Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.41 no.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2041

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Positioning care as 'being with the other' within a cross-cultural context: Opportunities and challenges of pastoral care provision amongst people from diverse cultures

Vhumani Magezi

Unit for Reformational Theology and the Development of the South African Society (URT), Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Pastoral care is an intervention that relies on good and quality relationships between the caregiver and the cared individual, if effective and positive outcomes are to be realised. With increased intermixing of people due to migration, globalisation and other technological advances, caregivers find themselves in complex and awkward situations when attempting to 'care for other' persons from different cultural contexts. This challenge presents opportunities for developing and strengthening innovative care. On the other hand, the challenge poses a threat of worsening the situation or failure to positively alter it. Within this context, the critical humane factor of "being with the other person", enshrined in African humane thinking, as indicated by the notion of Ubuntu, provides a lens of "doing" care across cultures. Care, humaneness and being with the other people are notions that bind humanity universally and yet their expression differs across cultures. This article proposes a framework for positioning pastoral caregiving within a global context as well as suggests guidelines on how global pastoral care utilising the notion of 'being with the other' in global context can be done.

Intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: The article explores the notion of pastoral care from the perspective of care within the global context of pastoral ministry. It draws from the African concept of Ubuntu to develop a care approach that is humane and relational in an effort to foster relevant care across different contexts. The study has direct implications for practical theology particularly pastoral care within cross cultural missions and anthropology.

Keywords: pastoral care; pastoral care and Ubuntu; pastoral care in cross-cultural context; pastoral care in diverse cultures; Ubuntu care; pastoral care in a global context; pastoral care as being with the other.

Introduction and premise: Conceptual framework of pastoral care

The notion of care can be likened to a quality that Google company considers critical in its employees. Finn (2011) commented that Google looks for employees who possess a quality that they call 'googliness'. Googliness is a 'mashup of passion and drive that's too hard to define but easy to spot' (Finn 2011:1). It includes a desire to use technology to make the world a better place. The notion of care, like googliness, is a mashup concept that is hard to concisely define but easy to spot. A caring person is easy to spot. Care has an undisputed affective quality. When care is given, it is felt and experienced. Care can be summed up by words such as 'concern', 'listening', 'empathy', 'kind', 'loving', 'tending', 'attention', 'interest' and many others. However, pastoral care giving is not any kind of care. The care is prefixed by the word 'pastoral'; hence, it has to be understood as such. The ontology of pastoral care as a specific kind of care giving slightly differs from other care approaches, despite having similarities. I refer to ontology in a philosophical sense where it refers to 'nature and structure of reality' (Guarino, Oberle & Staab 2009:1).

Pastoral care refers to the care provided from a spiritual perspective and it is sometimes referred to as spiritual care (Lartey 1997; Louw 2014; Magezi 2016; McClure 2012; Mills 1990). However, within an international context where people approach pastoral care from different religious perspectives, it is important to have clarity on the meaning of 'spirituality'. The role of spirituality in the care and healing of people is globally acknowledged. Puchalski et al. (2014:643) observe that 'international activities and interest have increased over recent years with some nations and regions making efforts to define the role of spirituality in practice and policy'. They further explained that (Puchalski et al. 2014):

Spirituality is the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant, and/or the sacred. (p. 643)

This description of spirituality emphasises (1) a sense of feeling and experiencing purpose and transcendence. It also indicates that (2) human beings have to actively explore (seek and express) purpose and transcendence. Spirituality is a way of (3) connecting with other people, self, nature and the sacred. The definition seems to suggest that spirituality is a medium of connection whereby the connection is both experiential and exploratory. However, how should spirituality be understood for within pastoral care context?

Firstly, spirituality has to do with a relationship with transcendence. Puchalski and Ferrell (2010:1-21) argued that 'spirituality can be understood as one's relationship to a transcendence that for some people might be God and for others might be different concepts of how they see themselves'. The term 'spirituality' is often used synonymously with 'religion' and has a binding and stabilising impact on people's attitude towards illness and suffering. Secondly, 'spirituality represents both the divine perspective as well as the human spirit' (Louw 2014:66). Therefore, I suggest that clarity on what we mean by the divine or transcendence is needed for a meaningful and productive care exercise. Clarity on what we mean by the divine helps us to frame our understanding of spirituality in order to guard against reducing spirituality to a 'psychological construct through psychologisation of spirituality' (Louw 2014:62).

If spirituality is that which gives meaning and purpose to life (Puchalski & Ferrell 2010:4), it is understandable, therefore, why Louw (2014:66) argued that the rediscovery of the value of spirituality within therapy and counselling helped pastoral care to get rid of the domination of psychotherapy. Spirituality helps us to connect life and faith, a kind of reality living where our belief system impacts our lives practically. Spirituality in pastoral care dispels the humanistic approach to care by framing it in a religious context, which, in my case, is a church context. Nauer (2010:55-57) advised that rendering pastoral care (cura animarum) as spiritual care, as done within the field of helping and healing professions, robs pastoral care of its unique identity and connection with cura animarum. Therefore, Louw (2014:61) rightly warned that to merely refer to spiritual healing within the processes of professionalisation is to run the danger of making the ministry of pastoral care superfluous. To avoid this superfluous approach, Louw (2014:61-63) maintained that pastoral care should stick to the notion of 'soul care'. The combination between 'soul' (Hebrew nēphēsh; Septuagint: psuchē; Latin: anima), care and cure captures the core identity of caregiving and can be rendered as the basic proposition for a Christian approach to caregiving, which keeps Christian identity clear (Nauer 2010:66-69).

Soul care, within the Christian tradition, is called pastoral care and is linked to the notion of shepherding (Hiltner 1958). The term 'pastoral' is derived from the Latin term pascere (Waruta & Kinoti 2000:5), which means 'to feed'. In view of this Latin root, the adjective 'pastoral' suggests the art and skill of feeding or caring for the wellness of others, especially those who need help most (Waruta & Kinoti 2000:6). So, when one considers pastoral care, the notion of skilful feeding or helping is critical. The feeding is not done anyhow, but from a particular perspective of spirituality. And yet it is important to have clarity on the meaning of spirituality. Pastoral care and spirituality within Christian thinking are linked to the dynamics between a messianic spirit that is resident in people and the mysterious healing and hope in the presence of God. Pastoral care should be informed by the eschatological perspective of Christians. The eschatological perspective defines who we are as Christians. It entails a transformed disposition and attitude to life, ethos and fellow human beings, amongst others. The eschatological dimension redefines who we are. It describes a new state of mind, a new state of being.

If pastoral care is spiritual care provided from a particular perspective, which, in our discussion, is Christian spirituality and how do we position pastoral care within the global space? Pastoral care within global discourses stretches the notion of pastoral care to international politics, international relations and ethics of multinationals. The question is, 'what is care in these spaces?' Louw (2014:85-86) considers pastoral care as focusing on hope within a global context. He argues that hope and healing within pastoral care have become human existential issues. According to Louw (2014), pastoral care is:

[C]losely related to issues such as human rights and human dignity. Hope thus within the framework of global human issues should be transformed from a pietistic stigma into a networking activity that advocates for human rights and human dignity. But human rights and human dignity deprived from the realm of spirituality can become merely a pragmatic mode of activism without the sustainable horizon of normative values and constructive framework of belief systems, philosophies of life that prolong a sense of meaning and purposefulness. (pp. 85-86)

The spiritual dimension in pastoral care is not focused on the individualisation of a private soul, but on networking dynamics that take the formation of social identities into consideration. Pastoral care takes relationships seriously. Effective pastoral care should include a strong and effective networking and effective relationships to ensure meaningful caregiving. Then what are the challenges that pastoral care should engage with in the current global context?

The dynamics of global pastoral context

If pastoral care, as spiritual care, is not only focused on the private or individual soul but also on human beings as relational beings, the question we may need to pose for our discussion is as follows: how can pastoral care be meaningfully performed in a global space? In other words, how can pastoral care be performed in situations where people from different contexts interact, co-exist and interface with each other? Many pastoral care scholars have wrestled with this question and offered some insightful perspectives. For instance, Augsburger (1986), in his book Pastoral Counseling across Cultures, discusses the dynamics of pastoral care and counselling across cultural lines and argues for cultural sensitivity as an approach to an inclusive understanding of pastoral care. Louw (2014) in Wholeness and Hope Care maintains that interculturality is a creative response to diversity in a global context. Fukuyama and Sevig (2004), in their essay Cultural Diversity in Pastoral Care, argue for the notion of multicultural engagement. Lartey's (2002) essay, entitled Pastoral Counselling in Multi-Cultural Contexts, explores ways in which pastoral counselling reflects cultural preferences by referring to Western, Asian and African contexts to show how culture affects the practices of counselling and suggests the need for respect for the universal, cultural and unique aspects of all persons. Lartey (2002) argues that these three aspects (universality, culture and the uniqueness of all persons) should be held together in creative dynamic tension. However, before offering a perspective on care in a global context, we need to be aware of the context and dilemmas being faced on this space. I will describe this dilemma by providing a synoptic glimpse of the current prevailing global issues.

As much as the global context is awash with opportunities, the challenges are equally enormous. There is a rise in new behaviours that we cannot control, suppress or guide with considerable confidence. For instance, a youth in a rural African village interacts with an American superstar on YouTube. The rise of the Internet and the new generation of millennials present new challenges, as boundaries are being pushed, ideas are challenged and traditions are being questioned. New attitudes and behaviours that do not respect our heritages, traditions and foundations are on the rise. In recent years, there is increased mobility and migration in the world (International Organization for Migration 2015:1). People easily move from one country to another (migration) because of easy transportation. Technology and the Internet of Things make information, knowledge and certain accesses easy. The so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), with its entanglement of artificial intelligence (AI), robots and disruption, including the rising threat of misinformation (fake news), is sending global shock waves (Petrillo et al. 2018). People are becoming uncertain and anxious about things. People are constantly googling your theories, statements, diagnosis and advice.

There is growing suspicion, distrust and uncertainty alongside the obvious privileges and opportunities arising in the global world. We are experiencing contradictions and confusion as we seem to be moving forwards, backwards, sideways and upwards, resulting in a feeling of being caught up in a cul-de-sac. We have been experiencing trade war between the USA and China, tension between Japan and Korea, England and the European Union in Brexit, renewed USA and Iraq and Iran tensions, England and Iran and Iraq, and many other developments. On the economic front, we are increasingly experiencing cynicism on global capitalism and the threat of implosion because of corporate greed. Examples include the recent financial crisis and collapse of big firms like Enron in the USA, profit falsification by companies like Steinhoff (McKune & Thompson 2018) and Tongaat Hulett (De Villiers 2019) in South Africa, collusion and direction of public resources to feed a few greedy individuals through corruption and the so-called state capture in South Africa, the exposure and shaming of self-governing global federations like Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) in the awarding of World Cup hosting rights to Russia in 2018 and Qatar in 2022 (Sports 24 2019) and many other issues. The world has also witnessed the abuse of goodwill and hospitality in certain countries, where migrants and refugees who have been given refuge turn out to be terrorists (Simcox 2018). Religion is rising in influence, despite the prediction that it will be consumed by secularism and rendered irrelevant (Beyers 2014).

The above developments cause disorientation and confusion. People meet and co-exist with different emotional, social and physical concerns that sometimes make relating meaningfully difficult. Louw (2014:86) advises that the foundation of pastoral care (cura animarum) is hospitality. Pastoral care, as soul care, is connected to the foundational principle of caritas and diakonia, which indicates hospitality. Caritas and diakonia refer to the networking system of care. Care for 'the other human being' in the global state of flux and confusion calls for solidarity with other human beings. It calls upon caregivers to develop competencies that enable them to function contextually in a global context (Weiss 2002:13). In order to care for other human beings in such a confused situation, one needs to develop competencies and skills in the art of being with other people. This entails mastering the art of relating and connecting. Therefore, I would suggest that the art of being with other people can be summarised and embodied in the notion of Ubuntu.

Ubuntu as a pastoral care principle to foster qualities of 'being with the other' human beings

Ubuntu is 'a distinctive African quality that values collective good, humanness and respect for the community' (Magezi 2017:112). It is a foundational ethic of meaningful communal relations in many African communities. Ubuntu is difficult to concisely define. Tutu (2009) explained the difficulty in defining Ubuntu as follows:

Ubuntu is very difficult to render into a Western language. It speaks to the very essence of being human. When we want to give high praise to someone we say, 'Yu, u nobuntu'; 'Hey, he or she has ubuntu'. This means they are generous, hospitable, friendly, caring, and compassionate. They share what they have. (p. 34)

Many African scholars (Chisale 2018:4; Gathogo 2007:112; Letseka 2013:355; Manyonganise 2015:1; Van Norren 2014:256) maintain that Ubuntu summarises the notion that 'I am because of other people' (Mbiti 1990:106). In this regard, Ubuntu means communality, commonality, mutuality and interdependence. Our existence as human beings is bound in contextual realities with other people. Our spirituality is lived, expressed and experienced within a community. African spirituality is linked to a strong communal existence and community participation in care. Caregiving is performed by the community to the community, by the community to the individual and by the individual to the community.

However, Ubuntu can easily degenerate into an unhealthy stuckness. Magezi (2017:117) observed that in the traditional Ubuntu framework, an individual feels bound and obligated to respond to the needs of people related to him or her. One is also inclined to assist people who come from the same geographical area. This is evident in political and employment circles. When a new president is elected there is generally a tendency to appoint someone from the same geographical area. Similarly, it is not uncommon that when someone is appointed to a senior government position, he or she recruits family and community members. While this is viewed as nepotism, to the community, the appointed person is truly practising Ubuntu. Thus, traditional Ubuntu in its current practice is exclusive to 'your people'. Benevolence and acts of good and bad are determined by the family and community. The Nigerian philosopher Turaki commented in his unpublished lecture delivered at North-West University that working in government or public office is like hunting. You kill a gazelle and share it with your relatives and community. This practice dates back to wars between villages where the warrior defeats another village and plunders their livestock. His entire village welcomes him as a hero. Therefore, some government officials take plunder back to their villages. These people would be viewed as practising true Ubuntu, where Ubuntu is narrowly limited to friends, relatives and the close geographical community. No one accuses the individual of corruption, but rather praises him or her for thinking of his or her people back home in the village.

To overcome the unhealthy stuckness of Ubuntu, Magezi (2017:118) argues that Ubuntu should be revolutionised or moderated by Christian values. True Ubuntu should be informed and influenced by a transcendent dimension, a sense of divine ethos and values, rather than benevolence judged by peers and family members who share in one's situation, whether corrupt or inhumane. True Ubuntu values are Christian values where human beings are universally bonded by Christ and the sense of humanity. Thus, when the humanistic notion of human dignity, based on human rights (dignitas), and the theological notion of the image of God (Imago Dei) are considered together, pastoral care will be for the service of the community by community individuals. In the image of other human beings, we see God, a reflection of the divine creative art that is worth embracing. Fellow human beings will reflect the beauty (aesthetics) of God in creation (Cilliers 2012:58-64).

Therefore, in order to care for other human beings, one needs to understand, appreciate and acknowledge other human beings. This entails recognising the beauty of humanity in other human beings. The Christian notion of oneness regards humanity as brothers, sisters and family; thus, koinonia becomes crucial in this regard. Oneness in diversity entails reflecting on a rainbow nation like South Africa and seeing the beauty of being one, but being many at the same time. Christianity and our being challenge us to strive and imagine how this can be achieved (imagination). Acknowledging the other is about seeing the unseen, the beauty behind someone who is different from me, a gem behind colour, and seeing yourself as a mirror of the other human being. This entails recognising that I reflect the other human being even though we are different. As Louw (2014) rightly maintains, the notions of caritas and diakonia indicate the dimension of reaching to others. However, reaching out to other human beings requires some kind of theological seeing. This seeing is beyond the physical human mind and eyes, but it is spiritual seeing, which is a vision of the heart. Smit (2003:55-70) urges people to learn to see. The heart represents open embracing arms - embracing the other who is different from me. Hence, our pastoral care is challenged to cultivate a vision of seeking faith within the space of real-life spaces. Our seeing is a function of our ontic being as eschatological beings. Pastoral care, therefore, cannot be separated from our disposition as Christians. Being in Christ defines our views of other people and challenges us to treat them with dignity and explore sacrificial ways to serve others.

Thus, the notion of Ubuntu and the associated concepts of relationships, community participation, cooperation, solidarity, humaneness and connectedness get reframed and reoriented by Christian spirituality. 'Being with other people' and caregiving get altered to focus on fellow human beings universally. Pastoral care, thus, stretches care to global discourses of international politics, international relations and ethics of multinationals. Therefore, pastoral care cannot afford to be neutral on spiritual identity. Louw (2014) advises that:

The framework of global human issues should be transformed from a pietistic stigma into a networking activity that advocates for human rights and human dignity. But human rights and human dignity deprived from the realm of spirituality can become merely a pragmatic mode of activism without the sustainable horizon of normative values and constructive framework of belief systems, philosophies of life that prolong a sense of meaning and purposefulness. (pp. 85-86)

The question is then 'what is care in these spaces?', and 'how could pastoral care be conceived and performed in global spaces where moderated Ubuntu principles could be applied for effective pastoral caregiving?'.

Towards a framework for positioning caregiving within a global context

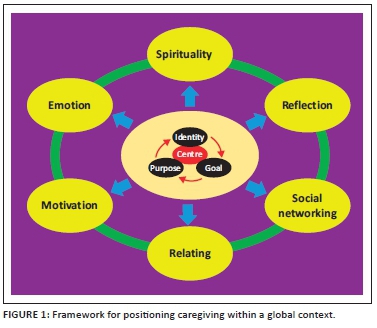

The framework presents pastoral care as two concentric circles with embedded elements. Each element interacts with the other elements to inform and influence meaningful caregiving (see Figure 1).

The driving centre of pastoral caregiving

The inner circle of the model represents what I could metaphorically call the 'heart', 'nucleus' or 'engine' that drives caregiving. In business strategy or organisational thinking, it can be likened to a vision, mission and value statements that form the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of the organisation. It outlines the organisation's identity, purpose of its existence, mission and intentions.

The first element of pastoral caregiving that forms the heart of our caregiving is identity. At stake is the following question: who are we as caregivers? Our identity is intricately linked to the ontology of who we are as caregivers. Our assumptions, motives, intentions and goals are influenced by and flow out of our identity. This challenges us to be clear about who we are as pastoral giving enterprises. Our ontology (i.e. our being) as pastoral caregivers, particularly from a Christian caregiving perspective (which is my perspective), relates to our new state of being - our eschatological state as spiritually transformed people. Our transformation provides new perspectives on our ethos, values and views of humanity, amongst other things. Our identity as new beings has diakonic implications for fellow human beings. Our vocation as human beings becomes intertwined with our expectations for service. Our lives get inevitably entangled with other people. We get gripped by a sense of deontological ethics, which is our duty to humanity - our fellow human beings. Thus, our ontic condition has implications for the way we think, the way we relate, our motivations, our emotions and our human networking processes. Our identity becomes an embodiment of the divine that indwells us. We become a bundle of hope emitter.

We cannot afford to embark on a caregiving task without clarity about who we are. In research, this relates to your own position and how you are entering the research process. To lack clarity is to be guilty of being unethical, as you will be unconscious of your own position, prejudices and stereotypes because of your default automatic position. Being aware and laying it bare that pastoral care by a Christian will be informed by Christian presuppositions is critical.

The second element of the nucleus of pastoral caregiving is our goal. Our goal should be linked to our quest for human wholeness, which is located within a spiritual perspective. Spirituality links our practical wholeness to a transcendent dimension. These two aspects - practical life and the mystical - which are divine (transcendence) dimensions, integrate our existential realities and the divine healing dimension to foster meaning and coping in life. As a result, our faith becomes a life science (Louw 2014). I argue that while our goal is practical mitigation of problems, there should be a link to a futuristic hope dimension as a result of our eschatological hope. Therefore, pastoral caregiving should be explicit in its intention and goal of spiritual transformation as a crucial component of healing in caregiving.

The third element of the nucleus of pastoral care is the purpose of caregiving. Our purpose relates to our vocation. While identity refers to our ontic being and goal, it relates to our intended achievements and purposes as well as defines our task (vocation). The task arises from that which we are expected to perform because of who we are (identity) in order to achieve our goal. A caregiver is challenged to operate in a manner that advances the goals of caregiving. Therefore, identity, goal and purpose form the nucleus (the heart or energising source) that influences our caregiving processes.

Dimensions interlinked with the heart of pastoral caregiving

Emerging from the inner circle that indicates the heart of pastoral caregiving, the second circle shows six dimensions. These are spirituality, reflection, motivation, social networking, relating and emotions. These dimensions interact with each other to influence meaningful caregiving. For instance, spirituality gives a perspective that informs reflection (thinking), how we relate, socialise and network as well as how we feel. Miller and Jackson (1995:76) clearly describe the interrelationship and interactions of some of these dimensions. They rightly argue that during pastoral assessment for intervention, one has to understand that cognition (thinking), affective (feelings and emotions) and behaviour (actions) dimensions are intricately linked. That is, cognition (thinking), affective (feelings and emotions) and behaviour (actions) are not as separate as they can be made to be when human beings are dichotomised. They all interact to provide a wholesome human being in caregiving.

The first dimension is spirituality. Our appreciation of other human beings is linked with our ontic being as spiritual human beings providing spiritual care. Our connection and relationship with the divine have implications for our interactions with fellow human beings. Our being as spiritual carers should make us think, relate, network, feel and motivate to genuinely care for other people out of sincere love. Our spirituality should awaken within us a sense of duty towards and responsibility for other human beings. Therefore, it is imperative to have clarity on the meaning of spirituality. Our understanding of spirituality should propel us towards positive actions of compassion and diakonia. Our sense of purpose, meaning, destiny and vocation is awakened and intricately connected to the energy derived from our spirituality. The framework spells out the need to maintain or keep a sense of our spiritual caregiving call. The spiritual dimension of care - namely, the paracletic dimension of comfort and the solicitous dimension of empathetic shepherding and its connection with the eschatological realm of the spiritual healing of the human 'soul' - provides pastoral caregiving a unique dimension. Louw (2014) warns that:

It seems that without the emphasis on the spiritual dimension of life, faith and the religious realm of transcendence, suffering and the challenge of meaning-giving, the inevitable reality of tragedy, the existential realm of transience, the human predicament of helplessness and the quest for hope, the tradition of cura animarum is in the danger of deserting its unique features and starts to embark on avenues that have already been occupied by the other helping professions. The real danger lurks that caregivers could become merely quasi-psychologists or artificial sociologists. (p. 55)

The second dimension is reflection, which entails the manner in which we think or view other human beings. If one views other human beings as inferior, subhuman or not equal, it results in mistreatment and feeling of not deserving of care and concern. Many atrocities in the past and nowadays arise from the way we think of other people. For instance, slave trade was driven by a view that other people were subhuman; the Christian crusades in the Holy Land were motivated by a sense of superior religion, racism, classism and nepotism. Many other discriminatory practices are fed by a sense of superior view of self and an inferior sense of the other. On the one hand, if one thinks or views the other person as important, or as a valuable and equal person deserving of care, it would influence us to be empathetic and view people positively. We will desire that the peace and comfort that we enjoy are also enjoyed by the other person. On the other hand, if we view others in a negative light, we will exude a negative attitude and disposition towards them. We will develop a sense that they do not deserve our care and sympathy. Is it not perplexing that the most sophisticated war weapons are made to kill other human beings? This baffles the mind. In South Africa, this kind of thinking that regards people who are different as inferior has fuelled xenophobia. People have been burnt to death or butchered with knives. The genocide in Rwanda was fuelled by a sense of superiority and inferiority. The rhetoric of anti-other religions, anti-other people groups, anti-certain countries, anti-certain races, etc., fuels negative perceptions and views of other people. Sadly, the way we think of other people is our defacto mode, an unconscious natural mode of doing things without reflection.

The intention of the framework is to challenge us to be intentional and act consciously. We need to intentionally reflect on things that concern our fellow human beings. Reflection is a cognitive process. It challenges us to reflect on our perceptions, stereotypes, prejudices and who we are in light of other human beings. Reflection is a challenge to cultivate curiosity and knowledge about other human beings. It is about research and inquisitiveness to see the beauty in others' behaviour and culture. This corrects misconceptions and dispels simplistic popular thinking on which many people base their assumptions. Our identity as spiritual caregivers challenges us to think, value and respect other human beings as beautiful creation. The South African practical theologians Louw (2014) and Cilliers (2012:60) rightly suggest the need to imagine and appreciate the beauty (aesthetics) in other human beings created by God as a practical ministry duty.

The third dimension is motivation. Motivation relates to the telos or goals of our human encounters. I argue that pastoral care should have an integrating principle, a bond that binds and informs our approach within our religious traditions. For instance, as a Christian, I maintain that the bond of our Christian spirituality is Christ. What do I mean by that? I mean that Christ is the bond that binds us as brothers and sisters belonging to one family of God and humanhood. The notion of oneness as brothers and sisters places a challenge on us to consider the needs of others. Our motivation to care for others includes the desire to nurture and mature people in God in order for them to cope. This entails embodying and enfleshing God to the entire world, bringing hope and making people experience hope and meaning through us, as a medium of hope. This does not imply an imposition of one's beliefs on people, but rather being a channel of hope. The underlying driving factor of Christ's love that binds us is a crucial motivation factor. Therefore, I argue that clarity is required regarding that which motivates us to engage in the care of other people. Is it just a job as a Chaplain or there is much more to it? I maintain that without clear motives, our care will lack a clear goal, objective and substance. Pastoral caregiving becomes diluted and weak psychology that is neither useful nor relevant in social sciences, and also not fit for purpose as faith care. This may mean empathy becomes our goal, hence diminishing the critical stance of spirituality. Spirituality defines our ontic condition through which we strive to mediate God's care to other human beings in order that they may experience God's caring love, despite their suffering and pain.

The fourth dimension is social networking, which is our ability to use our interaction skills to effectively connect with other human beings. Social networking entails effectively developing and deploying our people skills, such as listening, sensitivity, empathy, humaneness, genuineness, warmth and embrace, and negotiation to ensure meaningful caregiving. Within the situation of the rising 4IR that is powered by technological advances, information access, robotics and AI, there is already a talk inversion of exchange of status between hard (technical) skills and soft skills (social and human networking skills). As technological skills are increasingly taken over by computers and robots, for example, psychometric or psychospiritual assessments, the obvious things that AI, computers and robots will not be able to replace is our innate abilities to relate, connect, interact and be human beings. Therefore, social networking grapples with the following questions: 'what is the nature of my social networks?' and 'how do my social networks support and advance the needs and desires of other human beings?' Indeed, social relating and networking become crucial differentiators of what it means to be human, including to support human beings, and to be empathetic and connect to other human beings. Therefore, the framework raises consciousness on the need of cultivating social networking competencies.

The fifth dimension of the framework is relating. Relating is a social dimension that entails interaction, intelligence and sensitivity. It is an art that has to be learnt and practised at all times. It includes unlearning old ways of interaction and relating and learning new skills for effective functioning. The learning entails developing and mastering of skills to function in new environments in cross-cultural contexts, such as learning the collective ethos of a people in a new country. For instance, an African person may feel isolated when he or she visits a Scandinavian country like Norway, where people, with their earphones on, tend to be very quiet and distant. Conversely, a Scandinavian visitor to an African country may feel pressured and not given space, while the African host is being naturally hospitable. Therefore, relating cannot be learnt like a mathematical formula, but as an art where principles are internalised and actions are practised in the real spaces of life. The framework alerts us to the challenge of relating and raises consciousness on the need of developing relating skills.

The sixth dimension is emotions. The emotional dimension entails our feelings about other people who are different from us. It includes coming to terms with our own prejudices and the emotions, which are triggered within us as we attempt to stretch out to reach other people. It relates to the tension between reaching out to the other person and remaining in our comfort zones. The emotional feelings arise from the destabilisation of our homeostatic state of existence, a status quo that we cherish. The framework helps us to be aware of our own positions and preferences that hinder service and outreach in life.

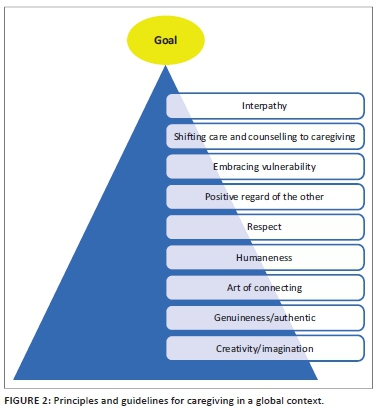

Towards principles and guidelines for caregiving in a global context

The framework for positioning care within a global context revealed the manner in which we should approach pastoral care. However, we have to be conscious of the challenges that we encounter in our pastoral care efforts. The question is, 'what principles can guide us in the process of caregiving in a global context?' To answer this question, I would like to suggest nine principles that could assist us in our task of caregiving in a global context (see Figure 2):

· The first principle is interpathy. Augsburger (1986:29-30) described interpathetic caring as a process of 'feeling with' and 'thinking with' other people from different contexts. This entails an attempt to enter into other persons' world of assumptions, beliefs and values and temporarily take them as one's own. Louw (2014:178) connected two additional concepts to interpathy, namely, 'transspection' and 'interspection'. Transspection refers to an effort to put oneself into the head (not shoes) of another person. Louw (2014:178) explains that interspection is the awareness of the interrelatedness and interconnectedness of meaning within the network of relationships - more or less what is meant by Ubuntu philosophy: I am a human being through another human being. The perspective of the other is important for processes of healing. The question is then 'how does the other perceive and experience me?'

· The second principle entails shifting the mindset from the notion of counselling to caregiving. The African notion of care is about reaching out to the other. An individual's Ubuntu is judged by the strength of the vector towards other people. Similar to this African notion of Ubuntu, caregiving is about going to people, that is, going to places where sick people are (e.g. homes, hospitals and schools). This unfortunately entails a risk of the caregiver being perceived as an intruder, especially within the context of human rights which stipulate that one should only visit the sick when invited. Because of human rights issues, people are caged in boxes of self-autonomy. There is something like an unconscious cold war zone, a kind of a 'pause game' between the caregiver and the person requiring care. The caregiver is afraid of making mistakes and being offensive, while the individual requiring care is suspicious and unsure about the identity and character of the caregiver as well as his or her accessibility. This results in numbness and freezing of care actions. Because of the advancement of technology and Internet access, people are often on their smartphones, resulting in the creation of a kind of solitary confinement while they are in public and community spaces. People ignore others or get ignored in the public as they concentrate on their smartphones. Pastoral care, therefore, should entail reaching out and going to people. This literally and metaphorically means going out to people to be with them and helping them, that is, giving care. This requires us to develop eyes to see people who are in need and reach out to them.

· The third principle is embracing vulnerability as a key caregiving success factor. Vulnerability is considered one of the top five qualities of managers who are preferred in a global context by leading companies (Glanz 2007). Vulnerability entails exposing oneself to being stupid and failing, and yet in that process the lessons you learn are priceless. In modern growth management and leadership-centred thinking, failure is an opportunity to grow, while in the old paradigm of fixed mindset, it is viewed as a limitation of one's abilities. In reaching out to people who are different from us, we will certainly make mistakes and feel lost. But in our mistakes, our fellow human beings will forgive us. As long as we are sincere and genuine, people will forgive us and appreciate our efforts. We learn from mistakes. We have to focus on action, go out and try to embrace others. However, the guiding principles should be love and genuineness.

· The fourth principle is respect, which relates to positive regard of other human beings. We have to approach other human beings in a respectful way. This entails being conscious that differences and diversity make us to be fully human. While respect helps us to positively regard other human beings, it can also cause a negative numbing experience. Within a global context, respect for other human beings can 'freeze us' from action because we will be unsure and fearing to offend other people who are different from us. Hence, respect and positive regard could easily result in dysfunctionality. To overcome this potential downside of respect, one has to be genuine, sincere and ready to embrace vulnerability. People forgive individuals who make mistakes out of sincere love to help.

· The fifth principle is positive regard for other human beings, and it is linked to respect. It relates to our expectations of other people. If our expectations of other people are low, we tend to treat them with little hope for good in our interactions. Conversely, if we have high expectations and hopes for the person, we develop a hope that is exuded to the person. This is called fulfilled prophecy in psychology. Approaching other people with a positive regard entails accepting them unconditionally and acknowledging God's image in them, which results in positive human interactions.

· The sixth principle is humaneness, which is a quality that makes us human. Within the African context, this principle is summed up by the notion of Ubuntu. It is about solidarity and communion as human beings. To be truly human is to be intricately connected to other human beings. Humaneness is a drive to reach other human beings. It includes approaching, conversing, stepping out to assist and making others feel at home (hospitality). Humaneness describes the quality of our relationships, which includes the manner and attitude of how we relate. However, in the global context, humaneness should not be an unhealthy sticking together, where people only socialise with those who we are familiar to them. Pastoral care is guided by humanness through crossing human boundaries to offer meaningful care across cultures.

· The seventh principle is the art of connecting, a concept that refers to developing skills and mastery in relating to people who are different from us. Connecting with people who are different from us does not occur naturally. People tend to interact with people who are familiar to them. The art of connecting is about making effort to learn and understand other people. It entails learning about other people's cultures in order to engage with them in an informed manner. Pastoral caregiving across cultures demands that we apply practical wisdom and knowledge that is informed by our proper understanding of people's situations.

· The eighth principle is genuineness, that is, there should not be any hidden agenda or intentions of manipulating other people during pastoral encounters. It entails genuine concern for the other, which translates to warmth and unconditional embracing of the other person.

· The ninth principle is creativity, which entails imagining ways of relating to others in a sensitive way. Creativity means having an awareness that each individual is unique and has unique expectations and needs. It is about studying the situation and the individual, resulting in one's trying of new ways of dealing with others' situations. Creativity provides insightful ways of intervening in people's situations.

Conclusion

Being with other people in a global context stretches us. It takes us to uncomfortable places in our human interactions. Respect, having a positive regard for other people, acting humanely, genuinely connecting with and reaching out to other people, in love and compassion, are indeed challenges in a global care context. In performing these acts to people in different contexts, vulnerability is inevitable. We become vulnerable to making mistakes, having oversight, acting ignorantly and offending other people. But in all this, our genuine love, concern and compassion for fellow human beings conceal our mistakes in the eyes of others. Love covers all (1 Cor 13:4-6). Our new identity, defined by our eschatological ontic being, gives us purpose and perspective for all humanity. God blesses us so that we may bless others (Psalm 67). We become all things to all people (1 Cor 9:22). Our love and care for other human beings across the world get energised and are given impetus by our sense of our Christian spirituality. Our relationship with a transcendent being, a divine, Creator, God, directly influences us to give genuine care and be genuinely concerned for other human beings. Mistakes will be made, but when they are weighed in the light of our intentions, our goal of giving hope and meaning to people's lives, they are overshadowed and concealed by the veil of goodwill and unconditional regard and love for our fellow human beings.

Who said relating and giving care to someone different from you is easy? It is certainly not easy. And yet it is a task that all pastoral caregivers are called to perform the moment the tag 'pastoral caregiver' is placed on them. Being with the other in a global world sounds like an oxymoron. An oxymoron is a figure of speech in which apparently contradictory terms appear in conjunction. Opportunities and challenges in caring for humanity stand side by side. Our vulnerability stands side by side with hope and optimism. Indeed, being with the other, care for the other and serving the other in a global context is a gratifying challenge, an opportunity to be fully human to other human beings, despite the challenges that one experiences.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Augsburger, D.W., 1986, Pastoral counseling across cultures, Westminster, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Beyers, J., 2014, 'The church and the secular: The effect of the post-secular on Christianity', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(1), Art. #2605, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2605 [ Links ]

Chisale, S.S., 2018, 'Ubuntu as care: Deconstructing the gendered Ubuntu', Verbum et Ecclesia 39(1), a1790. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v39i1.1790 [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., 2012, Dancing with deity. Re-imagining the beauty of worship, Bible Media, Wellington. [ Links ]

De Villiers, J., 2019, 'Tongaat Hulett scandal: Deloitte replaces senior auditors and launches an internal investigation', Business Insider SA, viewed 03 August 2019, from https://www.businessinsider.co.za/tongaat-hulett-deloitte-replaces-auditing-leadership-team-launches-investigation-2019-6. [ Links ]

Finn, H., 2011, Missions that matter, viewed 03 August 2019, from https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-resources/missions-that-matter/. [ Links ]

Fukuyama, M.A. & Sevig, T.D., 2004, 'Cultural diversity in pastoral care', Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 13(2), 25-42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J080v13n02_02 [ Links ]

Gathogo, J.M., 2007, 'Revisiting African hospitality in post-colonial Africa', Missionalia 35(2), 108-130. [ Links ]

Glanz, J., 2007, 'On vulnerability and transformative leadership: An imperative for leaders of supervision', International Journal of Leadership in Education 10(2), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120601097462 [ Links ]

Guarino, N., Oberle, D. & Staab, S., 2009, 'What is an ontology?', in S. Staab & R. Studer (eds.), Handbook on ontologies, pp. 1-17, Springer-Verlag, New York. [ Links ]

Hiltner, S., 1958, Preface to pastoral theology, Abington Press, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2015, World migration report 2015, viewed 23 May 2019, from http://www.un.org/en/…/migration/…/migrationreport/…/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf. [ Links ]

Lartey, E.Y., 1997, In living colour, Cassell, London. [ Links ]

Lartey, E.Y., 2002, 'Pastoral counseling in multi-cultural contents', American Journal of Pastoral Counseling 5(3/4), 317-329 [ Links ]

Letseka, M., 2013, 'Anchoring ubuntu morality', Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4(3), 351-360. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n3p351 [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 2014, Wholeness in hope care on nurturing the beauty of the human soul in spiritual healing, LIT, Wien. [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2016, 'Reflection on pastoral care in Africa: Towards discerning emerging pragmatic pastoral ministerial responses', In die Skriflig 50(1), a2130. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v50i1.2130 [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2017, 'Ubuntu in flames - Injustice and disillusionment in post-colonial Africa: A practical theology for new "liminal ubuntu" and personhood', in J. Dreyer, Y. Dreyer, E. Foley & M. Nel (eds.), Practicing ubuntu: Practical theological perspectives on injustice, personhood and human dignity, pp. 111-122, LIT Verlag, Zurich. [ Links ]

Manyonganise, M., 2015, 'Oppressive and liberative: A Zimbabwean woman's reflections on ubuntu', Verbum et Ecclesia 36(2), Art. #1438, 1-7 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v36i2.1438 [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S., 1990, African Religions & Philosophy, 2nd edn., Heinemann Educational Botswana, Gaborone. [ Links ]

McClure, B., 2012, 'Pastoral care', in B.J. Miller-McLemore (ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell companion to practical theology, pp. 269-278, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Chichester. [ Links ]

McKune, C. & Thompson, W., 2018, 'Steinhoff's secret history and the dirty world of Markus Jooste', Business Live, viewed 03 August 2019, from https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/features/cover-story/2018-11-01-steinhoffs-secret-history-and-the-dirty-world-of-markus-jooste/. [ Links ]

Miller, W.R. & Jackson, K.A., 1995, Practical psychology for pastors, 2nd edn., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Mills, L.O., 1990, 'Pastoral care - History, traditions, and definitions', in R.J. Hunter (ed.), Dictionary of pastoral care and counselling, pp. 836-842, Abington Press, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1990. African Religions & Philosophy. Second Edition ed. Gaborone: Heinemann Educational Botswana. [ Links ]

Nauer, D., 2010, Seelsorge. Sorge um die Seele, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Petrillo, A., De Felice, F., Cioffi, R. & Zomparelli, F., 2018, Fourth industrial revolution: Current practices, challenges, and opportunities, viewed 03 August 2019, from https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/58010.pdf. [ Links ]

Puchalski, C.M. & Ferrell, B., 2010, Making health care whole. Integrating spirituality into patient care, Templeton Press, West Conshohocken, PA. [ Links ]

Puchalski, C.M., Vitillo, R., Hull, S.K. & Reller, N., 2014, 'Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus', Journal of Palliative Medicine 17(6), 642-656. [ Links ]

Simcox, R., 2018, The Asylum-Terror Nexus: How Europe should respond, pp. 1-12, Backgrounder, no. 3314, viewed 18 June 2018, from https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/BG3314.pdf. [ Links ]

Smit, D.J. 2003, 'On learning to see? A reformed perspective on the church and the poor', in P. Couture & B.J. Miller-McLemore (eds.), Suffering, poverty, and HIV-AIDS: International practical theological perspectives, pp. 55-70, Cardiff Academic Press, Cardiff. [ Links ]

Sports 24, 2019, Platini arrested over awarding SWC 2022 to Qatar, viewed 03 August 2019, from https://www.sport24.co.za/Soccer/International/breaking-platini-arrested-over-awarding-world-cup-2022-to-qatar-20190618. [ Links ]

Tutu, D., 2009, No Future Without Forgiveness, Random House, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Turaki, Y., 2015, 'Colonialism, Slavery and Islam', in Lecture presentation, North-West University, Vaal Triangle. [ Links ]

Van Norren, D.E., 2014, 'The nexus between Ubuntu and Global Public Goods: Its relevance for the post 2015 development agenda', Development Studies Research 1(1), 255-266, https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2014.929974 [ Links ]

Waruta, W. & Kinoti, W. (eds.), 2000, Introduction. Pastoral care in African spirituality, Acton Publishers, Nairobi. [ Links ]

Weiss, H., 2002, 'Die Entdeckung Interkultureller Seelsorge: Entwicklung interkultureller Kompotenz in Seelsorge und Beratung durch internationale Begegnung', in K. Federschmidt (ed.), Interkulturelle Seelsorge, pp. 17-37, Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Vhumani Magezi

vhumani@hotmail.com

Received: 14 Aug. 2019

Accepted: 05 Feb. 2019

Published: 07 Apr. 2020