisdom lament is theologically related to the books of Job, Qoheleth, and Proverbs. Bullmore (2016:289-292) also considers Psalm 90 as timeless ancient wisdom and the only Psalm dedicated to Moses. While Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:420) see the entire Psalm 90 as the original work of a single poet, others believe in its two-stage origin. In other words, verses 1-12 are the original, and verses 13-17 are an addition or expansion (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:420). It is difficult to deny the wisdom nature of Psalm 90, in light of the wisdom vocabularies mentioned above.

In verse 1a the superscription gives the Psalm the authority of a prayer petition by Moses, the man of God. This is the only Psalm with such a superscription in the entire Psalter. The superscription, 'The prayer of Moses, the man of God', is probably the editor's signature device (Alter 2007:317) which gives the book the authority needed as 'a prayer of petition' (Alter 2007:317).

Most of the Psalms have superscriptions attributed to about eight different persons, but Psalm 90 is the only Psalm with a superscription referring to Moses as the man of God. This is the title in the oldest Hebrew text that is available to us and the Jewish community accepted it as part of the canonical text (Boring 2002:119-128). It appears that this title is not original even though almost all English translations accepted it.2 I believe that Boring (2002:119-128) is correct by saying that the addition of the titles was an act of interpreting the text to give it a specific meaning.

Modern scholars have begun to emphasise the value and importance of the arrangement of the Psalter, the value of the superscriptions that are added to the Psalms, and the relationship of the different sections of the Psalms as far as the five books of the Psalter, as we have them now (Mournet 2011:66-79). Wilson (1986:87) maintained that the difference between Books I-III and Books IV-V has to do with the separate redactional editorial behind these sections of the Psalter. He believes that Books IV-V are later additions to Books I-III. Psalms I-III have an emphasis on the Davidic dynasty, but Books IV-V have a dramatic shift by having Book IV ascribed to Moses. There are seven references to Moses in Book IV and only one in the rest of the entire Psalter (Ps 77:21).

Psalm 90 is the beginning of Book IV (Ps 90-106). It looks back to the Psalm before it (Ps 89) by its references to the brevity of life (Ps 90:3-6), divine wrath, and the question of time. It also looks forward to Psalm 91 by its reference to the 'dwelling place' (Clifford 2003:96).3

In Ps 90:4, living a thousand years is like a day in God's sight. It will be like next to nothing as far as the existence of God is concerned. Unlike God, human beings are not everlasting (Alter 2007:318). In verse 4 there is also an eloquent triadic structure. The psalmist moves from 'a thousand years' to 'a passing day', to 'a watch in the night', which makes the vision of time seen from God's end of the telescope (Alter 2007:318).

Psalm 90 portrays the ephemeral human beings who are little more than a dream or asleep (v. 5), who flourish like quickly-withering grass (vv. 5-6), and who vanish after their miserable 70 or 80 years (if they live that long). There is a special appeal, not an admission of guilt or innocence, at the heart of the appeal. But it is an appeal to Yahweh to consider whether it will not be fair to just give some relief to these tiny creatures of his. Have we not suffered long enough? This seems to be the underlying appeal here. The author seems to be saying, since a thousand years is like a day or less, why do the offences of our tiny lifespan catch your attention and make you angry?

The contrast between the human and the divine is central in verse 1-6. Verse 7 is an important verse with the topic of divine wrath, which becomes a major theme in the Psalm, and which is a symbol of God's withdrawal. It is not talking about occasional anger directed toward us. God is talking about a decision he has made since. This is the judgement that God made in his righteousness, the result of which is our mortality and brevity of lives.

In the context of the brevity of life, verses 7-12 complain about how humans are overwhelmed by Yahweh's wrath. In verse 9 the human being is in pain under divine anger. The life of a human being is set to be 70 or 80 years at best, yet those years are full of trouble and woe and in a twinkling of an eye, life disappears.4 Then the section ends with a petition for wisdom to be able to reflect on such brevity of life and live it fully. Based on the Akkadian and Ugaritic usage of counting life, Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:418) believe that to 'count the days' is not to think about the span of life but has to do with 'a specific preset time'. It is therefore not a plea to teach human beings wisdom to be able to count the days of one's life, but to be able to 'accurately tally the days of God's wrath so that they will be able to understand that there is indeed an end to life' (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:418; Tanner 2014:695).

While this Psalm begins with the omnipotence of God (vv. 1-4) and then continues with a meditation on the brevity and fragility of human life (vv. 5-12), verses 13-17, which form the last section of the chapter, are entirely a petition. The previous verses (vv. 1-12) have been the background for the petition to soften God's heart to hear the petition of the people. Verse 13 is a formulaic lament for restoration with 'Turn, O Lord! How long? Have compassion on your servants!' In this verse, two important Hebrew terms are significant as they appear together: שׁוב and נחם. This is the only time in the Psalter they appear together (Mournet 2011:77).5 The importance of the appearance of those two Hebrew words together here is that it gives Israel hope that if they repent God can still repent of his judgement as he did for Moses.

Verses 11-12 are the centre of the Psalm. It is regarded as the conclusion of the primary and complaint section (vv. 1-12). According to Clifford (2003:97), the poem is not 'a meditation on human transience' as commonly supposed, and therefore verses 11-12 are not a 'prayer for a deeper realization of mortality and frailty so that one may be submissive to God'. Rather, the suffering community wants to know how long the suffering will last. According to him (Clifford 2003), verses 11 and 12 can be paraphrased as follows:

No one knows the duration (the full extent) of your anger … / Let us know how to compute accurately/ our days (of our affliction); Let us bring that knowledge (into) our minds,

Knowing the duration of the affliction helps one to bear it. (p. 97)

In verse 11 the psalmist poses a double question: 'Who considers the power of your anger?' The psalmist is in a way calling into question, like Ecclesiastes, the logic of death as developed in the above section. 'Who considers the power of your anger?' also tries to turn the problem of the wrath of God back to God himself, and then appeals to God who is the teacher of life, without asking for rescue from the problem of death. Instead he petitions for the right wisdom about life and the ability to deal with the knowledge of death (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:423). The knowledge of the limitedness of time that is allotted to every person may help one to know the immense value of every single day and the ability to deal with the reality and challenges of life, and consider each day as a gift of the Creator.

It is quite interesting to read how, in a situation of an extreme problem, the psalmist turns not to humans, but to God. God alone is the one who can teach how to count the days and not to think of death, which is certain, but of life that is uncertain and requires meaningful order. While mortality is accepted without contradiction, the futility of human action is put into question.

Verse 13 is the only place where God's proper name, Yahweh, is mentioned in Psalm 90. Then it is followed in verses 14, 15, and 16 with a series of three pairs of imperatives or jussives (Brueggemann 1984):

Satisfy / make us glad

Let us see / let your favour

Establish / establish. (p. 113)

It seems that the three imperatives challenge the idea in verses 1-12 which assume that God is eternal, and humankind is transitory and cannot change (Brueggemann 1984:113). Verses 13-17 conclude by moving to the traditional Psalmic petition style with the hope of restoring the relationship with Yahweh as 'a dwelling place'.

In verse 17, the last verse is an inclusion, 'the favour of the Lord reverses the order of the words and the consonant in verse 1': 'Lord … dwelling place' which brings the poem to a close. The 'inclusio' unifies the entire Psalm and redirects the reader to the beginning in verse 1.

Reading Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) context

The worldview of Africa and Africans is remarkably different from that of Euro-Americans, especially when it comes to life interest and situation. In Africa and among the African people, three major concerns in life exist and dominate. The first is everyday protection, the second is everyday health, and the third is how to achieve everyday success. Among the Yoruba people, nothing happens naturally. The cause of lack of protection, even death, bad health or diseases, and the lack of success is the enemy, called ota in the Yoruba language (Adamo 2001:32-42). Yoruba people believe that everyone has at least an ota, known or unknown. They are responsible for every evil thing that happens. Yoruba people must constantly protect themselves from ota. It is important to discuss protection in Yoruba tradition, before the discussion of how African Yoruba Christians interpret the book of Psalms as a book of protection (Adamo 2001:32-42). This will inform our understanding of why Psalm 90 is read and interpreted as talismans, charms, and medicine for protection.

Protection in Africa (Yoruba) religious tradition6

Protection in African (Yoruba) indigenous religion is taken with all seriousness because of the belief that enemies are everywhere (Adamo 2005:69-88). Potent words, medicine, and talismans are the three main ways of dealing with protection (so called incantations - ofo or modaritkan, or ogede). What is ofo, modarikan, or ogede? I believe that it is important to understand what ofo is to know the reason why the Yoruba people of Nigeria approach the Bible the way they do. According to Olatunji (1984:139), ofo is 'a restricted poetic form, cultic, and mystical in its expectation'. Ofo is the verbal aspect of the magical act among the Yoruba people. The others are rites, charms, and medicine. The Yoruba people consider ofo as a source of the mystical power and the attainment of metaphysical manhood that is jealously guarded by those who have obtained it from a native priest or medicine man. Immediately when it is obtained, it becomes the exclusive property of the owner and is jealously guarded (Olatunji 1984:139). Most of the time the potent words are not revealed to another person, because revealing it means laying oneself bare to the attack of presumed enemies. This can also be considered 'a magic formula, sentences uttered very fast with the normal voice of ordinary speech' (Olatunji 1984:139). Through the use of this magic, human beings attempt to control both the natural and the supernatural world around them, and subject them to their will. This is the utterance of words according to specific formulas.

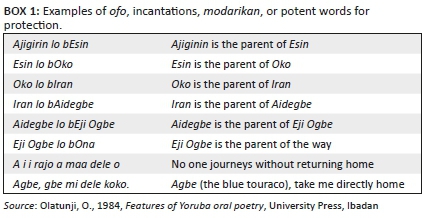

There are four specific beliefs underlying ofo, ogede, or incantation. The first one is the belief in sympathies, animate or inanimate, and inhuman or supra-human beings. The second belief is the belief in the magic of names. This is the firm belief of the Yoruba people that every person, thing, animate and inanimate, even divinities, has primordial names, and whoever knows these names can control their bearers and the power immanent in them (Olatunji 1984:141). The third belief underlying the Yoruba ofo, ogede, or incantation is the belief in the power of knowing the origin and the primeval experiences of incantatory agents. It is believed that the person who knows such origins will be able to control these agents. The fourth belief is the belief in the power of oro (words). This is the reason why incantations are also called oro (words) or ofo (speaking). All these beliefs influence the memorisation, reading, and interpretation of the Bible (see Box 1).

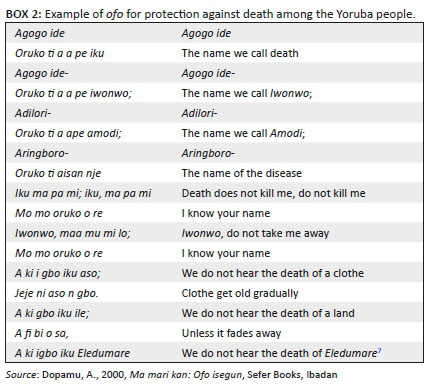

There is a firm belief among the Yoruba people that if the above ofo is memorised and recited over and over, the reciter is protected, no matter how dangerous the journey. What is done above with memorisation and recitation and naming the origin of the road where one is travelling, is to guarantee safety no matter how dangerous the road may be (see Box 2).

Even though the Yoruba people believe that death is a necessary end, they still struggle to prevent it with ofo and medicine, especially untimely death.

Psalm 90 as a Psalm of protection, healing, and success

Before the advent of Christianity, African (Yoruba) people lived in the above tradition where ogede or ofo, incantations, traditional medicine, tira, or talismans were very prevalent.8 These are means of solving various problems such as poverty, diseases, protection, and others. At the advent of Christianity in Africa (Yoruba land), the Yoruba people enthusiastically accepted Christianity. They were told that all the above practices of ofo, incantations, were forbidden by Christianity. They burnt their medicine, talismans, and charms in good faith with the hope that there must be a substitute in the new religion. However, when there was no substitute, other non-Christian colleagues mocked them by calling them 'women' because they had no charm, talisman, and ofo for protection (Adamo 2001:67-81).

One of the greatest things that missionary Christianity did for Africans (Yoruba), is to translate and teach Africans how to read the Bible in their languages and dialects. The Africans greatly admired the courage and faith of the Euro-American missionaries who came from their far countries to preach Christianity. As they faithfully and critically watched the missionaries, they were made to believe that the missionaries must have not come from so far to the jungle of Africa and the midst of ferocious witches and wizards without protection. They observed that the greatest thing they held firmly as precious documents was the Holy Bible, which they taught faithfully and fearfully as the Word of God. Africans (Yoruba) read and searched the Holy Bible for that secret power that gave the missionaries the protection, healing, and success which the missionaries presumably refused to teach them (Adamo 2001:72-73). As the Yoruba Indigenous Churches read and searched the Holy Bible, they discovered that there are stories of divine miraculous protection, miraculous healing through words, herbs, and successes both in the Old and New Testament Bible.9 The discovery of Hebrews 4:12, which says that the word of God is powerful and sharper than the two-edged sword, was an encouragement to the African (Yoruba) Christians to use the word of God as ofo.

Because the Yoruba Christians believed in the absolute power of the word that the Holy Bible teaches protection, healing and success, they started practicing what they believed. As a result, the persecution started from the mainline missionary churches to which they belonged. The persecution led to the separation of the African indigenous churches so that they would be able to practice their form of Christianity using a combination of the Bible and African (Yoruba) traditional methodologies.10 They read the Bible for their life interest, that is what concerns them most in life-protection, healing, and success. The separation from the mainline missionary churches gave the African indigenous churches the freedom to use the Bible as ofo, instead of going to native priests to obtain words, charms, and medicine. The book of Psalms became their favourite part of the Bible, because of its resemblance to ofo. Just like other psalms, Psalm 90 is divided into three major parts as a protective, therapeutic, and success Psalm. However, the entire chapter can be read, recited, and inscribed for protection, healing, and success.

Psalm 90 as a Psalm of protection

Psalm 90:1-3 can be considered a Psalm of protection because the content has to do with protection. In verse 1, the author affirms that God is our 'dwelling place'. According to Brueggemann (1984:111), this first affirmation is extraordinary because it affirms that the speaker is not homeless; he cannot provide for his accommodation himself, because it is a gift of God; the home is not a place but a person. Brueggemann (1984:112) also calls Psalm 90 a Psalm of disorientation because it is 'intensified' with references to 'anger' (v. 7), 'iniquities, sin' (v. 8), 'wrath' (v. 9), 'anger, wrath' (v. 11). Psalm 90 is about who God is. God is our security, rest, and refuge. The affirmation is not only our security, but God is unchangeable from generation to generation. Verse 2 emphasises that from everlasting to everlasting he is God, before the mountains were created. In other words, the entire world belongs to God, not only Zion. The author then contrasts Yahweh's unchangeability with human mortality (vv. 1-3). God as security is certain and sure.

One of the reasons why African interpreters, mainly the African Indigenous Churches, considered Psalm 90 as a Psalm of protection, is not only because of the African (Yoruba) indigenous tradition of making protection from enemies paramount in life, but also because of the content of verses 1-3, as discussed above.

The African Indigenous Churches, such as Cherubim and Seraphim, Celestial Church of Christ, Christ Apostolic Church and others, were the main group involved in such practices at first, but now almost all the mainline missionary churches among the Yoruba people have joined (Mepaiyeda 2013:32-34). Based on the belief in the power of words (ofo, oro) which was passed on to their Christianity from their African (Yoruba) religious tradition, the words of Psalm 90 become ofo or incantation. Based on that belief, the words of Psalm 90 are written on parchments, worn on the neck, hung on the doorposts, or kept under pillows overnight for protection.11

According to the Prophet Tarnner (2007:27), Psalm 90 can be used against evil spirits and for a dangerous journey, to prevent the attack of robbers and marauders. Prophet Ogunfuye seems to specialise in the use of the Bible, especially the book of Psalms for protection, healing, and success. According to him (Ogunfuye 1988:1), Psalm 90 can be recited with a specific prayer written on parchments.

Psalm 90 is regarded to be one of the Psalms to be memorised and recited every morning and evening for a safe trip. According to an anonymous writer, this Psalm can be read with other Psalms such as 2, 64 and 124 when embarking on a journey for safety. Psalms 90, 2, 64, and 124 are considered protective Psalms while travelling on water and dangerous roads because they are considered potent words and appropriate for protection as bulletproof for 'hunters when used with the Holy name JAH' (Anon. n.d.:24-29; Ogunfuye n.d.:40).

Reading Psalm 90 therapeutically

The understanding of healing in African religious tradition will possibly increase the readers' understanding of how and why Africans (Yoruba) read and interpret Psalm 90 therapeutically.

Healing in African (Yoruba) tradition is a corporate matter. Good health in African indigenous tradition is remarkably different from that of the western world. While the western world defines good health as an absence of diseases or infirmities, African (Yoruba) concept concerns the state of total physical, mental and social wellbeing as a result of maintaining a good relationship and good harmony, with not only human beings but also with nature, spirits, and divinities. Good health involves physical, psychological, spiritual and environmental conditions. In African religion, bad health can be classified into three categories: the natural or physical, the supernatural, and the mystical (Adamo 2001:48). The natural and physical have to do with mere dysfunctioning of the physical body and normally respond to medicine quickly. The supernatural and the mystical diseases are the ones caused by witches and wizards and by breaking taboos, the negligence of responsibilities of ancestors, and disharmony with fellow human beings. This is the most difficult to treat, because it involves the use of herbs, rituals, confessions, sacrifices and special restoration with God, divinities, and the environment (Adamo 2001:48).

Before the advent of Christianity and western medicine, African (Yoruba) people had developed ways of dealing with diseases. They had developed the ways of rescuing themselves from these types of diseases with herbs, powerful potent words, living and non-living materials such as water, fasting, prayers, laying of hands, rituals, and restoration of people (Adamo 2001:47-62).

Box 3 shows examples of the use of materials and potent words for healing in African (Yoruba) indigenous tradition.

To relieve a woman in hard labour, the African (Yoruba) people have numerous medicines to quicken the discharge of the placenta to enable easy birth. A prescription for this medicine is as follows (Dopamu 1982):

[Take] a snake that has swallowed something. Remove and burn what has been swallowed with alligator pepper. The powder must be put in a small gourd (ado) and covered with white leather. The snake itself must be burnt separately with alligator pepper and cowry, put in another small gourd, and covered with red leather. When a woman is in labor stage, she must be given (with a left hand and received with a left hand), the powder in the small gourd with red leather to drink with maize pap (eko). After a few minutes, the powder in the small gourd covered with the white leather should be done with the same method. The baby and the placenta will come immediately. (p. 37)

Psalm 90:4-12 is considered a therapeutic Psalm not only because of the African (Yoruba) tradition, but also because of the contents which resemble the African situation and African (Yoruba) understanding of existence. Psalms 90:4-12 can be recited, inscribed on a parchment, or read into the water for healing diseases.

The same method of healing that the African (Yoruba) indigenous people use has been transferred to the use of the Bible. In other words, African (Yoruba) indigenous traditional methods of healing became a preparation for African Christian healing. At the discovery of many Bible passages that record miraculous healing by words, actions, herbs, and other means in the Bible, the African Indigenous Churches started using the reading, memorisation, and recitation of Bible passages with the combination of actions and other means for healing. As mentioned above, the book of Psalms became the most frequently used book for such a purpose. The book of Psalms, with the combination of faith in the power of God to heal, was used. According to Adamo (2001:54; 2015:1-13b), the African (Yoruba) indigenous Christians believe that virtually all types of illnesses are curable with the combination of reading, memorisation, and inscribing the words of God in parchments, on clothes, on houses, vehicles and even bodies, with a combination of African materials.

A Norwegian Old Testament scholar, Knut Holter, who came to Nigeria for research on using the Psalms to heal in African indigenous churches in Nigeria, mentioned how a Nigerian prophet used the reading of the book of Psalms to heal a barren woman. Below is the testimony of a woman who got the assistance from the prophet (Holter 2014):

The daughter had been married for more than ten years without getting pregnant, and the mother went to see the prophet. He read Psalms into some oil and gave instructions about how the oil should be sent to North America and how the daughter should use it. This happened in December 1999. In June 2000 the daughter got pregnant, and nine months later she gave birth to a healthy boy. (pp. 428-443)

Reading Psalm 90 as a Psalm of success

A brief discussion of the concept of success in Africa (Yoruba) religious tradition is important, before the actual presentation of reading and interpreting the Psalm as a Psalm of success.

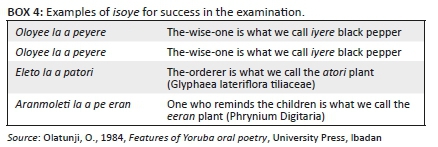

The meaning and nature of success in African religious tradition are remarkably different from that of the western world. In African (Yoruba) religious tradition success means getting rich, passing examinations, marrying many wives, good sales, winning court cases, loving a woman, securing employment. The means of enhancing success in life is not only hard work. It includes the use of potent words, doing medicine, and offering sacrifices and other mysterious means (Olatunji 1984:143). In an African tradition, passing an examination is considered a success. There are also potent words to aid memory, called isoye (quickening the memory) in the Yoruba language. Methods to pass examinations are shown in Box 4.

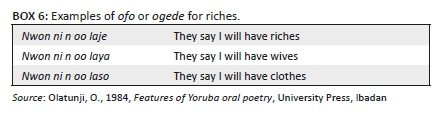

It is believed that the recitation or inscribing so many times will make one very rich (Box 5 and Box 6).

The recitation, memorisation, and inscribing of ofo will always bring success in any examination.15

There are many ofo or incantations for getting rich (see Boxes 5 and 6).

Reading the Bible for success

The three pairs of series of imperatives (satisfy or make us glad [v. 14]; let us see or let your favour [v. 15], and establish or establish [v. 16]) that have been mentioned above (Brueggemann 1984:113) are important literary evidence for making Psalm 90 a success Psalm. Success has something to do with favour, establishing, and satisfying a person in life.

By linking the prayer in Psalm 90:13 with the prayer of Moses in the Exodus narrative (when Moses intercedes for the Israelites and the wrath, and punishment of God is averted) the psalmist is suggesting that God is a refuge and ultimate king who can still get involved personally in the continuing survival of his people. As a result of the continuing intercession of God's people, God can still נחם or change his anger and judgement and heal nations and the individual. It means that the hope of the psalmist in Psalm 90 can become the hope of the African (Yoruba) Christians as they recite or inscribe it as talismans by appropriating it.

Verses 13-17 conclude by moving to the traditional psalmic petition style with the hope of restoring the relationship with Yahweh as a 'dwelling place'. The petition for a plea for God to return and have compassion with the people is followed by the question, 'How long?' In verse 15, the petition is to Yahweh to grant the community as many days and years of joy as the days and years of their travail. The petition is for divine intervention for the present generation and the next.

The plea of verse 14 is a return to hesed (compassion or love). In verse 15 there is a plea that the days of joy be made equal to the days of suffering. Verse 16 requests God's works and splendour for the people.

'God is faithful, eternal and unchangeable in turning toward humanity; one's allotted time can be meaningful, purposeful, joyful, and enduring' (McCann Jr 1993:61). The word in verse 17 is an appeal for a special blessing and the revelation of Yahweh's favour.

In many Aladura churches, the Psalm texts are deemed potent words (incantations). The reciting of divine names and sacred objects are used within a prescribed rite to achieve the desired purpose. E.O. Nwokoro (1994:6) of the Aladura Church in his booklet, The mystic power of the Psalms, prescribed various Psalms to be read in a certain way to achieve success in business. Psalm 90 can be considered as a model of prayer for people who have patiently waited for God for prosperity for the community.

Evidence of using Psalm 90 as talismans, charms, and medicines

What is remarkable, is that Psalm 90 is the most widely attested text of the book of Psalms that have been used as talismans, charms, and medicines like the way the indigenous African (Yoruba) Christians use the Bible (Kraus 2018:47-63). According to Kraus (2018:47-63), a considerable number of papyri folded and used as amulets and possibly worn for protection are available. A group of 12 known wood tablets called Bous tablets exists for protection against evil powers (Kraus 2018:43-63). Psalm 90: 1-2, with its wishes for God as the dwelling place and the creator from everlasting to everlasting, is favourable for use as a Psalm of protection. These verses are especially suited for writing on the door lintel, as are found in 'Syria-crosses, sun-like shape-non-textual elements' (Kraus 2018:54). 'The protective and hopeful character of the text of Psalm 90 LLX makes it perfect to be written for the deceased' (Kraus 2018:54) on the tomb chambers and sarcophagi. The necropolis of Gabbari in the west of Alexandria was used by Christians from the 4th until the 6th century (Kraus 2018:54). The other occasion in which Psalm 90 was used was in Kertsch in South Russia on Crimea, dating back to 491 CE (Kraus 2018:47-63).

The entire Psalm 90 was inscribed on the wall of a tomb for protection during the transition to the afterlife, so that the deceased can be safe from all kinds of evil and disaster (Kraus 2018:47-65).

An amulet made of copper alloy, which looks like a kind of amulet with an eyelet, was found in ancient Kibyra in Turkey with an inscription of Psalm 90, to be carried around the neck for a fight against all evil and misfortune (Kraus 2018:47-63). There are also armbands with textual and iconographic elements, meant to turn away and to protect people from all evil powers (Kraus 2018:47-63).

Kraus (2018:47-63) also has in his database five rings with the initial words of Psalm 90, made of silver and other bronze. On these rings are clear inscriptions with clear messages sent to the evil powers 'I am protected by God, at least I strongly believe in Him and invoke that'.

Apart from the above, other archaeological discoveries support the likelihood that ancient Israelites used the Psalms in their memorising, chanting, singing, and inscribing on their clothes, walls, rings, papyri, parchments, doorposts, pendants, tablets, and bodies for protection (Smoak 2011:72-92). Like the African (Yoruba) Christians, the ancient Israelites believed in the Psalter as divine, potent, and performative words that can be used to protect, heal, and bring about success (Adamo 2018:1-13b). Although they do not mention Psalm 90 specifically, a handful of Phoenician and Punic amulets dating from the 1st millennium BCE with the same verbs 'guard' (smr) and 'protect' (nsr) written on their surfaces were discovered (Schmitz 2002:818-822; 2010:421-432; Smoak 2011:75-92). The existence of these two verbs in West Semitic inscriptions and the book of Psalms indicate some common cultural or religious practices (Smoak 2011:75-92). Many 7th and 6th-century gold bands were also discovered in Carthage with the same inscriptions of the above two verbs, 'guard' and 'protect', as part of the protective formula in the Psalms (Barnett & Mendelsson 1987; Krahmalkov 2000:471-472; Smoak 2011:72-92). It is quite unfortunate that these documents have not been publicised and well-studied by many biblical scholars, as is supposed to in many journals and books.

Conclusion

Psalm 90 teaches an act of faith, hope and love, instead of futility. The psalmist's faith and trust put him or her in communion with the past generations who found a dwelling place in God. To the psalmist, sin and death are inevitable realities, but there are love and kindness which bring God's forgiveness and life.

The fact is that '[t]ext travels through history, including our own, … only becomes meaningful as it communicates and generates meaning in particular contexts' (Lacocque 1998:7). In other words, every text is like a picnic to which the author brings the words and the reader the meaning (Hirsch 1967:1).

Readers should thus not be surprised that the Bible, as a sacred object, is very pervasive in African (Yoruba) Christianity. In other words, the same Bible, no doubt, is understood by many ordinary Christians in Africa as an object that contains intrinsic power: a fetish or a talisman (Ukpong 2000:590). A person who cannot read may even place a Bible in his or her purse, or under the pillow for good fortune and safety (LeMarquand 2012:189-199). Of course, the Bible is widely understood in Africa as containing a message about God's love and grace that bring salvation and spiritual support, but it is also considered a weapon to be used in spiritual warfare.

African (Yoruba) Christians create new ways to speak to and understand God through the reciting of the Bible, inscribing texts on parchments, doorposts, vehicles, bodies, and tombs, chanting, singing, and wearing them on the neck and waist (Adamo 2015b:1-13). By doing this, Africans (Yoruba) have taken up the responsibility of voicing and creating new ways to speak to and understand God.

Admittedly, Africentric interpretation of Psalm 90 may be labelled magical. But after all, is Christianity not magical in its manifestation when one examines the Bible or the Word of God and the Christian experiences of many instances of miracles by words, water, laying of hands, and others? What appears to be different is the method of using Psalm 90 to achieve divine protection, healing, and success. When Psalm 90 is read repeatedly, memorised and chanted, inscribed on parchments, worn and put under a pillow, or hung at the four corners of the house, it is the expression of faith in the God of Israel to perform the same miracle of protection, healing, and success which He performed for the people of ancient Israel. It is the belief that God can still perform such miracles by using any instrument, especially when it appears as if there is no hope.

To many Euro-American scholars, Psalm 90 is an eloquent poem on the security of a person who trusts in Yahweh, but to the majority of African (Yoruba) biblical scholars and ordinary African readers, it is more than a poem; it is also an incantation, talisman, and medicine that God has given for divine protection, healing, and success.

As fetish as using Psalm 90 in the African (Yoruba) context may be, it is useful to understand the importance of the practice to African (Yoruba) people. Memorising, chanting, reading, singing, inscribing, and wearing Psalm 90 is a way of bridging the distance gap between the biblical events in the past and the present. It is a way of representing the history of God's event with a strong faith that God will repeat such events in the life of those singing, wearing, and inscribing Psalm 90. Those who use Psalm 90 take on the identity of the worshippers of ancient Israel, concerning the narrative of Psalm 90, which is one of the most important sources of the peculiar power of the Psalms (Nasuti 2001:144). Memorising, chanting, reading, singing, inscribing, and wearing Psalm 90 is a way of receiving the transformative power of God's words in the Psalms. This is the re-experiencing of God's salvation history. This recitation has the power of symbolically participating in an ancient community of faith. It is a way of reaffirming African (Yoruba) faith in Yahweh to protect, heal, and bring success as the original ancient Israelites did in the wilderness.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interests exist.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Adamo, D.T., 2001, Reading and interpreting the Bible in African indigenous churches, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2015a, 'The task and distinctiveness of African biblical hermeneutics', Old Testament Essays 28(1), 31-52. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n1a4 [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2015b, 'Semiotic interpretation of selected Psalms inscriptions on motor vehicles in Nigeria', 7, 1-13, viewed 10 March 2017, from https://scriptura.journals.ac.za. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2018, 'Reading Psalm 23 in African context', Verbum et Ecclesia 39(1), a1783. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v39i1.1783 [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2019, 'Reading Psalm 35 in Africa (Yoruba) perspective', Old Testament Essays 32(3), 936-955. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2019/v32n3a9 [ Links ]

Alter, R., 2007, The book of Psalms, Norton, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Anon., n.d., The uses of psalms, Brothers Bookshop, Onitsha. [ Links ]

Barnett, R.D. & Mendelssohn, C., 1987, Tharros: A catalogue of material in the British museum from Phoenician and other tombs at Tharros, Sardinia, British Museum Publications, London. [ Links ]

Boring, M.E., 2001, 'Psalm 90: Theology as prayers', Mid-Stream 40(1-2), 111-118. [ Links ]

Boring, M.E., 2002, 'Psalm 90-reinterpreting tradition', Mid-Stream 40(2), 119-128. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W., 1984, The message of the Psalms, Augsburg, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. & Bellinger, W., Jr, 2014, Psalms, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Bullmore, M., 2016, 'Numbering and being glad in our days: A meditation on Psalm 90', Themelios 41(2), 289-292. [ Links ]

Clifford, B.J., 2000, 'What does the psalmist ask for in the Psalms 39:5 and 90:12?', Journal of Biblical Literature 119(1), 59-66. https://doi.org/10.2307/3267968 [ Links ]

Clifford, R., 2003, Psalm 73-150, Abingdon, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Creach, J.F., 1998, 'The shape of book four of the Psalter and the shape of second Isaiah', Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 23(80), 66-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908929802308004 [ Links ]

Dopamu, A., 1982, 'Gynaecology among the Yoruba', Orita 14(1), 37-42. [ Links ]

Dopamu, A., 2000, Ma mari kan: Ofo isegun, Sefer Books, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Hirsch, E.D., 1967, Validity in interpretation, ANET265-266, Yale University Press, London. [ Links ]

Holter, K., 2014, 'Pregnancy and psalms: Aspects of the healing ministry of a Nigerian prophet', Old Testament Essays 27(2), 428-443. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F. & Zenger, E., 2005, Psalm 2, Psalm 51-100, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Jens, W., 1995, 'Psalm 90, on transience', trans. W. Linss, Lutheran Quarterly 9(2), 177-189. [ Links ]

Krahmalkov, C.R., 2000, Phoenician-Punic dictionary, pp. 471-472, Peetrers, Leuven. [ Links ]

Kraus, T., 2018, 'Greek Psalm 90 (Hebrew Psalm 91) - the most widely attested text of the Bible', Biblische Notizen 176, 47-63. [ Links ]

Lacocque, A., 1998, Thinking biblically: Exegetical and hermeneutical studies, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

McCann Jr, C., 1993, A theological introduction to the book of Psalms, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Mepaiyeda, S.M., 2013, 'The emergence of African indigenous churches and their contribution to the growth of Christianity in Africa', in S.A. Fatokun (ed.), Christianity and African society, pp. 32-42, Bookright Publishers, mixedIbadan. [ Links ]

Mournet, K., 2011, 'Moses and the Psalms: The significance of Psalms 90 and 106 within Book IV of the Masoretic Psalter', Conversations with the Biblical World l(31), 66-79. [ Links ]

Nasuti, N.P., 2001, 'Historical narrative and identity in the Psalms', Horizon in Biblical Theology 23(2), 132-153. https://doi.org/10.1163/187122001X00071 [ Links ]

Nwokoro, E.O., 1994, The mystic power of the psalms: On selected chapters for daily use, MAP, Calabar. [ Links ]

Ogunfuye, J., n.d., The secret of the uses of Psalms, Ogunfuye Publications, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Olatunji, O., 1984, Features of Yoruba oral poetry, University Press, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Schmitz, P.C., 2002, 'Reconsidering Phoenician inscribed amulet from the vicinity of Tyre', Journal of the American Oriental Society 122, 817-822. https://doi.org/10.2307/3217621 [ Links ]

Smoak, J.D., 2010, 'Amuletic inscriptions and the background of YHWH as guardian and protector in Psalm 12', Vetus Testamentum 60(3), 421-432. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853310X504856 [ Links ]

Tanner, B.L., 2014, 'Book four of the Psalter: Psalm 90-106', in N. deClaisse-Walford, R.A. Jacobson, B. LaNeel Tanner (eds.), The book of Psalms, pp. 685-696, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Tarnner, A., 2007, Effective uses of Psalms, Great Hound Books, Lagos. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J., 2000, 'Popular readings of the Bible in Africa and implications for academic readings', in G. West & M. Dube (eds.), The Bible in Africa: Transactions, trajectories and trends, p. 590, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Urbrock, W., 1998, 'Psalm 90: Moses, mortality, and the morning', Currents in Theology and Mission 25(1), 26-29. [ Links ]

Wilkinson, J., 1998, The Bible and healing, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Wilson, G., 1986, 'The use of royal Psalms at the seams of the Hebrew Psalter', Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 11(35), 87-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908928601103505 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

David Adamo

adamodt@yahoo.com

Received: 17 July 2019

Accepted: 07 May 2020

Published: 22 Sept. 2020

1 . The Greek and Hebrew equivalence of Psalm 90 is attested on a magical bowl and a fragment from the Genizah in Cairo. It appears in the Talmud, the Targumim, the Midrashim, and the Sefer Shimmush Tehilim (Kraus 2018:49). For further information, Kraus has a database of documents where Psalm 90 was attested. A part of Psalm 90 was also used in the New Testament in Luke 4:10-11 and Matthew 4:6 and 8.

2 . The New English Bible of 1961 was an exception.

3 . Creach (1998:66) argues convincingly that there is a strong literary relationship between Book IV and Second Isaiah (vv. 40-55) because (1) both believe that God is a king; (2) both begin by contrasting the faithfulness of God and the ephemeral nature of humanity; (3) both emphasise God's ultimate covenant loyalty and compassion; (4) both have the term נחם at the beginning and the end.

4 . The pair numbers, 'seventy' and 'eighty' in verse 10 are parallel numbers like that of 'three' and 'four' in Amos 1-2, and six and seven in the book of Job 5:19 and Proverbs 6:16-19. It is a statement about Ancient Israel enduring a period of divine absence (Clifford 2003:99).

5 . A similar prayer occurs in the story of Moses in Exodus 32:12: 'Turn (שׁוב) from your fierce wrath; change your mind (הנחם) and do not bring disaster on your people' (Mournet 2011:71). It is at this time that Moses pleaded with God to relent of his judgement about to be meted against the Hebrews. What is interesting, is that both terms occur in the same form in both passages, that is, שׁוב in Qal imperative masculine singular; in the הנחם niphal imperative masculine singular (Mournet 2011:71).

6 . Adamo (2019:943-948).

7 . The Supreme Being.

8 . Christianity came to the Yoruba people in about the 16th century.

9 . The Exodus story and the wilderness journey in the Old Testament are stories of protection (Ex 14). Exodus 15:16-24 says the Lord is the healer and he healed directly (Gn 18:11-14). Healing took place by the prophets (1 Ki 17:21; 2 Ki 2:19-22; 5:1-14). The New Testament is also full of miraculous healing (Mt 9:27-31; Mk 7:31-37; Lk 13:11-17; Jn 9:1-41). The story of success took place in the Old and New Testaments. The possession of the land of Canaan promised to Abraham is a story of success and so is the multiplication of the 5 000 fishes (Mt 14:17-19) (Wilkinson 1998:64-76).

10 . There are other reasons for separating from the mainline missionary churches.

11 . The use of the Bible as a protection against enemies, witches, and wizards is a common thing in African indigenous churches in Nigeria (Adamo 2001:67-81). This practice has also spread to other African countries on the African continent and Euro-American countries, especially among the African Diaspora.

12 . This is a chemical compound of potassium that is used to improve soil for farming and making soap.

13 . Ifa is a Yoruba divination that reveals secrets.

14 . Orunmila is another Yoruba divination and is the divinity of destiny and prophecy.

15 . Ofo is to be recited with the plant not to be chewed.