Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Verbum et Ecclesia

On-line version ISSN 2074-7705

Print version ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.41 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2043

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The characterisation of the Matthean Jesus by the angel of the Lord

Francois P. Viljoen

Department of Church Ministry and Leadership, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article uses a narrative analysis to contribute to the discourse on the characterisation of Jesus in the Matthean Gospel. Much is revealed about characters through their actions and words and how other role players in the text respond to them. Sometimes, the narrator directly tells the reader about a character. The kind of character depends on the traits or personal qualities of that character and how that character behaves during specific incidents. Along with God himself, Jesus forms the principal character in the First Gospel. His teachings and actions are central to the text and the actions of other characters are directed towards him. This article focusses on what the angel of the Lord says in support of Jesus. The presence of the angel of the Lord represents the presence of God, and his message is received as coming from the mouth of God himself. The evangelist utilises the speaking of the angel of the Lord as a narrative strategy to assure Jesus' prominence and authority. This angel shows Jesus to be the main character.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: This article uses a narrative analysis to contribute to the discourse on the characterisation of Jesus in the Matthean Gospel. It engages with the field of narrative criticism focussing on characterisation in biblical texts. This has implications for Hermeneutics. It can also be useful for dogmatic research in Angelology and Christology.

Keywords: characterisation; Matthean Jesus; angel of the Lord; narrative criticism.

Introduction

Angels played a significant role in the Second Temple Jewish1 and early Christian cosmology (Sullivan 2004:1). On the basis of their participation in both the heavenly and earthly realms, angels are particularly valuable figures for Christology (Bendoraitis 2015:1). As heavenly beings, they mediate between heaven and earth, and they can therefore act as a significant character group to communicate who Jesus is.

In Matthew, angels sometimes appear as a single character (the angel of the Lord), and otherwise as a group of angels (character group). Angels appear throughout the Gospel, both as acting characters and as characters referred to in the discourses. However, Matthew tells us very little about the angels. With the appearance of the angels in the narrative,2 Matthew 'shows' the character traits of the angels, rather than 'telling' the reader about them. This article focusses on the ways the words of the angel of the Lord shape Matthew's portrayal of Jesus.3 Because Matthew (similar to the other gospels) forms a portrait of the life and ministry of Jesus, it is useful to examine this portrayal of Jesus as informed by his relationship with angels in the narrative.4 The only time Matthew has an angel, delivering a message, this angel is identified as an angel of the Lord. This article focusses on the message of this angel and how it contributes to the characterisation of Jesus.

Words of the angel of the Lord

The angel of the Lord speaks in four instances, three times at the beginning in the birth and childhood narratives (Mt 1:18-25; 2:13-15; 2:19-23) and once at the end at Jesus' tomb (Mt 28:2-10).

The angel of the Lord

Within the category of divine messengers, the angel of the Lord (ἄγγελος Κυρίου) is unique as it carries the divine name. However, identifying this angel is not easy. He could be one particular angel, an angel from a specific class, or an angel that forms part of the generic class of angels of the Lord (Bendoraitis 2015:24).

In the Old Testament, the angel of the Lord is primarily described as one that delivers messages of guidance and comfort (e.g. Gn 16:7-13; 21:17; 1 Ki 1:19:5-7; 2 Ki 1:2, 15). In some instances, he bears the sword against the enemies of Israel (e.g. 2 Ki 19:35; 2 Chr 32:21). The angel of the Lord is even associated with the Lord himself as responses to his message often include praise and prayer, which implies an encounter with God (e.g. Gn 22:9-16; Ex 3-4; Jdg 2:1-4).

It seems that there was a remarkable strengthening in the belief in angels during the Second Temple period (Dodson 2009:153). Apocalyptic literature exhibits a developed hierarchy of angels. The Testament of Adam 4 and Jubilees 2 describes the different orders of angels and their respective roles, such as the angels of presence, the angels of sanctification and angels over natural phenomena. Angels are often depicted as intermediaries through dreams or visions (e.g. Dn 7:16-18, 8:15-16; Zch 1-6; 2 En 1:3-10, 4 Ezr). The angels often have names. In the Book of Daniel, Michael and Gabriel are mentioned (Dn 8:16; 9:21; 10:13, 21; 12:1); 1 Enoch states the names of four archangels: Michael, Raphael, Gabriel and Phanuel (1 En 40.9; 54:6; 71:8). Although these angels are not specifically called 'angels of the Lord', their roles are unique as they carry the messages of the Lord when representing God's authority and presence.

Although it is not possible to precisely identify the angel of the Lord, it is clear that he has a close association with God as signified by the reference to the Lord in the naming of the angel.

Words in the birth and childhood narratives

Matthew writes a typical ancient biography (βίος) of Jesus.5 Although Luke in his birth narratives pays attention to the birth of John the Baptist too, Matthew fully focusses on Jesus. In doing so, Matthew introduces the angel of the Lord (ἄγγελος Κυρίου) as a witness of Jesus.

Matthew's birth narrative follows the convention of the birth topos of heroic figures in ancient Graeco-Roman literature (Dodson 2009:147-148). After the introductory prescript (proem), an encomium would follow with a discussion of the person's origin, such as his nationality, ancestors and extraordinary occurrences at birth, like special dreams. After such remarks, the circumstances of the birth would follow. In Matthew, the prescript (Mt 1:1) is followed by the subsequent genealogy (Mt 1:2-17). After the genealogy, Matthew describes Jesus' birth (Mt 1:18-25). Similar to the ancient writers, Matthew includes a dream narrative in which the angel of the Lord appears.

Each time the angel of the Lord appears in Matthew's birth and childhood narratives, a similar chain of events occurs: the scene is set, the angel appears in a dream,6 the message is delivered, Joseph responds immediately and the fulfilment of an Old Testament passage is explained (Bendoraitis 2015:36; Brown 1993:108).7

Instructing Joseph to take Mary as his wife and to name Jesus (Mt 1:18-25)

The first appearance of the angel of the Lord is when he comes to Joseph in a dream instructing him not to be afraid to take Mary as his wife (see Figure 1).8 This appearance forms the foundation and pattern of God's presence and message. It is repeated in the two subsequent appearances of the angel of the Lord in the infancy narrative.

Setting of the scene: The setting of the scene provides the circumstances that lead up to the dream. Dodson (2009:140-141) identifies two formal features of the scene-setting. Firstly, the identity of the dreamer is given along with a description of his character. Matthew describes Joseph's pious character (δίκαιος ὢν καὶ µὴ θέλων αὐτὴν δειγµατίσαι).9 As a righteous person he is confronted with a serious moral dilemma. Joseph lived in a society where Jewish, Greek and Roman laws all demanded a man to divorce his wife if she were guilty of adultery. Jewish law demanded that a man immediately charge his wife on the discovery that she had not been a virgin (p. Ketub. 1.4 par. 4). Although Joseph and Mary at that stage were engaged and not married yet, it still applied that he would have to end the engagement. The second feature is a description of his mental state, ταῦτα δὲ αὐτοῦ ἐνθυµηθέντος (but after he had considered this). As Joseph is unaware that Mary's pregnancy is of divine intervention, he is on the verge of leaving her. Yet before Joseph could divorce her, God intervened.

The genitive absolute (ταῦτα δὲ αὐτοῦ ἐνθυµηθέντος) connects the dream with the narrative context (Davies & Allison 2004a:198; Dodson 2009:135). The angel appears as a well-timed divine intervention.

The appearance of the angel: The divine intervention is exemplified with the interjection ἰδοὺ (behold). This Greek interjection and its Semitic equivalent (henneh) are common to angelic appearances, theophanies and birth announcements (e.g. Gn 16:11; 17:19; Jdg 13:3). This interjection signals the importance of the intervention, of the angel and of his message (Davies & Allison 2004a:206).

Although Luke in his infancy narratives describes the angel of the Lord as the archangel Gabriel 'who stands in the presence of the Lord' (Lk 1:19), the angel in Matthew remains nameless. Matthew only states the divine origin of the angel as a messenger of God, being an angel of the Lord (ἄγγελος κυρίου).10

The angel appears to Joseph in a dream.11 Typical dream terminology (κατ' ὄναρ) is used. Of all the New Testament writers, Matthew especially emphasises revelations through dreams (e.g. Mt 2:12, 13, 19, 22; 27:19). In antiquity, dreams were considered as an authentic way to hear the words of God, especially when it is an angel of the Lord that acts as the messenger (Bendoraitis 2015:38; Davies & Allison 2004a:207).

The message of the angel: The angel gives Joseph two instructions: not be afraid to take Mary as his wife (Mt 1:20) and to name the child Jesus (Mt 1:21). Both instructions are followed by reasons: Mary has conceived a child through the Holy Spirit (Mt 1:20), and Jesus would save his people from their sins (Mt 1:21). These reasons describe the significance and greatness of the child.

The first instruction, µὴ φοβηθῇς (do not be afraid), is common to theophanies and angel appearances in the Old Testament and significantly so in promises of an offspring (cf. Gn 15:1; 26:4; 26:3). The angel continues by providing the reason for not being afraid, τὸ γὰρ ἐν αὐτῇ γεννηθὲν ἐκ Πνεύµατός ἐστιν Ἁγίου (what is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit) (Mt 1:20).

The message hereby relays several of the character traits of the child. The words imply that the child is holy. He is also unique as such means of conception were unprecedented. Although kings were often said to have miraculous births in antiquity, virginal conception has no exact parallels in Jewish12 or Graeco-Roman stories. Furthermore, these words imply the divinity of the child (Witherington III 2006:43).

The angel furthermore instructs Joseph to call the child Jesus (καὶ καλέσεις τὸ ὄνοµα αὐτοῦ Ἰησοῦν),13 and once again gives a reason for this (αὐτὸς γὰρ σώσει τὸν λαὸν αὐτοῦ ἀπὸ τῶν ἁµαρτιῶν αὐτῶν) (Mt 1:21).14 According to an halakhic midrash, Mekhlita to Exodus 13:2, those who received their names directly from God were regarded to be particularly important and righteous people (Davies & Allison 2004a:210). This Hebrew name and the way it is given therefore indicate the role the son would play as a particularly important and righteous person. He is sent to Israel, who has gone astray, to save them from their sins. This implies more than personal repentance. It invokes the Old Testament hopes of salvation of God's people. The angel does not explain how Jesus would save, but the Gospel ultimately answers this question in the narrative of Jesus' passion and resurrection that follows.

Joseph's obedient response: Once the angel has delivered his message, nothing more is said of him, yet his authority is apparent as Joseph obeys his heavenly direction15 to take Mary as his wife and to name the child (Mt 1:24). 16

Because Joseph alone received the revelation from the angel, outsiders would still suspect Mary to have gotten pregnant in a disgraceful manner. Mediterranean society viewed the weakness of a man who let his love for his wife outweigh what was regarded as his appropriate honour to repudiate her with contempt (as Diodorus of Sicily wrote in Bibliotheca historica, 32.10.9)17 (Keener 1999:91). This means that Joseph would remain an object of shame in a society dominated with a culture of honour and shame. Nevertheless, Joseph obeys the command of the angel, which would have cost him his reputation in society.

The narrative underlines Joseph and Mary's moral nobility (Keener 1999:88). This confirms the purity of Jesus' origin. Ancient biographies often began with the noble family background of the protagonist, for example the biographies of Themistocles18 and of Alcibiades.19 The hero's background was considered to define his character.

Joseph obeys the angel by naming the child. By naming the child, Joseph takes responsibility for the child and becomes his legal father. With his opening words, the angel addresses Joseph as 'υἱὸς Δαυείδ' (son of David) (Mt 1:20). Besides Jesus, only Joseph is given this title. With this adoption, Jesus also becomes a son of David (Keener 1999:86; Witherington III 2006:45). The child would only legitimately be recognised as Messiah if his Davidic lineage could be proved (Cabrido 2012:71; Levine 2006:431).

Fulfilment of a prophesy

After the angel has finished delivering his message to Joseph, the evangelist interprets the words of the angel with a quotation from the Jewish Scriptures.20 It provides commentary on the significance of the events taking place in relation to the dream report.21 With this fulfilment quotation the evangelist demonstrates that this has been part of God's divine plan from before Jesus was born (Bendoraitis 2015:50). In all of Matthew's fulfilment quotations, the phrase τὸ ῥηθὲν ὑπὸ Κυρίου (the word of the Lord) appears only twice, both cases with the appearance of the angel of the Lord in the birth and infancy narrative. Matthew quotes from Isaiah 7:14 LXX (Mt 1:22-23). The evangelist explains that the name has to do with Jesus' identity as Immanuel. He would be the living presence of God with his people. This idea is recapitulated at the end of the Gospel in Matthew 28:20 where the exalted Christ promises to be with his people until the end of age.

Instructing Joseph to escape to Egypt (Mt 2:13-15)

Although Matthew 1 deals primarily with the situation before Jesus' birth, Matthew 2 narrates events after his birth. Both chapters treat circumstances surrounding Jesus' birth. Matthew 2 represents a conventional 'cultural hypotext' regarding the threat and rescue of a royal child (Luz 1989:129).

The two subsequent dream reports repeat many of the features found in the first report. Much of what has been said there also applies to the next two cases.

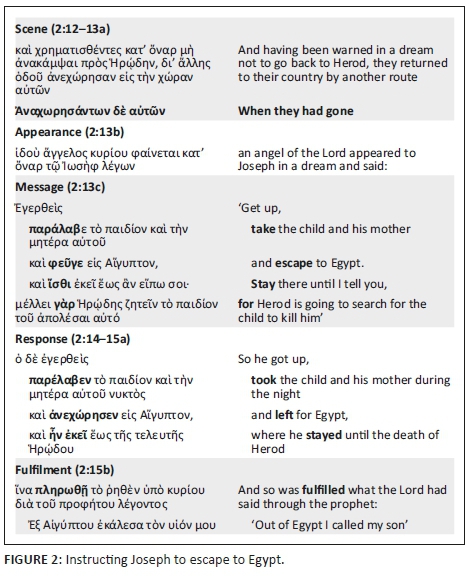

The second appearance or the angel of the Lord is narrated in Matthew 2:13-15 (see Figure 2).

Setting of the scene: The angel of the Lord again appears to Joseph at the point of a developing crisis. The narrator tells that the magi have been warned in a dream not to return to Herod because of his malicious plan to get rid of the baby.22 The life of the baby is in danger. Once again the genitive absolute, Ἀναχωρησάντων δὲ αὐτῶν (when they had gone), connects the dream with the narrative context.23

The appearance of the angel: The appearance of the angel follows directly after the magi leave. The description of this appearance of the angel is almost a repetition of the description of his previous appearance (Mt 1:20-21). Once again it opens with the interjection ἰδοὺ (behold) to signify the well-timed divine intervention, the awe for the angel and the content of his message.

The message of the angel: The angel instructs Joseph to take his family and to flee to Egypt, followed by the reason of this instruction - Herod is trying to find and kill the child. The message reveals that the child is both subject to God's protection and the wrath of Herod as it describes God's protection during events involving Herod's brutal massacre of little children. Ancient literature frequently describes divine children overcoming evil opposition (e.g. Apian R.H. 1.1.2). In a world of brutality and tragedies, this story speaks of a divinely protected fugitive who would ultimately triumph over evil forces (Keener 1999:107). Furthermore, this narrative recalls the protection of Moses as a baby.24 Jesus goes to Egypt as Israel went there under the first Joseph, and Herod, like Pharaoh, kills male children (cf. Ex 1:16-2:5; Ps-Philo 9:1).25 The message depicts Jesus as refugee. It foreshadows Jesus' rejection as an adult, the Son of Man, who would have no place to lay his head (Mt 8:20).

Joseph's obedient response: Similar to the response to the angel in the first dream appearance, Joseph immediately obeys the instruction of the angel. The divine timing of the appearance and Joseph's response are demonstrated in the subsequent verses as the narrator tells that Herod has instructed that children under the age of two should be found and killed (Mt 2:16-18).

Fulfilment of a prophesy: Using the same introductory phrase as in Matthew 1:22, the narrator again states that this was 'to fulfil what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophets' (Mt 2:15), connecting the consequences of the dream with the fulfilment of prophecy. This return is seen as recapitulating the return of Israel from Egypt, being called out of Israel as God's child (Floor 1969:35). Jesus' sojourn in Egypt fulfils the prophesy of Hosea 11:1, 'Out of Egypt I have called my son'.26 In Hosea 'son' refers to Israel and Matthew here applies it to Jesus.27 God called Israel his 'first born son' (Ex 4:22-23). With this fulfilment citation, Matthew presents Jesus as the embodiment of the true, obedient 'son of God' (Davies & Allison 2004a:263). The implication is also that God calls his son Jesus to identify with the sufferings of his people in exile (Keener 1999:112; Menken 2004:136). The evangelist teaches that in Jesus God's anticipated salvation of his people has begun. Jesus is depicted as the forerunner of the new exodus, the time of ultimate salvation.28

It is significant that Matthew uses the Masoretic text and not the Septuagint for this quotation. Although the Septuagint refers to 'child', which would be linked to Israel, the Masoretic text refers to 'son', which would be linked to a royal figure. It seems that Matthew deliberately uses the version that would define Jesus as a royal figure. He is the son of David and therefore the King of the Jews to free Israel, and not to be Israel (Witherington III 2006:69).

Instructing Joseph to return to Israel (Mt 2:19-23)

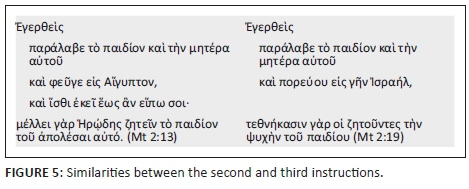

The third appearance of the angel of the Lord takes place in Egypt when he instructs Joseph to return to Israel (see Figure 3). The passage has the same structure as the previous one where Joseph was instructed to escape to Egypt (Mt 2:13-15) (see Figure 4). The angel once again appears in a dream, gives an instruction and Joseph gets up and does what he is commanded to do (see Figure 5). Matthew links these events to the fulfilment of scriptures.

Setting of the scene: Once again the genitive absolute, Τελευτήσαντος δὲ τοῦ Ἡρῴδου, connects the dream with the narrative context. Herod, the despot who wanted to kill Jesus, has died.

Appearance of the angel: Once the scene is set, the angel appears.

The wording of this appearance is very similar to the previous appearance. What has been said before about the significance of the appearance of the angel therefore again applies in this case. The only difference is that the location 'ἐν Αἰγύπτῳ' is added. This confirms that Joseph obediently stayed in Egypt until the angel visited him again with a new instruction.

The message of the angel: As with the appearance of the angel, the message of the angel also bears a strong resemblance to his previous instruction.

The words of the angel are highly ironic. Although the death of Herod is previously mentioned, '… he stayed until the death of Herod (ἕως τῆς τελευτῆς Ἡρῴδου)' (Mt 2:15) and 'after Herod died (Τελευτήσαντος δὲ τοῦ Ἡρῴδου)' (Mt 2:19), the angel once more mentions Herod's death. The irony is that Herod the king, whose primary aim throughout the narrative was to kill the child, is himself dead although the child targeted is well and alive. This sharp contrast is stated in the words of the angel and emphasised by the position of the verb at the beginning of the phrase: 'τεθνήκασιν γὰρ οἱ ζητοῦντες τὴν ψυχὴν τοῦ παιδίου' (for dead are those who were trying to take the child's life) (Mt 2:20). 'For the readers of the Gospel, there is no doubt about who has the power of life and death over Herod: it is God' (Patte 1987:36). Matthew clearly states that Herod was not the genuine king of Judea and he did not hold the actual power. Instead Jesus, as new born King of the Jews, held the power. True power belonged to the vulnerable child and not to the terrifying despot.

The angel's instruction to return to Israel bears a strong resemblance to the Lord's instruction to Moses in Midian to return to Egypt: 'go back to Egypt, for all the men who wanted to kill you are dead …' (Ex 4:19). Like Moses, Jesus outlives the persecution and he leads his people to salvation (Davies & Allison 2004a:271; Keener 1999:112). The preceding verse in the Septuagint notes that the king of Egypt has died, 'ἐτελεύτησεν ὁ βασιλεὺς Αἰγύπτου' (LXX Ex 4:18). As with Moses, the Lord once again offers assurance that the danger has passed.

Joseph's obedient response: Once again, the message of the angel is followed by Joseph's obedient response (Mt 2:21-23a), which has strong similarities with his response to flee to Egypt (Mt 2:14-15a). It also bears strong resemblance to Moses' return to Egypt: 'so Moses took his wife and sons, put them on a donkey and started back to Egypt' (Ex 4:20).

Fulfilment of a prophesy: Matthew once again verifies the instruction of the angel with a fulfilment quotation. In contrast to the previous two fulfilment quotations after the angel's appearance, the scriptural reference does not match any particular Old Testament text.29 It nevertheless signifies Jesus' identity and that God directed and protected Jesus and his family (Bendoraitis 2015:49).

Instructing the women at the empty tomb (Mt 28:2-10)

The angel of the Lord once again appears at the end of the Gospel at the empty tomb (Mt 28:2-8) (see Figure 6).30

The appearance of the angel

This is the first time since in the birth and childhood narratives (Mt 1:20-24 and 2:13-19) that the angel of the Lord (ἄγγελος Κυρίου) appears. Unlike in the birth and childhood narratives, the angel descends in body and not in a dream. Although the evangelist does not give any description of the angel in the previous three accounts, he does now. He expands the description of the 'young man' found in Mark.31 His appearance communicates a heavenly presence and power that awakes awe and fear. It was frightening for the guards and the women, as he came with a violent earthquake (σεισµὸς ἐγένετο µέγας), his appearance was like lightning (ὡς ἀστραπὴ) and his clothes were white as snow (ὡς χιών).32 The earthquake recalls the seismic activity with Jesus' death and can be associated with the rolling of the tomb stone. The appearance of the angel exhibits similarities with other biblical theophanies (Keener 1999:700). It resembles Jesus' glory on the Mount of transfiguration (Mt 17:2) (cf. Dn 7:9; 10:5-6). In 4 Ezra 10:25-27, the heavenly Zion has a countenance that flashes like lightning and at its voice, the earth trembles. In 3 Enoch 22:9, the face of the angel shines and earthquakes accompany him. The angel sitting on the stone in an elevated posture is in itself a statement of supernatural triumph. Single-handedly rolling away the stone would require supernatural strength.

The irony with the appearance of the angel is significant. After trembling (ἐσείσθησαν) at the angel's shaking of the earth (σεισµὸς),33 those who were supposed to guard the dead become like the dead (ὡς νεκροί)34 (Davies & Allison 2004b:666; Witherington III 2006:528). This reaction before a deity's holiness reflects biblical traditions (cf. Mt 17:6; Rv 1:17). As in the birth narratives, the appearance of the angel of the Lord demonstrates that God is in control of what is happening, this time with the addition of the eschatological significance of the resurrection.

The message of the angel

With the guards disabled and unconscious, the angel continues to deliver his message to the women. The angel announces the resurrection and gives a series of commands.

As with Joseph with his first appearance in the narrative, the angel again tells the women not to fear (Μὴ φοβεῖσθε). The angel continues to explain to the women why Jesus is no longer in the tomb. It is remarkable that the angel calls Jesus the crucified one (Ἰησοῦν τὸν ἐσταυρωµένον) even though he has risen (ἠγέρθη). The participle τὸν ἐσταυρωµένον is in the perfect tense, indicating an event that took place in the past, but has lasting effect (Witherington III 2006:528). Jesus is permanently the crucified one although at the same time being the risen one.35 The divine passive is used in ἠγέρθη, which indicates that the resurrection was an act of God (cf. Ac 3:15; 4:10; Rm 4:24; 8:11; 10:9; 1 Pt 2:21).

The women are instructed to come and see the place where Jesus was buried, and then to go and tell his disciples that he has been raised and is going ahead of them to Galilee.

Response

Although afraid, the women are filled with joy. As in the case with Joseph, they obey the angel and run to tell the disciples.

Conclusion

The angel of the Lord plays a significant role in Matthew's portrayal of Jesus. Although the evangelist does not explicitly explain who the angel of the Lord is, he draws upon existing Jewish traditions. He emphasises the divine origin of the angel as a messenger from God each time he identifies him as the angel of the Lord (ἄγγελος κυρίου). This authority is expressed as Joseph and the women obey his instructions each time, by his triumphal posture at the tomb and by the fearful reaction of the guards and women at the tomb.

Through the angel of the Lord, God is at work in Jesus' life, not only protecting him, but also signifying Jesus' identity. The messages of this angel underscore God's providence and Jesus' divine power and authority.

The appearance of the angel in the birth and infancy narratives corresponds with the function of such divine appearances in Graeco-Roman literature. Such dreams were associated with divination. Dreams were regarded as the way the divine enters human affairs to carry out divine will. It signifies the importance and greatness of Jesus. In Matthew 2, the appearance of the angel resembles the cultural hypotext of the threat and rescue of a royal child. He is divinely protected from the threat of Herod.

This angel bears witness to the uniqueness of the child, on the basis of his miraculous conception. The genesis of the child is no less than an act of God. He attests to the divinity of the child. His family background speaks of moral nobility. The name he is given indicates the role he has to play in saving his people from their sins. As son of David, he is a royal figure. He expresses God's presence.

The angel links the child with God's divine plan. This is enhanced by the double dream report of warnings to the magi and to Joseph in Matthew 2 to create a divinely led beneficial circumstance for the child.

He becomes a fugitive. He identifies himself with the suffering of the exile of his people. However, he is divinely protected. He would ultimately triumph over evil forces. As newborn King of the Jews, he holds the power and not Herod, the terrifying despot.

In conjunction with the messages of the angel, the fulfilment quotations in the birth and childhood narratives signify Jesus' identity. What happens to Jesus forms part of God's divine plan from before Jesus was born. He would become the crucified one, although at the same time the risen one. His crucifixion would have a lasting effect.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

The author declares that he is the sole contributor for this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for carrying out research.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Bauer, D.R., 1992, 'The major characters of Matthew's story: Their function and significance', Interpretation 46(4), 357-367. https://doi.org/10.1177/002096439204600404 [ Links ]

Bendoraitis, K.A., 2015, Behold, the angels came and served him, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Burridge, R.A., 1992, What are the gospels? A comparison with Greco-Roman biography, University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Brown, R.E., 1993, The birth of the Messiah: A commentary on the infancy narratives in the gospels of Matthew and Luke, Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

Cabrido, J.A., 2012, The portrayal of Jesus in the gospel of Matthew, Mellen, Lewiston, ME. [ Links ]

Culpepper, R.A., 1984, 'Story and history in the Gospels', Review and Expositor 81(3), 467-478. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463738408100311 [ Links ]

Davidson, M.J., 1992, Angels and Qumran: A comparative study of 1 Enoch 1-36, 72-108 and sectarian writings from Qumran, JSOT Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004a, The international critical commentary on the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament, Matthew 1-7, T&T Clark, London & New York. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004b, The international critical commentary on the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament, Matthew 19-28, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Dodson, D., 2002, 'Dreams, the ancient novel, and the gospel of Matthew: An intertextual study', Perspectives in Religious Studies 29(1), 39-52. [ Links ]

Dodson, D., 2009, Reading dreams: An audience-critical approach to the dreams in the gospel of Matthew, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Floor, L., 1969, De nieuwe exodus: Representatie en inkorporatie in het Nieuwe Testament, PU vir CHO, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Gnuse, R., 1990, 'Dream genre in the Matthean infancy narratives', Novum Testamentum 32(2), 97-120. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853690X00016 [ Links ]

Hays, M.H., 2013, 'Towards a faithful criticism', in C.M. Hays & C.B. Ansbury (eds.), Evangelical faith and the challenge of historical criticism, pp. 1-23, Baker, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Keener, G.S., 1999, A commentary on the gospel of Matthew, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI & Cambridge. [ Links ]

Levine, Y., 2006, 'Jesus "son of God" and "son of David": The "adoption" of Jesus into the Davidic line', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 28(4), 415-442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X06065693 [ Links ]

Luz, U., 1989, Matthew 1-7: A commentary, Augsburg Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Menken, M.J.J., 2004, Matthew's Bible. The Old Testament text of the Evangelist, University Press, Leuven. [ Links ]

Patte, D., 1987, The gospel according to Matthew: A structural commentary on Matthew's faith, Fortress, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Powell, M.A., 1990, What is narrative criticism?, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Powell, M.A., 2009, 'Literary approaches and the gospel of Matthew', in M.A. Powel (ed.), Methods for Matthew, pp. 44-82, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511627118.005 [ Links ]

Sullivan, K.P., 2004, Wrestling with angels: A study of the relationship between angels and humans in ancient Jewish literature and the New Testament, Brill, Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004331099_014 [ Links ]

Viljoen, F.P., 2018, 'Reading Matthew as a historical narrative', In die Skriflig 52(1), a2390. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v52i1.2390 [ Links ]

Weren, W.J.C., 2014, Studies in Matthew's gospel; literary design, intertextuality, and social setting, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Witherington, III, B., 2006, Matthew, Smyth & Helwys, Macon, GA. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Francois Viljoen

viljoen.francois@nwu.ac.za

Received: 29 Aug. 2019

Accepted: 06 Feb. 2020

Published: 19 Mar. 2020

1 . The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls confirms the significance of angels in the time of the New Testament (cf. Davidson 1992).

2 . Reading the gospels as narratives should not invalidate the historical and theological questions about the text (Hays 2013:17; Powell 1990:98, 2009:44). The gospels are related to the world of Jesus and the social world of the evangelist in various ways (Culpepper 1984:472; Viljoen 2018:1).

3 . In Jewish and early Christian literature there is much speculation about the relationship between Jesus and angels. In some circles, the angel of the Lord is identified as the pre-incarnate Jesus. However, such identification is a simplification (Bendoraitis 2015:12).

4 . Jesus is the principal character in the narrative of the Gospel. There are only a few 'scenes' where he is not personally present. However, all scenes are related to Jesus. His teachings and actions are in the spotlight, and the actions of other characters all relate to him (Bauer 1992:357; Powell 1990:54; Weren 2014:12).

5 . Typical of this genre, the Gospel focusses its attention on Jesus of Nazareth. Like the ancient βίοι (biographies), the Gospel not only instructs and expresses adoration of Jesus, but also sets models for the audience to follow (Burridge 1992:214). Matthew does not only include praise and blame with respect to individuals, but also states that they should pursue fairness and truth.

6 . Matthew's Gospel contains six references to dreams: five in the birth and infancy narratives (Mt 1:20; 2:12, 13, 19, 22) and one in the passion narrative (Mt 27:19). Only three of these are proper dream reports, Matthew 1:18b-24; 2:13-15; and 2:19-21. These dream reports formally correspond to those in the Graeco-Roman world. They usually contain (1) a scene-setting, (2) dream-vision terminology, (3) a proper dream vision and (4) reaction and response (Dodson 2002:46; Gnuse 1990:114). Matthew employs this literary convention of his day.

7 . Davies and Allison (2004a:196) suggest a slightly different outline of this pattern.

8 . This intervention of the angel is similar to life-changing interventions in the lives of the patriarchs (e.g. Gn 22:9).

9 . Matthew uses the word δίκαιος around 17 times, always in a positive sense. Jesus is the ultimate example of righteousness. Righteousness also forms an identity marker of Jesus' followers.

10 . The ancient Graeco-Roman writings often give the relationship between the dreamer and the dream figure and a description of the dream figure (Dodson 2009:142). In Matthew, these elements are toned down, probably to put the emphasis on the message.

11 . In Matthew's narrative, the angel of the Lord only appears in dreams until the appearance in Matthew 28:2.

12 . It is unlikely that the idea of virginal conception was generated by the reading of Isaiah 7:14 as cited in Matthew 1:23. The text in Isaiah could simply mean that a young woman who previously had no sexual intercourse would conceive in a normal way to bear a child. It is rather Jesus' miraculous birth that led to the reading of Isaiah 7:14 in a new light (Menken 2004:124; Weren 2014:126; Witherington III 2006:43).

13 . It is significant that although Jesus' name occurs around 150 times in Matthew, none of the human characters addresses him as such in this Gospel. The probable reason is that the Gospel avoids to portray Jesus as a mere mortal human being, but rather as 'God with us' (Witherington III 2006:48).

14 . This interpretative wordplay of 'Jesus' and 'He will save his people of their sins' and 'Immanuel', which means 'God with us', is typical of ancient dream reports (Dodson 2009:153). This contributes to the significance of the unborn child.

15 . Such obedience is a typical feature of ancient dream reports and would be expected by the ancient audience (Dodson 2009:145).

16 . Joseph's obedience foreshadows Jesus' obedience to God throughout his earthy life and shows what Jesus requires of his followers (e.g. Mt 7:21; 12:50).

17 . Diodorus of Sicily was an ancient Greek historian known for writing the 'Bibliotheca historica' between 60 and 30 BC.

18 . The Decree of Themistocles describes the evacuation of Attica by the Peloponnesian army in 480 BC, which purports to be issued by the Athenian assembly under the guidance of Themistocles.

19 . Alcibiades (c. 450-404 BC) was an important Athenian politician and military commander.

20 . It is unclear whether the fulfilment quotation forms part of the angel's message, or whether it is an interpretation by the narrator. Davies and Allison (2004a:211) opt for the formula as an editorial remark. In a similar vein, Brown (1993:144) remarks: 'occurring where it does, the citation in 1:22-23 is intrusive in the flow of the narrative … (verses) 24-25 is the real continuation of the angelic appearance in 20-21 … 22-23 is obviously an insertion'. However, such asides by the narrator are not uncommon in Graeco-Roman ancient literature (cf. Dodson 2009:143). Yet, the quotation does not conclude the dream report but is included in it, which suggests that it could just as well have formed part of the angel's words.

21 . In ancient Greek literature, a number of dream reports included quotations from Homer. In Jewish tradition of literary dreams it is paralleled by quotations from Jewish Scriptures (cf. Dodson 2009:154).

22 . Although magi were known for their interpretation of the dreams of others, they here themselves receive the divine message. Later in the narrative, Pilate's wife also has a dream that repeats motifs that characterise Jesus. He is innocent, in contrast to the Jewish leaders in both cases.

23 . The dreams of the magi and that of Joseph represent a double dream report. Both are intended to avoid Herod's plot and to safeguard the child. They function together to produce beneficial circumstances for Jesus (Dodson 2009:162).

24 . The narrative of the birth of Moses also represents the conventional 'cultural hypotext' regarding the threat and rescue of a royal child.

25 . Gnuse (1990:107) argues that dreams in Matthew's infancy narratives share many similarities with 'Elohist' dreams found in Genesis (20:3-8; 28:12-16; 31:10-13; 31:24; and 46:2-4) and could be considered as imitations of those dreams. However, although the dream reports in Matthew are almost repetitive in structure, the dream reports in Genesis are diverse and more elaborate.

26 . The placement of the fulfilment quotation is unusual and strange as it looks forward to the event of the family's return from Egypt, which is still to be narrated. However, this placement makes it possible to maintain the similar structure of the narratives on the angelic appearances.

27 . Matthew here refers to Jesus as the 'son' for the first time, a designation that would be repeated at his baptism (Mt 3:17) and at the temptation by the devil (Mt 4:3-7).

28 . Jesus embodies Israel's purpose and mission (Keener 1999:109). Other than Israel, when Jesus is tempted in the wilderness, he does not wander around and grumble for 40 years. He passes the wilderness in only 40 days although resisting the temptations of the devil. Rather than sinning himself, he saves his people from their sins.

29 . Menken (2004:177) argues that Matthew might have referred to Judges 13:5, 7 which may indicate a parallel between Samson and Jesus. Addressed as Ναζωραῖος, Jesus could have been known as a person from Nazareth.

30 . The four gospels differ in detail in their resurrection narratives (Mk 16:1-9; Lk. 24:1-12; and Jn 20:1-18). However, similar elements are present: women, an empty tomb, a heavenly messenger and fear. In all four gospels, the women are the first witnesses.

31 . In the Gospel of Mark, the women found a young man dressed in a white robe (Mk 16:5). Although Mark does not call the man an angel, the language and context suggest the he was an angel. His white garment is indicative of heavenly origin. It was not unusual to speak of an angel as a young man (cf. Ac 1:10; 10:30; 2 Macc 3:26, 33; Gos. Pt 9:36) (Bendoraitis 2015:191; Davies & Allison 2004b:665).

32 . Following the last reference to the warrior angels in Matthew 26:53, the image is striking.

33 . Soldiers, who must have been used to tumult, are terrified and fall to the ground, although the women remain standing and are comforted by the angel.

34 . The guards at the cross (Mt 27:54) who experience the earthquake and miracles also fear, but come to faith. However, the guards at the tomb do not come to faith.

35 . This message recalls the confession in 1 Corinthians 15:3-5, Christ died and was buried and was raised.